INTRODUCTION

Cancer of the colon and rectum (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer death in both sex and affects approximately 6% of the overall population of the industrialized countries 1. In the last century the disease was considered as evolution of adenomas, considered the only precancerous lesions of the colon 2, and not the evolution of hyperplastic polyps.

These latter lesions were described in 1927 and throughout the twentieth century have been considered harmless lesions and not capable of causing the CRC 3. In 1970, Goldman 4 was the first to propose a possible involvement of hyperplastic polyp in the carcinogenic process, as the precursor of the adenoma. In 1984, Urbanski et al. 5) have described a polyp with a mixed morphology, both adenomatous and hyperplastic, causing a colonic adenocarcinoma. In 1990, Longacre and Fenoglio-Preiser 6 have coined the term "serrated adenoma" for a lesion characterized by a serrated profile in the epithelium of the crypts and by cytologic dysplasia. Since then, the relevance in terms of carcinogenesis of hyperplastic polyps grew gradually until 2003, when Torlakovic et al. 7 have suggested a subcategory of serrated lesions, discovered in 1990: traditional serrated adenomas (TSA) and serrated sessile adenomas (SSA). These 3 categories (i.e. hyperplastic, SSA and TSA) were firstly officially included in the WHO classification in 2010 8 and are still included in the latest version 9.

This review aims to describe the different forms of this new type of lesions and expand possibilities in the prevention of CRC according to their carcinogenic potentiality.

Genetic modification in the serrated pathway

The carcinogenic process of serrated lesions has been shown to appear completely different compared to the adenoma-carcinoma sequence 10,11. This pathway is characterized by: alterations concerning activation of mitogen and protein kinase regulating the extracellular signal of other intracellular kinases (MAPK-ERK), inhibition of the apoptosis and hypermethylation of DNA and instability of microsatellites.

MAPK-ERK pathway

MAPK-ERK pathway is an important route of cellular response to many extracellular stimuli regulating the growth, differentiation and apoptosis. Two key genes of this kinases group are the KRAS and BRAF; these genes are mutated in a mutually exclusive pathway in the majority of polyps and large bowel cancer 12.

The mutation in the KRAS gene is the first step towards cancer lesions especially in the distal large bowel and in almost 80% of TSA. By contrast, in SSA this phenomenon is rarely detectable 13-15.

Regarding the BRAF gene, this is hardly found in hyperplastic polyps but very frequently (in approximately 75-82% of cases) in the SSA, especially if these are found beyond the distal splenic flexure 15,16.

Both mutations cause a damage in apoptosis and thus favor the increase of further modifications of DNA that will determine the onset of cancer.

Apoptosis inhibition

The phenomenon of inhibition of apoptosis inevitably causes a process of methylation of various areas of the DNA, as indeed occur with extreme frequency in normal cells in elderly (process that frequently induces cell death), and this then promotes the inhibition of expression of numerous other genes with uncontrolled activation of others, creating a dysregulation of the whole process of hemostasis 17-19. Methylation, however, was detected in pre-neoplastic lesions, as if this was a necessary step for the occurrence of other most significant mutations in the cancerogenic process (sustained inhibition of apoptosis is found more in serrated lesions rather than in cancers where the ratio apoptosis-proliferation is not different from that of notserrated- adenocarcinomas) 20.

Hypermethylation of DNA and microsatellite instability

The hypermethylation process has been demonstrated in approximately 30-50% of CRC, and this seems to be tied to the state of CpG islands (particular gene sequences located in the promoters of several genes, including especially those relating to the cellular life cycle) that, if hypermethylated, cause microsatellite instability (rich in CpG islands promoters regions) with different intensity depending on its extent 21-27. Such mutations are defined with the acronym CIMP and graded in low level (CIMP-L) and high level (CIMP-H) depending on the extent of methylation and the number of involved genes 13,14,22-27.

The cancerogenic process of serrated lesions is characterized by an early change in the state of CIMP (already present in the hyperplastic polyp and especially in the SSA), so as in the cells of the mucosa of people with hyperplastic polyposis (clinical condition caused by a greater tendency of creation of serrated lesions and especially with an increased risk of developing colorectal cancer) (17,26,28-30. This phenomenon is summed to the mutations described previously in order to achieve the ideal conditions for the evolution of the serrated lesions to neoplastic lesions.

The instability of the microsatellites, as well as being the mutation phenomenon typical of familial polyposis HNPCC syndrome (syndrome linked to mutations in mismatch repair genes), is a phenomenon demonstrated in sporadic colorectal cancer 31-33. This phenomenon seems to be mainly linked to one of the mismatch repair genes, MLH1, and which would also appear to be closely linked to the process of the carcinogenic pathway in serrated lesions.

This statement is supported by the finding of this condition (MLH1 hypermethylated) in 36% of hyperplastic polyp, in 70% of the SSA and in 86-87% of sporadic colorectal cancers linked to microsatellite instability (MSI) 18,28-31.

As already stated about the CIMP, MSI also exists for a graduation of the phenomenon in low (MSI-L) and high (MSI-H) 18. MSI-H status seems to be linked to the process of carcinogenic pathway of SSA and then especially to polyps arising in the right colon and with the mutation of the base of the BRAF gene; status MSI-L or even the absence of MSI is linked to that of TSA and left sided lesions 7,34,35.

Histological and endoscopic morphology

According to the most recent World Health Organization (WHO) 2019 classification 9, serrated lesions are divided into three types: hyperplastic (micro vesicular subtypes, rich in goblet cells, and mucinpoor), serrated sessile adenomas (SSA) with and without dysplasia (or mixed polyps) and traditional serrated adenomas (TSA) 36.

Hyperplastic polyp

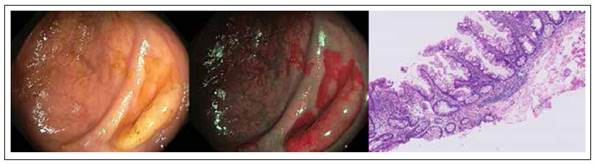

Hyperplastic polyps (HP) appear endoscopically as pale, sessile, small lesions and tend to be found mainly in the sigmoid and rectum 37-39, as shown in Figure 1. These lesions constitute about 80-90% of all serrated polyps (only 3.6-4% of these are present in the right colon) 40,41) and about 10-15% of all colonic polyps 42.

Figure 1 Colonic hyperplastic polyp with white light, narrow band imaging and hematoxylin-eosin stain. Histologic sample shows serrated architecture at the surface without glandular abnormalities.

From the histological point of view, unlike normal epithelium of the colon, HP have a crypt convolved but not branched with a serrated profile of the epithelium at the level of the top half, thus giving the gland a starshaped in transverse section 14.

The subcategories (the most common "Microvesicular", which is characterized by an increased number of goblet cells, and the rarest "Mucin-poor") reported by WHO to date have not shown any clinical relevance but still show biomolecular differences 7.

Serrated sessile adenomas without dysplasia

Serrated sessile adenomas (SSA) without dysplasia appear in average larger than the HP in endoscopic imaging, since more than half have a size greater than 5 mm and approximately 15-20% are larger than 10 mm; these lesions are often covered with mucus, flat, with a yellowish/reddish or similar to the surrounding mucosa and found predominantly upstream of the splenic flexure (about 75%). These lesions constitute about 20% of all serrated lesions and about 10% of all colonic polyps 14,43.

From the histological view, unlike the HP, the architecture of the crypt has more jagged profile and the extension of this phenomenon is up to the basal half; SSA often appear with dilated crypts, extended laterally and behind the muscularis mucosae, forming inverted T or L-shaped crypts. This framework gives to the glands, a star-shaped and enlarged appearance compared to that of HP 44,45.

Serrated sessile adenomas with dysplasia (mixed polyps)

The endoscopic appearance of mixed polyps (MP) is similar to that of the SSA, as well as the pit pattern and distribution in the colon. Such lesions are about 4% of all serrated lesions and about 2% of all colonic polyps 43.

However, from the histological view, MP show areas reproducing the framework of the SSA and others with recognizable dysplasia, recalling the adenomatous structure 42 (Figure 2).

Traditional serrated adenomas

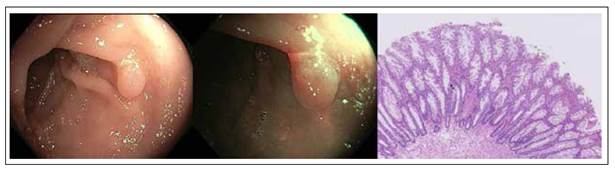

Traditional serrated adenomas (TSA) endoscopically appear more similar to adenomas than to serrated polyps (Figure 3). In fact, they are most often reddish, sessile or pedunculated. These lesions constitute about 2% of all serrated lesions and 1% of all colonic polyps 34.

Figure 3 Colonic Traditional serrated adenomas (TSA) with white light, narrow band imaging and hematoxylin-eosin stain. Histologic sample shows protuberant villiform growth pattern with slit-like serrations and ectopic crypt formations.

From the histological view, TSA have the same architecture of the crypt of the other serrated lesions but with cytologic aspect of widespread dysplasia (hyperchromasia of nuclei, elongation and stratification of nuclei, prominent nucleoli, hypereosinophilic cytoplasm). In cross section this framework gives to the gland a form more typically adenomatous with a pit pattern III according to Kudo classification 45,46.

WASP classification

Thanks to the novel technological improvements, in particular Narrow Band Imaging (NBI), the Workgroup on Serrated Polyps and Polyposis (WASP) has defined the so-called WASP classification 47, which can be used to perform a differential diagnosis between hyperplastic and adenomatous/serrated polyps. This classification uses as first step the NICE classification 47 to differentiate between type 1 polyps, which appear like same or lighter than background; none, or isolated lacy vessels may be present coursing across the lesion and dark or white spots of uniform size, or homogeneous absence of pattern) and type 2 polyps (browner relative to background, brown vessels surrounding white structures and oval, tubular or branched white structures surrounded by brown vessels). Then, the presence of 2 of the following ‘SSL-like features’ (i.e. clouded surface, indistinctive border, irregular shapes and dark spots inside crypts) strongly suggest the presence of SSA.

Risk Factors

The risk of serrated polyps, such for adenomatous polyps, is linked to environmental factors, related to lifestyle and diet. The factors causing an increase of the cancerogenic risk are excessive alcohol consumption, poor intake of folate and obesity 48,49. In the other hand, protective factors are regular use of anti-inflammatory drugs, hormone replacement therapy with estrogen and high calcium intake 48.

The effect of smoking cigarettes constitutes a real paradox, because it is significantly associated with an increased risk of serrated lesions but much less regarding to "serrated" colorectal neoplasms 48,50-53.

Age has been shown to be a factor that does not affect the risk of developing cancer even if the serrated colonic lesions appear earlier than adenomas 48,54,55. Sex, typically a risk factor for adenomatous polyps, increase the risk for SSA and for TSA; the male: female ratio to find a serrated neoplasia is of 1.9:1 56.

Endoscopic management

As all potential oncological lesions, the correct clinical management of serrated lesions is to recognize them during the colonoscopy and subsequently remove them, ideally in-bloc resection, then refer the sample to histological analysis. This approach is common to both adenomas and serrated lesions and is based on the concept that the removal of precancerous lesions means a significant reduction in mortality for colorectal cancer. This hypothesis is true only for the left colon: in fact, for the right colon the data in the literature up until now do not demonstrate a significant gain in terms of cancer mortality regarding the use of colonoscopy as a diagnostic and therapeutic method for such lesions 57.

Among the causes, it should be considered the presence especially in the right colon of SSA; such lesions, as previously illustrated, are difficult to diagnose due to the similar color with the surrounding mucosa and the capacity to be covered by mucus 14,43. In this regard, emerge more strongly as significant parameter of quality in colonoscopy, the rate of detection of serrated polyps which, together with that of adenomas, certify to the endoscopist of specific capacity in performing endoscopic exams with a lower miss rate of interval tumors 58. This parameter would stand at above 5% in the upstream portions of the splenic flexure 59-61, (the rate of detection of adenomas should be higher than 20% 62-64).

This assumption justifies the need of novel technology able to improve the detection of such lesions. Some early data investigated the role of Endocuff 65, which is a device composed of a soft, cylindrical, polymer with flexible circumferential projections that is mounted onto the distal tip of the endoscope. During the withdrawing, the hinged projections of this device flatten the colonic mucosal folds and increase the visualization of the colonic mucosa. A recent study by Baek et al. 66 showed that Endocuff assisted colonoscopy was able to detect more SSA than standard colonoscopy (59 vs 8; p ≤ 0.0001) and significantly increased the SSA detection rate (15% vs 3%; p ≤ 0.0001).

Another potentially useful technology is the G-EYE 67 which is a novel device comprises a reusable balloon integrated on a conventional colonoscope which during the withdrawal phase is partially inflated. This can potentially flatten the colonic folds and stabilize the colonoscope avoiding bowel slippage. In a large randomized controlled study, Shirin et al.67 showed that G-EYE was able to significantly improve the detection of SSA (3 vs 20; p = 0.0026). Finally, a recent meta-analysis of Atkinson et al. (68), including 11 studies, evaluated the role of NBI in the detection of SSA. Results showed that NBI was able to detected more non-adenomatous polyps (OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.06-1.44; p = 0.008) and flat polyps (OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.02-1.51; p = 0.03) than white light endoscopy.

Serrated polyposis syndrome (SPS)

Definition and diagnostic criteria

Serrated polyposis syndrome (Syndrome-SPS), a condition originally known as hyperplastic polyposis, is characterized by a high number of colorectal polyps with serrated architecture. As the SPS is poor known and poor understood condition, it presents a high risk for personal and family CRC.

The diagnostic criteria of the SPS were recently redefined by ESGE guidelines 69: (1) at least 5 polyps resected proximal to the sigmoid colon, 2 of which> 10 mm, or (2) > 20 serrated lesions of any size distributed in the entire colon.

Clinical Features

The clinical characteristics of patients with SPS have been mostly defined on the basis of case-series 70-72. SPS has no predominance of sex and the average age of diagnosis is about 55 years. SPS has long been considered genetic disease but the pattern of inheritance remains unknown: mechanisms suggested both recessive and dominant autosomal inheritance.

Moreover, 10-50% of patients with SPS have a family history of CRC and there is an increased risk of CRC in their first-degree relatives compared to general population 71-74. It’s important to point out that the conventional adenomas may coexist with serrated polyps in patients with SPS 70-72.

Environmental factors (obesity, smoking, increased dietary intake of red meat and fat) may be partially responsible for the onset of serrated lesions (not necessarily SPS) in the left colon. In the right colon, folate intake and family history of polyps and aspirin would have a protective role 75.

Risk of cancer and recommendations for treatment and surveillance

SPS has a high risk of CRC in subjects between 50 and 60 years 70. In published series, approximately 25%70% of patients with SPS had the CRC at the time of diagnosis or the next follow-up 74,76,77. There is a high incidence of synchronous cancer 76 and the CRC shows greater tendency to be localized to the proximal colon in patient with SPS 71.

First-degree relatives of patients with SPS have a higher risk of CRC than the general population 73.

Regular screening colonoscopy should be performed in order to remove potential premalignant lesions and bearing in mind that the detection of the serrated polyp is often difficult (often sessile or flat lesions). The fecal occult blood plays a minor role because serrated lesions have less bleeding tendency than the adenomas.

Recommendations on surveillance strategies

Up to date, several studies showed how traditional serrated adenoma, serrated polyp ≥ 10mm and serrated polyp with dysplasia are similar to conventional adenomas in terms of metachronous advanced neoplasia or CRC risks 78-80. In detail, one population-based randomized study on 12 955 patients screened with flexible sigmoidoscopy 81 and a recent retrospective study 82 evaluating 122 899 patients with 10 years of follow-up showed higher Hazard Rate of metachronous CRC of 4.2 (95%CI 1.3 - 13.3) and 3.35 (95 %CI 1.37 - 8.15) Therefore, these lesions (i.e. traditional serrated adenoma, serrated polyp ≥ 10mm and serrated polyp with dysplasia) need endoscopic surveillance with colonoscopy at 3 years according to the recent ESGE guidelines on post-polypectomy surveillance 83.

Also SPS has been widely discussed in recent national and international guidelines (i.e. USA 59, UK 84, Europe 69, Japan 85, Korean 86 and Australian 87). As above mentioned, SPS patients showed a higher risk of CRC. Therefore, ESGE recommends 69 endoscopic removal of all polyps ≥ 5mm and all polyps of any size with optical suspicion of dysplasia in individuals with serrated polyposis syndrome before and after entering surveillance. Regarding the surveillance, ESGE recommends 69 interval of post-polypectomy surveillance at 1 year after ≥1 advanced polyp or ≥ 5 nonadvanced clinically relevant polyps and at 2 years after no advanced polyps or < 5 nonadvanced clinically relevant polyps.

Since several studies showed an increased incidence of CRC in relatives of patients with SPS 88-90. Therefore, follow-up of these individuals is suggested by ESGE guidelines with colonoscopy from the age of 45 years. In case positive findings, the patient will follow the abovementioned post-polypectomy surveillance. Otherwise, colonoscopy should be performed every 5 years 83.

CONCLUSION

This literature review showed that the serrated lesions are a cauldron with very heterogeneous genetic and biological characteristics causing important clinical consequences.

Such lesions are in fact now recognized as precancerous lesions. This statement is true both for the sporadic forms that familiar ones, and for this reason the scientific world showing more and more interest in knowing the biological processes that underlie them to neoplastic transformation, especially for their significant impact in carcinogenesis in the right colon. Data of the literature show as it’s increasing necessity to have further internationally accepted guidelines regarding the clinical and endoscopic management of these lesions.