1. Introduction

In recent years, social media have had a strong impact on the field of political communication (Elishar-Malkaa, Ariel & Weimann, 2020). In a communicative context previously dominated by the legacy media, social media have become essential tools for political actors, now able to spread their messages without filters or limitations (Casero-Ripollés, 2018; Chadwick, 2013). This dynamic is especially relevant during periods of the electoral campaigns. The fact that these platforms have an open nature enables the appearance of spaces for debate between political representatives and citizens (Miquel-Segarra, Alonso-Muñoz & Marcos-García, 2017).

In this digital environment, platforms such as Twitter, Facebook and Instagram have positioned themselves as an essential element for multiple sectors, and political communication is no exception (Plantin & Punathambekar, 2019; Giansante, 2015). Both parties and candidates have seen the need to incorporate these platforms as new channels through which to disseminate campaign information, share political proposals, mobilize the vote, and get the participation of their electorate (Alonso-Muñoz, Miquel-Segarra & Viounnikoff -Benet, 2021; Jungherr, Rivero & Gayo-Avello, 2020; Pérez-Curiel & García-Gordillo, 2020; Baviera, Calvo & Llorca-Abad, 2019; López-Meri, Marcos-García & Casero-Ripollés, 2017). Likewise, the two-way communication model proposed by these tools is an opportunity for citizens and politicians to interact and dialogue (Bustos Díaz & Ruiz del Olmo, 2016). However, not enough empirical evidence has been found to demonstrate that this occurs in a significant way (Gamir-Ríos et al. 2022; Renobell, 2021; Alonso-Muñoz, Marcos García & Casero-Ripollés, 2017; Stromer-Galley, 2014).

As part of this process of digitizing political communication, the appearance of mobile instant messaging services has also provided a new opportunity to connect political actors with citizens. Smartphones have become the main Internet access device internationally and in Spain (Fundación Telefónica, 2020). Given this transformation in user consumption habits, mobile instant messaging services such as WhatsApp or Telegram have achieved a significant role as communication tools. As Casero-Ripollés (2020) points out, these platforms allow addressing social problems influencing the daily life of citizens, implying that the number of users has grown exponentially in recent years. On the one hand, WhatsApp currently has 2 billion active users worldwide. In Spain, 83% of WhatsApp users employ it daily and, of these, 35% use it to read, share or comment on the news. On the other hand, Telegram has achieved immense popularity in recent years, going from 300 million active users in 2018 to 500 million in just two years. In Spain, 28% of citizens use this application, which is in second place among mobile instant messaging services (Vara-Miguel et al., 2022).

In the political sphere, these digital platforms are a channel that political actors use to spread messages more agilely and directly (Newman et al. 2019; Varona-Aramburu, Sánchez-Martín & Arrocha, 2017). These platforms enable users to create their communities through user groups or broadcast lists (Swart et al. 2019). In addition, unlike Twitter and Facebook, mobile instant messaging services enable sending messages and reaching mobile devices directly without opening the application or searching for a specific account. Also, they allow users to send and receive direct text and multimedia messages without having a high-speed Internet connection (Fernández, 2018). These services facilitate conversations in closed environments since messages reach the devices of each user through private conversations without others accessing them (Vermeer, et al., 2021). This characteristic makes users employ these platforms to create smaller and more private social groups instead of more inclusive and open social media (Valeriani & Vaccari, 2018). In consequence, the emergence of mobile instant messaging services has led to fundamental changes in the field of political communication, modifying the dynamics of electoral campaigns and communication processes between parties and citizens (Zamora-Medina & Losada-Díaz, 2021; Pont-Sorribes, Besalú & Codina, 2020).

Telegram is bursting with great force in the realm of platforms, being the application that has grown the most during 2020 (IAB Spain, 2021). Telegram is a free and free programming service launched in 2013 by the Durov brothers enabling users to send and receive messages freely and confidentially without restrictions. There are two reasons why its use has increased in the political sphere: first, the possibility of establishing a closer and more personal connection with citizens (Gil, 2016), and second, the need for political actors to seek alternatives for more private communication in the face of the public overexposure that users experience in the rest of social media (Piñeiro-Otero & Martínez-Rolán, 2020; Terrasa, 2019). The recent rise of Telegram in terms of political use is also motivated by the limitations introduced by WhatsApp to parties in 2019 in sending mass messaging during the electoral campaign (Alonso, 2019). WhatsApp prohibited computer systems, programs or software to automatize sending messages and spreading them to users massively, thus blocking the accounts that the formations had activated in this service, following the abusive use that certain political formations made of this mobile messaging platform during the electoral campaign.

However, despite its high number of users, its growing use by parties and its multiple potentialities, the study of Telegram is still in its infancy (Alonso-Muñoz, Tirado-García & Casero-Ripollés, 2022; Tirado-García, 2022; Sierra, González-Tosat & Rodríguez-Virgili, 2022). On the contrary, most of the research on the political use of mobile instant messaging services in the campaign focus on WhatsApp (Zamora-Medina & Losada-Díaz, 2021; Gutiérrez-Rubí, 2015; Crespo-Martínez et. al., 2022). Consequently, the study of Telegram from this perspective fills a gap in the previous literature.

The main objective of this research is to know the political use of Telegram in an electoral campaign in a national context. Specifically, it is intended to examine the main functions attributed by the political parties to this platform, the topics on the agenda of the messages broadcast on it and the multimedia and interactive resources used in the publications of the Spanish electoral campaign of November 2019. The case study is relevant as it is the first electoral campaign in which Telegram registers significant levels of use by Spanish parties, in addition to being a political context that has undergone numerous changes in recent years. In this sense, this research makes an innovative contribution by expanding knowledge about the dynamics of political use made by parties in this new type of platform that recently penetrated the field of political communication.

2. Political use of social media and mobile instant messaging services

With the arrival of the internet and, particularly, social media, the field of politics has undergone a powerful communicative redefinition (Giansante, 2015). The possibility of accessing the digital space without limits while creating and sharing content with numerous users has caused political actors to see an opportunity in these platforms to achieve communicative autonomy and release from journalistic mediation that has monopolised the transmission of messages (Casero-Ripollés, 2018; Chadwick, 2013). Political parties and representatives have incorporated social media as essential tools in their communication strategies, mainly during the electoral campaign, when they intensify their presence on social media (Rivas-de-Roca, Morais & Jerónimo, 2022; Elishar-Malka, Ariel, & Weimann, 2020; Stier et al., 2018; Verger, 2015). In this sense, the introduction of social media in the political sphere has led to the emergence of two major positions. It is about the confrontation between the equalization/equalization theory and the normalization theory (How, Hui & Yeo, 2016). The first defends that the digital platforms have equalized the electoral game so that the smaller parties compete on equal terms with respect to the more consolidated ones. For its part, the normalization suggests that the networks have not introduced major structural changes and that the majority parties continue to be so in the online space just as they are outside it.

2.1. Outstanding functions

In these periods, where parties and politicians fight to obtain a preferential place in political and media debate, social media have positioned themselves as an essential channel for self-promotion (Marcos-García, Viounnikoff-Benet & Casero-Ripollés, 2020; López-Meri, Marcos-García & Casero-Ripollés, 2017). In this sense, political actors use social media as a channel to share the proposals that comprise their electoral program and content related to their actions or strategic campaign aspects (Alonso-Muñoz, Miquel-Segarra & Viounnikoff-Benet, 2021; Stier, et al. 2018; Zugasti Azagra & Pérez González, 2016; Lilleker & Jackson, 2013). Likewise, they take advantage of social media as a loudspeaker to promote and viralize their interventions in conventional media thus improving and maximizing their participation and the reach of their messages (Marcos-García, Alonso-Muñoz & López-Meri, 2021; Casero-Ripollés, Feenstra & Tormey, 2016).

Parallel to this self-promotion, in its relationship with users, numerous investigations indicate that social networks such as Twitter or Facebook can be a space through which political actors can directly approach voters, mainly through mobilization and communication explicitly requesting their vote (Stier, et al., 2018; Nielsen & Vaccari, 2013). Several authors point out how the appeal to emotions or the exposure of a close image of the leader are common formulas in these platforms to involve users and appear closer to the electorate (Casero-Ripollés, Feenstra & Tormey, 2016). However, the main potential offered by social media is to boost direct contact with citizens (Bustos Díaz & Ruiz del Olmo, 2016). Their open nature has made them preferred spaces where users can hold conversations about politics with great intensity and depth, thus promoting political and democratic debate (Gutiérrez-Rubí, 2015). Political actors not only can address users directly but also obtain valuable information about the followers’ type of profile while learning about the climate of opinion generated on the network around the issues that mark the news of the moment (Orihuela, 2011; Tumasjan et al., 2010). Despite these potentialities, there is much research that shows how political actors still favour a unidirectional strategy, which does not take advantage of social media as a means of dialogue and direct conversation with their electorate (Renobell, 2021; Alonso-Muñoz, Marcos-García & Casero-Ripollés, 2017; Stromer-Galley, 2014). On the contrary, they concentrate efforts on appealing directly to opponents or even to the media and journalists as a way of viralizing content related to their participation in media spaces (Alonso-Muñoz, 2021).

It is important to highlight how social media have also become a space where political parties and leaders criticize and attack their opponents. In this sense, they take advantage of the disintermediation and openness offered by these platforms to express their discontent and attack the proposals, actions, errors and contradictions of their political rivals (D’Adamo & García Beaudoux, 2016). A dynamic that, according to Marcos-García, Alonso-Muñoz and CaseroRipollés (2021), is mainly influenced by the ideology and position of political actors in government. Thus, the right-wing parties and, at the same time, those in opposition are the ones that use social media the most to highlight the negative aspects of their rivals. Moreover, they usually compare their opponents’ mistakes to their achievements, particularly in the case of leaders.

Social media such as Twitter, Facebook and Instagram have become a showcase through which political candidates highlight their public image and humanize themselves before other users to show a much closer, more intimate and human image in front of the electorate (Karlsen & Enjolras, 2016; Bentivegna, 2015). Therefore, when attacking opponents, leaders not only focus on program or ideology but also on rivals’ particular qualities or personality traits (Maier & Nai, 2021; Marcos-García, Alonso-Muñoz & Casero-Ripollés, 2021). With the introduction of mobile instant messaging services, political parties have intensified their activity on these platforms. Zamora-Medina and Losada-Díaz (2021) suggest that WhatsApp has become a common tool during campaign periods. However, research that focuses on knowing the main functions that political actors grant to other mobile messaging services is still scarce. In this regard, some recent studies have highlighted the role of Telegram as an information and electoral dissemination channel (Alonso-Muñoz, Tirado-García & Casero-Ripollés, 2022; Tirado-García, 2022), as well as mobilization and rapprochement of the candidate. to the voter (Sierra, González-Tosat & Rodríguez Virgili, 2022). In this way, Telegram is constituted, to date, as a tool mainly for political self-promotion.

Actually, most of the previous literature analyzes how citizens use these platforms. In particular, various studies suggest that WhatsApp and Telegram have positioned themselves as spaces to encourage participation and political activism among the most active citizens while promoting political discussion among individuals with less confidence in sharing their political opinions in the online public media (Gil de Zúñiga, Ardèvol-Abreu & Casero-Ripollés, 2019; Newman et al., 2018; Valeriani & Vaccari, 2018). Thus, mobile instant messaging services have become a new channel to learn about politics and interact with political news content (Casero-Ripollés, 2020; Pont-Sorribes, Besalú & Codina, 2020). According to Varona-Aramburu, Sánchez-Martín and Arrocha (2017), this dynamic has been taking place in recent years, since political content has become the most consumed by mobile users. For all these reasons, those functions granted to mobile instant messaging services play a key role in these periods.

This dynamic leads to a first research question:

PI1: What functions are attributed to Telegram by the main political parties during the November 2019 electoral campaign in Spain?

2.2. Thematic agenda and multimedia resources

The possibilities that social media offer to create and disseminate messages have led these to become preferential spaces for political actors to set their thematic agenda, thus avoiding the traditional filter of legacy media (Alonso-Muñoz & Casero-Ripollés, 2018; López-López & Vásquez-González, 2018). Therefore, by spreading their themes and approaches, they manage to draw the attention of citizens and condition political debate and public opinion (Baviera, Calvo & Llorca-Abad, 2019). In this regard, much of the previous literature indicates that, in general, social networks have become bulletin boards for campaign events (Zugasti & Pérez, 2016). However, some studies point out different nuances concerning the social media utilised. Thus, social media established in the communication strategies of political actors such as Twitter or Facebook appear as spaces that mainly broadcast aspects related to political strategy.

In this sense, the messages that deal with intending to form a government and the possible pacts necessary to it stand out (Marcos-García, Viounnikoff-Benet & Casero-Ripollés, 2020). Likewise, they invest little content in sharing messages about science, technology, the environment or terrorism, thus prioritizing a communication strategy based on a few topics (Alonso-Muñoz & Casero-Ripollés, 2018). On the other hand, Instagram operates as a channel where parties and politicians share their values and political philosophy (Marcos-García & Alonso-Muñoz, 2017). Also, the different topics that political actors share on social media are influenced by factors such as the party’s ideology or historical trajectory. Thus, while the right-wing parties pay more attention to economic issues, the left-wing parties dedicate most of their agenda to talking about social policy (Alonso-Muñoz, Miquel-Segarra & Viounnikoff-Benet, 2021). Regarding the party’s history, the emerging parties are the ones that most consider issues related to the development of their electoral campaign and issues involved with the need for democratic regeneration. Meanwhile, the established parties choose to expose the strengths of their electoral programs (López-García, 2016).

These differences between parties are minimum in complementing the shared themes with different multimedia resources. In this sense, images, videos, or other types of audiovisual elements that complement the text are highly used elements by political actors when it comes to completing their messages, mainly due to the positive impact on the viralization of content (Viounnikoff-Benet, 2018; Russmann and Svensson, 2017; Fenoll and Hassler, 2019). According to Marcos-García, ViounnikoffBenet and Casero-Ripollés (2020), the users’ favourite element in the content with political nature is photography on Instagram, whereas the resource that most attracts attention among the Facebook audience is the video.

Those studies that analyze the issues and resources that political actors share on mobile instant messaging services are still scarce. The first investigations suggest that WhatsApp is employed in campaigns to spread messages that directly appeal to the party’s slogans, focused on exalting the union while trying to convince supporters (Zamora-Medina & Losada-Díaz, 2021). For their part, other studies raise electoral proposals as the preferred theme for political parties during the campaign on Telegram (Tirado-García, 2022) as well as issues related to the organization and operation of the campaign (Alonso-Muñoz, TiradoGarcia & Casero-Ripollés, 2022).

From this, the following research questions can be formulated:

PI2: What is the thematic agenda proposed by the main political parties in their communication strategy on Telegram during the November 2019 electoral campaign in Spain?

PI3: What multimedia resources do these actors use to complement the text in their communication strategy on Telegram during the November 2019 electoral campaign in Spain?

3. Methodology

3.1. Method

The methodology includes quantitative content analysis. An analysis model with 15 categories has been used for the study of functions (see Table 1), 20 categories for the thematic agenda (see Table 2) and 7 categories for multimedia resources (see Table 3). In the case of functions and themes, the proposed model adapts respectively to the proposals of López-Meri, Marcos-García and Casero-Ripollés (2017) and Alonso-Muñoz and Casero-Ripollés (2018) for the study of communication strategies in social networks. Our work is an exploratory research of a descriptive type since it is the first approach to the study of a platform of incipient use in the field of digital political communication.

Table 1 Summary of the function analysis model used in this research

| Funciones | |

|---|---|

| Agenda y organización de actos políticos | Actos de campaña (lugar, hora, etc.) |

| Programa/promesas | Deseos, soluciones o valoraciones en conexión con su proyecto de Gobierno. |

| Logros políticos de la gestión/oposición | Alabanza gestión de la formación o el líder |

| Crítica al adversario | Ataques frontales a otros partidos. |

| Agenda/Información mediática | Enlaces a medios de comunicación (entrevistas, debates…). |

| Interacción | Pregunta directa a los usuarios. |

| Repost | Mensajes importados íntegramente de otras redes sociales sin añadir texto. |

| Participación y movilización | Apelación directa al voto o movilización de los votantes. |

| Creación de comunicad – valores/ideología | Fortalecimiento de la ideología del partido. |

| Creación de comunidad – vida personal/ backstage (humanización) | Aspectos de la vida privada de los políticos. |

| Creación de comunidad – diversión/ entretenimiento (humanización) | Pretenden acercarse a los usuarios mediante el uso del entretenimiento |

| Humor | Chistes o memes. |

| Cortesía/protocolo | Agradecimiento, pésame, efemérides. |

| Verificación o denuncia de fake news | Comprobación de bulos o noticias falsas. |

| Otros | Inclasificables según las anteriores categorías. |

Table 2 Summary of the theme analysis model used in this research

| Temas | |

|---|---|

| Economía | Mensajes sobre empleo, paro, salarios, déficit, gasto público, deuda, crisis, impuestos, emprendedurismo, sectores económicos, contratos, autónomos, etc. |

| Política Social | Mensajes sobre pensiones, sanidad, educación, el estado del bienestar, justicia social, igualdad/desigualdad, vivienda, inmigración, natalidad… |

| Cultura y deporte | Mensajes sobre industrias culturales (cine, literatura, arte, etc.) y deporte. |

| Ciencia y tecnología | Mensajes sobre I+D e infraestructura en la Red. |

| Medioambiente | Mensajes sobre contaminación, protección de la fauna y la flora, cambio climático… |

| Infraestructuras | Mensajes sobre carreteras, parques, puentes y servicios de transporte. |

| Corrupción | Mensajes relacionados con el mal uso o abuso de poder público en beneficio personal. |

| Regeneración democrática | Mensajes sobre aspectos democráticos que necesitan ser renovados o eliminados. |

| Juego y estrategia política | Mensajes sobre la formación de gobierno y pactos futuros. |

| Votación y resultados electorales | Mensajes sobre la acción de votar, encuestas, sondeos y valoración de resultados electorales. |

| Modelo territorial del Estado | Mensajes sobre modelo de Estado, nacionalismo, independentismo… |

| Terrorismo | Mensajes sobre legislación, atentados, víctimas… |

| Temas personales | Mensajes sobre cuestiones privada de la vida de los políticos. |

| Organización y funcionamiento de la campaña | Mensajes sobre eventos de campaña y funcionamiento de la misma. |

| Relación con los MMCC | Mensajes sobre aparición de un político en un medio de comunicación. |

| Asuntos exteriores | Mensajes que hagan referencia a la Unión Europea o cuestiones internacionales. |

| Justicia | Mensajes sobre procesos judiciales y reacciones sociales ante estos. |

| Arenga política | Mensajes que exaltan la unión del partido y tratan de convencer a los simpatizantes (eslóganes de campaña). |

| Sin tema | Mensajes importados íntegramente de otras redes sociales. |

| Otros | Mensajes inclasificables según las anteriores categorías. |

3.2. Materials

The sample refers to the general elections campaign held in Spain on November 10, 2019. For the first time in a Spanish electoral campaign, it has been observed that the Telegram platform acquired a significant role as an electoral campaign tool in the communicative activity of political parties.

The following items have been studied: the 15 days of the electoral campaign, the day before the election, the day of the vote and the day after. The sample includes all the messages published by the official Telegram channels of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), Partido Popular (PP), Ciudadanos (Cs), Unidas Podemos, Izquierda Unida (IU), Más País and VOX, which represent 86.7% of the resulting votes in the elections studied.

The sample has been collected by downloading one by one the messages from the Telegram application and has been coded by four members of the research group. It should be noted that messages imported entirely from other social networks have been categorized as “repost” since they do not include original content from the platform studied. The reliability of intercoders has been calculated using Scott’s Pi formula on 150 messages (17.10% of the sample), achieving a level of 0.95 for functions and 0.92 for topics. In total, 877 publications have been examined (Table 4). After its coding, the statistical treatment has been developed with the SPSS program (v.27).

4. Results

In the campaign for the general elections of November 2019 in Spain, it is evident that the main parties usually employ Telegram, publishing messages addressed to their electorate. However, the use of this mobile messaging service is defined depending on the party. As heavy users are the parties with a broader political history that have occupied the Government of the country, especially the two parties that have traditionally formed the two-party system in Spain, PSOE and PP. These two forces add up to 70% of the total messages analyzed. Individually they are situated in percentages that exceed 30%. The rest of the parties analyzed (Citizens, United We Can, Izquierda Unida, Más País and Vox) present percentages between approximately 15% and 5% (Table 4). These data enable us to demonstrate that the political history of the parties determines the use of Telegram in the electoral campaign in terms of publication volume.

4.1. What do political parties use Telegram for? Analysis of the functions in the electoral campaign of 10N

The results enable us to identify four use levels of the functions granted to Telegram by Spanish political parties during the electoral campaign of November 2019.

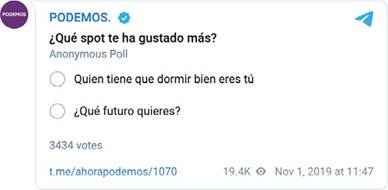

First, the data reveals that the parties mainly use Telegram as a repost or re-diffusion tool (19.6%) (Table 5). The messages that fulfil this function are imported directly from other social media. This reveals how this application is employed to re-diffuse content published in the parties’ accounts in other digital platforms. These messages have not been edited for broadcast on Telegram, so their visual design is that of the original network from which they come. This fact indicates low efficiency in communication terms. The parties use Telegram to extend the reach of the publications they make on social media such as Twitter or Facebook thus reaching a wider audience. The PSOE is the one that uses this function the most in its messages on Telegram (15%) (Table 5) and does so mainly through Twitter reposts to give greater diffusion to the coverage of party campaign events or leaders statements leaders in the media (Image 1).

The second most used function in Telegram is participation and mobilization (18.1%) (Table 5). This category refers to the use of this platform as a medium of direct appeal to voters. There is a high level of mobilizing capacity of the electorate in the messages spread by the Spanish political parties on their Telegram channels. These take advantage of the direct and private communication that characterizes mobile instant messaging services to explicitly demand citizens the vote. They also encourage them to participate in their events while getting involved in the development of the electoral campaign, though this second type of message is less frequent. The PSOE (5.1%) and the PP (4.9%) are the parties that most use this function claiming or requesting the vote (Table 5). The rest use it less frequently and the tone of their messages when asking for votes is less explicit.

At a third level, the data reveals that political actors use Telegram to attack their political opponents (13.9%) and, complementarily, to share their political proposals (11.6%) (Table 5). In terms of criticism, it is directed toward the Government and its president Pedro Sánchez. This resource is used by opposition parties, especially the PP (9.5%) (Table 5) (Image 2). These attacks are directed at the leaders of rival parties to weaken their candidacy and discredit their figure.

On the other hand, the number of messages disseminated by the Spanish political parties about their electoral program also stands out (11.6%) (Table 5, Appendix A1). They use Telegram as an informative brochure of the electoral campaign to display some promises that they will deliver in case they are elected to govern the country. As the party in government, the PSOE shares the most content with this function (5%). The party usually shares short messages along with the campaign image of Pedro Sánchez, introducing some of their electoral proposals, mainly on issues of social policy, education, health or pensions.

Table 5 Functions of the messages broadcast on Telegram by the Spanish parties

| Función | PSOE | PP | Unidas Podemos | CS | IU | Vox | Más País | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repost | 15.4 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 19.5 |

| Participación y movilización | 5.1 | 4.9 | 1.4 | 3.5 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 18.1 |

| Crítica al adversario | 1.4 | 9.5 | 0.1 | 2.4 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 13.9 |

| Programa/ promesas | 5.0 | 3.9 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 11.6 |

| Agenda/ Información mediática | 4.2 | 1.8 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 8.3 |

| Agenda y organización de actos políticos | 2.9 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 7.3 |

| Comunidad: Valores/ Ideología | 1.5 | 2.5 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 7.3 |

| Logros políticos de gestión/oposición | 1.1 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0 | 5.7 |

| Cortesía/ Protocolo | 1.8 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 3.4 |

| Otros | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 1.9 |

| Verificación/ Denuncia Fake News | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 1.1 |

| Comunidad: Vida personal/ Backstage (Humanización) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.9 |

| Interacción | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| Humor | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Comunidad: Diversión/ Entretenimiento (Humanización) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

At a fourth level are the messages related to the party’s agenda, both in its relationship with the media (8.3%) and the organization of political events (7.3%) (Table 5). On the one hand, Telegram serves the political parties as a media loudspeaker to viralize leaders’ interventions in the legacy media. This shows that these media have a significant role in the political use of this mobile instant messaging service. Political parties execute a hybridization strategy to combine the potential of the digital environment with the logic of conventional media, broadcasting the participation of their politicians on television, radio and newspapers on Telegram. Likewise, the parties use this application as a bulletin board for the events that are going to take place during the campaign. In both cases, the PSOE makes the greatest use of these functions (2.9% and 4.2%, respectively) (Table 5).

A similar volume of publications highlights the values and ideology of the party (7.3%) and the political achievements of its management (5.7%) (Table 3). The parties consider Telegram a useful, albeit secondary, space to spread and enhance their administration, with some messages that praise their successes while others contain concepts that identify the party. This way, they appeal to the feeling aroused by identity values to generate an image of unity. This means to approach or appear close to the people who identify with them. In other words, parties seek to improve the loyalty of their electorate through a direct appeal to their ideological bases. In this sense, the PP, located in the opposition, spreads the most messages with these functions (2.6% and 2.5% respectively) (Table 5), but these are low percentages.

The rest of the analyzed functions present low values. This is the case of publications related to questions of courtesy and protocol (3.4%) (Table 5). Messages that verify or denounce hoaxes or false news (1.1%) do not have a significant presence either (Table 3). Although fact-checkers employ mobile instant messaging services with this function, political parties do not use them in their communication campaign strategies for this purpose. It is also detected that the communication strategies of the parties on Telegram avoid encouraging the personalization of politicians since messages related to personal life (0.9%), humour (0.2%) or entertainment (0.1%) (Table 5) are practically non-existent. Given the marginal levels of the use of these functions, there are no notable differences between the parties.

Lastly, the scarce presence of messages published with the function of interacting with the electorate stands out (0.4%) (Table 5). The parties refuse to ask direct questions to users or try to dialogue with them through Telegram (0.4%) (Table 5). The use of this application aims toward a type of one-way communication.

4.2. What do political parties talk about on Telegram? Analysis of the thematic agenda in the electoral campaign of 10N

The results enable us to identify the main topics broadcasted on the parties’ agenda on Telegram during the November 2019 Spanish election campaign. At the first level, those subjects imported directly from other social media predominate (20.1%) (Table 6). It is due to the large number of posts reposted by the parties, and it is particularly relevant in the strategy of the PSOE (16.3%), as it is a party that transfers a large part of the topics of its messages from Twitter to Telegram.

The second dominant topic in the Spanish parties agenda is voting and electoral results (15.1%) (Table 6, Appendix A2). These messages are about surveys, polls, and publications referring to the action of voting. The PP publishes the most messages on this topic on Telegram (4.7%) (Table 6). This aspect is correlated to the fact that this is one of the parties that most uses the function of mobilization in its communication (Table 5). The members of party try to persuade the public while presenting themselves as the best political option, referring to possible electoral results and voting-related issues (Image 3).

Thirdly, issues related to the campaign also have a notable presence in the parties’ agenda on Telegram (11.2%) (Table 6). These messages communicate how the campaign works and the organization of events such as rallies. The data shows that the PSOE is the party that most uses this theme in its messages (3.0%) (Table 6) to support and promote all the actions of the campaign.

In fourth place, the parties use Telegram to viralize their interventions in the legacy media (10.3%) (Table 6). Once again, the PSOE stands out from the rest of the parties as it is the one that publishes the most on this topic (4.9%) (Table 6).

Table 6 Thematic agenda of the Spanish political parties in Telegram

| Tema | PSOE | PP | Unidas Podemos | CS | IU | Vox | Más País | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sin tema | 16.3 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 20.1 |

| Votación y resultados electorales | 3.6 | 4.7 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 2.3 | 1 | 15.1 |

| Organización y funcionamiento de campaña | 3.0 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 11.2 |

| Relación con los MMCC | 4.9 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 2.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 10.3 |

| Economía | 1.4 | 5.5 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 8.6 |

| Medioambiente | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 1.5 | 0 | 5.7 | 8.0 |

| Juego y estrategia política | 1.9 | 4.6 | 0 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0 | 8.0 |

| Política Social | 3.9 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 7.6 |

| Modelo territorial del Estado | 1.5 | 4.3 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.2 |

| Arenga política | 1.3 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0 | 1.5 | 0 | 5.7 |

| Regeneración democrática | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.8 | 2.7 |

| Otros | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 1.6 |

| Corrupción | 0 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.6 |

| Justicia | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 |

| Cultura y deporte | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ciencia y tecnología | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Infraestructuras | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Terrorismo | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Temas personales | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asuntos exteriores | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

In the fifth level, publications on economic issues are prominent (8.6%). These are messages on topics such as employment, unemployment, wages, crisis or taxes. The PP is the party that devotes the most attention to these issues (5.5%). Next are the messages about the intention to build a government or negotiations for possible future agreements (8%). Again, the PP is the dominant party here. Alternatively, messages on social policy are also prevalent, such as those related to pensions, health, education or welfare (7.6%). The PSOE dedicates the most attention to it (3.9%). However, concerning the state model of the country (7.2%), the PP (4.3%) mainly addresses this subject. The messages concentrate on Catalan nationalism in opposition to the independence of Catalonia.

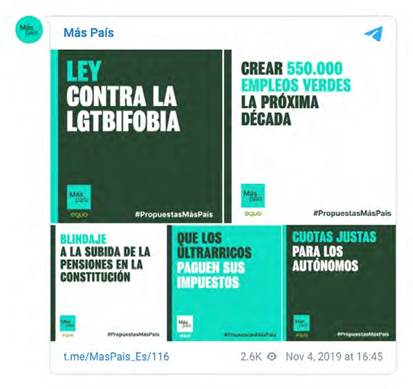

The political speech has less presence on the political parties’ agenda on Telegram (5.7%) (Table 6) (Image 4). The PP (2.3%) is the one that most uses this type of message, very similar to slogans. From their view, democratic regeneration (2.7%), corruption (0.6%) or justice (0.5%) (Table 4) are relegated to minimal relevance. Publications on democratic dysfunctions have a greater role in emerging parties such as Ciudadanos or Más País (0.8% and 0.9%, respectively) (Table 6). Most of these are messages about changes in the electoral law and the need to end the privileges of the elites.

Finally, the parties have not used several themes during the electoral campaign on Telegram. These are culture, sports, science, infrastructure, foreign affairs or personal issues of the leaders. This last case reveals the absence of political personalization in this application. On Telegram, Political parties focus their thematic speech on topics directly related to the campaign and refuse to broadcast personal or private aspects of their candidates or other party members.

4.3. The use of multimedia resources in Telegram in the electoral campaign of 10N

41.5% of the messages include some multimedia resource (Table 7). Those of a visual nature have a preferential role in the communication strategy of the parties. Specifically, video is the most used (29.0%) (Table 7). The use of this resource is twofold: first, it shows voters their interventions in the media (debates, gatherings, interviews...); second, it gives visibility to their speeches at rallies or party events. In some cases, they also broadcast their campaign spots or videos of gratitude to their voters. They are professionally edited videos and not amateurish.

The second of the resources most exploited by the parties on Telegram is the appearance (11.7%) (Table 5). Parties portray photo galleries as a compilation of their acts. These images present the leader standing behind a stand in front of the party supporters. Another way of using the appearance on Telegram is the informative poster, either to publicize the proposals of the electoral program (Image 5) or to show the attainments achieved by the formation. Regarding the formal aspects, there is a predominant use of corporate colours. Also, there is the logo and the campaign slogan in most of the images published through this platform.

Table 7 Use of resources by Spanish political parties on Telegram

| Recurso | (%) |

|---|---|

| No existe | 58.5 |

| Vídeo | 29.0 |

| Imagen | 11.7 |

| Gif | 0.5 |

| Encuesta | 0.3 |

| Audio | 0.1 |

| Sticker | 0 |

| 0 |

Finally, an emerging use of innovative multimedia resources such as gifs (0.5%), surveys (0.3%) (Image 6) and audios (0.1%) (Image 7) (Table 7, Appendix A3) is detected. The gif has a visual nature and consists of the repeated movement of one or several frames for 3-5 seconds. Surveys are brief questionnaires, generally with a single question, which parties use to ask their followers about their opinion on some issue related to their activity. On the other hand, audios are voice notes able to quickly record sounds or conversations.

With the incipient use of this type of resources, political parties seek to foster closeness with citizens since gifs and audios are elements commonly shared in chats between friends or family. Thus, the parties seek to deinstitutionalize relations with their followers while considering their opinions in the party’s decision-making through their followers’ responses in the polls. Despite its limited use, this is a differentiating element of Telegram in comparison to other social media in campaigns.

5. Conclusions and discussion

Our findings reveal, at a descriptive and exploratory level, original contributions to the political use of Telegram in electoral campaigns. Our study is one of the first investigations on this mobile instant messaging service. This application is an emerging channel in the communication strategy of political parties.

Our analysis reveals differences in the levels of activity of the parties in the campaign. The political history of a party conditions the use of Telegram as an electoral tool. We detect a more generalized use of this channel among the traditional parties, which present a significantly higher volume of publications than the rest. The parties with the most extensive history in Spain (PSOE and PP) use Telegram the most in communicating with the electorate. This data differs from the general trend detected in other social media, where emerging parties make more intensive use (Miquel-Segarra, Alonso-Muñoz & Marcos-García, 2017). In the mobile environment, roles are reversed, and the classic parties dominate against the most recent ones. Our results therefore suggest that the political use of Telegram in Spain corresponds to the normalization theory (How, Hui & Yeo, 2016).

Concerning the functions granted by political actors to Telegram, it is noted that parties use this service as a mechanism for redistributing content created for other digital platforms (PI1). This application assumes a secondary role in the communication strategy during the campaign, a differential aspect from what happened in other campaigns in which the parties used Telegram with a primarily informative function (Alonso-Muñoz, Tirado-García and Casero-Ripollés, 2022; Tirado-García, 2022). In other social media, such as Twitter and Facebook, the most exploited function by political parties is political proposals or campaign events self-promotion (Marcos-García, Viounnikoff-Benet & Casero-Ripollés 2020; López-Meri, Marcos-García & Casero-Ripollés 2017), in this case Telegram works as a loudspeaker to redistribute content and maximize its impact among citizens. Despite being a service gaining prominence in the parties’ communication strategies, it is incapable of promoting the creation of original messages adapted to their communicative characteristics. Thus, this platform assumes a secondary and dependent role in relation to other social media.

Another of our findings is that Telegram is employed as a preferred channel for the mobilization and participation of the electorate, hus coinciding with the results pointed out by authors such as Sierra, González-Tosat and Rodríguez-Virgili (2022). The parties take advantage of the direct and private communication that distinguishes this mobile application to ask citizens to vote explicitly and directly, encouraging them to participate in their acts while getting involved in the development of the campaign. This function is mainly exploited by established parties, as they take advantage of the potential of digital media to try to attract users and make them participate in their actions, acts or proposals. This dynamic is in line with previous research focused on Twitter and Facebook (Stier, et al., 2018; López-Meri, Marcos-García & Casero-Ripollés, 2017; Nielsen & Vaccari, 2013). However, unlike what was pointed out by Casero-Ripollés, Feenstra and Tormey (2016) or LópezRabadán y Doménech-Fabregat (2018), the mobilization in Telegram only aims toward requesting the vote. On the contrary, parties do not use this application as a medium of personalizing politics to bring the figure of the leader closer to the electorate. This reveals that it is a medium with low personalization since the messages neither display aspects of the personal life of politicians nor do they resort to the use of emotions. Likewise, the parties do not encourage dialogue with citizens on Telegram either, opting for unidirectional communication.

Finally, another relevant function in employing Telegram is criticizing the adversary. Parties in general, and, above all, those in the opposition, focus a large part of their communication strategy on launching messages attacking their rivals. Beyond criticizing their opponents’ programs, they focus their reproaches on the actions, mistakes, and contradictions committed by their leaders (Marcos-García, Alonso-Muñoz & Casero-Ripollés, 2021; López-Meri, Marcos-García & CaseroRipollés, 2017).

Regarding the thematic agenda in Telegram (PI2), our findings show that this mobile instant messaging service fosters a high level of fragmentation of the political agenda. Most parties articulate their campaign communication around multiple topics without focusing on one or two. Telegram promotes thematic diversification of political messages, a different dynamic from Twitter, where the topics’ agenda is more homogeneous (Alonso-Muñoz & Casero-Ripollés, 2018). On the one hand, voting and electoral results and aspects related to the electoral campaign, and on the other, are the preferred topics for the parties in this application. This reveals the electoral use of Telegram, aspect that already occurred in the political use of this platform in other electoral campaigns (AlonsoMuñoz, Tirado-García and Casero-Ripollés, 2022; Tirado-García, 2022).

Another relevant issue on Telegram’s political agenda is the relationship between political parties and the media. The parties use this mobile application to make the interventions of their leaders visible on television, radio and newspapers, favoring their retransmission. This shows that legacy media play a relevant role in the communication strategy of political parties, since they have a notable presence in this mobile instant messaging service. In Telegram, the parties develop a strategy of hybridization of their communication between legacy and digital media that seeks to enhance the projection of their publications. This reaffirms the importance of the hybridization between new and old media already detected in other social media such as Twitter and Facebook (López-Meri, Marcos-García & Casero-Ripollés, 2017; Casero-Ripollés, Feenstra & Tormey, 2016).

Another relevant finding is the preference of the PSOE for publications on social policy and that of the PP for economic issues. The tendency of the left-wing parties bends towards social issues closer to the needs of citizens while the right-wing parties pay more attention to systemic issues such as the economy. It also highlights the fact that the emerging parties with a progressive tendency are using Telegram to place issues related to the environment or democratic regeneration on the political agenda. Both trends coincide with the previous literature on the thematic agenda of the parties on Twitter during the electoral campaign (López-Meri, Marcos-García & Casero-Ripollés, 2017).

Our last original contribution is the predominance of the visual in Telegram as a priority element when it comes to complementing the text of the messages and the incipient experimentation with new multimedia resources (PI3). Following the visual trend of social media in the context of political communication (Svensson & Russmann, 2017) and other mobile instant messaging services such as WhatsApp (Zamora Medina & Losada Díaz, 2021), video and images are the multimedia resources most used in the communication strategy of the parties on Telegram during the campaign. They are used as communicative vehicles due to their greater persuasive and propagandistic impact (Bustos Días & Ruiz del Olmo, 2016). On the other hand, the parties try to get closer to users and find out their opinions by exploiting the potential of the multimedia resources offered by Telegram. Thus, they begin to use gifs, audio and surveys as a complement to their text messages to get closer and empathize with users. This use is still emerging, but it is innovative compared to other social media. This use is still moderate, but it is innovative compared to other social media.

Our findings can be extended beyond Spain to other geographical contexts, particularly those countries with political and media systems similar to Spanish, such as those in southern Europe (Portugal, Italy, Greece and France). Our research is one of the first on the use of Telegram in an electoral campaign. For this reason, it is highly original and a contribution to the advancing knowledge of this mobile instant messaging service, which occupies an increasingly relevant place in political communication, particularly electoral communication.

texto en

texto en