Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista de Psicología (PUCP)

versión On-line ISSN 0254-9247

Revista de Psicología vol.36 no.2 Lima 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.18800/psico.201802.003

ARTÍCULOS

Professional self-concept: Prediction of teamwork commitment

Autoconcepto profesional: Predicción del compromiso con el trabajo en equipo

Autoconceito profissional: Previsão do comprometimento com a trabalho em equipe

Concept de soi professionnel: prédiction de l’engagement du travail d’équipe

Katia Puente-Palacios1, Maíra Gabriela Santos de Souza2

Universidade de Brasilia, Brasil1, Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária2

1 PhD in Psychology. Professor of the Graduate Program in Social Psychology and the Psychology of Work and Organizations, University of Brasilia. Postal Address: Campus Universitário Darcy Ribeiro, Brasília - DF, 70910-900, Brasil. Contact: kep.palacios@gmail.com.

2 Master’s degree in Organizational Psychology. Researcher at the Brazilian Agricultural Research Company – EMBRAPA. Postal Address: Parque Estação Biológica - PqEB s/nº. Brasilia, DF, 70770-901, Brasil. Contact: souza.maira@gmail.com.

ABSTRACT

The role of self-concept in the context of the way in which work teams function has not been clearly identified, demonstrating the importance of studying this phenomenon. The objective was to evaluate the explanatory power of professional self-concept and personal beliefs in relation to affective commitment. The study was performed with data from 405 Brazilian employees, using a questionnaire with satisfactory reliability indices (α between .75 and .91). The results showed a significant influence of self-concept and personal beliefs in the prediction of commitment (R² = .20). Thus, the vision that workers have of themselves and their beliefs about team work are important predictors of the bonds that they develop with their teams.

Keywords: Professional self-concept, team commitment, teamwork, team effectiveness, personal beliefs.

RESUMEN

El papel del autoconcepto en relación con el funcionamiento de los equipos aún no ha sido claramente identificado, hecho que demuestra la importancia de avanzar en el estudio de ese fenómeno. El objetivo de esta investigación fue identificar el poder de predicción del auto concepto profesional y las creencias personales, en relación al compromiso afectivo. El estudio fue realizado con datos recogidos de 405 empleados brasileños, mediante un cuestionario con índices de confiabilidad satisfactorios (α entre .75 y .91). Los resultados revelan la influencia significativa del auto concepto y las creencias personales en la predicción del compromiso (R² =.20). De ese modo, la visión que los trabajadores tienen de sí mismos y sus creencias sobre el trabajo en equipos son importantes elementos de explicación de los vínculos que desarrollan con sus equipos.

Palabras clave: Autoconcepto profesional, compromiso con el equipo, trabajo en equipo, efectividad de equipos, creencias personales.

RESUMO

O papel do autoconceito no funcionamento de equipes de trabalho ainda não está claramente identificado, fato que destaca a importância de avançar no estudo desse fenômeno. O objetivo desta investigação foi identificar o poder preditivo do autoconceito profissional e das crenças pessoais, em relação ao comprometimento afetivo. O estudo foi realizado a partir de uma amostra composta por 405 trabalhadores brasileiros, utilizando um questionário com índices de confiabilidade satisfatórios (α entre .75 e .91). Os resultados mostram a influência significativa do autoconceito e das crenças pessoais, na predição do comprometimento (R² =.20). Desse modo, a visão que os trabalhadores tem deles mesmos e suas crenças sobre o trabalho em equipe são importantes elementos de explicação dos vínculos que desenvolvem com suas equipes.

Palavras-chave: Autoconceito profissional, comprometimento com a equipe, trabalho em equipe, efetividade de equipes, crenças pessoais.

ABSTRAIT

Le rôle du concept de soi dans le contexte de fonctionnement des équipes de travail n’a pas été clairement identifié, ce qui démontre l’importance de l’étude de ce phénomène. L’objectif était d’évaluer le pouvoir explicatif du concept de soi professionnel et des croyances personnelles par rapport à l’engagement affectif.L’étude a été réalisée avec les données de 405 employés brésiliens, en utilisant un questionnaire avec des indices de fiabilité satisfaisants (α entre 0.75 et 0.91). Les résultats ont montré une influence significative du concept de soi et des croyances personnelles dans la prédiction de l’engagement (R² = 0.20). Ainsi, la vision qu’ont les travailleurs d’eux-mêmes et leurs croyances sur le travail d’équipe sont d’importants prédicteurs des liens qu’ils développent avec leurs équipes.

Mots clés: Concept de soi professionnel, engagement de l’équipe, travail d’équipe, efficacité de l’équipe, croyances personnelles.

Personal characteristics are attributes of utmost importance for understanding human behavior, especially in organizational settings. One of these attributes is the self-concept, described by Lummertz and Biaggio (1986) as a set of beliefs and attitudes that an individual has about him/herself. In the organizational environment, the way workers perceive themselves has been considered an important element in explaining their behavior and performance. Scholars defend the importance of studying this relationship, because empirical studies have shown the existence of associations between the perception that workers have of themselves, and diverse consequences such as work motivation, organizational commitment, citizenship behaviors, turnover intentions, and others (Cowin, Johnson, Craven, & Marsh, 2008; Pierce & Gardner, 2004). Thus, empirically investigating the role of professional self-concept is a relevant contribution to an understanding of organizational behaviors, including those related to teamwork.

Regarding the presence of work teams in the organizational environment, beyond the increase in their implementation, managers and researchers seek to identify global aspects related to teams, and specifics, related to the members, which can best predict good results (Tasa, Sears, & Schat, 2011). This need for better understanding of team functioning has resulted in the publication of hundreds of research reports, diverse meta-analyses, and a number of literature reviews. However, despite the amount of knowledge produced so far, there is still a need to integrate and consolidate what has already been produced, in order to organize this area of knowledge (Mathieu, Maynard, Rapp, & Gilson, 2008; Weingart & Cronin, 2009).

Work teams are defined as groups of three or more members who have a shared work goal, which requires joint efforts of its members to be achieved, carrying out coordinated actions and maintaining complex and dynamic interaction relations (Puente-Palacios & González-Romá, 2013). Considering the wide adoption of teams for work activities and the need for a better understanding of the role of individual-level variables, this study purposes to identify predictors of their effectiveness. Thus, the main objective is to measure the explanatory power of professional self-concept and individual beliefs, in relation to affective commitment of work team members.

Theorizing about the consequents of team processes, Brodbeck (1996) describes performance as one that raises major theoretical and empirical interest. For that author, performance constitutes a set of behaviors required for the work goal to be achieved. On the other hand, Hackman (1987) argues that it is one of the criteria of effectiveness and therefore must necessarily be complemented by other indicators, such as affective results, in addition to the so-called team viability. The latter author also argues that if the task is completed (performance criterion met), but the affective cost to members is high, then they might be unable to continue working together, thereby producing damaging consequences. In this case, therefore, effectiveness would not have been complete.

At the same time, authors such as Salas, Cooke and Rosen (2008) postulate that performance is not limited to reaching the work goal, but also includes the process in which the team engages in carrying out their tasks. They argue that this process involves cognitions, attitudes, and behaviors that are interrelated and occur in an interdependent manner. Thus, coming from this perspective, affective commitment consists of an emotional orientation or bond with an entity (team), developed over the course of a shared work experience, and that constitutes an affective indicator of team effectiveness. Focusing on effectiveness Hackman (1987) argues that involves: a) results achieved with the work performed; b) team’s ability to continue to exist as a performance unit - viability, and; c) affective balance from the experience for the members. Thus, commitment constitutes an indicator of this third criterion.

Regarding the affective responses of team members in relation to the experience of collective work, Picazo, Gamera, Zornoza and Peiró (2015) conclude that satisfaction is a relevant indicator of effectiveness due to its affective nature. In conducting empirical studies, there are many authors who adopt commitment as evidence of effectiveness (Jex & Bliese, 1999; Puente-Palacios, Vieira, & Freire, 2010; Van der Vergt, Emans and Van de Vliert, 2000). From the results of these studies, we conclude that it is appropriate to treat commitment, on an affective basis, as a work team effectiveness criterion.

Commitment to the team is defined by Bishop and Scott (2000) as identification and affective involvement of individuals with a specific team. This definition is very similar to the concept proposed by Mowday, Porter and Steers (1982) for organizational commitment, also on an affective basis. However, it is important to note that the current literature in this field carries on discussions related to the dimensionality of the construct, but recognizes that the affective basis is the one with less arguments to the contrary (Carvalho, Alves, Peixoto, & Bastos, 2011) and is seen as the one more clearly representing the nature of the individual’s affective bond with a particular focal point, which in this case is the team.

Regarding the associations established in the team setting, empirical results show that affective commitment is correlated with the cohesion in the group, turnover intentions, and cooperation between members, among others (Ellemers, Gilder, & Van den Heuvel, 1998; Vandenberghe, Bentein, & Stinglhamber, 2004). These results show that a greater perception of cohesion in the group is associated with a higher tendency of individuals to commit themselves to their work units. As to the turnover intention, team commitment has shown inverse relationships (the higher the commitment, the lower the intention to leave the team) and is indirectly associated with this variable, since the relationship is mediated by organizational commitment. The findings also reveal that high levels of team commitment predict team cooperation, for example, members helping others in carrying out their tasks and staying at work after regular business hours.

In a Brazilian study, it was found that workers who perceive they are more team mate dependents to carry out their jobs, report higher levels of team commitment (Puente-Palacios, Almeidam, & Rezende, 2011). On the other hand, team commitment has been indicated as a mediating variable between group satisfaction and organizational citizenship behaviors. Thus, employees with high levels of satisfaction and team commitment, demonstrate organizational citizenship behaviors more frequently (Foote & Tang, 2008).

In addition to the studies mentioned above, others are focusing on the role of individual characteristics in predicting team effectiveness, measured by affective aspects. Among the results obtained, the role assigned to individual characteristics is observed, such as personality and leadership style, which have demonstrated significant effect on teams’ results (Campion, Medsker, & Higgs, 1993; Costa, Roe, & Taillieu, 2001; Konradt, Andreßen, & Ellwart, 2009), and suggest that worker characteristics can contribute, to a significant degree, in explaining teamwork effectiveness.

One of these characteristics is the self-concept understood as a cognitive structure that organizes the past experiences of the individual, real or imagined, controls the information process related to him/herself, and acts as a self-regulator (Tamayo, 1993). According to Rodrigues, Asmar and Jablonski (1999), the study of self-concept has aroused great interest among social psychologists because it deals with an individual characteristics based on the relationship with the other, and capable of affecting individual behavior, in a number of roles. Self-concept has been studied by psychologists for more than a century and deals with a phenomenon that differs from other self-referential structures, like self-image, self-efficacy, and self-esteem (Souza & Puente-Palacios, 2007; Tamayo, 1981).

Within organizations, self-concept is named professional self-concept and is understood as the image that the individual has of him/ herself as an organizational actor endowed with a certain repertoire of more or less developed competencies. Costa (2002) describes it as a set of perceptions that a person has of oneself in relation to the work and the tasks at hand. In addition, the author states that this characteristic is structured based on individual perceptions that relate to different structures of the self. She also emphasizes that it can be measured based on perceptions regarding the influence of work on health, the competence to carry out a job, the satisfaction of individual needs (professional accomplishment), self-confidence, etc.

With regard to the empirical research, it is worth noting that it has a short history, although results demonstrate its relevance in explaining individual behavior in organizational contexts. In a study conducted in Brazil, it was thus shown that professional self-concept is related to job satisfaction and organizational power (Costa, 2002). Satisfaction was considered a predictor of self-concept, therefore, individuals satisfied with the task and with the work described themselves as competent and fulfilled, while those who were dissatisfied described themselves as less healthy. In contrast, Souza and Puente-Palacios (2011) found that professional self-concept was a significant predictor of satisfaction; due to those results, the direction of the relation (satisfaction and selfconcept) can be questioned.

Focusing in additional relations, a study conducted with public institutions employees, demonstrated that professional self-concept predicts the level of affective organizational commitment, in such a way that workers with high perceptions of achievement and professional competence tended to be more committed to the organization where they worked (Tamayo, Souza, Ramos, Albernaz, & Stela, 2001). Despite these promising results, in another research authors do not identify predictive power of professional self-concept in relation to the impact of training activities (Tamayo & Abbad, 2006). The researchers offer a warning statement that the results they obtained do not diminish the importance of professional self-concept in organizations, and encourage further research to improve the understanding of the role that this personal characteristic plays. Thus, it is considered appropriate to invest effort in investigating the influence of self-concept on organizational results, for example, affective team commitment.

In view of the findings from empirical research, in which the role of professional self-concept is not clearly established, we propose a concomitant investigation of team members’ beliefs on the explanation of team commitment. Beliefs are understood as personal convictions, in this case, related to teamwork. They are basic structures on which attitudes are based, and are conceptualized as information that the subject has about an object, thus involving the cognitive components, according to Fishbein and Ajzen (1975). Attitudes, in turn, are described as a person’s favorable or unfavorable assessments in relation to an object. For the authors, beliefs act as connections (favorable or not) between an object and its attributes.

Focusing specifically on the construction of beliefs about working in teams, Wageman (1995) states that positive information about teamwork serve as building blocks of beliefs, which are acquired and strengthened based on multiple positive experiences of the individual. Thus, workers with strong preferences for individual work probably had few successful experiences working in groups. Also, according to Wageman’s beliefs, although they are strong enough to influence individual behavior, are not immutable. This is because individuals who have preferences for individual work can go on to enjoy working in teams, to the extent they have positive contact with this form of work.

On reviewing the empirical research related to the functioning of work teams, studies involving the investigation of the role of beliefs were found to be scarce. Brant and Borges-Andrade (2014) made an important review of research published inside and outside of Brazil, focusing on beliefs related to work context. According to them, research made in Brazil is new, and started around the year 2000. International publications on that field, however, started around 1970. About the revision performed, those authors emphasize that only 31 international articles were published with focus on beliefs in work context. From the total amount of publications identified, only one focused on the role of beliefs related to team work (Puente-Palacios & Borges-Andrade, 2005).

The study by Puente-Palacios and Borges-Andrade (2005) proposed the existence of a relationship between specific beliefs regarding the effectiveness of teams and satisfaction with the experience of collective work. The results indicated that members who believe that teams are effective units tend to be more satisfied with working in groups, in situations where there is high interdependence of results. Therefore, the belief did not operate in isolation, since it was associated with another predictor. Thus, it participated, as a moderating variable, in the relationship between interdependence of results and satisfaction. This finding supports the decision taken concerning the investigation of the joint role of beliefs and professional self-concept, in predicting effectiveness.

Based on theories related to the phenomena examined in this manuscript, as well as the set of research findings presented, it can be defended that beliefs act as a link connecting the object "work team" to its attribute "effectiveness". Therefore it is argued that individuals with heightened beliefs in the effectiveness of teams will in turn present positive attitudes and consequently a high level of team commitment. According to that, it is expected to verify that professional self-concept and personal beliefs act as antecedents of team commitment. Specifically, it is expected a significant effect of professional self-concept on team commitment in such a way that the more positive view the worker has about himself, the higher the commitment with the team will be. In addition to that, it is expected that higher positives beliefs about the teamwork are associated to more intense commitment with the team.

Method

Participants

Data were collected at two Brazilian private organizations in the information technology business sector. Among the services provided, software development done by work teams can be mentioned. A total of 1,037 questionnaires were distributed, 270 at the first company and 767 at the second. The participants belonged to different departments, and were organized into work teams.

Identification of the work done by teams was carried out by analyzing the characteristics of the tasks and the way the work was organized. In line with adopted definition, each team was composed of at least three members, had a defined working goal, its achievement depended on collective effort, and its members maintained complex and dynamic work relationships. Additionally, in both organizations there was collective performance evaluation, as well as shared rewards for the work done as a group.

The response rate of the questionnaires was 43.5%, and from that total, 46 were excluded from the database for having no variance among all the answers, for leaving more than 50% of the questions unanswered, or for declaring not working in teams. Thus, the following reported analyses were performed based on responses provided by 405 participants. About demographic and functional characteristics, the majority (63.7%) was male, did not lead the team (77.3%), and sample members were attending or already had completed college (64.5%). The mean age was 30.2 years (SD = 7.4). With regard to tenure, the arithmetic mean was 3.2 years (SD = 2.6). As for characteristics related to the teams, the mean number of members per team was 11.4 (SD = 7.8); with most of the teams (58.8%) having between 3 and 10 members. The mean value for team tenure was 1.6 years (SD = 1.7).

Measures

For this study, three measures were used. The Professional Self-Concept scale (Souza & Puente-Palacios, 2007) was measured by 28 items distributed into four factors (achievement, confidence, competence, and health), answered on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always), with Cronbach’s alpha values for the factors ranging from .76 to .90, and item-total correlation between .45 and .69. Additional information about the development process of this measure was reported by Souza and Puente-Palacios (2007). On that publication authors describe the theoretical background behind the measure. Team commitment scale (Puente-Palacios & Andrade-Vieira, 2010), consists of nine statements describing individual’s affective bond with the team. The items are answered on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). The alpha for this measure was .91, factor loadings ranged from .61 to .89, and mean item-total correlation (corrected) was .64. Personal beliefs related to team work (Puente- Palacios & Borges-Andrade, 2005) were measured by 4 items combined into a single factor. The items inquire about the individuals’ beliefs regarding teams in general, that is, if they believe that these work units are effective or not. The instrument is answered using a Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .75, and the factor loadings ranged from .45 to .88, with a mean value of item-total correlation (corrected) of .57. In addition to this set of instruments, respondents offered functional and demographic data with which it was possible to characterize the sample.

Procedure

Data collection was done using paper and intranet questionnaires, and in one of the companies, the questionnaires were administered by the researcher herself and collected immediately after completion by the team members. In the other company, a web page was prepared with the questionnaire, and the link to access it was sent to the human resources manager, who passed it on to the team members. The completed questionnaires remained stored in a database and the researcher was the only person in possession of the access password. The difference in the collecting data strategies followed demands made by participant organizations. In both cases, questionnaires presentation was preceded by the full disclosure to the participants, who were informed about the research content, the confidentiality of the information to be collected, the fact that participation was voluntary, the anonymous nature of the answers, and the possibility of quitting participation at any time. Thus, the ethical principles that govern research involving human beings were respected.

Data analysis

The data was analyzed using the SPSS statistical package. To test the influence of the independent variables on the dependent variable, multiple regressions were performed using the forced entry method (Enter), since this analysis allows the researcher to decide on the order of introducing the variables into the prediction model (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007).

Results

The overall objective of the research was to identify the relationships of professional self-concept and beliefs, with team commitment. Data collection was carried out using two different strategies (in person and intranet) and, the existence of differences in responses collected using these two modes was investigated first. The results showed it was appropriate to combine the data into a single database, since no significant differences were detected.

Once the adequacy of the database for the desired analysis was verified, in terms of size and normality, the identification of multivariate outlier cases was begun, using the Mahalanobis distance. The adoption of this procedure showed 32 cases with a different answers pattern regarding the perceptions of professional self-concept. This group of subjects gave more negative assessments than the non-outlier group, and it was thus decided to remove it from the database. Therefore, the investigation of the relationship between the variables was conducted using the database composed of 373 cases.

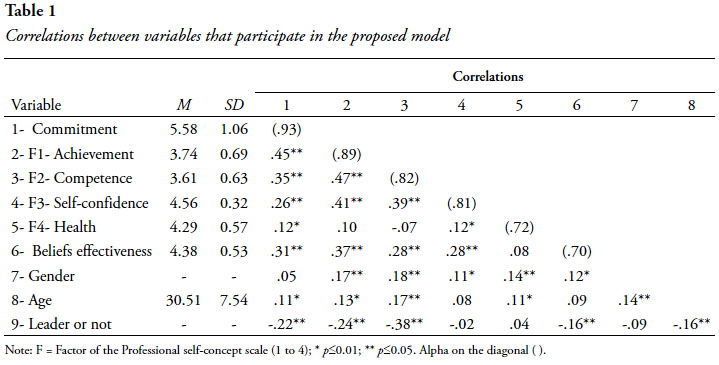

As an initial step to investigate the hypothesized relationships, the existing bivariate correlations between variables, the mean values and the standard deviations were verified. In addition to the information about the model’s variables, demographic and functional data were collected, in order to control their effect at the point of constructing the predictive model. The main results are shown in Table 1. From the control variables, only those with significant correlations with the criterion variable are described in the table.

The mean values reveal that the participants in this study presented levels slightly above the midpoint of the scale for the variable, team commitment (M = 5.58, on a 7-point scale), and believe that work teams are effective (M = 4.38, on a 5-point scale). It is also noted that they perceive themselves as competent and self-confident in relation to their work (M = 3.61 and 4.56, respectively, on a 5-point scale), and present values around the mean for the professional achievement factor (M = 3.74). As for the health factor, it must be stressed that it addresses the individual’s perception regarding the influence that work has on his/her health. Thus, the greater value of the arithmetic mean, the stronger the perception of impact of their work on health. However, since factor items contain negative content, high values indicate the perception that work adversely affects health. Thus, respondents reported noticing a high negative influence of work on their health (M = 4.29 on a 5-point scale).

Correlation analysis also demonstrates the presence of significant association between the variables. Thus, the antecedent variables (or factors) were significantly correlated with the criterion variable, with the strongest effect between achievement and team commitment (r = .45, p≤ .05), and the least intense between health and team commitment (r = .12, p≤ .01). As to this latter association, although significant, it is important to note the low magnitude of the effect. This value means that although the data show that greater commitment is associated with greater impact of work on one’s health, the shared variance is less than 1.5%. Personal believes were also significantly correlated with team commitment (r = .31, p≤ .05). With regard to the control variables, it is observed that gender and being, or not being, the team leader presented significant correlations with almost all variables of the study.

Once the correlations between variables were checked, their contribution in explaining the dependent variable was investigated. The antecedent variables were the four professional self-concept factors (achievement, competence, self-confidence, and health) and the belief in the effectiveness of teams, in addition to the control variables.

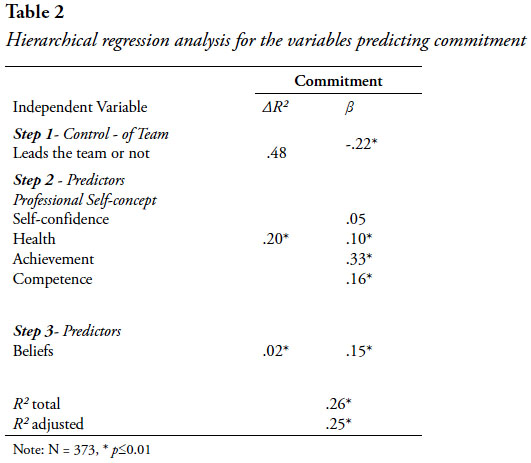

Multiple regression was used to separately quantify the contribution of each variable in explaining the proposed model and the results are presented in the Table 2.

The results summarized on Table 2 demonstrate the steps in which the regression was run and presents standardized regression coefficients (β), R², adjusted R², as well as delta R² at each step. The regression coefficient (β) was significantly different from zero F (11, 356) = 10.74, for p< .01. According to data analysis, in the first step (control variables), only the fact of leading the team, or not, was significant (β = -.22; p< .001). This influence is direct, but negative, and considering the coding criterion adopted, reveals that leaders show greater team commitment than non-leaders. No demographic variables were significant; therefore that information was not presented in the table.

In the next step, the influence of professional self-concept on team commitment is analyzed. Only the self-confidence showed no significant independent participation. Therefore, the greater the perception that health is adversely affected by work, the greater the perception of professional achievement and the greater the perceived competence, the higher will be the reported levels of commitment. The highest value for the beta (β standardized) was for the achievement factor (.33; p< .001). The result indicates that this aspect exerts a stronger impact on the prediction of team commitment than the health and competence factors. Of the factors having a significant effect, the one denominated health was weakest, which again reveals an association of low intensity.

It was also verified, on the third step, that beliefs have direct significant effect on team commitment. The effect strength was .15 (p< .001) and demonstrate that, in addition to the influence of professional selfconcept, to consider teams as adequate structures to perform tasks, impacts positively on team commitment. Even when the size effect is smaller than the effect of others predictors, the theoretical meaning of these results should not be minimized. That is because human behavior is strongly guided by personal beliefs.

Overall, the results obtained show that both the professional selfconcept (represented by some dimensions) as well as beliefs acts as antecedents of team commitment which results in increased predictive power with respect to commitment. These results will be discussed next, considering the theoretical background and the objectives of this study.

Discussion

The ongoing presence of teams in organizations highlights the need for better understanding of their functioning. The results found in this study indicate that individuals’ beliefs about working in teams and the views they have of themselves affect the bonds they develop with the work unit they belong to, and are therefore important variables in understanding the effectiveness of teams, performance units with an increasing presence in the organizational context.

The result of the correlations between focused phenomenon demonstrated the existence of relationships between antecedents and criterion variables. Thus, it was observed that both the professional self-concept factors and beliefs have significant positive links with team commitment. Of these, the strongest association was that of the achievement factor and the weakest, the health factor. In general terms, since the direction of the correlation is positive, the observed values show that the greater the understanding that work is a source of impact or provides the subject something (professional self-concept), the greater the member’s commitment to the team.

Although a relationship of low magnitude (r = .10; p< .05) was found, the association between the health factor and commitment leads to reflection on its meaning. These results reveal the negative impact in the sphere of the worker’s health, the greater the degree of team commitment. In this regard, the reader is cautioned regarding the directionality of the association, since correlation does not imply causality. Thus, we interpreted this result from a reverse viewpoint and considered that individuals more committed to their work may be those who get more involved in it, spend more hours working, and this can result in greater impact of the work experience on their health, being a source of physical fatigue. However, one should also consider the strength of this relationship, which does not exceed 1% (of the shared variance), which is why its meaning should be softened.

As to the relation of the other antecedent variable, beliefs on working in teams, the direction of the correlation was as expected. Thus, the data show that the more favorable the beliefs about working in teams (in general), the more the respondents reported being committed to the teams to which they belong. Although the set of relationships described corroborate the proposed associations, in dealing with bivariate correlations they only suggest possible connections, but without recognizing the participation of other elements that coexist in the organizational setting. For this reason, an analysis of the global predictive model was considered necessary. Thus a regression equation in multiple steps was built.

The results of the regression analyses show that those defined as predictors explain, jointly, 25% of the phenomenon’s variance (R² = .25), and of this total, 20% derives from professional self-concept. The factors, achievement (β = .33; p< .001) and competence (β= .16; p= .01), demonstrate more pronounced participation in the prediction of commitment.

A study performed by Tamayo et al. (2001) revealed similar results and identified that achievement and competence factors were the components of professional self-concept that stood out most in predicting organizational commitment. These authors interpreted the results by highlighting that the more employees were aware of having attained their professional aspirations and ideals (achievement), the more they tended to commit to the organizations, since they perceived that it favored the attainment of those goals. The same seems to happen with the teams, the units under focus in our study. The commitment to a group of co-workers implies acceptance, on the part of the individual, of the norms and objectives, as well as a stronger desire to invest effort for the benefit of the team as a whole and remain a member of it.

Another important result focuses on the association between commitment and the competence factor of professional self-concept. In this respect it is argued that insofar as the worker sees the team as an immediate scenario offering the opportunity to demonstrate one’s potential and allowing one to be seen as a competent actor, the higher the likelihood of developing positive affective bonds in relation to that team. Thus, the factors, achievement and professional competence constitute elements that foster adjustment by the members to the demands of the team, as well as predispose them to invest constructively in its benefit.

Borges-Andrade (1994) argues that, in contrast to what has been found in the international literature, Brazilian researchers have shown that the most significant predictors of organizational commitment are variables at the macro-organizational level. However, it is noteworthy that the aspect usually evaluated is worker perception about the organization, thus, they continue to be evaluations made by workers about macro attributes. Defending the centrality of personal attributes in explaining organizational behavior, authors interested in this issue point out the importance of individual characteristics (values) in predicting worker organizational commitment (Tamayo et al., 2001).

While the intensity of the relationships between individual level variables is not high, it is important to keep in mind that worker characteristics contribute in explaining level of commitment, although a better definition of the circumstances in which this bond can be strengthened is needed. In research on patterns of commitment, developed by Bastos (2000), a connection was observed among a number of personal characteristics and different targets of commitment (organization and career, for example). Thus, there is concrete evidence about the role of personal characteristics in establishing bonds with organizations and teams.

Still focusing on the role of personal characteristics, Mathieu and Zajac (1990) found that among these, the one with the highest positive correlation with organizational commitment was the perception of personal competence. In addition to predicting organizational commitment, the result of the study by these authors suggests that perceived competence at work also helps explain commitment to the team, as shown in the study detailed in this report.

However, it is essential to stress that the factors that constitute self-concept are correlated with one another, and if one of them predicts commitment, then it can be recognized that, to some extent, the others do as well. Therefore, teams composed of members who perceive themselves as accomplished and competent tend to be more committed professionals who can lead the teams, ultimately, to be more effective.

Considering these results we can infer what appears to be a trend in the world of work. Individual characteristics must be understood as important antecedents of workers’ behavior, including in relation to the formation of affective bonds such as the various forms of commitment (organizational, team, career). The magnitude of the identified associations stems from the fact that the studies focus pointedly on one or two attributes, and in the organizational setting countless elements act in a concomitant way in driving behavior.

As previously stated, the objective of verify the role of beliefs, as carried out in this study, becomes important, since it implies the adoption of a predictive model that considers the influence of beliefs, in team commitment. In accordance with what was presented in this article, personal beliefs of team members about work made by teams are associated to the commitment they develop about the team they belong to. It is important to remember that beliefs result from past experiences and represent information about an object, and thus involve cognitive components. In the case of this study, beliefs represent information about work teams and can be positive or negative, depending on the past experiences of the workers.

The results of the performed study show that workers who have positive cognitive references about teamwork, tend to be more committed with their teams than workers who have negative references. Therefore, even when the impact of that variable (beliefs) is not strong, it is significant, and must be taken into account when plan the work of teams. That result is more important if considered affirmation made by Brant and Borges-Andrade (2014). These authors recognize that there is a very small quantity of scientific publications related to that phenomenon. By studying this aspect of the organizational life, better comprehension can be gotten of his behavior, its antecedents and consequents. The results of a publication of Puente-Palacios and Borges-Andrade (2005) also emphasize the results of this study, considering they demonstrate that the belief of team mates in group work is a variable that influences the effectiveness of teams measured, on this case, through an affective result.

These findings also draw attention for their practical implication as they help managers and leaders handle real situations where there is a need to raise the group commitment. Providing successful experiences in the team can produce not only favorable beliefs, but also increase them, thus helping to raise existing commitment levels. These same practices can even strengthen the self-concept, since by working in teams and having shared goals, the success of team work can be experienced as personal success.

Finally, considering the empirical evidences on team functioning, our study contributes in exploring the role of self-concept. The results point to the influence exercised by individual perceptions (self-concept and belief) on the behavior of individuals in the context of work, with respect to the effectiveness of teams, as evidenced from one of its affective results. Understanding the functioning of these performance units expands the possibilities of analysis and intervention in the organizational environment and, from this research, it can then be concluded that self-referent phenomena are important for understanding the behavior of individuals in the workplace and should continue to be studied. However, it should be pointed out that the fact of the data having been collected through self-perceptions makes it difficult to generalize them to another level of analysis (teams) and indicates the importance of further research in order to study the explanatory role of the self-concept and beliefs variables.

Despite this limitation, it is important to emphasize the value of self-report measures and the validity of their use. Spector (1994), in discussing their adoption in studies of the organizational context, demonstrated that the fragility of this type of measure is severe, especially for the evaluation of context attributes, if they are used as variables explaining behavior, which was not the case in the study reported here.

In closing, research results reported in this manuscript also assist in understanding the functioning of teams in Brazil, and more specifically in understanding how to establish affective bonds with these work groups which were explained based on personal attributes. It is important to remark that no research was found in the national or international literature that had studied the influence of self-concept on the effectiveness of teams. Thus, the importance of these findings becomes more salient as this reveals how the perceptions that workers have of themselves, influence the bonds they establish with their work teams, which is a result with great importance in times when organizations are seeking workers genuinely concerned with the performance, effectiveness, and direction of the companies they work for (Bastos, 1994).

REFERENCES

Aiken, L., & West, S. (1991). Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Bastos, A. V. (1994). Comprometimento organizacional: seus antecedentes em distintos setores da administração e grupos ocupacionais. Temas de Psicologia, 2(1), 73-90. [ Links ]

Bastos, A. V. (2000). Padrões de comprometimento com a profissão e a organização: O impacto de pessoais e da natureza do trabalho. Revista de Administração, 35(4), 48-60. [ Links ]

Bishop, J. W., & Scott, K. D. (2000). An examination of organizational and team commitment in a self-directed team environment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 439-450. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.3.439. [ Links ]

Borges-Andrade, J. E. (1994). Conceituação e Mensuração de Comprometimento Organizacional. Temas de Psicologia, 2(1), 37-47. [ Links ]

Brant, S. R. C., & Borges-Andrade, J. E (2014). Crenças no Contexto do Trabalho: Características da Pesquisa Nacional e Estrangeira. Revista Psicologia: Organizações & Trabalho, 14(3), 292-302. [ Links ]

Brodbeck, F. C. (1996). Criteria for study of work group functioning. In M. A. West (Ed.). Handbook of work group psychology (pp. 285-315). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Campion, M. A., Medsker, G. J., & Higgs, A. C. (1993). Relations between work group characteristics and effectiveness: implications for designing effective work groups. Personnel Psychology, 46(4), 823-850. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1993.tb01571.x. [ Links ]

Carvalho, P., Alves, F., Peixoto, A., & Bastos, A. V. (2011). Comprometimento afetivo, de continuação e entrincheiramento organizacional: estabelecendo limites conceituais e empíricos. Psicologia: Teoria e Prática, 13(2), 127-141. [ Links ]

Cohen, S. G., & Bailey, D. E. (1997). What makes teams work: group effectiveness research from the shop floor to the executive suite. Journal of Management, 23(3), 239-290. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639702300303. [ Links ]

Costa, A. C., Roe, R. A., & Taillieu, T. (2001). Trust within teams: the relation with performance effectiveness. European Journal of Work Organizational Psychology, 10(3), 225-244. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320143000654. [ Links ]

Costa, P. C. (2002). Escala de autoconceito no trabalho: Construção e validação. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 18(1), 75-81. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-37722002000100009. [ Links ]

Cowin, L. S., Johnson, M., Craven, R. G., & Marsh, H. (2008). Causal modeling of self-concept, job satisfaction, and retention of nurses. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45(10), 1449-1459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.10.009. [ Links ]

Foote, D. A., & Tang, T. L. (2008). Job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB): Does team commitment make a difference in self-directed teams? Management Decision, 46(6), 933-947. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740810882680. [ Links ]

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, Intention and behavior. An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. [ Links ]

Ellemers, N., Gilder, D., & Van den Heuvel, H. (1998). Careeroriented versus team-oriented commitment and behavior at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(5), 717-730. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.5.717. [ Links ]

Hackman, J. R. (1987). The design of work teams. In J. Lorsch. (Ed.), Handbook of Organizational Behavior (pp. 315-342). New York: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Jex, S. M., & Bliese, P. D. (1999). Efficacy Beliefs as a moderator of the impact of work-related stressors: a multilevel study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(3), 265-276. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.84.3.349. [ Links ]

Konradt, U., Andreßen, P., & Ellwart, T. (2009). Self-leadership in organizational teams: A multilevel analysis of moderators and mediators. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 18(3), 322-346. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320701693225. [ Links ]

Langfred, C. W. (1993). Is group cohesiveness a double-edge sword? Small Group Research, 29(1), 124-144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496498291005. [ Links ]

Lim, B., & Ployhart, R. E. (2004). Transformational leadership: relations to the five-factor model and team performance in typical and maximum contexts. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(4), 610-621. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.4.610. [ Links ]

Lummertz, J. G., Biaggio, A. M. (1986). Relações entre autoconceito e nível de satisfação familiar em adolescentes. Arquivos Brasileiros de Psicologia, 38(2), 158-166. [ Links ]

Mathieu, J., Maynard, M. T., Rapp, T., & Gilson, L. (2008). Team effectiveness 1997-2007: A review of recent advancements and a glimpse into the future. Journal of Management, 34(3), 410-476. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308316061. [ Links ]

Mathieu, J. E., & Zajac, D. M. (1990). A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commitment. Psychological Bulletin, 108(2), 171-194. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.171. [ Links ]

Mowday, R. T., Porter, L. W., & Steers, R, M. (1982). Employee-organizations linkages: The Psychology of commitment, absenteísm and turnover. New York: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Picazo, C., Gamero, N., Zorzona, A, & Peiró, J. M. (2015). Testing relations between group cohesion and satisfaction in Project teams: A cross-level and cross-lagged approach. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(2), 297-307. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2014.894979. [ Links ]

Pierce, J., & Gardner, D. (2004). Self-esteem within the work and organizational context: A review of the organization-based self-esteem literature. Journal of Management, 30(5), 591-622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jm.2003.10.001. [ Links ]

Puente-Palacios, K. E., & Albuquerque, F. J. (2014). Grupos e equipes de trabalho nas organizações. In J. C. Zanelli, J. E. Borges-Andrade, & Bastos, A. V. B. (Eds.), Psicologia, organizações e trabalho no Brasil (pp. 385-412). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Puente-Palacios, K. E., Almeida R., & Rezende, D. (2011). O impacto da interdependência no trabalho sobre a efetividade das equipes. Revista Organizações e Sociedade - O&S, 18(59), 585-603. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-92302011000400003. [ Links ]

Puente-Palacios, K. E., & Andrade-Vieira, R. (2010). Desenvolvimento de uma medida de comprometimento com a equipe. Revista Psicologia, Organizações e Trabalho - RPOT, 10(1), 81-92. [ Links ]

Puente-Palacios, K. E., & Borges-Andrade, J. E. (2005). O efeito da interdependência na satisfação de equipes de trabalho: um estudo multinível. Revista de Administração Contemporânea, 9(3), 57-78. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1415-65552005000300004. [ Links ]

Puente-Palacios K. E., & Gonzalez-Romá, V. (2013). Gestão de equipes. In L. O. Borges & L. Mourão (Eds.), O trabalho e as Organizações. Atuações a partir da Psicologia (pp. 311-338). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Puente-Palacios, K. E., Vieira, A. R., & Freire, R. (2010). O Impacto do Clima no Comprometimento Afetivo em Equipes de Trabalho. Revista de Avaliação Psicológica, 9(2), 311-322. [ Links ]

Rodrigues, A., Assmar, E. M. L., & Jablonski, B. (1999). Psicologia Social (21ª ed.). Petrópolis: Vozes. [ Links ]

Salas, E., Cooke, N., & Rosen, M. (2008). On teams, teamwork, and team performance: Discoveries and developments. Human Factors, 50(3), 540-547. https://doi.org/10.1518/001872008X288457. [ Links ]

Souza, M. G. S., & Puente-Palacios, K. E. (2007). Validação e testagem de uma escala de autoconceito profissional. Revista de Psicologia Organizacional e do Trabalho, 7(2), 95-114. [ Links ]

Souza, M. G. S., & Puente-Palacios, K. E. (2011). A influência do autoconceito profissional na satisfação com a equipe de trabalho. Estudos de Psicologia de Campinas, 28(3), 315-325. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-166X2011000300003. [ Links ]

Spector, P. E. (1994). Using self-report questionnaires in OB research: a comment of the use of a controversial method. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15(5), 385-392. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030150503. [ Links ]

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

Tamayo, A. (1981). Escala fatorial de autoconceito. Arquivos Brasileiros de Psicologia, 33(4), 87-102. [ Links ]

Tamayo, A. (1993). Autoconcepto y prevención. In Rojas, J. R. (Ed.), Quinta Antologia: Salud y Adolescencia. San José de Costa Rica: Caja Costarricense de Seguro Social. [ Links ]

Tamayo, A., Souza, M. G. S., Ramos, J. L., Vilar, L. S., Albernaz, J. V., & Stela, N. (2001). Prioridades Axiológicas e Comprometimento Organizacional. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 17(1), 27-35. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-37722001000100006. [ Links ]

Tamayo, N., & Abbad, G. (2006). Autoconceito Profissional e Suporte à Transferência e Impacto do Treinamento no Trabalho. Revista de Administração Contemporânea, 10(3), 09-28. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1415-65552006000300002. [ Links ]

Tasa, K., Sears, G., & Schat, A. (2011). Personality and teamwork behavior in context: The cross-level moderating role of collective efficacy. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32, 65-85. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.680. [ Links ]

Van der Vegt, G., Emans, B., Van de Vliert, E. (2000). Team members’ affective responses to patterns of intragroup interdependence and job complexity. Journal of Management, 26(4), 633-655. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600403.

Vandenberghe, C., Bentein, K., & Stinglhamber, F. (2004). Affective commitment to the organization, supervisor, and work group: Antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64(1), 47-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(03)00029-0. [ Links ]

Wagmen, R. (1995). Interdependence and group effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(1), 145-180. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393703. [ Links ]

Weingart, L. R., & Cronin, M. A. (2009). Teams research in the 21st century: a case for theory consolidation. In E. Salas, G. F. Goodwin, & C. S. Burke (Eds.), Team effectiveness in complex organizations. Cross-disciplinary perspectives and approaches (pp. 509-524). New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group. [ Links ]

Recibido: 30 de junio, 2017

Revisado: 17 de octubre, 2017

Aceptado: 22 de febrero, 2018