The present article tests the hypothesis that patriotism and nationalism are associated with the legitimation of the national social systems. We also explore the role of social status because status groups are differentially motivated to endorse national identification and to perceive the social systems as fair and legitimate given the hierarchical structure of Western societies.

Patriotism, nationalism, and legitimation of the national social systems

Social identity theory (SIT) proposes that people build their identities in reference to the groups they belong, and they intend to achieve a positive individual and collective self-concept (Tajfel, 1974, 1979; Turner et al., 1979). One of the ways individuals accomplish that goal is by categorizing themselves as members of given groups (i.e., in-groups) and by comparing them to other groups (i.e., out-group). The standards used to make these comparisons are highly arbitrary, so usually in-group members choose characteristics that allow them to perceive their in-groups in a better light than out-groups. As a result, people tend to show a preference for members of their in-groups over those belonging to out-groups. This phenomenon has been labelled as in-group bias or in-group favoritism (Brown, 2000). Based on this approach it is not surprising that individuals identify with and show attachment toward their nations.

Psychological and political literature has proposed that national identification is composed of two main dimensions (Bar-Tal, 1993; Kosterman & Feshbach, 1989; Schatz et al., 1999; Sekerdej & Roccas, 2016). The first dimension expresses attachment, positive emotions, and affection toward the national in-group. The second form is focused on a sense of superiority over other countries. Although these types of national identification have received different labels, here we follow the terminology of patriotism and nationalism for referring to the former and the latter dimensions, respectively (Kosterman & Feshbach, 1989).

Based on SIT (Tajfel, 1974, 1979), we expect that both types of national identification will be related to the legitimation of national social systems. When people identify with their national in-group, they perceive it in a positive light because of the pursuit of a positive individual and collective self-concept. In turn, social and political systems represent that in-group in a national context, which might imply that identifying with that in-group will lead to higher perception of legitimacy (Kende et al., 2019; Vargas Salfate et al., 2018). Several studies provide indirect support for this theoretical argument. For example, intergroup contact was associated with legitimation of inequality (Sengupta & Sibley, 2013), making salient national identity (vs. local identity) led to higher system justification (Jasko & Kossowska, 2013), and national identification was associated with system justification in a sample of 19 countries (Vargas Salfate et al., 2018).

Nevertheless, the distinction between nationalism and patriotism allows us to precise the relationship between national identification and legitimation of national social systems. Specifically, we expect a stronger relationship between nationalism and perception of legitimacy than between patriotism and perception of legitimacy. Although both patriotism and nationalism entail national identification, nationalism is also defined by a perception of superiority over other national out-groups (Kosterman & Feshbach, 1989). It implies that nationalism can be less critical toward the national in-group as compared with patriotism, which in turn might explain the pattern of results expected.

Nationalism, patriotism, and social status

National identification, nationalism, and patriotism are not expected to be homogeneous within a given society or national in-group (e.g., Wolak & Dawkins, 2017). Here, we discuss the relevance of social status which has concealed an increasing attention in the legitimation of social systems (e.g., Jost, 2019; Jost et al., 2017; Owuamalam et al., 2019). Because these systems are hierarchically structured not all the in-group members are equally benefited for belonging to a national in-group (Jost & Banaji, 1994; Sidanius & Pratto, 1999, 2004). In addition, the prototypical member of national in-groups usually presents the characteristics of high-status groups (e.g., white, men, etc.; Van Berkelet al., 2017). For that reason, we expect differences in the endorsement of nationalism and patriotism by status groups. Indeed, previous research has showed differences in national identification measures by race (Carter & Perez, 2016) and gender (Van Berkel et al., 2017). Following the same rationale, we also hypothesize a stronger effect of nationalism and patriotism on perception of legitimacy among high-status individuals in coherence with the ideological asymmetry hypothesis (Sidanius et al., 2001).

The present research

In this research, we test the effect of nationalism and patriotism on perception of legitimacy of national social systems in Chile and Peru. Although this association theoretically is straightforward, it has received little attention in applied research. Indeed, most studies have focused on out-group prejudice and discrimination (e.g., Hoyt & Goldin, 2016; Mummendey et al., 2001; Wagner et al., 2012) and on exposure to national symbols (e.g., Butz, 2009; Butz et al., 2007; Sibley et al., 2011). There are several exceptions (e.g., Jasko & Kossowska, 2013; Sengupta & Sibley, 2013; Vargas-Salfate et al., 2018), but none of them have distinguished between nationalism and patriotism. The most important study was conducted by Carter, Ferguson, and Hassin (2011) and showed that implicit nationalism led to system justification using an experimental approach. Nevertheless, they only included a neutral control condition, so we cannot distinguish the unique contribution of nationalism after discarding the shared variance with patriotism.

The present research included as dependent variable system justification and perception of meritocracy. Within system justification theory (Jost & Banaji, 1994), perception of legitimacy has been operationalized through the system justification scale (Kay & Jost, 2003). This measure assesses perception of legitimacy of national social systems, although the items are mainly focused on perception of fairness. In addition, we also included perception of meritocracy in order to provide robust evidence for our hypotheses. The endorsement of meritocracy leads to the perception that the main factor to socially and economically success is individual effort (McCoy & Major, 2008) and is associated with system justification (Son Hing et al., 2011; Wiederkehr et al., 2015). Belief in meritocracy has been theorized as a system justifying ideology within system justification theory because provides a sense of fairness (Jost & Hunyady, 2005). In addition, social dominance theory (Sidanius & Pratto, 2004) has proposed that ideologies such as meritocracy are hierarchy-enhancing myths because promote support for societal inequality.

In summary, based on the above-presented discussion, we will test the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Nationalism and patriotism will be related to legitimation of national social systems.

Hypothesis 2: The relationship between nationalism and legitimation of national social systems will be stronger than the relationship between patriotism and legitimation of national social systems.

Hypothesis 3: The relationship between nationalism and patriotism and legitimation of national social systems will be stronger among high status groups than among low status groups.

Study 1

In Study 1, we test our hypotheses using a Chilean sample. We conducted an on-line survey during April 2018 using an adult convenient sample. In this study, we tested if the endorsement of system justification and perception of meritocracy were predicted by patriotism and nationalism, and if these associations were moderated by social status.

Method

Participants

One hundred and sixty-seven individuals participated in Study 1 (65% women). The mean age was 27.94 (SD = 9.94). Given the presence of missing data in our sample, we performed a Little’s Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test (Little, 1988) using the package BaylorEdPsych (Beaujean, 2015) for R (R Core Team, 2013). For the independent variables, the missing values ranged from 0 to 3 cases, and the test was nonsignificant, (68) = 47.20, p = .974, indicating a random pattern in the missing data. For the dependent variable, the missing data ranged from 0 to 2, and results were similar, with a nonsignificant Little’s MCAR test, (73) = 60.00, p = .863. Based on these results, we imputed data using the stochastic regression method (Baraldi & Enders, 2010) through the Mice package for R (van Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, 2011).

Measures

System Justification. As the first dependent variable, we included the System Justification Scale (Kay & Jost, 2003) using a translated and adapted version for the Chilean context. From a theoretical point of view, this measure assesses general support for status quo and perception of societal fairness (e.g., In general, you find your society to be fair or Everyone has a fair shot at wealth and happiness). All eight items were measured in a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly agree). The scale was highly reliable (α = .82).

Perceived Meritocracy. As the second dependent variable, we included perceived meritocracy. It was measured using a three-item scale developed specifically for the Chilean context (e.g., In Chile people are retributed by their effort; Castillo, Torres, Atria, & Maldonado, 2019). The items were measured using a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). This scale was highly reliable in our sample (α = .77).

Nationalism. As one of the independent variables, we included nationalism using a six-item scale (Kosterman & Feshbach, 1989; Li & Brewer, 2004). This measure was translated and adapted for the Chilean context (e.g., Foreign nations have done some very fine things but it takes Chile to do things in a big way). All items were assessed using a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). We dropped one of the items because of reliability analyses (i.e., It is NOT important that Chile be number one in whatever it does), and we obtained an appropriate measure (α = .72).

Patriotism. As the second independent variable, we included patriotism using a scale developed altogether with the nationalism scale (Kosterman & Feshbach, 1989; Li & Brewer, 2004). We translated and adapted this measure to the Chilean context (e.g., The fact I am Chilean is an important part of my identity) using a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). This measure was highly reliable in our sample (α = .85).

Social Status. As the moderator variable, we included social status. We measured this variable with the item It’s common for groups to be placed in the lowest and the highest levels of our society. Considering this, where would you place yourself? (1 the lowest level to 10 the highest level).

Control variables. As control variables, we included gender (1 = male, 0 = female) and age.

Procedures

Individuals were invited to participate in an online survey about “intergroup relations” in exchange of a retail gift-card. We contacted participants through social networks (Facebook and Twitter) and an email list distribution containing people that had previously participated in unrelated studies conducted by one of the article’s authors. The survey was applied during April 24 to April 27. The questionnaire, first, presented measures about the feminine Chilean football matches (not included in these analyses). Next, we presented nationalism and patriotism measures, and dependent variables randomizing the order for each participant. Finally, demographic measures were included.

Data analysis

We ran a series of linear regression analyses using R (R Core Team, 2013). In these models, we treated system justification and perceived meritocracy as the dependent variables, and nationalism, patriotism, and social status as the independent variables. In addition, we also adjusted by gender and age.

Results and discussion

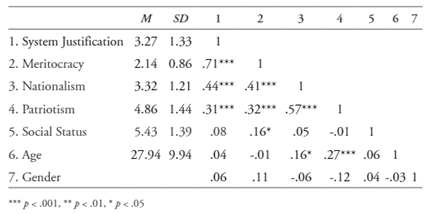

Descriptive statistics and correlations matrix are shown in Table 1. Both nationalism and patriotism were significantly and positively associated with system justification and meritocracy. In addition, nationalism was positively related to patriotism, and system justification to meritocracy. Interestingly, social status was only associated with meritocracy.

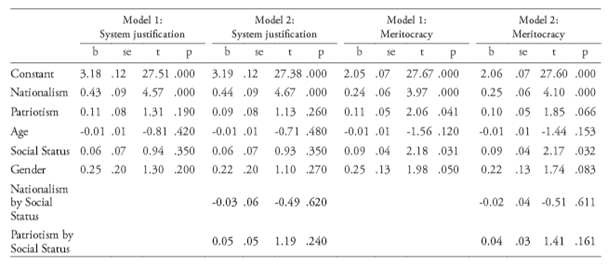

To test our main hypotheses, we conducted a series of linear regressions with system justification and meritocracy as the dependent variables and our continuous predictors grand-mean centered. We also included the interaction terms between social status and both forms of national identification. These analyses are shown in Table 2. When predicting system justification, the model was statistically significant, F (5, 161) = 8.83, p < .001, R 2 = .215, with only nationalism as a significant predictor. The inclusion of the interaction terms led to a significant model, F (7, 159) = 6.49, p < .001, R 2 = .222, but it was not significantly different from the previous regression, F (2, 161) = .71, p = .490 and the interactions were not significant. In other words, only nationalism significantly predicted system justification and this association was not moderated by social status.

The model predicting meritocracy was also significant, F (5, 161) = 9.85, p < .001, R2 = .234, and nationalism, patriotism, and social status were significantly associated with this variable. It is important to mention that the effect of patriotism was significant only at α = .05, meanwhile nationalism was reliable even at α = .001. The inclusion of the interaction terms between social status and both forms of nationalism resulted in a significant model, F (7, 159) = 7.32, p < .001, R 2 = .244, but it did not improve the prediction regarding the previous regression, F (2, 161) = .99, p = .370. In addition, none of these interactions were statistically significant.

Results from Study 1 show support for Hypotheses 1 and 2. In other words, nationalism and patriotism were significantly associated to legitimation of national social systems, when considering system justification and meritocracy. More importantly, when controlling for the shared variance between these two forms of national identification, nationalism was the most reliable predictor of legitimation of national social systems. This is an important finding because based solely on SIT (Tajfel, 1974, 1979) we expected that both forms of national identification would be predictors of legitimacy, but given that nationalism entails a form of superiority over out-group nationalities (Kosterman & Feshbach, 1989) we hypothesized a stronger effect of nationalism.

Surprisingly, we did not observe a significant interaction with social status. Although national identities are hierarchically structured (Carter & Perez, 2016; Van Berkel et al., 2017), the effect of nationalism was homogenous across social status groups. One possible explanation for this divergent result is the low sample size in Study 1. For that reason, we explore our hypotheses in a similar cultural setting (e.g., Peru) using a larger sample in Study 2.

Study 2

In Study 2, we tested our three hypotheses using a Peruvian undergraduate sample. Given the use of correlational data, we also included two theoretically relevant covariates in political psychological literature: social dominance orientation (SDO) and right-wing authoritarianism (RWA). Both are conceived as psychosocial dispositions, but SDO is oriented to support inter-group hierarchies (Sidanius & Pratto, 2004), and RWA is oriented to obedience, social control, and respect for traditions (Altemeyer, 1998). The Dual Process Motivational Model of Ideological Attitudes (Duckitt & Sibley, 2009; Sibley & Duckitt, 2010) proposes that SDO and RWA are moderately correlated, but they have different antecedents and consequences. SDO derives from competitive worldviews and predicts prejudice toward out-groups perceived as a source of competition towards in-groups, meanwhile RWA derives from dangerous worldviews and predicts prejudice toward out-groups perceived as a threat to the social order and traditions. Importantly, both constructs are associated with system justification (e.g., Vargas Salfate et al., 2018) and with nationalism and patriotism (e.g., Osborne et al., 2017). From a theoretical perspective, adjusting for SDO and RWA allows us to identify the specific contribution of nationalism and patriotism on system justification. In other words, we will be able to discard that the relationship between both forms of national identification will not be due to a generalized preference for inter-group hierarchies (i.e., SDO) or a strong general in-group attachment (i.e., RWA).

Method

Participants

Four hundred thirty-two Peruvian undergraduates participated in the study (43.52% women). The mean age was 24.04 (SD = 8.69). We follow the same procedures to handle missing data than in Study 1. For the independent variables, the missing values ranged from 2 to 7 cases, and the test was nonsignificant, (995) = 1026.48, p = .238, indicating a random pattern in the missing cases. For the dependent variables, missing data ranged from 0 to 2, and results were similar, with a nonsignificant Little’s MCAR test, (98) = 111.00, p = .174. Based on these results, we imputed missing data using the stochastic regression method.

Measures

System Justification. As the first dependent variable, we use system justification scale (Kay & Jost, 2003) as in Study 1, but adapted for Peru (Vargas-Salfate, 2019). This measure was highly reliable (α = .71).

Meritocracy. As the second dependent variable we included meritocracy (Zimmermann & Reyna, 2013). This measure contains six items (e.g., People who work hard do achieve success) ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree). This scale was highly reliable (α = .81).

Nationalism. The first independent variable was nationalism. As in Study 1, we used a scale containing six items (Kosterman & Feshbach, 1989; Li & Brewer, 2004) but adapted for the Peruvian context. Even though we excluded the same item than in Study 1, the scale showed a low reliability (α = .51), so results should be cautiously interpreted.

Patriotism. The second independent variable was patriotism, which was measured with the same scale than in Study 1 (Kosterman & Feshbach, 1989; Li & Brewer, 2004) but adapted for the Peruvian context. This measure was highly reliable (α = .75).

Social Status. As in Study 1, the moderator variable was social status. We measured this variable with the item It’s common for groups to be placed in the lowest and the highest levels of our society. Considering this, where would you place yourself? (1 the lowest level to 10 the highest level).

Social Dominance Orientation (SDO). As a covariate, we included the Spanish version of the SDO scale (Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994; Silván-Ferrero & Bustillos, 2007). This scale contains 16 items (e.g., Some are just inferior to others) measured from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree). Scholars have suggested that SDO is composed of two factors: group-based dominance and anti-egalitarianism (Ho et al., 2015, 2012; Jost & Thompson, 2000). We obtained high reliabilities for both factors (α = .72 and .82, respectively).

Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA). As another covariate, we included six items from the Spanish version of the RWA scale (Zakrisson, 2005; Cárdenas & Parra, 2010). The original version of the scale included 12 items (e.g., Our country needs a powerful leader, in order to destroy the radical and immoral current prevailing in society today) ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree). The selected items showed a high reliability (α = .72).

Control variables. As control variables, we included gender (1 = male, 0 = female) and age.

Procedures

Data for this study was collected as part of a broader research on collective rituals and system justifying processes in two waves in a Peruvian undergraduate sample. In this article, we present data from the first wave, which was collected during June 1st to 6th 2018. Authorities from Universidad Continental de Peru sent an email to all undergraduate students asking for their participation in a study about intergroup relationships. The email contained general information about the study and a link to the questionnaire. In the first page, students read and signed an informed consent. Next, all relevant variables in the study were included (i.e., nationalism, patriotism, SDO, RWA, system justification, and meritocracy). Then, the questionnaire also asked about interest and knowledge about football (measures not included in this study). Finally, demographic variables were presented, including the status measures.

Data analysis

We ran a series of linear regression analyses using R (R Core Team, 2013). In these models, we treated system justification and perceived meritocracy as the dependent variables, and nationalism, patriotism, and social status as the independent variables. In addition, we also adjusted by SDO, RWA, gender, and age.

Results and discussion

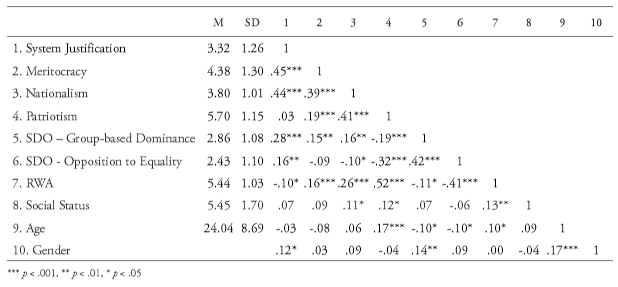

Descriptive statistics and correlations matrix are shown in Table 3. As in Study 1, nationalism was significantly associated with patriotism, and system justification with meritocracy. Nationalism was associated with both system justification and meritocracy, but patriotism was related only to meritocracy. Contrary to previous studies (e.g., Jost & Thompson, 2000), group-based dominance was associated with both forms of legitimation of social systems and opposition to equality only to system justification. Another unexpected result is that RWA was negatively associated with system justification, although its association with meritocracy was positive.

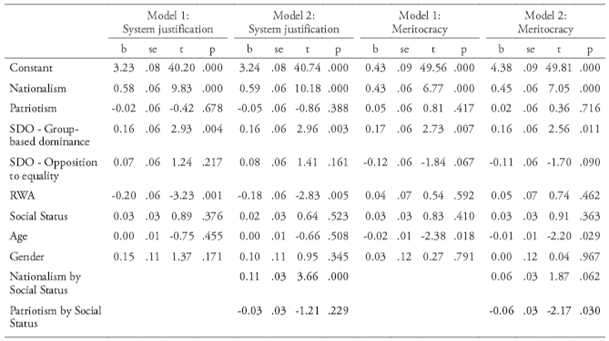

We follow the same data analysis approach than in Study 1 for testing our main hypotheses. The model predicting system justification was statistically significant, F (8, 423) = 20.20, p < .001, R 2 = .276, with nationalism and SDO - group-based dominance as significant and positive predictors, and RWA as a negative predictor. The inclusion of the interaction terms between both forms of national identification and social status led to a significant regression, F (10, 421) = 17.90, p < .001, R 2 = .298, improving the explained variance in comparison with the previous model, F (2, 423) = 6.71, p = .001. Results showed a significant interaction between nationalism and social status. A simple slope analysis (Aiken & West, 1991) revealed that the association between nationalism and system justification was stronger among high status groups (+1 SD, b = .79, s.e. = .08, t = 9.63, p < .001) than among low status groups (-1 SD, b = .40, s.e. = .07, t = 5.38, p < .001).

The model predicting meritocracy was also significant, F (8, 423) = 12.30, p < .001, R 2 = .189. The only significant predictors were nationalism, SDO - group-based dominance, and age. The inclusion of the interaction terms led to a significant model, F (10, 421) = 10.50, p < .001, R 2 = .200, improving the prediction in comparison to the previous model, F (2, 423) = 3.02, p = .050. The interaction between patriotism and social status was significant. A simple slope analysis revealed that patriotism marginally predicted meritocracy among low status groups (SD= -1, b = .13, S.E. = .07, t = 1.76, p = .080) but was not associated among high status groups (SD =1, b = -.08, S.E. = .09, t= -.96, p = .340).

Results from Study 2 provide partial support for our three hypotheses. We found that nationalism and patriotism were significantly associated with meritocracy, but only nationalism was related to system justification. In addition, when controlling for the shared variance between these two constructs, as in Study 1, we found that nationalism was a significant predictor of both forms of legitimation of national social systems. Finally, when predicting system justification, we found that the effect of nationalism was stronger among high status individuals, which is coherent with our theoretical arguments. Given that national identities are hierarchically conceived, with high status groups perceived as more prototypical of their nations (Carter & Perez, 2016; Van Berkel et al., 2017), the effect of endorsing nationalism is more psychologically beneficial for these groups. This might, in turn, motivate high status individuals to perceive the national social systems to which they belong as fair and legitimate.

General Discussion

In this article, we proposed that national identification would be associated with legitimation of national social systems based on the main tenets of SIT (Tajfel, 1974, 1979; Turner et al., 1979). In other words, because of the need to pursuit a positive individual and collective self-concept, national identification would predict support for the national status quo. The literature has proposed that national identification might take different forms such as nationalism and patriotism (Bar-Tal, 1993; Kosterman & Feshbach, 1989; Schatz et al., 1999; Sekerdej & Roccas, 2016). Given that nationalism entails a sense of superiority over other countries, and patriotism is coherent with the possibility of having critical views about the nation, we expected a stronger relationship between nationalism and perception of legitimacy. We tested these hypotheses using an adult Chilean sample and a Peruvian undergraduate sample. Results supported the theoretical assumptions. Specifically, nationalism was a significant predictor of general system justification and meritocracy in both studies. When we included theoretically relevant covariates such as SDO and RWA, we found the same pattern of results in Study 2. More interestingly, patriotism was not a significant predictor in these models, although at a bivariate level was associated with both system justification (Study 1) and meritocracy (Study 1 and 2).

Taken together, these results show that the mere national attachment and affection toward the national in-group does not necessarily lead to supporting the political, economic, and social status quo. Indeed, this attachment in the form of patriotism seems to be coherent with critical views about the in-group. On the other hand, the sense of superiority, which is expressed by nationalism, leads individuals to bolster and justify the status quo. This is one of the main contributions of our article to the literature. To date, most research on national identification and system justification has focused on national identification in the form of superordinate identification (Jasko & Kossowska, 2013; Sengupta & Sibley, 2013; Vargas-Salfate et al., 2018) but without distinguishing between different forms of national identification. Carter et al. (2011) used an experimental approach manipulating nationalism but with only a neutral control condition. This implies that it was not possible to discard the influence of patriotism because of its relationship with nationalism - which in our article is shown in the bivariate correlations. In sum, the distinctive element from national identification that explains system justification is not a general attachment to or love toward the nation but the sense of superiority over other countries.

In addition, we expected differences when comparing individuals from different status groups. Most societies around the world are hierarchically structured so that their members are not equally benefitted (or unbenefited) by belonging to the national in-groups (Jost & Banaji, 1994; Sidanius & Pratto, 1999, 2004). This is also accompanied by a development of national identity based on the characteristics of those groups located at the top of this hierarchy (Devos & Banaji, 2005; Carter & Perez, 2016; Van Berkel et al., 2017). In other words, from an objective point of view, high-status groups are more benefitted by belonging to the national in-group, so they are more prone to support the status quo (Sidanius et al., 2001; Vargas Salfate et al., 2018). In this article, we found only partial support for these predictions. High-status individuals scored higher on patriotism and nationalism and, more importantly, the relationship between nationalism and general system justification was stronger in this group (Study 1). Nevertheless, in Study 1 we did not observe a significant moderation.

Limitations

This article has two main methodological limitations that need to be addressed by future research. First, some of the used measures in this study were not highly valid as we should expect given the suggestion by psychometric literature. Probably, part of this problem is due to the lack of studies developing and validating social justice measures in Spanish (for exceptions see Castillo et al., 2019). This is highly relevant because of the need to ensure that the content of the scales is equivalent across languages and because in Spanish con-trait items are not valid measures of the latent variables intended to measure (for an example see Glick et al., 2000). The second limitation is associated to the use of correlational data. Although results from this study showed a theoretical coherent pattern and we adjusted for several covariates, we can only provide indirect evidence of causal relationships between the variables. Future research should address this issue by the use of experimental designs. Particularly, it is important to include manipulations of both nationalism and patriotism in addition to control conditions in order to completely isolate the effect of each form of national identification.

Future Research

In this article we tested the proposed hypothesis in two particular contexts based on generic arguments derived from SIT. Nevertheless, the process of national identity construction is not isolated from historical, political, economic, cultural and social contexts. This has implications on the specific content that national identification assumes. In that sense, for instance, previous studies have shown that national identification is not always related to prejudice toward immigrants, and this association depends on how the nation definition is conceived (Pehrson et al., 2009; Pehrson et al., 2009). The same argument might be proposed for the study of legitimation of national social systems and its relationship with national identification. Probably, the association between patriotism and support for the status quo might be more prone to be influenced by contextual factors, given that this form of national identification does not contradict the possibility of expressing criticism toward the country or national in-groups.