INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) occupies the first places of incidence and mortality in the world with regional variations and among countries of the same region. The relationship between incidence and mortality of this disease, highlights aspects related to early diagnosis, the quality of preventive plans, and the effectiveness of therapy. While the highest incidence rates occurs in more developed regions (North America, Australasia, and Western Europe), approximately 45% of cases occur in less developed countries 1,2. It is estimated that by the year 2030 it will increase to 2.2 million cases and 1.1 million deaths. In South America there has been a progressive worrisome increase 3.

The purpose of screening is to decrease the risk and mortality from CRC by timely detecting and removing precancerous lesions that have a prolonged period of development during which they can be identified and treated, or even cancerous lesion at an early curable stage.

There are screening guidelines of different quality and with different scopes (global, regional or national) that guide preventive actions using different methods (invasive or not, direct or indirect visualization) and that must be adapted to the available resources 4. Mainly one step pathway (colonoscopy) or two steps including FOBT (Fecal Occult Blood Test) (FIT) as a triage analysis for colonoscopy in those positive 5.

Screening has shown to decrease the incidence and mortality of the disease, although it would not be the only variable that would explain the phenomenon 6-8.

In countries with experience in structured preventive programs, there is a great debate about how to include as many individuals as possible, what is the most costeffective strategy, if it is necessary to decrease the age of onset 9, if it is appropriate to individualize the risk 10,11 establishing whether or not screening is necessary, if is it appropriate to screen patients older than 75 in good health condition and how to achieve a quality colonoscopy since all the guidelines and recommendations state the need for high quality endoscopic studies, as crucial, at the center of the screening 12,13.

The purpose of this review is to describe the characteristics of South America in terms of population, socioeconomics, CRC epidemiology, screening status, and futures challenges.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

A bibliographic review was performed, using Medline platforms, EMBASE (As search terms, we used: occult blood, colorectal cancer and screening) and LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Literature in Health Sciences, with search terms: Screening cancer, early detection of cancer and fecal occult blood).

The search focused on publications originating in the region in the last ten years and was carried out by two independent researchers. Three hundred and eightyseven papers (204 in EMBASE and Medline, 183 in LILACS) were selected initially. Once duplicate papers, reviews, book chapters, cases, and case series were discarded, the abstracts were analyzed to select those related to epidemiology and prevention of CRC.

Finally, a total of 47 publications from the region that met the search criteria, were included.

This process was also validated by the "Ask a librarian" platform of the World Gastroenterology Organization (WGO).

RESULTS

South America is a region that presents particular geographic, demographic, and socioeconomic characteristics that impact its health indicators.

It has more than four hundred million inhabitants distributed in thirteen countries, a region of France and five territories annexed to other states. The region has, on average, around 30 percent of people below the poverty line, a low average Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita and variable development indicator, with slow progression and below most of the countries in North America and Europe.

These conditions are related to the behavior of diseases at the population level, since they determine the characteristics of health systems, their quality and access to care.

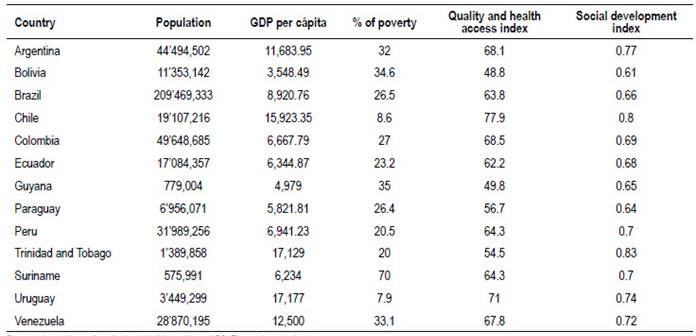

According to socio-economical indexes, our region presents great inequalities (Table 1).

Table 1 South America: Socio-economic and quality data in health.

Sources: https://encovi.ucab.edu.ve/ediciones/encovi-2017/agenda-tematica/

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/ http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/137506#

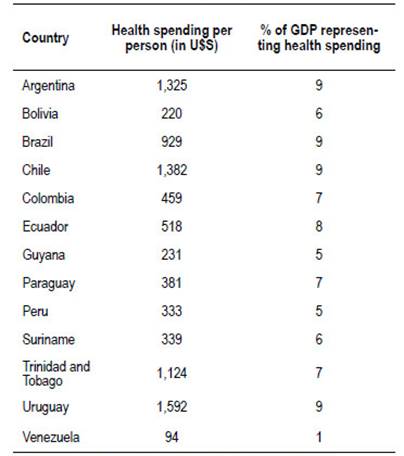

There are structural deficits in the public health system, because of health expenditure per person and the percentage that it represents in GDP (Table 2).

Table 2 South America: Health spending.

Source: World Health Organization. Global Health Expenditure Database.

This context determines fewer amounts of human and technological resources to carry out the screening. For example, in Argentina the number of colonoscopes in the public sector is not enough to carry out a structured preventive program 14. This situation could be similar in other countries in the area.

Social determinants of health and cancer

Prevention of CRC in South America is a challenge where improvement in living conditions is part of disease prevention. For this reason, it is necessary to think about the early detection of CRC at the regional level from a broader perspective that includes the Social Determinants of Health to design better screening programs and more equal approaches 15-17.

The relationship between Social Determinants of Health and cancer is well known. Ethnicity, age, socioeconomical status and social deprivation are related with advanced cancer at the time of diagnosis 18-20.

In individuals with lower SES risk behaviors related to cancer are more frequent 21. The combination of social deprivation, lack of health coverage, risky behaviors and less healthy lifestyle (including lower uptake of screening tests) could explain the differences observed in stage (advanced tumors) and mortality in underserved population 22,23.

Epidemiology

In some countries there is an increase in the incidence of CRC (Colombia, Brazil, Ecuador) 24-27 and mortality and years of life lost (Brazil, Colombia) 28-30. The temporal trend in recent decades shows an increase in comparison with the decrease of other tumors such as the cervix and stomach in Colombia 31.

Higher cancer mortality is observed in indigenous populations 32, older adults, and low socioeconomic strata 33,34.

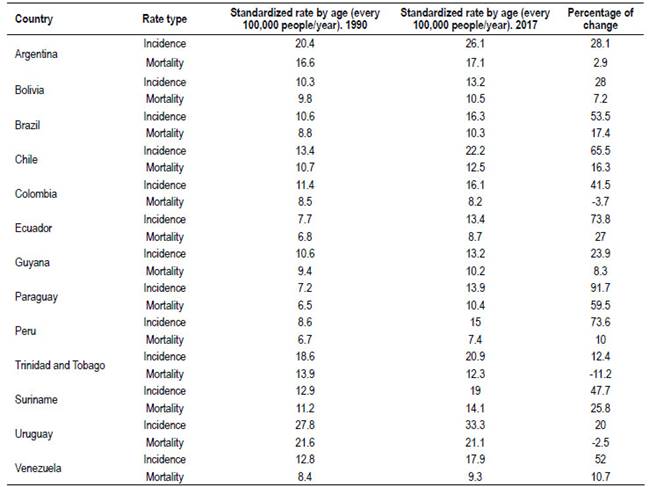

The incidence and mortality are variable, the regional average is below global rates, but there are some countries with rates approaching to the numbers of the countries of Europe, North America and Australasia 35. Countries could be differentiated in high incidence (those cases above the global average, Argentina and Uruguay), countries with average incidence (Chile and Trinidad and Tobago) and the remaining countries with below average incidences (Table 3).

Table 3 South America. Standardized rates of incidence and mortality from CCR.

Source: GBD 2017 Colorectal Cancer Collaborators (2019). The global, regional, and national burden of colorectal cancer and its attributable risk factors in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017.

An evolution and magnitude of the increase according by country between 1990 and 2017 can be seen in Table 3. It is quite clear that the average trend in the incidence is rising.

Interpretation of the data should be carefully afforded. First, the quality of health records in our region has weaknesses. Overall increases in incidence rates are observed with lower percentages of increased mortality, except in three countries: Uruguay, Trinidad and Tobago and Colombia, which show decreasing figures.

The relationship between incidence and mortality may represent (as observed in the temporal analysis of other tumors) the behavior of different variables such as advances in early diagnosis and improvement in treatments. It also could reflect over-diagnosis of a disease (the detection of tumors that do not cause symptoms or death during patient´s lifetime), in CRC. This could be related to an over-diagnosis of polyps or CRC in elderly 36.

The national epidemiological profiles of cancer burden in the study show large heterogeneities, which reflect different exposures to risk factors, economic environments, lifestyles, and access to care and screening 37.

Experiences in screening

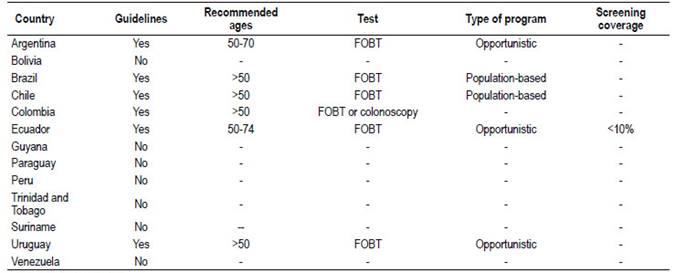

In 2016, the Pan American Health Organization published a report on CRC screening in the Americas (result of an experts meeting); only six countries declared having local screening guides, four population-based programs in pilot experiences (Brazil, Chile, Argentina, and Paraguay) and three opportunistic programs (Ecuador, Trinidad and Tobago, and Uruguay). The rest of the countries declared not having preventive programs 38. There are no structured programmatic plans of national scope (Table 4).

Table 4 Guidelines and CRC screening programs available in South America.

FOBT (Fecal Occult Blood Test)

Source: Pan American Health Organization

There is also regional experience in measures targeting specific high-risk populations such as the implementation of a Registry of Family Polyposis 39, registry of mutations in gastrointestinal cancer, Peutz-Jeghers and management of Lynch Syndrome and hereditary cancer programs 40-44.

Early detection methods

In relation to early detection methods, there is regional evidence in favor of using Fecal Occult Blood Immunochemical Test (FIT) 45-49 combination of FIT and a questionnaire for patients 50 looking for risk criteria, adequate results to perform a cascade method ("two steps") combining FIT and colonoscopy (VCC) 51-53 use of fecal DNA detection for diagnosis of CRC 54 as well as recommendations to perform CRC screening with colonoscopy preferably 55. There are also publications with experiences in VCC 56,57, others related to the quality of colonoscopy 58 and the use of virtual colonoscopy 59,60.

Much of the work is retrospective or descriptive and carried out by private centers, with a variable number of patients and within the framework of opportunistic programs and pilot experiences.

Despite differences in the region's health systems in terms of capacity, human and technological resources, and funding, CRC screening has proven to be cost effective 61.

Most of the pilot experiences developed in the region are based in FOBT, and probably this test could be the best option for population-based programs according the necessity to ensure the access to screening 32.

Barriers

Among the barriers observed for the proper implementation of screening, it is worthy to note the physicians themselves. An Argentinian study observed oversight mistakes in endoscopic follow-up of colonic polyps 62. One from Brazil, shows low adherence to recommendations for colonoscopies in first-degree relatives of patients with CRC 63.

Another barrier is the access to colonoscopy. The delay in performing the colonoscopy after a fecal occult blood test increases the probability of diagnosing diseases that are already malignant and advanced 64.

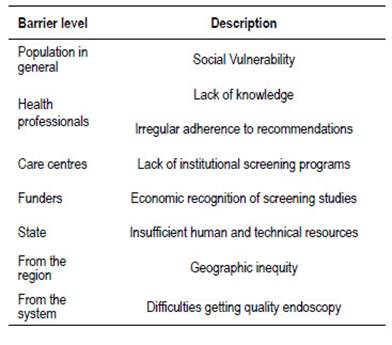

In our region, difficulties in accessing quality endoscopic studies, due to geographic inequities and lack of health coverage, represents an important limitation. An effort should be made to standardize quality criteria in colonoscopy, as a greater effort in equity (Table 5). Sociocultural and educational handicapped populations are less frequently screened (native population, low socio-economic status).

Other barriers observed are lack of knowledge about prevention, fear of adverse effects, and feelings of shame regarding colonoscopy 65-67.

It is important to keep in mind in preventive campaigns, key communication concepts such as confidence in science and technology and the importance of timely detection of the disease in order to achieve a favorable evolution, as well as the need to contemplate the multiculturalism of our region that reflects in different beliefs and attitudes towards the health team 68.

DISCUSSION

The challenge of equity

The great challenge to achieve effective CRC prevention in South America can be summed up in the concept of equity. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines it as the "absence of avoidable or remediable differences between groups of people defined socially, economically, demographically or geographically"69.

It is not enough, then, to provide the same type of resources to all people. First, it is necessary to effectively reach the most vulnerable populations and provide the most effective alternative according to their circumstances (individual risk, availability of resources), improving accessibility. Second, equity involves the concept of quality, that is, the tests should meet standards that allow the best possible results to be obtained.

The evidence shows that FIT should probably be the initial test for structured programs in most of South American countries. The type of FIT (e.g. qualitative vs. quantitative) is a decision that each country should determine based on the local evidence and cost analysis.

The idea of quality is central regardless the screening test used. In the case of colonoscopy, it is key to establish quality as the cornerstone of any program.

Future directions

It is evident that South America is taking its first steps in the prevention of CRC (from pilots to programmatic plans) and that the path must contemplate elements typical of the region in order to achieve the expected results without ignoring the process made by other countries, as well as the scientific evidence.

The socioeconomic and health reality of the subcontinent characterized by inequities of all kinds, determine access to health. So, any policy aimed to reduce poverty and improving medical care will have a positive impact on the evolution of the disease.

A central point in the development of effective screening strategies is to increase research and scientific production on this topic, to better understand the population behavior of CRC, in our countries.

We consider it useful for each country, to evaluate its screening actions taking into account the incidence (high, average or low) to determine if is it convenient to develop structured or opportunistic programs, but always starting from the premise that the awareness of the population is essential.

Two questions must be answered at the local level. What is the starting age of the program? Could it be a strategy to use individual risk (greater than 3%) to start screening? The answer to both questions will depend on the epidemiological data and the human and technical resources available in each country.

One interesting approach to these questions could be, in the future, the concept of precision medicine applied to cancer screening. The combination of molecular knowledge, risk profile and technological advances in early detection oriented to an integrated individualized prevention regimen 70.

The current state of prevention makes necessary the continuity of opportunistic strategies. The education of the health care team is essential as it will allow determining the family risk as well as including the usual recommendation in the medical interview to carry out preventive studies of CRC.

Conclusions

Making CRC screening real in South America requires leadership, creativity, and the ability to craft responses tailored to each local setting.

Sustaining the actions in the long term, measuring results, producing knowledge and developing programs that reduce inequities, raising awareness among the population, educating the health team and ensuring the accessibility and quality of screening methods are concrete steps that will allow us to face this challenge.