Introduction

The Roadside Hawk, Rupornis magnirostris (Gmelin 1788) (Accipitriformes: Accipitridae), occurs from Mexico to Argentina, including Brazil (Santos & Rosado 2009). It is separated into 12 subspecies differing mainly in plumage coloration throughout its range. These birds are diurnal and inhabit a wide variety of environments, including urbanized areas, riverbanks, lakes shores, open fields, forest edges and scrublands, being found up to 3000 m altitude in the Andes. These birds can weigh between 200 and 400 g with males being smaller than females (Sick 1997, Tortato 2009, Barros et al. 2010). The Roadside Hawk lives in pairs and builds nests in the tops of large trees (Sick 1997). In recent decades, this hawk has become more common in urban centers, successfully adapting to this environment. In cities, the supply of prey is greater and natural predators (larger birds of prey) are scarce (Sick 2001, Athiê & Dias 2010, Silva & Machado 2015).

The Roadside Hawk is a generalist, opportunistic predator. Common prey items include small snakes, lizards, large insects, domestic birds and occasionally bats (Santos & Rosado 2009, Sick 1997, Montani et al. 2016, Lima et al. 2020). Tortato (2009) described the predation of Water Opossum, Chironectes minimus (Didelphidae), a small mammal widely found in the Neotropics. The objective of this study was to present a record of the consumption of Coptotermes testaceus (Rhinotermitidae) by Rupornis magnirostris (Accipitridae).

Material and methods

We conducted field observations in the rural area of the municipality of Candeias do Jamari, Rondônia state, Brazil, in the southwestern Brazilian Amazon. The locality comprises a cattle ranch with a pasture area with several isolated Brazil nut trees Bertholletia excelsa (Humboldt & Bonpland) (Lecythidacea). Photographic register was realized with a Nikon P900 camera, lens 24-2000 mm.

Results and discussion

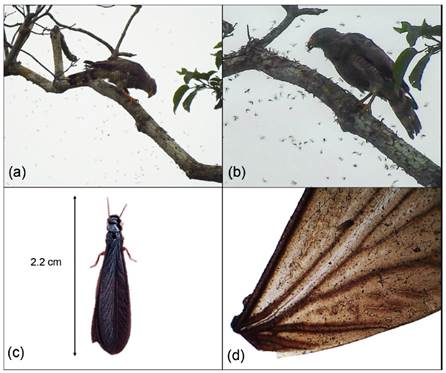

During a general avifauna survey, predation of Coptotermes testaceus (L.) (Blattodea: Rhinotermitidae) alates by an individual R. magnirostris was observed at coordinates 8°44'15.6" S, 63°28'19.7" W, at 08:13 AM on December 6, 2020. The location was along a rural road, in a deforested area. In a Brazil nut tree, Bertholletia excelsa, we noted the opportunistic feeding of an individual R. magnirostris on abundant, swarming alate termites (Fig. 1a, b). The observation was carried about 50 m of distance approximately. The bird remained there consuming the insects for about 25 minutes. After this period, even though there were still individuals of C. testaceus, R. magnirostris left the site. Samples of the winged alate termites were captured and returned to the laboratory. They were determined to be C. testaceus by the wing venation (Scheffrahn et al. 2015). This observation was made during a heavy rainfall. There was a great abundance of C. testaceus alates (Fig. 1c), as under these conditions colonies of this species produce swarms of reproductive for breeding and formation of new colonies.

Figure 1 Photographic evidence of opportunistic predation; a. Rupornis magnirostris; b. Rupornis magnirostris feeding on Coptotermes testaceus alates; c. Coptotermes testaceus; d. Coptotermes testaceus wing under the dissecting microscope (Magnification 10x) for species identification.

Coptotermes testaceus is a xylophagous Neotropical subterranean termite that can be found in both urban and rural environments. It prefers high relative humidity (near 100%) and medium temperatures (20 °C) (Chouvenc et al. 2016, Pozo-Santiago et al. 2020). The swarming of colonies of the family Rhinotermitidae occurs mainly at the end of the dry season and beginning of the rainy season (Medeiros et al. 1999). This swarming is characterized by the appearance of large numbers of winged reproductive and the founding of new colonies (Ferreira et al. 2011). Termites in general are part of the diet of different species of birds (Faria 2007, Fernandes et al. 2007, Vasconcelos et al. 2015), with some species being specialist on certain genera (Vries et al. 2011).

The study by Vasconcelos et al. (2015) on termite consumption by Neotropical birds indicated that only 1.8% of the recorded termites were identified to the species level. There was no mention of termites in the diet of R. magnirostris. Records of the diet composition of R. magnirostris have been mainly documented through opportunistic records (Botero-Delgadillo & Escudero-Páez 2012, Zocche et al. 2018, Lima et al. 2020). In the case of insect consumption records, prey identification has not been possible (Baladrón et al. 2011). Termites are considered agricultural pests (Constantino 2002, Rouland-Lefèvre 2010, Costa et al. 2020) and the use of pesticides for their control can compromise the occurrence and maintenance of this food resource. These factors highlight the importance of this work for understanding the feeding habits of R. magnirostris and the potential importance of C. testaceus and other termite alates in bird diets.

Rupornis magnirostris uses the sit-and-wait technique as its hunting strategy. It typically settles on high perches waiting for its prey (Baladrón et al. 2011). This technique is highly opportunistic (Santos & Rosado 2009). According to Panasci & Whitacre (2000) its main hunting method consists of leaving the perch and to meet the stopped target. It rarely captures birds in flight. In the present report, the bird stayed on the perch and captured the insects with the least energy expenditure possible. This opportunistic feeding was possible due to the momentary availability of large numbers of termite alates in flight. This report documents the opportunistic and generalist feeding behavior of R. magnirostris. The bird took advantage of the presence of a C. testaceus reproductive swarm to feed. This is the first confirmed record of C. testaceus feeding by this bird.

uBio

uBio