INTRODUCTION

Glomus tumors are benign mesenchymal neoplasms that originate in modified smooth muscle cells of the glomus body. They are composed of varying proportions of glomic cells, blood vessels, and smooth muscle. Therefore, depending on the predominant component, they can be classified as a solid glomus tumor (few vascular structures and few muscle cells), glomangioma (with a prominent vascular component), or glomangiomyoma (with predominant vascular and smooth muscle cells). The most common variant is solid tumor (75%), followed by glomangioma (20%) and glomangiomyoma (5%).1 Diagnosis of glomus tumors is difficult without a careful histopathological analysis of biopsies, as glomus tumors resemble other neoplasms such as hemangiomas, adnexal tumors, myopericytoma and myofibromatosis.1 Glomus tumors usually occur in areas where there is a high concentration of glomus bodies, such as subungual regions and the deep dermis of the distal extremities. In addition to the deep dermis, glomus tumors have been described in almost every other part of the body, rarely including the stomach.1

Vascular tumors account for less than 2% of all benign tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Gastric glomus tumors account for approximately 1% of these. Gastrointestinal glomus tumors occur almost always in the stomach, arising in the intramuscular layer. These tumors are similar to peripheral glomus tumors but are different from other stomach neoplasms, such as epithelioid gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) and adenocarcinoma, which are more common.2-4 The frequency of gastric glomus tumors is estimated to be 100 times lower than that of GIST.5 Treatment of glomus tumors usually involves excision and they have a good postoperative prognosis; they rarely become malignant.3 Nonetheless, gastric glomus tumors are usually symptomatic when they become large enough and are likely to cause epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, hematemesis, and/or melaena.6

Correct diagnosis of gastric glomus tumors is challenging because these tumors are like more common neoplasms of the stomach, cause symptoms associated with ulcers and Helicobacter pylori infection and cannot be differentiated through imaging or observation. Therefore, histopathology and a high index of clinical radiological suspicion are necessary to suspect and diagnose this unusual cancer.

We present a case of a 52-year-old Peruvian woman who was initially diagnosed with a gastrointestinal stromal tumor that was later shown to have an antral glomangioma.

CASE REPORT

In June 2023, a 52-year-old Peruvian woman from Piaján, Ascope, La Libertad, Peru was seen in a private clinic. She complained of gastric symptoms of upset stomach, early satiety, and belching lasting for 10 months. Her medical history included hypertension and diabetes, which were treated with irbesartan and metformin. She was also diagnosed with H. pylori infection by antral biopsy and was also taking magaldrate, simethicone, mosapride, and pantoprazole for her gastric symptoms. Her father and paternal aunt were diagnosed with prostate and breast cancer.

In June 2023, an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed a crescent-shaped subepithelial lesion located between the major and minor curves of the anterior face of the antrum. It obstructed approximately 70% of the pylorus. Histology revealed diffuse moderate chronic gastritis with intestinal metaplasia.

Because the lesion was subepithelial, an endoscopic ultrasound (echo-endoscopy) was performed approximately one month later to further characterize the lesion. A subepithelial lesion measuring 51x38 mm was observed in some sections from the 4th layer. It was heterogeneous with hyperechogenic sections, which suggested calcifications. A biopsy of the lesion was performed using an echography-guided needle. Cytological analysis revealed spindle cells with no apparent atypia of neoplastic or mesenchymal origin. Immunocytochemical analysis of the biopsied cells gave positive results for antibody to CD117 and were 5% positive to antibody for Ki 67.7 They were not reactive to the active alpha oestrogen receptor. This result suggests a stromal gastrointestinal tumor, as approximately 90% of cases are positive for CD117.8

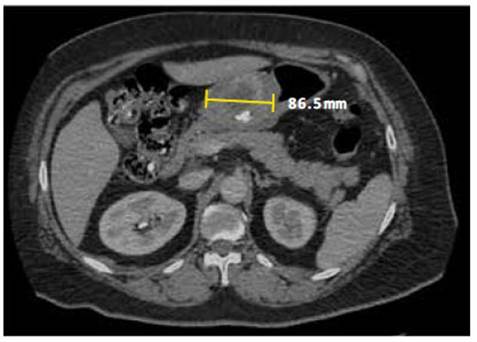

With these results, the patient was referred to the Oncologic Surgery department of the Hospital EsSalud de Alta Complejidad Virgen de la Puerta, where an abdominal and pelvic tomography with contrast and blood analysis were completed. Tomography largely confirmed the endoscopic observations (Figure 1). A slightly distended stomach, diffuse liver disease, and mural thickening at the level of the pyloric canal were observed. The thickening shows enhancement with contrast and some partial calcification. The results of the blood analysis were mostly unremarkable, except for a slightly decreased prothrombin time and slightly elevated alanine aminotransferase activity. Physical examination revealed ECOG level 1 and no peripheral lymphadenopathy. The abdomen was globulous, soft, and depressible with superficial tenderness. No palpable masses were perceived. Together, these results lead to an initial diagnosis of GIST, and the patient was recommended for surgery to remove the tumor.

Figure 1 Tomography of abdomen and pelvis. The stomach is slightly distended; there is a mural thickening at the level of the pyloric canal, which shows enhancement with the contrast substance, as well as some parietal calcifications.

Surgery consisted of an exploratory laparotomy, D0 subtotal gastrectomy, and a Hofmeister-Finsterer ansioperistaltic transmesocolic anastomosis with placement of a Blake drain and nasojejunal tube. The surgical findings included an open cavity, a soft, rounded, and mobile lesion approximately 6 x 5 cm located at the gastric curvature that does not retract into the serous membrane upon pressure (Figure 2). One lymph node in group 4 had a palpable enlargement. The liver had smooth edges, no peritoneal implants were observed, and the rest of the abdominal organs were normal without secondary lesions.

Figure 2 Surgical Specimen. Anterior view of the surgically removed antrum and omentum, showing a tumor on the anterior side of the antrum, with a rounded, regular, exophytic appearance.

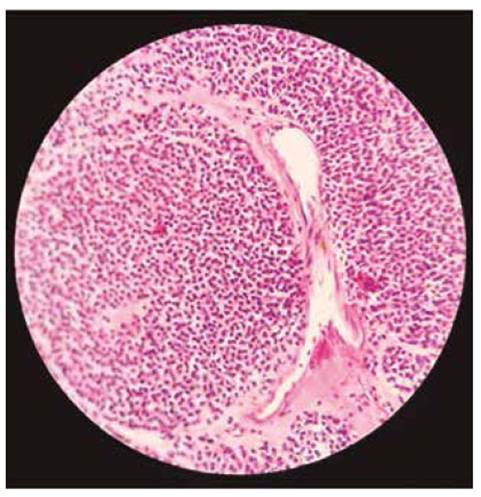

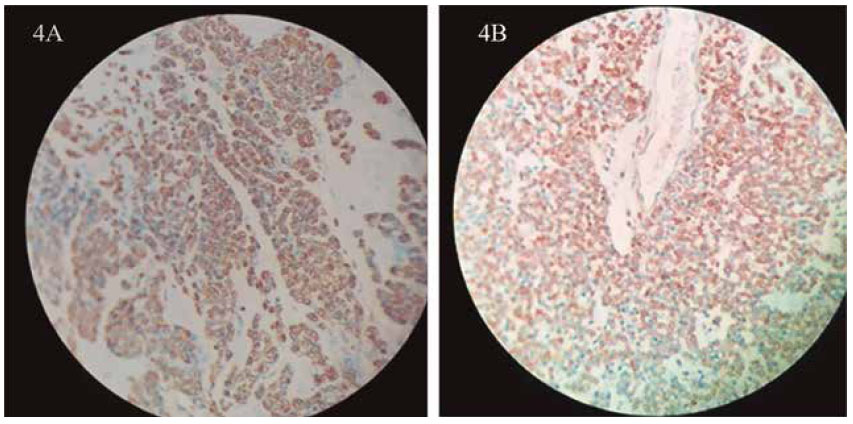

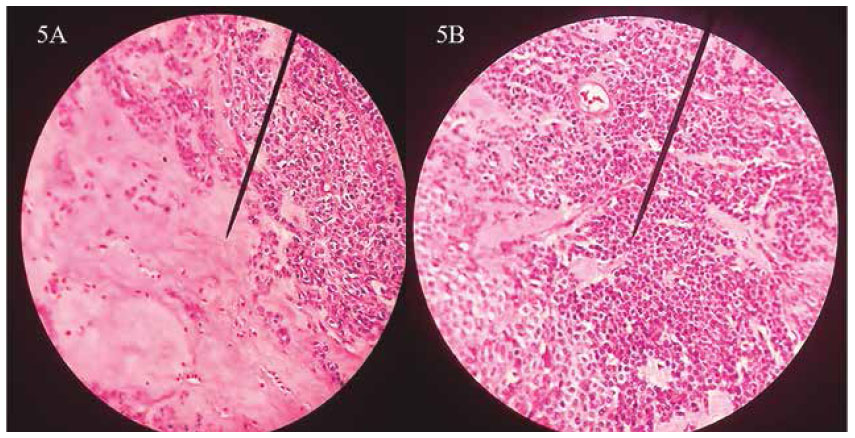

Histopathology of the tumor revealed that it had a size of 4 cm, and mild nuclear grade (Figure 3). Neither necrosis nor perineural invasion was evident, but lymphovascular invasion was. Surgical edges were free, and no lymph nodes (0 of 19) were positive for neoplasm. Immunohistochemistry results were: cKIT (CD117) negative, CD34 negative, alpha actin positive, S-100 negative, calponin positive, desmin negative, EMA negative, vimentin positive, focal synaptophysin (-/+), chromogranin negative, CD31 negative, PK negative, LCA (CD45) negative, Ki67 approximately 1%, caldesmon positive, and the glomus cells shows as rounded shaped, pale cytosol and round to oval-shaped nuclei (Figures 4 and 5). Histomorphology and immunohistochemistry of 'the excised piece favour diagnosis of glomangioma over gastrointestinal stromal tumor.3,9-12

Figure 3 Haematoxylin and eosin (40x) micrograph of the tumor. The tumor consists mainly of small, rounded, well-defined cells, arranged around slightly dilated vessels and low mitotic activity.

Figure 4 Immunohistochemistry. A. Smooth muscle actin stain of the surgical specimen (40x) revealing a positive result. B. Calponin stain of the surgical specimen (40x) revealing a positive result.

Figure 5 Haematoxylin & Eosin (40x). A. Glomus cells located at the right side and hyalinized stroma at the left side. B. The glomus cells show as rounded shaped, uniforms, round to oval-shaped nuclei and pale cytosol.

In the postoperative period, nutritional therapy with polymeric isotonic nutrients was initiated through the nasojejunal tube placed during surgery. Subsequently, there was a progression to oral feeding, but this was discontinued due to stenosis caused by inflammation at the site of the gastrojejunal anastomosis, which was resolved with a one-week course of corticosteroids. The patient was discharged from the hospital in October 2023 with good tolerance to oral feeding. As of November 2023, she is receiving treatment for her H. pylori infection under the care of a gastroenterologist, which consists of esomeprazole, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin. Additionally, she continues to have follow-ups in the oncology department.

DISCUSSION

Glomus tumors are benign tumors of glomic cells, which are modified smooth muscle cells located in the walls of the Sucquet-Hoyer canals (arteriovenous anastomoses or shunts), whose function is to regulate skin temperature by regulating blood flow. Glomus tumors are usually found in the peripheral soft tissues, but can arise elsewhere, including the stomach or intestines, where they can cause acute or chronic bleeding, which results more frequently in melena than haematemesis. Other ulcerlike symptoms are frequent. The tumor may also cause gastric perforation or be symptom-free.1,10,11

In this case, the tumor caused early satiety and gastric discomfort due to its antral location. The patient did not have anaemia, gastric perforation, or bleeding. Therefore, her symptoms were nonspecific, making additional analysis necessary for diagnosis.

Diagnosis of gastric glomus tumors is difficult due to nonspecific symptoms, similarity to other neoplasms, and subepithelial nature. Endoscopic biopsy is not particularly useful in these cases because the tumor resides beyond the reach of the biopsy and other imaging technologies reveal solitary hypervascularized lesions with an average side between 1 and 4 cm, which resemble more common neoplasms like GIST or lymphoma.13

Standard treatment for gastric glomus tumors is surgical excision consisting of complete resection with free margins of the tumor without lymphonodectomy, according to several case reports. 4,5,14-16 In our case, the patient was treated by surgery. As the lesion was circumferential, antral and stenosing, the patient underwent a partial gastrectomy with a proximal surgical margin measuring 4.5 x 3.5 cm and a distal surgical border measuring 2.5x2 cm. The affected lymph nodes only corresponded to the antral area, specifically to groups 3b, 5, 6 and 4d, which were resected together to keep the specimen intact and prevent its rupture. The lymphandectomy was not part of the pre-surgery plan but was required as one lymph node was larger than normal.

Immunohistochemistry using appropriate markers is essential in the correct diagnosis of glomus tumors. As seen in this case, neither imaging nor routine endoscopic biopsy was sufficient to rule out GIST. The appropriate immunology tests were required to make the diagnosis. Typically, GIST is positive for cKIT (CD117), carcinoid tumor is positive for chromogranin, and gastric lymphoma is positive for common leukocyte antigen, unlike glomus tumors, which are negative for all of these markers and characteristically positive for smooth muscle actin.(3,10-12 17) One misleading aspect of this case was that the biopsy yielded a positive result for cKIT (CD117), but subsequent immunohistochemical analysis yielded a negative result. Possible explanations include poor sensitivity and specificity of the test, that rare tumors are not expected among pathologists, and that the size of the biopsy was small and did not represent the entire tumor in the way a surgical specimen could.

Adverse histopathological prognostic factors for gastric glomus tumors include tumor size and lymphovascular invasion. Although rare, malignant gastric glomus tumors have been reported in the literature.3,10,18 Tumor size has been proposed as an indicator for malignancy 3,10, with sizes larger than 5 cm more likely to become malignant or metastasize. Vascular invasion is a second sign of poor prognosis.3 In this case, the tumor was 4 cm in size with lymphovascular invasion, but the Ki67 nuclear proliferation index was approximately 1% and the mitosis index was 1 in 50 with hematoxylin phloxine saffron staining, so its biological behaviour was likely not aggressive. Given this information, a favourable clinical outcome can be expected.

Also of interest is that the patient was infected with H. pylori, which has been shown to cause gastric symptoms and MALT. Therefore, it is reasonable to question whether H. pylori may be associated with gastric glomic tumors as well. A review of the literature 19-25 indicated that there were 6 patients with both gastric glomus tumor and H. pylori infection (including this case) and 21 patients with gastric glomus tumor without a diagnosed H. pylori infection. Most of these cases come from a single reference, and since H. pylori infection is common across the world, it is likely that there is no causal link, but more systematic studies could improve the data quality.

In conclusion, this case underscores the challenge of accurately diagnosing antral glomangioma before surgery. With current practices and technology, a definitive diagnosis will likely still require analysis of the surgical specimen. Nevertheless, this case suggests the importance of immunohistochemical testing for markers such as cKIT (CD117), chromogranin, common leukocyte antigen, and smooth muscle actin to facilitate a rapid and accurate differential diagnosis.