INTRODUCTION

The páramo is a distinctive ecosystem of the northern high-tropical Andes (Neill 1999, Jiménez-Rivillas et al. 2018). Located above the high-montane Andean Forest treeline, the páramo harbours important endemic, restricted-range bird species, and a high concentration of threatened species (Stattersfield et al. 1998, Mena-Vásconez & Hofstede 2006, Jiménez-Rivillas et al. 2018). The influence of local environmental variation and climatic conditions over the páramo gives rise to several habitat types with distinct characteristics, such as tussock grasses, ground rosettes, cushion páramo, woody shrubs, or Polylepis woodlands (Sklenár & Ramsay 2001, García et al. 2020), which in turn lead to processes of habitat adaptation and specialization in páramo birds (Norambuena & Van Els 2021). Combined, these páramo habitats harbour the important bird diversity across the region.

In Ecuador, the Macizo del Cajas biosphere reserve (MCB) is located in southern Ecuador and the páramos within the reserve are considered a particular district forming part of the biogeographic province of the northern Andes, with relevance in terms of diversity and endemism (Jiménez-Rivillas et al. 2018). However, páramo areas are not exempt from current impacts of anthropogenic activities including the expansion of the agricultural frontier, fires to promote pastures, introduction of exotic species, impacts of road infrastructure, illegal resource extraction, and climate change (Sarmiento 2000, Matson & Bart 2013, Báez et al. 2016, Aguilar et al. 2019, Carrillo-Rojas et al. 2019). An additional factor is the potential negative effects of mining activities; in particular, uncontrolled and unlawful activities which could promote habitat loss. Two protected areas in the páramo landscape of the MCB, Cajas National Park and Quimsacocha National Recreation Area, form part of the national park system and the core of the MCB and, are vital for the conservation of bird species and their associated habitats in the region (Barros et al. 2020a). Like many other priority conservation territories, beyond the limits of the protected areas inside of MCB, functional landscapes and habitats necessary to maintain ecological processes and species with the widest distribution ranges may not be fully protected (Cuesta et al. 2017).

Species inventories are an important conservation tool; in particular, information about bird diversity in conservation hotspots, such as the MCB, is crucial to improve strategies and achieve compatible regional conservation efforts (Myers et al. 2000, Lees et al. 2020, Soares et al. 2023). A checklist of bird diversity in Cajas National Park exists, but it does not include a large portion of MCB (Astudillo et al. 2015). Throughout the MCB páramo landscape, birdwatching has resulted in an important number of records on online databases, especially eBird and GBIF. Furthermore, the Universidad del Azuay conducts continuous bird monitoring in several páramo areas of the MCB and maintains an up-to-date database as well as has produced several publications (e.g., Tinoco et al. 2013; Astudillo et al. 2018; Barros et al 2023). For instance, recent studies within the páramo landscape of MCB have examined important aspects to understanding diversity and distribution, including bird occurrences in specific localities (inside or outside of Ecuadorian system of protected areas) (e.g., Barros et al. 2020b, Villegas et al. 2022), and species-specific responses to habitat change (e.g., Tinoco et al. 2009, Astudillo et al. 2016, Molina-Abril et al. 2019, Carrasco-Ugalde et al. 2022). These studies contribute a more integrated perspective to a comprehensive inventory of bird diversity for the entire páramo of MCB. Within this framework, information about habitat associations, such as species affinities to different páramo habitats, facilitates understanding of how birds respond to habitat loss related to land-use and climate change (e.g., Brauning 2001, Astudillo et al. 2018, 2020, Barros et al. 2020a).

As no updated checklists for this important páramo region exist, here we compile observations from different sources (i.e., monitoring efforts and free access online database) and present an extensive, annotated checklist of the birds of the páramo in a conservation hotspot, the MCB. Our checklist includes information on habitat affinity of bird species, status, and relative abundance. We provide additional details about the status of particularly rare birds of conservation concern.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

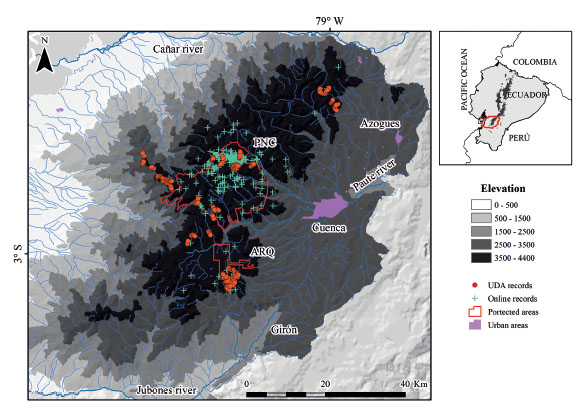

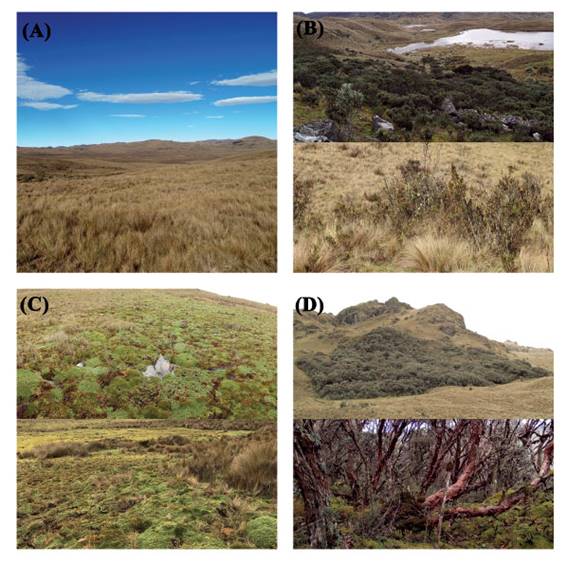

Study area. The MCB is located within the provinces of Azuay and Cañar in the Western-Andean cordillera of southern Ecuador (2°55’25’’S, 79°21’57’’W). The MCB is bounded in the north by the Cañar River and to the south by the Jubones River (Fig. 1). This study was carried out in the páramo ecosystem across the High-Andes of MCB (> 3500 m a.s.l.) (Fig. 1). The páramos of the study area are considered a particular biogeographic district within the páramo biogeographic province of northern Andes (Jiménez-Rivillas et al. 2018). The páramo is one of several types of ecosystems occurring in the MCB and it covers ~16% of their surface (total area of MCB = 976601 ha; total area of páramo = 169631 ha). Within the páramo landscape, six distinct habitat types can be distinguished as important for birds (Fig. 2) (e.g., Astudillo et al. 2019, 2020, Barros et al. 2020a, 2023): (i) páramo grassland (Fig. 2A), a widespread open habitat mainly characterized by native tussock-grasses from the genus Calamagrostis (Poaceae); (ii) shrubby páramo (Fig. 2B), a semi-open habitat with woody plants species from Chuquiraga, Diplostephium, Loricaria (Asteraceae), Brachyotum and Miconia (Melastomataceae); (iii) cushion páramo (Fig. 2C), open habitat but in more humid areas dominated by cushion plants such as Plantago rigida (Plantaginaceae) and Oreobolus ecuadorensis (Cyperaceae); (iv) Polylepis forest (Fig. 2D), patchy distributed woodland mainly dominated by two species, P. reticulata and P. incana (Rosaceae); (v) water bodies and aquatic habitats, including lakes, streams, and small rivers, as well as marshes; and finally, (vi) Andean montane forest edge, a transitional lower páramo habitat influenced by the upper limit of montane cloud forest. The two protected areas, Cajas National Park (PNC; 2°50’45’’S, 79°14’33’’W) and Quimsacocha National Recreation Area (ARQ; 3°00’45’’ S, 79°14’12’’ W), form the core of the MCB (Fig. 1) and are dominated by páramo vegetation (~ 90%) covering 31761 ha (Barros et al. 2020a). Average monthly temperatures in the region vary from 5 - 12 °C, while the average annual precipitation ranges from 1200 - 1500 mm (Celleri et al. 2007, Campozano et al. 2016). Typically, two rainy seasons occur annually; the first between March and April, and a second, less intense season, between September and February. The lowest precipitation occurs between June and August (Celleri et al. 2007, Campozano et al. 2018).

Figure 1 Map of the study area and location of records in the páramo ecosystem of the Macizo del Cajas Biosphere Reserve (MCB), High-Andes of southern Ecuador. The information from laboratory of ecology, Universidad del Azuay are 7893 observations and those from online information (eBird 2023, GBIF 2023) are 12715 observations. The protected areas, PNC = Cajas National Park and ARQ = Quimsacocha National Recreation Area.

Figure 2 Important habitats for páramo birds of the Macizo del Cajas Biosphere Reserve (MCB). In A, páramo grassland; B, semi open shrubby páramo (upper panel) and more open shrubby páramo (lower panel); C, cushion páramo and; D, Polylepis woodland (upper panel) and the interior woodland (lower panel).

Bird data. We collected bird occurrence data from three main sources. First, we included all the records documented from 1939 to 2022 and reported in the eBird database (eBird 2023) or GBIF database (GBIF 2023) (cut-off date of 13 January 2023). As these databases are synchronized, we avoided duplicate information by checking the metadata of sources (e.g., GBIF contained columns which inform about platform the record came from). All records were carefully curated to avoid taxonomic and distributional inconsistencies in accordance with Fjeldså & Krabbe (1990), Ridgely & Greenfield (2001), Astudillo et al. (2015), Freile & Restall (2018), and Barros et al. (2020a, 2023). Rare and unusual records in eBird and GBIF were only included if the occurrence was accompanied by photographic (e.g., Fig. 3) or video evidence and a description of the habitat where the record was made. Any occurrence that exhibited notable inconsistencies was excluded. Second, we included records of birds gleaned from scientific publications (n = 15) related to the study area. Finally, we accessed the database containing observations from five years of monitoring páramo birds in the southern Andes of Ecuador maintained by the laboratory of ecology at the Universidad del Azuay. This database contains observations of birds recorded across 106 transects in various locations (Table 1) that were monitored at least once a month between 2016 and 2021, following the monitoring protocol developed for the study region (Astudillo et al. 2018, Barros et al. 2020a). Here, the transect method was chosen for its effectiveness for counting birds in open habitats (Ralph et al. 1996). Each transect was 1 km long and separated by at least 350 m, which were monitored by walking at a constant pace (~ 1 km h-1) while recording all birds seen and heard within 50 m either side of the transect. We present records following the South American Classification Committee taxonomy (SACC; Remsen et al. 2023). Determination of the threatened status of species follows the red list of the birds of Ecuador (Freile et al. 2019), as well as the IUCN red list (IUCN 2022). Endemism is based on Stattersfield et al. (1998), and habitat affinities are derived from habitat descriptions of birds by Ridgely & Greenfield (2001), Freile & Restall (2018), Astudillo et al. (2015), Barros et al. (2020a), and our field observations. We used four relative abundance categories established by Astudillo et al. (2015). These include: (i) very common; large numbers present in suitable habitat, (ii) common; easy to observe in smaller numbers in suitable habitat, (iii) fairly common; infrequently recorded in suitable habitat, and (iv) rare; difficult to observe in suitable habitat, with few records in the study area.

Figure 3 Examples of páramo birds recorded in the Macizo del Cajas Biosphere Reserve (MCB), High-Andes of southern Ecuador. In A, Tit-like Dacnis (Xenodacnis parina), adult female at upper panel and adult male lower panel; B, Stout-billed Cinclodes (Cinclodes excelsior); C, Violet-throated Metaltail (Metallura baroni) and D, Andean Condor (Vultur gryphus), a wing-banded adult female (named Chunka by Fundación Cóndor in Ecuador) at upper panel (photo by R. Jiménez) and adult male at lower panel.

RESULTDS

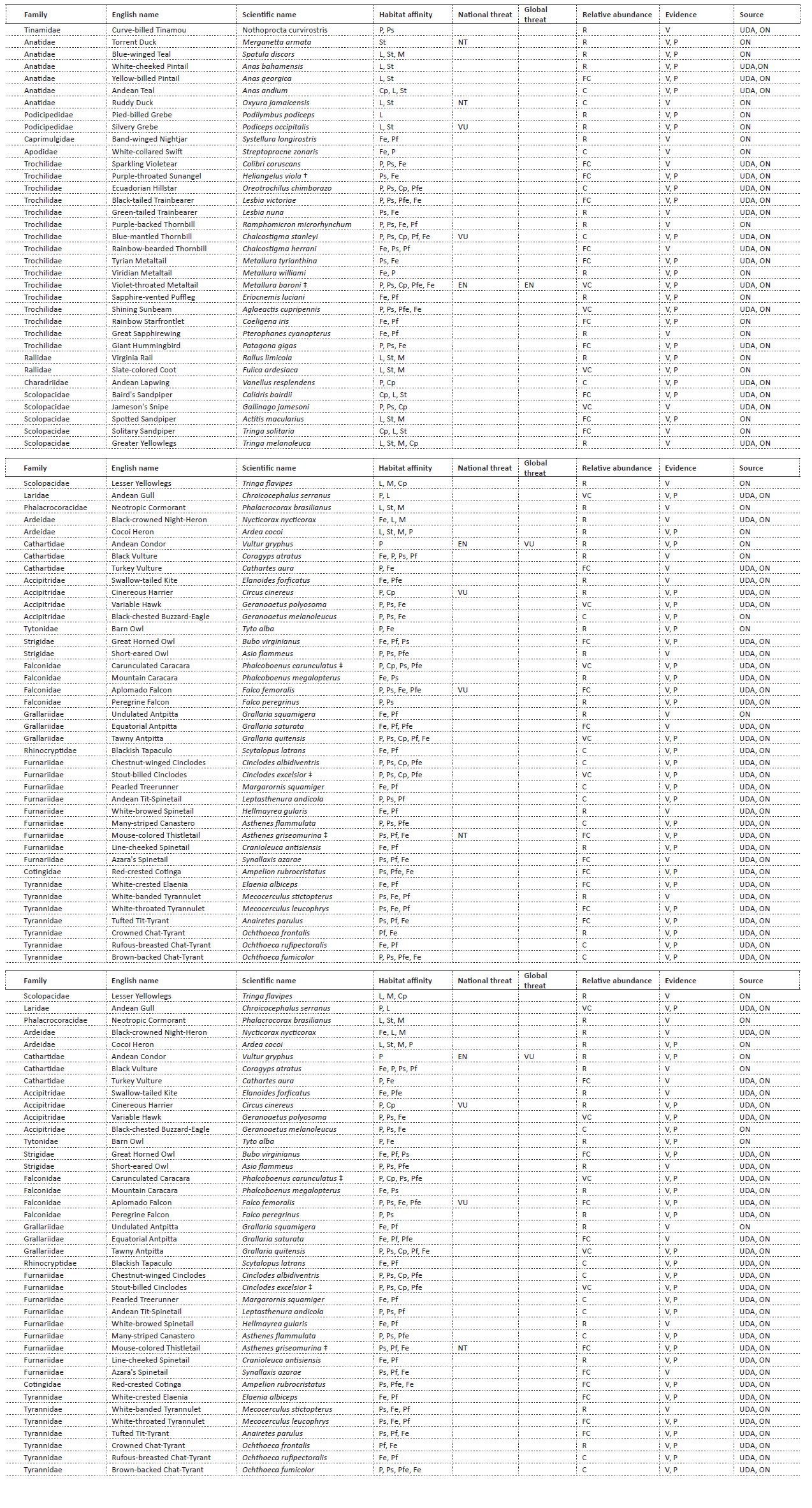

We collected data on a total of 112 bird species, grouped into 14 orders and 32 families (Table 2). Families with the highest number of species were Thraupidae and Trochilidae, each represented by 16 species (14%), and Tyrannidae with 12 species (11%). Thirteen families were represented by only one species. Globally threatened birds were represented by three species (3%), while 12 (10%) species were considered to be nationally threatened. Five species (4%) were endemic. In terms of relative abundance, species with categories of very common (n = 13) accounted for 12%, common species (n = 19) made up 17%, while fairly common (n = 42) and rare species (n = 38) comprised 38% and 34% of species listed, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2 Checklist of the páramo birds of the Macizo del Cajas Biosphere Reserve, High-Andes of southern Ecuador (> 3500 m a.s.l.). In symbols associated with scientific names, endemism (Stattersfield et al. 1998): † = Southern Central Andes, ‡ = Central Andean Páramo. In columns, national threat (Freile et al. 2019) and global threat (IUCN 2022): CR = Critically Endangered, EN = Endangered, NT = Near threatened, VU = Vulnerable. Habitat affinity (Astudillo et al. 2015, Barros et al. 2020 and pers. obs.): Cp = Cushion páramo, Fe = Forest edge, L = Lake, M = Marshes, P = Páramo grassland, Ps = Shrubby páramo, Pf = Polylepis forest, Pfe = Polylepis forest edge, St = Streams. Relative abundance (Astudillo et al. 2015 and pers. obs.): R= Rare, FC = Fairly Common, C = Common, VC = Very common. Evidence: V = Visual record only, P = Photograph record. Source: UDA = Database of Laboratory of ecology, Universidad del Azuay, ON = Online data base (eBird 2023, GBIF 2023). Taxonomy follows the South American Classification Committee (Remsen et al. 2023).

The most common species observed in the MCB (> 50% of the cumulative observations) included, Many-striped Canastero Asthenes flammulata, Grass Wren Cistothorus platensis, Plumbeous Sierra Finch Geospizopsis unicolor, Tawny Antpitta Grallaria quitensis, and Brown-backed Chat-Tyrant Ochthoeca fumicolor. Among the local endemic species, we recorded Purple-throated Sunangel Heliangelus viola for the South-Central Andes endemic region, and the Violet-throated Metaltail Metallura baroni (Fig. 3C), Carunculated Caracara Phalcoboenus carunculatus, Stout-billed Cinclodes Cinclodes excelsior (Fig. 3B), and Mouse-colored Thistletail Asthenes griseomurina for the Central Andean endemic region. Finally, we also report several species with scarce records or as new for the study area (Table 2).

Finally, habitat affinity among the study area is heterogeneous (Table 2): 87 (78%) species occur in high-elevation Andean Forest edge, scrub, and Polylepis woodland; 43 (39%) of these also use open páramo grasslands as well as open cushion páramo. Moreover, 21 (19%) of species inhabit aquatic habitats, 12 (11%) of which are only found on lakes, marshes or streams.

ACCOUNTS OF NEW, RARE AND CONSERVATION CONCERN SPECIES

Curve-billed Tinamou Nothoprocta curvirostris. Uncommon and local in Ecuador at 3000-3900 m a.s.l. (Freile & Restall 2018). Habitat preference is poorly understood but is usually found from temperate zones to páramo, around areas of bunchgrasses with less cover of shrubs and bushes (Fjeldså & Krabbe 1990, Ridgely & Greenfield 2001, Freile & Restall 2018). Since 2012, six observations have been reported for the study area (eBird 2023, GBIF 2023). Several observations also exist outside the protected areas in localities such as Rircay, Canoas, Río Frío, and Galgal (Table 1). These records mainly correspond to páramo grassland and cushion páramo.

Pied-billed Grebe Podilymbus podiceps. Occurs locally in isolated lakes across the Andes of Ecuador (Ridgely & Greenfield 2001). Most commonly found in large lakes (Fjeldså & Krabbe 1990, Ridgely & Greenfield 2001, Freile & Restall 2018). Six observations have been reported for the study area since 1992 (eBird 2023, GBIF 2023). Most records are located within the PNC in Llaviucu and Osohuaycu Lakes (Table 1) (eBird 2023).

Violet-throated Metaltail Metallura baroni. Endemic to South-Central Andes and restricted to the south western High-Andes of Ecuador; considered globally and nationally endangered (BirdLife International 2016, Freile et al. 2019). Distributed between the Cañar and Jubones rivers above 3000 m a.s.l., with an estimated global range smaller than 2000 km2 (Tinoco et al. 2009). The protected areas within this range are PNC and ARQ. The highlands of MCB encompass the entire geographic range of the species. M. baroni is common above 3300 m a.s.l. In our monitoring program, individuals were recorded (e.g., Fig. 3C) in diverse habitats such as shrubby páramo, páramo grassland, cushion páramo, and Polylepis forest edge; including localities such as Angas, Burgay, Chacayacu, Galgal, Ishcayrrumi, Migüir, Rircay, Santa Ana, Taitachugo, Tarqui, and Tomebamba (Table 1). In eBird, 700 observations have been reported, with more than 62 observations with photographic or video evidence (eBird 2023, GBIF 2023). M. baroni can commonly be found feeding on species of Brachyotum (Melastomataceae), Berberis (Berberidaceae), and Barnadesia arborea (Asteraceae) (Tinoco et al. 2009, Astudillo et al. 2019, Barros et al. 2020a). Habitat loss is the main threat for this species (Tinoco et al. 2009). For example, road infrastructure negatively influences the structure and composition of suitable habitat, as well as increased road-kill through roadside nesting (Carrasco-Ugalde et al. 2022). This results in negative effects on abundance and survival patterns (Astudillo et al. 2014, Aguilar et al. 2019). While within the Ecuadorian system of protection areas M. baroni is under protection, we also note localities of interest outside protected areas that are of interest, such as Angas, Galgal, Migüir, Rircay, and Ishcayrrumi (Table 1).

Greater Yellowlegs Tringa melanoleuca. Inhabits a wide variety of habitats from tropical zones to páramo, from coastal lagoons to páramo rain pools, marshes, and rivers (Fjeldså & Krabbe 1990, Ridgely & Greenfield 2001, Freile & Restall 2018). While usually considered rare throughout the Andes, it may wander to nearly 4000 m a.s.l. (Fjeldså & Krabbe 1990). On 20 August 2012, six individuals were photographed in PNC at Toreadora Lake, and one at Illincocha Lake (Astudillo et al. 2015) on a shore dominated by cushion páramo. Five observations have been reported since 2009 (eBird 2023, GBIF 2023) at the aforementioned localities (Table 1).

Neotropic Cormorant Phalacrocorax brasilianus. Rare in the highlands of Ecuador, this species is widespread and locally common along open rivers, lakes, and lagoons in the western and eastern lowlands (Fjeldså & Krabbe 1990, Ridgely & Greenfield 2001, Freile & Restall 2018). In the study area the species is also rare. Few observations have been reported in the Southern Andes. On 9 November 2005, a juvenile was observed for 15 minutes on the shores of Llaviucu Lake (Astudillo et al. 2015), and two individuals were observed in the Osohuaycu Lake on 26 January 2014 (Table 1) in PNC (GBIF 2023). Records of this species from the study area are considered vagrants (Astudillo et al. 2015).

Cocoi Heron Ardea cocoi. Widely distributed along freshwater and saltwater bodies in the eastern and western lowlands, it is rare in the High-Andes of Ecuador (Ridgely & Greenfield 2001, Freile & Restall 2018). On 14 January 2016, one individual was photographed in PNC on the shores of Toreadora Lake (Table 1) (Juca 2016). This is the first and only record for MCB. Apparently, it was a vagrant individual.

Andean Condor Vultur gryphus. Rare in Ecuador, inhabits mostly barren open mountain areas, steep slopes, cliffs, and open páramo grassland (Fjeldså & Krabbe 1990, Ridgely & Greenfield 2001, Freile & Restall 2018). Considered vulnerable globally (BirdLife International 2020), in Ecuador this species is classified endangered (Freile et al. 2019). Populations in the south are much smaller than those in the north (Astudillo et al. 2016, Naveda-Rodríguez et al. 2016). In 2003, 10 individuals were observed in PNC feeding on carrion (Astudillo et al. 2015), and six were at feeding stations in 2011 (Astudillo et al. 2011). On eBird, 58 observations are reported with eight photographic records (eBird 2023, GBIF 2023). More recently, 14 new observations have been made during the páramo bird monitoring program since 19 October 2020 (Fig. 3D) (Barros et al. 2023); eight individuals within the boundaries of ARQ and six individuals in Chumblin (Table 1). In addition, two new camera-trap observations of individuals feeding on carrion came from Sombrereras and Quinahuayco (Table 1). In Sombreresas, an adult female on 27 November 2021 (J. Fernández de Córdova, unpubl. data.), and also a banded adult female (code = 10) (R. Jiménez, unpubl. data) in Quinahuayco (Fig. 3D). This last individual is named Chunka and is satellite-monitored by Fundación Cóndor in Ecuador. These reports demonstrate that páramos outside of protected areas in MCB are important of feeding resources for species.

Cinereous Harrier Circus cinereus. Rare and local in the north, it also occurs to the south-central Andes of Ecuador (Freile & Restall 2018). Inhabits open marshes, agricultural grasslands, and páramo (Fjeldså & Krabbe 1990, Ridgely & Greenfield 2001, Freile & Restall 2018). Little is known about its distribution in the southern High-Andes of Ecuador, with few observations in this region. Two records have recently been reported (Villegas et al. 2022): on 21 October 2020, an adult female was filmed perching at ground level in cushion páramo at ARQ, and on 1 December 2020 an adult male was observed in flight outside the limits of ARQ (Villegas et al. 2022).

Mountain Caracara Phalcoboenus megalopterus. In Ecuador, the specie is mainly distributed in southern Andes (Fjeldså & Krabbe 1990, Ridgely & Greenfield 2001, Freile & Restall 2018). Inhabits open páramo grassland, grazed areas, ploughed lands, and shoreline meadows of lakes (Ridgely & Greenfield 2001, Freile & Restall 2018). In the study area, the first photographic documentation was on 30 August 2018 in San Gerardo (Barros et al. 2020b) in a mosaic of farmlands surrounded by páramo grassland. Three more recent observations have been reported;1 August 2020 at Quinoas Lake (Matamoros 2020), 29 January 2022 at Soldados (Normand 2022), and 2 April 2022 at Angas (Aubert 2022) (Table 1). These reports may suggest a contact zone between P. megalopterus and P. carunculatus in the border zone between Loja and Azuay provinces (Barros et al. 2020b). Reports of P. megalopterus in the study area should include photographic evidence to avoid misidentification with P. carunculatus (Barros et al. 2020b).

White-browed Ground-Tyrant Muscisaxicola albilora. An austral migrant to Andean habitats (Fjeldså & Krabbe 1990, Ridgely & Greenfield 2001, Freile & Restall 2018). Inhabits natural open habitats such as páramo grasslands and cushion páramo; less commonly recorded in agricultural lands (Ridgley & Greenfield 2001, Freile & Restall 2018). Eleven observations have been reported within the study area, of which three include photographic evidence (eBird 2023, GBIF 2023) mostly in cushion páramo. On 17 October 2018, one individual was photographed in Migüir (Table 1) (Carrasco 2018). On 16 August 2019, another individual was photographed in the same locality (Table 1) (Molina 2019), and most recently one individual was photographed at Quinoas Lake on 1 August 2020 (Table 1) (Matamoros 2020). These last observations were in páramo grassland.

Bank Swallow Riparia riparia. A boreal migrant that can be seen anywhere in the Andes, often in small groups in association with other swallows (Fjeldså & Krabbe 1990, Ridgely & Greenfield 2001, Freile & Restall 2018). There are three observations in PNC. On 16 November 2006, one individual was observed in-flight with a group of Brown-bellied Swallows Orochelidon murina at Illincocha Lake (Astudillo et al. 2015). On 4 October 2014, one individual was observed at the same locality, and on 1 October 2017, one individual was observed at Toreadora Lake (Table 1) (eBird 2023, GBIF 2023).

Giant Conebill Conirostrum binghami. Rare to locally uncommon, considered endangered in Ecuador (Freile et al. 2019), and near threatened globally (BirdLife International 2021). The populations in southern Ecuador are localized mostly within PNC (Ridgely & Greenfield 2001, Freile & Restall 2018, Astudillo et al. 2020). C. binghami forages in Polylepis woodland or along forest edges searching for invertebrates (Fjeldså & Krabbe 1990, Astudillo et al. 2020, Barros et al. 2020a). Its presumed population decline is attributed to habitat loss and fragmentation of Polylepis woodlands (BirdLife International 2021). Since 2015, 20 different observations have been recorded in several localities inside and outside of the protected areas. Unprotected localities such as Angas, Galgal, Migüir, Rircay, and Tomebamba are also of particular interest (Table 1). In eBird, ~400 observations have been reported for the study area, of which 26 present photographic or video evidence (eBird 2023, GBIF 2023). While many of these reports are associated with localities with remnants of Polylepis forest, C. binghami has also been observed foraging in heterogenous páramo matrix associated with shrubby páramo (Astudillo et al. 2019, 2020, Barros et al. 2020a). Heterogeneous páramo may be important habitat for the species.

Tit-like Dacnis Xenodacnis parina. Distributed throughout the páramo regions of Ecuador and Perú at 3700-4000 m a.s.l. (Fjeldså & Krabbe 1990, Ridgely & Greenfield 2001, Freile & Restall 2018). In Ecuador, X. parina is considered endangered (Freile et al. 2019). There are small and fragmented populations of the species mostly within PNC (Astudillo et al. 2015, 2020, Molina-Abril et al. 2019). Information about its breeding biology and feeding habitats has been compiled in the study area (Aguilar & Iñiguez 2015, Molina-Abril et al. 2019). Habitat of X. parina in populations located ~ 4000 m a.s.l. at Illincocha in 2010-2011 is local to woodlands and shrubs dominated by Gynoxys cuicochensis (Asteraceae) where it forages almost exclusively on extra-floral nectar and arthropods (Aguilar & Iñiguez 2015). Furthermore, in 2017-2018, the breeding biology of five nests was documented at two localities between 3800-4600 m a.s.l. within the PNC (Molina-Abril et al. 2019). Since 2015, the bird monitoring program has reported 204 observations (Fig. 3A), mainly foraging on patchy-distributed Gynoxys bushes in Burgay, Ishcayrrumi, Migüir, Patococha, Rircay, Taitachugo, and Tomebamba (Table 1). In online data bases, X. parina has been well documented with ~2000 observations within the study area (eBird 2023, GBIF 2023). The MCB probably harbours the largest localized populations of X. parina in the country.

DISCUSSION

This study documents the known diversity of birds in the páramos of the MCB and provides a detailed description of a particular biogeographic district of northern Andes province. Fourteen of the 16 threatened bird species associated with the páramo ecosystem occur in the MCB (Freile et al. 2019). Five endemic species, from two centres of endemism in the Andean region (Stattersfield et al. 1998) are also reported in this study. Finally, we reveal new records of at least five species that were unregistered in the study area, particularly in PNC and ARQ.

The MCB should be considered a critical region for conservation of Ecuador's high-altitude Andean birds. The study area provides important habitat for many of birds of conservation concern. For example, the study area appears to represent an important region for endemic species like P. carunculatus (Central Andean páramo) commonly reported throughout the páramo in MCB, and V. gryphus (nationally endangered with small population in southern Ecuador) where new localities are documented within the study area. In addition, C. excelsior (endemic to the central Andean páramo) was commonly found within our monitored localities. Furthermore, we report species strongly associated with Polylepis and Gynoxys woodlands, including M. baroni (endangered and endemic to south-central Ecuador), C. binghami (localized populations within Polylepis forest), and A. griseomurina (endemic to the central Andean páramo). All of these species have consistently been observed within our monitored localities for over five years.

Consequently, the conservation of the Andean bird community depends on the conservation of the páramo habitats that occur across the MCB (e.g., Tinoco et al. 2009, Astudillo et al. 2020, Barros et al. 2023). Information about the habitat affinity of bird species distributed across this biogeographic district was used to understand the effects of habitat alterations (e.g., Astudillo et al. 2019, Tinoco et al. 2019). This is particularly important given that many previous studies of birds in these habitats focused on individual species responses and the potential impact of habitat disturbance (e.g., Astudillo et al. 2016, Tinoco et al. 2009, 2013, Aguilar et al. 2019), rather than focusing on habitat affinities or food preferences (e.g., trophic guilds). A broader understanding of habitat affinities, summarised here, may provide a basis for improving our understanding of the effects of anthropogenic disturbance by emphasizing impacts that may occur at the scale of bird communities (e.g., Botzat et al. 2013, Grass et al. 2013, 2014, Barros et al. 2020a, Tinoco et al. 2021). While this study does not include a formal protocol for habitat sampling, it presents habitat affinities based on field observations which have proven to be very good indicators for exploring diversity patterns in many tropical systems (Laurance 2004, Grass et al. 2014, Powell et al. 2015, Astudillo et al. 2019, Willrich et al. 2019). In addition, several studies have shown the effects of habitat loss and landscape fragmentation on bird habitat guilds at a regional scale (e.g., Astudillo 2014, Astudillo et al. 2014, 2020, Barros et al. 2020a). This study serves as a repository of information of habitat affinities for species and new localities for monitoring páramo bird species in order to facilitate research initiatives as a possibility for securing the conservation of bird diversity in the Ecuadorian Andes.

Only 16% of the páramo grassland in our study area is within the national system of protected areas. Across the MCB, the bird diversity that occurs inside protected areas is similar to some adjacent páramos without formal protection (Barros et al. 2020a). This highlights potential localities to consider for more formal conservation status. When reporting observations, data from online platforms such as eBird and GBIF need to be carefully curated before incorporating it into biodiversity inventories; an exhaustive evaluation via photographic validation and habitat descriptions is recommended. The inclusion of records from regular biodiversity monitoring efforts is therefore crucial in order to complement the data from online sources. Finally, our results show the importance of the Macizo del Cajas, not only because of the sheer number of bird species, but particularly because it harbours grassland birds, which are one of the most affected biological communities adapted to distinct conditions (Brauning 2001, Hamer et al. 2006, Han et al. 2021). The combination of associated habitats within this páramo ecosystem promotes this high species richness. Assessing regional diversity through recognizing the number of endemic and threatened species, as well as habitat affinities, is crucial for the conservation planning processes (Farwig et al. 2008, Latta et al. 2011, Wallis et al. 2016).

uBio

uBio