Introduction

About 11 thousand years ago, during the Neolithic period, humans began the transition from a hunting-gathering lifestyle to farming. Since then, agriculture has been in constant evolution and it is a powerful tool in crop domestication. The great change in agriculture began in the 20th century due to the application of new technologies and tools which allowed for time reduction in the plant breeding process to produce new crop varieties with desirable properties.

Flow cytometry (FCM) is among these new tools used in crop improvement. This technique was developed by Wallace Coulter in the 50s for hematological studies and has been applied since the 80s in plants (Kron et al. 2007). FCM popularity is due to the simplicity to analyze individuals and populations in a short time through the measurement of the light emitted by cells or cellular components in suspension, which are dyed with high specificity fluorochromes to obtain biochemical, biophysical and molecular information of the particles under study (Adan et al. 2017, Kron et al. 2007, Suda & Husband 2007).

The versatility of this technique has enabled the advance in areas such as ecology, systematics, evolutionary biology and plant improvement (Kron et al. 2007). Thus, making the determination of genome size, polyploid detection, cell cycle analysis and plant flow cytogenetics possible (Doležel & Bartoš 2005, Vrana et al. 2016). Because the right plant material was chosen to avoid the existence of secondary metabolites interfering both with the cell staining and with dye fluorescence (Robinson 2019).

Double haploid technique and FCM

Backcrossing is a method to obtain highly homozygous plants but it requires high workforce and is time-consuming (Germaná 2011). Thus, in the 1970s, embryogenesis of gametes was developed to obtain pure lines in shorter periods of time (Castillo et al. 2015, Germanà 2011). This allowed for the development of the double haploid technique and have been applied successfully in Oryza sativa (Guzman & Zapata 2000), Triticum aestivum (Lantos & Pauk 2016, Zheng 2003), Solanum spp. (Tai & Xiong 2013), Capsicum sp. (Ochoa-Alejo 2005), Hordeum vulgare (Szarejko 2013), Zea mays (Barnabás 2003, Zheng et al. 2003), Asparagus officinalis (Shiga et al. 2009) and other 200 species (Forster et al. 2007).

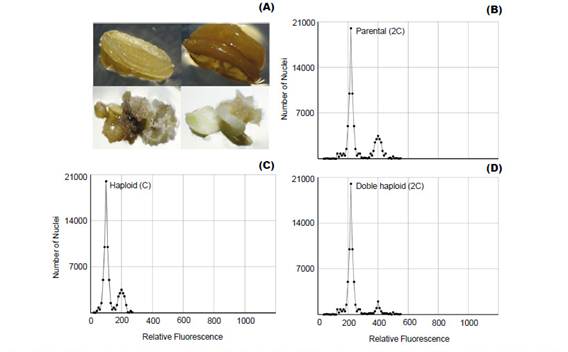

Plant improvement through double-haploid technology makes it possible to obtain thousands of plants that must be properly analyzed, because of ploidy level and haplotype variation among individuals (Zagorska et al. 1997, Seguí-Simarro & Nuez 2007, Perera et al. 2014). Thus, FCM emerges as an effective alternative to determine changes in ploidy (Fig. 1) from suspended nuclei isolated from small amounts of fresh tissue with the help of a hypotonic buffer and treated with a fluorophore with high affinity to DNA (Doležel et al. 2007).

Ploidy level estimation

Polyploid organisms can present more than two chromosomal sets in its nucleus (Soltis et al. 2009, 2007, Münzbergová 2006). This increase in DNA content has boosted biodiversity among plants (Soltis et al. 2009). According to Otto and Whitton (2000) this process has contributed to the speciation of angiosperms (2 - 4%) and ferns (7%). Thus, polyploidization, through the application of achromatic spindle inhibitors (Ramanna & Jacobsen 2003), emerges as an evolutionary mechanism in wild and cultivated plants (Sattler et al. 2015). A polyploid organism can present alterations in the secondary metabolism (Lavania et al. 2012, Wu et al. 2012, Lavania 2005), tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses (Debodt et al. 2005), reproductive alterations (Mable 2003) and morphological changes in roots, leaves, tubers, fruits, flowers and seeds (Tulay & Unal 2010, Wu et al. 2012, Sattler et al. 2015, Baker et al. 2017).

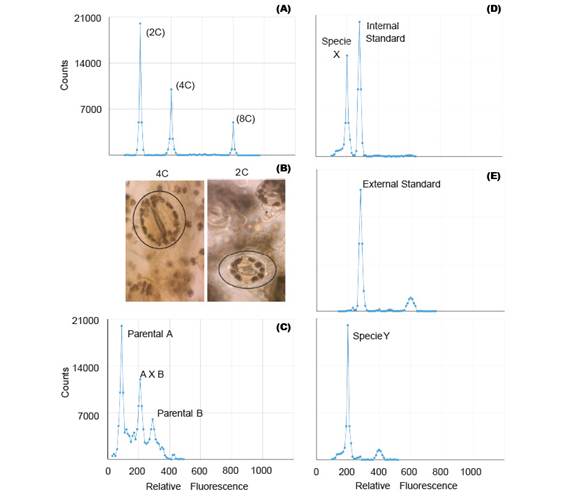

Polyploidization is used by geneticists to shorten the plant breeding process (Lavania 2005) and it have been applied successfully in the genetic improvement of alfalfa, lily, yam, potato, rose, red clover and other species of economic value (Ramanna & Jacobsen 2003). The identification of these polyploids can be done through indirect methods such as determination of the number of chloroplasts and size estimation of the stomata guard cells (Fig. 2B); or direct methods like flow cytometry and cytological counting of chromosome number (Maluszynski et al. 2003). The cytological counting of chromosome number is a very difficult technique, because of chromosome numbers and its size. Thus, FCM has been widely adopted for the determination of ploidy level, because of its high efficiency (Ojiewo et al. 2006), and ability to analyze large amounts of nuclei (Fig. 2A).

FCM analysis of intergeneric and interspecific crosses

Some plant species are often characterized by low levels of genetic variability and can be explained by the domestication process (Ranwez et al. 2017) and/or autogamous mating system (Koelling et al. 2011). This disadvantage can be overcome with the use of techniques aimed to increase the genetic variability, amongst which there are male cytoplasmic sterility, polyploidization, tilling, mutation, bridge crossing, targeted crossing within a species and inter-specific hybrids (Messmer et al. 2015). The early confirmation of these interspecific and intergeneric hybridization, can be detected by FCM (Fig. 2C), because the offspring of these hybrids can be sterile due to genetic and/or chromosomal defects (Stebbins 1958). For instance, Kuwayama et al (2005) evaluated 70 different crosses between Gloriosa spp., Littonia modesta and Sandersonia aurantiaca. He found that the peak position of 5 plantlets derived from the cross between S. aurantiaca and Gloriosa 'Marron Gold' was between parental peaks, which indicated that they were hybrids. Moreover, interspecific hybrids of Fuchsia (Onagraceae) were also detected by FCM (Talluri & Murray 2009).

Genome size estimation

Angiosperms show the greatest diversity and more than 260,000 species are estimated (Soltis & Soltis 2004). This group has a wide variability at the morphological, physiological and genome size (GS). GS is of great interest in taxonomy, evolution and biodiversity research (Pellicer et al. 2018, Bennett & Leitch 2005), because it is able to explain variations in gymnosperms (16 times) and angiosperms (24000 times) (Bennett & Leitch 2011, Pellicer et al. 2018).

In 1976, Bennett and Leitch created the first database on DNA content. Currently, this database (http://data.kew.org/cvalues/) contains data for 8510 plant species. In the database, Paris japonica is the species with the highest DNA content (152.20 pg) and those with the lowest content are Genlisea margaretae and Genlisea aurea with 0.06 pg (Bennett & Leitch 2012). The simplicity of flow cytometry allows for GS evaluation in individuals and populations in a short time. However, this technique requires the use of stable reference standards with known DNA content (Doležel & Bartoš 2005, Praça-Fontes et al. 2011, Doležel et al. 2007). Moreover, it is necessary to evaluate the relative fluorescence of 5000 to 20,000 nuclei for the generation of a good histogram and propidium iodide has to be used for estimation of DNA content in absolute units (Galbraith et al. 1997).

DNA content (sample) = [average value of G1 sample-peak / average value of G1 standard-peak] x standard DNA content (pg)

Genome size analysis requires the use of standards. In analysis with external standards the sample and the standard have to be processed separately (Fig. 2E). While the use of internal standards requires running the sample along with the standard, thus making it more accurate (Fig. 2D). Moreover, despite the use of standards of animal origin in plant research, they are not the most suitable (Doležel et al. 2007).

Conclusion

Peru is a megadiverse country which requires the proper characterization of its genetic resources in order to improve yield in different crops. In this regard due to its versatility and capacity to evaluate large populations, flow cytometry has proven to be a very powerful tool to speed-up selection processes in plant breeding. To achieve the implementation of flow cytometry in Peruvian plant breeding programs, it is required to take into account: 1) How the transport of plant material to the laboratory can affect the analysis 2) the type of explants and 3) the presence of fluorescence inhibitors.

uBio

uBio