Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Industrial Data

versión impresa ISSN 1560-9146versión On-line ISSN 1810-9993

Ind. data vol.28 no.1 Lima ene./jun. 2025 Epub 15-Jul-2025

http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/idata.v28i1.28326

Design and Technology

Extraction of Calcium Citrate from Chicken Eggshells and Its Use as a Vitamin Supplement

1Master’s degree in Food Science and Technology. Currently working as a professor at Universidad Nacional de San Agustín (Arequipa, Peru). E-mail: npompilla@unsa.edu.pe

2PhD in Production Engineering. Currently working as a professor at Universidad Nacional de San Agustín (Arequipa, Lima). E-mail: mgonzalesi@unsa.edu.pe

3PhD in Environmental Sciences and Technologies. Currently working as a professor at Universidad Nacional de San Agustín (Arequipa, Lima). E-mail: ptanco@unsa.edu.pe

4Master’s degree in Food Science and Technology. Currently working as a professor at Universidad Nacional de San Agustín (Arequipa, Lima). E-mail: iacosta@unsa.edu.pe

Chicken eggshells are a common waste material in households and food industries. To make the most of them, we proposed extracting calcium citrate through a citric acid leaching process using lime juice as solvent. Our results indicated that the solute concentration increased in all treatments due to the consistent precipitation of calcium citrate. The highest yields were achieved with the most diluted solutions, with an optimal reaction time of six hours. The final product contained 20.83% calcium. We concluded that greater dilution of chicken eggshells in the citric acid from lime juice enables the extraction of a larger quantity of calcium in the form of citrate. Moreover, the calcium content in this compound is very close to that found in commercial supplements (21%), suggesting that it can be effectively used as a vitamin supplement.

Keywords: calcium; citric acid; leaching; calcium supplement

INTRODUCTION

Chicken eggshells have long been considered waste material, in both the food industry and households, typically disposed of with urban waste. However, they are sometimes repurposed in various ways: as adsorbent materials for wastewater, as pigments in the paint and paper industries, as additives in the food industry, as filler materials in the construction industry, or for extracting collagen from membranes. Although these applications help mitigate environmental impact, they remain insufficient.

According to the Ministry of Agricultural Development and Irrigation (MIDAGRI), Peru consumed 15.2 kg of eggs per capita in 2022, which is equivalent to 242 eggs per person. This implies that each Peruvian consumed roughly one egg daily for 67% of the year. National egg production during 2022 continued its upward trend, reaching 510 962 tons (Asociación Peruana de Avicultura [APA], 2023). This output resulted in roughly 58 249 tons of eggshells that were likely discarded into the environment, as they are often overlooked during culinary preparations and production processes such as making mayonnaise, breadmaking, and producing pasteurized dehydrated egg products, among others.

Given the substantial calcium content of eggshells, this research study aimed to develop new products. As a by-product of egg processing, eggshells could represent an option to address the nutritional needs of the population. By breaking down the original compounds in the eggshells to form new compounds, specifically calcium citrate, through a citric acid leaching process, it can offer health benefits and contribute to reducing solid waste.

This research aimed to extract calcium citrate from chicken eggshells for use as a vitamin supplement and food additive in the food industry. The general hypothesis proposes that chicken eggshells-often discarded with urban waste and rich in calcium carbonate in the form of calcite-can be utilized to extract calcium in the form of calcium citrate, ultimately contributing to human health.

Eggshells

Avian eggshells are calcareous, biomineralized structures, formed by calcium carbonate crystals within an organic matrix or protein network. They account for approximately 10% to 12.81% of the total weight of an egg (Nys et al., 2004; Yenice et al., 2016). The calcium carbonate (CaCO3) content of eggshells ranges from 93.6% to 95.0% (Fernández & Arias, 2000; Nys et al., 2004), while the average calcium content is between 35.5% and 44.3% (Park & Sohn, 2018; Rendon et al., 2003). Additionally, magnesium carbonate has an average content of 0.8%, and tricalcium phosphate averages 0.73% (Fernández & Arias, 2000). Eggshells also contain various elements, including P, K, Na, Ni, Mn, Co, Be, V, Sr, Zn, Fe, Cu, Cr, F, and Se (Park & Sohn, 2018; Schaafsma et al., 2000). They also contain very low levels of potential toxic elements such as Pb, Al, Cd, and Hg (Schaafsma et al., 2000). Furthermore, microbial contamination of eggshells is high and is characterized by the presence of aerobic, anaerobic, and coliform bacteria (Sharma et al., 2022), due to the microbiota originating from the cloaca, feathers, and cage-rearing systems.

The Importance of Calcium as a Mineral in the Human Body

Calcium is the most abundant mineral in the human body and is crucial for the formation and maintenance of bones and teeth, alongside phosphate and magnesium (Martínez de Victoria, 2016). About 99% of calcium in the body is found as hydroxyapatite in bone tissue. Calcium is essential for bone mineralization, growth, and maturation. It can exert its regulatory function passively or actively. The passive form occurs when plasma calcium levels regulate enzymatic reactions, while the active form involves the intracellular Ca2+ concentration (Martínez de Victoria, 2016). Additionally, calcium participates in metabolic processes and is absorbed in its ionic form (Ca2+). For this to happen, it must first be released from the complexes to which it is bound, through enzymatic action and the influence of pH. In the stomach, calcium complexes become soluble due to the acidic pH provided by hydrochloric acid. In the intestines, a rise in pH promotes the precipitation and absorption of calcium, primarily occurring in the duodenum and proximal jejunum, where the pH ranges from 3.5 to 6.7 (Farré & Frasquet, 1999).

Calcium Citrate as a Vitamin Supplement

Calcium citrate is the calcium salt of 2-hydroxy-1,2,3-propanetricarboxylic acid tetrahydrate. It appears as a crystalline, white, odorless powder that is soluble in water but insoluble in alcohol. According to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system and the Defined Daily Dose (DDD) established by the World Health Organization, calcium citrate is classified under ATC group A12 with the code A12AA09 (WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, 2024).

Calcium citrate offers several advantages, including superior absorption and bioavailability compared to other calcium salts. It can be taken with or without food without affecting its absorption, making it convenient for use at any time of day. Additionally, it is considered safe for individuals with a history of renal calculi (Zurita, 2002). Calcium citrate serves as a nutritional supplement and an oral source of calcium, helping to prevent and treat calcium insufficiencies in the human body while also contributing to the maintenance of healthy bones and teeth. It is soluble in gastric acid but becomes insoluble in the duodenum, resulting in only a fraction of calcium being available for absorption.

Calcium in food and supplements exists as elemental calcium and is often found in compound forms, mainly as carbonate, citrate, lactate, and phosphate. These compounds have varying degrees of absorption and bioavailability (Zurita, 2002); generally, the more soluble a calcium or magnesium salt is, the better its absorption and bioavailability.

The best way to obtain calcium is through dietary sources; however, a significant percentage of the population does not consume the recommended intake of calcium, magnesium, vitamin D (Olza et al., 2017), and phosphorus (Martínez de Victoria, 2016). This deficiency is often due to inadequate intake of these nutrients in the daily diet, highlighting the need for dietary supplements. The required dosage of supplements depends on the amount of calcium obtained from food. Calcium supplements are best absorbed when ingested with food and in small doses (500 mg or less) multiple times a day.

There are many calcium compounds on the market, with elemental calcium content ranging from 9% to 40% and different routes of administration depending on their formulation. For instance, carbonate-based supplements contain 40% calcium, citrates contain 21%, gluconates contain 9%, lactates contain 13%, and bone meal, oyster shells, and dolomites contain 30% (Zurita, 2002). Calcium and magnesium salts or complexes are also used as nutritional supplements (Rodríguez et al., 2014) and should be considered in dietary planning.

Calcium plays a vital role in the human body. It not only strengthens bones but also helps muscles, the heart, and nerves function properly. If dietary calcium intake is insufficient, the body will draw calcium from the bones. Over time, this process weakens the bones and increases the risk of developing osteoporosis, a disease that causes the bones to become weak and brittle. People with osteoporosis are more prone to bone fractures. Scientific evidence supports the use of calcium and vitamin D supplements in patients with osteoporosis and vitamin D deficiency, recommending daily doses of 2000 international units (IU) or 0.05 mg of vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol). Any medication prescribed to treat osteoporosis should be accompanied by a calcium and vitamin D3 supplement (Sosa & Gómez, 2021).

In the pursuit of raw materials with greater bioavailability of calcium, Rodríguez et al. (2014) extracted calcium magnesium citrate salt from dolomite deposits, a mineral composed of double calcium and magnesium carbonate [CaMg(CO3)2], using citric acid solutions as the extraction medium. Similarly, Vásquez and Glorio (2007) obtained calcium magnesium citrate from mussel shells (Aulacomya ater [Molina]), composed of calcareous material, using hydrochloric acid solutions as a leaching agent. Their research focused on obtaining calcium and magnesium citrate for use in the production of products such as peach nectar. In an effort to improve processes or propose alternative methods, Rosas et al. (2018) used ground eggshells as a source of calcium in the production of fettuccine-type pasta to create calcium-rich foods. Similarly, Pérez et al. (2018) incorporated eggshell micropowders into the production of a functional, fortified yogurt, directly adding them to food preparations.

METHODOLOGY

The study started by providing context on the information about the characteristics and composition of chicken eggshells, the citric acid leaching method, and the citrate-based vitamin supplements. Experiments were then conducted according to the specified number of treatments outlined in the experimental design. The results were discussed, and finally, the conclusions of the research were drawn.

Materials

Chicken eggshells were sourced from waste material collected at the bakery unit of the Chemical Engineering Program at Universidad Nacional de San Agustín, where chicken eggs are used for daily production. Lime juice was obtained from “common or acid lime” of the Key lime variety (Citrus aurantifolia Swingle), purchased at a local market. The chemical inputs used for physicochemical and mineral content analysis were acquired from local laboratories. The experimentation, physicochemical analysis, mineral analysis, and microbiological analysis were conducted in the inorganic chemistry and industrial bioprocess laboratories of the Chemical Engineering Program at the same university. The methodology employed in the research consisted of two stages: the first involved the pretreatment of chicken eggshells, and the second focused on obtaining calcium citrate.

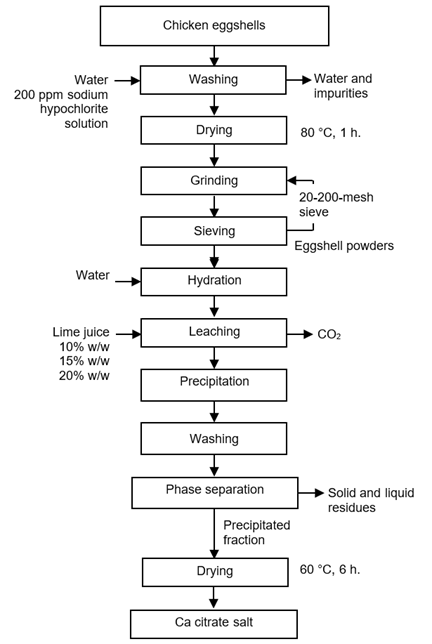

Pretreatment of chicken eggshells

The pretreatment process involved washing the eggshells and reducing their particle size (Figure 1) to increase the contact area for better calcium citrate extraction. The proportion of dirty eggshells was significant, and there was no evidence of proper washing of the eggs before use. Once collected, the eggshells were washed with water to remove impurities, a quick process since the impurities were only lightly adhered to the shells. They were then disinfected by immersion in a 200-ppm sodium hypochlorite solution for 20 minutes, followed by a second wash to remove any sodium hypochlorite residues.

The eggshells were then placed in a laboratory oven at 80 °C for 15 minutes and subsequently ground. Due to their large size and fragile structure, a disk mill was used for pre-grinding. An electric grain grinder (stainless steel Nima, 300 W) was employed to achieve a fine grind. Finally, the ground eggshells were passed through a series of sieves (W.S. Tyler Ro-Tap RX-29 Sieve Shaker) conforming to the US Standard ASTM E-11, featuring mesh openings specified in micrometers (µm), to obtain the desired particle size distribution and proportions.

Extracting Calcium Citrate by Citric Acid Leaching

This process involved extracting calcium citrate from eggshells using citric acid from lime juice, as illustrated in Figure 1. Before the extraction, water was added to the ground eggshells in a ratio of 50% of the weight of the solute. This step was intended to hydrate the ground eggshells and increase the reaction speed. The beaker containing the hydrated, ground eggshells was placed on a magnetic stirrer, and lime juice was gradually added in increments while stirring. This was done to prevent overflow due to the effervescence caused by gas release. The proportions of ground eggshells and lime juice used were 10%, 15%, and 20% (w/w), with reaction times of 2, 4, and 6 hours.

After the extraction process, three distinct phases were observed, which were separated physically by sieving and filtration. The precipitated fraction was washed with distilled water and then dried in a laboratory oven at 60 °C for 6 hours. Subsequently, it was finely ground and passed through a 140-mesh sieve. Various treatments were applied to examine particle size distribution, solute proportions, and reaction time to determine the optimal parameters for extracting calcium citrate.

For the characterization of both the eggshells and calcium citrate, the chemical composition was analyzed using several methods. Moisture content was assessed according to the Peruvian technical standard (NTP 209.008), organic matter was measured using the Walkley-Black method, calcium was determined via spectrophotometry, phosphorus was analyzed using the colorimetric method, magnesium was quantified using the complexometric method, and carbonates were evaluated using the gas-volumetric method. Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) was utilized to determine the total metal content.

Microbiological Analysis

The extracted calcium citrate appears as a powdery precipitate, and the solvent used is an organic compound; both are highly susceptible to contamination. To assess its safety, a total count of fungi and yeasts was conducted by inoculating samples onto oxytetracycline gentamicin agar. Additionally, bacteria and mesophilic aerobes were quantified using agar plate count medium in a sterile plate inoculation (International Commission on Microbiological Specifications for Foods [ICMSF], 2011).

Sensory Testing

To ensure the degree of acceptability of calcium citrate as a vitamin supplement, we conducted a differentiated organoleptic assessment using a randomized block experimental design with ten samples of calcium citrate powder. The acceptability test utilized the hedonic scale method, involving a panel of ten untrained adults who regularly consume calcium supplements. Participants rated their level of liking on a scale from one to five, defined as follows: (1) “I dislike it very much”, (2) “I dislike it moderately”, (3) “I neither like nor dislike it”, (4) “I like it moderately”, and (5) “I like it very much”. This evaluation focused on the attributes of odor, color, flavor, and texture to identify the product with the best attributes.

RESULTS

Chemical Composition of Eggshells

The results obtained from the chemical composition analysis of the eggshell sample are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Chemical Composition of Chicken Eggshells.

| Component | Content (%) |

|---|---|

| Calcium carbonate - CaCO3 | 88.93 |

| Magnesium carbonate - MgCO3 | 0.85 |

| Calcium phosphate - Ca3 (PO4) 2 | 1.81 |

| Organic matter | 5.81 |

| Moisture | 2.60 |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Particle Size Distribution of Chicken Eggshell Powder

The eggshells were finely ground, producing powders with particle sizes ranging from 20 to 200 mesh sieve (US standard sieve sizes), expressed as material retained, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Particle Size Distribution of Chicken Eggshell Powders.

| Sieve | Retained | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| US STD | Opening (µm) | (g) | (%) |

| 20 | 850 | 17.91 | 1.79 |

| 30 | 595 | 277.78 | 27.78 |

| 40 | 425 | 327.64 | 32.76 |

| 60 | 250 | 134.47 | 13.45 |

| 100 | 150 | 46.95 | 4.70 |

| 140 | 106 | 36.73 | 3.67 |

| 200 | 75 | 113.01 | 11.30 |

| Pan | 45.51 | 4.55 | |

| Total | 1000.00 | 100.00 | |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Calcium Citrate Production Yield

The yield or amount of the calcium citrate obtained was evaluated based on three factors: particle size distribution, solute proportion (ground eggshells), and reaction time. It is important to note that the average citric acid content in the limes was 5%. During the experiment, different weight-to-weight percentages (% w/w) were used to optimize the yields.

To assess the yield based on particle size distribution, seven treatments (M) were conducted to extract calcium citrate from ground eggshells using mesh sieve sizes 20, 30, 40, 60, 100, 140, and 200, as shown in Table 3. The initial proportion of ground eggshells to lime juice was set at 20% w/w, and the reaction time was 4 hours.

Table 3 Proportions of Solute After the Chemical Reaction.

| Treatment | US STD Sieve | Final Solute Proportion (% w/w) | Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 20 | 23.88 | 3.88 |

| M2 | 30 | 23.86 | 3.86 |

| M3 | 40 | 23.78 | 3.78 |

| M4 | 60 | 23.76 | 3.76 |

| M5 | 100 | 23.68 | 3.68 |

| M6 | 140 | 23.46 | 3.46 |

| M7 | 200 | 23.44 | 3.44 |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

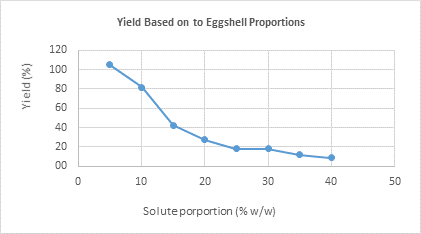

The yield behavior of calcium citrate obtained through the leaching process at various mesh sieve sizes is presented in Figure 2.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Figure 2 Yield based on ground eggshell particle size distribution.

To assess the yield based on solute proportions, eight treatments (S) were conducted using different proportions of ground eggshells in lime juice, with a sieve mesh size of 30 and a treatment duration of 4 hours, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4 Comparison Between Initial and Final Solute Proportions.

| Treatment | Solute proportion (% w/w) | Amount (g) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Final | Product | Solid Residue | Membrane | |

| S1 | 5 | 8.56 | 5.24 | 1.90 | 1.42 |

| S2 | 10 | 14.78 | 8.14 | 5.22 | 1.42 |

| S3 | 15 | 19.22 | 6.34 | 11.02 | 1.86 |

| S4 | 20 | 24.32 | 5.54 | 17.42 | 1.36 |

| S5 | 25 | 28.38 | 4.50 | 22.52 | 1.36 |

| S6 | 30 | 34.74 | 5.44 | 28.26 | 1.04 |

| S7 | 35 | 38.50 | 4.14 | 33.28 | 1.08 |

| S8 | 40 | 42.94 | 3.58 | 38.30 | 1.06 |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

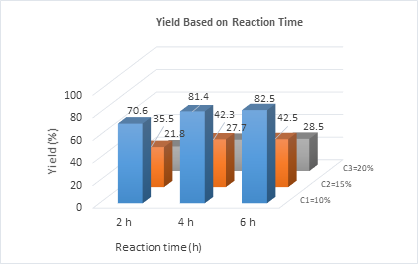

The best yields were obtained in solutions with lower solute proportions, specifically at 5%, 10%, and 15% w/w. Figure 3 displays an inflection point beginning at 20% ground eggshell content, where the yield starts to decline.

Lastly, to assess yield based on chemical reaction time and solute proportions, nine treatments (T) were conducted using ground eggshell proportions of 10%, 15%, and 20% w/w, and reaction times of 2, 4, and 6 hours, as shown in Figure 4.

Calcium Content in the Final Product

After obtaining calcium citrate, the calcium content of the various treatments was assessed using a fluorescence spectrophotometer. The results revealed variations in calcium concentration across all treatments. These variations are detailed in Table 5, which presents data for solute proportions of 10%, 15%, and 20%, along with reaction times of 2, 4, and 6 hours.

Table 5 Yield Based on Ground Eggshells Proportion.

| Treatment | Solute Proportion (% w/w) | Reaction Time (h) | Calcium Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 10 | 2 | 20.65 |

| T2 | 10 | 4 | 20.80 |

| T3 | 10 | 6 | 20.83 |

| T4 | 15 | 2 | 20.02 |

| T5 | 15 | 4 | 20.36 |

| T6 | 15 | 6 | 20.38 |

| T7 | 20 | 2 | 19.42 |

| T8 | 20 | 4 | 19.68 |

| T9 | 20 | 6 | 19.72 |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

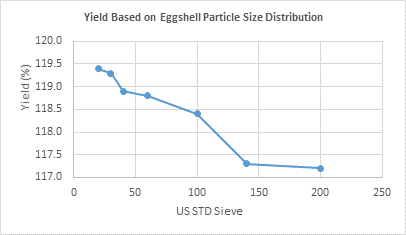

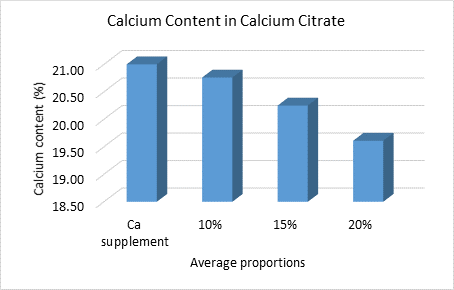

The average calcium content for the tested proportions of 10%, 15%, and 20% w/w was measured at 20.76%, 20.25%, and 19.61%, respectively (Figure 5). For comparison, the calcium content in commercial citrate complex supplements is 21%.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Figure 5 Calcium content in average proportions of eggshells and calcium supplements.

Mineral Content in Eggshell, Final Product, and Residues

The metal content presented in Table 6 corresponds to the chicken eggshells used in the experiment, the dry-basis product obtained from treatment T3, and the resulting solid and liquid residues. This content was determined through metal analysis using ICP-MS.

Table 6 Mineral Content in Eggshells, Final Product, and Residues in Parts Per Million (ppm).

| Mineral | Eggshells | Final product (T3) | Residue | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Reference* | Liquid | Solid | ||

| Calcium (Ca) | 355 700.0 | 443 450.00 | 208 300.0 | 21 700.0 | 24 670.0 |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 4 500.0 | 3 468.20 | 1 036.0 | 14 700.0 | 3 542.0 |

| Sodium (Na) | 2 700.0 | 467.76 | 2 173.0 | 8 726.0 | 1 830.0 |

| Potassium (K) | 3 700.0 | 403.93 | 3 803.0 | 125 700.0 | 6 732.0 |

| Phosphorus (P) | 1 000.0 | 1 093.40 | 353.8 | 7 667.0 | 753.5 |

| Iron (Fe) | 51.7 | - | 32.4 | 51.9 | 45.9 |

| Strontium (Sr) | 26.0 | - | 34.7 | 6.4 | 22.9 |

| Boron (B) | 20.8 | - | 13.8 | 41.5 | 19.6 |

| Barium (Ba) | 43.7 | - | 9.9 | 16.5 | 37.7 |

| Manganese (Mn) | 7.5 | 0.06 | 7.2 | - | 7.7 |

| Aluminum (Al) | 21.1 | - | 8.4 | 23.0 | 17.1 |

| Tin (Sn) | 62.4 | - | 5.1 | 103.0 | 5.4 |

| Copper (Cu) | 4.8 | - | 3.2 | 12.8 | 3.9 |

| Zinc (Zn) | 8.2 | - | 3.2 | 46.1 | 10.0 |

| Chromium (Cr) | 1.7 | - | 1.0 | 5.8 | 1.5 |

| Selenium (Se) | 1.6 | - | 1.2 | 31.6 | 0.8 |

| Nickel (Ni) | 0.9 | 0.15 | 1.0 | 2.3 | 0.9 |

| Silicon (Si) | 2.2 | - | 0.1 | 95.3 | 2.7 |

| Vanadium (V) | 1.1 | 0.38 | 1.4 | - | 0.9 |

| Lithium (Li) | 1.0 | - | 0.2 | 3.2 | 0.7 |

| Cobalt (Co) | 0.4 | 0.19 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| Silver (Ag) | - | - | 0.6 | 5.7 | - |

| Bismuth (Bi) | 0.4 | - | - | 0.7 | - |

| Molybdenum (Mo) | 0.4 | - | - | - | 0.4 |

| Lead (Pb) | 1.2 | - | - | 7.5 | 0.6 |

| Beryllium (Be) | - | 0.03 | - | - | - |

Note: (-) Values below detection limits. (*) The Influence of Hen Aging on Eggshell Ultrastructure and Shell Mineral Components (Park & Sohn, 2018).

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Microbiological Analysis of the Obtained Calcium Citrate

The microbiological analysis of the final product (calcium citrate) was conducted to evaluate several parameters. These included the counts of mold (fungi), yeasts, aerobic bacteria (mesophiles), and the presence of Salmonella. In all cases, the microbial counts measured in colony-forming units (CFU) were below the detection limits as specified in the standard, i.e., <10 CFU/g. Notably, Salmonella was completely absent.

Sensory Testing of the Obtained Calcium Citrate

After obtaining numerical scores for each attribute from the panelists, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied. To assess the degree of acceptance among the panelists, the mean and standard deviation were calculated. The best results were obtained for texture attributes, followed by flavor, color, and odor, as indicated in Table 7. To determine differences between the treatments, the F statistic was calculated, yielding an F value of 0.414 for all attributes, which was lower than the critical F value of 3.354.

Table 7 Results of the ANOVA for Each Evaluated Attribute.

| Attribute | Sum of Squares | Degrees of Freedom | Mean Squares | F | Probability | Critical F Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odor | 0.267 | 2 | 0.133 | 0.414 | 0.665 | 3.354 |

| Color | 0.245 | 2 | 0.133 | 0.414 | 0.665 | 3.354 |

| Taste | 0.222 | 2 | 0.133 | 0.414 | 0.665 | 3.354 |

| Texture | 0.224 | 2 | 0.133 | 0.414 | 0.665 | 3.354 |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Statistical Analysis

ANOVA variance analysis was also conducted (Table 8) for the alternative hypothesis (H1) to analyze whether a statistically significant difference exists among the measurements of nine treatments (T1 to T9), with two repetitions each. The analysis yielded a mean of 48.017 and a standard deviation of 23.278, with a significance level of 0.05. The calculated F values (41.711) were greater than the critical F values (4.256).

Table 8 Results of the ANOVA for Yield in the Nine Treatments.

| Origin of variations | Sum of squares | Degrees of freedom | Mean squares | F | Probability | Critical F Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | 284.29 | 2 | 142.145 | 41.711 | 1.34E-09 | 4.256 |

| Columns | 8896.46 | 2 | 4448.232 | 13040.418 | 2.63E-16 | 4.256 |

| Interaction | 27.56 | 4 | 6.889 | 20.196 | 1.61E-04 | 3.633 |

| Within the group | 3.07 | 9 | 0.341 | |||

| Total | 9211.38 | 17 |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Additionally, SPSS version 27 was used to conduct the Tukey test for comparisons between treatments and groups. The group means within the homogeneous subsets were obtained, as shown in Table 9, with an error term (mean square error) of 0.356, a harmonic mean sample size of 6, and a significance level (α) of 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Chemical Composition of Eggshells

The chemical analysis of the eggshells revealed that calcium carbonate constitutes 88.93% of the material, making it the most predominant component. This finding confirms that chicken eggshells are a significant source of calcium. However, this percentage differs from previous studies; for instance, Nys et al. (2004) reported a composition of 95%, while Neunzehn et al. (2015) found it to be 93.6%. The discrepancies of 6.07% and 4.67%, respectively, can be attributed to the various types of chicken eggshells used in this study, which included shells with different characteristics such as pigmentation, thickness, and the rearing systems of the chickens, especially since discarded material was used.

In addition to calcium carbonate, magnesium carbonate was found in a proportion of 0.85%, and tricalcium phosphate was present in a proportion of 1.81%. The magnesium carbonate content was higher than that reported by Fernández and Arias (2000) and Pérez et al. (2018), while the tricalcium phosphate content was slightly higher as well. The organic matter content was measured at 5.81%, and the moisture content was 2.6%. Both values are slightly higher than those reported, likely due to the mixture of chicken eggshells used.

Particle Size Distribution of Chicken Eggshell Powders

Particle size distribution was determinant in the extraction of calcium citrate due to the varying structure of the eggshells. Some areas of the shells are quite strong and compact, while others are somewhat weak; eggshell structure changes or degrades as the hen ages (Park & Sohn, 2018). The highest amount of retained material was observed in the 40-mesh sieve, accounting for 32.76%, followed by the 30-mesh sieve with 27.78%. The differences in the particle size distribution observed by Pérez et al. (2018) may be attributed to variations in grinding time, the equipment used, and, most importantly, the specific research purposes, rather than the structural characteristics of chicken eggshells.

Calcium Citrate Production Yield

The fineness of the eggshell powders, particularly those passing through the 100, 140, and 200-mesh sieves, resulted in difficulty distinguishing them from non-reacting solid residue, complicating the separation process. Consequently, the production yield was assessed based on the proportion of solids formed after the chemical reaction, resulting in final solute proportions exceeding 20% w/w in all cases.

There was a slight difference in the formation of the solute at the end of the reaction. Sieves 20 and 30 yielded the highest production, while sieves 100, 140, and 200 obtained lower yields (Figure 2). This variation is likely due to the reduced reaction surface area, as the material is highly pulverized, preventing the free migration of atoms and leading to oversaturation in the solution. Therefore, particle size is crucial, and it is important to identify the optimal size to prevent oversaturation and facilitate the progress of the chemical reaction.

Based on the solute proportions, the best results were achieved with lower solute concentrations of 5%, 10%, and 15% w/w, while minimal differences were noted at 20% w/w. However, using lower proportions leads to increased costs for lime juice, highlighting the reduced cost-efficiency of calcium citrate at low proportions. Proportions of 10%, 15%, and 20% w/w are deemed optimal. Additionally, a significant amount of membrane was also observed, as the eggshells were used in their entirety without removing the membranes, which accounts for approximately 3%-3.5% of the eggshells’ total weight.

Based on the reaction time and proportions of solute, the best results for the calcium citrate were achieved in treatments T2 and T3, with yields of 81.4% and 82.5% after 4 and 6 hours of reaction, respectively. Beyond this time, production increased only slightly, leading to the conclusion that 6 hours is the optimal reaction time in treatment T3. Extended reaction periods pose a risk of contamination due to the presence of organic matter.

Calcium Content in the Final Product

The initial calcium content in the eggshells was 35.57%. From this, the yields obtained from treatments T1, T2, and T3 were 58.05%, 58.48%, and 58.56%, respectively. Yields for treatments T4, T5, and T6 were 56.28%, 57.24% and 57.30%, respectively, while treatments T7, T8 and T9 achieved yields of 54.60%, 55.33% and 55.44%. Treatment T3 delivered the highest yield; however, treatment T2 exhibited minimal variation and a shorter reaction time. Both treatments are considered optimal, as they reduce the risk of contamination caused by prolonged reaction times. Thus, the optimal reaction time is between 4 and 6 hours.

The average calcium content obtained in the 10%, 15%, and 20% w/w proportions was 20.76%, 20.25%, and 19.61%, respectively. This suggests a slight difference among the treatments studied (Figure 5), with the highest calcium content found in the 10% w/w proportion. When comparing these results to commercial calcium citrate supplements, which have a calcium content of 21%, the differences are not substantial, especially for treatments corresponding to the 10% w/w proportion. Specifically, Treatments T1 (20.65%), T2 (20.80%), and T3 (20.83%) show differences of 1.66%, 0.95%, and 0.81%, respectively, compared to the commercial supplements. This implies that a 5 g sample of calcium citrate, the recommended daily intake for an adult, contains 1032.5 mg of calcium in T1, 1040.0 mg in T2, and 1041.5 mg in T3. These amounts are within the recommended daily limits of 700, 1000, or 1200 mg, depending on the stage of life (Instituto Nacional de Artritis y Enfermedades Musculoesqueléticas y de la Piel [NIAMS], 2023).

Upon comparing the calcium (20.83%) and magnesium (1.036%) content of the calcium citrate with the findings reported by Vásquez and Glorio (2007), only minimal differences were observed. Their study reported elemental calcium content of 20.5% and magnesium content of 0.0927% in calcium and magnesium citrate derived from mussel shells (Aulacomya ater Molina). However, significant differences are observed when compared to the results obtained by Rodríguez et al. (2014), who reported calcium content of 10.47% and magnesium content of 4.67% in calcium and magnesium citrate. This difference arises from the raw materials used. Eggshells, primarily composed of calcite, contain approximately 88.93% calcium carbonate and 0.85% magnesium carbonate. In contrast, dolomite, a double carbonate of calcium and magnesium [CaMg(CO3)2], contains 30.41% calcium oxide (CaO) and 21.86% magnesium oxide (MgO), along with other compounds. This variation influences the final calcium content in the products.

Furthermore, upon comparing the calcium content (20.83%) of the calcium citrate with the results reported by Rosas et al. (2018), who found an average calcium content of 9.06% in fettuccine-type pasta enriched with eggshells, an approximate 50% difference in calcium content was observed. Meanwhile, Pérez et al. (2018) reported a calcium content of 0.232% (232 mg/100g) in fortified functional yogurt, which is significantly lower than the calcium content found in this study. These discrepancies in calcium content may stem from the direct addition of powdered eggshells without prior treatment, as occurs in the extraction of calcium citrate, which constitutes the basis for citrate-based calcium supplements.

Mineral Content in Eggshell, Final Product and Residues

In addition to calcium (Ca) and magnesium (Mg), sodium (Na), potassium (K), and phosphorus (P) are found in slightly lower amounts than those in eggshells, closely resembling the results obtained by Vásquez and Glorio (2007). It is noteworthy that the Ca2+ content decreases with the age of the hen, while the levels of Na+ and K+ tend to increase (Park & Sohn, 2018). Several metals, including Fe, Sr, B, Ba, Mn, Al, Sn, Cu, and Zn, were detected in lower quantities compared to the contents reported by Rodríguez et al. (2014), who documented the presence of SiO2, Al2O3, and Fe2O3. Additionally, Cr, Se, Ni, Si, Si, V, Li, Co, and Ag were detected in very small amounts, consistent with the findings in eggshell studies conducted by Park and Sohn (2018). Notably, As, Be, Cd, Hg, Ti, and Tl were not detected in the final product, eggshells, or any residues. This contrasts with the findings of Rodríguez et al. (2014), who reported the presence of Cd, Pb, Hg, and As. Lastly, Bi, Mo, and Pb contents were detected in eggshells, as noted by Milbradt et al. (2015), who did not detect Cd or Pb in their eggshell samples’ analyses. Similarly, Dos Santos et al. (2010) reported no detection of Cd, Pb, or Hg.

Eggshells offer distinct advantages over other calcium sources due to the absence of elements harmful to human health. This waste material holds potential for diverse industrial applications and broader benefits for mankind. A reduction in the concentration of all elements was observed in both solid and liquid residues compared to their initial content in the eggshells; however, the values obtained may vary depending on the specific material and proportions used. Overall, the concentrations of magnesium, sodium, potassium, and phosphorus are minimal, suggesting that a slight increase in intake would remain within permissible limits. Furthermore, the concentrations of nickel, molybdenum, aluminum, boron, arsenic, and cadmium are well below the established allowable thresholds.

Microbiological Analysis of the Obtained Calcium Citrate

The microbiological analysis conducted on the obtained calcium citrate revealed that all samples had microbial counts below the detection limit of 10 CFU/g. Furthermore, the complete absence of Salmonella indicates that the calcium citrate produced is safe for human consumption and suitable for use in food products.

Sensory Testing of the Obtained Calcium Citrate

The sensory analysis conducted with panelists evaluated the texture, taste, color, and odor attributes of the calcium citrate. The results showed no statistically significant differences at a 95% confidence level in treatment T3, which exhibited the best yields. This suggests that the product obtained is pleasant to the palate.

Statistical Analysis

The ANOVA analysis indicated p-values below 0.05, and the calculated F-statistic value (41.711) exceeded the critical F-value (4.256). Therefore, the alternative hypothesis (H1) is accepted, demonstrating a statistically significant difference in the yield of the final product. Based on the Tukey test, homogeneous subsets’ means were determined (Table 9), with an error term represented by a mean square error of 0.356, a harmonic mean sample size of 6, and a significance level (α) of 0.05. The greatest difference was observed between treatments T3 and T7, with T3 achieving the highest yield of 82.5%. This treatment, which used a concentration of 10% eggshells in lime juice and a reaction time of 6 hours, resulted in a final product containing 20.83% calcium, representing a yield of 58.56% based on the calcium content of the eggshells.

CONCLUSIONS

Chicken eggshells contain 88.93% calcium carbonate, confirming their status as a natural substance and an important source of this mineral. The remaining 11.07% consists of magnesium carbonate, calcium phosphate, organic matter, and moisture. When eggshells were subjected to a leaching process using citric acid from lime juice, calcium citrate was obtained with a yield of 82.5% in treatment T3. The final product contained 83% calcium, corresponding to a yield of 58.56% of the initial calcium content, based on a 10% w/w solution of eggshells and lime juice. Treatment T3 proved to be the most effective for obtaining calcium citrate. Therefore, a lower proportion of eggshells in lime juice results in greater calcium extraction in the form of citrate. Conversely, a higher concentration of eggshells leads to more calcium being extracted as this compound.

Additionally, there is a significant interaction between the content of eggshells and the concentration of citric acid in lime juice, which notably influences the extraction outcomes at different concentrations.

The choice of raw materials and extraction methods also affects the calcium content of the final product, whether in the form of calcium citrate or processed food products. Furthermore, the solid and liquid residues from the process still contain minerals that can be repurposed for producing balanced animal feed, fertilizers, or other products. This process also helps reduce pollution levels caused by waste from the food industry and households, effectively giving waste a new use.

Lastly, due to the socio-economic limitations, access to state-of-the-art equipment and measuring instruments was limited. Nevertheless, implementing such resources and collaborating with specialists in the field could be beneficial.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Universidad Nacional de San Agustín for its support in presenting and sharing this research. They also wish to thank Ph.D. Hugo Jacinto Lastarria Tapia for his unwavering support throughout the development of this research project.

REFERENCES

Asociación Peruana de Avicultura. (2023). Boletín APA Informa. (Edición 011 noviembre 2023). https://apa.org.pe/portfolio-item/boletin-noviembre-2023/ [ Links ]

Dos Santos Vilar, J., Oliveira Sabaa-Srur, A., y Garcia Marques, R. (2010). Composição química da casca de ovo de galinha em pó. Boletim do Centro de Pesquisa de Processamento de Alimentos, 28(2), 247-254. http://dx.doi.org/10.5380/cep.v28i2.20439 [ Links ]

Farré Rovira, R., y Frasquet Pons, I. (1999). Calcio, fósforo y magnesio. En M. Hernández Rodríguez, y A. Sastre Gallego (Eds.), Tratado de Nutrición (pp. 217-228). Madrid, España: Ediciones Díaz de Santos. S.A. [ Links ]

Fernández, M. S., y Arias, J. L. (2000). La cáscara de huevo: Un modelo de biomineralizacion, Monografías de Medicina Veterinaria, 20(2). https://monografiasveterinaria.uchile.cl/index.php/MMV/article/view/5017 [ Links ]

International Commission on Microbiological Specifications for Foods (ICMSF). (2011). Microorganisms in Foods 8: Use of Data for Assessing Process Control and Product Acceptance. Springer Nature Switzerland AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-9374-8 [ Links ]

Martínez de Victoria, E. (2016). El calcio, esencial para la salud. Nutrición Hospitalaria,33(4), 26-31. https://dx.doi.org/10.20960/nh.341 [ Links ]

Milbradt, B. G., Müller, A. L. H., da Silva, J. S., Lunardi, J. R., Milani, L. I. G., de Moraes Flores, E. M., Kolisnki Callegaro, M., y Emanuelli, T. (2015). Casca de ovo como fonte de cálcio para humanos: composição mineral e análise microbiológica. Ciência Rural, 45(3), 560-566. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-8478cr20140532 [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Artritis y Enfermedades Musculoesqueléticas y de la Piel. (2023). El calcio y la vitamina D: importantes para la salud de los huesos. https://www.niams.nih.gov/es/informacion-de-salud/el-calcio-y-la-vitamina-D-importantes-para-la-salud-de-los-huesos [ Links ]

Neunzehn, J., Szuwart, T., y Wiesmann, H. P. (2015). Eggshells as natural calcium carbonate source in combination with hyaluronan as beneficial additives for bone graft materials, an in vitro study. Head & Face & Medicine, 11(12). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13005-015-0070-0 [ Links ]

WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. (2024). ATC/DDA Index 2024. https://atcddd.fhi.no/filearchive/documents/1_atc_ddd_new_and_alterations_2024_final.xlsx [ Links ]

Nys, Y., Gautron, J., Garcia-Ruiz, J. M., y Hincke, M. T. (2004). Avian Eggshell Mineralization: Biochemical and Functional Characterization of Matrix Proteins. Comptes Rendus Palevol, 3(6-7), 549-562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crpv.2004.08.002 [ Links ]

Olza, J., Aranceta-Bartrina, J., González-Gross, M., Ortega, R. M., Serra-Majem, L., Varela-Moreiras, G., y Gil, Á. (2017). Reported Dietary Intake, Disparity between the Reported Consumption and the Level Needed for Adequacy and Food Sources of Calcium, Phosphorus, Magnesium and Vitamin D in the Spanish Population: Findings from the ANIBES Study, Nutrientes, 9(2), 168. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/nu9020168 [ Links ]

Park J. A., y Sohn, S. H. (2018). The Influence of Hen Aging on Eggshell Ultrastructure and Shell Mineral Components.Korean Journal for Food Science of Animal Resources,38(5), 1080-1091. https://doi.org/10.5851/kosfa.2018.e41 [ Links ]

Pérez, G., Guzmán, J., Duran, K., Ramos J., y Acha, V. (2018). Aprovechamiento de las cascaras de huevo en la fortificación de alimentos.Revista Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación,16(18), 29-38. http://www.scielo.org.bo/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2225-87872018000200003 [ Links ]

Rendón, U., Carrillo, S., Arellano, L. G., Casas, M. M, Pérez, F., y Avila, E. (2003). Composición química del residuo de la extracción de alginatos (Macrocystis pyrifera). Su aprovechamiento en la alimentación de gallinas ponedoras. Revista Cubana de Ciencia Agrícola, 37(3), 291-297. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/1930/193018048011.pdf [ Links ]

Rodríguez Chanfrau, J. E., Martínez Álvarez, L., y Bermello Crespo, A. (2014). Evaluation of calcium and magnesium citrate from Cuban dolomite.Revista Cubana de Farmacia, 48(4), 636-645. https://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/far/v48n4/far12414.pdf [ Links ]

Rosas, R., Gómez, N. O., Tomás, E., Hernández, A., Dorantes, J. D., García, B., y Vázquez-Rodríguez, G. A. (2018). Valorización de cáscaras de huevo como suplemento de calcio en pasta tipo fettuccine. Pädi: Boletín Científico de Ciencias Básicas e Ingenierías del ICBI, 5(10), 4-6. https://doi.org/10.29057/icbi.v5i10.2878 [ Links ]

Schaafsma, A., Pakan, I., Hofstede, G. J., Muskiet, F. A., Van Der Veer, E., y Vries, P. J. (2000). Mineral, amino acid, and hormonal composition of chicken eggshell powder and the evaluation of its use in human nutrition. Poultry science, 79(12), 1833-1838. https://doi.org/10.1093/ps/79.12.1833 [ Links ]

Sharma, M. K., McDaniel, C. D., Kiess, A. S., Loar, R. E., y Adhikari, P. (2022). Effect of housing environment and hen strain on egg production and egg quality as well as cloacal and eggshell microbiology in laying hens. Poultry Science, 101(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2021.101595 [ Links ]

Sosa Henríquez, M., y Gómez de Tejada Romero, M. J. (2021). La suplementación de calcio y vitamina D en el manejo de la osteoporosis. ¿Cuál es la dosis aconsejable de vitamina D? Revista de Osteoporosis y Metabolismo Mineral, 13(2), 77-83. https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/s1889-836x2021000200006 [ Links ]

Vásquez, W. y Glorio, G. (2007). Obtención de calcio y magnesio a partir de conchas de choro (Aulacomya ater Molina) para enriquecer un néctar de durazno (Prunus persica L.) variedad blanquillo. Revista de la Sociedad Química del Perú, 73(4), 235-248. [ Links ]

Yenice, G., Kaynar, O., Ileriturk, M., Hira, F., y Hayirli, A. (2016). Quality of Eggs in Different Production Systems.Czech J. Food Sci.,34(4), 370-376. https://doi.org/10.17221/33/2016-CJFS [ Links ]

Zurita, L. (2002). Utilización racional del calcio en osteoporosis. https://artritisylupus.com/utilizacion-racional-del-calcio-en-osteoporosis/ [ Links ]

Authors’ Contribution

Nidia Pompilla Cáceres (main author): Investigation, conceptualization, and formal analysis.

Marleni Gonzáles Iquira (coauthor): Investigation, methodology, writing, and (review & editing).

Paul Tanco Fernández (co-author): Investigation, writing (original draft), and validation.

Irina Acosta Gonzáles (co-author): Investigation, methodology, and data curation.

Received: June 20, 2024; Accepted: September 11, 2024; pub: July 15, 2025

texto en

texto en