1. Introduction6

Globally, journalism is dominated by men, and women vanish (Ibrahim, 2018; Kitch, 2015; Lobo et al., 2017; Ross, 2001; Toff & Palmer, 2019). Indeed, women represent one-third of the world’s journalism workforce (Reuters Institute, 2020). According to the Global Report on the Status of Women in the News Media (2011), 73% of media management positions are filled by men and 27% are filled by women. Regarding professional recognition, of 96 journalists awarded the Pulitzer Prize for the last fifty years, 76 have been men (79%) and 20 have been women (21%) (Enrique, 2014). These numbers show the absence of female professionals in journalism. If the presence of women journalists and sourcesincreased in the media, it would allow them to grow their media power and status (Swers, 2013). In the case of female journalists, they could advance in their professional careers (Hasecke, Scott & Kevin, 2012). In female sources, they would have a voice in media with a position of power, credibility, influence, leadership, and authority (Hasecke, Scott & Kevin, 2012; Leung 1996).

Also, women journalists have to fight against the news subject, because it is associated with gender. In other words, men publish news about politics or economics the hard newsmeanwhile women write news about society or culture the soft news(Armstrong, Boyle, & McLeod, 2012; Easteal et al., 2015; Heldman, Carroll & Olson, 2005; Maras, 2014; Niemi & Pitkänen, 2017; Naylor, 2001; North, 2014; Vos, 2012). The name of this news are euphemisms, and they increase the gender stereotypes, showing women as soft and men as hard (Plakoyiannaki et al., 2008; Tsichla & Zotos, 2016). Where hard is associated with a power position and soft with weak (Van Zoonen, 1995). Of course, this allows male journalists to get in contact with more authoritative sources, benefitting their coverage even more relative to female journalists (Baitinger, 2015; Holmberg & Hellsten, 2015; Ross et al., 2018).

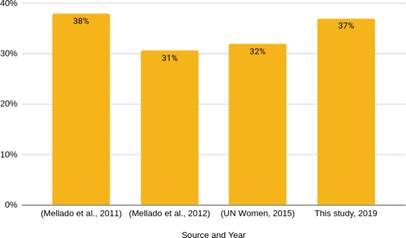

In Chile, the gender ratio of journalists working in the press in 2011 was 62% men versus 38% women (Mellado et al., 2011). Two years later, Mellado (2012) reported 69.4% male and 30.6% female. Three years later, UN Women (2015) found that 68% of Chilean journalists are men and 32% are women. Although previous studies were conducted in Chile between 2010 and 2015, there is no current data about gender -journalist and sourcesin the Chilean press. The lack of updated information is an important problem in Latin America, detected also by Taylor (2012). For that reason, this study wants to update the information and see if the data has changed over the years, comparing the results from 2019 with the ones from 2011, 2012, and 2015 (Mellado et al., 2011; Mellado, 2012; UN Women, 2015). Also, this study wants to analyze the gender of the source. The only study about the gender of the sources in Chile was conducted by UN Women in 2015. The results exposed that 24% of sources were female and 76% were male. The goal of this paper is to update the data from the gender journalist (Mellado, 2012; Mellado et al., 2011; UN Women, 2015), also the gender of the source (UN Women, 2015), and finally, to find new information about the correlation between journalist gender and source gender.

In summary, this article analyzes 12,113 news published by the Chilean press during 2019 to identify their gender as well as the gender of the sources. Further, it examines the relationships between these two variables (journalist gender source gender) to determine if there is a connection between them. Finally, the study identifies the Chilean press who have gender equality in their newsroom and the ones who have not. In this way, this study hopes to expose the role of women as journalists and information sources, given that they do not have the space to be visualized equally.

2. Literature Review

The press has a strong impact on the creation of general attitudes that people hold on issues of gender (Åkerlund, 2019; Bandura & Bryant, 2002; Cha et al., 2012; Jansen et al., 2009; Legge et al., 2018; Vandenberghe 2018). Indeed, through news, journalists can create a social image about gender issues, increasing rejection or respect (Åkerlund 2019; Legge et al., 2018; Wanqi, Caixie & Jiang, 2015). Regarding rejection, the research conducted by Wanqi, Caixie, and Jiang (2015) revealed that Chinese society discriminates against single women since the media generally suggests that these women are responsible for their civil status and that it is their fault that they are not married. Legge et al. (2018) analyzed news from the Canadian press about bisexual women and found that new items increased biphobia through the language used by journalists. In Sweden, Åkerlund (2019) examined news items regarding transsexuality and the data revealed that the press tended to use negative expressions such as “incomprehensible” and “wrong”, increasing rejection of this collective group among the general population. Regarding respect, Hefner et al. (2015) noted that news stories that treated homosexuals in a positive light promoted positive opinions of this group among the general public, whereas those that discussed this group negatively promoted negative public opinions. The goal of these examples about single women, bisexual women, transsexuality, and homosexuality, has been to show the power of the press for creating a public opinion on gender issues. Thus, the social attitudes towards gender themes depend on how the press communicates them (Åkerlund 2019; Garretson 2015; Hefner et al. 2015; Legge et al. 2018; Wangi, Caixi & Jiang 2015). Journalism cannot forget its social responsibility, it means that journalists have to treat people with respect. For that reason, it would be helpful that journalists do a training course about gender studies, especially the ones who are still studying in the universities. This training course would be helpful for journalists inside and outside newsrooms. Inside to be conscious about the gender inequality in the newsroom (Balalaieva, 2019; Gumede, 2020; Lehman-Wilzig & Seletzky, 2010; Ross & Carter, 2011). Outside, with the way that they address the sources according to their gender or sex (Baitinger, 2015; Holmberg & Hellsten, 2015; Macharia, 2015; Vega Montiel & Ortega, 2013).

The declaration from the UN World Conference on Women in Beijing (1995) holds that the press has the power to change social conduct to promote gender equality. However, gender equality is not still reflected in inside or outsidethe newsrooms (Reuters Institute, 2020). If the press has the power to improve society in gender issues, before changing society, the press must change inside. Unfortunately, global data shows that news is dominated by men and the representation of women as journalists make them nearly invisible (Ibrahim, 2018; Kitch, 2015; Lobo et al., 2017; Ross, 2001). In Latin America, women journalists are underrepresented too, there are 29% of female journalists and 71% of male journalists (UN Women, 2015).

2.1. Gender’s Journalists: Who writes the news?

According to the World Economic Forum (WEF), 55% of women are engaged in the labor market as opposed to 78% of men (WEF, 2020b). Also, we are going to need 99.5 years more to be attained gender parity in the workplace (WEF, 2020a). Furthermore, prejudices against women as a professional still dominate workplaces (Moskos, 2019; Verniers & Vala, 2018). Press is no exception. Far fewer women than men serve as reporters and correspondents in the news media and women comprise a minority of newsroom editors and producers (Baitinger, 2015). The reason why there is a minority representation of females in journalism is not clear yet (Hayes, 2011). However, there are some theories. Gender studies suggest that women have been seen in traditional roles such as caretakers and/or exalting their bodies as decorative or sexual objects (Armstrong, Boyle, & McLeod, 2012; Easteal, et al., 2015; Glick & Fiske, 2011; Maras, 2014; Niemi & Pitkänen, 2017; Plakoyiannaki et al., 2008; Tsichla & Zotos, 2016). This has generated some bias against female professional careers, where for men it is difficult to see them as co-workers. For that reason, in the press context, it could lead media professionals-the majority are male-to prefer working with male reporters to female ones (Frederick, 2009; Heldman, Carroll & Olson 2005). In Latin America, qualitative research from Gonem (2013) studied journalistic practices of female professionals in Argentina through deep interviews, she detected that female women have to work in a hostile environment, where they feel excluded through prejudices and disdain from their male colleagues. In Sinaloa (Mexico), with quantitative research Cabanillas and Escalante (2016) examined the vertical barriers inside the newsroom, they found that the representation of women in managerial positions reached 30% and men 70%. In other countries the situation is not better, Balalaieva (2019) analyzed the status of gender imbalance in Ukrainian media, she found that gender stereotypes provoke bias against females’ journalists because males cannot see them outside the social roles. The same results have been found by Rao and Rodny-Gumede (2020). They interviewed female journalists from Indian and South African, the results showed that the newsroom has a strong hegemony masculine culture where women must battle against pre-existing professional stereotypes, especially in their worklife balance. Furthermore, these social stereotypes have led women to often be given the task of writing the soft news while men report the hard news (North, 2014). Soft news is entertainment news focused on human stories, social or cultural events that are connected to emotions and are not considered very prestigious (Lehman-Wilzig & Seletzky, 2010). In contrast, hard news deals with serious stories about important issues, such as politics or economics (Ross & Carter, 2011).

2.2. Gender’s Sources: Who supplies firsthand information?

The traditional roles culturally assigned to women are also repeated in women as sources of information. Villegas (2011) examined the sources of the press in Bolivia, her results confirmed that the news promotes social stereotypes, showing women in traditional roles such as housewife, wife, and girlfriend. In Chile, Hudson (2016), who analyzed the sources of only one newspaper, El Mercurio, found that there is no gender discrimination in the use of sources in that media. Also, Van Zoonen (1995) analyzed media coverage according to gender and his results showed that women were used as sources for news stories related to family contexts and low-status jobs and were portrayed as without authority, without power, passive, emotional, dependent, submissive and indecisive. Correll & Schreiber (1997) found that women are cited as sources more often when the issues at hand are related to abortion or family. In contrast, men are represented as authoritative sources, such as experts, professionals, and workers (Baitinger 2015; Holmberg & Hellsten 2015; Macharia 2015). Vega Montiel & Ortega (2013) found that male sources dominated news stories covering science, economics, or politics. Kitzinger et al. (2008) examined news reports covering scientific topics and found that 84% of the experts cited were men and 16% were women. According to UN Women (2015) globally, 24% of sources cited in news articles are female and 76% are male. Within the Latin American context, articles about sources have been detected in journalism’s papers, but they did not study these sources from a gender perspective. For example, Zunino (2019) examined sources in the digital media in Argentina, one of its results was that they are neither diverse nor plural. This conclusion is similar in Chile, Mellado et al. (2021) found that the use of sources in Chile is associated with political elites, above the observable quota in other Latin American countries such as Mexico or Brazil.

Journalists play a relevant role in choosing their sources because they are offering someone the possibility of having a voice (Cross, 2010; Kruvand, 2012). Kedrowski, Munk, and Leung (1996) defined a source of journalistic interest as one that has an institutional position of power, credibility, influence, leadership, and authority. Therefore, gender equality is important in this context, since those who have a voice will then be related to all these concepts (Allgaier, 2011; Bratton & Kerry, 1999; Conroy, 2018; Lucas, 2017; Niemi & Pitkänen, 2017; Wagner, 2019).

3. Research questions and hypotheses

This study has three research questions: Q1. Who writes the news in the Chilean press according to gender? The gender ratio of journalists working in the Chilean press in 2010 was 62% men versus 38% women (Mellado et al., 2011). Two years later, Mellado (2012) reported 69.4% male and 30.6% female. These data coincide with UN Women (2015), which found that 68% of Chilean journalists are men and 32% are women in 2015. Although previous studies were conducted in Chile between 2010 and 2015, the first research question aims to update this data and see if there is any change. Following these previous studies, our hypothesis will be that men write more news than women in Chile. Q2. Who are the sources, male or female, in the Chilean press? The only study about the sources of gender in Chile was conducted by UN Women in 2015. The results exposed that 24% of sources were female and 76% were male. The goal of the second research question is to confirm or update the data. Therefore, we hypothesize that the results will be close to UN Women. Finally, Q3. Is there a relationship between the gender of journalists and the gender of the sources they cite? No bibliographical reference that addressed this question was detected. With this in mind, the third hypothesis will be that both male and female journalists use more male than female sources.

4. Material and methods

A quantitative method based on a computational social science approach answers the research questions (Watts, 2016). This method combines web scraping and natural language processing techniques to gather and preprocess data, facilitating the exploration of complex social phenomena.

4.1. Gathering news articles from Chilean news media outlets that mention the author’s name

The Directorate of libraries, archives, and museums (DIBAM) of Chile is the organization that registers and inscribes Chilean media content. In 2019 this registry counted 496 media from different channel types (television, radio, print media, online media). Recent studies dealing with online Chilean media content mentioned between 300 and 400 digital news outlets (Vernier, Cárcamo & Scheihing, 2018; Bahamonde et al., 2018). From a list of 400 digital news outlets, the first step consisted of using only the news outlets that mention the name of the journalist who wrote the article. This was done by manually reviewing the latest articles published by each news outlet. Sixteen Chilean digital outlets mentioned the journalist’s name in their articles, while other media did not use the author’s name or use collective authorship. The digital news outlets that met this criterion were 11 national outlets -ADN Radio; Ciper; El Ciudadano; El Dinamo; El Quinto Poder; La Nación; El Desconcierto; Radio Duna; Radio Zero977; El Definido; Pagina7 and 5 regional outlets

Atacama Noticias; BioBio; La Serena Online; El Tipógrafo; La Discusión-. The websites of the news outlets contain internal search engines or a specific structure of pages (for example www. ciper.cl/author/<journalist-name>) that allow searching for the latest articles published by a specific author. We developed an ad-hoc computer script that automatically collects news articles by using crawling and scraping techniques. This script is based on Python open-source libraries. By running the script, the dataset was of 12,113 news written by 158 different journalists.

4.2. Detecting sources using NLP techniques and classifying them according to their gender

In order to answer the research questions, we applied a series of Natural Language Processing techniques to analyze the news articles and to detect which sources are used by the journalists. We used the standard Spanish models of the library spaCy (https://spacy.io/) to tokenize and lemmatize the text of each article and the Named Entities module in order to detect text segments that corresponded to a person’s name. We considered all of the people mentioned by name in the articles as sources that were used by the journalist. The automatic analysis detected 12,334 different sources. Then, the names of both the sources and the journalist(s) were classified by gender using a dictionary of first names. This dictionary contained the 580 most frequent first names found in the Chilean media. At the end of this automatic process, the data was structured into a CSV file (see Table 1). Each line corresponding to a source mentioned by a journalist in a particular article. If a source was repeated itself, it counted only once.

Table 1 Example of how the data is structured in a CSV file to store information about the gender of journalists and sources.

| Outlet name | Url of the article | Journalist’s name | Journalist’s gender | Source’s name | Source’s gender |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pagina7 | www.pagina7.cl/... shtml | Daniela Ramírez | Woman | Armando Agüero | Man |

Source: Own elaboration

5. Results

5.1. Q1: Who writes the news in the Chilean press according to gender?

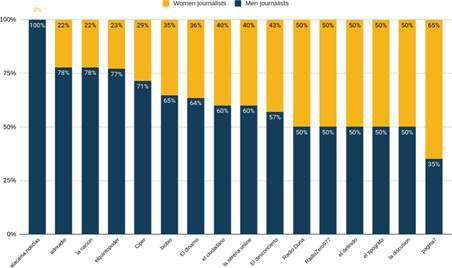

On one hand of the 158 journalists included in our data sample, 99 were men (63%) and 59 were women (37%). On the other hand, of the 12,113 articles gathered in this study, 7,565 (62%) were written by male journalists and 4,548 (38%) by female journalists. These firsts results are close to the ratios obtained by previous studies that were conducted between 2011 and 2015 (Figure 1). The results from 2019 are similar to Mellado et al. (2011) with a difference of 1% fewer women in the newsroom. In 2012 decreased 7% (Mellado et al., 2012) from 2011 (Mellado et al. (2011). In 2015 the ratio of female journalists in Chile grew 1% (UN Women, 2015). Finally, in 2019 the ratio grew again, 5% more.

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 1 Ratio of female journalists at Chilean news outlets according to past and current studies.

In addition, five media from the sample of seventeen had gender equality inside their newsroom: Radio Duna (50% men and 50% women); Radio Zero977 (50% men and 50% women); El Definido (50% men and 50% women); El Tipógrafo (50% men and 50% women) and La Discusión (50% men and 50% women).Ten media had more men than women working on the newsroom: AND Radio (78% male and 22% female); La Nación (78% male and 22% female); El Quinto Poder (77% male and 23% female); Ciper (71% male and 29% female; BioBio (65% male and 35% female); El Dinamo (64% male and 36% female); El Ciudadano (60% male and 40% female); La Serena Online (60% male and 40% female); El Desconcierto (57% male and 43% female). One media Atacama Noticias (100% male and 0% female) did not have female journalists writing news at the moment of the study (see Figure 2). Finally, one media Pagina 7 (35% male and 65% female) had more female than male journalists. The Directorate of libraries, archives, and museums (DIBAM) of Chile is the organization that registers and inscribes Chilean media content. In 2019 this registry counted 496 media from different channel types (television, radio, print media, online media). Recent studies dealing with online Chilean media content mentioned between 300 and 400 digital news outlets (Vernier, Cárcamo & Scheihing, 2018; Bahamonde et al., 2018). From a list of 400 digital news outlets, the first step consisted of using only the news outlets that mention the name of the journalist who wrote the article. This was done by manually reviewing the latest articles published by each news outlet. Sixteen Chilean digital outlets mentioned the journalist’s name in their articles, while other media did not use the author’s name or use collective authorship. The digital news outlets that met this criterion were 11 national outlets -ADN Radio; Ciper; El Ciudadano; El Dinamo; El Quinto Poder; La Nación; El Desconcierto; Radio Duna; Radio Zero977; El Definido; Pagina7 and 5 regional outlets Atacama Noticias; BioBio; La Serena Online; El Tipógrafo; La Discusión-. The websites of the news outlets contain internal search engines or a specific structure of pages (for example www.ciper.cl/author/<journalist-name>) that allow searching for the latest articles published by a specific author. We developed an ad-hoc computer script that automatically collects news articles by using crawling and scraping techniques. This script is based on Python open-source libraries. By running the script, the dataset was of 12,113 news written by 158 different journalists.

5.2. Q2: Who are the sources, male or female, in the Chilean press?

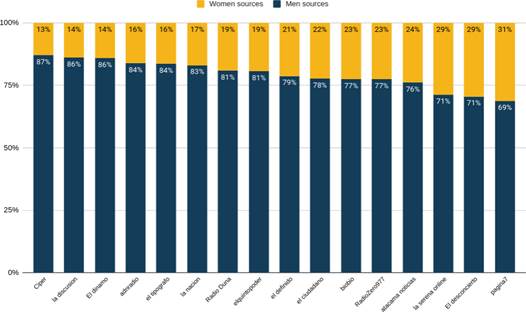

Of the 12,334 sources mentioned in the news, 9,771 were men (79%) and 2,563 were women (21%). This result is quite similar to the 76% of men and 24% of women ratio by UN Women (2015). This show that there has been no significant progress in Chile over the last 5 years using source according to gender. In addition, this ratio was very unbalanced among all Chilean news outlets (see Figure 3). The results from 2019 showed that there is no gender equality in the Chilean press sources. The percentage of male sources is between 80% and 60%. The eighty per cent was found in eight medias: Ciper (87% men 13% women); La Discusión (86% men 14% women); El Dinamo (86% male and 14% female); AND Radio (84% male and 16% female); El Tipógrafo (84% men and 16% women); La Nación (83% male and 17% female); Radio Duna (81% men and 19% women); El Quinto Poder (81% male and 19% female). The seventy per cent was found in seven medias: El Definido (79% men and 21% women); El Ciudadano (78% men and 22% women); BioBio (77% male and 23% female); Radio Zero977 (77% men and 23% women); Atacama Noticias (76% male and 24% female); Serena Online (71% male and 29% female); El Desconcierto (71% male and 29% female). Finally, only one media had sixty percent of male sources and is the only one that is close to getting the gender equality in sources, Pagina 7 (69% male and 31% female).

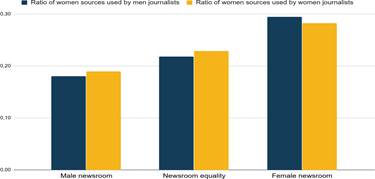

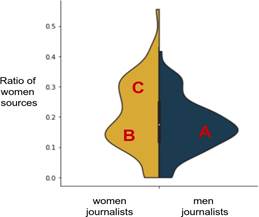

Figure 4 and Table 2 reveals how often the 59 female journalists, and the 99 male journalists cite female sources. The two distribution curves show three trends: (1) male journalists cite women as sources between 10% and 23% of the time (see “A” in Figure 4). Nevertheless, a small group of male journalists cites women as sources around 32%. In contrast, female journalists were divided into two groups (2) those that mention women as sources between 10% and 20% (see “B”), and (3) those that mention women as sources between 25% and 35% of the time (see “C”). Table 2 shows the same distribution of female and male journalists divided in five discrete groups. It underlines that Chilean female journalists tend to cite more women.

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 4 Distribution of female and male journalists according to the ratio of women cited as sources.

Table 2 Distribution of female and male journalists according to the ratio of women cited as sources.

| Año | Fecha | Número de piezas |

|---|---|---|

| 2009 | Jueves, 23 de abril | 8 |

| Lunes, 27 de abril | 4 | |

| 2013 | Jueves, 14 de febrero | 11 |

| Lunes, 18 de febrero | 16 | |

| 2017 | Jueves, 16 de febrero | 12 |

| Lunes, 20 de febrero | 13 | |

| Jueves, 30 de marzo | 6 | |

| Lunes, 3 de abril | 25 | |

| Total | 95 | |

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 4 raises the following sub-question: Why are there two different behavior trends among female journalists (Groups B and C)? Based on additional analyses, we found that the level of equality in the newsroom was related to the behavior of female and male journalists. Figure 5 shows that the ratio of women used as sources increases with the level of equality in the newsroom. On average, the ratio of female sources increased by four points in the more balanced newsrooms and by ten points in the female newsroom. This trend applied to both female and male journalists.

6. Discussion

In May 2018 a feminist movement was born in The Austral University of Chile asking for gender equality in all contexts (Zerán, 2019). It was the first step of more protest against gender inequality in Chile. It means that Chile is worry about these issues. This article wanted to contribute to filling the gender gap in the Chilean press context and be part of the gender equality movement born in 2018. Social changes are not easy. According to Rosabeth Kanter’s Critical Mass Theory, a social group requires a minimum representation of 35% to bring a change (Kanter, 1977). Today the presence of women journalists in the Chilean press stands at 37%, exceeding only 2% of this magic number. However, in 2011 was 38%, in 2012 dropped to 30.6% and in 2015 rose to 32%. It is important to monitor this percentage because it not only reaches 35% but also surpasses it and not down again (as it did between 2012 and 2015).

Men are who write the news and sources are male too. Female sources do not reach 35%, but instead, represent 21% of the sources. Unfortunately, this figure is lower than that determined by the UN Women in 2015, which found that women represented 24% of sources cited. One of the possible reasons for this negative change may be due to the political situation in Chile, where a woman, Michelle Bachelet, was president from 2014 to 2018, and then Sebastían Piñera won the subsequent election. The gender of the president is important given that it is normal that the president of the republic would be, by far, the most referred character in national political news (Wagner, 2019). The use of sources in the media, specifically in the press, gives a connotation of power (Baitinger, 2015; Holmberg & Hellsten, 2015; Kedrowski, Munk & Leung, 1996; Lucas, 2017; Ross et al., 2018; Wagner, 2019). Therefore, if a woman is not considered a source of journalistic interest, she is removed from related concepts, such as influence, leadership, or authority. As Lagarde (2010) stated, it is essential that gender inequality be recognized, because, if the problem is not exposed, it is as if it does not exist. Gender has become a trending topic, but it still does not reflect figures necessary to spur social change. It would be a good starting point, within the journalism schools of universities, to make these results known and to make students aware of the benefits of using more female sources beginning with their first year of studies. Why is gender equality important? For economic and social reasons. Economic because if it were to improve by only 25%, it would increase GDP by $5.3 billion by 2025 (WEF, 2017). Social because, it promotes respect, equity, healthy communities, and non-violence values (Emery & Tian, 2010; Gibson & Steinberg, 2016). Environments without gender equality promote patriarchal rules and emphasize gender stereotype behaviors (Hofstede, 2001; Rovira & Sedano, 2004). Some scholars have already highlighted that an equity work environment promotes creativity, solidarity and improves reputation (Kaur and Singh, 2017; Wilton, et al., 2019). This study has not enough evidence to demonstrate that gender equity in journalists and sources will improve Chilean society. However, as some other authors have already detected an equity gender environment at work means a healthier environment, inside and outside (Hyun, et al., 2016).

This study has analyzed the gender of the journalists and the sources with a quantitative methodology, also it has related two variables (journalist gender source gender). Results show that men and women journalists favor male sources. This behavior can be explained by the fact that male sources are considered powerful sources of information (Holmberg & Hellsten, 2015). In addition, sometimes the stress of work could provoke that journalists cannot find female sources (Niemi & Pitkänen, 2017; Salinas et al., 2015). However, a relevant finding is that women who work in equitable newsrooms, whether consciously or unconsciously, tend to use more female sources. This result coincides with Nicolson’s theory (2015), which states that workspaces with gender equality encourage more egalitarian and respectful thinking. In addition, if a woman has female sources cited in her work, she feels more empowered and less alone (Lewis, 2014). This finding was very important because it allowed us to consider how the organizational culture of the newsroom environment can influence, in some way, the selection of sources and the protagonists of information.

Through a quantitative approach, this study showed that the lack of women in journalism is a pattern that is repeated over the years (2011, 2012, 2015, 2019). In a context of political informacion in the United States, Eric Freedman & Frederick Fico (2005) found that “Female reporters had a greater tendency than their male colleagues to cite female nonpartisan sources”. Evidently, it is not a question of thinking in terms of a quota model, but of highlighting a cultural characteristic that can affect the exercise of journalistic routines. We do not consider proposing a system of quotas, but to account for these patterns in the numerous textual data, allows us to promote reflection among students and trainers of communicators to promote reflection with a sense of equity and work culture of journalistic routines. In addition, there are much more variables than only hiring more women journalists or quoting more female sources. Through a qualitative approach, such as deep interviews, it could be possible to identify horizontal and vertical barriers that women found working inside the Chilean newsroom, such as work environment, work/life imbalance, salary, or promotions. From a methodological point of view, this article has three more additional limitations. First, this study focusses on 16 media outlets 11 national outlets and 5 regional outlets-, which reflect the overall diversity of media in the country. However, it would have been enriching to examine more media. Second, source detection algorithms used on texts always generate an error rate of between 1 and 10%, depending on the quality of the text. But these errors should affect both the female and male genders equally. Third, for this study, we reduced the concept of gender to the names of journalists. However, we are aware that there may be names that do not reflect the current gender of the journalist, e.g., a transsexual who is in the process of changing his or her name. Although this situation does not have a high percentage of probability, it is important to mention it so as not to diminish the importance of this group. Finally, there is a scarcity of academic data related to Latin America (Taylor, 2012). The authors call for researchers to investigate countries in this area of the world so that the data are not so disjointed and are constantly and critically evaluated. Therefore, to be able to reproduce this research in other countries, the algorithm used to scrape and pre-process news stories is available contact authors to get it-.

This research study analyzed news stories published by the Chilean press to identify the gender of journalists and the gender of the sources cited by journalists to determine if there is a connection between these two variables. Through the results of this study, it has been revealed that there is no gender equality in some Chilean media yet. With hope and confidence, in the future maybe we could find more media with gender equality.