Burnout has many different definitions, but it is broadly understood as a long-term product of work-related stress (Maslach & Schaufeli, 1993) characterized by physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion (Schaufeli & Greenglass, 2001). Many human service workers are exposed to burnout, among which domestic violence service providers hold an important risk of developing the syndrome as they constantly interact with victims of violence and their history.

Although we are not aware of any study on burnout on domestic violence helpline services, in general, existent work has focused on burnout in domestic violence shelter staff (Molloy, 2019), domestic violence victim therapists (Ben-Porat & Itzhaky, 2011), sexual assault and domestic violence counselors (Baird & Jenkins, 2003) or social workers (Choi, 2011), among others (Kulkarni et al., 2013). Furthermore, studies on the impact of burnout in domestic violence services is also scarce (Walters et al., 2018).

All around the globe there is a massive pressure on victim support services to provide adequate aid for those affected by abuse; women, children and the elderly are the most prone to experience physical, psychological and sexual abuse (World Health Organization, 2014). Women are especially vulnerable, as one out of three women worldwide have been victims of physical and/or psychological violence at the hands of their partners (World Health Organization, 2013). Given the importance of providing quality services for these populations, we find it important to examine the likelihood of burnout in domestic violence service workers, particularly in countries with high domestic violence rates, which are more likely to have less institutional capacity to address victims’ needs and to properly treat service providers’ burnout. For that reason, it is important to address self-care among these workers since it will also affect positively on the quality of services provided (Gomà-Rodríguez et al., 2018).

Among domestic violence providers, helpline workers face specific risks. Given their work involves listening to stories of violence on a daily basis, in addition to the emotional toll of the work, the stressful context of uncertainty underpinning the psychological support given by these workers is another factor (i.e.: victims could hang up at any moment, his/her aggressor may be meters away, victims may never report to the police). These workers must perform vital services in only a few minutes of telephone communication in which they have to be considerate but are also confronted with difficult situations. In the face of the quarantine response during the COVID-19 context, domestic violence increased in several countries, among others, increasing the demand for helpline services as lockdowns were implemented.

The concept of burnout is broadly assessed by the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), a paid instrument which measures emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and reduced personal accomplishment (Maslach & Jackson, 1981). Although the MBI is the most common burnout inventory used, both its empirical and theoretical dimensions are not free of critiques. The MBI has been criticized for lacking both a strong theoretical conceptualization as well as relationships across its three dimensions. For example, Schaufeli (2003, p. 3) argues that the MBI “[…] has been developed inductively by factor-analyzing a rather arbitrary set of items.” In addition, the MBI has been criticized for having been built without in-depth qualitative research, a problem that may also be related to the difficulty for understanding some of its items originally developed for the Danish society (Yeh et al., 2007).

Other authors have questioned the quality of the relationships across the dimensions. For example, Schaufeli (2003), only considers exhaustion and depersonalization as core dimensions of burnout. On the other hand, Taris et al. (2005), state that depersonalization is usually considered a coping strategy for burnout rather than part of it. In addition, reduced personal accomplishment could be a consequence of burnout that is dependent on personality dispositions or possibly genetics, rather than a fundamental aspect (Shirom, 2005). The MBI is also an incomplete measure of exhaustion as it only focuses on the affective components of emotional exhaustion, leaving aside other sources that also lead to burnout, such as cognitive and physical elements (Halbesleben & Demerouti, 2005).

The extensive use of MBI as a burnout measure has led to a narrowing in its conceptualization (Schaufeli, 2003), by which “…burnout is what the MBI measures and that the MBI measures what burnout is” (Berat et al., 2016). Some scholars claim that the burnout concept of the MBI has been misused in research (Eckleberry-Hunt et al., 2018).

In an effort to fill these gaps in burnout research, Kristensen et al. (2005) developed the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI). It is available in the public domain and is a straightforward measure for burnout in which causal attribution to symptoms is key. It is based on the development of Pines and Aronson (1988) and Shirom (1989), who consider burnout as a state of physical and emotional exhaustion resulting from long-term involvement in emotionally demanding situations at work (cited in Kristensen et al., 2005). For Kristensen et al. (2005), an element of attribution must also be present, and is a fundamental aspect of their definition of burnout: the personal fatigue and exhaustion experienced, the fatigue and exhaustion attributed by the person to work; and the fatigue and exhaustion perceived to be related to working with clients.

Since 2007, the CBI has been validated using several professions and countries and has shown consistent reliability and validity. This literature includes country studies such as: Taiwan (Yeh et al., 2007), New Zealand (Milfont et al., 2008), Portugal and Brazil (Campos et al., 2013; Rocha et al., 2020), Spain (Molinero et al., 2013), Italy (Avanzi et al., 2013; Fiorilli et al., 2015), China (Fong et al., 2014), Thailand (Phuekphan et al., 2016), Serbia (Berat et al., 2016), Iran (Javanshir et al., 2019; Mahmoudi et al., 2017), Malaysia (Chin et al., 2018) and Greece (Papaefstathiou et al., 2019). In general, these studies report good psychometric properties, though mixed results are observed in terms of the number of dimensions since the high correlation between personal and work-related burnout could be interpreted as a single factor (Milfont et al., 2008).

Moreover, despite the important number of CBI validation studies, to our knowledge its psychometric properties have not been assessed in a Spanish-speaking country in Latin America. The only available study that tested the psychometric properties of the CBI in Spanish was developed for Spain (Molinero et al., 2013). Filling this gap would address the need for more international validations in different cultural settings (Kristensen et al., 2005). In that sense, the aim of this study is to adapt and analyze the psychometric properties of the Peruvian version of the CBI. We do so by examining burnout in national domestic violence helpline workers.

The domestic violence helpline service in which we focus our study is the only service of its type in Peru. It is led by the Ministry of Women and Vulnerable Populations. This is a telephone-based free service (24/7) that gives information and orientation for victims of gender-based violence. Approximately, before the pandemics the helpline received ten thousand calls per month. Victims were identified as the partner (42%) - male in most cases - or parent (38%). During pandemics, the volume of calls doubled, but partner violence calls increased slightly their proportion (Author1). No

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from an ongoing longitudinal study on burnout in workers of the national domestic violence helpline in Peru. This study is based on information from 160 participants (mid-June, 2020); 22% of helpline workers decided not to take part in the study. Re-test strategy was also collected a month later (mid-July, 2020). All the participants provided informed consent before completing online protocols.

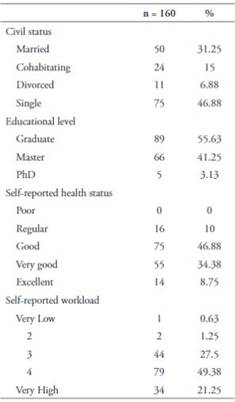

Participants ages ranged between 28 and 61 years old (M = 40.11; SD = 8.19) and 84.38% were women. These professionals were psychologists (58.75%), lawyers (40.00%) or social workers (1.25%). Most of the participants (83.13%) have been working in the service for four or more years. Additional information regarding the sample can be found in Table 1.

Instruments

Information on all instruments was gathered via online questionnaires. Besides instruments presented below, sociodemographic information was also collected (gender, age, marital status, etc.) as well as work characteristics (time working, workload, etc.). These instruments are presented as follows.

Copenhagen Burnout Inventory - CBI (Kristensen et al., 2005). The CBI measures burnout through three scales comprised of 19 items: personal burnout (6 items), work-related burnout (7 items), and client-related burnout (6 items), with scores reflecting an average from each scale. Responses are structured on a 5-point Likert scale (where 5 = always or to a very high degree; 4 = often/to a high degree, 3 = sometimes/somewhat, 2 = seldom/to a low degree, 1 = and never /almost never/to a very low degree). Only item 10 is code-reversed, so that higher values reflect a higher burnout score. The authors suggest rescaling the CBI so it can vary between 0 and 100 (Kristensen et al., 2005).

The original CBI has excellent psychometric properties (Kristensen et al., 2005): internal consistency (coefficient’s alpha: .87 for personal burnout, .87 for work-related burnout, and .85 for client-related burnout) and all correlations between the CBI scales and the Short Form-36 Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36) were found to be statistically significant (p< .001). Validation studies for different cultural settings and professions have confirmed its good psychometric properties (Avanzi et al., 2013; Berat et al., 2016; Campos et al., 2013; Chin et al., 2018; Fiorilli et al., 2015; Fong et al., 2014; Javanshir et al., 2019; Mahmoudi et al., 2017; Milfont et al., 2008; Molinero et al., 2013; Papaefstathiou et al., 2019; Phuekphan et al., 2016; Rocha et al., 2020; Yeh et al., 2007).

Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale - STSS (Moreno-Jiménez et al., 2004). The STSS measures secondary traumatic stress through 14 items comprised of three factors: Emotional fatigue, Cognitive changes, and Symptoms of secondary trauma. It has a 4-point Likert scale (where 1 = strongly disagree and 4 = strongly agree). In this study, the Mexican version was utilized (Meda-Lara et al., 2011). A high coefficient’s alpha was obtained for the overall score (.87) and its factors (.85, .68 and .81, respectively).

Perceived Stress Scale - PSS (S.Cohen et al., 1983). The PSS measures perceived stress through 14 items in a 5-point Likert scale (where 0 = never and 4 = almost always). Items can also be grouped in two dimensions: Positive stress and Negative stress (Guzmán-Yacaman & Reyes-Bossio, 2018). The Peruvian version of this scale was used (Guzmán-Yacaman & Reyes-Bossio, 2018). High internal reliability was obtained for the scale (coefficient’s alpha = .87) and its dimensions (.90 and .75, respectively).

Fear of Covid-19 Scale - FCV-19S (Ahorsu et al., 2020). The FCV-19S measures fear of COVID-19 through 7 items in a 5-point Likert scale (where 1= strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree), with a total score ranging from 7 to 35 points. The Peruvian version was used (Authors). For this study, high internal reliability was found (coefficient’s alpha = .82).

Self-reported health status. Respondents’ perceived health is measured with a single question: “On a scale of 1 to 5, how would you rate your health?”, with responses constructed on a 5-point Likert scale (where 1 = poor and 5 = excellent).

Self-reported workload. Respondents’ perceived workload is measured with the following question: “¿How would you classify an average day’s workload?”, with responses on a 5-point Likert scale (where 1 = very low and 5 = very high).

Procedure

Translation-back translation was applied for the CBI scale. Three psychologists with high proficiency in English translated the CBI independently. One of the psychologists translated the CBI from English to Spanish; then, a second one verified the translation along with two of the coauthors of this study. Later, the verified version was back-translated to English by a third psychologist and checked by the same two co-authors of this study. In the Spanish version used in this study, the term client of the original CBI was replaced by user as it is a more appropriate reference for those who use the service provided by people in our sample and one single Likert scale was employed (5 = always and 1 = never).

Afterwards, the inventory was submitted for evaluation by six judges (all psychologists, four with Master’s degrees and two with Ph.Ds.), who reviewed the scales and made adjustments. Finally, a linguistic pilot evaluation was conducted with three helpline workers (one male and two female), who did not suggest the need for any modification. The final Peruvian version of the CBI can be found in Appendix 1.

Data analysis

Initial descriptive analysis presents mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum values, kurtosis and skewness for the CBI scales and items. Group mean differences are explored by comparing the score of the CBI scales by gender, profession, time working in the service, and workload.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed with Weighted Least Square Mean and Variance Adjusted Estimators (WLSMV) method due to the ordinal nature of the variables (Brown, 2015). To assess the degree to which the data fit the theoretical model, we followed the goodness-of-fit indices and cutoffs suggested by Hu and Bentler (1999), including Chi-Square (non-significant), Root Mean Square Error Approximation and Standardized Root Mean-Square Residual (RMSEA, SRMR < .08), Comparative Fit Index and Tucker-Lewis Index (CFI, TLI >. 90).

Internal consistency was assessed with coefficient alpha for both Trials and Corrected Item-Total Correlation were also analyzed. Due to the limitations of the former (McNeish, 2018), omega coefficient was also used (for Trial 1). This coefficient is more appropriate for non-unidimensional items (Raykov & Marcoulides, 2015). Test-retest was done with a second measurement, gathered a month later. As suggested by Koo & Li (2016), the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was estimated using a two-way mixed-effects model, where an ICC between .5 and .75 is considered moderate reliability (Portney, 2020). We complement information on reliability with Pearson correlations between the CBI scales and across-time correlations for each scale.

Convergent validity evidence was assessed by also estimating the Pearson correlations of the CBI scales with the Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale, the Perceived Stress Scale, and the Fear of Covid-19 Scale. Finally, to obtain test-criterion validity evidence, Pearson correlations were estimated between the CBI scales, self-reported health status and self-reported workload. Cohen’s (1988) criteria for evaluating correlation were taken (small: .10≤ |r| ≤ .3; medium: .3 ≤ |r| ≤ .5; and large: |r| > .5). Data were analyzed using Stata 16 and R Studio version 4.0.3.

Results

Descriptive statistics

In Table 2, descriptive statistics are presented. Participants scored higher on the personal burnout scale (M = 29.69; SD = 14.75), compared to the work-related (M = 27.77; SD = 16.08) and client-related burnout scales (M = 16.07; SD = 13.43). All scales are positively skewed, showing concentration on lower levels of burnout, a result also found in the original CBI validation (Kristensen et al., 2005).

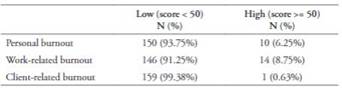

Though no clear cutoffs exist for the CBI, Borritz et al. (2006) suggest considering values equal or above the midpoint of the scale (50) as an indication of a high degree of burnout. Based on this rule, we constructed Table 3. While 6.25% of participants described high personal burnout, the highest concentration of burnout was in the work-related scale (8.75%). In opposition, only one participant presented high levels of burnout related to clients. No participant changed from a non-high score to high level burnout (or vice versa) in Trial 2, suggesting burnout level stability after one month.

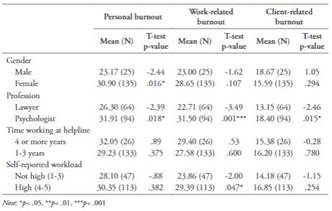

Several group differences were examined to test CBI stability across participant characteristics by difference in means test. As Table 4 illustrates, differences were found only between personal burnout and gender (M men = 23.17, M women = 30.90, t = -2.44, p< .05) and work-related burnout and workload (M not high = 23.86, M high = 29.39, t = -2.00, p<= .05). In all three scales, psychologists experienced more burnout than lawyers.

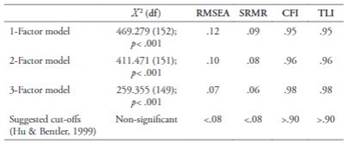

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

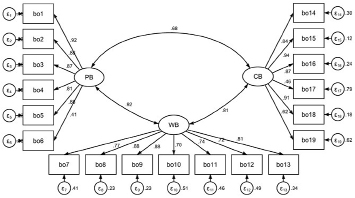

Based on previous research, three models were evaluated: a single-factor model, a two-correlated factor model and the original three-correlated factor model. Since all of them showed significant Chi-squares, other goodness of fit indicators were calculated. Results, presented in Table 5, show that the inclusion of additional correlated factors produces a better fit. The single-factor model only meet CFI and TLI Hu and Bentler’s (1999) cutoff point. The two-correlated factor model, where personal and work-related burnout were considered as a single factor, showed a better performance (RMSEA =.10, SRMR =.08, CFI =.96, TLI =.96), but it was the three-correlated factor model that presented the best fit (RMSEA =.07, SRMR =.06, CFI =.98, TLI =.98).

Table 5 Goodness of fit indices for Confirmatory Factor Analysis-

Note: CFI: Comparative Fit Index; TLI: Tucker-Lewis Index; RMSEA: Root Mean Square Error Approximation; SRMR: Standardized Root Mean-Square Residual.

All items’ factor loadings presented standardized coefficients between .41 and .92 and were statistically significant (p< .001,Figure 1), confirming satisfactory internal validity evidence and a three-correlated factor structure of the CBI as the best solution.

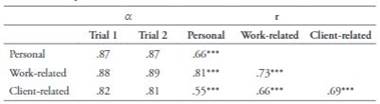

Reliability evidence

Internal consistency was initially examined with Cronbach’s Alpha (Table 6). Coefficients were high for the three CBI scales: .87 (personal burnout), .88 (work-related burnout) and .82 (client-related burnout). Corrected Item-Total Correlation were higher than .30 (personal burnout: .35-.78; work-related burnout: .55-.72; and client-related burnout: .39-.70), which shows appropriate items discrimination. Alpha values for Trial 2 were also high: .87, .89 and .81, respectively.

To avoid relying exclusively on Cronbach’s Alpha, omega coefficient was estimated in Trial 1. We found satisfactory results for all three CBI scales (.92, .92 and .91, respectively). After one month of the initial information collection, test-retest was evaluated by ICC and presented results at an acceptable threshold (>.5): .66 (personal burnout), .73 (work-related burnout) and .69 (client-related burnout).

In addition to reliability evidence, we also estimated Pearson across-time correlations between CBI scales with the second Trial (Table 6), founding strong across-time correlation: .66 for personal burnout, .73 for work-related burnout, and .69 for client-related burnout. Correlations between scales were also large (between .55 and .81).

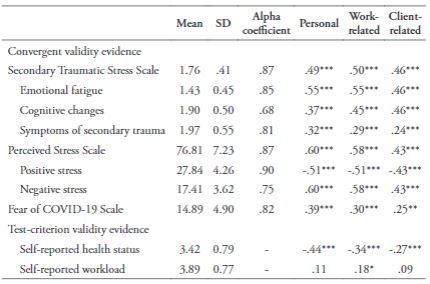

Convergent validity evidence

To assess convergent validity evidence, we explored the Pearson correlation between CBI scales and other related constructs. Results are presented in Table 7. The Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale was positively and moderately correlated with personal burnout (r=.49, p< .001), work-related burnout (r=.50, p< .001) and client-related burnout (r=.46, p< .001). The Emotional Fatigue scale of the Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale was strongly associated with personal burnout and work-related burnout (r=.55, p < .001).

With respect to the Perceived Stress Scale, the strongest correlation was with personal burnout (r= .60, p< .001). At the dimension level, both positive and negative stress were highly correlated with personal and work-related burnout, but the association was stronger with negative stress (r=.60 and .58, p< .001, respectively).

Due to the current pandemic context, we examined the correlation between the CBI and the Fear of Covid-19 Scale, finding moderate and statistically significant positive correlations with the three scales: r= .39 (personal burnout), p< .001; r=.30 (work-related burnout), p< .001; and r=.25 (client-related burnout), p< .01.

Test-criterion validity evidence

As hypothesized, the CBI scales showed negative correlations with self-reported health: r= -.44 (personal burnout), p< .001; r= -.34 (work-related burnout), p< .001; and r= -.27 (client-related burnout); p< .001. Work-related burnout was the only scale that was significantly and positively associated with self-reported workload (r= .18, p< .05).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to adapt and validate a Peruvian version of the CBI in workers of the national domestic violence helpline in Peru. For that purpose, psychometric properties were evaluated, finding adequate validity and reliability evidence.

Regarding the internal structure of the CBI, we tested a one-, two- and three- correlated factor model, following previous mixed results (Grigorescu et al., 2018; Milfont et al., 2008). The three-correlated factor model, also theoretically justified, performed better in all goodness of fit indices. In this model, standardized factor loadings varied between .41 and .94. Our results are in line with Grigorescu et al. (2018), who also tested a CFA with two and three factors and found that the three factor solution produced the best fit.

Regarding internal reliability, high coefficient’s alpha were obtained for the CBI scales (.87, .88 and .82), with similar values to the original CBI study (Kristensen et al., 2005). Also, the personal burnout alpha coefficient was slightly higher than the client-related dimension, as other validation studies have found (Avanzi et al., 2013; Chin et al., 2018; Fiorilli et al., 2015; Fong et al., 2014; Javanshir et al., 2019; Kristensen et al., 2005; Mahmoudi et al., 2017; Milfont et al., 2008; Molinero et al., 2013; Phuekphan et al., 2016). Omega coefficient were also satisfactory for the three scales. Moreover, test-retest reliability was also acceptable. All this information suggests that the Peruvian version of the CBI presents good internal consistency and stability over time.

High correlation was observed between personal burnout and work-related burnout scales, which have also been found in previous validation studies (Avanzi et al., 2013; Campos et al., 2013; Chin et al., 2018; Fiorilli et al., 2015; Fong et al., 2014; Milfont et al., 2008; Molinero et al., 2013; Rocha et al., 2020; Yeh et al., 2007). This result has been interpreted as due to the difficulty to differentiate personal from work-related burnout, as for many people, work may be a central part of life (Fong et al., 2014; Rocha et al., 2020; Yeh et al., 2007). In addition to the above, high correlation between all three CBI scales could be due to the characteristics of our sample as well as the current COVID-19 crisis, where changes regarding the way of working have occurred. Teleworking from home has supposed a major challenge when setting limits between personal and working sphere (Hayter, 2020; Instituto Peruano de Economía -IPE, 2020), considering that currently many activities of both spaces share the same time and physical space. Moreover, people did not have the opportunity to prepare in advance for this scenario and many of them may not have the implements or an environment to work from home (International Labour Organization -ILO, 2020; Organización Internacional del Trabajo-OIT, 2019). This could also explain the average scores found in this study (personal burnout = 29.69, work-related burnout = 27.77, and client-related burnout= 16.07).

Personal burnout proved to be higher among women, work-related burnout was highest among those with a high workload and differences were found for all CBI scales and profession. Previous studies shed light on the interpretation of these findings. Wood et al. (2020) states that female and non-binary individuals, as well as younger workers, experience higher levels of burnout, which may be due to work-life imbalances associated with gender disparity (Sestili et al., 2018; Wood et al., 2020). In that regard, Hämmig (2018) has also acknowledged work-life imbalance as a predictor of burnout. However, it is also possible that the higher burnout in women in our sample could be explained by the gendered nature of domestic violence and the possibility that women are more likely to accumulate higher stress in this environment. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated gender gaps, making women particularly more prone to experience higher levels of stress-, anxiety- and depression-related to work (Health and Safety Executive -HSE, 2020), which could be explained by women perceiving greater amount of work when working from home as they may carry more responsibilities than their male peers, which coincides with the fact that women report greater fatigue (Del Río & García, 2020).

The CBI scales presented moderate to high positive correlations with the Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale and the Perceived Stress Scale, having found a stronger association with the Emotional fatigue and Negative stress sub-scales, respectively. These results confirm the convergent validity evidence for the CBI. In this regard, other validation studies have demonstrated that the CBI is also related to similar constructs, such as depression (Campos et al., 2013), anxiety (Fong et al., 2014) and quality of life (Kristensen et al., 2005; Molinero et al., 2013; Yeh et al., 2007).

As the study was developed during the COVID-19 pandemic, new and additional stressors may have appeared. In that sense, we examined the correlation between the CBI and the Fear of COVID-19 Scale. A moderate correlation was found between the latter and each CBI scale. This association suggests that even though the burnout concept implies a long-term involvement in emotionally demanding situations at work, new stressful conditions may play a certain role in exhaustion and fatigue, particularly that attributed to work and perceived to be related to clients. We suspect two factors drive this result. First, since the first quarantine adopted in Peru, the workers included in this study started to work remotely (from home), which may have blurred the lines between burnout originated at work and changing household dynamics due to health and social isolation measures. Second, as Kristensen et al. (2005) previously indicated, burnout could be altered systematically over time by new contexts. Future research should examine evidence to clarify whether burnout is a cause or effect of fear of COVID-19, or if they have a comorbid relationship. In any case, our study is the first to raise the relationship between burnout as a long-term consequence and fear of COVID-19 as a temporary global threat.

Regarding test-criterion validity evidence, these results indicate that those with higher burnout are likely to have poorer health status and tend to perceive a more intense daily workload. The relationship between burnout and workload has previously been found (Crowe et al., 2018). For example, Xiaoming et al. (2014) found that the amount of workload predicts burnout in medical staff.

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, working conditions may include high risk of fatigue and exhaustion, one that may be even more likely in the domestic violence service sector. To that extent, the prevalent rates of domestic violence in some countries exacerbate risks of burnout. Tools for correctly identify stressors and burnout conditions are important as they provide the basic information for possible treatments and public policy alternatives. These results could contribute to that first step, as the CBI Scale could facilitate the development of a burnout research agenda in Peru. Future studies could use this contextualized scale to examine factors such as work-life balance, coping strategies, burnout prevention, work engagement, sick days, and intention to leave work, among others. To our knowledge, this is the first study to validate the CBI scale in Spanish in the Latin American context and could contribute in an important way to the study of burnout on the continent.

Regarding the limitations of this study, given that a small sample was used, we cannot engage in generalizations as regards the Peruvian population given problems of power analysis. Following prior studies, the Peruvian version of the CBI would benefit from establishing convergent validity with the MBI (Campos et al., 2013; Fiorzilli et al., 2015; Jacobs et al., 2012; Winwood & Winefield, 2004) or other related constructs, such as depression or anxiety (Campos et al., 2013; Fong et al., 2014) and work-related constructs (Berat et al., 2016; Fiorilli et al., 2015; Leake et al., 2017; Molinero et al., 2013; Yeh et al., 2007). Also, further analyses should examine evidence for discriminant validity, such as measures of well-being (Avanzi et al., 2013; Fong et al., 2014; Kristensen et al., 2005; Lyndon et al., 2017; Milfont et al., 2008; Molinero et al., 2013; Sestili et al., 2018; Yeh et al., 2007).

In conclusion, the Peruvian version of the CBI has demonstrated to have good reliability and validity evidence making it an appropriate tool to evaluate burnout related to, in this case, domestic violence service workers.