Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO  uBio

uBio

Share

Revista Peruana de Biología

On-line version ISSN 1727-9933

Rev. peru biol. vol.23 no.1 Lima Jan./Apr. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/rpb.v23i1.11834

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/rpb.v23i1.11834

NOTA CIENTÍFICA

Small vertebrates in the spectacled bear’s diet (Tremarctos ornatus Cuvier, 1825) in the north of Peru

Pequeños vertebrados en la dieta del oso andino (Tremarctos ornatus Cuvier, 1825) en el norte del Perú

Fiorella N. Gonzales1,2*, Javier Neira-Llerena2, Gabriel Llerena1,2 y Horacio Zeballos1,3

1 Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad Nacional de San Agustín. Av. Alcides Carrión s/n, Arequipa, Perú.

2 Asociación para la Investigación y Conservación ZOE, Arequipa. Urb. Casa de campo A-33. Sachaca, Arequipa, Perú.

3 Instituto de Ciencias de la Naturaleza, Territorio y Energías Renovables, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. Av. Universitaria 1801, San Miguel, Lima 32, Lima, Perú.

Abstract

There have been numerous studies about Spectacled bear´s diet, however little is known about the small vertebrates it consumes. This study present nine vertebrate species (seven rodent and two birds) as preys of the Spectacled bear, based on the analysis of six feces collected from two locations Upa (Amazonas) and Lagunas Arreviatadas (Cajamarca) in northern Peru. Six of these records were new food items and a new family Caviidae. Vertebrates were found only in the Upa location. Additionally a sampling of small non flying mammals was conducted in there. Our results suggest that the Spectacled bear would be a generalist species. It prefers plants, however if it finds vertebrates in the environment, it could feed on them.

Keywords: birds; diet; generalist; rodents.

Resumen

Se han realizado numerosos estudios acerca de la dieta del oso andino, sin embargo poco se conoce sobre los pequeños vertebrados que consume. El presente trabajo da a conocer nueve especies de vertebrados (siete roedores y dos aves) como presas del oso andino, por medio del análisis de seis fecas provenientes de dos localidades Upa (Amazonas) y Lagunas Arreviatadas (Cajamarca) en el norte de Perú. Seis de estos registros son nuevos ítems alimenticios y una nueva familia Caviidae. Tan solo en la localidad de Upa se encontraron restos de vertebrados. Adicionalmente los pequeños mamíferos no voladores fueron muestreados en esa localidad. Nuestros resultados sugieren que el oso andino sería una especie generalista, si bien puede tener preferencias en la ingesta de plantas, en el caso de los vertebrados pareciera consumirlos según los encuentra en el ambiente.

Palabras clave: aves; dieta; generalista; roedores.

Introduction

The Spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus) is endemic to the Andes, and it is the only bear species inhabiting South America. Its distribution in the Andes goes from the Merida mountain range west of Venezuela, through the Andes extends from Colombia, Ecuador, and Perú to the province of Porta in Bolivia (Peyton 1999, Figueroa & Stucchi 2009). Recently, its presence was confirmed in Argentina (Del Moral & Bracho 2009) and it could possibly inhabit Panama as well (Jorgenson 1984, Goldstein et al. 2008). It is estimated that from Venezuela to Bolivia there is a population of 20,000 individuals (Peyton et al. 1998). In Peru the population was estimated to be 5,700 individuals in 1999(Peyton et al. 1999), but there are no recent estimates.

It is considered a "flagship species" in the field of conservation due to its role in the ecosystem and its influence on the local population and culture (Peyton 1999). Information about their basic ecology and feeding have been studied in almost the entire range of their distribution (e.g., Peyton 1980 1984 1986, Poveda 1999, Paisley 2001, Castellanos 2006 2011 2012, Goldstein et al. 2008, Figueroa & Stucchi 2009, Figueroa 2013). The Spectacled bear is an omnivorous animal that can take advantage of any food resource, using an opportunistic strategy in the use of food resources. Most of studies mention Bromeliad plants as the main component in the bear’s diet (Peyton 1980, Peyton 1981, Suárez 1985, Azurduy 2000, Paisley 2001, Figueroa & Stucchi 2009, Rios-Uzeda et al. 2009, Figueroa 2013). It is possible that these species are a key resource in the bear’s subsistence. Peyton (1980, 1981, 1984) suggested that bears feed exclusively of the sprouts of these plants during the months in which other fruit species are not available. Being evident their preference for fruits of different species (Figueroa 2013). Its role as disperser is vital for the maintenance of several populations of trees species (Chapman & Chapman 1995); Rivadeneira-Canedo (2008) showed that the Spectacled bear disperser three plant species Nectandra cf. cuneatocordata, Symplocos cf. cernuay and Gaultheria vaccinioides in Bolivia, other species disperser are Nectandra sp. and other Lauraceaes (Peyton 1984, 1987), Styrax ovatus (Styracaceae)(Young 1990) and Inga sp. (Fabaceae) (Figueroa & Stucchi 2003) in Peru and other Lauraceae species Ocotea sp. in Colombia Rodríguez et al (1986). However, the Bromeliad plants contain low protein and nutritional values (Paisley 2001). This low quality food would be compensated with animal consumption. Figueroa (2013) suggested that animal consumption in the bear’s diet is less than 10%, and makes a review of animal species that consumes the bear in South America, reporting that 34 species are consumed at least including mammals, birds, insects, molluscs and annelids. Being Peru the country with more records of animals eaten by the bear (19 ssp.), followed by Colombia (14 spp.), Bolivia (12 spp. and a hybrid: mule), Venezuela (10 spp.) and Ecuador (eight spp.) Figueroa (2013).

This study discloses some vertebrate species as Spectacled bear's preys, based on the analysis of feces collected in two locations of northern Peru. This knowledge about the trophic niche of this bear species help us to understand the importance of the big mammals like predator and this could be used as basic information for conservation plans. It also emphasizes the value of studying mammal’s feces to complement ecology studies despite its limitation.

Materials and methods

Vertebrates content was analyzed in six separate samples of Spectacled bear feces collected from two locations in Peru. The first collection was in October 2009 in the surroundings of Lagunas Arreviatadas, located in the high basin of Tabaconas River, Tabaconas district (Cajamarca department), south of the National Sanctuary Tabaconas Namballe. It belongs to the pluvial montane tropical forest (b-MT) Holdridge life zone (Holdridge 1967). This is a lagoon complex located in the Páramo ecosystem, characterized by scrublands, groves of Podocarpus sp. and grasslands in the hillsides and gorges (Amanzo et al. 2003), located at 05º14'12,8"S and 79º16'49,2"W, altitude 3000 - 3300 m. In this place we collected three fecal samples. Three more fecal samples were colleted in March 2012 at the location of Upa (6°0'08.84"S and 77°49'21.87"W; altitude 3000 - 3500 m) in the Yurumarca annex, Province of Chachapoyas (Amazonas department). The area corresponds to the high basin of Gocta waterfall, where Jalca is the prevailing vegetation formation (Mostacero et al. 1996, Sánchez-Vega et al. 2006) and it belong to the life zone of low mountain dry forest (bs-MB) according to Holdridge (1967). This is an ecosystem where scrublands prevail with small forest patches and grasslands on the sides, abundant water, and variable topography with high and low hills. We can also observed burned areas and cattle.

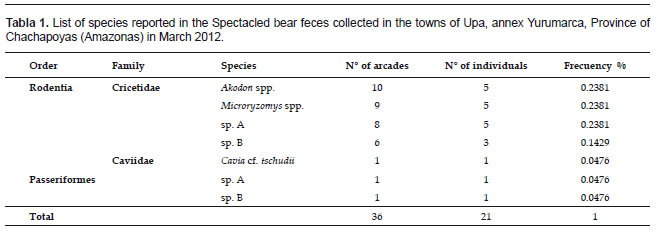

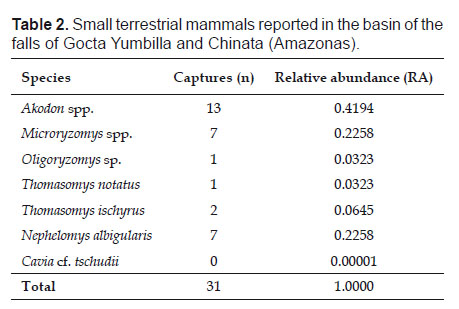

Feces were preserved with a wet method (70% alcohol) and dispersed by decantation following the considerations of Korschgen (1987). Only vertebrate fauna was analyzed and species determination was done through comparison with mammal and bird samples from scientific collection of the Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad Nacional de San Agustin de Arequipa. Bone remains of vertebrate fauna were found in two out of the six feces samples, which were found in the location of Upa (Amazonas department). They included bone remains of limbs, vertebrae, upper and lower jawbones, tails, feet, and hair for rodents. While for birds, they included two tarsi of different sizes, one premaxilla and lungs. A tooth and a femur corresponding to a caviomorph were also found. A sampling of small non flying mammals was conducted in the location of Upa (Yurumarca annex) in March 2012. We used box traps (80 Sherman and 26 Tomahawk) and 18 pitfall traps. The traps remained open for four days, totaling an effort of 3228 traps/night and 144 buckets/night. Traps were baited with a mixture of oats, vanilla, canned fish, and banana essence cassava chips. Of all captured specimens, reference specimens for the study area were collected, the rest were freed, the collected specimens were preserved as study skins or alcoholic samples as the methodology set by Lopez et al. (1998). The taxonomic identity of the captured specimens were determined with the help of taxonomic keys (Anderson 1997, Emmons & Feer 1999, Eisenberg & Redford 1999). We calculated the frequency of occurrence (F %) of each species (item) identified in the feces of the Spectacled bear (Table 1).

Based on the relative abundance of each mammal and the total number of individuals collected in the location of Upa (Table 2) we obtained the frequency of occurrence for each species. A Chi square test was made to compare the frequency of occurrence of mammals species present in the feces and the relative abundance of small mammals species collected in the locality of Upa. This test would be used as an indicator to characterize strategies of predation, if it is generalist or specialist species (Jaksic & Marone 2007).

Results and discussion

A total of seven vertebrate species was determined, from which five belonged to the order Rodentia and two to the order Passeriformes. The most abundant species were Akodon spp., Microryzomys spp. and two species of unidentified rodents. All cricetids with a frequency of 0.86% (Table 1).

If the proportion of available animals and consumed prey is known we can determine if a predator is opportunistic or if it has a preference for a specific resource (Jaksic & Marone 2007). With the results, we compared the prey in the bear’s diet with the abundance of small mammals captured in the surroundings of Yurumarca annex. There was not a significant difference between the proportion of species found in feces and relative abundance of prey captured, which could indicate it is an opportunistic diet t (X2 = 0.9271, df = 6, p = 0.05).

It is known that the Spectacled bear in Peru consumes small mammals like rodents, rabbits and larger mammals such as deer and sloth (Peyton 1989). Likewise, Figueroa (2013) presented a review of the Spectacled bear’s diet in South America, where 24 vertebrate species were reported to be consumed including one bird species and 23 mammals, of which eight were domestic. However, regarding the consumption of rodents for Peru, the only reported a single remains in a fecal sample collected in the National Park Yanachaga Chemillén (Oxapampa)(Figueroa 2013). Previously, only two identified species of the order Rodentia had been reported to be consumed by the Spectacled bear, Thomasomys in Ecuador (Suárez 1985) and Lagidium peruanum "Vizcacha" (PAHS 1995 cit. Rivadeneira 2001) in Bolivia, as well as non-identified micromammals (Paisley 2001). Regarding bird remains have been reported in Ecuador (Suárez 1985), Bolivia (Pasley 2001) and Peru (Peyton 1980), but no species have been identified. This is because birds have hollow bones that are easily destroyed by the bear’s gastric fluids.

Most of the studies highlight the importance of the Spectacled bear as a seed disperser (Rivadeneira-Canedo 2008, Azurduy 2000, Young 1990), but its role as a predator has been little studied, possibly because it is difficult to quantify the prey consumption. Some studies used indirect methods (semi-structured interviews) made to local people, to obtain information about the number of domestic cattle that are attacked by the bear in a particular time and place; focus more on the issue of Spectacled bear-human conflict (e.g., Figueroa 2015, Castellanos & Laguna 2012, Castellanos et al. 2011, Parra-Romero 2011, Jorgensen & Sandoval 2005, Poveda 1999) than on their role as predator.

In this study we expand the knowledge about the Spectacled bear diet’s, by at least seven rodent and two bird species. Six of these records are new food items in the bear’s diet and a new family Caviidae with the species Cavia cf. tschudii.

In the present study it is important to notice the numeric presence of rodents found in the feces samples, this could be because usually the humid season is when there are more availability of resources and when most small mammals are breeding coinciding with the season of this study; in addition, a preliminary biodiversity inventory done in the study area reported 39 mammal species, with Rodentia being the most abundant order (15 species) (Zeballos et al. 2016 unpublished data) (Table 2). It is possible that the consumed food items of animal origin as well as plant origin, could vary between humid and dry season as reported by Peyton (1980) and Azurduy (2000).

Figueroa (2013) points out that the animal matter consumed by the Spectacled bear would represent a high level of proteins and energy, although, she only considers some large mammals (lama, deer, pig, sheep, goat, rabbit, lowland paca, and cow) indicating that the protein and energy level would be 14,4 - 57,7 g/100 g and 105 - 279 Kcal/100 g. In our case, we could extrapolate the data of protein and energy content for Cavia cf. tschudii with the data from Cavia porcellus "guinea pig" that is 96 kcal/100g and 19,0g/100g (INS 2009), since they are similar species in size, biomass and phylogenetic closeness. Starting from the idea that the optimal diet for a Spectacled bear in captivity from 60 to 140 kg, is estimated to consume between 3100 and 5700 kcal per day (Dierenfeld 1989 cit. Figueroa 2013), the energy of a medium size rodent as the "guinea pig", with an average weight of 800 kg does not represent a significant nutritional contribution in the bears diet, possibly it has to consume more than six rodents with similar characteristics to guinea pig, to meet energy demand of animal matter; and least of all if we take in consideration the other six cricetids rodents (Table 1), probably their energy and protein values are insignificant in the bear diet. In addition the requirements of a bear in the wild would be much higher, depending mainly on their nutritional requirements, seasonality, age, sexual maturity. However Eagle & Pelton (1983) shows that the consumption of small volumes of different species of animals could compensate the nutritional requirements, as well as providing some essential aminoacids. Probably the bear would hunt occasionally some large vertebrates to offset their protein requirements; on the other hand Dierenfeld (1989) cit. Figueroa (2013) suggests that it is possible that the low consumption of animal matter by the bear is reflected in the low levels of urea in its blood and this could indicate that this species just like the Great Panda bear is adapted to low nitrogen diets and/or metabolism is different.

There is a high diversity of plant species in the Páramo in the location of Las Arreviatadas (Cajamarca) that consists of 128 species and 37 families. The most diverse families are Poaceae, Melastomataceae, Ericaceae and Orchidaceae (Marcelo & La Torre 2006) which is why we would expect a higher availability of food resources for the Spectacled bear than in Jalca (Amazonas). This could explain the lack of animal matter remains in the feces coming from this location. A study of the Spectacled bear’s diet in the Ecuadorian Páramo (Suárez 1985) found animal remains in its diet and it indicated that 96% of the evidence of food recognized in the field corresponds to Bromeliad plants remain, from that, 85% were Puya sp. This would indicate once again that the Spectacled bear is an animal mainly vegetarian, but it occasionally consumes animal matter. Our data suggests that the Spectacled bear is an generalistic species, which is similar to other authors’ conclusion (Peyton 1980 1984, Suárez 1988, Rivadeneira-Canedo 2008, Figueroa & Stucchi 2002). The bear has preference for plants, but it could consume vertebrates if found.

Complement the data regarding the bear’s natural history is necessary to plan an adequate management and improve the conditions of its conservation, as well as the associated biodiversity; that is why it is important to continue studying this species diet. Feces are, therefore, a very useful tool to study the animals’ diet since the analysis of the samples is easy and relatively reliable (Korschgen 1987), although the method has certain disadvantages such as problems with the correct identification of prey remains, the absence of chitinous and bone remains influenced by preys size and predator digestibility, the remains (feathers, hair) do not allow identify more than one individual, among others. The sample size is also important, our sample is very small and possibly only represents an event in the trophic ecology of the Spectacled bear.

It is necessary a more detailed assessment of this species diet of one year at least to examine seasonal differences, consumed preys and complete a detailed list taking into account the animal and plant material.

Acknoledgements

We would like to thank Elízabeth Terán who directed the Program for rural development in Amazonas of the Cooperación Alemana (GIZ), which funded the sample collections. We would also like to thank the Dirección Forestal y Fauna Silvestre for the wildlife sampling permit (RD 129-2013-AG-DGFFS-DGEFFS) in the area of the Gocta waterfall. Finally, thanks to Alexander Pari for his field assistance, Denis Alexander Torres for the bibliography and Laura Morales for the review and contributions to the manuscript.

Información sobre los autores:

FNG, GLLR, HZP y JNLL realizaron el diseño experimental; HZP: realizó los muestreos en campo y colectó las muestras; FNG, GLLR, HZP y JNLL analizaron los datos; FNG, GLLR, HZP y JNLL redactaron el manuscrito; FNG, JNLL, GLLR, HZP revisaron y aprobaron el manuscrito.

Los autores manifiestan que no existe conflicto de intereses de ningún tipo.

Permisos de colecta:

Dirección Forestal de Flora y Fauna Silvestre - permisos de recolección No. 0840129-20122013-AG-DGFFS-DGEFFS.

Literature cited

Amanzo J., R. Acosta., C. Aguilar., K. Eckhardt., S. Baldeón & T. Pequeño. 2003. Evaluación biológica rápida del Santuario Nacional Tabaconas-Namballe y zonas aledañas. INRENA & WWF-OPP. Lima. http://wwfperu.pe/documentos/bosques/InformeFinal SNTN.pdf [ Links ]

Azurduy C.L. 2000. Variación y composición alimentaria el oso andino (Tremarctos ornatus Cuvier 1825) en época seca y lluviosa en la cuenca alta del río Cañón y zonas adyacentes. Tesis para optar el grado de licenciatura en biología, Universidad Mayor de San Simón, Cochabamba, Bolivia. [ Links ]

Anderson S. 1997. Mammals of Bolivia, Taxonomy and Distribution. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 231: 1 - 652. [ Links ]

Castellanos A. & A. Laguna. 2012. Depredación a ganado vacuno y mamíferos silvestres por oso andino en el norte de Ecuador. Pp. 112 en Memorias del X Congreso Internacional de Manejo de Fauna Silvestre en la Amazonía y América Latina. Salta, Argentina. [ Links ]

Castellanos A. 2011. Do Andean bears attack mountain tapirs? International Bear News 20:41–42. [ Links ]

Castellanos A. 2006. Canibalism in Andean Bears? International Bear News, Quaterly Newsletter of the International Association for Bear Research and Management (IBA) and the UICN/SSC Bear Specialist Group. 15(4):20. [ Links ]

Chapman C. & L. Chapman. 1995. Survival without dispersers: seedling recruitment under parents. Conservation Biology, 9:675-678. [ Links ]

Del Moral J.F. & A.E. Bracho. 2009. Indicios indirectos de la presencia de oso andino (Tremarctos ornatus Cuvier, 1825) en el noroeste de Argentina. Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales, 11(1):69-76. [ Links ]

Eisenberg J. F. & K. H. Redford. 1999. Mammals of the Neotropics, the central Neotropics Vol. 3: Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil. The University of Chicago Press. Chicago. [ Links ]

Emmons L.H. & F. Feer. 1999. Mamíferos de los Bosques Húmedos de América Tropical: una guía de campo. Editorial F.A.N. Santa Cruz de la Sierra. Bolivia. [ Links ]

Eagle T.C. & M.R. Pelton. 1983. Seasonal nutrition of black bears in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. International Conference on Bear Research and Management 5:94–101. [ Links ]

Figueroa J.2015. Interacciones humano-oso andino Tremarctos ornatus en el Perú: consumo de cultivos y depredación de ganado. Therya online 6(1): 251-278. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2007-33642015000100251&lng=es. http://dx.doi.org/10.12933/therya-15-251 [ Links ]

Figueroa J. 2013. Revisión de la dieta del oso andino Tremarctos ornatus (Carnivora: Ursidae) en América del Sur y nuevos registros para el Perú. Rev. Mus. Argentino Cienc. Nat., N.S. 15(1):1-27. [ Links ]

Figueroa J. & M. Stucchi. 2009. El oso andino: alcances sobre su historia natural. Asociación para la Investigación y Conservación de la Biodiversidad-AICB. Primera Edición. Lima, Perú [ Links ].

Figueroa J & M. Stucchi. 2003. Presencia del oso andino (Tremarctos ornatus) en los bosques secos de la Zona Reservada Laquipampa y áreas adyacentes, Lambayeque. I Congreso Internacional de Bosques Secos. Piura Perú [ Links ].

Goldstein I.R., V. Guerrero & R. Moreno.2008. Are These Andean Bears in Panama?. Ursus 19:185-189. [ Links ]

Goldstein I. 1986. Research on the spectacled bear in Venezuela. Pp: 48. In: Weinhardt, D. (ed.). International Studbook for the Spectacled Bear 1985. Lincoln Park Zoological Gardens, Chicago, USA. [ Links ]

INS (Instituto Nacional de Salud). 2009. Tablas peruanas de composición de alimentos. Ministerio de Salud, Perú, 64 pp. [ Links ]

Jaksic F. & L. Marone. 2007. Ecología de comunidades, Segunda edición ampliada, Ediciones Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago. 336 pp. [ Links ]

Jorgenson J. 1984. Informe de países: Colombia. Bol. Geof.7:13 [ Links ]

Korschgen L. J. 1987. Procedimientos para el análisis de los hábitos alimentarios. Pp. 119-134, en: T. R. Rodríguez (ed.). Manual de técnicas de gestión de vida silvestre. The Wildlife Society, Inc. Washington, D.C. [ Links ]

López E., A. Morales, E. Ponce & S. Rivera. 1998. Preparación de taxidermias de vertebrados para estudio e investigación. Universidad Nacional de San Agustín. Arequipa, Perú 89 pp. [ Links ]

Lozada R. 1990. A Survey of the Status and Distribution of the Spectacled Bear in the Western Range of the Colombian Andes. P. 190. [ Links ]

Marcelo J. & M. La Torre. 2006. Flora y vegetación del Páramo adyacente a las lagunas Arreviatadas, Santuario Nacional Tabaconas Namballe. Proyecto Elaboración de la Ficha Ramsar Las Arreviatadas (Santuario Nacional Tabaconas–Namballe) http://cdc.lamolina.edu.pe/Descargas/anp/expediente_arreviatadas.html. [ Links ]

Parra-Romero A. 2011. Análisis integral del conflicto asociado a la presencia del oso andino (Tremarctos Ornatus) y el desarrollo de sistemas productivos Ganaderos En áreas De amortiguación del PNN Chingaza. Trabajo de grado para optar el título de bióloga. Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá. http://repository.javeriana.edu.co/bitstream/10554/8879/1/tesis816.pdf [ Links ]

Paisley S. 2001. Andean bears and people in Apolobamba, Bolivia: culture, conflict and conservation. Dissertation, Durrel Institute of Conservation and Ecology, University of Kent, Canterbury, UK. [ Links ]

Poveda J.J. 1999. Interacciones ganado–oso andino Tremarctos ornatus (F. Cuvier, 1825) en límites de cinco municipios con el Parque Nacional Natural Chingaza: una aproximación cartográfica. Tesis de Licenciatura, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Facultad de Ciencias. Santa Fé de Bogotá, Colombia. [ Links ]

Peyton B. 1999. Spectacled bear conservation action plan. En: Bear Status survay and conservation action plan. Compiled by Christopher Servheen, Stephen Herrero & Bernand Peyton. UICN/SSC Bear Specialist Group. Switzerland and Cambridge, UK. 9: 157-198. [ Links ]

Peyton B., E. Yerena., D. Rumiz., J. Jorgenson & J. Orejuela. 1998. Status of wild Andean bears and policies for their management. Ursus 10:87-100. [ Links ]

Peyton B. 1987. The bear in the eyebrow of the jungle. Animal Kingdom. Marzo/Abril. 90(2): 38-45. [ Links ]

Peyton B. 1984. Spectacled bear hábitat use in the Historical Sanctuary of Machu Picchu and adjacent areas. M.S. Thesis, University of Montana, Missoula. [ Links ]

Peyton B. 1981. Spectacled bears in Peru. Oryx 16:48-56. [ Links ]

Peyton B. 1980. Ecology, Distribution and Food Habits of Spectacled Bears, Tremarctos ornatus, in Perú. J. Mammalogy 61(4):639-652. [ Links ]

Rios-Uzeda B., G. Villalpando., O. Palabral & O. Alvarez. 2009. Dieta de oso andino en la región alta de Apolobamba y Madidi en el Norte de La Paz, Bolivia. Ecología en Bolivia 44(1):50-55. [ Links ]

Rivadeneira C .2001. Dispersión de semillas por el oso andino (Tremarctos ornatus) y elementos de su dieta en la región de Apolobamba-Bolivia. Tesis de Licenciatura, Universidad Mayor de San Andrés, Bolivia. [ Links ]

Rivadeneira-Canedo C. 2008. Estudio del oso andino (Tremarctos ornatus) como dispersor legítimo de semillas y elementos de su dieta en la región de Apolobamba-Bolivia, Ecología en Bolivia, Vol. 43(1):29-39. [ Links ]

Rivera C. 2004. Caracterización preliminar de la dieta del oso de anteojos Tremarctos ornatus a partir del análisis de heces, en un sector de bosque andino del Parque Nacional Natural PISBA Boyacá. Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia. Facultad de Ciencias, Escuela de Biología. Tunja, Colombia. [ Links ]

Rodríguez E.D., F. Poveda, D. Rivera, J. Sánchez, V. Jaimes & L. Lozada. 1986. Reconocimiento preliminar del hábitat natural del oso andino y su interacción con el hombre en la región nororiental del Parque Natural El Cocuy. Boletin Divulgativo Manaba 1(1): 1-47. [ Links ]

Suárez L.1988. Seasonal distribution and food habits of Spectacled bears Tremarctos ornatus in highlands of Ecuador. En: Studies on neotropical fauna and environment. 23 (3): 133-136. En Red Tremarctos [ Links ]

Suárez L.1985. Hábitos alimenticios y distribución estacional del oso de anteojos, Tremarctos ornatus, en el páramo suroriental del volcán Antisana, Ecuador. Tesis previa a la obtención del título de licenciado en ciencias Biológicas, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Ecuador. [ Links ]

Young K. 1990. Dispersal of Styrax ovatus seeds by the Spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus).Vida Silvestre Neotropical 2(2): 68-69. [ Links ]

Presentado: 04/03/2015

Aceptado: 05/02/2016

Publicado online: 28/05/2016

*Autor para correspondencia

Email Fiorella N. Gonzales: nasharellas@yahoo.es

Email Javier Neira-Llerena: xavi_enri@hotmail.com

Email Gabriel Llerena: gallere_js@yahoo.es

Email Horacio Zeballos: horaciozeballos@gmail.com