INTRODUCTION

Follicular gastritis (FG) consists of a particular chronic persistent inflammatory process, which is preceded by Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection 1,2. These bacteria are estimated to have infected more than 50% of the global population 3-6. Likewise, it has been proposed that the acquisition and colonization of H. pylori begin in childhood and are established as a chronic infection. This triggers perpetual and progressive gastric inflammation, leading to clinical complications in about 1-10% of patients 7,8. In this sense, H. pylori has been associated with diseases such as peptic ulcer, atrophic gastritis, intestinal gastritis, gastric cancer, and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (MALT) 1,8. In addition, the International Agency for Research on Cancer 9 of the World Health Organization (WHO) has classified it as a type I carcinogen 10. It is also worth mentioning that H. pylori infection has been included as an infectious disease in the update of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) 11. Therefore, all infected patients must receive adequate treatment, generating a paradigm shift since treatment is no longer only reserved for patients with clinical manifestations of infection 12.

Although some studies associate H. pylori infection with FG 13-19, a high prevalence of gastric MALT lymphoma has also been observed in patients without H. pylori infection20; Therefore, its role in the FG progression to MALT lymphoma has not yet been completely clarified. Given this scenario, an enormous interest and research on H. pylori infection has been aroused, primarily motivated by the need to reexamine this problem and elucidate the pathogenic mechanisms involved, the multiple conditions associated with the bacteria, virulence factors, and the heterogeneity of the disease. Therefore, it is pertinent to carry out this Article Review that aims to expose the critical role that H. pylori play in the development of FG, the histopathological findings, etiopathogenesis, and diagnostic methods to provide a comprehensive overview of FG. Therefore, we suggest implementing strategies such as monitoring, and H. pylori eradication for the treatment of FG.

Definition

FG is a particular type of chronic gastritis characterized by the presence of a mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate and the formation of lymphoid follicles with a germinal center 21,22. Although several studies have made a closer approximation of the macroscopic findings of FG, the microscopic definition is not well-established 23. This limitation has led to the lack of an acceptable definition of histopathological findings. Therefore, the use of confusing definitions and the absence of standardization between studies has made it difficult to establish the cause-effect relationship and delay the diagnosis 23. At least, for most relevant studies, FG is characterized by follicular lymphoid hyperplasia of lymphoid nodules with intraepithelial lymphocytosis 23. In Eastern countries, the definition is more rigorous, which includes the identification of at least two secondary lymphoid follicles in an area of 1 cm of gastric mucosa in the lesser curvature of the antrum 14. This definition is compatible with the premise that the antral mucosa is the most common location where lymphoid follicles are found. It is necessary to specify that the presence of the germinal center differentiates FG from lymphoid aggregates. In addition, there are multiple descriptions in the literature of the disease, such as follicular lymphoid hyperplasia, pseudolymphoma, nodular gastritis, nodular antritis, and lymphofollicular gastritis.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of H. pylori infection varies worldwide; it ranges between 19% and 88%, mainly influenced by socioeconomic conditions, geographical location, age, and hygiene conditions 3,24,25. Regarding the prevalence of FG, there is dissimilar data across different countries. Miyamoto et al.15, reported in Japan, a prevalence of 0.2%. Data provided by Greek and French researchers show a prevalence of 13% and 14%, respectively 26. Unlike Korea, a study reveals a prevalence of 51% 27. In similar studies, prevalences have been shown to range between 27% and 80% 28-31. While other authors have estimated a prevalence of 0.7%-2.9% 15,32-34.

In Colombia, a study carried out by Martínez-Henao et al. determined a prevalence of 8.4% 35. In the recent study by Melo-Peñaloza et al.36, a FG prevalence rate of 34% was reported in patients with H. pylori infection and 10% without H. pylori infection. These heterogeneous data are likely explained by the histopathological definition, the number of gastric biopsies taken in the studies, and the site from which the was collected 31. Therefore, an underdiagnosis of FG has been related to an insufficient number or inappropriate site of gastric samples, given that lymphoid follicles are greater by up to 44% when samples are taken from the antral mucosa compared to the findings from the body mucosa 29,37. Additionally, the definition of FG in some studies does not discriminate between lymphoid aggregates and lymphoid follicles with a germinal center, the latter being the histopathological condition that defines the diagnosis of FG 21-23.

Risk factors

In the risk factors for FG, a higher frequency has been determined in pediatric patients with persistent symptoms of dyspepsia, while in females; apparently, there is a particular risk for the development of this condition 17,18,22,37-42. The higher incidence of functional dyspepsia in females suggests a hormonal influence on the development of the condition despite the prevalent H. pylori infection in both genders. However, this pattern has not been consistently observed in Colombia 35. Additionally, age and sex are not the sole predisposing factors for the development of FG. This condition has been observed more frequently in patients with other states related to H. pylori infection, such as gastric ulcers. Furthermore, it has been suggested that the host’s immune factors may contribute to the development of FG. A study conducted by Mansilla et al.43, demonstrated when matching patients with FG by age and sex, no differences were observed in the OLGA staging. However, patients with FG had a higher bacterial load in the gastric mucosa. The role of H. pylori infection and the development of FG is well-established 1,16,18,44. It has been proposed that chronic inflammation related to chronic superficial gastritis associated with H. pylori infection leads to FG 44,45.

Another part discusses the foundation histopathological observation that supports the central role of H. pylori infection in the pathogenesis of MALT lymphoma. In this sense, it has been postulated that it is the induction of gastric lymphoid follicles, representing the first stage in cancer progression in expanding lymphoid hyperplasia 44,46. Additionally, in a systematic review conducted by Asenjo et al.47, they reported an overall prevalence of H. pylori infection among patients with gastric MALT lymphoma of 75% and a contrast of 60% among patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Although the prevalence of H. pylori infection among MALT lymphoma patients depends mainly on the diagnostic methods used, histological grade, and tumor invasion 47. These studies suggest that H. pylori infection is essential in the pathogenesis of early lymphoma. Furthermore, before the progression to MALT lymphoma, B cell clonality can be identified in chronic gastritis before the development of overt lymphoma 39. However, not current evidence that supporting FG and MALT lymphoma.

Etiopathogenesis

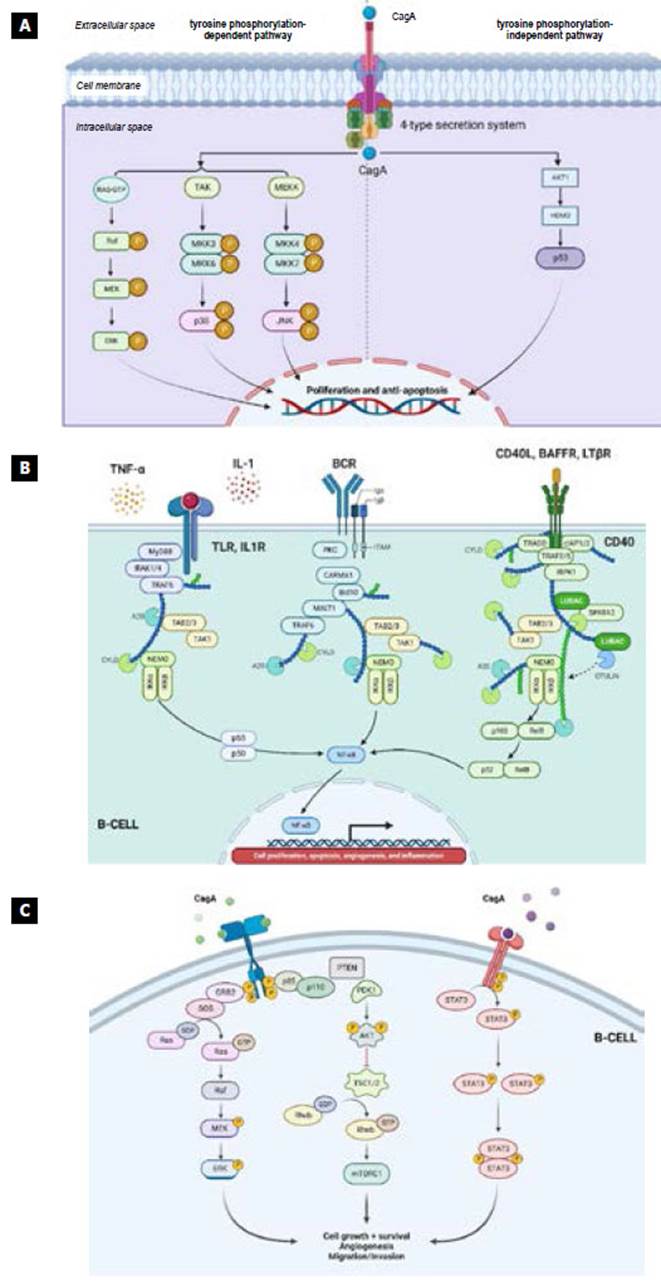

H. pylori infection is the most common chronic infection worldwide and the leading cause of gastroduodenal disease, including chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer, gastric carcinoma, and MALT lymphoma 2,7,8,48-51. Furthermore, a possible association between chronic autoimmune atrophic gastritis and FG has been proposed. This is due to the infiltration and destruction of the gastric mucosa by cross-reactive cytotoxic-specific T cells targeting epitopes of H. pylori bacteria 49. Although the bacteria can colonize all stomach regions, the highest bacterial density has been seen in the antrum and cardia 52, probably because in these anatomical locations, the production of hydrochloric acid is decreased 52-54. Understanding bacterial density is essential as it has been associated with the severity of chronic stomach inflammation 55,56. However, in the study conducted by Mansilla et al.43 demonstrated increased bacterial load without a concomitant rise in mucosal inflammatory cytokine responses in H. pylori infection with FG. These findings suggest that the immune response is variable or an additional mechanism of H. pylori’s active immune evasion response. Thus, further research is necessary in this context. Aside is considered to be part of the immune response to H. pylori infection, which is mediated by the virulence factor cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) 45. Thus, CagA is linked to significant mucosal inflammation, severe atrophic gastritis, and the development of GC 50,57,58 (see Figure 1). It has been proposed that CagA is essential in epithelial tumorigenesis since it is phosphorylated by intracellular proteins, particularly by the protein tyrosine phosphatase-2 (SHP2) that contains the Src-2 and Abl homologous domain, and induces phenotypic plasticity and oncogenesis through the phosphorylation of SHP2, MDM2, p53, NF-κB, ERK and the constitutive activation of the canonical phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase/AKT/mTOR pathway, considered essential in cell apoptosis and proliferation 50,59,60. Likewise, CagA is a highly immunogenic protein that stimulates the production of interleukin-8 (IL-8) and leads to the infiltration of neutrophils in the inflammatory area, the production of free radicals, and DNA damage 59,61,62, increasing the risk of gastric lymphomagenesis 63. Indeed, in vitro experiments have shown that the immune response in extranodal marginal zone B cell lymphoma is mainly produced by T cell-mediated immunity 64. Studies have shown that CagA antigen can translocate to B cell after destruction of the gastric mucosa during chronic gastritis 65,66. In B cells, this antigen prevents apoptosis through extracellular signal-regulated kinase, leading to the proliferation and immortalization of B cells 65-67. CagA antigen can induce proinflammatory responses, such as neutrophil infiltration, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and polyclonal B cell activation in the gastric lumen, causing gastric damage and genetic instability 59,68,69.

Source: The authors.

Figure 1 Signaling pathways associated with FG. A) The direct action of CagA on the tyrosine-kinase dependent and independent pathways. It is observed how, through the type-4 secretion system, the bacteria introduce CagA to the cell cytoplasm, which can activate tyrosine kinase phosphorylation-dependent pathways such as RAF, TAK, MEKK, and the phosphorylation-independent pathways such as AKT1 that regulates HDM2, responsible for modulating p53 called "the guardian of the genome," which has an impact on proliferation and anti-apoptosis. B) The canonical NF-κB pathway is activated by cytotoxin associated with gene A (CagA) through IL-8 and its receptor, which regulate it downstream, whereas the non-canonical pathway is activated more strictly by a set of molecules known as "the members of the TNF superfamily" such as B-cell activating factor (BAFF), lymphotoxin-β and CD40 ligand (CD40L), who may possibly be responsible for the more significant activity of the non-canonical NF-κB pathway due to its role in the interaction between T cells and B cells 16. C) The canonical phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT/mTOR (PI3K/ AKT/mTOR) pathway is activated by the direct action of the virulence factor (CagA) of H. pylori, as well as by the cytokines and chemokines of the persistent chronic inflammatory response. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is essential in cell proliferation and apoptosis.

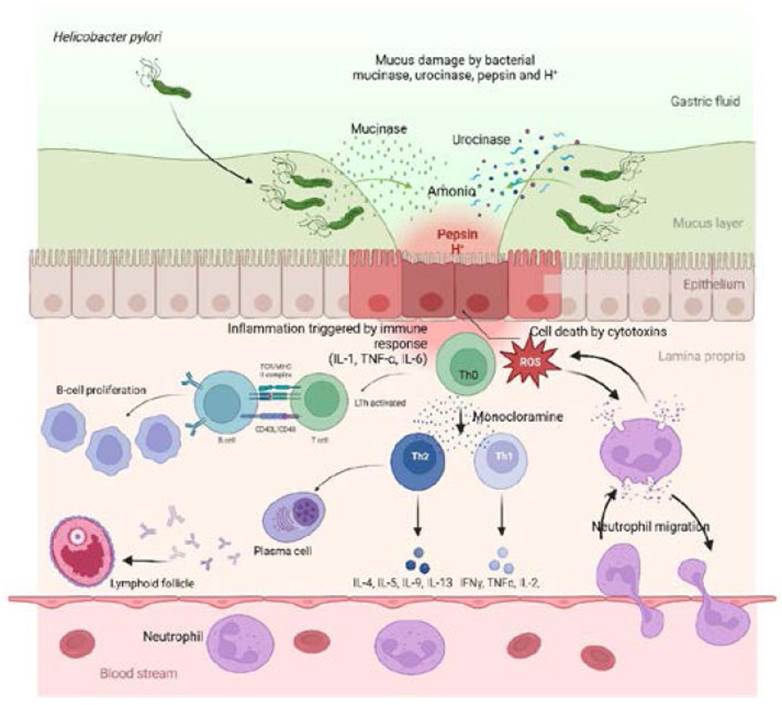

On the other hand, the bacteria’s spiral shape allows it to be mobilized through the viscous gastric mucus using flagella and to avoid peristaltic sweep by attaching to the mucin through a hook-shaped protein, adhesins (BabA, SabA, OipA), and Sialyl-Lewis X antigens 70. The bacteria to evade the acidic microenvironment, through the enzyme urease, establish an environment formed by a cloud of ammonium plus carbon dioxide, increasing the pH 2,50,70,71, which temporarily improves the hostile acidophilic microenvironment 52,72. Monochloramine is an intermediate metabolite result of the combination of ammonium release of the bacterium with chloro ion of the polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells, whose harmful effects include mitochondrial damage, increased gastrin secretion, inhibition of epidermal growth factor, stasis, and alterations in microcirculation 73-77. The cytotoxic effect of monochloramine produces the release of cytokines, which are responsible for differentiating Th0 lymphocytes into Th1 and Th2 lymphocytes. Th1 lymphocytes produce IL-2 and gamma interferon (IFN-γ), promoting cellular immunity, while Th2 lymphocytes produce IL-4 and IL5, which are involved in the activation of B cells, which allows differentiation into plasma cells and production of immunoglobulins; especially, IgG and IgM antibody 78. It has been shown that MALT lymphomas are infiltrated by Th2-polarized T lymphocytes, which favor tumor proliferation and are intensified by intratumoral CD4+ T cells 79. Many of these CD4+ T cells are suppressors of CD25+ lymphocytes, FOXP3+ T cells, and regulatory T cells (Treg) recruited by tumor B cells. A high level of FOXP3+ expression in cells confers a better response to therapy for H. pylori eradication 52,79-81. It has been shown that the immune response of patients is variable, and intricate Th1 and Th2 polarization profiles are found, which explains the heterogeneous histopathological findings in patients with H. pylori infection 52,82. The result of these processes benefits the recruitment of multiple cell types, such as inflammatory cells, T cells, B cells, and plasmacytes, the formation of germinal centers, and the production of antibodies and numerous expression factors and cytokines. This evokes the extraordinary orchestration of the immune system in processes that include tumor growth, survival, progression, invasion, and metastasis 52,79-82 (see Figure 2).

Source: The authors.

Figure 2 The mechanisms of chronic inflammatory response by which H. pylori induces FG. It is observed how the bacteria, through mucinase, urokinase, pepsin, and H+, generate a decrease in the protective layer of mucus and how urokinase forms an ammonium cloud to improve the hostile environment of the bacteria. This, in turn, produces injury and cell death of the gastric epithelium, triggering chronic inflammation and a perpetual immune response with the migration of neutrophils that release proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1, TNF-α, IL-6) that activate LT. In turn, they express CD40L and TCR on their surface to interact with MHC and CD40 receptors, causing sustained and uncontrolled proliferation of BL. On the other hand, Th0, through monochloramine, is polarized into Th1, which releases molecules (IL-2, IFN-γ, TNF-α) and Th2 (IL-4, IL-5). Polarization to a Th2-type immune response allows the activation of LB and differentiates into plasma cells that produce immunoglobulins, leading to the formation of essential lymphoid follicles in FG.

Unlike Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from other species, LPS of H. pylori is recognized by Toll-like receptors (TLR) such as TLR-2 instead of TLR-4 71. Normal lymphocyte function depends on regulating the transcriptional activity of nuclear factor kappa β (NF-κβ). The bacteria interacts with epithelial cells through TLR, which activates the NF-κβ pathway, altering the regulation of signaling pathways and contributing to lymphomagenesis 83,84, inducing release of interleukin-8 (IL-8) and stimulating the expression of intercellular adhesion molecules ICAM-1 85. The NF-κβ pathway is a primary transcription factor usually sequestered in the cytoplasm. It is a point of convergence of several signaling pathways activated at cell surface receptors, including the BCR, which leads to transformations in the expression of genes that modify the immune response, cell survival, proliferation, and apoptosis 84,86. On the other hand, gastric epithelial cells express high levels of HLA-DR during chronic H. pylori infection, with the recruitment of T cells that express CD40 ligand (CD40L) molecules. B cells are stimulated by the CD40L-CD40 interaction associated with the action of various cytokines and chemokines 87,88. Furthermore, elevated expression of the APRIL ligand, a cytokine that is essential for sustained B cell proliferation, has been observed 89, which is produced by macrophages through the induction of H. pylori and H. pylori-specific T cells 90. Likewise, APRIL is produced by eosinophils, B cells located near lymphoid infiltrates, and tumor cells, which suggests the protumorigenic potential of APRIL 91.

On the other hand, Gastrokinase gene (GKN1), which is a tumor suppressor gene that inhibits inflammation 92, it has been proven that its transcript and protein are decreased in the mucosa of patients with FG with H. pylori infection 93,94. As mentioned above, the hormonal factor may participate in the evolution of the disease, which acts exclusively on a Th2-type response; therefore, a significant reduction in inflammatory activity during pregnancy has been demonstrated 95. This phenomenon would explain, to some extent, the greater prevalence of FG in the female population.

The H. pylori bacteria constitute the main inducing factor of an immune response that stimulates the proliferation of lymphoid tissue in the lamina propria, especially MALT, whose function is to protect the surface of the gastrointestinal tract and other exposed mucosa to the external environment. It is currently under discussion whether the activation of B cells with monoclonal proliferation results from an autoimmune response or is an intermediary of persistent stimulation by H. pylori antigens. In this order of ideas, it has been shown that MALT lymphoma B cells express polyreactive surface immunoglobulins (BCR) such as IgG and direct stimulation by alloantigens and autoantigens recognized by surface antibodies that lead to the proliferation of tumor cells. After this oligoclonal expansion, a dominant clonal proliferation can be exposed to the surface through selective pressure 16,44,87. This postulate suggests a possible explanation for the high regression rates in patients with FG and even cases of MALT lymphoma when treatment is instituted to eradicate H. pylori infection. Besides, the development of monoclonal MIB-1 antibodies, a reactive epitope of the nuclear antigen ki67 involved in the proliferation of epithelial cells, has been considered an indicator of cell proliferation in biopsy 96.

A hypothesis has emerged regarding the relationship between bacterial genotypes and certain diseases. The genotypes CagA+ and vacAs1m1 are the most virulent strains associated with peptic ulcers, GC, and severe inflammation 97, while the s2m2 strain generates limited inflammation. In this order of ideas, CagA has been frequently detected in MALT lymphomas, and the response to H. pylori eradication is faster in patients who express CagA 98. However, in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, they were able to determine that there is no significant association between CagA and the development of MALT lymphoma (extranodal marginal zone B cell lymphoma) (OR: 1.30; 95% CI: 0.906-1.866) and an inverse association between VacA and the risk of gastric MALT lymphoma (OR: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.57-1.50) 59; Interestingly, CagA translocated into B cells plays a crucial role in the development of DLBCL, and a significant association was observed with this type of lymphoma (OR: 6.43; 95% CI: 2.45-16-84) 59. The role of bacterial genotypes in the pathogenesis of FG remains unclear. This study demonstrated an association between FG and H. pylori infection (OR: 13.41, 95% CI: 1.7-103, p=0.01). and the iceA1 genotype was more frequent in FG 99.

On the other hand, it is possible that the epigenetic mechanisms may contribute to transforming FG into malignancy 100. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are non-coding RNAs that can bind to messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules, induce RNA degradation, and lead to post-transcriptional gene silencing 101. miR-150 can modulate the c-Myb transcription factor and influence B cell differentiation 102, and its capacity as a tumor suppressor in DLBCL 103. miR-203 has also been linked to the transformation of gastritis to MALT lymphoma due to promoter methylation that leads to the deregulation of ABL1 104. ABL1 serves as a receptor in B cells, signaling through direct interaction with the BCR and the co-receptor CD19 105. Overexpression of ABL1 has been associated with hematopoietic malignancies such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia 106. ABL1 overexpression has been linked to constitutively active BCR signaling and NFκB activation 106; that is, this signaling pathway contributes crucially to the genesis of MALT 64.

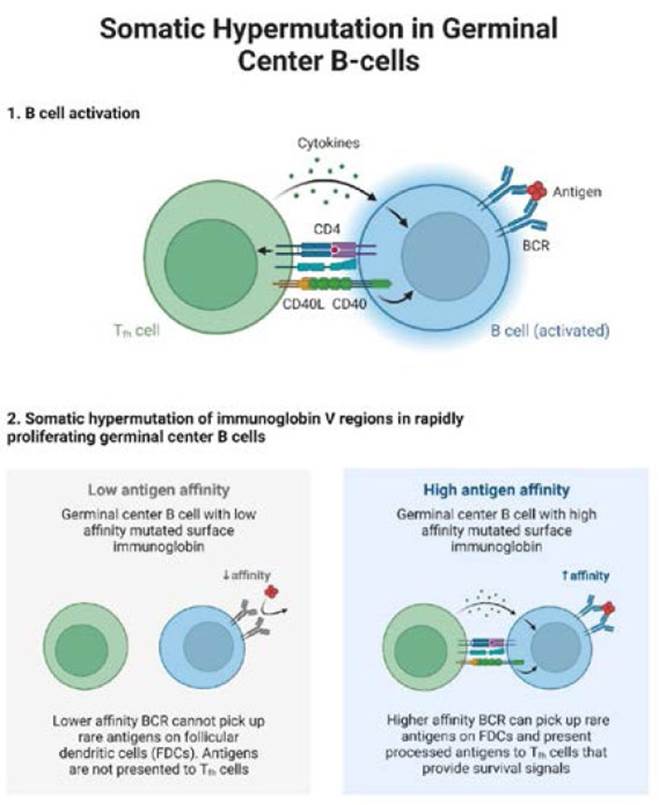

For another part, the role played by the activation of cytidine deaminase (AID) has been raised, some studies have clarified its role in developing low-grade MALT lymphomas because AID is necessary for developing germinal centers 107,108. AID is recognized as the enzyme responsible for regulating the immunoglobulin gene to initiate class switch recombination (CSR), resulting in immunological diversity and chromosomal translocation of the c-MYC transcription factor 109,110. Unfortunately, AID’s function as a genome mutator may target the generation of somatic mutations in several host genes from non-lymphoid and lymphoid tissues, contributing to tumorigenesis 110-112. In particular, aberrant AID expression can be triggered by several pathogenic factors, including H. pylori infection and stimulation of proinflammatory cytokines, while AID expression is absent under physiological conditions 111,112. Therefore, aberrant AID activity in epithelial tissues may provide the critical link between inflammation, somatic mutations, and cancer development 111-113 (see Figure 3). H. pylori infection increases AID expression through the NF-κB pathway in gastric cells, and with the accumulation of the p53 mutation 111. Likewise, AID activity contributes to lymphomagenesis through the aberrant somatic hypermutation of five other circumscribed proto-oncogenes, such as PIM1, PAX5, RhoH/TTF, and c-MYC114-118

Source: The authors.

Figure 3 Somatic hypermutation and class recombination for its activation by activated cytidine deaminase (AID) in lymphoid proliferation. In the first phase, the activation of B cells through the interaction of CD40-CD40L and MHC-TCR allows the release of cytokines. The B cell, when active, recognizes the antigens of the foreign agent through the BCR. In the second phase, somatic hypermutation of the V regions of the immunoglobulin in the proliferation of the germinal centers of B cells, which the germinal centers are divided by a low and high antigen affinity of the immunoglobulin of the mutated surface for the antigen, which leads to the BCR can pick up rare antigens on follicular dendritic cells (FDC) and present processed antigens to Th cells, that provides survival signals.

Additionally, some genetic abnormalities associated with MALT lymphomas have been identified, the most common being the t(11;18), (q21;q21) translocation, which generates a chimeric protein product of the API-MALT2 fusion that can increased inhibition of apoptosis conferring more remarkable survival to MALT lymphomas. This translocation should be considered after treatment failure or remission following H. pylori eradication 119. Other alterations have been described such as the translocation (p22;q32), t(14;18), (q32;q21), t(3;14), (p14.1;q32) 87. Similarly, there is a high prevalence of HLA-DQA1*0103, HLADQB1*0601 and the R702W mutation in the NOD2/CARD15 gene 120,121. Additionally, the presence of TNF-857T has been linked 122, and one TLR type 4 allele (TLR4 Asp299Gly) 87.

Similarly, at the pathological level, mutations of the p53 protein and the BCL-10 gene are described, which are acquired by the capacity for constitutive activation of NF-κB signal pathway independent of antigenic stimulation when they are overexpressed through the control of promoter regions or hyperactive enhancers from chromosomal translocations 52,70,81,123-128. The BCL-10 gene, located on chromosome 1, is regulated by the IgH immunoglobulin gene on chromosome 14 and results in anarchic expression of the BCL-10 gene 129. In that order, the expression of the BCL-10 protein, which is found at the intracellular level, is essential for the development, differentiation, and function of mature B and T cells 87. Likewise, BCL-10 (B-cell lymphoma 10) protein may be involved in resistance to antimicrobial therapy. A study conducted by Yepes et al.124. In a study of a Colombian population, the significance of t(11;18)(q21;q21), BCL-10 expression, and H. pylori infection in MALT lymphoma was evaluated. The study found that MALT lymphoma cases positive for the translocation and those with nuclear BCL-10 overexpression showed a 66% eradication rate of H. pylori.

Diagnostics

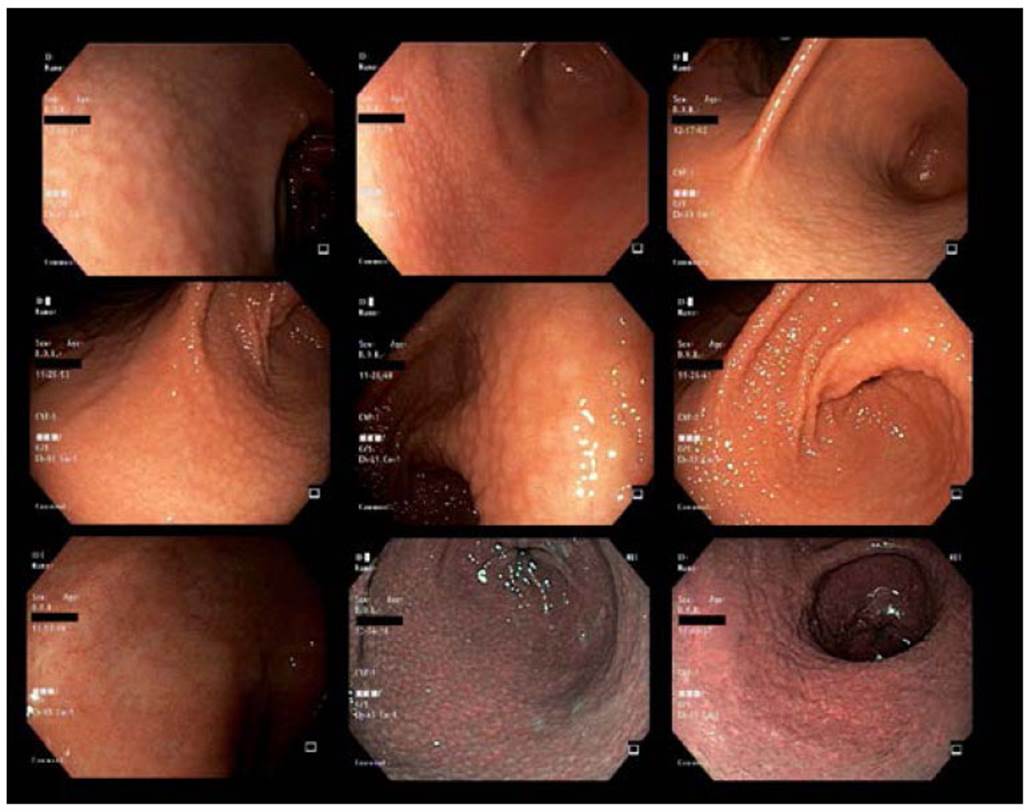

FG diagnosis can be made through endoscopic study and histopathological analysis, considered the standard diagnostic methods to confirm the pathology 23,130. During upper endoscopy, gastric mucosa with multiple nodular formations of a uniform spectrum, predominantly in the antral location, is observed. However, it can extend to other regions of the gastric body, such as small elevations with superficial erosions and, eventually, ulcerations 23,131,132 (see Figure 4). These findings have been documented in both adults and the pediatric population 133,134. Although FG is a designation that is not found in the Sydney classification system for gastritis 23,135, In the Kyoto classification, if the term "nodularity" has been added, which is described with the findings in H. pylori infection 6,131,136,137. It must also be considered that FG and MALT lymphoma may overlap and cause difficult endoscopic diagnosis, mainly when FG is present in the body 31,131,138. Similarly, the histopathological obstacle in differentiating FG and MALT lymphoma has been described 139-142. According to this, Hummel et al.141, they investigated B cell clonality in cases of chronic gastritis (Wotherspoon scores 1 and 2, N=53), gastric MALT lymphoma (Wotherspoon score 5, N=26), and ambiguous histology (Wotherspoon scores 3 and 4, N= 18). The authors noted that B cell clonality was found in 1/53 cases of chronic gastritis (1.9%), 24/26 cases of lymphoma (92.3%), and 4/18 cases with ambiguous histology (22.2%). These similarities and overlaps in pathological, cellular, and molecular features between FG and MALT lymphoma entities are interesting for further research 131,141.

Source: Provided by the authors Arnoldo Riquelme and Gonzalo Latorre at Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile.

Figure 4 Endoscopic findings of FG.

The confirmative diagnosis of the disease depends on the histopathological study of the gastric mucosa in which a mixed inflammatory aggregate and lymphoid follicles with a germinal center are recognized. It is expected to find PMN cells such as neutrophils, ulceration, erosion, and extensive fibrosis 143,144. The histological findings of a low-grade MALT lymphoma are expressed with cell proliferation in the presence of the centrocyte, cellular infiltration of plasma, and lymphoepithelial lesions defined as an invasion and partial destruction of the gastric glands and crypts, which are the main characteristics of lymphoma 145,146. However, differentiating between low-grade MALT lymphoma and FG sometimes represents a real diagnostic challenge. Furthermore, immunohistochemistry, cytogenetics, and molecular biology studies are helpful in these cases 147. Furthermore, the analysis of aberrant genes for heavy chain immunoglobulins and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is widely used as a complementary method 141.

It is worth mentioning that lymphomas exhibit microsatellite instability, allelic imbalance, and trisomy, mainly from chromosome 3, which has been related to the expression of BCL6, FOXP1, and CCR4 in the development 87,114,148,149. Likewise, this abnormality can be determined by immunofluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in paraffin blocks 150. Approximately 50% of MALT lymphoma have the chimeric fusion protein API2-MALT1, a product of the t(11:18) translocation that allows constitutive activation of the NF-κB signal pathway; however, this alteration is absent in FG 83,151.

Immunohistochemical studies allow determining the nature of the lymphoid infiltrate and the origin of the MALT lymphoma. However, it is not possible at some point with the tests to distinguish with certainty between a malignant process and a reactive condition. Besides, the combination of the panel of B antigens such as CD3, CD19, CD20, CD79a, and anti-pan cytokeratins has been recommended, in addition to the absence of CD5, CD10, CD23, and the expression of cyclin D1, they are helpful in the detection of infiltration of the mucosal epithelium by B lymphocytes, a condition that defines the lymphoepithelial lesion and establishes the diagnosis of MALT lymphoma 147,152. The use of immunohistochemical markers to determine the cellular monoclonality of neoplasms has a limited contribution, given that this finding is also shared with some lymphoid follicles of FG 125. It has been shown that in this pathology, cells can show variable proliferation, such as polyclonal, monoclonal, and oligoclonal 26. From what was mentioned above, pseudolymphoma, the name of this entity, is derived. For the reasons previously stated, the Committee for the Classification of Tumors of the Digestive System of the WHO establishes the histopathological study as the gold standard for the differentiation between reactive and neoplastic infiltrate, while additional studies may represent valuable tools in some instances 153. The findings that favor the diagnosis of pseudolymphoma in the biopsy are the proliferation of blood vessels, lymphoid follicles with evident germinal centers, and the absence of lymphoepithelial lesions. A grading system for lesions has been created from 0 to 5 to provide greater security in the diagnosis, with grade 0 being normal and stage 5 defining low-grade lymphoma. This system includes parameters such as lymphoid aggregates, secondary lymphoid follicles, immature lymphocytes, and infiltration of the epithelium 140,154.

Treatment

H. pylori eradication is the standard initial treatment for MALT lymphomas in all stages. However, 70-80% of the pathological condition in stage I is remitted longterm 1,155,156. On the other hand, in patients who are negative for H. pylori after routine diagnostics exclude infection, the cure is obtained in 30% of patients, so it should always be considered a first step in management 1,157. However, in MALT lymphomas that transform into DLBCL, in some cases, the same benefit is obtained, mainly when they are dependent on positive H. pylori158. Unlike DLBCL, which lacks histological evidence of MALT lymphoma or negative-H. pylori, it has been proven that they are entities with different biological and molecular behaviors 159, Insofar as DLBCL that do not respond to H. pylori eradication, chemotherapy remains the standard therapeutic option 158. One study found that patients with MALT lymphoma negative for H. pylori had a more advanced clinical stage than patients with positive-H. pylori (p=0.023). The t(11;18)/ API2-MALT1 frequency did not differ between positive-H. pylori cases (45.5%) and negative-H. pylori cases (55.6%) and only 38/51 (74.5%) positive-H. pylori cases achieved complete regression after eradication, while 40% were negative-H. pylori cases achieved regression, which allows us to infer that the evaluation of t(11;18)/API2-MALT1 should be considered after failure of remission due to H. pylori eradication 119.

Although more studies are required in this regard, recent literature indicates that H. pylori eradication is helpful in reversing FG with the usual treatments 154,160. In a clinical trial on 66 patients with FG associated with H. pylori (31 with FG vs 35 with NFG), triple therapy for H. pylori eradication was administered. At two weeks of follow-up, 44 patients completed treatment (21 with FG vs. 23 with NFG), of which the H. pylori eradication in the FG group was 43% and in the NFG group, it was 74% 154. Furthermore, lymphoid follicles in 43% of FG patients disappeared after eradication therapy. The above highlights the importance of corroborating bacterial eradication after treatment 154.

Conclusions

FG is a form of chronic gastritis characterized by a dense mixed inflammatory infiltrate with the formation of secondary lymphoid follicles in the lamina propria. The incidence in Colombia is 8.4%, and its etiopathogenesis is influenced by factors such as age, gender, immune response, and H. pylori infection.

The diagnosis is established by upper digestive endoscopy and careful histopathological analysis of the gastric mucosa. The most common site is the antrum, so taking biopsies by the gastroenterologist must include representative sampling at this level.

The disease’s importance derives from H. pylori’s fundamental role in the FG. On the other hand, the bacterial load is not matched with cytokines levels in the inflammatory response, which suggests an alternative mechanism of immune evasion. Further research is crucial for resolving these enigmatic questions.

Treatment for H. pylori eradication is the backbone of managing FG, and its elimination must be verified for UBT (urea breath test), RUT (rapid urea test), or stool antigen tests according to available resources and geographic differences.

The field of research is broad and requires knowledge of the entity. In this sense, cellular and molecular mechanisms studies of H. pylori and FG are necessary. Furthermore, prospective studies must be carried out to demonstrate the association between FG and progression to MALT lymphoma.