Introduction

According to a classical description of the marine mollusk fauna of north Peru, the sandy beaches between Punta Pariñas in the north and the mouth of the Rio Chira in the south (21 km north of Paita, provincia Piura) are “generally devoid of much interest” to the malacologist, because they are dominated by a very small number of species (Olsson 1924, p. 122; see also Koepcke & Koepcke 1952). However, while habitats dominated by a few species may seem boring to taxonomists, they can be attractive to biologists interested in the behavioral ecology of those species. One of the abundant taxa on Olsson’s ‘uninteresting’ north-Peruvian beaches is Olivella columellaris G.B. Sowerby I, 1825, a species recently included in the genus Pachyoliva (Pastorino & Peters 2023).

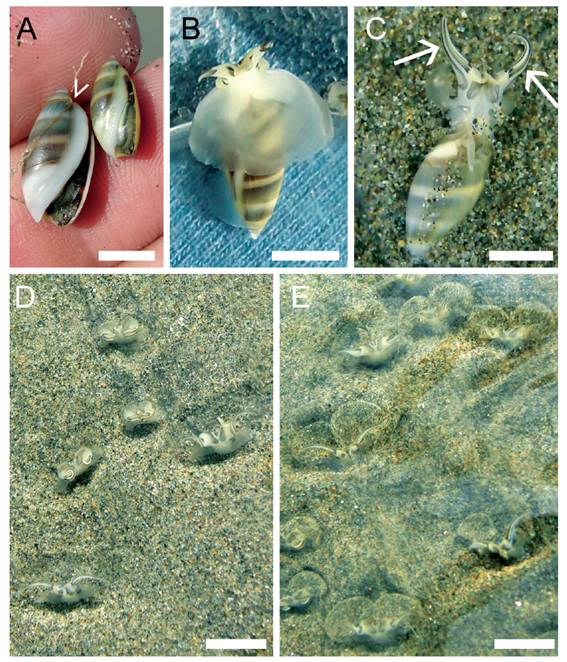

Pachyoliva columellaris shells are smooth and bullet-shaped as is typical of the Olivellinae (Olsson 1956, Kantor et al. 2017), reaching a maximum length of about 15 mm (Troost et al. 2012). When the animals grow to over 10−11 mm shell length, a thick columellar callus develops that extends beyond the posterior end of the aperture, generating a characteristic kink at the level of the first suture line above the aperture (Fig. 1A). Smaller individuals lack such pronounced callus (Fig. 1A) and are hard to distinguish from small P. semistriata, which may explain why the latter occurs regularly in Peruvian species lists (e.g. Paredes et al. 1999, Ramírez et al. 2003) although most if not all records of P. semistriata in Peru are apparently due to misidentifications (Troost et al. 2012; see also Peters 2022c). Pachyoliva columellaris utilizes water currents to move rapidly across its intertidal habitat. To do so, it expands its metapodium (posterior, main part of the foot) into a semi-circular skirt around the anterior shell (Fig. 1B). This skirt serves as an underwater sail (Peters 2022a,b). Schuster (1952) and Seilacher (1959) first reported this behavior from central American “Olivella columellaris”, which in fact was P. semistriata.

Figure 1 General features of Pachyoliva columellaris. (A) Animals of 12.8 mm (left) and 9.3 mm (right) shell length. The characteristic kink in the shell (arrowhead) caused by the thick spire callus develops when shells grow beyond ≈11 mm. (B) Snail in underwater-sailing posture, ventral view. The expanded foot forms a translucent skirt around the anterior part of the shell. (C) Specimen with expanded propodium, showing the elongate lateral appendages (arrows). (D) Suspension feeding in the backwash, flow from bottom to top. Propodial appendages are fully expanded in the animal in the lower left, and at various stages of retraction in all other specimens. The mucus sheets suspended from the appendages remain translucent when snails feed in smooth flow. (E) When sediment is swirled up in more turbulent flow, the hemispherical sheets become more clearly visible due to attached particles. Scale bars: 5 mm.

The propodium (anterior portion of the foot) of P. columellaris carries elongate lateral appendages (Fig. 1C) that are unique to the genus Pachyoliva. These appendages are used to deploy mucus sheets for collecting organic detritus and other edible materials from flowing water (Fig. 1D, E). The mucus sheets with any attached particles are eaten at short intervals. This suspension-feeding behavior is observed most frequently in the smooth backwash just below the water line, although it also has been reported to occur under appropriate flow conditions outside of the backwash zone (Morse & Peters 2016). In the natural habitat, huge numbers of animals are suspension-feeding in the backwash at all times. Field observations of P. columellaris feeding on live polychaetes suggest that this mollusk is capable of performing the unusual feeding mode switch between macrophagous carnivory and microphagous suspension-feeding (Peters et al. 2022). Such trophic versatility may explain the dominance of P. columellaris among the invertebrate communities of many North-Peruvian beaches.

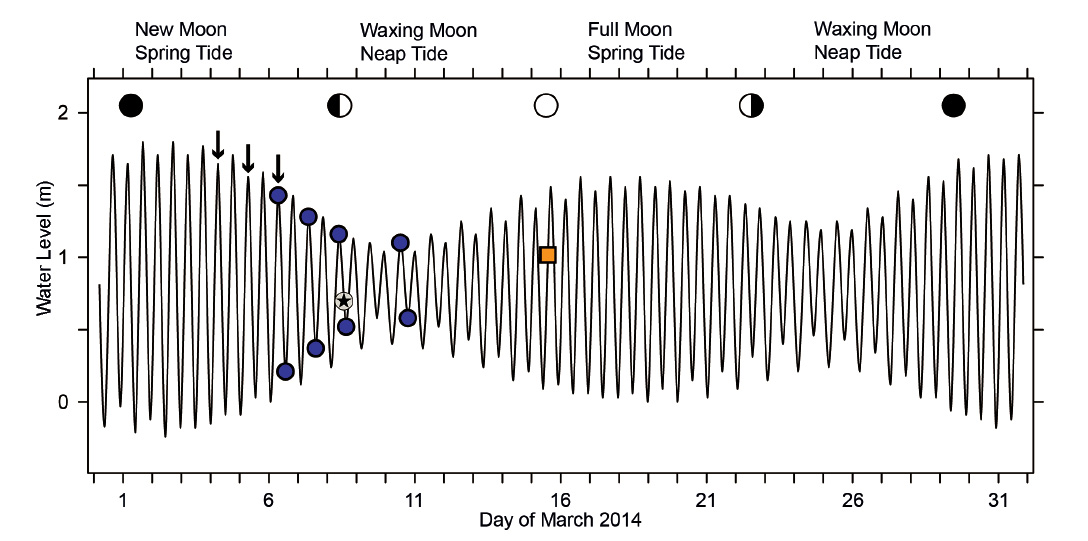

Animals that depend on food uptake in a narrow, hydrodynamically defined zone of tidal beaches may follow two strategies to deal with the tidal movements of that zone. Either they remain in one place, being active when conditions at that location allow feeding but passive when they are not. Alternatively, the animals may perform tidal migrations to follow the continuous movement of their feeding zone on the beach slope (for general discussion, see Gibson 2003, McLachlan & Brown 2006). Utilizing its capacity for rapid locomotion by underwater-sailing, P. columellaris applies the latter strategy (Peters et al. 2022). Based on laboratory tests, this behavior had been inferred to be governed by an endogenous clock (Vanagt et al. 2008), but field observations of animals under unusual conditions suggested that tidal migrations by underwater-sailing locomotion are triggered by changing external conditions in this species (Morse & Peters 2016). Generally, our knowledge of the tidal migrations performed by invertebrates like P. columellaris is remarkably poor. For example, tides in north Peru are semidiurnal with pronounced differences between spring and neap tides. At the city of Paita, the expected tidal amplitude at new moon spring tide is roughly 2 m, four times that expected for the following neap tide (about 0.5 m; Fig. 2). At full moon spring tide, the expected amplitude is only 1.5 m, and half of that value at the following neap tide (Fig. 2). The corresponding horizontal shifts of the water line on flat sandy beaches must be expected to differ by similar factors, which implies that the distances animals have to cover during their tidal migrations fluctuate significantly during the lunar cycle. It is unclear whether P. columellaris needs to migrate in order to enable suspension-feeding during neap tide phases at all. Here I report simple field studies that provide further insights into the biology and the surprisingly complex tidal migrations performed by P. columellaris on North-Peruvian sandy beaches.

Figure 2 Tide curve for the city of Paita, Peru, March 2014. The curve, based on numerical data in Anonymus (2013), is representative also for the study site at Colan, 11 km to the north. Blue circles indicate times of sampling at high and low tide on March 6, 7, 8, and 10 (results shown in Figs. 4, 5, 6, and 7, respectively). The time of observation of the ‘straggler zone’ (Fig. 8; retreating tide on March 8) is marked by a star, while that of the dense migration front used to estimate population size (Fig. 9; incoming tide on March 15) is highlighted by an orange square. Observations presented in Fig. 10A had been made in August 2013; the equivalent stages of the lunar tidal cycle are indicated in this graph by arrows above the tide curve.

Material and methods

A population of Pachyoliva columellaris was studied on a micro- to mesotidal beach at Colan, Peru (04°59′16″S, 081°04′28″W; geographic coordinates were determined using https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/), in August 2013 (cool season) and March 2014 (hot season).

To mark position 0 of a beach transect perpendicular to the water line, a stick (durable synthetic material; 1.2 m long, 6 mm diameter) was planted on the berm above the highest expected water line. The transect itself was defined by the sight line between this and a second marker planted at 15 m distance in the landward direction. While the markers that visually defined the transect line remained unchanged during the entire study period, additional markers were used before every sampling to mark the highest reach of the water during a 15-min period before sampling started, the upper and lower limits of the zone in which P. columellaris were suspension feeding, and the uppermost position that was submerged permanently during the same 15 min period. The exact position of each marker on the transect line was determined with a 100 m measuring tape after sampling was complete, and the markers in the intertidal were removed. Densities of P. columellaris along the transect line were determined at three different phases of the tidal cycle on each of four days in March 2014. Depending on the tidal phase, two to six positions along the transect line were sampled.

Sampling was conducted by pushing short rigid plastic tubes (28, 14, or 10 cm diameter, 20 cm length) into the sand. The sediment within the tubes was removed to 8 cm depth, sieved (1.5 mm mesh), and the retained P. columellaris were classified as small (<7 mm shell length), intermediate (7-10 mm), large (10-13 mm), or very large (>13 mm) and counted. Two to eight independent samples were taken at each position, and the animal densities of the samples taken were averaged to estimate animal density at that position.

Animal numbers per beach meter were estimated by geometric integration of the animal density profile along the beach transect (for an example, see Fig. 9D), assuming that the density dropped to 0 individuals per m2 at 1 m above the feeding zone on the landward side, and at the highest continuously submerged position on the seaward side of the transect.

Figures were prepared with SigmaPlot 11.0 (Systat Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) and Paint Shop Pro 6.00 (JASC Software Inc., Eden Prairie, MN, USA).

Results

Initial findings. Preliminary investigations into tidal migrations of P. columellaris on the study beach at Colan were conducted in August 2013 (cool season). At any phase of the tidal cycle, a band of densely accumulated, suspension-feeding P. columellaris was observable in the backwash zone, running for at least 40 km along the continuous sandy beach north of the study site (Olsson 1924, confirmed by own observations). Depending on tidal phase and steepness of the beach, this band had widths between 4 and 18 m measured along the beach slope. Determinations of animal densities in this feeding zone at high tide and at the same spots during the following low tide showed that the species performed tidal migrations (Peters et al. 2022). Observations on the beach evoked the impression that smaller specimens dominated in the upper and larger ones in the lower part of the feeding zone. The same site was visited again in March (hot season) of the following year to obtain more detailed insights into the tidal migrations of P. columellaris and its size distribution along the beach slope.

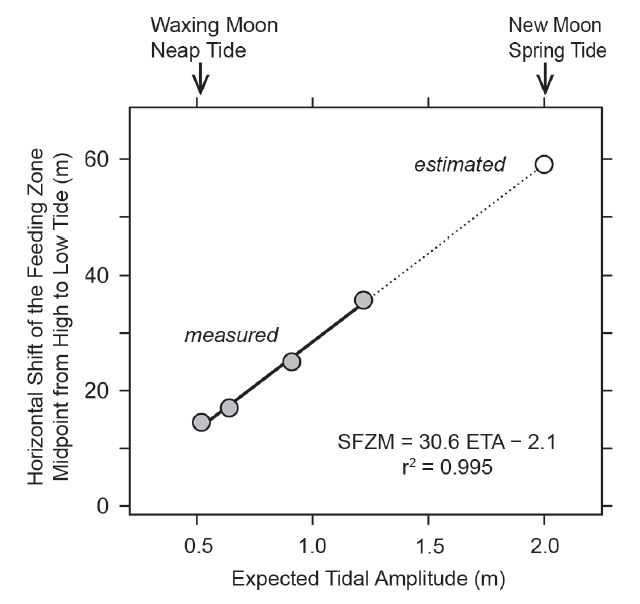

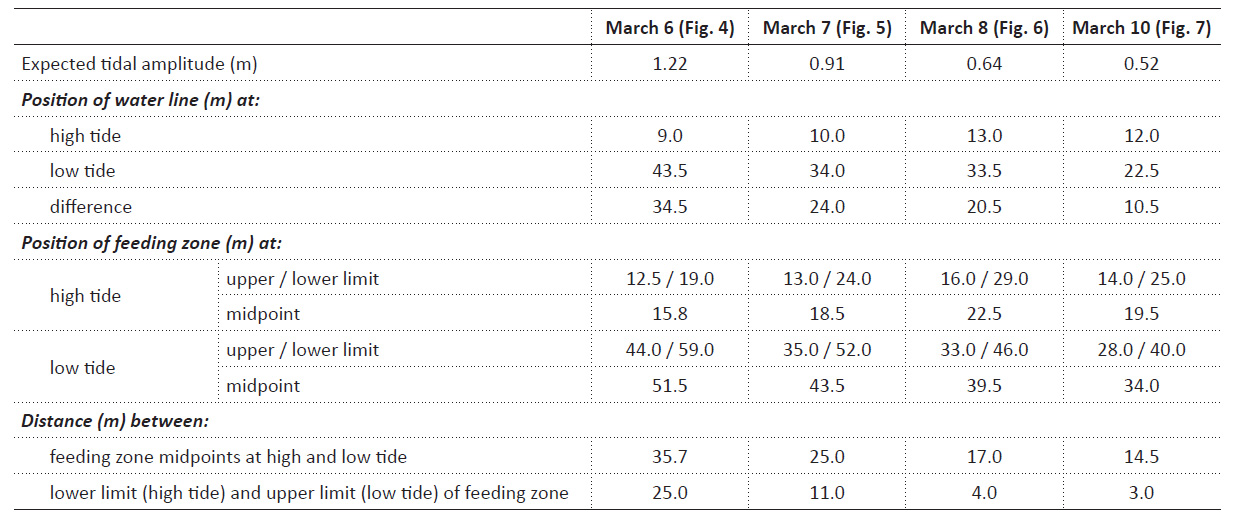

Tidal characteristics and movements of the feeding zone. In order to see whether tidal migrations occur at neap tide as they do at other phases of the lunar cycle, dates for additional studies at Colan were selected to include the smallest tidal amplitude (neap tide following new moon; Fig. 2). From March 6 to 10, the theoretically expected tidal amplitude decreased from 1.22 m to 0.52 m (Table 1). The corresponding horizontal movement of the water line between high and low tide actually observed on site decreased from 34.5 m to 10.5 m (Table 1). The zone in which P. columellaris were suspension-feeding was determined at high and the following low tides on the same days (Table 1; compare the transects sketched in Figs. 4-7 below). The magnitude of the tidal movement of the feeding zone can be expressed as the distance between the feeding zone midpoints at high and low tide. This distance, which decreased from 35.7 m on March 6 to 14.5 m on March 10 (Table 1), correlated linearly with predicted tidal amplitude (Fig. 3). Based on this relationship, the shift of the feeding zone midpoint at new moon spring tide, which had occurred on March 2 (Fig. 2) but had not been determined on site, could be tentatively estimated to be about 60 m (Fig. 3). Consequently, the average horizontal distance that P. columellaris has to travel at this site to remain in the feeding zone during an entire tidal cycle changes roughly four-fold between the lunar phases of maximum and minimum tidal amplitude (new moon spring tide and waxing moon neap tide, respectively).

Figure 3 Correlation between the horizontal shift of the feeding zone midpoint (SFZM) from high to low tide and the expected tidal amplitude (ETA) as observed at the study site (gray circles). The horizontal shift under new moon spring tide conditions (open circle) was estimated based on the observed correlation.

On the other hand, a minimum travel distance required for the animals to always remain in the feeding zone can be defined as the distance between the lower margin of the feeding zone at high tide and its upper margin at low tide. This minimum distance decreased from 25 m on March 6 to an almost negligible 3 m on March 10 (Table 1).

Table 1 Theoretically expected tidal amplitude, and the actually observed positions of the water line and the feeding zone at high and low tide on March 6, 7, 8, and 10 (compare transects sketched in Figs. 4, 5, 6, and 7, respectively). Distances the animals had to cover to remain within the feeding zone are estimated, first, as the shifts of the midpoint of the feeding zone from high to low tide (average migration distance), and second, as the distances between the lower limit of the feeding zone at high tide and the upper limit of the feeding zone at low tide (minimum migration distance).

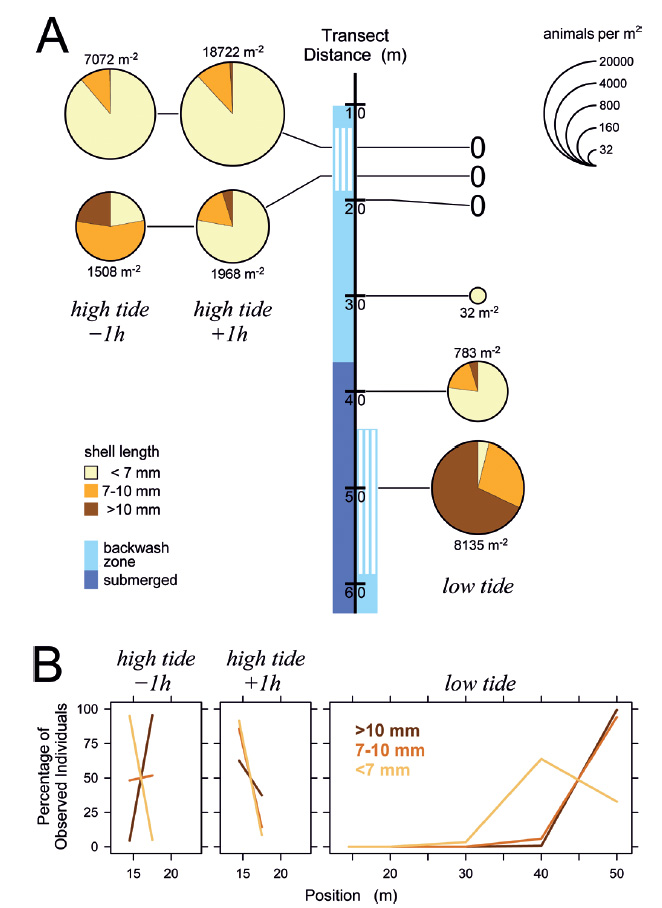

Tidal migrations and size gradients. To see whether the dominance of small individuals in the upper part of the feeding zone observed in August 2013 could be confirmed by quantitative data, samples were taken at 1 h before and 1 h after high tide, and again at low tide. The results for March 6, 2014 are plotted together with the positions of the water line and the feeding zone on the beach transect in Fig. 4A. Around high tide, smaller animals dominated in the upper but less so in the lower part of the feeding zone. At the same locations, no snails were found at low tide. At low tide, comparatively low densities of predominantly small snails were present a few meters above the feeding zone while intermediate and large animals were most abundant within the feeding zone (Fig. 4A). Intriguingly, the small animals that were found in drying sand at positions too high for feeding represented the majority of this size class found at low tide (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4 Distribution of Pachyoliva columellaris on the beach transect on March 6, 2014. (A) Animal densities 1 h before and after high tide (left) and at low tide (right), plotted at sampling location on the beach. Light blue along the transect marks the backwash zone with suspension-feeding gastropods indicated by white lines; dark blue marks continuously submerged zones (the situation was practically identical 1 h before and after high tide). Pie chart size represents animal density (legend at the upper right; 0 indicates lack of gastropods at a location), which is also given numerically next to each chart. Color-coded sectors in the charts show the proportions of small (<7 mm shell length), intermediate (7-10 mm), and large (>10 mm) individuals. Each pie chart presents the combined counts from ≥2 independent samples. (B) Distribution of animals of each size class given as percentages of each class found at the sampled positions.

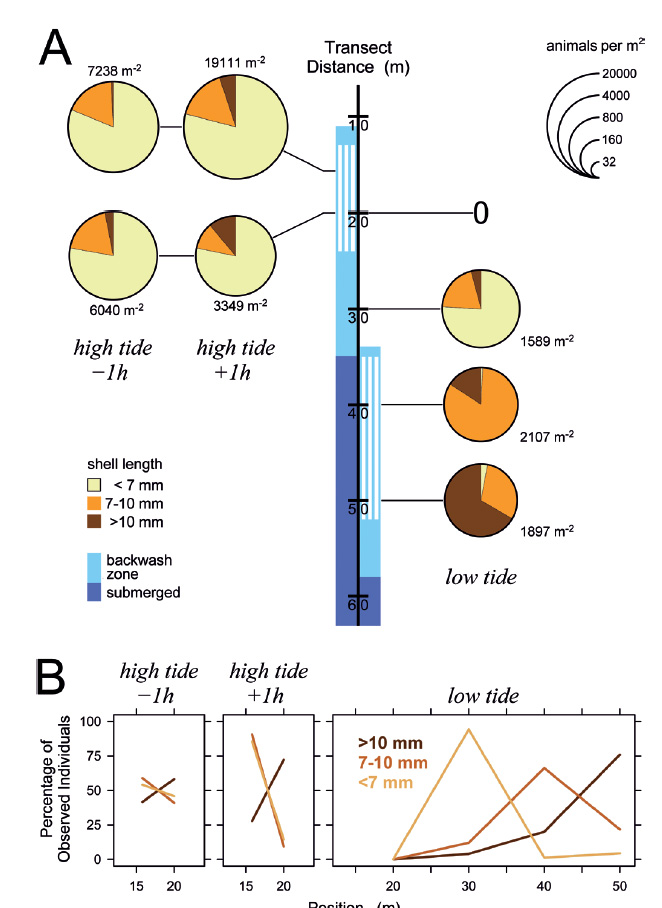

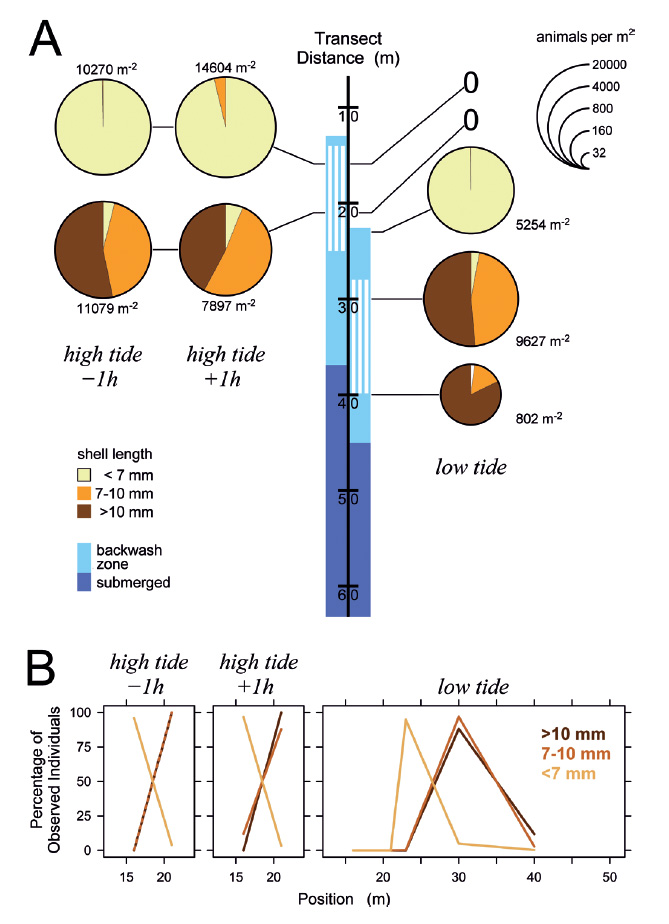

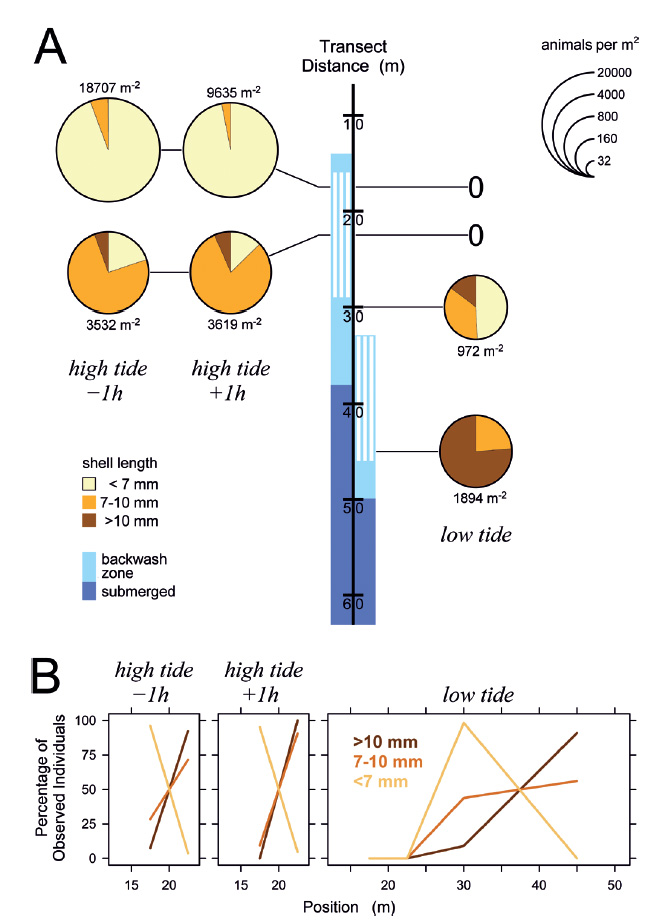

The situation remained similar when the tidal amplitude decreased in the following days (Figs. 5-7). Even at minimum tidal amplitude on March 10, the gastropods had completely disappeared at low tide from locations that had been occupied by the upper part of the feeding zone at high tide (Fig. 7A). Evidently, tidal migration occurred. Small animals dominated in the upper part of the feeding zone around high tide on all days (Figs. 5-7), with the proportions of intermediate and large animals in the lower part of the feeding zone increasing toward neap tide on March 10 (Fig. 7). At low tide, intermediate and large snails always dominated in the feeding zone, while the majority of small specimens generally was found above or at the water line. These small animals conducted tidal migrations but apparently did not follow the retreating tide to its lowest position, and consequently could not perform suspension feeding during a certain period around low tide. At low tide on March 8, animals that had ceased to migrate halfway through the ebb phase formed a conspicuous ‘straggler zone’ a few meter above the water line (Fig. 8). Presumably because the sediment was falling dry more quickly than usual at that position, numerous animals failed to burrow and remained in a more or less upright pose on the surface (Fig. 8c). I had observed but not analyzed similar ‘straggler zones’ in August 2013.

Figure 5 Distribution of Pachyoliva columellaris on March 7, 2014, along the beach transect. (A) Animal densities 1 h before and after high tide (left) and at low tide (right). See Fig. 4 for details. (B) Percentages of the total of each size class that were found at the sampled positions.

Figure 6 Distribution of Pachyoliva columellaris on March 8, 2014, along the beach transect. (A) Animal densities 1 h before and after high tide (left) and at low tide (right). See Fig. 4 for details. (B) Percentages of the total of each size class that were found at the sampled positions.

Figure 7 Distribution of Pachyoliva columellaris along the beach transect under waxing moon neap tide conditions on March 10, 2014. (A) Animal densities 1 h before and after high tide (left) and at low tide (right). See Fig. 4 for details. (B) Percentages of the total of each size class that were found at the sampled positions.

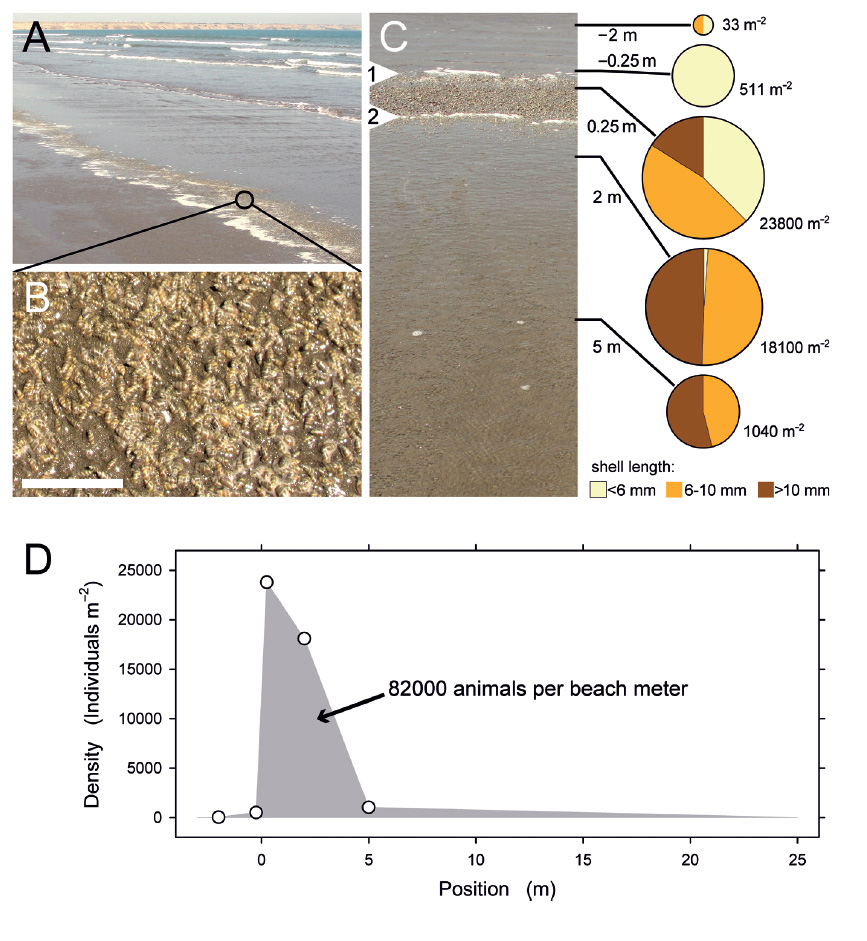

Dense accumulations and estimated population size. A very dense accumulation of P. columellaris developed during incoming tide on March 15, 2014, under conditions that allowed for an estimate of total population size. Several waves had reached almost exactly the same position on the beach slope over a period of 35 min, concentrating vast numbers of animals in a narrow zone underneath that waterline (Fig. 9A, B). Local densities were determined in a transect across the accumulation zone (Fig. 9C) before a large incoming wave reached over and dissipated the accumulation. The five transect stations tested indicated a size gradient as observed before, with smaller animals concentrated in the upper and larger ones in the lower part of the transect (Fig. 9C). Assuming that the density decreased to 0 at 1 m above the highest measuring station (equivalent to position −3 m in Fig. 9D) and also at the highest point that was constantly submerged at this stage (position 25 m in Fig. 9D), the total number of animals in a transect 1 m wide could be estimated by geometric integration to be about 82,000, or 8.2 × 107 per km of beach (Fig. 9D). This figure probably underestimates the real number because individuals that might have been present in the submerged part of the beach were not counted.

Figure 8 ‘Straggler zone’ at retreating tide on March 8, 2014. (A) Conspicuous accumulation of Pachyoliva columellaris at the transition between wet sand (shiny appearance due to light reflection) and the drier, upper beach. This accumulation zone appears rough (B) since the snails have not burrowed into the sediment as they normally do when resting, but rather assumed an upright position with their shell apices in the air (C). The straggler zone as seen in (B) corresponds to position 28−33 m on the beach transect in Fig. 6A (low tide), and the zone’s animal density and size composition is reflected in that figure by the samples taken at position 30 m.

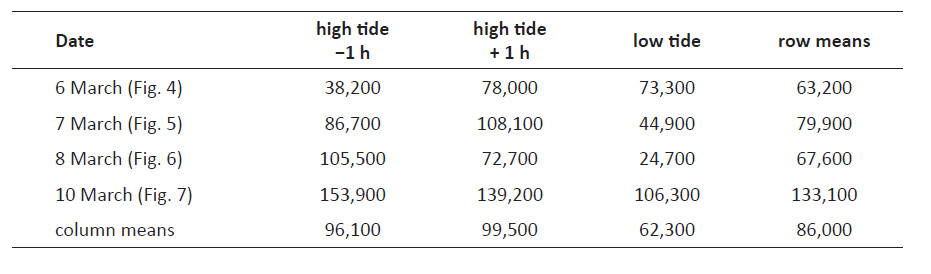

Analogous population size estimates based on the transects shown in Figs. 4-7 were expected to be less reliable because these transects had only two or three stations at which animals had been counted. However, rough estimates could be produced assuming that densities decrease to 0 at 1 m above the feeding zone and also at the highest position that was continuously submerged. The resulting twelve estimates varied significantly (from 38,200 to 153,900) but averaged at 86,000 (Table 2), well in line with the estimate of 82,000 derived from the event of March 15 (Fig. 9).

Table 2 Estimates of the total numbers of Pachyoliva columellaris per beach meter (i.e., in a transect of 1 m width along the beach slope), calculated by geometric integration of the animal counts of the transects presented in Figs. 4-7.

Figure 9 Extreme density of Pachyoliva columellaris at the migration front at incoming tide (March 15, 2014). (A) Conspicuous accumulation of animals below the highest reach of waves so far in this tidal phase. (B) Animals literally are lying on each other in this zone. Scale bar: 5 cm. (C) The accumulation viewed from seaward. Foam lines indicate the reach of the most advanced swash in this cycle (marker 1 on the left) as well as that of the most recent swash (marker 2). In the backwash between foam line 2 and the camera position, large numbers of animals are suspension-feeding; smaller numbers were observed down to position 25 m. Pie charts show total densities (individuals m−2) and size distributions (small, <6 mm shell length; intermediate, 6−10 mm; large, >10 mm) determined in three samples each taken at the positions indicated relative to marker 1; positive values are distances in the seaward direction. (D) Density profile and estimation of the total number of animals per beach meter.

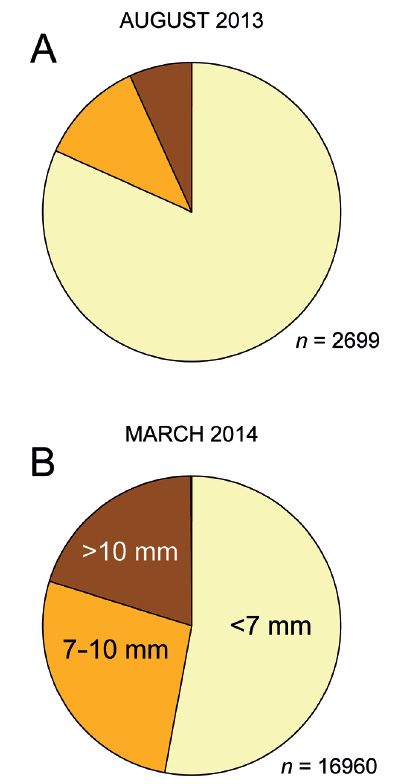

Body size spectrum of the population. In August 2013 (cool season), a total of 2,699 individuals had been counted in sediment samples collected for the determination of animal densities in the feeding zone at mid ebb tide, and were assigned to body size classes according to shell length as defined in the Material-and-methods section (small, <7 mm; intermediate, 7-10 mm; large, 10-13 mm). Unsurprisingly, smaller and therefore younger specimens were more common. Small individuals contributed 81.7% (2,206), intermediate ones 11.5% (310), and large ones 6.8% (183) of the observed population (Fig. 10A). Very large animals (>13 mm shell length) were absent from the samples but evidently did occur at this site, as numerous empty shells of up to 15 mm length were found in the berm above the intertidal zone.

The body size distribution had shifted notably to the larger size classes in March 2014 (hot season). Of the 16,960 snails counted, just over half (8,974; 52.9%) were small, one quarter (4,560; 26.9%) were intermediate, one fifth (3,406; 20.1%) were large, and a few (20; 0.1%) were very large (Fig. 10B; the samples presented in Fig. 9 that for technical reasons had been analyzed using a small/intermediate border of 6 rather than 7 mm are not included in these overall counts). Thus, compared to August 2013, the proportion of small animals had declined by one third while that of intermediate plus large and very large animals had more than doubled.

Figure 10 Overall size distribution of the Pachyoliva columellaris samples analyzed in August 2013 (A) and March 2014 (B). Pie charts show the proportions of small (<7 mm shell length), intermediate (7−10 mm), and large (10−13 mm) specimens. The proportions of very large animals (>13 mm) were too small to show in these charts.

Discussion

Inhabitants of tidal zones have to tolerate a constantly changing physical environment. Not only does the water level oscillate with a diurnal to semi-diurnal rhythm, but the amplitudes of these oscillations change significantly during the lunar cycle on most coasts (Bowers & Rogers 2019). At the study site near Paita, Peru, maximum and minimum tidal amplitudes differ four-fold (Fig. 2, Table 1). Comparing new moon spring tide and neap tide, this translates into an also about four-fold difference of the horizontal distances between the midpoints of the zones in which P. columellaris feed at high and low water (Fig. 3). Assuming that tidal migrations proceed homogeneously over a 6-hour period between high and low water, migrating animals will have to move at average velocities of about 16.7 cm min-1 at new moon spring tide but only of 4.2 cm min-1 at the following, waxing moon neap tide. For full moon spring tide and the following waning moon neap tide, the estimated average velocities are 12.8 cm min-1 and 7.1 cm min-1, respectively. How such complex migratory behavior could be regulated by an endogenous circatidal clock (as suggested by Vanagt et al. 2008) is unclear, unless the output of that clock was modified by an endogenous circalunar clock that, in addition to distinguishing spring and neap tides, would have to enable the differentiation between waning and waxing moon phases. Additional complications may be caused by irradiation levels, which obviously differ between day and night and also between the hot and the cool season. Maximum irradiation intensities around noon correspond to different phases of the tidal cycle every day, as the times of high and low tide slowly shift around the clock from day to day. Irradiation levels define the degree of heat and desiccation stress to which P. columellaris may be exposed on the upper beach, and potential predators that depend on visual prey detection forage only during daylight hours. It is obscure how endogenous circatidal clocks could help P. columellaris to respond appropriately to these variable factors. Based on currently available information, the conclusion that tidal migrations of sandy beach gastropods are direct responses to momentary environmental conditions appears more plausible (McLachlan et al. 1979, Brown 1996, Morse & Peters 2016).

At the studied site, P. columellaris performed tidal migrations even at waxing moon neap tide, when the location of its feeding zone at high water did not fall dry entirely at low water (Fig. 7). However, the animals did not all migrate in perfect agreement with the movement of the water line. At times of low water, there always were significant densities of gastropods above the water line (Fig. 4-7), sometimes forming conspicuous ‘straggler zones’ (Fig. 8). These ‘stragglers’ had not completed the downward migration with the retreating water and lay dry, so to speak, until the water’s return with the next incoming tide. The phenomenon may simply reflect behavioral shortcomings like a failure to initiate underwater sailing locomotion in time. Alternative causes cannot be excluded, though. It seems possible, for example, that well-fed individuals migrate with the ebb tide not so much to remain in the feeding zone, but to avoid prolonged exposure to unfavorable temperatures and the dryness of the upper beach. These animals might save energy by terminating their seaward movement before they reach the low tide water line, at locations that remain dry for short periods only.

With one possible exception (high tide on March 07; Fig. 5), a body size gradient along the beach slope was clearly evident at all times. Small P. columellaris dominated close to or above the water line while the proportions of intermediate and large individuals increased in the seaward direction (Figs. 4-7, 9). There are two obvious but not necessarily alternative, hypothetical explanations, a behavioral and a biomechanical one. First, the snails may modify their migration behavior as they grow to maturity, actively searching for different water depths, flow velocities, backwash durations, etc., at different ages. Second, the size gradients may be simple biomechanical effects of body size. The efficiency of sailing locomotion increases with the hydraulic resistance offered to the moving fluid but decreases with the mass of the sailing object. Body volume and thus body mass are proportional to body length raised to the third power. On the other hand, hydraulic resistance depends on body surface area, which is proportional to body length raised to the second power (Schmidt-Nielsen 1984). Consequently, the ratio of body mass to hydraulic resistance most certainly increases with increasing body length. Therefore the hydrodynamic properties of the gastropods change as they grow. This may cause size-dependent differences in the distribution of the constantly migrating P. columellaris on the beach, even if individuals of all sizes behave in the same way.

Benthic suspension feeders establish benthic-pelagic trophic coupling, which is important especially in littoral food webs (Gili & Coma 1998). To evaluate the ecological function of a suspension feeder in a specific region, quantitative data on feeding rates and population density are required. While information on feeding rates of P. columellaris is unavailable at this time, the samples analyzed here allowed to estimate the number of specimens per beach meter to be in the range of 80,000 to 90,000 (Fig. 9, Table 2). The study site is located at the Southern end of a continuous stretch of 44 km of sandy beach between Colan (04°59′28″S, 081°04′22″W) and Punta Balcones (04°40′58″S, 081°19′40″W), interrupted only by the mouth of the Rio Chira (04°53′54″S, 081°08′52″W). Assuming an average count of 85,000 animals per beach meter, the estimated population size in this region is 3.7 × 109 specimens. I emphasize that this is a minimum estimate because my counts did not include, first, the portion of the population in the subtidal zone, and second, individuals of under 1.5 mm shell length, which were not retained when the sediment samples were sieved for analysis. Nonetheless, the estimate supports the conclusion that the suspension-feeding P. columellaris is a significant factor in the trophic network of the near-shore marine ecosystem in this region.

It is obvious that the body size composition in the samples I took depended, first, on the position on the transect and, second, on the phase of the tidal cycle (Figs. 4-7). As the samples taken did not cover the entire habitat including the subtidal zone, they may not represent the body size composition of the entire population. As a consequence, any conclusions concerning the body size spectrum of the population as a whole and its seasonal changes will be tentative and have to be evaluated carefully. Nonetheless, the data suggests an interesting trend. In the hot season (March 2014), the proportion of large and very large individuals combined had increased by 13.4 percentage points compared to the cool season (August 2013; Fig. 10). This proportional increase was greater than the proportion of intermediate animals in August 2013 (11.5%). Therefore, if this data is representative, some of the individuals that qualified as large or very large in March 2014 must have been part of the cohort of small specimens in August 2013. This observation hints at individual growth rates that seem substantial enough to cause seasonal changes in the size spectrum of the population. The significant drop in the proportion of small individuals from August to March indicates that any recruitment of juveniles to the population that may have occurred in this period was insufficient to balance the growth-dependent transfer of small animals to larger size classes. I infer that juvenile recruitment probably takes place predominantly between March and August, and that P. columellaris reproduces mostly in the late hot and/or the early cool season.

The present work expands our knowledge of P. columellaris, a dominant species on many sandy beaches in north Peru, and demonstrates in particular that the circatidal migratory behavior of these gastropods is more complex than previously assumed. As discussed above, the field observations reported in this paper suggest specific hypotheses concerning (i) the regulation of tidal migrations (by momentary conditions, not by endogenous clocks), (ii) the incompleteness of tidal migrations leading to accumulations of ‘stragglers’ (which may migrate for reasons unrelated to feeding), (iii) the mechanisms (biomechanic versus behavioral) behind the development of body size gradients along the beach slope, and (iv) the life cycle of P. columellaris (rapid growth; reproduction mainly in the late hot or early cool season). The region between Paita and Punta Balcones appears particularly well-suited to test these and other hypotheses concerning the ecology and general biology of P. columellaris in more detailed field studies. Such studies promise to expand our understanding of the sensory, behavioral, and biomechanic mechanisms that underlie invertebrate tidal migrations in general.

uBio

uBio