INTRODUCTION

Obesity and associated metabolic complications are a growing health problem worldwide. Currently, there is a greater implementation of bariatric surgery and with this increase, a higher prevalence of esophageal motor problems and dysphagia has been observed 1. in fact, dysphagia is one of the most common complications encountered in patients after bariatric surgery. In this report, we present a case of dysphagia after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and the approach that was implemented.

CASE REPORT

A 65-year-old woman with no significant previous medical history and normal baseline endoscopy underwent uncomplicated LSG. One year later, she started with dysphagia and progressive regurgitation. Initially, she was managed with proton pump inhibitors and diet for presumed gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). After three weeks, she also developed retrosternal pain and vomiting, thus endoscopy and high-resolution manometry (HRM) were performed in another institution showing signs of achalasia but with an almost normal integrated relaxation pressure (IRP) value (15.6 mmHg). Suspecting a case of achalasia after sleeve gastrectomy, the patient was initially treated with endoscopic dilatation of LES to 30 mm in two opportunities. However, the patient continued with persistent nausea and vomiting after meals. She was referred to our hospital after not observing clinical improvement in the symptoms.

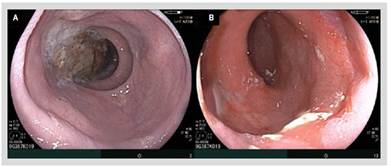

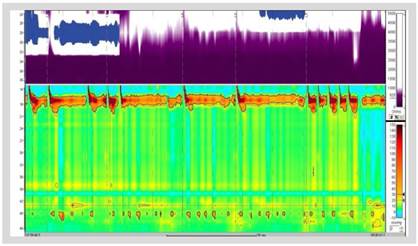

In our hospital, barium esophagram revealed dilated esophagus without contractions and tapering at the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) (Figure 1). Endoscopy showed a dilated and tortuous lumen with solid food content (Figure 2A). In addition, an open oesophagogastric junction was also observed, transposed without difficulty (Figure 2B). HRM revealed aperistalsis with LES resting pressure of 6 mm Hg and IRP of 7 mmHg without panesophageal pressurization (Figure 3). In addition, tomography was performed to exclude other pathologies in which a marked dilatation and tortuosity of the esophagus were evidenced (Figure 4). After discussion in a multidisciplinary meeting, we supposed that one of the possibilities was that the patient probably had a previously undiagnosed alteration of esophageal motility before LSG or that a de novo alteration developed after the surgery. Taking into account that the patient had no previous symptoms and a "normal" endoscopy, a potential diagnosis was: postobesity surgery esophageal dysfunction (POSED) after LSG that was probably mistaken for manometric "primary" achalasia. Surgical treatment was recommended in the absence of clinical improvement with endoscopic dilations and laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy with esophagojejunal Roux-en-Y anastomosis was performed. After surgery, the patient presented a partial improvement in nausea and vomiting, but dysphagia was partially remitted and is now being followed up for 3 months with education on adaptive swallowing methods.

Figure 1 Barium esophagram showing dilated esophagus without contractions and tapering at the lower esophageal sphincter.

Figure 2 A) Endoscopy showing a dilated and tortuous esophagus with solid food content. B) Open lower esophageal sphincter.

Figure 3 High-resolution manometry with aperistalsis with LES resting pressure of 6 mm Hg and IRP of 7 mmHg.

DISCUSION

Obesity is a global epidemic that we must control since it is associated with the development of metabolic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cerebrovascular disease 2. Moreover, obesity is associated with digestive disorders including GERD and esophageal dysmotility 3. This report describes a case of alteration of esophageal motility that developed after bariatric surgery, an entity that is being increasingly recognized due to recent publications 4,5.

In a recent publication, Miller et al. describe that the presence of dysphagia is one of the most common longterm complications after bariatric surgery 1. Kalarchian et al. based on self-reported symptoms found a prevalence of dysphagia symptoms at least once weekly of 43.9% and 16.7% at 1 year after LSG and Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB), respectively 6. Taking into account the high incidence rate of dysphagia in post-operative bariatric surgery patients, we must develop a management protocol that allows us to adequately assess esophageal motility.

As in most cases of dysphagia, performing an upper endoscopy should be the first step to be taken, since it can help us finding obstructive structural alterations such as strictures, esophagitis, and neoplasia. In addition, performing physiological tests such as barium esophagography and HRM will allow us to know how esophageal motility is after surgery. It is crucial to know the type of surgery performed and the time of evolution for the appearance of dysphagia, since it will allow us to guide the work plan. The effects on esophageal motility that can occur after LSG are: decreased LES resting pressures; decreased esophageal contractile vigor and increased frequency of ineffective peristalsis; and increased gastroesophageal pressure gradient (GEPG) and intragastric pressure(IGP) 7-10. The changes that can be seen after RYGB are: increased rates of ineffective esophageal motility without consistent changes in overall esophageal body amplitudes; unchanged LES pressures or length; and decreased IGP and GEPG 7,10-12.

The etiology of the appearance of digestive symptoms may be associated with the appearance of changes in the dynamic motility of the esophagus after surgery 1. Miller et al. found a higher prevalence of esophageal motility disorders after bariatric surgery, mainly achalasia and POSED 1. The appearance of these two types of esophageal motility disorders does not have a clear etiology, but it is postulated that the appearance of de novo achalasia after bariatric surgery may be caused by inadvertent disruption of the vagus nerve during surgery leading to esophageal dysmotility 13. On the other hand, POSED may develop due to an increase pressure in the gastric zone of a noncompliant postoperative stomach after RYGB or because an increased esophageal afterload exerted by LSG 14. This "functional" obstruction distal to the LES may cause achalasia-like pattern, with absent esophageal peristalsis and normal IRP.

Our case has the particularity of a rapid and torpid onset of symptoms. It could be thought that the changes that developed in this patient already had them previously, however the patient had a "normal" endoscopy and no symptoms of dysphagia prior to surgery, which reinforces the idea that the cause of the changes in esophageal motility were due to the bariatric surgery. Moreover, during the second surgery in our hospital, surgeon reported that the vertical gastrectomy from the gastroesophageal junction was very close to the other gastric wall leaving a narrowed gastric pouch. Probably this factor was the cause of the increase in IGP and the subsequent development of POSED.

Experience in the management of POSED and achalasia post bariatric surgery is limited to date. However, there is growing evidence in favor of per-oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) or Heller surgery in cases of achalasia having good symptomatic outcome 15. Miller et al. describe that in the five cases of POSED they found, endoscopic management with dilation and POEM were offered for two patients, education on adaptive swallowing methods for another two, and surgical management was suggested to one patient but was lost on follow-up. Ravi et al. presented four cases of pseudoachalasia secondary to bariatric surgery and in these cases, therapeutic reduction of elevated gastric pressures by dilation of the gastrojejunal anastomosis or conversion of LSG to RYGB led to symptomatic improvement 14. With little information on the best choice for this type of disease, we opted for surgery with clinical improvement and subsequent followup. Despite not yet having a long-term follow-up, the relatively prompt improvement of persistent nausea and vomiting is noteworthy.

This case reinforces the importance of having a quality endoscopy systematic previous a bariatric surgery. An endoscopy with a systematic evaluation will allow us not only to see anatomical alterations like esophagitis, hiatal hernia, tumors, premalignant conditions, etc., but it will also allow us to suspect functional alterations and take a biopsy to detect Helicobacter pylori. Likewise, patients with suspected GERD should undergo preoperative pH and manometry test.

In conclusion, the approach to dysphagia in patients after bariatric surgery should be carried out in a systematic way, guiding us to recognize potential complications such as achalasia or POSED. Timely diagnosis will allow us to offer the best therapy directed at the abnormality generated by surgery (increased LES pressure or intragastric pressure). Despite having potential therapeutic tools for the management of achalasia after bariatric surgery, we still need more studies to define the best therapeutic strategy for patients with POSED.