1. Introduction

A safe environment is an essential requirement for ensuring the right to life. Awareness of the strong link between the environment and the right to life has led to the recognition of the right to a safe environment as a basic human right, and environmental legal relationships as a separate field of regulation. This defined the state’s obligation to preserve the natural environment and ensure a safe environment for citizens. The realization that the existence of humanity is directly linked to a safe and healthy environment should serve as an incentive to actively take measures to protect and develop nature (Fedele et al., 2021). The world’s leading democratic governments first responded to environmental changes associated to the rapidly growing industrialization half a century ago, by creating specialized governmental agencies and introducing environmental regulations.

The next step was the coordination to define actions aimed at protecting the environment at the international level setting forth relevant policies (Hausknost & Hammond, 2019). Nevertheless, these measures have proven to be both insufficient and too slow. Environmental problems continue to grow, becoming planetary in nature and threatening the very existence of humanity, which has chosen a self-destructive path, effectively destroying its habitat (Burns, 2023). Man-made climate change has become a reality, and there are already warnings of the onset of the sixth mass extinction (Sarliève, 2021). Human activities with an impact on the environment are seen in this context as a special kind of violence - environmental violence (Marcantonio & Fuentes, 2023). The understanding of this catastrophic situation has sparked a discussion about the need to consider ecocide as a crime that poses a global threat, affecting not only nature but also destroying the economy and, consequently, leading to severe social upheaval (Babakhani, 2023). Today, there is no universally recognized legal definition of ecocide, while the term itself means a combination of two components in Greek: the prefix “eco” meaning environment and the suffix “cide” meaning murder (Sarliève, 2021). The term ecocide was first coined by Arthur W. Galston in 1970 when discussing the devastating environmental consequences of the Vietnam War (Gardashuk, 2022).

Today, ecocide is also seen as the most serious environmental crime and a crime against sustainable development, considering that we need to take into account the interests of future generations of people when using natural resources and the attitude of current generations to the environment (Mehra et al., 2019). The specificity of the crime of ecocide lies primarily in its complex nature: it includes aspects of environmental crimes, human rights violations, resource consumption, etc. (Matwijkiw & Matwijkiw, 2023). Thus, its criminalization requires a multidisciplinary approach. In addition, ecocide has global implications, and therefore the adoption of separate laws on ecocide or its recognition as a crime at the national level does not allow for an effective solution to counter it. Therefore, international legal recognition of ecocide is urgent, as well as the incorporation of procedural tools to prosecute this crime. At the same time, ecocide has been discussed in various governmental and academic forums for half a century, gradually moving from the political to the legal arena and focusing on issues of both substantive and procedural law, as well as on the problem of compensation for victims of ecocide (Chiarini, 2022), but there is still no adequate response from the international community.

2. Literature review

The problem of ecocide is complex and includes both legal and environmental issues. In legal studies, ecocide is considered within the context of genocide, in particular related to the policy of colonialism, as an international environmental crime, and within the context of human rights. A separate branch of legal research studies the criminal liability for environmental offenses in the field of environmental protection.

Damage to the environment cannot but affect people's lives, sometimes leading to catastrophic consequences and threatening the very existence of certain communities and indigenous peoples. That is why ecocide is often associated with genocide. Thus, considering ecocide within the framework of genocide, as defined by the Rome Statute, Moribe, Pereira and França consider it is a method of the latter that threatens the existence of a particular culture, people or social group by destroying the ecology of their region. Ecocide shall thus be considered a crime against humanity (Moribe et al., 2023).

Eichler considers ecocide as a form of genocide, which consists in the destruction of non-human-made objects with a devastating impact on the life of a particular people, and refers to its two main aspects, the first of which is the need to expand the concept of genocide without changing its legal essence, and the second is the need to take into account the value of other living beings’ lives. Therefore, ecocide should be considered as an independent type of crime (Eichler, 2020). The connection between ecocide and genocide may be of a different nature. For example, ecocide could be not only a form of genocide, but also a driver of the latter, when it results in a shortage of natural resources (Galligan, 2021; Yaroshenko et al., 2024).

Crook, Short, and South see the origins of ecocide in colonialism and link it to the protection of the rights of indigenous peoples, while considering the violation of their rights and the harm caused to other living beings and organisms as parallel processes, emphasizing the need to address the problem of ecocide at the international level (Crook et al., 2018).

Ecocide poses a danger not only in specifically determined areas, but it also threatens the entire world. Therefore, it can be considered from two perspectives: human rights violations and environmental. Scholars who focus on the first group draw attention to the fact that current problems in the field of human rights and freedoms are largely related to the slow response of international and domestic law to changes in society (Haltsova et al., 2021). The response to environmental crimes is also very slow, and even the hostilities with the consequent significant aggravation of environmental problems have not changed this situation. The second group includes studies that consider ecocide from an environmental perspective, in relation to climate change, environmental degradation, among others (Chandel et al., 2023).

The war in Ukraine has raised the problem of military ecocide to a new level, which requires a comprehensive approach when studying environmental and legal issues in the context of war (Pavlova et al., 2023). Thus, Anisimova et al. (2023a, 2023b) point out that the events in Ukraine have demonstrated, among other things, a strong interconnection between environmental and social issues, with the former having a direct impact on the latter. On a global scale, Russia’s environmental crimes in Ukraine have significant negative consequences on previous efforts undertaken by the international community to address climate change (EUAM Ukraine, 2023).

3. Methods

The research comprised a number of tasks, distributed among the different stages of the study. The first task was finding out the peculiarities of ecocide regulations under Ukraine domestic law, and under the domestic law of other countries (e.g.: The Republic of Moldova, the Republic of Armenia, France), using the methods of analysis, synthesis and comparative legal analysis. For this part of the study, we used the following laws: the Criminal Code of Ukraine (Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, 2001), the Criminal Code of the Republic of Moldova (Parliament of the Republic of Moldova, 2002), the Criminal Code of the Republic of Armenia (2003), the Penal Code of Vietnam (Ministry of Justice of Vietnam, 1999), and the French Law No. 2021-1104 on combating climate change and strengthening resilience to its effects (2021). The choice of countries was determined by geography (with the aim of covering different continents), and considering some historical and political characteristics (EU countries, former Soviet Union countries), which allowed us to demonstrate that incorporation of ecocide in domestic laws was done under different approaches.

The second task was to consider international legal instruments to prevent the crime of ecocide. The provisions of a number of existing conventions within the Council of Europe and the UN frameworks were analyzed. For this part of the study we analyzed the Convention on Civil Liability for Damage resulting from Activities Dangerous to the Environment (Council of Europe, 1993); Convention on the Protection of the Environment through Criminal Law (Council of Europe, 1998); Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats (Council of Europe, 1979); Council of Europe Landscape Convention (Council of Europe, 2016), Recommendation CM/Rec(2022)20 of the Committee of Ministers to member states on human rights and the protection of the environment (Council of Europe, 2022a), Resolution “Environmental impact of armed conflicts” (Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, 2023), United Nations Convention on the Prohibition of Military or Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques (ENMOD Convention) (United Nations, 1976), Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of August 12, 1949, and Relative to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I) (United Nations, 1977), Guidelines on the Protection of the Natural Environment in Armed Conflicts (International Committee of the Red Cross, 2020). Based on the analysis of the texts of these international acts, conclusions were drawn regarding the completeness of coverage of environmental protection concerns by international law.

The third stage of the study was the analysis of information on the damage caused to Ukraine's environment during the full-scale invasion. The analysis was based on the reports of the Prosecutor General’s Office of Ukraine (Espreso Global, 2023), the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources of Ukraine (2024), and the European Parliament Research Service (2023).

The fourth stage of the study was an analysis of the definition of ecocide proposed by a group of experts from Stop Ecocide International (2021) to be incorporated in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

4. Results

Today, criminal liability for ecocide is primarily provided for at the domestic law level. Article 441 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine defines ecocide as “mass destruction of flora or fauna, poisoning of the atmosphere or water resources, as well as other actions that may cause an environmental catastrophe”, which is included in Chapter XX “Criminal Offenses against Peace, Security of Humanity and International Law and Order” (Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, 2001). Thus, Ukraine’s domestic law considers ecocide as a crime that goes beyond the crimes provided for in Chapter VIII “Criminal Offenses against the Environment” of the Criminal Code of Ukraine”. Considering that ecocide may be punished with a prison sentence from 8 to 15 years, Ukraine’s domestic law classifies it as a particularly serious crime. For ecocide criminal liability begins at the age of sixteen.

Ecocide also requires the subjective element of intent.

A resulting environmental disaster is not mandatory, though. The wording of the article in terms of the likelihood of such consequences indicates that liability arises for actions aimed at causing environmental disaster, regardless of whether this goal was achieved or not. Therefore, it is important to assess the possible consequences of the actions taken, because if they could not lead to an environmental disaster, the criminal classification will be different.

Speaking about the legal characterization of ecocide, it should be emphasized that it is a separate type of crime and cannot be considered as collateral damage in connection with military actions. For example, a case was opened due to the destruction of the Kakhovka HPP dam under Article 441 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine “Ecocide” and under Part 1 of Article 438 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine “Violation of the laws and customs of war” (Office of the Prosecutor General, 2023).

It should be noted that the practical aspects of applying the provisions of Article 441 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine cause certain difficulties, since the definition of ecocide contains a number of elements to be assessed that have not been disclosed and need to be specified. In particular, we are talking about the “mass destruction”, “poisoning”, and “environmental disaster” elements. On March 20, 2022, the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine adopted the Resolution “On Approval of the Procedure for Determining Damage and Losses Caused to Ukraine as a Result of the Armed Aggression of the Russian Federation” (Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, 2022). Different fields were identified when determining such damage, e.g.: damage to land resources; damage to water resources; damage to the atmosphere; losses of the forest fund; and damage to the nature reserve fund.

Based on this resolution, the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources of Ukraine has developed relevant methodologies, but they do not provide any definitions that would allow to clarify these elements. On the other hand, this statement refers only to the aspect that these acts do not solve the problems associated with the crime of ecocide. Nevertheless, they were not intended to do so, but rather to form a regulatory framework in terms of methodological grounds for determining the amount of damage caused to the environment as a result of military operations.

When analyzing the laws of foreign countries, the definition of ecocide that is closest to that in Ukraine law is found in the legislation of post-Soviet countries. This is quite understandable from a historical and political point of view, particularly if we consider the fact that these countries were deemed as part of a single space during the Chornobyl disaster in April 1986. For example, Article 136 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Moldova (2002) defines ecocide as “intentional mass destruction of flora or fauna, poisoning of the atmosphere or water resources, as well as other actions that may lead to, or have led to an environmental disaster”. An almost identical definition is provided by Article 394 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Armenia (2003), which defines ecocide as “intentional mass destruction of flora or fauna, poisoning of the atmosphere, land or water resources, as well as committing other acts that have caused an environmental catastrophe.

Article 342 of the Penal Code of Vietnam (Ministry of Justice of Vietnam, 1999) includes ecocide among crimes against humanity, stating that “persons who, in peacetime or wartime, commit any acts aimed at the mass destruction of the population of a certain territory, the destruction of its sources of livelihood, the undermining of the cultural and spiritual life of the country, undermining the foundations of society with the aim of undermining such society, as well as other acts of genocide or acts of ecocide or destruction of the natural environment, shall be punished with imprisonment from ten to twenty years, life imprisonment or the death penalty”.

At the same time, there is no single approach to the criminalization of ecocide at the domestic level. The legislation of most countries does not distinguish ecocide as a separate criminal offense, considering it to be part of crimes against humanity or against the environment, and choosing the path of international legal criminalization of ecocide (Orobets, 2022; Shatilo et al., 2023). For example, the Law on Combating Climate Change and Strengthening Resilience to its effects (2021), adopted in France on August 21, 2021, strengthens national liability for crimes that “cause serious and lasting damage to health, flora, fauna, or the quality of air, soil, or water” and obliges the government to take steps to recognize ecocide as an international crime with the possibility of prosecution by the International Criminal Court. Thus, the incorporation of ecocide as a crime in the domestic laws does not fully solve the problem of criminal liability for these acts, because, firstly, there is no single approach, and, secondly, it is a matter of damage to the environment on a scale that has global consequences.

Speaking about the possibilities of international legal instruments, attention should be paid to the already existing international legal instruments aimed at protecting the environment, but not all of them include the issue of such protection during armed conflicts. The legal instruments of environmental protection at the European level include the relevant conventions of the Council of Europe, namely the Convention on Civil Liability for Damage Caused by Activities Hazardous to the Environment (Council of Europe, 1993); Convention on the Protection of the Environment through Criminal Law (Council of Europe, 1998); Convention on the Conservation of Wild Flora and Fauna and Natural Habitats in Europe (Council of Europe, 1979); Council of Europe Landscape Convention (Council of Europe, 2016). From the point of view of ecocide -in general-, and ecocide during hostilities -in particular-, these conventions do not apply, as they either fail to explicitly indicate that any damages caused by armed conflicts fall under their scope of regulation or they explicitly indicate that such damage is not covered by them. For example, Article 8 of the Convention on Civil Liability for Damage Caused by Activities Hazardous to the Environment (Council of Europe, 1993) indicates that any damages caused by military operations (including civil war) are exempted.

On the other hand, these conventions are useful sources of internationally defined concepts related to environmental issues, including the concepts of hazardous activities, hazardous substances, genetically modified organisms, micro-organisms, damage, remediation, preventive measures, environment, incident (Council of Europe, 1993).

It should also be noted that in 2022, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe announced the revision of the Convention on Environmental Protection by criminal law. The new text is expected to include the crime of ecocide as an international crime. It is noted that there is a need to create a global framework for criminal liability for ecocide, since establishing such liability only at the domestic level allows offenders to avoid prosecution by using the different approaches taken by different countries when defining ecocide (Council of Europe, 2022c). The draft convention replacing the European Convention on the Protection of the Environment through Criminal Law (ETS No. 172) is expected to be completed by June 30, 2024.

The Council of Europe is gradually increasing its attention to the problems associated with damages caused to the environment by armed conflicts. For example, this is mentioned in Recommendation Rec (2022)20 of the Committee of Ministers to member states on human rights and environmental protection of September 27, 2022 (Council of Europe, 2022a). The next step was the adoption of the Resolution “The Impact of Armed Conflict on the Environment” (Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, 2023). The Resolution points out the irreversible nature of the damage caused by armed conflicts to the environment, the possibility of its spread to territories far beyond the armed conflict, and the potential violations to human rights such as the right to life, the right to health and the right to a safe environment. In determining that states involved in armed conflicts have substantive and procedural obligations under humanitarian law, the General Assembly pointed out that extraterritorial obligations may also arise during armed conflicts. Likewise, it emphasizes that the protection of the environment from the impact of armed conflicts is incidental to humanitarian imperatives. Thus, the Council of Europe’s position on environmental damage caused by armed conflicts is anthropocentric, which essentially reflects the goals of this international institution (Kharytonov et al., 2023).

When it comes to legal instruments for environmental protection at the UN level, the UN Convention on the prohibition of military or any other hostile use of environmental modification techniques (ENMOD Convention) should be mentioned first. In addition to the general declarative provisions on the inadmissibility of hostile environmental modification, the Convention provides a definition of environmental modification techniques (Article 2), which are defined as “the deliberate manipulation of natural processes that lead to a change in the natural dynamics, composition or structure of the Earth, including its biota, lithosphere, hydrosphere and atmosphere, or outer space” (United Nations, 1976). The Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of August 12, 1949, and Relative to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I) also contains certain provisions on the protection of the environment during armed conflicts.

In particular, Article 35(3) stipulates that “it is prohibited to employ methods or means of warfare which are intended, or may be expected, to cause widespread, long-term and severe damage to the natural environment”. Similar provisions are contained in Article 55, “Protection of the Natural Environment,” which also emphasizes the need to protect the natural environment during hostilities and the prohibition of damaging nature as a means of reprisal (United Nations, 1977).

We should also mention the Guidelines on the Protection of the Natural Environment in Armed Conflict (International Committee of the Red Cross, 2020), which, in addition to general guidelines, contain a significant number of evaluative concepts.

Thus, we can say that there is an extensive system of international legal tools aimed at protecting the environment, including during military operations. The approaches introduced in these international laws should be taken into account when implementing an international criminal law mechanism for defining and prosecuting ecocide, which should become a separate type of crime, taking into account additional aspects for each specific case.

Russia's actions have produced a devastating impact on the environment. As of November 2023, 271 cases related to crimes committed by the Russian Federation against the environment in Ukraine were under investigation, as well as 15 cases of ecocide (Espreso Global, 2023). In just two years of full-scale invasion, the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources of Ukraine (2024) reported about $63 billion in damages to Ukraine's environment. These figures are constantly growing, affecting the environment of neighboring countries as well. Damages include air pollution, waste pollution, water and soil pollution. The direct damage has been caused by the destruction of infrastructure and industrial facilities. At the same time, experience shows that there is no effective tool that could be used to obtain at least compensation for the damage caused.

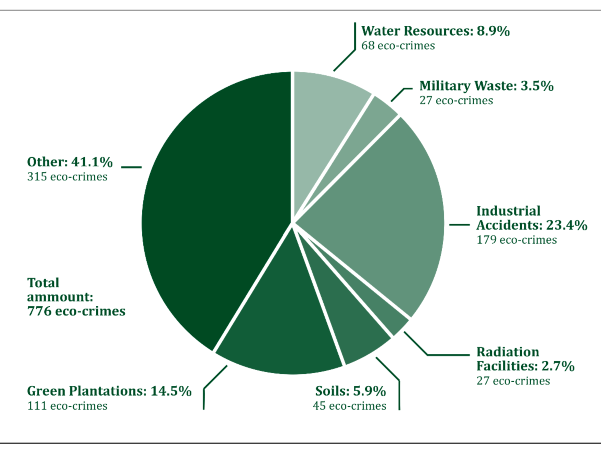

Even such an obvious crime of the Russian Federation as the destruction of the Kakhovka dam are difficult to prosecute. Experts point out that even if there are legal grounds (United Nations, 1977), the question of classification remains open: in terms of intentional actions, it is a violation of the positive obligation to protect civilian infrastructure, and in terms of deliberate actions, it is an act of indiscriminate violence (European Parliament Research Service, 2023). Furthermore, the prospect of bringing Russia to justice for environmental crimes is not affected by the lack of international regulation itself, but by the lack of an effective mechanism to prosecute the offenders to justice. It should be noted that in March 2022, Russia's membership in the Council of Europe was suspended (Council of Europe, 2022b). It continues to be a member of the UN, but this in no way restrains it from violating relevant international agreements. According to the SaveEcoBot system, as of March 2024, 762 environmental crimes committed by the Russian Federation in Ukraine were recorded (Figure 1).

Source: Developed by the authors according to the SaveEcoBot system (SaveEcoBot, 2024)

Figure 1. War crimes of the Russian Federation against the environment in Ukraine

The absence of a concept of ecocide and its definition as a separate crime is a real problem for modern international criminal law. The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court contains only the provision of Article 8 “War Crimes” on “intentionally launching an attack in the knowledge that such attack will cause (…) widespread, long-term and severe damage to the natural environment which would be clearly excessive in relation to the concrete and direct overall military advantage anticipated” (International Criminal Court, 1998).

The definition of ecocide, along with the consolidation of some evaluative concepts, was developed by a group of experts from Stop Ecocide International, who proposed to supplement the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court with Article 8 ter “Ecocide” as follows: “For the purposes of this Statute, ‘ecocide’ means unlawful or wanton acts committed with knowledge that there is a substantial likelihood of severe and either widespread or long-term damage to the environment being caused by those acts.

For the purposes of paragraph 1:

“Wanton” means with reckless disregard for damage which would be clearly excessive in relation to social and economic benefits anticipated;

“Severe” means damage which involves very serious adverse changes, disruption or harm to any element of the environment, including grave impacts on human life or natural, cultural or economic resources;

“Widespread” means damage which extends beyond a limited geographic area, crosses state boundaries, or is suffered by an entire ecosystem or species or a large number of human beings;

“Long-term” means damage which is irreversible or which cannot be redressed through natural recovery within a reasonable period of time;

“Environment” means the earth, its biosphere, cryosphere, lithosphere, hydrosphere and atmosphere, as well as outer space.” (Stop Ecocide International, 2021).

The proposed definition can generally be considered as one that will allow bringing offenders to justice for the crime of ecocide. A positive aspect is the alternative “illegal or intentional actions”, which allows criminalizing also unintentional actions or actions whose intentional nature cannot be proved. Another positive aspect is the possibility to prosecute actions that have a substantial likelihood of damage.

5. Discussion

Speaking about the definition of ecocide as a separate type of crime, Olivi (2022) points out the need to go beyond any comparisons with similar crimes, and to conduct a qualitative analysis of all elements. As the study has shown, the theoretical framework of ecocide should be based on a combination of approaches applied to human rights violations and environmental crimes, as well as war crimes in characterizing specific types of ecocide. We should agree with Cusato and Jones (2023), who point out that the movement to criminalize ecocide at the international level indicates a new approach when it comes to finding ways to counteract global problems. Indeed, the existing international legal mechanisms for environmental protection have proven to be ineffective, especially in times of war, when the provisions of international law are openly ignored. The war in Ukraine is yet another proof of this. Although there is no need to abandon the existing environmental protection mechanisms, the government should ensure accountability for ecocide, regardless of whether countries are part of certain conventions or international organizations, or bound by related obligations.

Furthermore, approaches to the ways in which liability for ecocide should be introduced differ nowadays. Thus, Robinson (2022) considers the criminalization of ecocide at the international level primarily as a deterrent tool based on a combination of criminal and environmental law. It is controversial to argue that different approaches are possible: the introduction of criminal liability for ecocide at the international level, or the creation of a group of states that support this idea at the initial stage. The present study shows that this second approach has already proven to be ineffective when it comes to the adoption of relevant legislation at the domestic level.

One of the most debated issues is also the definition of a victim of ecocide. Different positions are expressed in this regard, including the recognition of nature as an independent subject of relevant legal relationships. The author emphasizes that the division into humans and nonhuman beings from the perspective of ecocentrism should be considered artificial. Frisso (2023) points out that when recognizing nature as a victim of the crime of ecocide, a distinction should be made between the victim’s right to participate in the process and the victim's right to reparation, as provided for in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. Proponents of the other position emphasize the need to move away from an anthropocentric approach to understanding the crime of ecocide and promote the thesis that the natural environment is a value not only in connection with human life, but also in itself. In this regard, proposals are made to consider it as a holder of rights. For example, criticizing the proposal of the Stop Ecocide International group to amend the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court to recognize ecocide as a new international crime, Winter (2023) draws attention to its anthropocentric nature, when the interests of the natural environment are not taken into account.

Bozkurt (2023) speaks about the need to grant the planet the right to self-determination and emphasizes the need for a “World Declaration of the Rights of the Planet”. Noting that ecocide is traditionally understood as a military tactic, which primarily connects it with war crimes, Kowalska (2023) draws attention to the gradual shift in the vector of attention towards ecocentrism, when ecocide is characterized as a transboundary threat, and nature is recognized as a “silent victim”. This position seems quite reasonable, because it recognizes that the environment is a basic component of the possibility of our existence. Thus, research should next aim at specifying the crime of ecocide, even when considering ecocide from the perspective of human existence.

6. Conclusions

The consequences of ecocide are global in nature. As a crime, ecocide may include elements of the crime of genocide, environmental crimes, and lead to human rights violations. However, it remains an independent type of crime, and its prosecution requires specific regulations. Nowadays, not all countries of the world have incorporated criminal liability for ecocide in their domestic law, and where it has been incorporated there are different approaches to the definition of ecocide. In domestic criminal law, ecocide is defined as a crime against humanity or as an environmental crime. However, this approach does not allow for the resolution of the issue of ecocide on a global scale, even though its consequences are global. The current international environmental regulatory system is ineffective, as relevant agreements do not bind all countries, and sometimes their provisions are simply ignored, as demonstrated by the actions of the Russian Federation during the war with Ukraine. While massive crimes against the environment may still be the subject of consideration by the International Criminal Court, there is virtually no mechanism to prosecute ecocide in peacetime.

Today, the most effective way to ensure criminal prosecution of ecocide is to include a corresponding provision in the Statute of the International Criminal Court. Despite the fact that the definition of ecocide proposed by Stop Ecocide International is subject to criticism, it contains provisions of fundamental importance, allowing prosecution even in the absence of direct intent to cause damage, and for actions aimed at causing damage to the environment.

Ukraine is currently going through the practical experience of prosecuting the crime of ecocide. Although the methodology for assessing the damage caused to the environment by the actions of the Russian Federation proposed by the Government of Ukraine does not provide an opportunity to clarify the evaluative concepts of ecocide contained in its domestic law, it can be used to further improve the mechanism to determine the compensation, including the environment as a victim of the crime of ecocide.