Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO  uBio

uBio

Compartir

Revista Peruana de Biología

versión On-line ISSN 1727-9933

Rev. peru biol. vol.25 no.3 Lima jul./set. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/rpb.v25i3.15228

TRABAJOS ORIGINALES

Vascular flora and phytogeographical links of the Carabaya Mountains, Peru

Flora vascular y conexiones fitogeográficas de las montañas Carabaya, Perú

Paúl Gonzáles1 , Blanca León1,2,3 , Asunción Cano1,2 and Peter M. Jørgensen4

1 Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Museo de Historia Natural, Departamento de Dicotiledóneas. Av. Arenales 1256, Lima-14, Perú.

2 Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Instituto de Investigación de Ciencias Biológicas Antonio Raimondi.

3 Department of Geography and the Environment, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712-0530, USA.

4 Missouri Botanical Garden-St. Louis, MO 63166, USA

Abstract

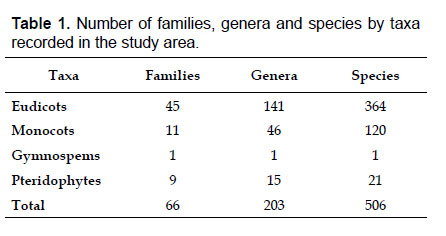

Studies of floristic composition and plant species richness in tropical mountains support their recognition as areas of high biological diversity, and therefore of their importance for plant conservation. Here, we present data on the flora of the high Andes of eight sites centered in the Carabaya mountains, and also provide a floristic comparison with nine other floras within Peru and northern Bolivia. The study area includes 506 species of vascular plants, grouped in 203 genera and 66 families. The highest species richness was found in two families: Asteraceae and Poaceae, which collectively encompass 37% of all species. Other important families were Caryophyllaceae, Fabaceae, Malvaceae, Brassicaceae, Caprifoliaceae, Gentianaceae, Plantaginaceae and Cyperaceae. The most diverse genera wereSenecio, Calamagrostis, Poa and Nototriche. Perennial herbs were the dominant growth form. The vascular flora of the Carabaya Mountains is closely related to those of other regions of southern Peru. Also, more than half of all vascular plants registered for the Carabaya Mountain occur in the Andean region of Bolivia, which shows the undoubted geophysical and phytogeographical connection of the Carabaya and the Bolivian Apolobamba Mountains. This study also shows that there is still a need for more extensive plant collecting and future exploration, since the Carabaya, as other parts of Perus high Andes are subject of dramatic change that may threaten these plant populations.

Keywords: High Andean flora; Peru; floristic composition; taxonomy.

Resumen

Los estudios sobre la composición florística y riqueza de especies en montañas tropicales apoyan su reconocimiento como áreas de alta diversidad biológica, y, por tanto, de su importancia para la conservación. En este trabajo presentamos datos sobre la flora altoandina de ocho sitios localizados en la Cordillera de Carabaya, proveemos también una comparación florística con otros nueve lugares tanto en Perú como en el norte de Bolivia. El área de estudio incluye 506 especies de plantas vasculares, reconocidas en 203 géneros y 66 familias. Las tasas más altas de riqueza de especies se hallan en dos familias: Asteraceae y Poaceae, que colectivamente abarcan el 37% de todas las especies. Otras familias importantes fueron Caryophyllaceae, Fabaceae, Malvaceae, Brassicaceae, Caprifoliaceae, Gentianaceae, Plantaginaceae y Cyperaceae. Los géneros más diversos fueron Senecio, Calamagrostis, Poa y Nototriche. La forma de crecimiento predominante fueron las hierbas perennes. La flora vascular de la Cordillera Carabaya está muy relacionada con otras regiones del sur de Perú. Además, más de la mitad de todas las plantas vasculares registradas para la Cordillera Carabaya se encuentran en la región andina de Bolivia, lo que demuestra la indudable conexión geofísica y fitogeográfica entre las cordilleras Carabaya y Apolobamba de Bolivia. Este estudio también demuestra la necesidad de una extensa colección botánica y futura exploración, desde que Carabaya, como otras partes de los altos Andes del Perú, están sujetos a cambios dramáticos que amenazan las poblaciones de esas plantas.

Palabras clave: flora altoandina; Perú; composición florística; taxonomía.

Introduction

The high Andes are places of concern due to the foreseeable effects of climate change (Markham et al. 1993, Beniston 1994, Thompson et al. 2006, Conde & Saldaña 2007, Pauli et al. 2003, 2007, Young 2014). In Peru, high Andean sites cover close to 16% of the total country area, and they are highly vulnerable to landscape changes that may affect its vegetation and components (Rodriguez & Young 2000, Young 2011). The urgency for the development of conservation strategies for sites and plant species is widely recognized; however, it faces challenges in relation to the dynamism and complexity of environmental changes and their interactions with human influences (Markham et al. 1993, Fort 2015, Kohler et al. 2014).

The Peruvian high Andes (above 3500 m) includes an interesting native vascular flora estimated to consist of more than 2000 plant species (see Jørgensen et al. 2011), of which nearly 32% of them are endemic to Peru. This region has recently seen an increase in taxonomical and ecological studies, accompanied by plant recording and exploration (e.g. Ballard and Iltis 2012, Al-Shehbaz et al. 2013, 2015a, 2015b, Gonzáles et al. 2015, Gonzáles & Cano 2016, Montesinos-Tubée et al. 2015, Linares et al. 2015, Ospina et al. 2016, Sylvester et al. 2016a, 2016b). The completion of the Bolivian catalog (Jørgensen et al. 2014) also provides needed data for a floristic comparison to understand plant richness in the Andes, and floristic connections. Here, we present a compilation of the vascular plant flora of a mountain range in southern Peru: the Carabaya Mountains. We asked how taxonomic richness of our study area compares to other parts of the Andes, particularly to neighboring sites in Peru, and northern Bolivia. The Carabaya is geographically linked to Bolivia through the Apolobamba Mountains, and so we asked if richness and composition at high elevations are similar. We also explore the potential implications of our findings for plant conservation based on the state of knowledge of the high Andean flora.

Material and methods

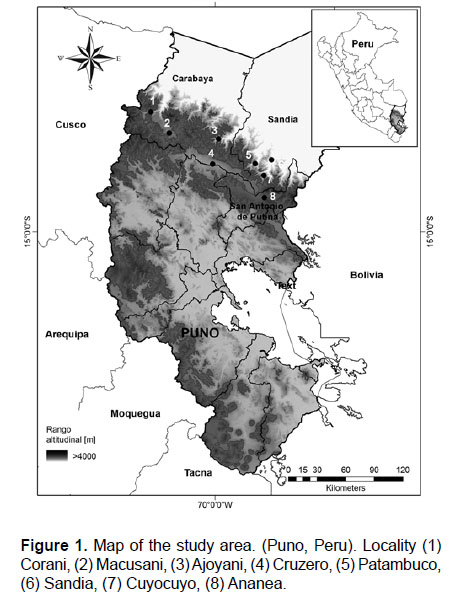

Study area.- The study area encompasses the high Andes between 4000–5300 m of the Carabaya Cordillera, along the eastern Andes in Puno, between 13°50'–15°05' S and 69°58'–70°58' W, crossing the provinces of Carabaya, Sandia and San Antonio de Putina (Fig 1). The Carabaya also includes the largest tropical glacier system: Quelccaya, an area that has contributed to our understanding of climate change (Thompson et al. 2003, 2006, 2013). The Carabaya Mountains extends into Bolivian territory, and in the Department of La Paz, the northeastern Andes are known as the Apolobamba Mountains (Argollo et al. 1987, Argollo & Iriondo 2008). We obtained field data from eight sites (Fig. 1).

In the Carabaya we recognize four vegetation formations: puna grasslands; rock vegetation dominated by chasmophytes; high Andean wetlands; river shores and lakes, and periglacial areas including cryoturbated soils and subnival pumices (Weberbauer 1945, Galán de Mera et al. 2014, Montesinos–Tubée et al. 2015a).

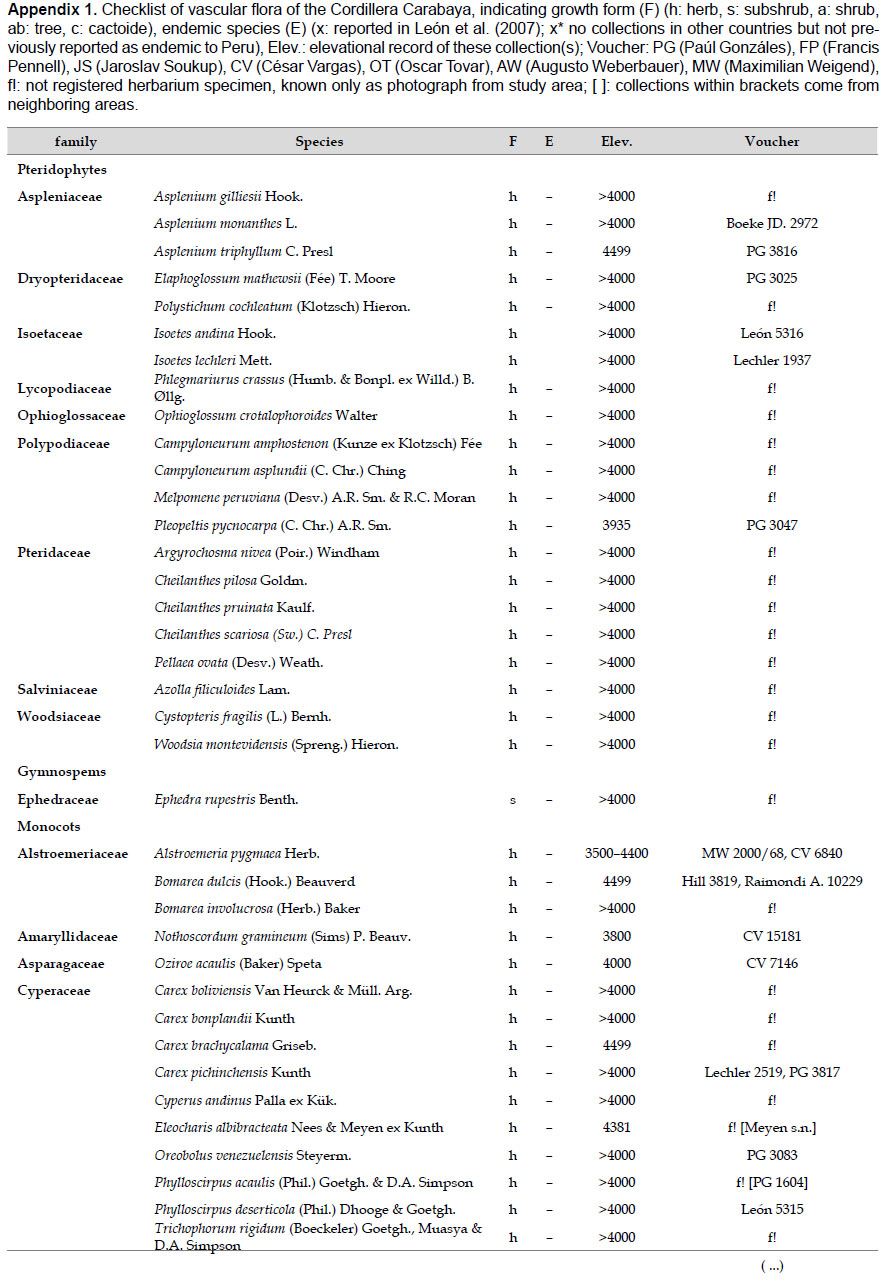

Collection and species identification.- We compiled all species names, habitats, and distribution information initially based on specimens collected by the authors for the study area. For each species from the Carabaya, we gathered information on collectors and collection number. However, for a small group of species that had only been recorded by photo or by authors' field notes, and lack a herbarium voucher, we cited other collections made in neighboring areas. All collections from the study area were identified using taxonomical keys and descriptions available from the botanical literature (Macbride 1936, Tovar 1993, and others). A few reported species were excluded, for example a photo of Stangea rhizantha did not match the species (Linares et al. 2012), and Valeriana globularis (Linares et al. 2012) was replaced by its correct spelling, Valeriana globularioides Graebn.

We also compiled all records for eight floras at high elevations, three sites (Parinacochas, Juli and Tambo Ichuna) were located above 3100 m elevation on the Pacific Basin, and the remaining five sites (from north to south: Cordillera Blanca, Concepcion, Bofedales, Apacheta and Vilcanota) were located above 4000m. Species considered as national endemics were recorded from León et al. (2007), Al-Shehbaz et al. (2013, 2015a, 2015b), Gonzáles et al. (2015), Montesinos-Tubée et al. (2015b), and Gonzáles and Cano (2016).

For the flora of the Department of La Paz in northern Bolivia, we downloaded the species records from the Bolivia Catalog database (http://www.tropicos.org/ProjectAdvSearch.aspx?projectid=13&langid=66).

Specimen data were also obtained from online sources of several institutions (e.g., Field Museum Neotropical specimens [http://fm1.fieldmuseum.org/vrrc/], the Tropicos® database of Missouri Botanical Garden [http://www.tropicos.org/], New York Botanical Garden digital herbarium [http://sciweb.nybg.org/Science2/vii2.asp]), the digital herbarium portion of Atrium [http://atrium.andesamazon.org/digital_herbarium.php], JSTOR [https://plants.jstor.org/). We also included or reviewed collections of the following herbaria B, BM, CUZ, F, G, GH, HUSA, HUT, K, LIL, LP, MO, MOL, NY, S, US and USM (Index Herbariorum). The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group IV (2016) classification system was used for the management of the angiosperm taxa.

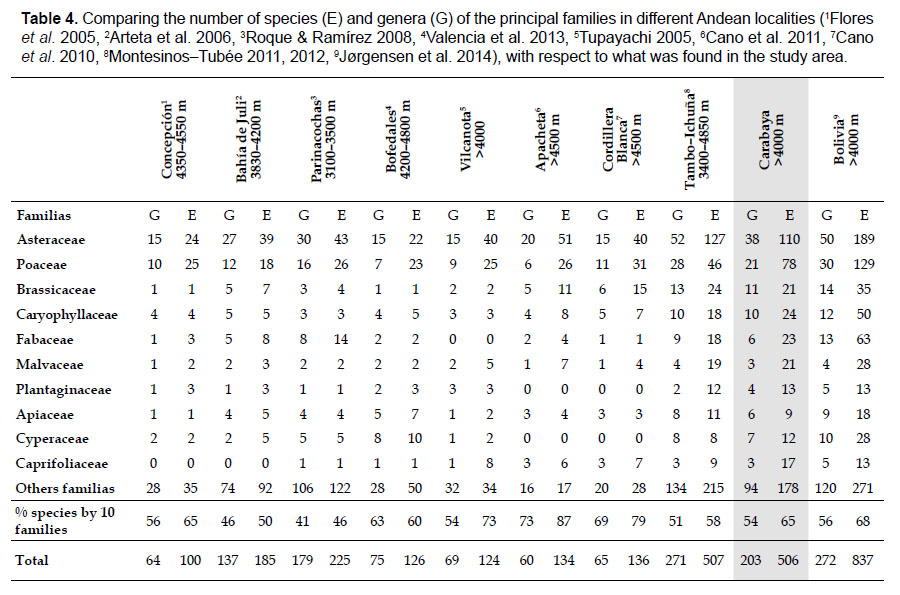

Floristic comparison.- Our database of all taxa was compa-red with checklists of nine studies in the high Andes. These nine sites encompass about seven degrees of latitude (8°50 – 17°26 S), and represent both Pacific and Amazon basins. Within these sites there are a variety of habitats from open grasslands, rocky places, shrublands and wetlands. Four floras represent mostly wetlands and surrounding areas (Flores et al. 2005, Arteta et al. 2006, Roque & Ramírez 2008, Valencia et al. 2013), two floras represent sites located in periglacial areas with processes of cryoturbation (Cano et al. 2010, 2011), and four floras represent large or detailed surveys in the puna ecosystem (Tupayachi 2005, Montesinos-Tubée 2011, 2012, Jørgensen et al. 2014).

Results

We recorded over 10000 plant collections for all nine sites in the Peruvian Andes. This sampling effort still represents a low collection density index with a CDI (specimens/100 km2) of nearly 5. For southern Peru, and particulary for Puno (up to 4000 m), the largest plant collections were made by Augusto Weberbauer, César Vargas, Hugh Weddell, Franz Meyen, Jaroslav Soukup, Francis Pennell, Werner Rauh, Wilibald Lechler, Alfredo Tupayachi, Oscar Tovar and Dora Stafford, all of them made during the 19th and 20th centuries.

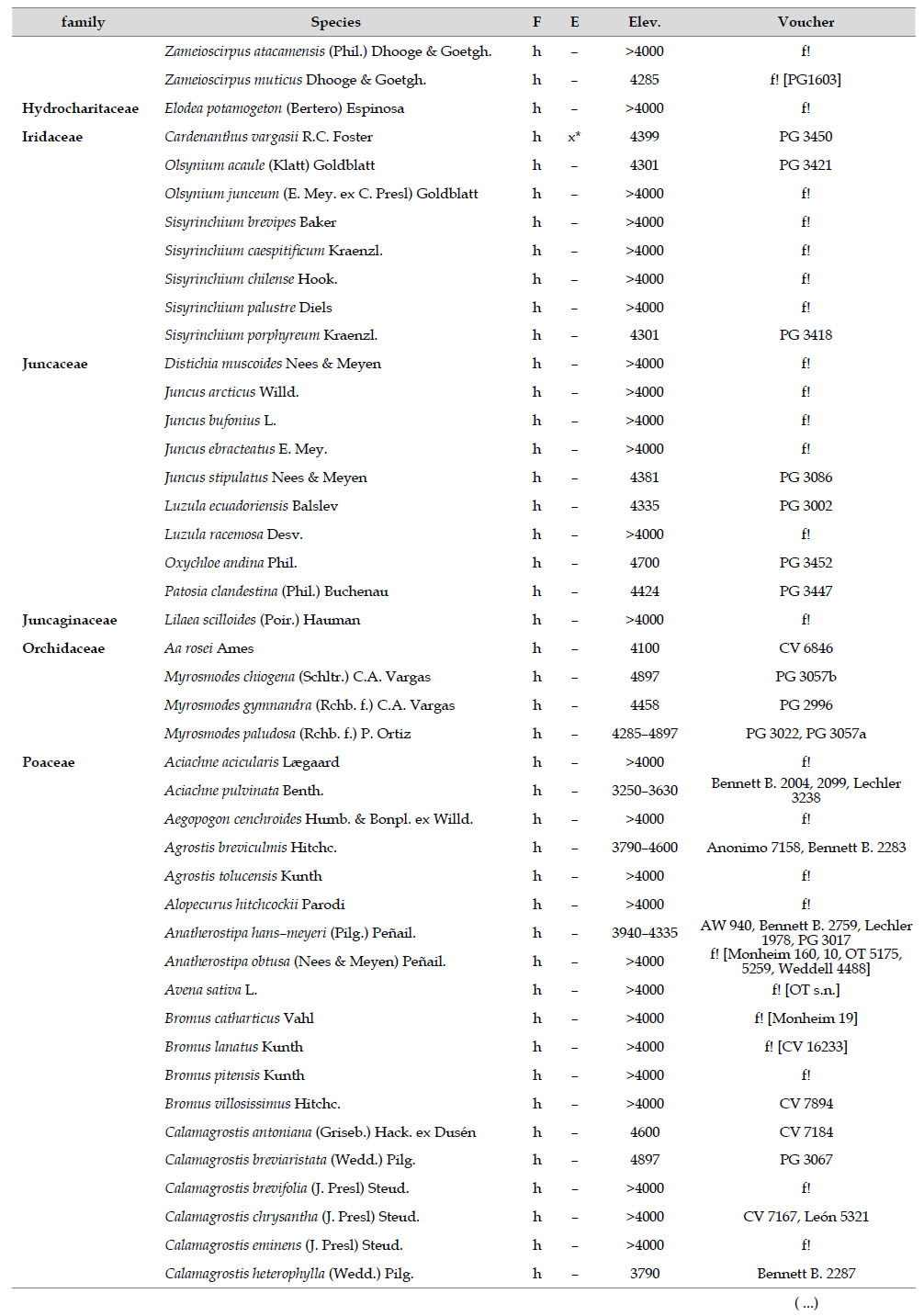

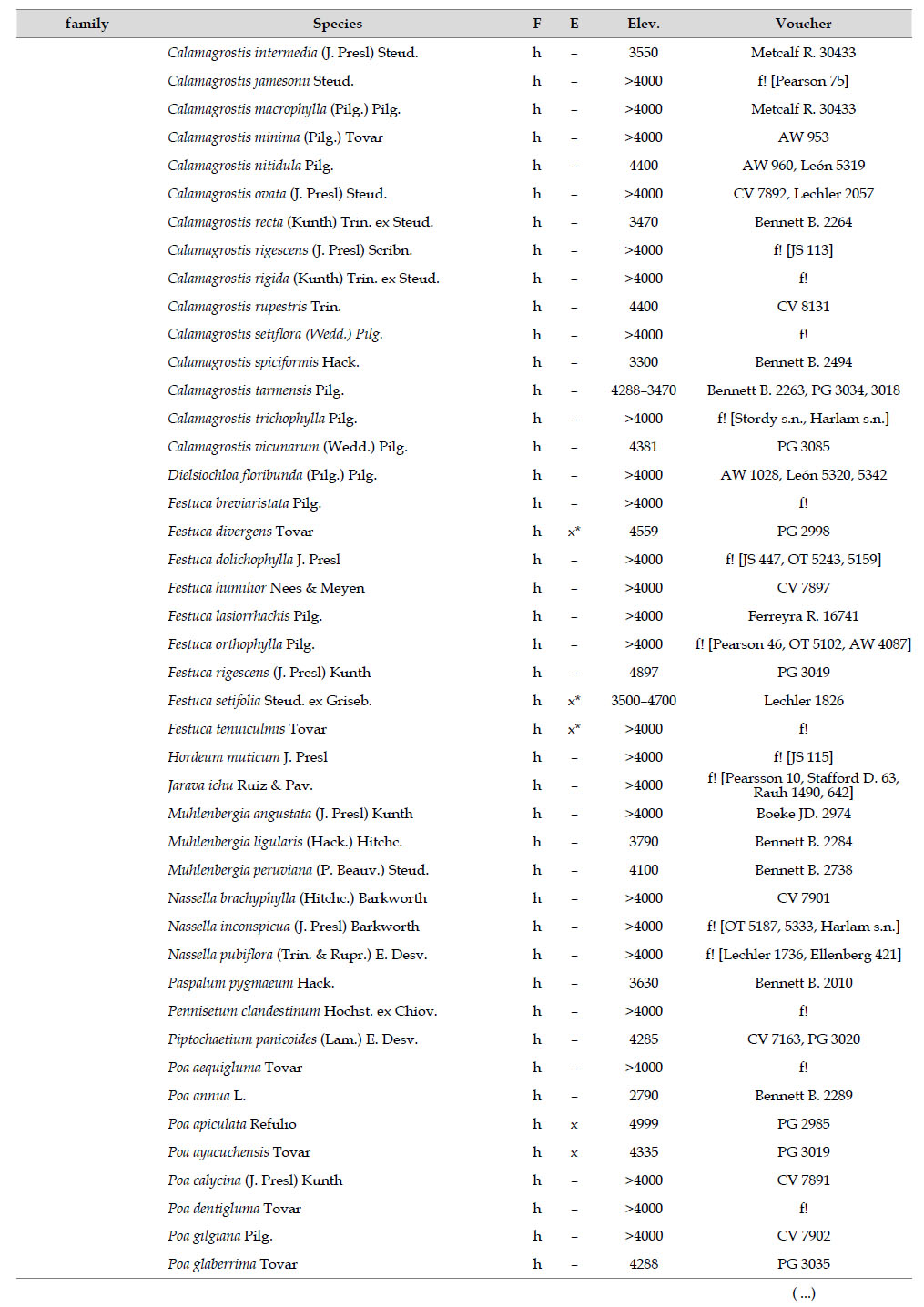

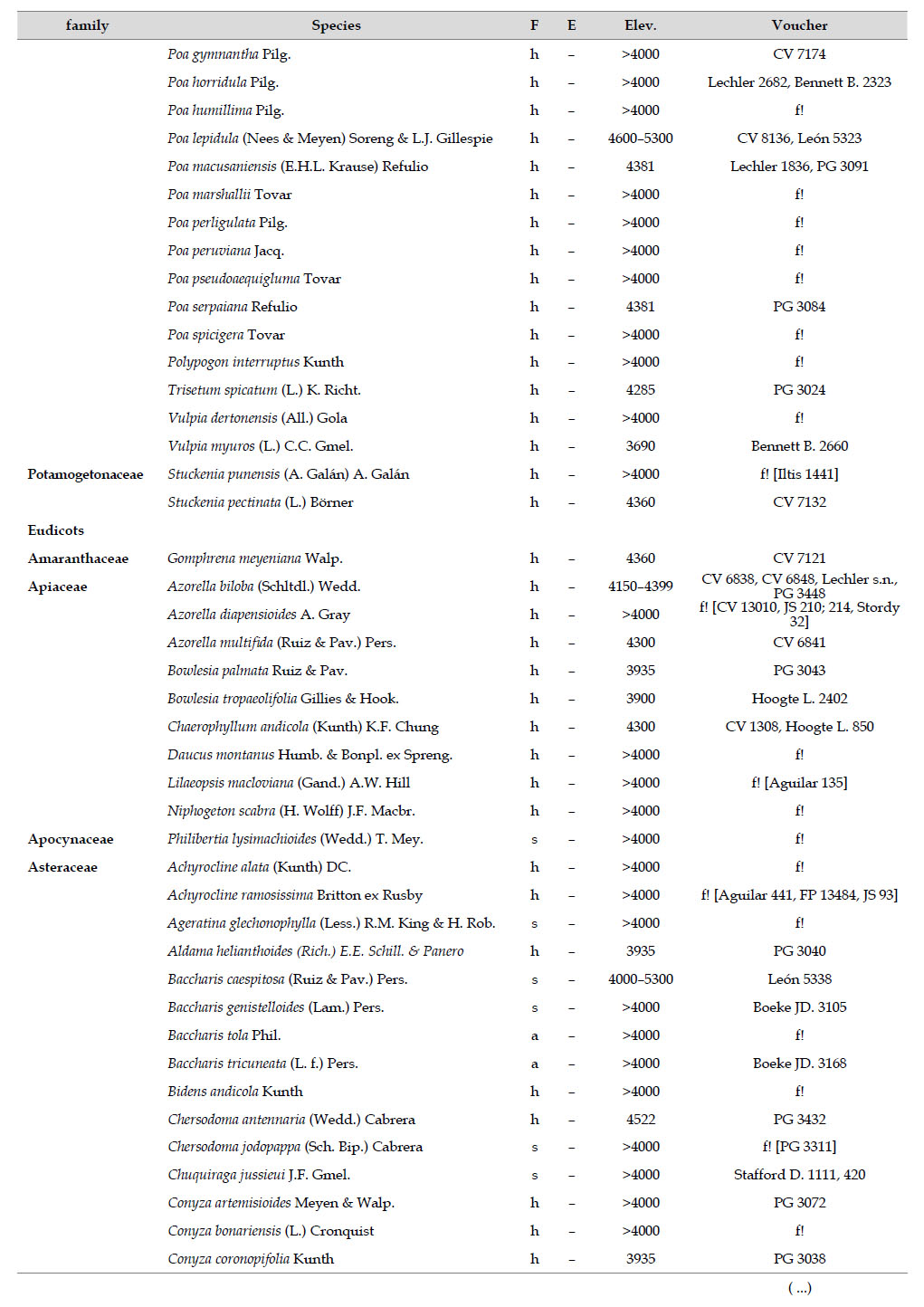

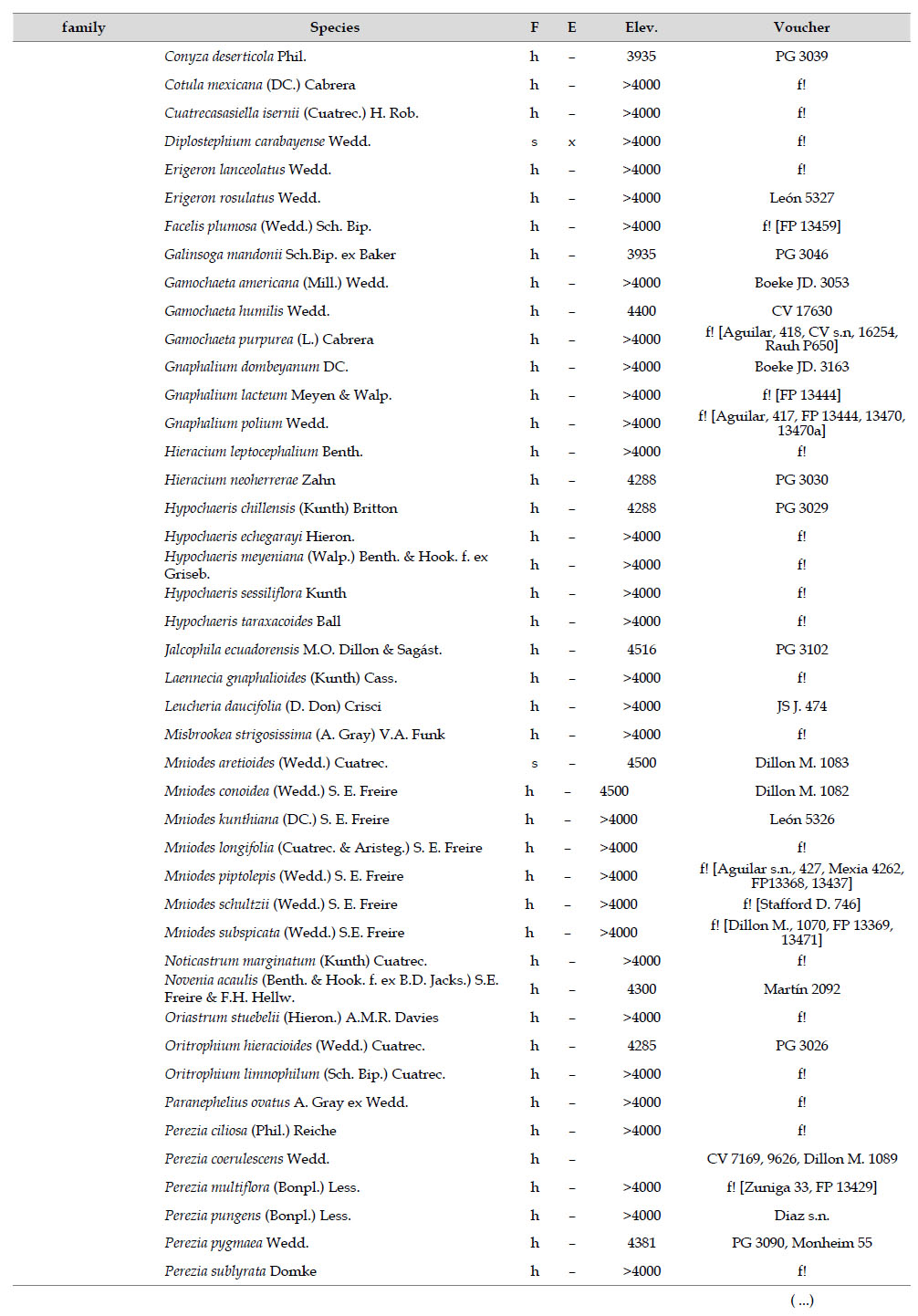

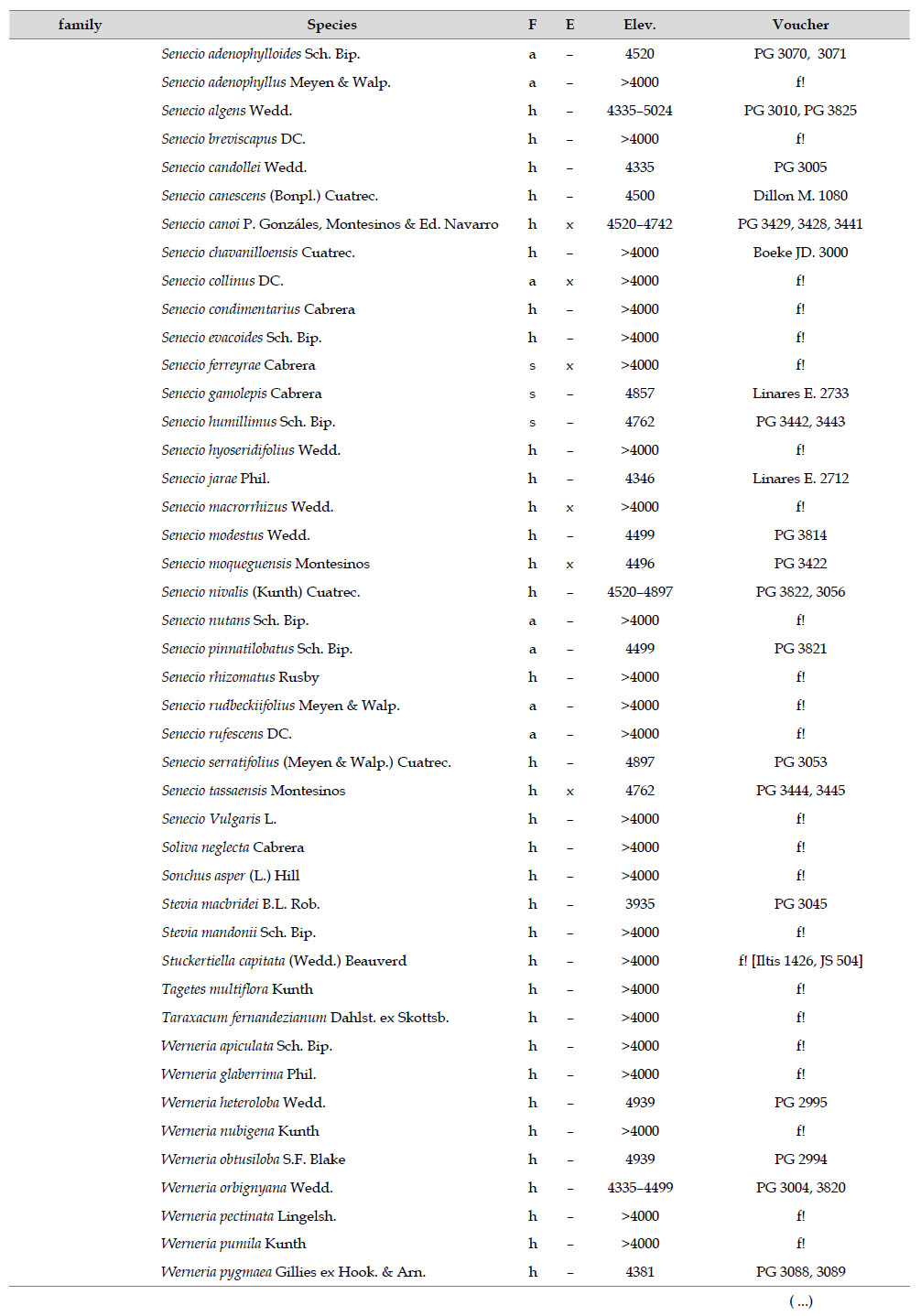

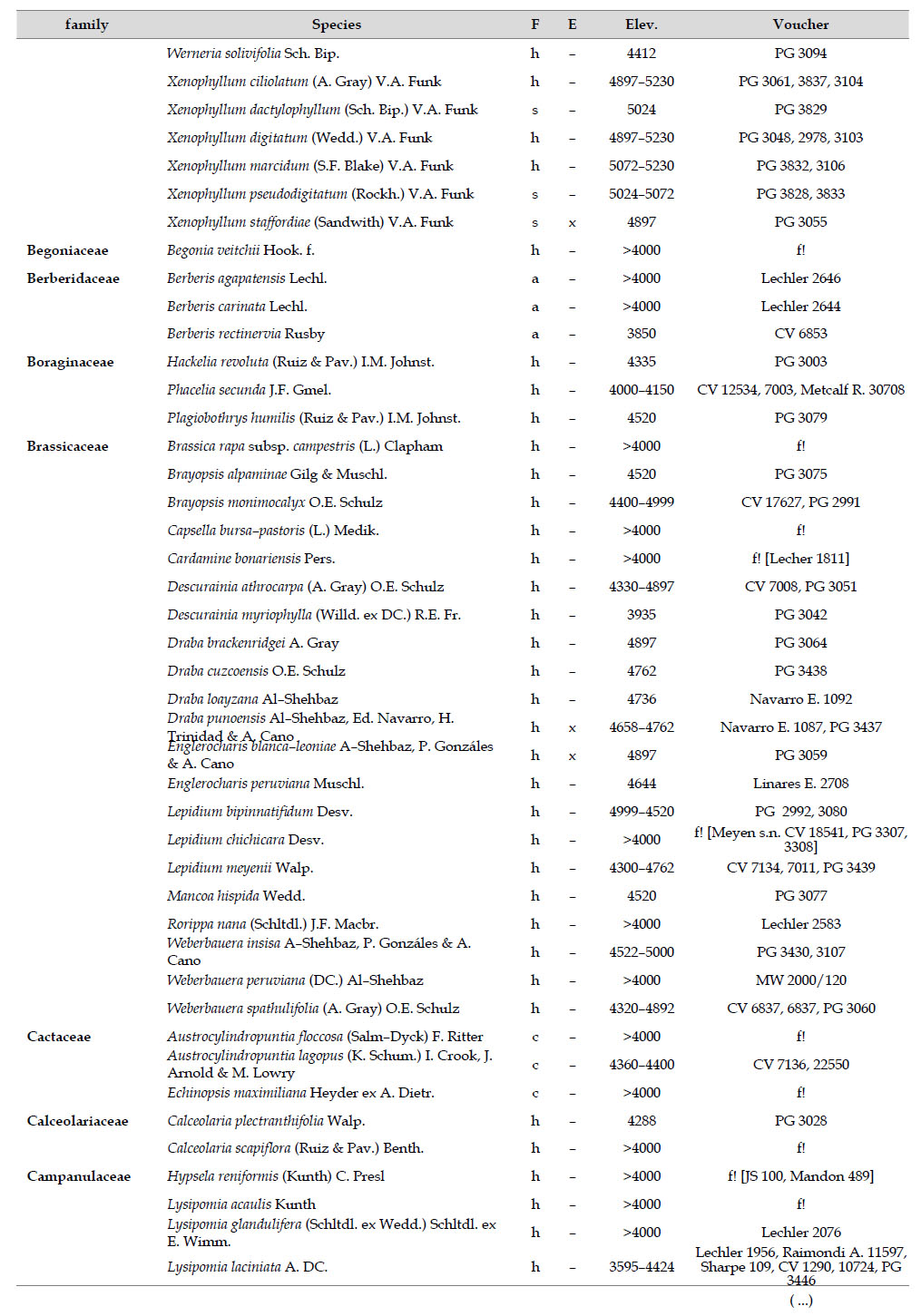

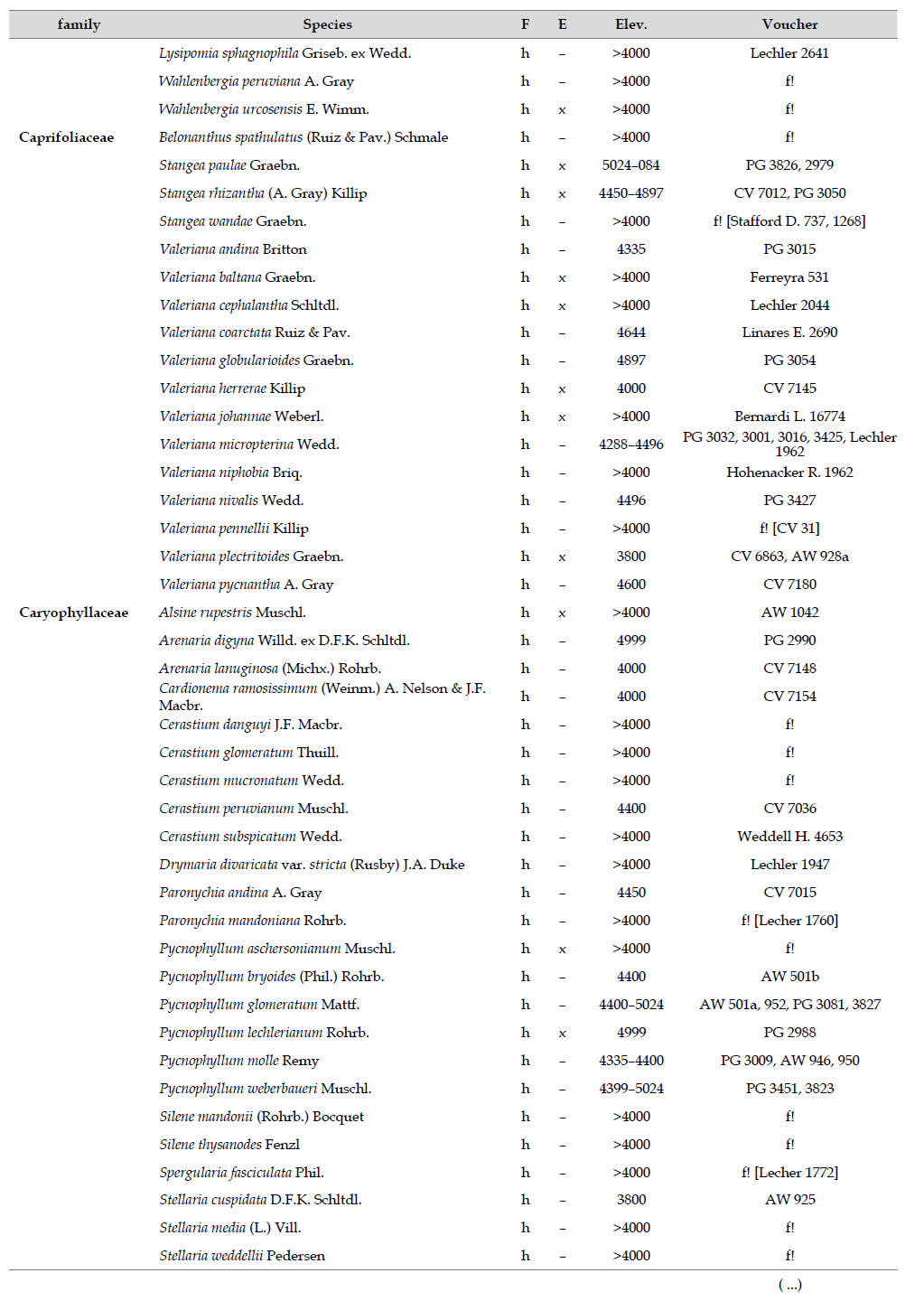

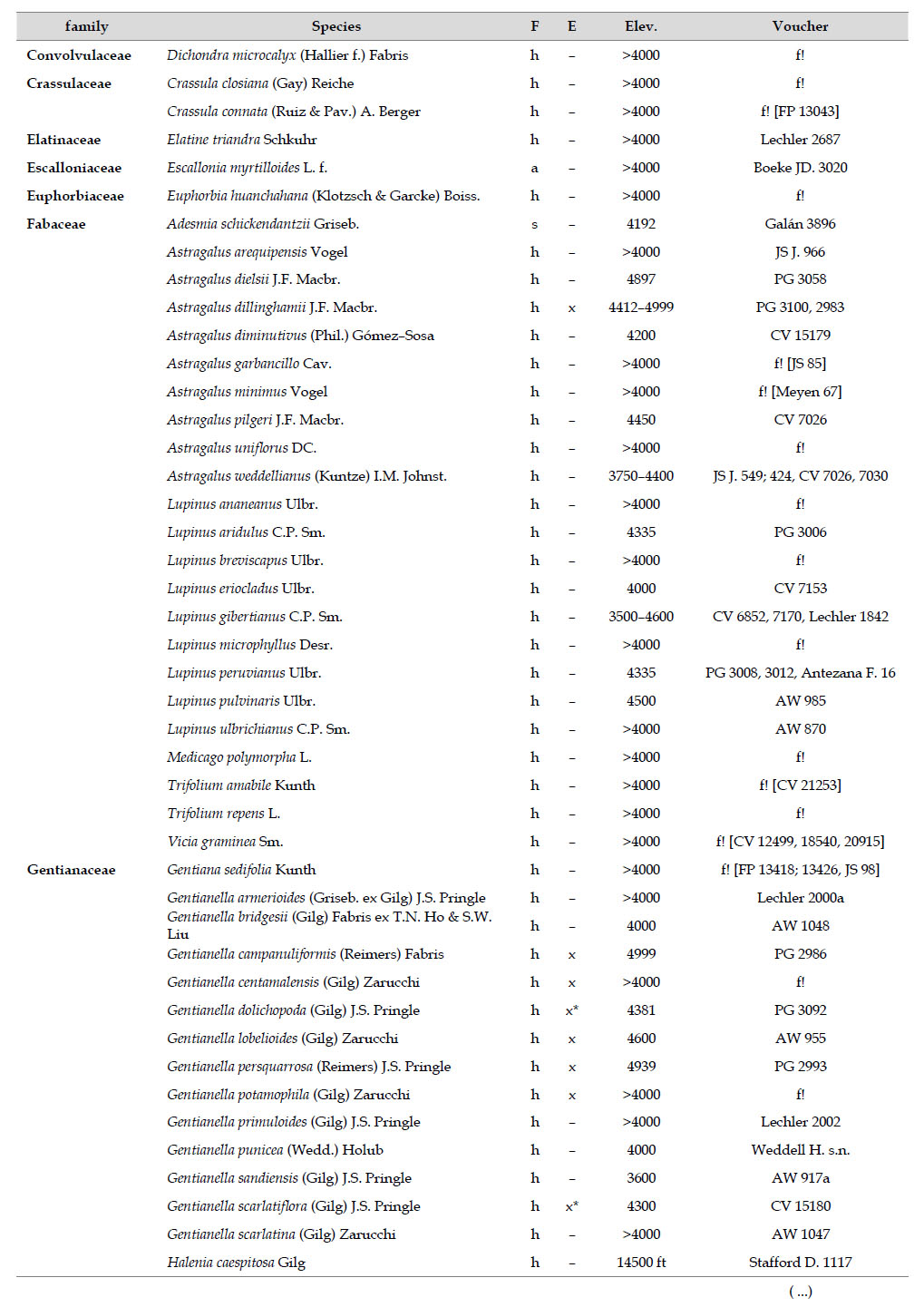

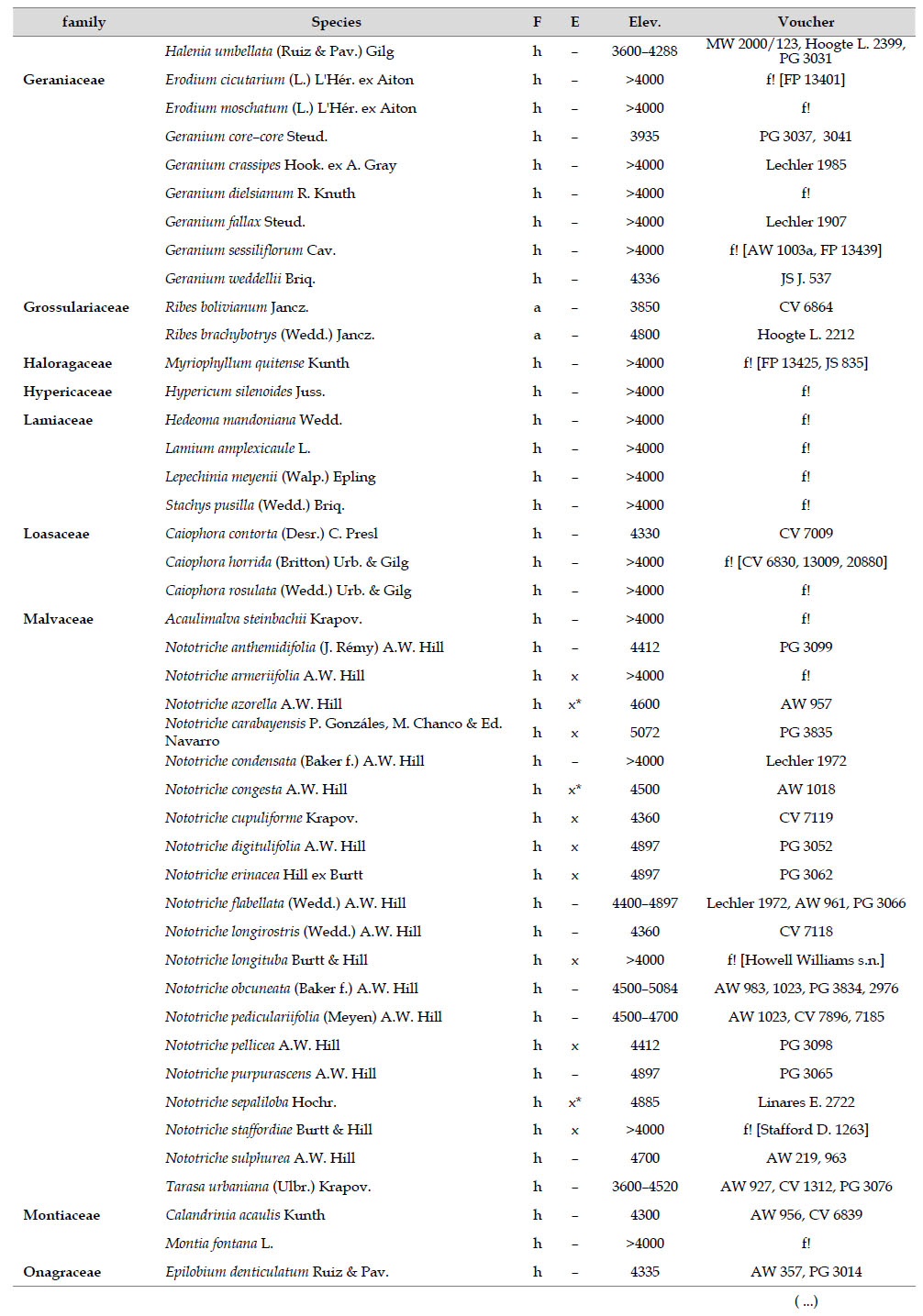

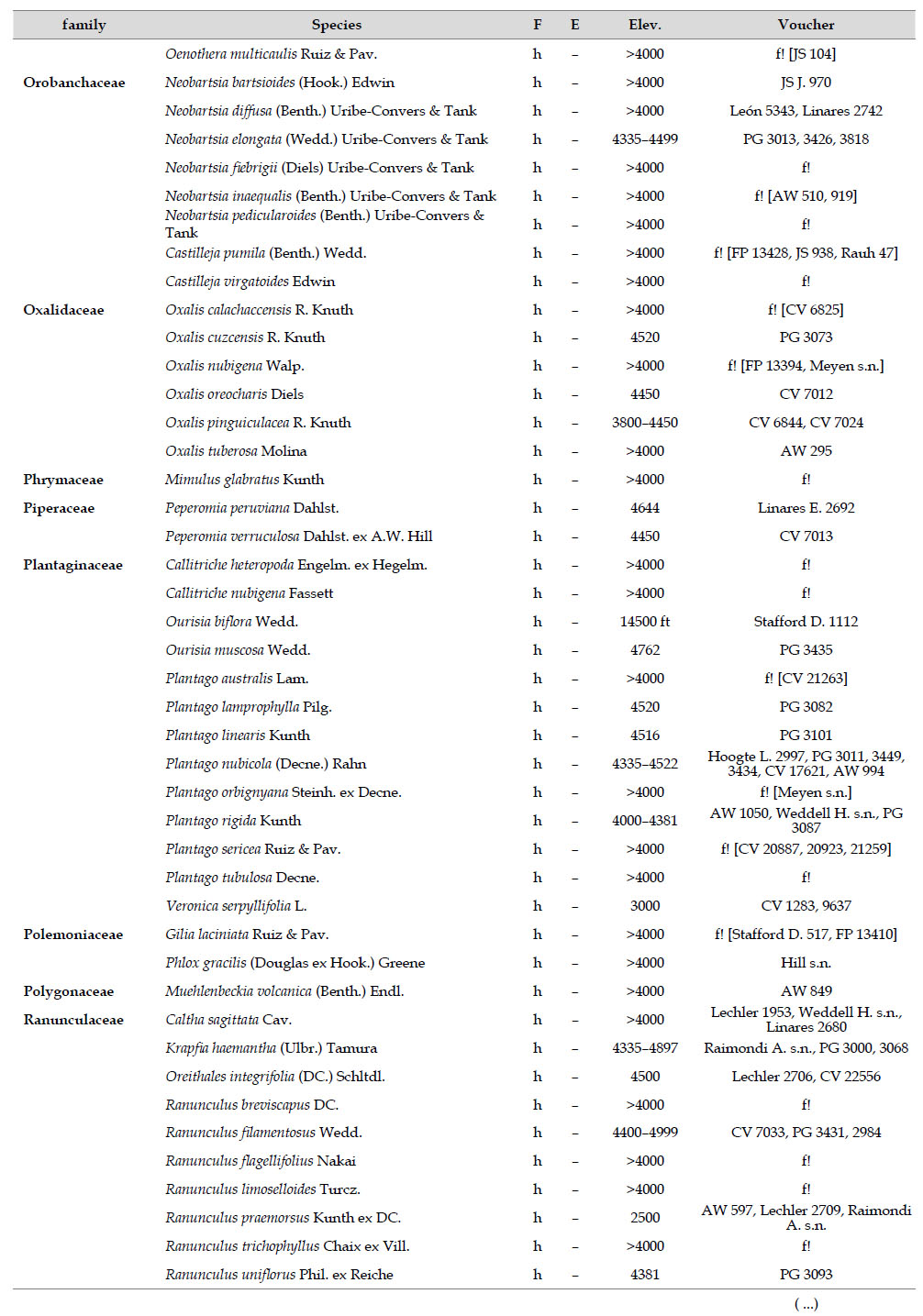

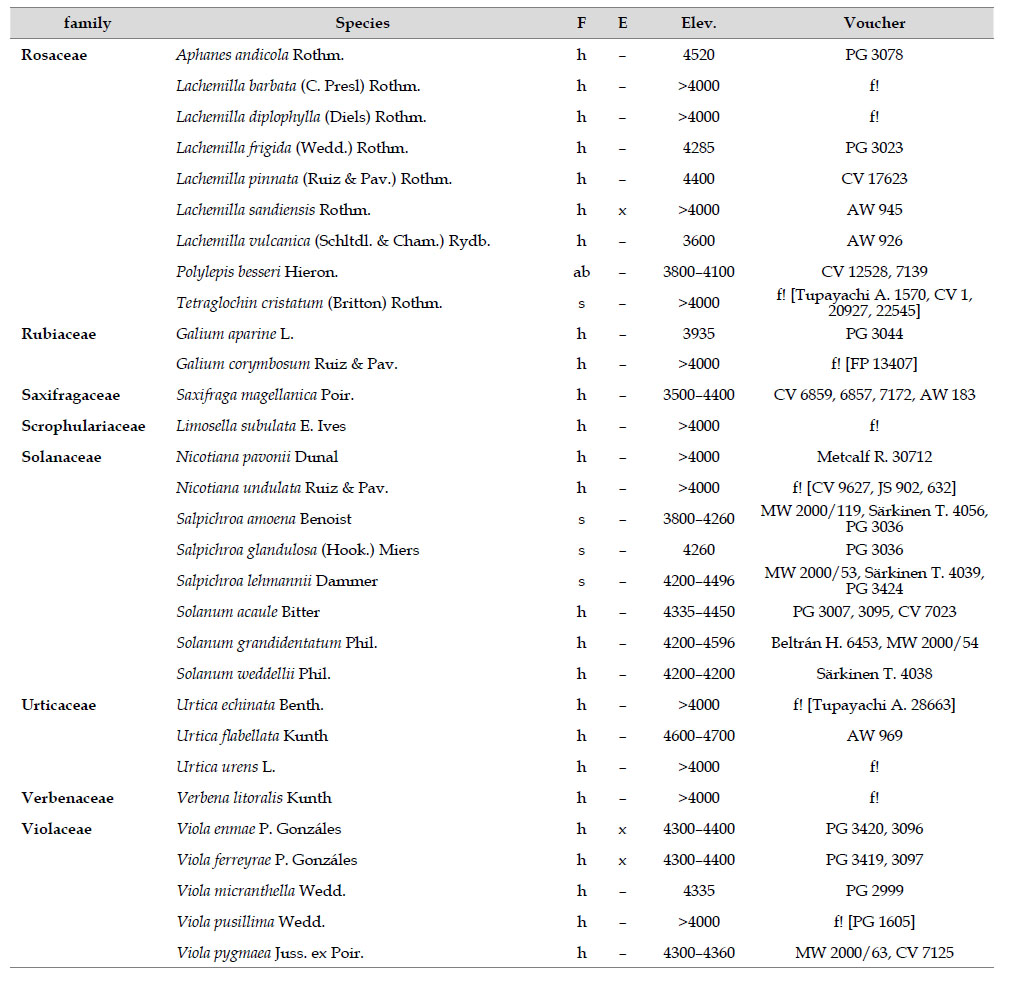

The highest elevations (above 4000 m) of the Carabaya Mountains harbors 506 species of vascular plants (pteridophytes, Gymnospems, Eudicots and Monocots) grouped in 203 genera and 66 families (Table 1; Fig. 2 and Appendix 1). Eudicots were the largest group (with 68.2% of the total registered), and including 69.5% of genera and 71.9% of all species; followed by Monocots with 16.7%, 22.7% and 23.7% respectively for all three main taxonomic categories. Ferns and lycophytes were scarcely represented with only nine families (13.6%), fifteen genera (7.4%) and twenty-one species (4.2%). For these elevations, we found only one species of gymnosperm (Ephedra rupestris).

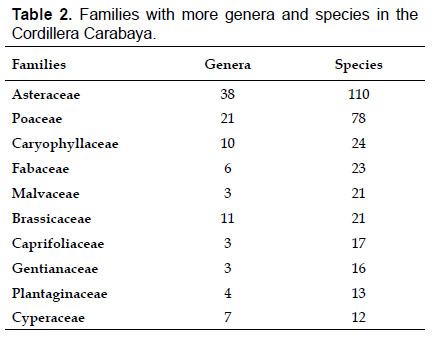

Asteraceae was the most diverse family, with 38 genera and 110 species, followed by Poaceae (21/78), Caryophyllaceae (10/24), Fabaceae (6/23), Malvaceae (3/21), Brassicaceae (11/21), Caprifoliaceae (3/17), Gentianaceae (3/16), Plantaginaceae (4/13) and Cyperaceae (7/12). These ten families include 52% of all genera and 66% of all species registered for Carabaya. Asteraceae and Poaceae together account for 29.1% of the total genera and 37.2% of all species (Table 2). Another 10 families have six to ten species, containing 16.2% of the total taxa registered. Sixty-six percent of the remaining families include five or less number of species: 24 families have between two and five species, containing 13.2% of total taxa, while 22 families are represented by a single species.

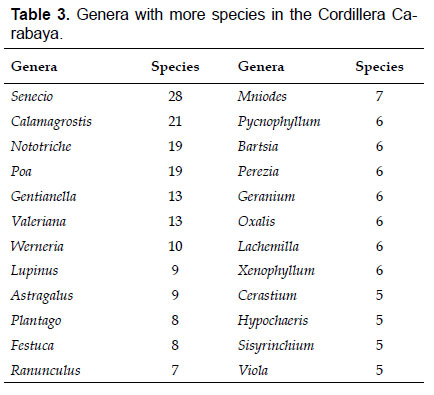

The most diverse genera were Senecio (28 species), Calama grostis (21), Poa (21), Nototriche (19), Gentianella (13), Valeriana (13), Werneria (10), Lupinus and Astragalus with nine species each, Festuca and Plantago with eight species each, Mniodes and Ranunculus with seven each;Geranium, Neobartsia, Oxalis, Perezia, Pycnophyllum, and Xenophyllum with six each; Cerastium, Hypochaeris, Sisyrinchium and Viola with five each (Table 3). The remaining, 62 genera (30.5%), include between two and four species, while 117 genera (57.6%) only have one species.Perennial herbs are the dominant life form with 467 (92.3%) species, these include aquatics, palustrine and terrestrial forms. While woody life forms include 20 species (4%) of subshrubs, 15 (3%) shrubs, three (0.6%) cactus, and one tree (0.2%). (Appendix 1).

Comparison of Carabaya flora with nines sites, including northern Bolivia reveals that Asteraceae and Poaceae remain the most species-rich families. All sites, except Parinacochas, have most of its genera and species (over 50%) included in the same ten families identified in Table 4. Other sites representing specific habitats (periglacial areas, and wetlands), also have the same species-rich families as those found in Carabaya (see also Table 2). The richness of all eight sites of Carabaya is as high as those found in northern Bolivia and Moquegua in southwestern Peru.

Over 91 % of species recorded for Carabaya have an altitudinal range above 4000 m (Append. 1). Plant endemism in the Department of Puno reaches 185 species, and most species are found at the upper limits of our study area (Append. 1).

Discussion

The high Andes is an important biogeographical region, distributed as an archipelago along the mountain range. Its plant species richness is high compared to other mountain ranges, and where past geological changes has allowed expansion and contraction, which may explain current plant composition, diversity and endemism (Sklenář et al. 2013, Hughes & Atchison 2015). Most recent studies have shown the northern Andes, particularly the paramo, as a place of high plant species richness (Sklenář & Balslev 2005, 2007, Cuesta et al. 2017). Our data also demonstrates that other parts of the upper tropical central Andes are as important in terms of plant composition and diversity.

Over 50% of floristic records for the study area are new, particularly for the department of Puno (Brako & Zarucchi 1993, Ulloa Ulloa et al. 2004, Linares et al. 2012). For the flora at high elevations (>4000 m) of Puno, our results have tripled (20 more species) the known number of endemic species. It is worth noting that this department has the highest percentage of rarity (65%) compared to other departments (León et al. 2007). The value of the CDI is lower than the national value of 34 recorded almost 30 years ago (see Toledo & Sosa 1993), and it demonstrates the need for further botanizing. This need is further complicated by pressures of global changes, creating important challenges for plant conservation (Young 2014).

The flora of the Carabaya, at the family level, includes two families (Asteraceae and Poaceae) that contribute significantly to its composition with over a third of species. The predominance of both families is a common pattern in the High Andean flora (Gentry 1993, Cuesta et al. 2017), where these two families can include 30 to 60% of all species in an area (Table 4). In addition, this trend of family oligarchy extends in our study to 18 other families, among them Fabaceae, Caryophyllaceae, Brassicaceae and Malvaceae, which has been shown to be species rich throughout the Puna (Cuesta et al. 2017). Most families, however, are species poor, and they usually represent taxa that originated in temperate areas. Probable explanations of species richness of those few families may include geological history, altitudinal range and different evolutionary paths of mountain ranges within the Andes.

A total of 506 species of vascular plants growing above 4000 m in the Carabaya shows that our floristic results are consistent with those found for other equivalent areas in the tropical high Andes. Species richness in our study area is like those found for Perus jalca (Sánchez 1996). For the Andean highlands of northern Bolivia (Department of La Paz) reported by Jørgensen (2014), total species (737) number is larger than for our study area, which can be explained by representing a flora of a bigger area with more extensive botanizing.

As proposed by Sklenář et al. (2013), floristic similarities in the Andes are higher in areas of geographical proximity. The undoubted geophysical connection of the Carabaya and the Bolivian Apolobamba Mountains, may suggest a close floristic relationship with Bolivias high Andean flora. We found nearly half of all vascular plants (262 species) registered for the Cara-baya Mountain also occur in the Andean region of Bolivia. At the family level, eight families Asteraceae, Poaceae, Fabaceae, Caryophyllaceae, Brassicaceae, Malvaceae, Cyperaceae and Apiaceae are part of the most diverse families in both study areas (Table 4). However, there are thirteen families (Araceae, Araliaceae, Basellaceae, Bromeliaceae, Calyceraceae, Ericaceae, Dennstaedtiaceae, Frankeniaceae, Polygalaceae, Portulacaceae, Ruppiaceae, Schoepfiaceae and Selaginellaceae) that have not yet been collected in the Carabaya. While another four families (Asparagaceae, Escalloniaceae, Convolvulaceae and Berberidaceae) have not yet been recorded for the Bolivian flora at similar altitudes

There are also 35 genera and 244 species in Carabaya not registered for Bolivia, the largest of these differences are present in genera such asSenecio (with 15 species), Nototriche (13), Valeriana, Calamagrostis and Gentianella (with 9 species each), Poa (7), Xenophyllum (6), Lupinus, Neobartsia and Pycnophyllum (with 5 species each). Most of these species (186) are endemic to Peru, and they occupy the highest part of the study area.

A comparison with the species composition of Cordillera Vilcanota, located to the north of our study area, reveals that 46% of the species registered there have not yet been found in Carabaya. Studies in Vilconata have emphasized areas covered by Polylepis forest that were not included for Carabaya. Still, excluding those species of Polylepis forests, a third of species of the flora of Vilcanota have not been recorded in Carabaya.

At a more local scale, we found that Carabaya has similar number of taxa as those reported for an upper basin in Moquegua (Montesinos-Tubée 2011, 2012; (Table 4) on the Pacific Basin. Seven plant families: Asteraceae, Poaceae, Brassicaceae, Caryophyllaceae, Fabaceae, Malvaceae and Plantaginaceae are part of the most diverse families in both study areas (Table 4). Two families Asteraceae and Poaceae have also equal representation for both sites, with 22%, and 15% for Carabaya, and 25% and 9% for Tambo–Ichuña respectively. However, some differences at the family level are present due to the altitudinal extent of our study (40005300 m) vs. those of Montesinos-Tubée (3400–4850 m). For example Cyperaceae and Caprifoliaceae are among the top ten most diverse families in the Carabaya, while Solanaceae and Cactaceae are for Moquegua (Montesinos-Tubée 2011, 2012). These differences may also reflect floristic differences between western and southern ranges.

The top ten most diverse families have also been reported by Cano et al. (2010, 2011) for periglacial sites with cryoturbated soils in Ancash (Cordillera Blanca) and Ayacucho-Huancavelica (Apacheta), reaching 79 and 87% respectively (Table 4). However, these families decrease their diversity at lower elevation (Flores et al. 2005, Arteta et al. 2006, Roque & Ramírez 2008), or when the richness is restricted to specific vegetation formations such as wetlands (Ruthsatz 2012, Valencia et al. 2013).

For the flora of Carabaya, the most abundant genera in terms of species richness were Senecio, Calamagrostis, Nototriche and Poa; this taxonomic composition towards a few highly diverse genera has been explained due to the high degree of a recent local speciation driven by geographic isolation between high alpine continental islands or complexes (Sklenář & Balslev 2005, Sklenář et al. 2013). In addition, these same genera are the most abundant in terms of vegetation cover (Cuesta et al. 2017).

A perennial life form is obviously the dominant plant type in the high Andes. This life form includes most species in plant lineages with rapid diversification and radiation in the Andes, such as Lupinus, Nototriche, Pycnophyllum, Senecio and others. Hughes and Atchison (2015) suggest that perenniality could have played a general role as a key adaptation, enabling lineages to take advantage of ecological opportunities associated with the recent availability of alpine habitats to rapidly diversify as was observed in Lupinus (Drummond et al. 2012). In this study, half of the Carabaya flora has longer life cycles as Perennials represented by herbaceous forms. However, a more detailed exam might allow recognition of other types such as rosettes, mats, and cushions.

Because of the availability of data from local, regional and country floras further comparisons are now feasible. The similarities in floristic composition and richness confirm the importance of the tropical Andes as global hotspot of plant diversity. Differences in flora sizes, especially between Caraba-ya and its closest neighboring sites, demonstrate the need of extending botanical exploration in Peru, and for the detailed recording in different types of habitats. Plant collections are still needed in many areas to fully understand the patterns of species diversity, and characteristics of their populations. As it can be found in the results of this study, several species have not been found since their discovery (e.g., Alsine rupestris Muschl., Nototriche cupuliforme Krapov. and Nototriche erinacea A.W. Hill). The high number of species (>91%) with its lower limits above 4000 m underscores the importance of the high Andes for conservation. This is even more important today in the Peruvian high Andes, where climatic conditions and human induced changes play an important role for impacting them (see Young 2014). Threats originate directly by overlapping competing human activities such as mining, fire, agriculture, landslides, erosion and other land uses. In addition, climate change associated to these anthropic influences are leading to the fragmentation of habitats and therefore, the loss of species survival and diversity, and possible mountaintop extinctions. Finally, it should be mentioned that many taxonomic studies are still pending to fully understand the biodiversity of the fascinating Andean highlands.

Acknowledgements

We thank Daniel Montesinos for providing valuable comments on the manuscript. We also thank Kenneth R. Young for his comments and critical review of this manuscript. Curators of all the herbaria cited are thanked for making available their plant collections. We also acknowledge all the people who made the botanical collections in the studied region.

Declaration of authorship

The authors state that all participated in the development of the work. PG, BL, AC and PJ: did sampling, drafting of the manuscript, and data analysis. PG and BL: did interpretation and preparation of the final version. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Literature cited

Al-Shehbaz I.A., A. Cano, H. Trinidad & E. Navarro. 2013. New Species of Brayopsis, Descurainia, Draba, Neuontobotrys and Weberbauera (Brassicaceae) from Peru. Kew Bulletin 68 (2):219–231. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12225-013-9447-z [ Links ]

Al-Shehbaz I.A., P. Gonzáles & A. Cano. 2015a. Englerocharisblanca–leoniae (Brassicaceae), a new species from Puno,Peru. Harvad Papers in Botany 20(1):1–4. doi: https://doi.org/10.3100/hpib.v20iss1.2015.n1 [ Links ]

Al-Shehbaz I.A., P. Gonzáles & A. Cano. 2015b. Weberbauera incisa (Brassicaceae), a new species from southern Peru. Novon 24(1):6–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.3417/2015003 [ Links ]

Angiosperm Phylogeny Group IV. 2016. An update of the AngiospermPhylogeny Group classification for the orders and families offlowering plants: APG IV. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 181:1–20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.10958339.2009.00996.x [ Links ]

Argollo J., M. Fornari, G. Herail, V. Miranda & G. Viscarra. 1987. Estratigrafía de los depósitos glaciares en la Cordillera de Apolobamba (Bolivia) y su asociación con mineralizaciones auríferas. Décimo Congreso Geol. Argentino, San Miguel de Tucumán, Actas II:67-69. [ Links ]

Argollo J. & M.H. Iriondo. 2008. El cuaternario de Bolivia y regiones vecinas. Museo Provincial de Ciencias Naturales Florentino Ameghino. Santa Fe, Argentina. [ Links ]

Arteta M., M. Corrales, C. Dávalos, A. Delgado, F. Sinca, L. Hernani & J. Bojórquez. 2006. Plantas vasculares de la bahía de Juli, lago Titicaca, Perú. Ecología Aplicada 5(1–2):29–36. [ Links ]

Ballard H.E. & H.H. Iltis. 2012. Viola lilliputana sp. nov. (Viola sect. Andinium, Violaceae), one of the world's smallest violets, from the Andes of Peru. Brittonia 64(4):353–358. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12228-012-9238-0 [ Links ]

Beniston M. 1994. Mountain environments in changing climates.Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Bridson D. & L. Forman. 1992. Herbarium Handbook. Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew. [ Links ]

Brako L. & J. Zarucchi. 1993. Catalogue of the flowering plants and gymnosperms of Peru. Monographs in Systematic Botany from the Missouri Botanical Garden 45:1–1286. [ Links ]

Cano A., W. Mendoza, S. Castillo, M. Morales, M.I. La Torre, H. Aponte, A. Delgado, N. Valencia & N. Vega. 2010. Flora yvegetacion de suelos crioturbados y habitats asociados en laCordillera Blanca, Ancash, Peru. Revista Peruana de Biologia17(1):095–0103. doi: https://doi.org/10.15381/rpb.v17i1.56 [ Links ]

Cano A., A. Delgado, W. Mendoza, H. Trinidad, P. Gonzáles, M.I. La Torre, M. Chanco, H. Aponte, J. Roque, N. Valencia & E. Navarro. 2011. Flora y vegetación de suelos crioturbados y hábitats asociados en los alrededores del Abra Apacheta, Ayacucho–Huancavelica (Perú). Revista Peruana de Biología 18(2):169–178. doi: https://doi.org/10.15381/rpb.v18i2.224 [ Links ]

Cerrate E. 1969. Manera de preparar plantas para el herbario. Museo de Historia Natural, Serie de Divulgación, N°1. [ Links ]

Conde-Álvarez C. & S. Saldaña–Zorrilla. 2007. Cambio climático en América Latina y el Caribe: Impactos, vulnerabilidad y adaptación. Revista Ambiente y Desarrollo 23 (2):23–30. [ Links ]

Cuesta F., P. Muriel, L. D. Llambí, S. Halloy, N. Aguirre, S. Beck, J. Carilla, R. I. Meneses, S. Cuello, A. Grau, L. E. Gámez, J. Irazábal, J. Jácome, R. Jaramillo, L. Ramírez, N. Samaniego, D. Suárez-Duque, N. Thompson, A. Tupayachi, P. Viñas, K. Yager, M. T. Becerra, H. Pauli & W. D. Gosling. 2017. Latitudinal and altitudinal patterns of plant community diversityon mountain summits across the tropical Andes. Ecography40:1–14. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.02567 [ Links ]

Drummond C. S., R. J. Eastwood, S. T. S. Miotto, & C. E. Hughes. 2012. Multiple continental radiations and correlates ofdiversification in Lupinus (Leguminosae): Testing for Key innovation with incomplete taxon sampling. SystematicBiology 61(3): 443-460. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syr126 [ Links ]

Flores M., J. Alegría, & A. Granda. 2005. Diversidad florística asociadaa las lagunas andinas Pomacocha y Habascocha, Junín, Perú.Revista Peruana de Biología 12(1): 125–134. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/rpb.v12i1.2366 [ Links ]

Fort M. 2015. Impact of climate change on mountain environment dynamics. Journal of Alpine Research / Revue de géographiealpine 103-2. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4000/rga.2877 [ Links ]

Galán de Mera A., B. Del Monte, E.M. Mendoza, E. Linares, J. Campos, & J.A. Vicente. 2014. Las comunidades vegetales relacionadas con los procesos criogénicos en los Andesperuanos. Phytocoenologia 44(1–2):121–161. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1127/0340-269X/2014/0044-0576 [ Links ]

Gentry A.H. 1993. Overview of Peruvian Flora. In: Brako L, ZarucchiJ, Catalogue of the Flowering Plants and Gymnosperms of Peru. Monographs in Systematic Botany from the Missouri Botanical Garden 45:1–1286. [ Links ]

Gonzáles P., E. Navarro, M. Chanco & A. Cano. 2015. Nototriche carabayensis (Malvaceae), una especie nueva de los Andes de Perú. Darwiniana 3(1):1–6. [ Links ]

Gonzáles P., A. Cano, I. Al–Shehbaz, D.W. Ramírez, E. Navarro, H. Trinidad & M. Cueva. 2016. Doce nuevos registros de plantas vasculares para los Andes de Perú. Arnaldoa 23(1): 159–170. [ Links ]

Gonzáles P. & A. Cano. 2016. Two new species of Viola (Violaceae) named in honor preceding Peruvian botanists. Phytotaxa 283(1): 083–090. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.283.1.6 [ Links ]

Hughes C.E. & G.W. Atchison. 2015. The ubiquity of alpine plant radiations: from the Andes to the Hengduan Mountains. NewPhytologist 207:275–282. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/nph.13230 [ Links ]

Jørgensen P.M., C. Ulloa Ulloa, B. León, S. León-Yánez, S.G. Beck, M. Nee, J.L. Zarucchi, M. Celis, R. Bernal & R. Gradstein. 2011. Regional patterns of vascular plant diversityand endemism. 192203. IN: S.K. Herzog, R. Martinez, P.M. Jørgensen & H. Tiessen (Eds.). Climate Change and Biodiversity in the Tropical Andes. SCOPE, MacArthur Foundation & IAI.

Jørgensen P. M., M.H. Nee & S.G. Beck. (eds.) 2014. Catálogo de las plantas vasculares de Bolivia, Monogr. Syst. Bot. Missouri Bot. Gard. 127(1–2): i–viii, 1–1744. Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis.

Kohler T., A. Wehrli, M. Jurek. (eds.). 2014. Mountains and climate change: A global concern. Sustainable Mountain Development Series. Bern, Switzerland, Centre for Development andEnvironment (CDE), Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and Geographica Bernensia.

Macbride J.F. et al. 1936 and next. Flora of Peru. Field Museum of Natural History, Botanical Series, Chicago. [ Links ]

León B., J. Roque, C. Ulloa Ulloa, N. Pitman, P.M. Jørgensen & A. Cano. 2007. El libro rojo de las especies endémicas del Perú.Revista Peruana de Biologia, Número especial 13(2):1–971. [ Links ]

Linares E., J.E. Campos & A. Galán de Mera. 2012. Nuevas adiciones a la flora del Perú, VI. Arnaldoa 19(1):37–45. [ Links ]

Linares E., J.E. Campos, J.A. Vicente & A. Galán de Mera. 2015. Adesmia schickendantzii (Fabaceae, subgen. Acanthadesmia),novedad para la flora del Perú. Acta botánica malacitana (40):206–208. [ Links ]

Markham A., N. Dudley & S. Stolton. 1993. Some like it hot: climate change, biodiversity and the survival of species. WWF–International, Gland. [ Links ]

Montesinos-Tubée D.B. 2011. Diversidad florística de la cuenca alta del río Tambo–Ichuña (Moquegua, Perú). Revista Peruana deBiologia 18(1):119–132. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/rpb.v18i1.156 [ Links ]

Montesinos-Tubée D.B. 2012. Lista anotada de nuevas adiciones para la flora andina de Moquegua, Perú. Revista Peruana de Biologia 19(3):303–312. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/rpb.v19i3.1045 [ Links ]

Montesinos-Tubée D.B., A.M. Cleef & K.V. Sýkora. 2015a. ThePuna vegetation of Moquegua, South Peru: Chasmophytes, grasslands and Puya raimondii stands. Phytocoenologia 45(4):365–397. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1127/phyto/2015/0006 [ Links ]

Montesinos-Tubée D.B., P. Gonzáles & E. Navarro. 2015b. Senecio canoi (Compositae), a new species of the Andes of Peru. Anales Jardín Botanico de Madrid 72(2):1–4. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/ajbm.2409 [ Links ]

Ospina J.C., S.P. Sylvester & M.D.P.V. Sylvester. 2016. Multivariate analysis and taxonomic delimitation within the Festuca setifolia complex (Poaceae) and a new species from the Central Andes. Systematic Botany 41(3):727-746. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1600/036364416X692398 [ Links ]

Pauli H., M. Gottfried & G. Grabherr. 2003. Effects of climate changeon the alpine and nival vegetation of the Alps. Journal of Mountain Ecology 7 (Suppl.):9–12. [ Links ]

Pauli H., M. Gottfried, K. Reiter, C. Klettner & G. Grabherr. 2007. Signal of range expansions and contractions of vascularplants in the high Alps: Observations (1994–2004) atThe GLORIA Master Site Schrankagel, Tyrol, Austria. Gobal Change Biology 13:147–156. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01282.x [ Links ]

Ruthsatz B. 2012. Vegetación y ecología de los bofedales altoandinos de Bolivia. Phytocoenologia 42:133–179. doi: https://doi.org/10.1127/0340-269X/2012/0042-0535 [ Links ]

Roque J. & E.K. Ramírez. 2008. Flora vascular y vegetación de la laguna Parinacochas y alrededores (Ayacucho, Perú). Revista Peruana de Biología 15(1):105–110. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/rpb.v15i1.1677 [ Links ]

Sánchez V.I. 1996. Aspectos florísticos de la jalca y alternativas de manejo sustentable. En: Anales del Simposio Estrategias para Bioconservación en el Norte del Perú. Arnaldoa Ed. Esp. 4(2): 25–62. [ Links ]

Sklenář P. & H. Balslev. 2005. Superpáramo plant species diversity andphytogeography in Ecuador. Flora - Morphology, Distribution, Functional Ecology of Plants, 200(5):416–433. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.flora.2004.12.006 [ Links ]

Sklenář P. & H. Balslev. 2007. Geographic flora elements in theEcuadorian superpáramo. Flora - Morphology, Distribution, Functional Ecology of Plants, 202(1):50-61. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.flora.2006.03.002 [ Links ]

Sklenář P., I. Hedberg & A. M. Cleef. 2014. Island biogeography of tropical alpine floras. Journal of Biogeography 41:287–297.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jbi.12212 [ Links ]

Sylvester S.P., D. Quandt, L. Ammann & M. Kessler. 2016. The worldssmallest Campanulaceae: Lysipomia mitsyae, sp. nov. Taxon65(2):305–314. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.12705/652.7 [ Links ]

Sylvester S.P., R.J. Soreng, P. M. Peterson & M.D.P.V. Sylvester. 2016.An updated checklist and key to the open-panicled speciesof Poa L. (Poaceae) in Peru including three new species, Poa ramoniana, Poa tayacajaensis, and Poa urubambensis. PhytoKeys 65:57–90. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3897/phytokeys.65.7024 [ Links ]

Thompson L.G., E. Mosley-Thompson, M.E. Davis, P.N Lin, K. Henderson & T.A. Mashiotta. 2003. Tropical glacier and ice core evidence of climate change on annual to millennial time scales. Climate Change 59:137–155. doi: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024472313775 [ Links ]

Thompson L.G., E. Mosley-Thompson, H. Brecher, M. Davis, B.León, D. Les, L. Ping-Nan, M. Tracy & K. Mountain. 2006.Abrupt tropical climate change: Past and present. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103(28):10536–10543. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0603900103 [ Links ]

Thompson L.G., E. Mosley-Thompson, M.E. Davis, V.S. Zagorondnov; I.M. Howat, V.N. Mikhalenko & P.N. Lin. 2013. Annually resolved ice core records of tropical climate variability over past ~1800 years. Science 340(6135):945–950. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1234210 [ Links ]

Toledo V.M. & V. Sosa. 1993. Floristics in Latin America and the Caribbean: An evaluation of the numbers of plant collectionsand botanists. Taxon 42:355–364. [ Links ]

Tovar O. 1993. Las gramíneas (Poaceae) del Perú. Ruizia 13:9–474. [ Links ]

Tupayachi A. 2005. Flora de la Cordillera Vilcanota. Arnaldoa12(1–2):126–144. [ Links ]

Ulloa Ulloa C., J.L. Zarucchi & B. León. 2004. Diez años de adiciones a la flora del Perú. Arnaldoa (edición especial):7–242. [ Links ]

Valencia N., A. Cano, A. Delgado, H. Trinidad & P. Gonzáles. 2013. Composición y cobertura de la vegetación de los bofedales enun macrotransecto este–oeste, en los Andes centrales del Perú pp. 278–293 In A. Alonso, F, Dallmeier & G. Servat. (Ed.), Monitoreo de la biodiversidad: lecciones de un megaproyectotransandino. Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press. USA. [ Links ]

Weberbauer A. 1945. El Mundo Vegetal de los Andes Peruanos. Ministerio de Agricultura, Lima. Lumen S.A. [ Links ]

Young K. R. 2011. Introduction to Andean Geographies. pp. 128-137.In: S. K. Herzog et al. Climate Change and biodiversity in the tropical Andes. IAI. [ Links ]

Young K. R. 2014. Ecology of land cover change in glaciated tropical mountains. Revista peruana de Biologia 21:259–270. doi: https://doi.org/10.15381/rpb.v21i3.10900 [ Links ]

Young K. R., C. Ulloa Ulloa, J. Luteyn & S. Knapp. 2002. Plant evolution and endemism in Andean South America: An Introduction. Botanical review 68(1):4–21. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1663/0006-8101(2002)068[0004:PEAEIA]2.0.CO;2 [ Links ]

* Corresponding author

E-mail Paúl Gonzáles: pgonzalesarce@hotmail.com

E-mail Asunción Cano: acanoe@unmsm.edu.pe

E-mail Blanca León: leon@austin.utexas.edu

E-mail Peter M. Jørgensen: peter.jorgensen@mobot.org

Presentado: 26/01/2018

Aceptado: 03/06/2018

Publicado online: 25/09/2018

NOTAS