INTRODUCTION

The use of technologies in the field of health, through telemedicine or long-distance support media, has increased dramatically in recent years with the help of remote monitoring of patients, mobile health applications, teleconferences, etc. These resources become significant in response to disasters or conditions that deteriorate health and life1 . While telemedicine has historically been considered to facilitate the provision of services in rural or geographically remote areas, underserved populations, economically or medically vulnerable populations; in recent years, it has been introduced as another resource for health care2. Among its benefits has been described: decreased deaths and deterioration of health, reduction of hospital admissions, decrease unnecessary transportation to medical centers and increased effectiveness of medical personnel 3) (4.

In 2016, it has been provided for the first time for the incorporation of telemedicine into the national health system and the general guidelines for its implementation and development were established as a health delivery strategy 5 ; subsequently, in 2019, the provisions were adopted in order to expand its coverage through the use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) 6 .

Following the notification of a cluster of cases in Wuhan City (Hubei, China), the COVID-19 outbreak was declared a pandemic on March 11th, 2020 7. In consequence, on March 15th, 2020, Peru declared restricted the right to free transit during the state of national emergency, and was allowed emergency-only access to face-to-face medical care. As a result, many patients were unable to access a medical consultation or appointments scheduled in person 8.

Faced with this situation and in response to the need for the population to access health services, on March 2020, the Ministry of Health (MINSA) gave the ministerial resolution No.146-2020 and in May 2020 teleorientation and telemonitoring was implemented and developed9) (10 . In these documents, "teleorientation" means the set of actions developed by a health professional through the use of ICT to provide the health user with counseling and advice for the purposes of promoting, preventing and recovering health; "teleconsultation" means the remote consultation with the use of ICT that, unlike "teleorientation", provides a prescription for medicines and other provisions determined by the MINSA; and finally, "telemonitoring" is the transmission of patient information for remote monitoring.

From March to May 2020, various ophthalmology services began their attention through teleorientations, both in institutions belonging to MINSA and EsSalud. Also from April through the web application "Teleatiendo"11, for example, in the MINSA the Arzobispo Loayza National Hospital and the National Institute of Ophthalmology 12) (13 , and in EsSalud, the Rebagliati Network and the Naylamp Hospital in Lambayeque14 . Then, in May 2020, teleorientation care was provided in the Ophthalmology service of Cayetano Heredia Hospital (CHH), through video called synchronous patient to physician(15), although the use of telehealth and teleconsultation for communication from doctor to doctor has been made since 2018 16.

Prior to the current pandemic, 74% of patients did not know they could take advantage of the telemedicine option in their doctors' consultations. However, this scenario has changed with social distancing rules and some leading telehealth platforms have reported an increase between 257% and 700% in the number of virtual patient visits, which correlates with the geographical impact of COVID-19 17.

This pandemic highlights the need to consider telemedicine as an alternative to patient care; because it allows a patient-centered evaluation, this in turn promotes self-isolation and therefore protects doctors and the community. It also seeks serious criteria and risk factors that could justify immediate face-to-face care, resolves administrative needs (certificates, prescription renewal), provides basic therapeutic recommendations, and monitors clinical evolution of patients18) (19 . Even in the field of ophthalmology, its permanent post-pandemic role is already being considered 20.

The objective of this work is to identify the most common presumptive diagnoses of patients treated by teleorientation in the ophthalmology service of CHH from May to August 2020. As specific objectives we have: to describe the sociodemographic characteristics of patients cared for by teleorientation; to identify the percentage of patients who required face-to-face care after being evaluated by teleorientation; and to find if the older adults required greater family attendance than the non-older adults for the use of teleorientation.

METHODS

This was a descriptive, observational, retrospective study of a database that was collected by the Ophthalmology Service in CHH located in the district of San Martín de Porres, Lima, Peru.

All patients who entered the teleorientation from May to August 2020 were included in the study. A database collected by the Ophthalmology Service in CHH was used. All patients whose data were found to be incomplete were excluded.

MEASURES

Sociodemographic feature variables:

1. Sex: "male" or "female". It is defined as the patient's birth sex.

2. Age: patient age. It is defined as the patient's age in years

3. Age group: "older adult" or "non-older adult". The definition of older adult was used as an age of equal or over to 60 years old and non-older adult as patients under 60 years old, MINSA 2010(21).

4. Origin: "Metropolitan Lima" or "non-Metropolitan Lima". It is defined as the place where the patient resides and for geographical locations were considered the definitions of the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (INEI) (22).

5. Family attendance: "yes" or "no". It is defined as the fact that the patient has or has not required the attendance or help of a family member or caregiver in order to access the teleorientation from home.

Clinical characteristic variables:

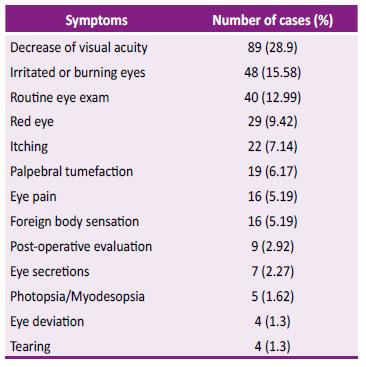

1. Symptom: "decrease of visual acuity", "Irritated or burning eyes", "routine eye exam", "red eye", "palpebral tumefaction", "foreign body sensation", "eye pain", "eye secretions", "photopsia /myodesopsia", "tearing", "eye deviation", and "post-operative evaluation". It is defined as the main symptom referred to by the patient at the time of teleorientation.

2. Diagnosis: "dry eye syndrome", "cataract", "glaucoma", "chalazion", "viral/bacterial conjunctivitis", "refractive errors", "post-operated", "acute dacryocystitis", "agerelated macular degeneration", "blepharitis", "vitreous detachment", "allergic conjunctivitis", "strabismus", "diabetic retinopathy", "subconjunctival hemorrhage", "pterygium", "uveitis", "keratoconus", "optic neuropathy", "episcleritis", "papilloma", "eye trauma". It is defined as the presumptive diagnosis made by an ophthalmologist at the time of teleorientation.

PROCEDURES AND TECHNIQUES

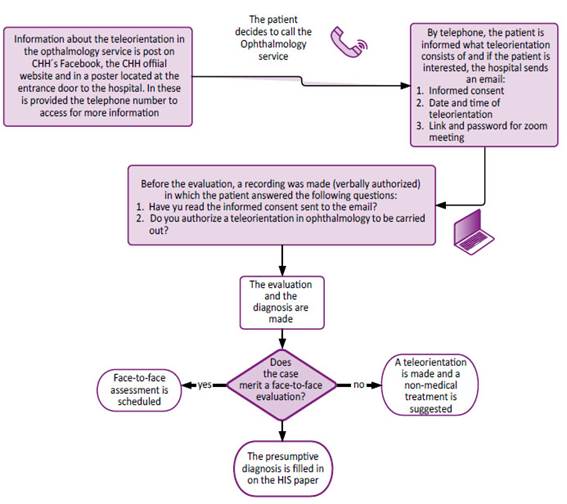

The data collection of was done as follows: Patients who were wishing to apply for the remote service called the CHH´s telephone number and asked for the annex to the ophthalmology service. Then, it was explained what the teleorientation consisted of a conversation via a videocamera with Zoom meeting app using a smartphone or a computer/laptop for it. If the patient wished to access a teleorientation, an appointment was scheduled according to patient and ophthalmologist availability. The registration was then carried out in a database using Microsoft Excel and an email was sent to the patient with the scheduled date and the time for the teleorientation with the link to join the Zoom Meeting (Figure 1).

Three ophthalmologists (One general ophthalmologist and two retina specialists) were attending through the program called Zoom Meeting installed on a computer with broadband connection. Once the patient enters the previously sent link, the teleorientation is performed by evaluating the patient through the help of a videocamera. Each ophthalmologist had 30 minutes per patient and had a maximum of 13 patients per day. They determined the presumptive diagnosis and assessed the patient's symptoms and decided, by their medical criterion, whether or not the case merited a face-to-face evaluation and treatment. If the need for a face-to-face appointment was not identified, the ophthalmologist would guide the patient suggesting a therapeutic behavior and the possibility of access to another teleorientation if the case warranted it. On the contrary, if the need for an evaluation as an eye fundus and/or face-toface treatment as eyedrops for glaucoma was considered, an appointment was scheduled at the CHH. Finally, the presumptive diagnosis of the Health Information System (HIS) format was completed filling it with CIE-10 diagnosis (Figure 1).

Before the teleorientation, patient basic information was entered into a data matrix of the Microsoft Excel 2019 program to organize the virtual appointments. After that, was entered the conclusions of the evaluations as the presumptive diagnosis and the need of a face-to-face examination. This database was used to create this investigation and were included 389 patients. It should be noted that this database collected information only from remote management and did not record any more data outside of it. The ophthalmology service of the CHH did not have access to the physical clinic history in order to prevent a possible way to spread the coronavirus as a health care protocol. If the patient remembered the name of their personal ophthalmologist, they could have a virtual appointment with them.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The numerical and percentage distribution of qualitative variables was determined. The Shapiro Wilks test was used to determine if the quantitative variables had a normal distribution. If it had a normal distribution, it was presented with a mean and a standard deviation. If it did not have a normal distribution, I was presented with median and quartiles 25 and 75. For the third specific objective sand used the Chi2 test and Fisher's exact test to evaluate the correlation between two categorical variables (age group versus family attendance). Statistical analysis was done using the STATA ST 16 program.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Cayetano Heredia Peruvian University and the School of Medicine, who authorized the analysis of the database.

RESULTS

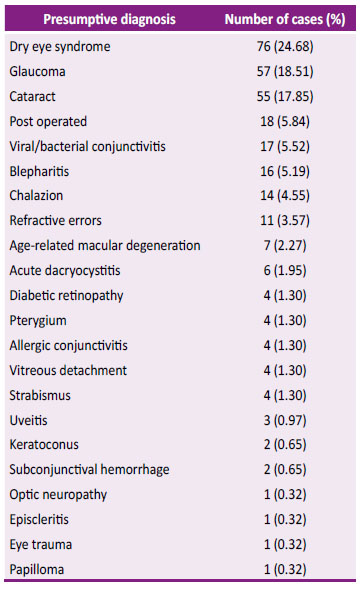

389 patients entered and 78 patients were excluded for incomplete data and 3 for data filling errors, so 308 patients were left for analysis. In them the most common presumptive diagnoses were dry eye syndrome, followed by cataract and glaucoma, as shown in Table 1. As for the symptoms these are presented in Table 2.

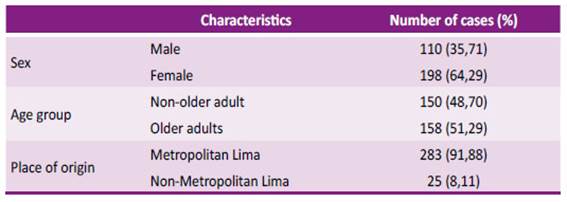

The median age was 55.73 years old (min. 1, max. 92, Q1-46, Q3-69) and 51.29% were older adults. The majority of patients were women (64.29%) and almost all resided in Metropolitan Lima (91.88%) as set out in Table 3.

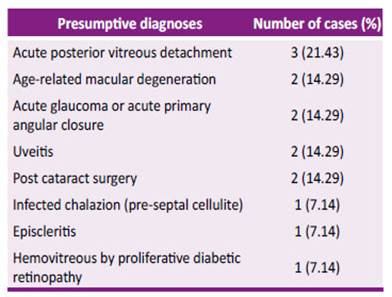

Of the 308 patients, 14 (4.55%) were cited for face-to-face evaluation and treatment after going through teleorientation, while in 294 (95.45%) teleorientation was sufficient for the management of the pathology at the time of consultation. The presumptive diagnoses of patients cited in the office were six of posterior segment and eight of anterior segment, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4 Presumptive diagnoses of patients who required faceto-face evaluation after teleorientation. (N = 14)

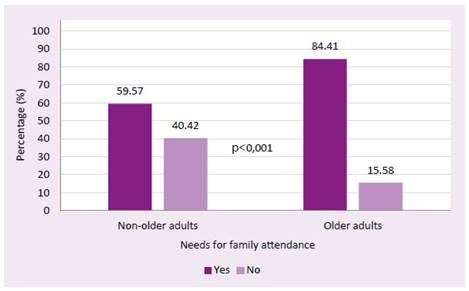

In addition, the third specific objective considered the variable ''family attendance'', with 171 patients, and a bivariate analysis found a statistically significant difference between the proportion of patients per age group ("older adults" and "non-older adults") to family care, which is seeing Figure 2.

DISCUSSION

This study analyses a remote sensing database whose start of collection took place in an absolute period of immobilization, when displacement was only possible in medical emergencies; but in the course of the "first wave" of the COVID-19 pandemic in Peru, these measures became less restrictive(23). Until the time of this publication many National Hospitals from different regions at the national level of networks of Lima, Piura, Pasco, Cajamarca and Arequipa and other regions through the web application "Teleatiendo" were added to the ophthalmological care by teleorientation, because due to the national state of emergency the ophthalmology services attend in person only emergencies and medical emergencies(24). It should be noted that the ophthalmology service of the CHH was never closed during the pandemic and eye emergencies were always attended to.

During the first wave of the pandemic, different studies on telemedicine in ophthalmology have been reported which vary in the method applied. For example, in our study, dry eye syndrome was the main diagnosis followed by cataract and glaucoma. Similarly, Mansoor et al. 17 , describes teleconsultation care at Al-Shifa Trust Ophthalmological Hospital, Rawalpindi, Pakistan. The study consisted of the evaluation of the usefulness of teleconsultation in ophthalmology during the emergency closure in March 2020 and were evaluated 1431 patients by audio and video with broadband telecommunications services. Their most common diagnoses were red eye (16,7%), Glaucoma (15,23%) and cataract (14,46%).

In Latin America, Arntz Et al.19 , conducted a descriptive study in the Ophthalmology service of the Telemedicine Service of the Health Network University Canolica-Christus of Chile. They had a population of 291 people, through the Zoom platform for 10 weeks, during the confinement period from March to June 2020. Their results describe the diagnoses as "Categories of reasons for consultation" where the most frequently nominated was "inflammatory eye surface conditions" (43,3%) which include dry eye, conjunctivitis, toxicity and allergy. In our study, the group of these pathologies also results in an important part of the population if we group patients with diagnoses of dry eye syndrome, bacterial/viral conjunctivitis and allergic conjunctivitis (31,5%).

Given the important frequency of diagnosis of glaucoma during telemedicine care in the pandemic, it has been proposed to treat this pathology through programs such as "teleglaucoma" which allows the management and monitoring of this disease in the long term, reduces the movement of patients and allows the updating of prescriptions25) (26 . For example, in the UK, those described as "Virtual Glaucoma Clinics" use teleglaucoma for long-term monitoring and treatment. In these clinics the "stable" patients are followed through a virtual review of glaucoma tests with a face-to-face evaluation only when it was necessary 27 .

The post-operated condition was a frequent diagnosis in our study. Also, in Kang Et al´s study, they collected a prospective data on 66 patients treated in 4 weeks through video consultations, replacing outpatient appointments canceled by the pandemic. They found that video evaluations allow the patient who has just had an eye surgery to have peace of mind about the postoperative outcome, prevent disease deterioration and management of medication 28 .

For eye emergency care, eye trauma was only present in 1 patient (0.32%). This low number was because probably in no level of healthcare center the emergency care was discontinued in person. About the frequency of such diagnosis there are several research, for example: Pellegrini et al. performed a retrospective study in Italy, where the insulation measures were rigid, and during a decrease of 68.4% of the common number of cases of eye trauma 29. In USA, during a period in which quarantine measures were not so restrictive, Berkenstock et al .( 30, report increase in eye injuries. However, in the same country, Wu Et al.31 , also did another study during an isolation period and found that the amount of severe eye trauma during quarantine remained stable, stating that patients should continue their prevention only with adequate protection.

In our population the number of older adults was 51,29%. Burdon et al.32 500 patients were studied in Paris, France, in a prospective cohort during the state of emergency between 20 March and 10 April 2020. In this study, he describes the population that accessed eye-in-room teleconsultations remotely and analyses the effectiveness of teleconsultation as a means of indicating a face-to-face consultation in eye emergencies. In its town, Bourdon et al. describes a median of 40,7 years old, it is less than the median of our data, with a clear decrease in patients over 60 years of age, a situation they attribute to the use of the internet as a means, which would cause their population to be younger to be able to handle teleconsultation as a resource. However, in our study the proportion of patients who needed family attendance was higher in the older adult population, so even though the teleconsultation care platform requires internet use and "Zoom Meeting" program became possible.

In our study the number of patients derived for face-to-face care after the teleorientation evaluation, because the case merited to complete a medical evaluation and for a treatment, was 14, In this group of patients some presumptive diagnoses were acute posterior vitreous detachment, macular degeneration, hemovitreous, pre-septal cellulite and episcleritis. Arntz Et al.19) reports similar pathologies in cases arising from a face-toface appointment after going through teleconsultation and were 7.5% (N = 22),for the following presumptive diagnoses: paraseptal cellulite (N = 6), suspected scleritis/keratitis (N = 5), eye trauma (N = 4), suspected strabismus (N = 4) and retinal vitreous symptoms 3 .

This study is not exempt from limitations. The advertisement of the service was very limited as its implementation was announced on the CHH website, Facebook page and physically only of a panel in the CHH entry. Therefore, it was probably only requested by those who visited such pages online or physically went to the hospital; very unlikely situation by the mobilization restricted from May to August 2020. Another necessary resource was internet access and the holding of a smartphone or a computer suitable to be able to access the Zoom Meeting application which, despite being free, is not necessarily accessible to all patients. In addition, the use of an electronic mail was another requirement to be able to access teleorientation, a factor that would also influence as a limitation of access, for as Malaga Et al. reported, in a study aimed at determining the use and perceptions of CHH patients´ ICTs and reported that patients had never used a computer (78.2%), or the internet (84%), or e-mail (84%) 33 . The image quality through the camcorder depended on the patient's internet speed. In order to improve the eye examination, patients were asked to use the front camera and be close to a light source to watch better the details. Another limitation is that through the camcorder the diagnoses could be raised only presumptively, with the possibility of sub-diagnosing or having possible misdiagnoses; since the examination cannot be performed with a slit lamp, tonometry and eye fundus. However, doctors' perception of ICT is positive, as described by Curioso et al. who through surveys assessed access, use and perceptions towards ICTs in CHH physicians 34 .

The main presumptive diagnosis was dry eye syndrome (24.68%). The number of patients cited in a post-teleorientation office was 4.55%. The number of older adults was 51.29% and of them 84.4% required family attendance.

In view of all of the above, our recommendations are: to improve the teleorientation service in the post-pandemic stage, improving protocols in such a way as to include virtual monitoring and monitoring of patients and to implement a system of immediate attention to possible emergencies detected.