Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Industrial Data

versión impresa ISSN 1560-9146versión On-line ISSN 1810-9993

Ind. data vol.24 no.2 Lima jul./dic. 2021 Epub 31-Dic-2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/idata.v24i2.20971

Production and Management

Motivation of Human Talent and Its Relationship with Citizen Service in a Local Government in Lima, Peru, 2017

1Degree in Administration. Currently working as an independent consultant. (Lima, Peru). E-mail: patriciacalleterrones@gmail.com

This research aimed to establish the relationship between motivation of human talent and citizen service. From a population of 3192 local government workers, a sample of 343 at 95% confidence level was obtained. A Likert-type scale survey was used for data collection. Based on the results, variables “motivation of human talent” and “customer service” are positively correlated (0.57). The dimensions of variable “motivation of human talent” are: “intrinsic motivation” and “extrinsic motivation”; the dimension of variable “citizen service” is “service provided by the staff”. It is concluded that the motivation of human talent is related to citizen service.

Keywords: motivation; human talent; citizen service

INTRODUCTION

The relationship between the motivation of human talent and customer service is a subject of analysis, as this pairing has been and will always be a constant in any public entity. This research contributes to knowledge, as it delves into the study of a topic as relevant as the human factor. It is an innovative study since the findings propose novel solutions to the problem. Consequently, the results obtained provide a reference for future research beyond local governments, since their scope is applicable to any service provider organization.

Mankind is constantly facing technological, economic and social changes that have resulted in digital transformation, automation and artificial intelligence. In this regard, Peña and Villón (2018) argue that “los tiempos actuales están sujetos a cambios drásticos y exponenciales que dan paso a la realización de procesos de cambio en secuencia dentro de las organizaciones [current times are subject to drastic and exponential changes that lead to the realization of sequential change processes within organizations]” (p. 179). Arguably, then, there is a looming opportunity for organizations to break paradigms, innovate and adapt to the changes brought by technological disruption; among them, the redesign of the workforce and of workspaces that facilitate productivity, for it is believed that the human approach must be prioritized above all else.

As a response to the demands in developed countries, organizations look inward, prioritize the empowerment and development of their personnel’s skills, and only recruit new employees when necessary. However, in Latin America, some organizations have yet to consolidate this practice.

Therefore, both public and private organizations agree that the achievement of objectives, sustainable development and relevance depends to a large extent on their workforce, and that staff motivation is an essential part of this process.

There are three levels of government in Peru: national government, regional government and local government. The latter is citizen-oriented and therefore closer to the citizen in terms of the provision of public services. Thanks to the aforementioned advances, citizens are forcing entities to be more efficient and responsive. Staff members are the ones who, directly or indirectly, provide services to citizens.

It is therefore important that an organization’s employees feel at ease with the nature of their work and their working environment. However, the existence of different work regimes, long working hours, working conditions, salary issues and informal contracting in the form of service providers, among other shortcomings neglected by governments, distances them from this vision and, in short, undermines the motivation of human talent.

Hence, the objective of this research is to determine the relationship between the motivation of human talent and customer service, which are variables defined according to the problems of the local government under study.

Motivation of Human Talent

Since ancient times, even before the rise of psychology as a science, there has been interest in discovering and understanding human behavior and the reasons that motivate people to act in a certain way (Ibáñez, 2011). Scientific studies developed throughout history have provided theories related to motivation in the workplace, all of them with different approaches, but with which it has been possible to understand the importance of human behavior.

Regarding motivation, Maslow (1991) states that it is “constant, never ending, fluctuating and complex” (p. 8). Yarce (2001) maintains that this phenomenon is the “fuerza o impulso interior que mueve hacer algo […] por diversos motivos: unos de tipo extrínseco (materiales), otros intrínsecos (satisfacción) y otros trascendentes (servicio a otros) [inner force or impulse that moves people to do something [...] for various reasons: some extrinsic (material), others intrinsic (satisfaction), and others transcendent (service to others)]” (p. 169). Furthermore, he points out that values support motivation. Meanwhile, Vaca (2017) states that “la motivación es un aspecto de relevancia en la orientación de acciones y conforma un elemento central que conduce las personas a realizar sus objetivos [motivation is relevant in guiding actions and is a key element that leads people to achieve their goals”] (p. 102).

Regarding work motivation, it can be understood as the “resultado de la interrelación del individuo y el estímulo realizado por la organización con la finalidad de crear elementos que impulsen e incentiven al empleado a lograr un objetivo [result of the interrelation of the individual and the stimulus provided by the organization in order to create elements that drive and encourage the employee to achieve a goal]” (Peña & Villón, 2018, p. 185). In Herzberg’s words, “motivation is a function of ability and a function of the opportunity to use that ability” (Riding, 1973)

Peña and Villón (2018) therefore infer that:

La teoría de Herzberg, se manifiesta en ver al empleado como el ser que busca el reconocimiento dentro de la organización y la satisfacción de sus necesidades y que al satisfacer estos dos objetivos, su motivación se convertirá en el impulsador para asumir responsabilidades y encaminar su conducta laboral a lograr metas que permitirán a la organización lograr con éxito su razón de ser, con altos niveles de eficacia [Herzberg’s theory is manifested by considering the employee as the being who seeks recognition within the organization and the satisfaction of their needs and that by fulfilling these two goals, their motivation will become the driving force to assume responsibilities and direct their work behavior to achieve goals for the organization to successfully achieve its mission statement, with high levels of efficiency]. (p.180)

Work motivation plays a vital role in human beings, since it determines their behavior at work and often in their personal lives; as a significant element, it must not go unnoticed in organizations because their success or failure depends on the human factor.

Several theories on work motivation provide valuable contributions; however, in this research we will focus on Frederick Herzberg’s two-factor theory. His studies sought to demonstrate “the concept that man has two sets of needs: his need as an animal to avoid pain and his need as a human to grow psychologically” (Herzberg, 1966, p. 95). Therefore, two kinds of factors resulting in job satisfaction and dissatisfaction were identified: intrinsic factors and extrinsic factors.

These are two independent sets of factors, each of which is made up of a specific dimension (Herzberg, 1966). Thus, intrinsic factors, being inherent to the human being and present in the job, give meaning to its nature, activate employees’ abilities and arouse in them a high level of motivation. These are: achievement, recognition, work itself, responsibility and growth.

On the other hand, extrinsic factors are linked to the conditions and “his relationship to the context or environment in which he does his job” (Herzberg, 1966, p. 97); that is, the work environment. They are composed of: organizational policy and administration, supervision, remuneration, interpersonal relations and working conditions.

Although these two factors have different dimensions, they do not have an opposing effect. Herzberg (1966) explains it with an analogy “The opposite of job satisfaction would not be job dissatisfaction but rather no job satisfaction; similarly, the opposite of job dissatisfaction is no job dissatisfaction, not satisfaction with one’s job” (p. 100). It is clear to this author that both are aimed at satisfying the needs of the personnel, but it is the intrinsic factors that generate job satisfaction (Herzberg, Mausner, & Bloch, 1959). Consequently, these factors translate into lasting achievements at work; on the contrary, extrinsic factors produce attitudinal changes that last only a short time. This is because the extrinsic factors are directly related to the worker’s actions.

Manso (2002) mentions that Frederick Herzberg introduced his own conception of “la vida, la naturaleza del hombre y la función que el trabajo juega en el desarrollo y el crecimiento espiritual de la persona [life, the nature of man and the role that work plays in the development and personal spiritual growth]” (p. 82).

Although this theory has been around for many years and has been criticized for the reliability of its methodology, it continues to be widely used by public and private organizations. Herzberg not only accepted criticisms, but also considered them justified. In response to them, this renowned author published in 1966 the book Work and the Nature of Man as a sequel to The Motivation to Work of 1959, precisely because the model of workplace behavior set out in his first publication “has led to a gratifying number of studies designed to replicate and test validity of the theory” (Herzberg, 1966, p. 17). Indeed, in the repetitions of the survey to test the theory in question, a larger number of employees and entities were included. Therefore, the results obtained proved to be supported by the theory originally proposed (Herzberg, 1966).

Not in vain is this model a main reference, a consultation tool and a model for the development of the theory of other authors (Manso, 2002). He adds that, since this theory came to light, “ha recibido más atención y generado mayor cantidad de investigaciones que cualquier otra teoría sobre motivación y satisfacción laboral [it has received more attention and generated more research than any other theory on motivation and job satisfaction]” (p. 85). Herzberg’s theory is also credited with having influenced the enrichment of man's work as a reinforcement of the motivational factor in organizations.

People are the ones who make the achievement of the objectives viable, for organizations without people and their talent are nothing. According to Miranda (2016), we should not refer to them as the human resource, “no son seres inertes, sin sentimiento, como son los recursos materiales, técnicos y financieros…, el manejo de estos es sistemático y rutinario; en cambio, hablar de talento humano se convierte en un concepto más complejo [they are not inert beings, without feeling, as are the material, technical and financial resources..., the management of these is systematic and routine; instead, talking about human talent becomes a more complex concept]” (p.21). Following this line, Jericho (2008) mentioned “¡qué poco me gusta llamarles Recursos humanos y qué injusto creo que es tratar a las personas como un recurso más! [how little I like to call them Human Resources and how unfair I think it is to treat people as just another resource!]” (p. 60). In short, people are thinking beings, with feelings, emotions and talent, often ignored.

The word talent comes from the Latin talentum, related to aptitude or intelligence, this term can be “utilizarse para nombrar tanto a la capacidad en sí como a la persona que cuenta con dicha capacidad [used to name both the capacity itself and the person who has that capacity]” (Pérez & Merino, 2013, para. 2). Talent is also linked to the human being’s own ability and innovation, which can also be developed through praxis and training (Pérez & Merino, 2013).

In fact, if people are the most important thing in an organization, simply having them is not enough, “debemos desarrollar, potenciar y retener a los mejores talentos [we must develop, empower and retain the best talents]” (Miranda, 2016, p. 27). Along these lines, Jericho (2008) emphasizes that talented people achieve “resultados superiores, pero necesita estar en una organización que se lo permita… y que lo motive [better results, but they need to be in an organization that allows them to do so... and that motivates them]” (p. 72). Admittedly, people do not develop within an organization in isolation, but require leaders who care about their well-being regardless of the position they hold.

Based on the above, it can be stated that the motivation of human talent is a process initiated from internal and external stimuli of the personnel, which drives their capacity for the development of activities towards the achievement of organizational objectives, guiding their behavior based on their personality and values.

In the workplace, “Motivation, then, takes place within a culture, reflects an organizational behavior model, and requires excellent communication skills”. (Newstrom, 2011, p.107). Indeed, organizations demand that employers are able to identify and understand the drives and needs that motivate their workers. This is a continuum, because once they are met, other needs will appear and continue to motivate whichever goals the person wants to achieve (Peña & Villón, 2018). It is therefore essential to have adequate leadership, supported by ethics and human sensitivity to build respect, trust, commitment and motivation among staff, so as to contribute to the provision of good customer service.

Consequently,

si partimos del supuesto de que los valores organizacionales influyen en las percepciones, motivaciones y comportamientos de las personas en su trabajo, es en los organismos públicos donde tienen un mayor impacto, en tanto que la principal función de las acciones del Estado tiene como finalidad la búsqueda del bien común [on the assumption that organizational values have an influence on the perceptions, motivations and behaviors of people at work, their greatest impact is on public agencies, since the main function of the State’s actions is aimed at the pursuit of the common good]. (Marsollier & Expósito, 2017, pp. 35-36)

Citizen Service

For Aristotle, “ciudadano en general es el que participa activa y pasivamente en el gobierno [in general, a citizen is someone who actively and passively participates in the government]” (Bueno, 2017, p. 17); thus, there is a close relationship between citizens and public administration.

The boom of technology has made communication with the citizen in real time easier and public entities make technological tools available to them to make their procedures feasible. However, as humans are by nature social beings, they also want to interact in person with the representatives of an entity, which is why technical preparation and human quality in customer service are required.

According to Arrupe and Milito (2015), citizen service is defined “como el conjunto de procesos, tareas, herramientas y canales, a través de los cuales se desarrolla el contacto con éste. El objetivo puede ser diverso: brindar información, recibir consultas, ofrecer y prestar servicios, recibir pedidos, quejas, reclamos, sugerencias, etc. [as the set of processes, tasks, tools and channels through which contact with citizens is established. There are several reasons for it: providing information, receiving queries, offering and providing services, receiving requests, complaints, claims, suggestions, etc.]” (p. 170). In Peru, the service channels are “medios o puntos de acceso, a través de los cuales la ciudadanía hace uso de los servicios provistos por las entidades públicas, incluye espacios de tipo presencial (oficinas y establecimientos), telefónico (call-centers), virtual (plataformas web, e-mail) y móvil [means or access points through which citizens make use of the services provided by public entities, including face-to-face (offices and establishments), telephone (call-centers), virtual (web platforms, e-mail) and mobile spaces]” (Presidencia del Consejo de Ministros [PCM], 2015, p. 113).

Such interaction entails shortcomings, and therefore, new paradigms focused on improving citizen service processes. For that purpose, standards, policies and manuals that must be applied by all public entities without exception have been created (López, Olivera, & Tinoco, 2018).

This concern for the citizen resulted from the poor practice of bureaucratic administration, manifested by user dissatisfaction. Thus, at the end of the 20th century, quality assumed a preponderant and unavoidable role in the field of Public Management, leading to the initial interest of international organizations in the implementation of the New Public Management Model (Corrales, n.d.; Schröder, 2006).

Taking said model as a reference, the Peruvian State introduced and implemented substantial improvements to modernize public administration in our country (Corrales, n.d.). Therefore, public service is an activity specific to the State “organizada conforme a disposiciones legales reglamentarias vigentes, con el fin de satisfacer de manera continua, uniforme y regular las necesidades de carácter colectivo [organized in accordance with current regulatory legal provisions, in order to continuously, consistently and regularly meet the community’s needs]” (Fernández, 2015, p. 21). In other words, it aims to provide quality services to the citizen. However, the efforts made by the State to improve citizen services have been insufficient.

Public organizations, despite having adopted some processes from private administration, still focus on monitoring, control and compliance with regulations; apparently, this is due to the rigid bureaucratic system. Such centralism often underestimates and neglects the importance of the human labor process, without prioritizing its strength in terms of its effectiveness in ensuring that citizens receive quality service. Unfortunately, said weakness is reflected in various manifestations of dissatisfaction on the part of the citizen. Public entities should not overlook such a situation, given that their supreme purpose is to serve the citizen.

As local governments are closer to citizens, they are “responsables de implementar acciones de fortalecimiento y cambios internos destinados a mejorar la atención y hacer efectivo el acercamiento entre la administración y los vecinos [responsible for implementing strengthening actions and institutional changes aimed at improving service and making effective the interaction between the administration and the neighbors]” (Arrupe & Milito, 2015, p. 169).

There is a tool that establishes a connection between citizens and public entities: the Texto Único de Procedimientos Administrativos [Single Text of Administrative Procedures] (TUPA), a management document that “incluye la relación de los servicios prestados en exclusividad, entendidos como las prestaciones que las entidades se encuentran facultadas a brindar en forma exclusiva [includes the list of services provided on an exclusive basis, understood as the services that entities are authorized to provide on an exclusive basis]” (RSGP N.° 004-2018-PCM/SGP, 2018, p. 1). Such relationship is key, as it creates opportunities for public entities to constantly improve and provide quality services. Therefore, the TUPA should be known by all public servants and citizens.

It should be noted that

el ciudadano ha evolucionado, ya no es un simple receptor de bienes y servicios públicos. En la actualidad, es protagonista de asuntos de interés general, está más informado, más atento y es más exigente, pretende servicios y productos de calidad [citizens have evolved, they are no longer mere recipients of public goods and services. Nowadays, they are the leading actors in matters of general interest, they are more informed, more attentive and more demanding; they are looking for quality services and products]. (Arrupe, & Milito, 2015, p. 172)

López et al. (2018) mention that there is currently no consensus on the definition of quality, however, several authors agree that it is “la percepción del cliente sobre el producto o servicio recibido [the customer's perception of the product or service received]” (p. 8). In the words of Zeithaml, Parasuraman, and Berry (1993), “service quality, as perceived by customers, can be denned as the extent of discrepancy between customers’ expectations or desires and their perceptions” (p. 21). In turn, Grönroos (cited by Duque, 2005) points out that, “una buena evaluación de la calidad percibida se obtiene cuando la calidad experimentada cumple con las expectativas del cliente, es decir, lo satisface [a good assessment of perceived quality is attained when the quality experienced meets the customer’s expectations, that is, satisfies him]” (p. 71).

According to Kotler and Armstrong (2012), perception is the “process by which people select, organize, and interpret information to form a meaningful picture of the world” (p. 148). As for expectations, Matsumoto (2014) states that they “son las creencias sobre la entrega del servicio, que sirven como estándares o puntos de referencia para juzgar el desempeño de la empresa. Es lo que el cliente espera de un servicio [are beliefs about service delivery, which serve as standards or benchmarks for judging company performance. It is what the customer expects from a service]” (p. 185). Regarding service experience, Laveglia (2018) notes that it is the “creación de valor desde la perspectiva del cliente [creation of value based on the customer's perspective]” (para. 2).

Service quality is closely related to what the customer wants, therefore, conferring an intrinsic component to it. Indeed, “desde la percepción del ciudadano, la calidad de los servicios públicos siempre tendrá un elemento subjetivo [from the citizen’s perception, the quality of public services will always have a subjective element” (Martínez, 2016, p. 205). Fernández (2015) adds that because of this characteristic of service quality, which for one customer is a quality service, is not so for another. “Es así, que si el cliente percibe que el producto o servicio no le aporta valor, lo clasificará con un bajo nivel de calidad [Thus, if the customer perceives that the product or service is not of value to him, he will consider it as a low level of quality]” (López et al., 2018, p. 8).

Regarding public agencies, service quality is defined by the PCM (2015) as the “percepción que el ciudadano tiene respecto a la prestación de un servicio; que asume la conformidad y la capacidad del mismo para satisfacer sus necesidades [citizen’s perception of the provision of a service, implying the compliance and capacity of the service to meet their needs]” (p. 115). Therefore, citizen satisfaction is defined as “la valoración que hacen las personas sobre la calidad percibida en aquello que recibe de la entidad pública [people’s assessment of the perceived quality of what they receive from the public entity]” (PCM, 2021, p. 14).

According to López et al. (2018), the concept of public value was introduced by Moore in 1998, who pointed out that this is created by the State through services, rules, regulations, among other actions. “El valor público se crea cuando las instituciones públicas generan resultados efectivos a las necesidades y expectativas de las personas, y se orienta a generar beneficios a la sociedad [Public value is created when public institutions provide effective solutions to people’s needs and expectations, and it is oriented to benefit society]” (PCM, 2021, p. 14) Precisely, public value consists of that benefit aimed at the citizen. However, it is necessary to emphasize that, “la provisión de servicios públicos no necesariamente genera valor, sólo cuando éste logre posicionarse como una alternativa correcta y adecuada ante alguna necesidad [the provision of public services does not necessarily generate value, just when it manages to position itself as a proper and adequate alternative to some need]” (López et al., 2018, p. 21).

“En los servicios no hay marcha atrás, son prestaciones que se producen y se consumen en el mismo momento [There is no reverse gear in services, they are produced and consumed at the same time]” (Fernández, 2015, p. 27). Hence the importance of the people who provide the service. The above is complemented by Kotler and Armstrong (2012) when they mention that “service quality will always vary, depending on the interactions between employees and customers” (p. 242), due to its own intangible characteristic and degree of subjectivity.

It follows then that the citizen not only evaluates the final result of a service, but also takes into account the process of receiving it, such as the participation, interest and cordial treatment of the staff, among other factors that are found within the provision of the service (Zeithaml et al., 1993).

It is important to emphasize that organizations require the opinion and suggestions of citizens to measure and optimize internal processes. “El juicio que emite el ciudadano al recibir un bien o servicio es la mayor fuente de información que tiene la organización para mejorar [Judgments made by the citizen when receiving a good or service are the greatest source of information for improving the organization]” (Arrupe & Milito, 2015, p. 189).

Indeed, among the models for evaluating and measuring service quality are the Nordic model, developed by Grönroos in 1984, and SERVQUAL, designed by Parasuraman and other authors in 1985. The former proposes two dimensions: technical quality (what), what the user receives, and functional quality (how) the user receives the service. This model is based “en la brecha existente entre la imagen que el consumidor se crea antes de experimentar el servicio como tal (expectativas), y la imagen que se genera de su experiencia con el servicio (experiencias) [on the gap between the image that the consumer creates before experiencing the service as such (expectations), and the image that is generated from his experience with the service (experiences)]” (Mora, 2011, p. 153).

The second model focuses on processes and strategies to achieve quality service. To measure service quality, the following dimensions were established: trust, reliability, accountability, assurance and tangibility. Quality measurement focuses on the existence of five GAPS (customer and organizational gaps). The midpoint is the customer gap, that is, the difference between customer expectations and perceptions. Therefore, it is important to close organizational gaps to achieve quality (Zeithaml et al., 1993; López et al., 2018).

For its part, the Secretaría de Gestión Pública [Department of Public Management] (SGP), the governing body of the Sistema Administrativo de Modernización del Estado [Administrative System for the Modernization of the State], lists certain elements found in the provision of services that have an impact on user satisfaction: professionalism during service, information, time, management results, accessibility, and trust (PCM, 2021).

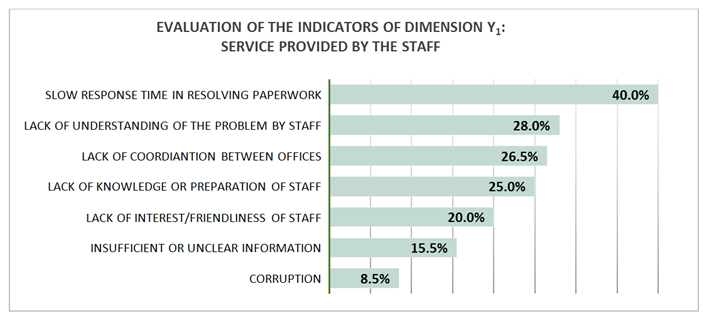

Such elements are generated from citizen perceptions, expressed in the surveys conducted by Ciudadanos al Día (CAD) in 2008, 2010 and 2013. The main deficiencies that citizens experienced during the service provided by the local governments of Lima and Callao were measured in these surveys. Among the items measured were: lack of understanding of the problem by staff, a slow response time in resolving paperwork, lack of coordination between offices and departments, lack of interest/friendliness of staff, insufficient or unclear information, lack of knowledge or preparation of staff, corruption, among other factors (CAD, 2013b; PCM, 2019).

In 2013, CAD conducted a survey in 35 local governments of Lima and Callao to measure corruption, revealing that 3 out of 10 respondents who used the local governments services perceived that they were honest or very honest (CAD, 2013a, p.1). On the other hand, the market researcher IPSOS conducted a nationwide citizen satisfaction survey to evaluate the impact of the performance of various attributes regarding the citizen’s experience in a public entity. Among all of them, “service provided by the staff” was considered as the attribute with the greatest impact on citizen satisfaction in Peru (PCM, 2018).

Based on the analysis of both variables, one can argue that when a citizen establishes contact with a local government, the public servant is the first person with whom he/she communicates; in other words, he/she is the starting and breaking point for providing quality service or not. As communication is bidirectional, it is necessary to build bridges of clear, precise and timely information between local governments, their personnel and the citizen. Hence, it is important that the staff representing a public organization be the best and most qualified (Martínez, 2016).

Likewise, and according to what was expressed by Jhon F. Kennedy “Consumers, by definition, include us all” quoted by Martínez (2016, p. 181). While the citizen is the final beneficiary of public services, they are effectively delivered by the human talent of an organization. For, behind this simile there are processes that are developed “en el marco de una cultura organizacional propia, determinada por la suma de valores, normas y hábitos que son compartidos por las personas y grupos de la organización. Éstas motivan o limitan las prácticas de los agentes y funcionarios [within the framework of an organizational culture of its own, determined by the sum of values, norms and habits commonly shared by the people and groups within the organization. These motivate or limit the practices of agents and officials]” (Arrupe & Milito, 2015, p. 171).

In this process “Existe una alta intervención de factores emocionales. Los estados de ánimo del usuario y del que presta el servicio, influyen sobre el resultado final [There is high involvement of emotional factors. User’s and service provider’s moods influence the final result]” (Fernández, 2015 p. 27). In short, “Es importante reconocer que satisfacer al cliente interno es vital para una empresa saludable; […] la motivación induce a la acción, y esta acción se focaliza en la búsqueda de la satisfacción del cliente externo [It is important to acknowledge that satisfying the internal customer is vital for a healthy company; [...] motivation induces action, and this action is focused on the search for external customer satisfaction]” (Regalado, Allpaca, Baca, & Gerónimo, 2011). Consequently,

como elemento fundamental en el desarrollo asertivo de la organización, la motivación guarda una estrecha relación con la satisfacción laboral, las relaciones laborales y el entorno laboral. Todas las empresas que mantienen un alto grado de motivación en sus empleados también tendrán un alto grado de satisfacción hacia sus clientes [Motivation, as a core element in the assertive development of the organization, is closely related to job satisfaction, labor relations and work environment. All companies that maintain a high degree of motivation in their employees will also have a high degree of customer satisfaction]. (Peña & Villón, 2018, p. 179)

Local governments must be prepared to provide service quality to citizens at all times, by means of trained, motivated and highly ethical personnel. It is necessary to understand that employees have their own personal characteristics (attitudes), abilities and skills (aptitudes), as well as knowledge, which must be reinforced by an organizational culture based on values.

For the contrast of the variables, the main hypothesis was stated: The motivation of human talent is related to citizen service in a local government, Lima 2017. A positive relationship of 0.57 was found.

This research is justified because the findings serve to understand the behavior and the relationship between the motivation of human talent and citizen service. From a human approach, this research has a social and practical relevance, as studying the problem itself and the relationship between its variables is an incentive for organizations to raise awareness and value their staff, which is an absolute cornerstone in any organization to achieve extraordinary results in citizen service. Therefore, this study is a valuable contribution to academia.

As for the limitations found, there is no record of the entity under study having conducted a survey of personnel or citizens that addresses the dimensions and indicators used in this research study.

METHODOLOGY

This research uses a quantitative approach, non-experimental design, cross-sectional correlational, descriptive and deductive method. The research variable “motivation of human talent (X)” is comprised of the intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation dimensions. The variable “citizen service (Y)” is comprised of the service provided by the staff dimension. The population is 3192 people. A probabilistic sample, where everyone has the same chance of being chosen, was used given the nature of the research. Finally, the sample is composed of 343 workers, with a sampling carried out at 95% confidence level and 5% error.

Primary and secondary sources were used for data collection. A five-point Likert scale survey was used as research technique.

Employees were administered the survey during a period of 15 working days in the different local government offices under study. This instrument was prepared based on the objectives of the study and was previously validated by the expert judgment of three specialists in Public Management and Human Resources. IBM's SPSS statistical program, version 25, was used to assess the reliability of the measuring instrument. The internal reliability of the instrument was measured using Cronbach’s alpha, ɑ = 93.6%.

The Spearman correlation coefficient was used to contrast the statistical hypotheses at a confidence level of 95%.

RESULTS

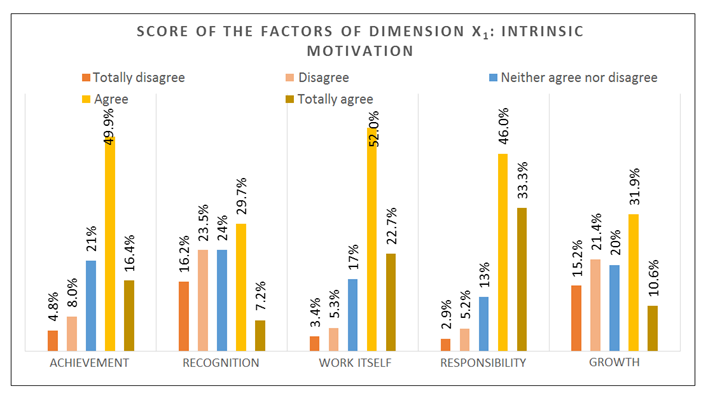

Figure 1 shows the descriptive results of the intrinsic motivation dimension (X1) of the variable motivation of human talent (X). Upon totaling the categories “agree” and “strongly agree”, results are favorable for the factors responsibility with 79.3%, work itself with 74.7%, achievement with 66.3% and growth with 42.5%; however, the factor recognition obtained an unfavorable result with 36.9%.

Source: Prepared by the author.

Figure 1 Score chart of the factors of dimension X1: Intrinsic motivation.

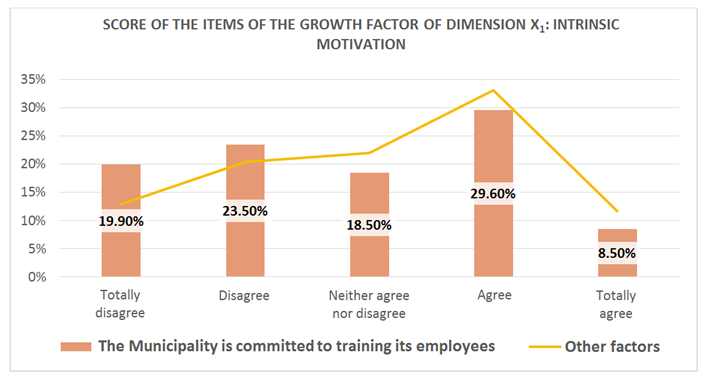

Figure 2 shows only the “growth” factor of the intrinsic motivation dimension (X1). Although the result obtained in this factor was favorable, the item related to training obtained unfavorable results in the categories “disagree” and “strongly disagree” with 43.4%.

Source: Prepared by the author.

Figure 2 Score chart of the items of the growth factor of dimension X1: Intrinsic motivation.

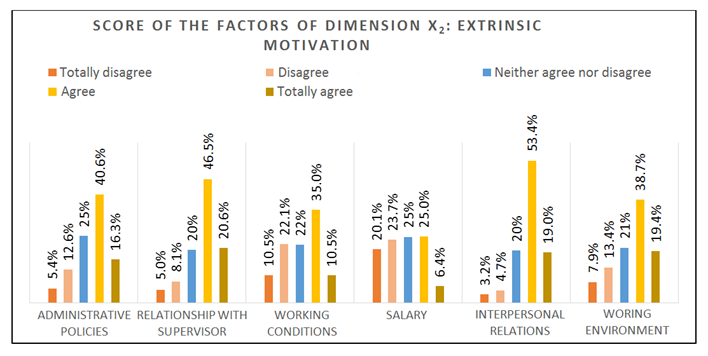

Figure 3 shows the results of the extrinsic motivation dimension (X2) of the variable motivation of human talent. Upon totaling the categories “agree” and “strongly agree”, results are favorable for the factors interpersonal relations with 72.4%, relationship with the supervisor with 67.1%, work environment with 58.1%, working conditions with 45.5% and administrative policies with 56.9%; however, the factor salary obtained an unfavorable result with 43.8%.

Source: Prepared by the author.

Figura 3 Score chart of the factors of dimension X2: Extrinsic motivation.

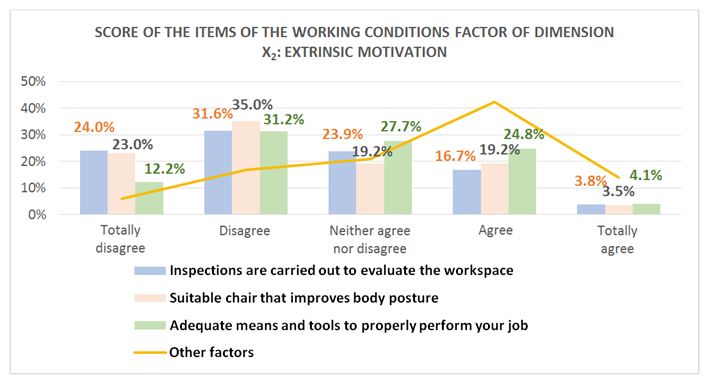

Figure 4 shows the administrative policies factor and Figure 5 shows the working conditions factor, both pertaining to the extrinsic motivation dimension (X2). Their results are favorable; however, some of their items obtained unfavorable results.

Source: Prepared by the author.

Figure 4 Score chart of the items of the administrative policies factor of dimension X2: Extrinsic motivation.

Source: Prepared by the author.

Figure 5 Rating chart of the items of the working conditions factor of dimension X2: Extrinsic motivation.

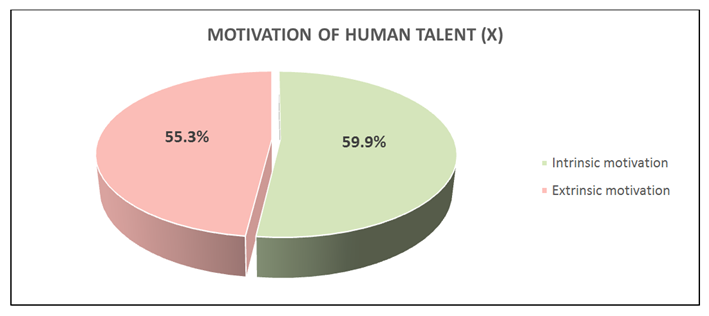

Regarding motivation in general, Figure 6 shows a higher favorable response with respect to intrinsic motivation with 59.9%.

Figure 2 shows that, regarding the intrinsic motivation dimension (X1), 19.9% of the respondents “totally disagreed” with the item related to “training” of the growth factor and 23.5% “disagreed”, which means it obtained an unfavorable result with 43.4%.

In Figure 4, regarding the extrinsic motivation dimension (X2), 10.9% of the respondents “strongly disagreed” with the item on whether the rules and directives of the municipality are respected by its members of the administrative policies factor and 26.4% “disagreed”, which means it obtained an unfavorable result with 37.3%.

Figure 5 shows that, regarding the same dimension with respect to three items of the working conditions factor, 12.2% of the respondents “totally disagreed” with the item adequate means and tools to perform the tasks and 31.2% “disagreed”, which means it obtained an unfavorable result with 43.4%. Some 23.0% of the respondents “strongly disagreed” with the item suitable chair that improves posture and 35.0% “disagreed”, which means it obtained an unfavorable result with 58.0%. Finally, 24.0% “strongly disagreed” with the item inspections to evaluate the workspace and 31.6% “disagreed”, which means it obtained an unfavorable result with 55.6%.

Figure 7 shows that, regarding the service provided by the staff dimension (Y1) of the variable (Y) citizen service, the indicators that stand out negatively are slow response time in resolving paperwork with 40%, followed by lack of understanding of the problem by staff with 28%, lack of coordination between offices with 26.5%, lack of staff knowledge with 25%, lack of interest and friendliness with 20%, insufficient information with 15.5%, and corruption with 8.5%.

Source: Statistical information obtained from PCM, 2018.

Figure 7 Asessment of the indicators of dimension Y1: Service provided by the staff.

HYPOTHESIS TESTING

The testing of the main hypothesis of the variables “motivation of human talent” and “citizen service” yielded the following result:

H1: Motivation of human talent is related to citizen service.

H0: Motivation of human talent is not related to citizen service.

Table 1 shows that there is a moderate positive correlation of 0.57 with a significance level of 0.05 between the variables motivation of human talent (X) and citizen service (Y), in a local government of Lima, 2017.

Table 1 Spearman’s Rho Values for the Variables Motivation of Human Talent and Citizen Service.

| Value | |

|---|---|

| Correlation coefficient | 0.57 |

| N | 343 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.05 |

Source: Prepared by the author.

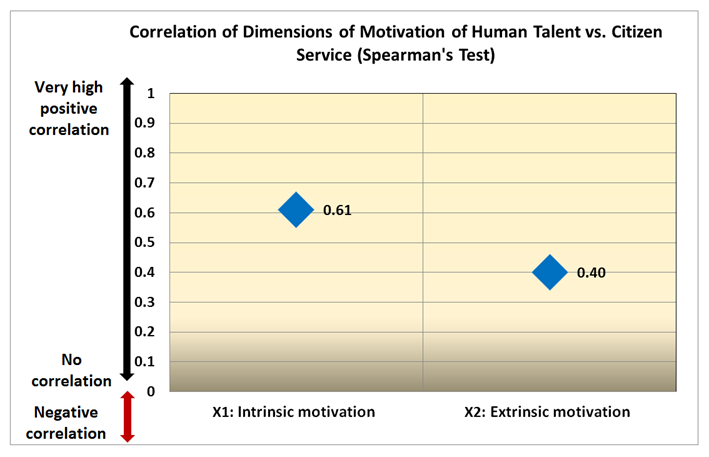

Figure 8 shows a good positive correlation of 0.61 between the intrinsic motivation dimension (X1) and citizen service (Y), subjected to specific hypothesis test 1, with a significance level of 0.05. Likewise, there is a moderate positive correlation of 0.40 between the extrinsic motivation dimension (X2) and citizen service (Y), subjected to specific hypothesis test 2, with a significance level of 0.05.

DISCUSSION

The research findings show that motivation of human talent and citizen service are positively correlated. This is observed in the results obtained in the Encuesta Nacional de Satisfacción Ciudadana 2017 [National Citizen Satisfaction Survey] (PCM, 2018), according to which service provided by the staff is the attribute most valued by citizens in their experience with a public entity. Similarly, the research by Ortiz and Guachamin (2016) evidences that citizen dissatisfaction is attributed to the lack of motivated staff. Meanwhile, in the study of Barrera and Isuiza (2018), taxpayers found that the quality of service was not adequate so they suggested conducting staff motivation workshops. Likewise, Galeano’s (2019) findings prove that citizens are not satisfied with the service provided by the collaborators. For Tonato (2017), human talent management has a very significant impact on the quality of service to citizens.

From the studies, it is evident that citizens feel dissatisfied with the service provided and this is attributed to the lack of motivated staff. Kotler and Armstrong’s (2012) words “service quality depends heavily on the quality of the buyer-seller interaction” (p. 240), which occurs during “la prestación del servicio en donde interactúan con el personal [the provision of the service where they interact with the staff]” (Lovelock & Wirtz, 2009, p. 630) reinforce this statement. Gutiérrez (2014) supports this when he asserts that “los ciudadanos satisfechos requieren de la atención de un personal motivado y satisfecho [satisfied citizens require the assistance of a motivated and satisfied staff]” (p. 56). The relationship between intrinsic motivation and citizen service is significant, considering that the lack of staff recognition has a negative impact on the variable citizen service. The same is also observed in other studies such as those of Ortiz and Guachamin (2016) and Ramírez (2017), in the latter, the staff agrees that recognition is an important factor for their good performance. The person is hence motivated by acts of recognition, not in the sense of gratitude, but rather as confirmation of the fulfillment of a task (Herzberg, 1966), he/she feels valued. Personnel need recognition to build their self-confidence and motivation (Blanchard, Zigami, & Zigami, 2013).

Concerning the relationship between extrinsic motivation and citizen service, weakness is observed in the salary factor, as personnel perceive inequity when compared to that of colleagues who perform the same function. For Herzberg (1966), being this factor within the dimension (X2), it generates dissatisfaction when it is not attended. Thus, as long as there are prohibitions from the central government regarding salary improvements, the entities must find palliatives such as the emotional salary, which has acquired relevance and is highly valued by the workforce (Rojas, 2020). This is stressed by the researcher in quality of life and performance improvement, Jorge Yamamoto, who assures that happiness is linked to productivity in organizations and “propone al bienestar como modelo de responsabilidad social sostenible [proposes well-being as a model of sustainable social responsibility]” (Publimetro, 2015).

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Motivation of human talent and citizen service are positively correlated with a value of 0.57. The findings show that the factors recognition and salary, as well as some indicators of the factors growth, administrative policies and working conditions are unfavorable. It is concluded that a deficient motivation of human talent negatively affects the quality of citizen service. Therefore, it is recommended to design motivation strategies to balance intrinsic and extrinsic factors, develop and implement an internal communication system, form a human quality and citizen service committee to monitor and control compliance with the strategies, commitment and active participation of the mayor, conduct periodic surveys of staff and citizens, and develop an organizational culture based on values.

There is a good positive relationship between the intrinsic motivation dimension and citizen service, with a value of 0.61. The staff members feel motivated in 59.9% and the factors that stand out are responsibility, work itself, achievement and growth; however, the latter reported an unfavorable result in its training indicator (Figure 2). In this dimension, the factor that showed a negative result was recognition. The weaknesses found are related to the unfavorable attributes in citizen service, since intrinsic motivation contributes to the personal and professional growth of the employee and influences his or her behavior and work performance. The design and implementation of training programs on municipal procedures, the use of technological tools and citizen service protocol, reinforcing the practice of empathy, active listening and feedback, is therefore proposed. It is also suggested to develop and implement a program of labor recognition for the effort and performance of the personnel.

Extrinsic motivation and citizen service are positively correlated with a low level of 0.40. The results determined that 55.3% of the staff members is extrinsically motivated by interpersonal relations, relations with the supervisor, work environment, administrative policies and working conditions. However, within the last two factors there are unfavorable indicators that undermine the results. For the first factor, we have the item whether the rules or directives are respected by its members (Figure 4). For the second, there are the items whether the workers have a suitable chair, labor inspections to evaluate the workspace, and work means and tools for the performance of functions (Figure 5). In this dimension, the factor that obtained unfavorable results was salary. It is thus concluded that the findings in dimension (X2) are related to the attributes of citizen service. The importance of this dimension lies in the fact that it is preventive when dealing with optimal factors; otherwise, it generates personnel dissatisfaction and impacts effective citizen service. An emotional salary plan made up of social programs that incorporate the direct family members of the personnel, social volunteer programs in the most vulnerable sectors of a district of Lima, related to the local government under study, should be included in the social welfare program. This in order to develop human sensitivity in the personnel, thereby activating a third motivation: the transcendent one.

Inspections should also be scheduled to evaluate the physical space where personnel carry out their work and provide them with tools for the proper performance of their work. Finally, awareness-raising workshops involving the participation of public staff members and officials should be designed using case studies on the following topics: code of ethics, institutional values, duties and rights of workers, causes and effects of disciplinary processes.

REFERENCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS

Arrupe, G., y Milito, E. (2015). Atención al ciudadano en el ámbito municipal. En M. Pagani, M. Payo y B. Galinelli (Eds.), Estudios sobre Gestión Pública: aportes para la mejora de las organizaciones estatales en el ámbito provincial (págs. 167-191). Buenos Aires, Argentina: Subsecretaría para la Modernización del Estado; Gobierno de la provincia de Buenos Aires. Recuperado de http://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/bitstream/handle/10915/50099/Documento_completo.pdf-PDFA.pdf?sequence=3 [ Links ]

Barrera, A., y Isuiza, M. (2018). Gestión administrativa y calidad de servicio al contribuyente de la Municipalidad Provincial de Alto Amazonas, Loreto 2018. (Tesis de Maestría). Universidad San Martín de Porres, Lima. [ Links ]

Blanchard, K., Zigami, P., y Zigami, D. (2013). Leadership and the One Minute Manager. New York, NY, EE. UU.: HarperCollins. [ Links ]

Bueno, M. (2017). Aristóteles y el ciudadano. Tópicos. Revista De Filosofía, (54), 11-45. Recuperado de https://doi.org/10.21555/top.v0i54.892 [ Links ]

Ciudadanos al Día (CAD). (29 de enero de 2013a). Boletín CAD N° 151 - Corrupción en municipalidades distritales 2013. Recuperado de https://www.ciudadanosaldia.org/publicaciones/boletines-cad/item/551-bolet%C3%ADn-cad-n%C2%B0-151-corrupci%C3%B3n-en-municipalidades-distritales-2013.html [ Links ]

Ciudadanos al Día (CAD). (9 de setiembre de 2013b). Boletín CAD N° 155 - Atención al ciudadano en municipalidades distritales de Lima y Callao 2013. Recuperado de https://www.ciudadanosaldia.org/publicaciones/boletines-cad/item/574-bolet%C3%ADn-cad-n%C2%B0-155-atenci%C3%B3n-al-ciudadano-en-municipalidades-distritales-de-lima-y-callao-2013.html [ Links ]

Corrales, A. (s.f.). Estos son los 5 cambios que propone la Nueva Gestión Pública. Escuela de Posgrado Universidad Continental. Recuperado de https://blogposgrado.ucontinental.edu.pe/estos-son-los-5-cambios-que-propone-la-nueva-gestion-publica [ Links ]

Duque, E. (2005). Revisión del concepto de calidad del servicio y sus modelos de medición. Innovar, revista de ciencias administrativas y sociales 15(25), 64-80. [ Links ]

Fernández, E. (2015). Calidad en atención a usuarios de la administración pública. Recuperado de http://redi.ufasta.edu.ar:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/852 [ Links ]

Galeano, C. (2019). La gestión del talento humano y la calidad de servicios al ciudadano en la Municipalidad Provincial de Huánuco - Período 2019. (Tesis de maestría). Universidad de Huánuco, Huánuco. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez, H. (2014). Calidad y productividad. México D.F., México: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Herzberg, F., Mausner, B., y Bloch, B. (1959). The Motivation to Work. New York, NY, EE.UU.: Wiley. [ Links ]

Herzberg, F. (1966). El Trabajo y la naturaleza del hombre. Barcelona, España: Seix Barral. [ Links ]

Ibáñez, M. (2011). Gestión del talento humano en la Empresa. Lima, Perú: Editorial San Marcos. [ Links ]

Jericó, P. (2008). La nueva gestión del talento humano. Madrid, España: Pearson Educación. [ Links ]

Kotler, P., y Armstrong, G. (2012). Marketing. Estado de México, México: Pearson Educación. [ Links ]

Laveglia, L. (16 de agosto de 2018). ¿Qué es y qué no es la Experiencia del Cliente (CX)? Recuperado de https://www.proaxion.com.ar/post/que-es-la-experiencia-del-cliente-cx [ Links ]

López, L., Olivera, S., y Tinoco, D. (2018). Satisfacción del usuario en el marco de la relación estado-ciudadanos: políticas y estrategias para la calidad de atención al contribuyente en el servicio de administración tributaria. (Tesis de maestría). Universidad ESAN, Lima. Recuperado de https://repositorio.esan.edu.pe/bitstream/handle/20.500.12640/1377/2018_magem_163_04_t.df?sequence=1&isallowed=y [ Links ]

Lovelock, C. y Wirtz, J. (2009). Marketing de servicios. Personal, tecnología y estrategia. Estado de México, México: Pearson Educación. [ Links ]

Manso, J. (2002). El legado de Frederick Irving Herzberg. Revista Universidad EAFIT, 38(128), 79-86. Recuperado de https://publicaciones.eafit.edu.co/index.php/revista-universidad-eafit/article/view/849 [ Links ]

Marsollier, R., y Expósito, C. (2017). Los valores y el compromiso laboral en el empleo público. Revista Empresa y Humanismo, 20(2), 29-50. Recuperado de https://doi.org/10.15581/015.XX.2.29-50 [ Links ]

Martínez, A. (2016). La prestación de los servicios públicos de calidad en el siglo XXI. En M. Romo (Ed.), Una mirada multidisciplinar en relación a la prestación de los servicios públicos (págs.195-234). Quito, Ecuador: Corporación de estudios y publicaciones. [ Links ]

Maslow, A. (1991). Motivación y personalidad. Madrid, España: Ediciones Díaz de Santos. [ Links ]

Matsumoto, R. (2014). Desarrollo del Modelo Servqual para la medición de la calidad del servicio en la empresa de publicidad Ayuda Experto. Perspectivas, (33), 181-209. [ Links ]

Miranda, D. (2016). Motivación Del Talento Humano: La Clave Del Éxito de Una Empresa. Revista Digital Investigación & Negocios, 9(13), 20-27. Recuperado de http://www.scielo.org.bo/pdf/riyn/v9n13/v9n13_a05.pdf [ Links ]

Mora, C. (2011). La calidad del servicio y la satisfacción del consumidor. Revista Brasileira de Marketing, 10(2), 146-162. Recuperado de http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=471747525008 [ Links ]

Newstrom, J. (2011). El comportamiento humano en el trabajo. México D. F., México. McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Ortiz, E., y Guachamin, V. (2016). Modelo de gestión para optimizar el proceso de servicio al cliente en tres sucursales principales del registro civil de la ciudad de Quito, en el período 2014-2015. (Tesis de Maestría). Pontificia Universidad Católica, Ecuador. [ Links ]

Peña, H., y Villón, S. (2018). Motivación Laboral. Elemento Fundamental en el Éxito Organizacional. Revista Scientific, 3(7), 177-192. [ Links ]

Pérez, J., y Merino, M. (2013). Definición de talento. Recuperado de https://definicion.de/talento/ [ Links ]

Presidencia del Consejo de Ministros. (2015). Manual para mejorar la atención a la ciudadanía en las entidades de la administración pública. Recuperado de https://sgp.pcm.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/manual-atencion-ciudadana.pdf [ Links ]

Presidencia del Consejo de Ministros. (2018). Encuesta nacional de satisfacción ciudadana 2017. Recuperado de https://sgp.pcm.gob.pe/noticias/encuesta-nacional-de-satisfaccion-ciudadana-2017-presidencia-del-consejo-de-ministros/ [ Links ]

Presidencia del Consejo de Ministros. (2019). Taller de implementación de la norma técnica para la gestión de la calidad de servicios en el sector público. Recuperado de https://sgp.pcm.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Presentaci%c3%b3n-Taller-Implementaci%c3%b3n.pdf [ Links ]

Presidencia del Consejo de Ministros. (2021). Manual de la norma técnica para la gestión de la calidad de servicios. Recuperado de https://www.gob.pe/institucion/mtpe/informes-publicaciones/1519177-norma-tecnica-para-la-gestion-de-la-calidad-de-servicios [ Links ]

Publimetro. (19 de octubre de 2015). La felicidad, un factor para aumentar la productividad. Recuperado de https://www.publimetro.pe/actualidad/2015/10/19/felicidad-factor-aumentar-productividad-39434-noticia/ [ Links ]

Ramírez, M. (2017). Compromiso organizacional y la motivación laboral en los empleados y obreros de una empresa de servicios de agua potable, Región Callao. (Tesis de Maestría). Universidad Particular Ricardo Palma, Lima. [ Links ]

Regalado, O., Allpacca, R., Baca, L., y Gerónimo, M. (2011). Endomarketing: Estrategias de relación con el cliente interno. Lima, Perú: ESAN ediciones. Recuperado de https://www.esan.edu.pe/publicaciones/serie-gerencia-global/2011/endomarketing-estrategias-de-relacion-con-el-cliente-interno/ [ Links ]

Riding, P. (Productor). (1973). Jumping for the Jelly-beans [Documental]. British Broadcasting Corporation. Recuperado de https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i6gD9ZKiElk&t=84 [ Links ]

Rojas, G. (13 de febrero de 2020). Cuando el salario económico no lo es todo. Conexión esan. Recuperado de https://www.esan.edu.pe/conexion/actualidad/2020/02/13/cuando-el-salario-economico-no-lo-es-todo/ [ Links ]

RSGP N.° 004-2018-PCM/SGP. Aprueban el Nuevo formato del Texto Único de Procedimientos Administrativos. Diario Oficial El Peruano (2018). Recuperado de https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/218679/RSGP_N__004-2018-PCM-SGP.pdf [ Links ]

Schröder, P. (2006). Nueva Gestión Pública: Aportes para el buen gobierno. México D.F., México: Fundación Friedrich Naumann. [ Links ]

Tonato, B. (2017). La calidad del servicio público en el Ecuador: Caso centro de atención universal del IESS del distrito metropolitano de Quito. (Tesis de maestría). Universidad de posgrado del Estado, Quito. [ Links ]

Vaca, M. (2017). Motivación laboral en los servidores públicos de Ecuador. INNOVA Research Journal 2(7):101-108. Recuperado de https://doi.org/10.33890/innova.v2.n7.2017.235 [ Links ]

Yarce, J. (2001). Los valores son una ventaja competitiva: Cómo aprender a practicarlos personalmente. Cómo construir una organización basada en valores. Bogotá, Colombia: Ediciones Instituto Latinoamericano de Liderazgo. [ Links ]

Zeithaml, V., Parasuraman, A., y Berry, L. (1993). Calidad total en la gestión de servicios. Madrid, España: Editorial Díaz de Santos. [ Links ]

Received: August 11, 2021; Accepted: October 11, 2021

texto en

texto en