1. Introduction

The climate crisis is aggravated by an extractivist economic system and unsustainable production and consumption patterns that endanger the sustenance of all the planet’s life forms (Sánchez De Jaegher, 2018). To solve this problem, the sustainable development paradigm has attempted to encourage the modification of this concerning planetary trajectory (Jeronen, 2013). Nonetheless, some of the Sustainable Development (SD) paradigm’s underlying values could limit its implementation and continue to fuel an unsustainable trajectory, undermining some of its goals (Vasseur and Baker, 2022).

This is because the SD paradigm -as is the extractivist economy are linked to ideological legacies that have been reinforced since colonial times. These legacies can encourage mindsets that contribute to the clima-te crisis. This is because both SD and the extractivist economic logic reflect a legacy of colonization though worldview rooted in Western values that have become the prevailing civilizational paradigm and worldview (Grosfoguel, 2008; Quijano, 2019).

The values of the Western worldview were established as a universal ontology and epistemology during colonial times, becoming the dominant lens for the world -Ontology refers to what exists (what is reality), and epistemology refers to how we know things (how we acquire knowledge and understand the truth).

Additionally, values of the Western worldview such as anthropocentrism or nature instrumentalization have also leached into the prevailing sustainable development paradigm (Torres, 2022). Sustainable development (SD) aims to ensure that wellbeing of the planet and future generations. However, a key issue with the SD approach is its strong focus on economic growth, which often involves increasing resource consumption and its tendency to promote offsetting the effects of economic activity on the natural environment through technology instead of prevention. This reflects western values conducive to increased extractivism, instead of addressing deeper issues on externalization, overconsumption, and absence of a sense collectivity (Carrasco-Miró, 2017; Indriyanto, 2023; Vásquez-Fernández, 2020).

Contrastingly, indigenous sustainability principles based on the spiritual interconnectedness of all aspects of material and immaterial reality have yielded natural and community-preserving outcomes for millennia, which have been applauded as conducive to our modern sustainability goals in recent decades (Throsby and Petetskaya, 2016). Although Indigenous practices have traditionally helped maintain sustainability in their communities, they are not fully included in the broader sustainability framework. Indigenous knowledge and worldviews related to sustainability are still largely overlooked in policies and global strategies (Buschman, 2021; Mazzocchi, 2020; Rajput and Jadhav, 2023).

The decolonial theory provides the necessary backdrop for the condition of indigenous worldviews in Modernity (a term that implies the continuation of colonial legacies in the current era). As the theory poses, during European colonization, the colonizer’s actions and worldview were set as the standard since they were self-deemed as civilizing and valid over others (Escobar, 2011; W. Mignolo, 2008). The hierarchical position of the Western worldview has remained ever since as a remnant of colonial dynamics. Furthermore, this colonial attitude that continues patterns of Western knowledge preference affects previously colonized populations, which are seen through a distorted cultural lens, creating a vicious cycle that reinforces the cultural hierarchies ruling the world today (Castro-Gómez and Grosfoguel, 2007; Glück, 2018; Maldonado-Torres, 2016).

Thus, as decolonial theory suggests, the Western worldview is privileged, a worldview that tends to be biased toward objectivism and efficiency, ignoring the communal and interpersonal knowledge’s significance. As a result, non-scientific knowledge and perspectives on the world are not held in the same regard as those derived from sequential scientific methods. In this way, Western culture, and its ways of producing knowledge became the global epistemic standard to be emulated. Thus, other worldviews and ways of organizing society are not considered equally va-lid to their Western counterparts (Escobar, 2019).

Therefore, the decolonial movement draws from knowledge and lifestyles from the Global South (a conceptual construct to refer to all the people of the globe that were formerly colonized) to «de-link» from the colonial power structures in an attempt to untie cognitive hierarchies so all forms of knowledge and lifestyles can be validated (Mignolo, 2007). The movement calls for representation spaces for historically culturally oppressed groups like Indigenous peoples to counterbalance pervasive marginalizing structures and a focus on local knowledge to generate alternative venues typically underlining indigenous values of conviviality to counter-hegemonic market individualistic values so that different cultures can have intercultural dialogues (Querejazu, 2016; Walsh, 2007).

Against this background, the sustainable development paradigm and many of its policies are typically derived from Western scenarios and thus influenced by their values (Arora, 2022). In contrast, sustainability principles from indigenous Global South worldviews tend to be less practically valued, less widespread, and not integrated into predominant sustainability policies (Asher, 2013; Frandy, 2018).

In this line, there has been a growing concern about exploring the relationship between worldviews and cultural values on sustainable development and the reasons for the differences in sustainability results between different human groups (Hiebert, 2008; Poonwassie and Charter, 2001; Urzedo and Robinson, 2023).

Additionally, research on sustainable development often overlooks how worldviews shape the adoption and implementation of sustainability (Banerjee, 2003; Diesendorf, 2000; Vasseur and Baker, 2022). Additionally, few studies explore Indigenous worldviews and their potential contributions to sustainability. Thus, this study compares Global South Indigenous sustainability principles with Western values, revealing how Indigenous perspectives offer unique, sustainable practices capable of fostering sustainable transformations.

2. Methodological aspects

A literature review with systematic elements was employed (Knopf, 2006). Additionally, the Web of Science database was used to uncover relevant literature on worldviews and indigenous sustainability. The research went beyond traditional databases due to their limitations in offering comprehensive examples of indigenous sustainability principles and acknowledging the prevalent Western bias in published findings. Similarly, databases like Google Scholar and SciELO were used, with a focus on including indigenous academics and other authors from the Global South.

The main unit of analysis consisted of scientific articles, followed by books, as well as web and news searches. Using the terms «Decolonial,» «Sustainable development,» «Buen Vivir,» and «Western culture,» «indigenous conservation principles,» and «sustainability challenges» a search for papers published from 2015-2024 sorted by articles in Web of Science was undertaken. Using the same set of keywords, a Google Scholar search, limited to peer-reviewed papers from 2003-2024 was made. For SciELO, the search concentrated on titles starting in 2010-2024 including the terms «Sustainability,» «Buen Vivir,» «Modernity» and «Worldviews». All of the former resulting articles comprise the universe for this literature review, from this universe a sample of 60 articles were carefully selected according to their relevance. Furthermore, some important works on «Decolonial Theory» outside of the former year ranges were included because of their importance for the topic.

Sources were selected using principles of the PRISMA method which stands for Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) (Sarkis-Onofre et al., 2021). This process included four main steps: identifying articles using broad search terms, screening to remo-ve duplicates and unrelated materials, checking eligibility by assessing quality and relevance, and finally, including only the most relevant studies for this paper.

The analysis centered on finding prevalent patterns and differences throughout the literature and throughout the sources. Then a narrative synthesis technique was used to condense and analyze the results (Lisy and Porritt, 2016). The research process and its expression in this article adhered to ethical standards in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Code of Conduct for Journal Editors (COPE). These guidelines ensured ethical research outcomes at every step of the process.

3. Different lenses different lifeways

To grasp the impact of values on the formation of sustainability concepts, this section delves into worldviews, considering that moral and ethical beliefs are deeply rooted in them. Understanding the disparities between Indigenous and modern lenses of the natural world and society is important to identify how these differing perspectives shape their respective understandings of nature and socioeconomic organization.

A worldview or cosmology is a set of beliefs about physical and social realities that can significantly influence behavior (Koltko-Rivera, 2004). The concept refers to a system of values and creation myths that affect ideas, motives, and behavior and are expressed through ethics and philosophy, shaping economic structures, customs and how communities perceive the universe and relate to other people (Blair et al., 2024; Johnson et al., 2011). In simpler terms, a worldview is a complex belief set about the placement and interaction of humanity with the inner world and cosmos.

There are considerable differences between the Western and Southern worldviews. However, this study will further expand on Southern worldviews (indigenous worldviews from the Global South), which in many cases differ from the worldview found throughout the Global South, especially in Southern metropolitan areas that have been more heavily influenced by modernity. It holds a mix of a Western emulating worldview cohesive with global standards. Nonetheless, many traditional values and philosophies continue to shape the Global South. It is also important to keep in mind that these descriptions do not imply that all Western or Indigenous communities have identical or homogenous cosmologies; instead, they represent common shared traits.

3.1. Modern Western Values and Worldview

Since it serves as the preeminent and most influential foundation for our civilizational culture, the Modern Western worldview will only be briefly described (Domptail et al., 2023; W. Mignolo, 2007). The use of the terms «Modern Western values» refers to those traits that underpin the Western worldview as seen by the decolonial school (Dussel 1993; Escobar, 2003; Quijano, 2019). These values such as individualism, instrumentalism, equality, rationality, materialistic philosophy and anthropocentrism shape a particular vision of the world associated with the West.

The Western Worldview is a perspective that emphasizes individualism, rationality, and the separation of humans from nature, often prioritizing economic growth and technological advancement. A core principle of the Western worldview is the distinct separation between humans and their surrounding environment, linked to the Judeo-Christian creation story in which God ascribes man the authority to govern the land and establish dominions over all creatures. Consequently, in Europe, man was granted the prerogative to subjugate nature to his desires and needs, thereby elevating men above all other life forms (Elizalde, 2022).

As a result, nature is often perceived primarily for its utilitarian value, viewed as separate and external to human beings (Barahona Néjer and Añazco Aguilar, 2020; Domptail et al., 2023). The relationship with the natural world is established through a perspective of instrumentalization, where interactions are characterized by dominance and control. Similarly, this worldview is marked by distinct divisions based on materiality, resulting in dualistic divisions, such as human/nature, individual/community, reason/emotion, and the compartmentalization of knowledge into specialized fields (Mignolo, 2021; Quijano, 2019).

The Western worldview is shaped by the intellectual legacy of philosophers such as Socrates and René Descartes. Descartes’ famous phrase «Cogito ergo sum» or «I think, therefore I am» highlighted the importan-ce of rationality (Elizalde, 2022). Later, philosophers in the 18th century emphasized the value of independent thinking, personal freedom, and individual wants (Woodley, 2022). When rational thinking became the main way to obtain knowledge, it led to a shared agreement on similar logical ideas and beliefs. Any ideas that opposed this view were often considered irrational (Dussel, 1993).

Additionally, in the Western worldview, characterized by rationality and individualism, there tend to be a belief that there is only one truth, which is determined by science, as described by Western scholars (Mignolo, 2007). Similarly, this worldview’s prioritizes individuals over society. As individuals adopt and reinforce the belief that humans are separate from nature, society becomes composed of people who seek their own potential and well-being independently (Domptail et al., 2023). In this context, land and its resources are seen primarily as tools for exploitation (Gudynas, 2015).

This situation gives rise to a «machine world» that is divided into multiple parts, with detachable and re-attachable parts created by individuals actively seeking their own goals. In this machine world, riches are sought for personal individual gain, and an economic framework develops that allows individuals to secure their own material well-being (Elizalde, 2022; Osadcha, 2021).

Similarly, the focus on a divinely bestowed unique position of humans, results in an anthropocentric worldview that prioritizes human life over other non-human life. Though, this worldview promotes the idea of equality among individuals bit can struggle to accept diversity due to beliefs in the existence of only one valid epistemology and one absolute truth (Escobar, 2019). Consequently, this leads to intolerance and the dismissal of any deviation from accepted norms (Querejazu, 2016).

Later, the justification for divine human superiority was substituted by the argument of human rationality, which assumes humans’ ability to make valid judgments that warrant them in a merited position above all other living forms (Grosfoguel, 2016). Thus, the sacredness of relationships and subordinate position of people below God and nature are disregarded.

Ultimately, human rationality superseded and displaced faith and spiritual matters in terms of validity (Woodley, 2022). Hence, the rule of rea-son now prioritizes scientific methodology and objectivity, indicating that comprehending the material world necessitates rationality and can only be deemed «valid» when approached via it (Aparicio et al., 2018; Escobar, 2003). Considering that human beings occupy a central position in the hierarchy of life and are hierarchically above other life forms, humans are detached from their surrounding environment, which includes the resources and tools necessary to meet their needs.

The dichotomy between humans and nature, as well as the compartmentalization of knowledge, makes this worldview characterized by a distinct divide between the physical and non-material dimensions, a divide that is also evident in other aspects, such as the experience of time (Osadcha, 2021). Time is markedly linear and exhibits distinct demarcations between the past and future. As a result, it is organized and classified, leading to a greater emphasis on previous historical events and a tendency for cultures to be more future-oriented (Grillo Fernandez, 1993; Nieto Olarte, 2022; Osadcha, 2021).

3.2. Indigenous Southern worldviews

An Indigenous worldview is a holistic perspective that values interconnectedness with nature, community, and spirituality, emphasizing respect for all beings. Indigenous worldviews from the Global South have diverse creation myths, but tend to share a common theme of nature as a nurturing «Mother.» Trees and animals are viewed as spiritual relatives and teachers, emphasizing the interconnectedness of all living things (Barahona Néjer and Añazco Aguilar, 2020). Additionally, in these worldviews, it is essential to understand one’s surroundings to understand oneself.

Several Indigenous societies across Africa, Oceania, Asia, and the Americas share similar beliefs in the interconnectedness of the cosmos (Alokwu, 2015; Frandy, 2018; Mazzocchi, 2020). They view the cosmos as a single reality that encompasses both visible and unseen forms, and human existence is seen as being intertwined with nature and the divine. This sense of belonging is deeply ingrained in their cultures and shapes individual behavior (Barahona Néjer and Añazco Aguilar, 2020).

Likewise, interconnected concepts characterize these worldviews and enrich our understanding of Indigenous perspectives. For instance, Buen Vivir, from South America, is a philosophy that advocates for collective well-being, while Sumak Kawsay emphasizes ecological sustainability and cultural integrity. Ubuntu, a Southern African philosophy, highlights mutual care and interconnectedness, while the term pluriversal recognizes the coexistence of diverse worldviews and knowledge systems.

Other principles, words, and phrases of Global South Indigenous groups also illustrate this interconnectedness. North American indigenous phrases like Aho Mitakuye Oyasin or hishuk’ish tsawalk (every aspect is unity, or all creatures are united) suggest that all that exists is part of an entireness since everything is made of the same essence or «life breath» (Mazzocchi, 2020). Thus, there is no human over nature or its fellow humans; as an individual, livelihood is only sustained by other life forms - communities and mother nature.

Likewise, another concept that expresses this idea is found in groups in South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. The concept of Ubuntu - humanity is found in others- points to a universal link that unites all humanity and all non-humans. Relatedly, the Mayan expression «In Lak’ech / Hala Ken,» «I am another you, you are another me,» incorporates this idea (Gonzalez, 2016). Thus, everything in existence is threaded by a common life thread, as the mythology of Amazon groups would put everything is the same, only our biological suit distinguishes us from trees, cassavas, and group members (de Castro Eduardo et al., 2004).

Consequently, the interactions between different living forms are founded on reverence and mutual exchange, resulting from the belief in the sacredness of all existences and the recognition and acceptance of their interconnectedness. Given that humans are positioned horizontally in relation to other life forms, they typically express gratitude to nonhuman beings who provide them with food and other essential supplies. This notion of mutuality, as represented by the Bantu word «kosalisana,» refers to the concept of reciprocal nurturing and service within a community. This includes the relationship between the elements of Mother Earth and human beings (Mazzocchi, 2020).

Therefore, reciprocal relationships arise when individuals internalize the significance of preserving the delicate equilibrium of life on Earth to ensure its ongoing sustenance. This translates into a recognition of the value and benefits that nature offers, together with the understanding that these benefits should be cherished and distributed rather than owned (Escobar, 1996). Therefore, the connection with nature is founded on sacred veneration, to the point where in specific communities, the term for plants is equivalent to those who nurture and protect us (Blair et al., 2024; Kimmerer, 2013).

Thus, Mother Earth is a living creature with intelligence and feelings (Domptail et al., 2023). This can be observed in relationships between humans and other life forms, as in traditional practices such as consulting nature for consent before taking life from it when cutting a tree or hunting, or even talking to nature as a living being -many cultures talk to trees, rivers, and animals- as a way to show respect for other lifeforms (Mika et al., 2024).

This awareness of life’s interconnectedness puts the community at the center, and people work for collective welfare and needs. Humans view their place as a collective rather than an individual, and their «community» includes wildlife, mountains, and ancestors (Artelle et al., 2019; Frandy, 2018). These worldviews, especially in the Americas, equalize and connect sentiments and reason, allowing humans to think with their minds and hearts, feeling and thinking «sentipensar» (Escobar, 2019). Similarly, Andean cosmologies use emotions and intuitions to determine reality (Gonzalez, 2016).

From dust to planets to the unseen, reality is a web of multifaceted processes. Materiality is just a small part of a larger reality based on our awareness and limited understanding (Fuentes González, 2014). Since subjectivities and uncertainties are valid knowledge pieces, absolute facts and objectivity lose their significance. A holistic understanding is preferred to compartmentalizing knowledge (Nieto Olarte, 2022; Woodley, 2022).

Under this view, nature has an intrinsic sacredness and people interact reciprocally with it. In that regard, there is tolerance for diversity and room for multiple truths, given that truths are based on individual experiences (Domptail et al., 2023; Escobar, 2019; Woodley, 2022). The acceptance of the divinity within all beings implies that everyone teaches and learns from other living beings while accepting their differences (Waldmüller et al., 2022). Thus, community norms strengthen this interconnectedness, while spirituality and connections serve as sources of identity (Woodley, 2022).

In these indigenous worldviews, the valuation of life is based on the belief that life is sacred. With these clear principles of «life-centric ethics,» it is difficult to objectify Mother Earth. Furthermore, a sacred and reverent relationship with nature results not only in a responsibility to care for it, but also in respect for its cycles and regeneration rate. Many indigenous practices reflect the principle of taking only what is necessary from nature and allowing its regeneration cycles to continue (Mazzocchi, 2020). For example, the Iroquois community follows «the seventh generation» principle, which states that each generation’s activities should result in the same conditions seven generations later (Deul, 2022).

3.2.1. Contrasting Perspectives: worldview comparison

This subsection briefly examines the worldviews of Indigenous peoples and modern societies and how these perspectives influence environmental stewardship and community well-being.

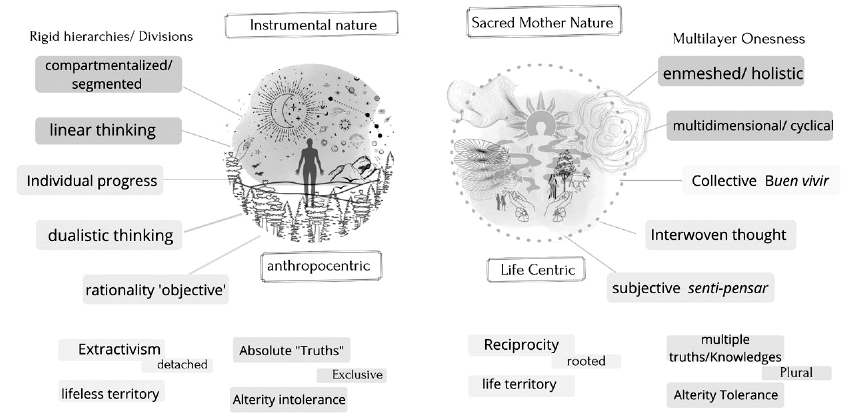

As seen in Figure 1 both worldviews differ significantly, as depicted in the illustration, the Western anthropocentric worldview tends to see nature through an instrumental lens -and reality, through marked divisions. In contrast, Indigenous perspectives view humans as part of an interconnected system with diffuse boundaries, where nature -an all-encompassing provider and life are sacred. Represented by open hands, a reciprocal nature-human relationship includes multiple life forms -trees, animals, and even inanimate elements-valued as part of the life cycle. This view supports alternative ways of knowledge, such as subjective «think-feel» approaches, fostering reciprocity where even the inanimate is seen as alive, creating a sense of rootedness in the community and land.

Additionally, because life is viewed as an ongoing process in the indigenous worldview, future and past events are not overemphasized and are less important than the movement of life in the present (Elizalde, 2022). It is also worth noting that these worldviews have very diffuse time or materiality distinctions, whether material or spiritual; the future or centuries ago are intertwined in the unity, as seen in Figure 1, these cosmologies regard reality as continuous, subjective, based on unity, and containing numerous layers of time, and matter. In contrast, the Western approach favors a fixed, and distinct division of time, history, hierarchies, materiality, and immateriality.

Figure 1 also depicts the differences in some of the ontologies and epistemologies (what exists and how we know reality) maintained by both worldviews, as well as their perspectives on knowledge and socioeconomic order. In the first, anthropocentric scientific rationality reigns supreme, with positivistic scientific knowledge representing the sole source of valid and individual-based social interactions that sustain individualism, competition, and personal maximized utility. In the second worldview, a biocentric rationality -a sacred relationship with nature and community is observed, as evidenced by local exchange, communal living, collective resource management, and in which knowledge is complex, lacks a specific structure or method, and is open to the knowledge of other communities (Querejazu, 2016; Woodley, 2022).

Nevertheless, since Western civilization’s worldview is closely aligned with the values of Modern society, its principles are deeply ingrained in thoughts, behaviors, and customs, consistently being reproduced today (Grosfoguel, 2008; Mignolo, 2021).

The former has been conducive to nature’s relegation to a subordinate role as a provider of resources in socio-economic paradigms. This is also why social organization is built on divided concepts of reality, reason, and objectivity, and why there is a widespread reliance on positivism to determine the validity of knowledge (Grosfoguel, 2008). While objective rationality is still the dominant foundation of knowledge, it is important to acknowledge that even in the context of modernization -as indicated by southern cosmologies, human experience and knowledge continues to be immersed in subjectivity and relationality.

3.2.2. Embracing indigenous sustainability principles

The widespread instrumentalization of nature has endangered around one million species in the last several centuries under the modern cultural logic (UNSDN, 2021). Additionally, this disregard for nature has increased the need to promote alternative sustainability proposals, especially from Indigenous groups in the Global South.

This is because Western values might be less prone to translate to stewardship and preservation, restricting the sustainability paradigm’s ability to evolve. Thus, Indigenous sustainability approaches are needed. Most alternative sustainability proposals and perspectives from the Global South draw from and revive Indigenous communities’ knowledge base, grounding their proposals on important customs and ethical precepts from these ancestral communities (Leff, 2012; Patiño Castro et al., 2023). Therefore, oppressed, and underprivileged communities, instead of elite institutions, inform Southern sustainability solutions.

According to UNSDN (2021), being only five percent of the population, Indigenous people are the original conservation experts since they preserve eighty percent of the world’s biodiversity and forty percent of terrestrial protected areas, maintaining them mostly intact since maintaining the welfare of both human and non-human life is ingrained in their way of life.

Therefore, sustainability is profoundly ingrained in indigenous Southern worldviews and ethics. In fact, sustainability -a system or quality of respecting nature’s cycles- is so ingrained in these traditional communities that an equivalent term to sustainability does not exactly exist, as it is part of the being of these communities (Sánchez De Jaegher, 2018).

The reason for their remarkable ability to sustain and prosper over multiple generations without degrading their land is intricately linked to their worldview, which fosters a deep connection with the natural and spiritual realms (Frandy, 2018). Based on these principles, their only options is being sustainable, as they primarily align with natural cycles.

It is then important to remember that the principles presented in Global South sustainability proposals are ideas about sustainability based on Indigenous cultures rather than a specific sustainability plan.

While diverse, Indigenous sustainability perspectives share many and tend to be multicultural and eco-centric (Kothari et al., 2019). Southern sustainability ideas form a pluriverse of worldviews that seek mutual wellbeing, promote degrowth, and propose a reciprocal society-nature relationship, in contrast to SD that typically emphasizes growth, utilitarianism and anthropocentrism

Thus, Indigenous perspectives consider nature and community as essential, deriving from civilizations that act in reciprocity with their land with strong communal bonds and a sense of belonging.

For example, sustainability proposals rooted in Sumak kawsay or Buen Vivir, which translates to «good living» or «living life to the fullest» in Quechua (Macau), portray a diverse community lifestyle centered around ecologically balanced collective advancement. This lifestyle values the interconnectedness of Pachamama (mother earth) and holds its rights in high regard (Capitán et al., 2019).

Thus, good living economies are characterized by sufficiency, balanced production that does not cause harm to the environment, and a refusal to engage in the exploitation of others (Jimenez et al., 2022; Unceta, 2014). Additionally, other proposals, such as Ubuntu and Swaraj, share similar objectives and methods. Ubuntu is a principle based on a collective African sense of reciprocity, and Swaraj is an ecological democracy proposal in India (Dasa, 2021).

Likewise, proposals based on the above principles are characterized by collaborative and communal living arrangements that prioritize community reciprocity, and circular habits. These proposals embody the concept of sustainability as a principle knitted in their lifestyle instead of a goal to be attained.

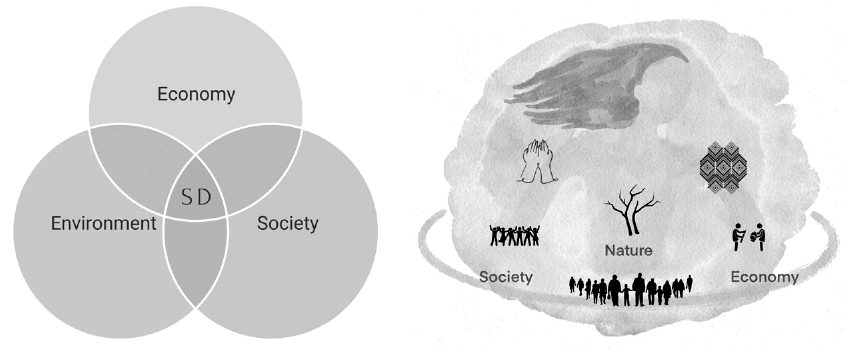

Hence, as depicted in Figure 2, there exist strong connections between sustainability and Indigenous worldviews. Contrastingly, the present-day sustainability paradigm lacks ethical norms for nature or earth ethics (Diesendorf, 2000; Frandy, 2018).

As shown in Figure 2 in indigenous sustainability perspectives, Mother Nature contributes everything to society and the economy. The two hands represent the reciprocal relationship between nature and humanity; unclear lines illustrate that all are intertwined, and the circular ring symbolizes how the balance of this harmonious dynamic is sustainability.

Additionally, the concept of sustainability differs between the two viewpoints, in contrast to the dominant sustainability paradigm that aims to achieve a harmonious equilibrium among three dimensions. From a Southern Indigenous perspective, this would be considered a contradiction to the fundamental principles of reality. This is because communities, their interactions, and other living entities (such as people, economy, and nature) are intricately interconnected, and the economy, if anything, is a part of society (see to Figure 2).

Given the ecological issues and the necessity for alternative solutions, there has been a growing need for the adoption of sustainability proposals derived from holistic worldviews (Barahona Néjer and Añazco Aguilar, 2020; Domptail et al., 2023; Snow and Obed, 2022;).

Additionally, sustainability proposals from the South propose pluralistic thinking-based alternative approaches that aim to sustain all life forms, as well as foster an atmosphere of tolerance for diverse future possibilities (Querejazu, 2016). These proposals advocate different strategies for structuring society and the economy, not as templates to be copied, but as ways of life.

Despite the multitude of proposals originating from the global South, they exhibit similar characteristics and concepts. They usually represent attempts to challenge the fundamental values of Eurocentric cultural logic in modernity through decolonization. The proposals emphasize new alternative meanings for important societal terms. Similarly, they disrupt the structure of contemporary institutions by shifting power dynamics from top-down to bottom-up. They also place value on communal management of society and economies and aim to eliminate binaries to restore harmonious relationships between land and humans (Ajwang et al., 2022).

These sustainability transformation proposals offer alternate interpretations to a contemporary comprehension of social terms, aiding in the decentralization of terminologies and language from Eurocentric notions. Additionally, they revive concepts that are beneficial to reinforce communal and suppressed understandings of society. For example, concepts or meanings that have not gained widespread recognition because they are overshadowed by colonial terms.

One such example is the Zulu term for democracy, «umbusu want,» which signifies «a rule by the people,» but also conveys the idea of «good life or autonomous living» (Arora, 2022). Another example is the Maori term «Whenua,» which represents both land and placenta, symbolizing the interconnectedness between humans and nature (Watene, 2022).

They also use cultural and organizational traditions suppressed by modernity to re-signify and deconstruct modern institutions. For instan-ce, as illustration of this phenomenon are the Zapatista autonomous councils’ «governing by obeying,» a self-government movement that obeys people’s voices and socially negotiated principles such as serving others, social justice, equitable local economy, respecting peoples’ will, ecosystem regeneration, proposing and not imposing, working from down-up, multiethnic dialogue and rotating authority figures (Maison, 2023; Romero, 2023).

In these proposals, community is at the center. Social and economic organizations depend on communal management, sufficiency, local exchange, thus revaluing suppressed traditions. They emphasize reciprocity, caring, and solidarity in harmonious interactions with other beings, including non-humans, resulting in a web of deep relationships amid modern society’s individualization (Ciofalo, 2022; Queirós, 2003).

Additionally, these proposals reconnect humans with nature by reviving animism and practices like «sentipensar,» a thinking-feeling relationship with Earth organisms (Escobar, 2019).Traditional stories and customs are used to legitimize nature’s rights in several proposals inspired by marginalized indigenous traditions, for instance, the revival of the tradition of saying good morning to the liter tree to show respect and to avoid getting allergies from the tree in the Mapuche communities of Chile (de Castro Eduardo et al., 2004). Despite what might seem to be a superstition-derived practice, there is a recognition of life in trees and other natural elements as entities with life and with whom one forms relationships.

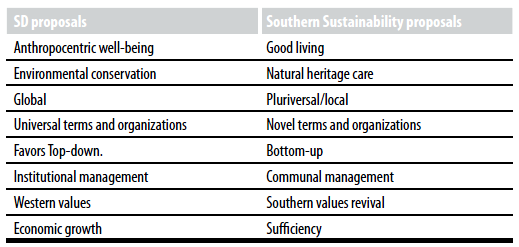

In these ways and as Table 1 illustrates Southern sustainability approaches challenge traditional structures and transcend existing divisions and artificial distinctions between society, science, and spirituality.

Table 1 displays some defining traits of the Southern sustainability proposals compared to those based on the SD paradigm.

Although Southern Sustainability is made up of a wide range of Indigenous contributions, they may all be categorized within the «Buen vivir» scope, as they adhere to shared ideas of what constitutes a desirable way of life.

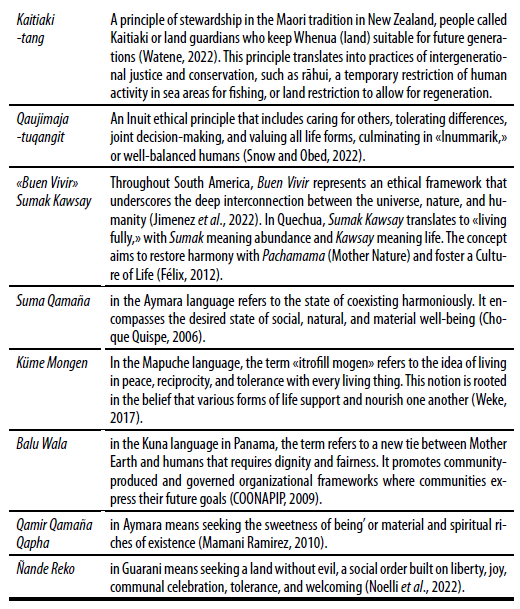

They have been adopted and proposed by various Indigenous cultures, both within and outside of the Americas, under the concept of «Buen vivir». Table 2 demonstrates the correlation between these principles and land utilization, economic well-being, and contentment in life. Several examples of Buen vivir include:

As depicted, Buen Vivir serves as the shared philosophical principle guiding communal thought and behavior in all these southern principles of sustainability. In this sense, indigenous conceptualizations of sustainability centered around the idea of «Good Living» adhere to a holistic understanding and an openness to new paths.

Within them, the harmonious arrangement of existence, encompassing both societal and economic aspects, is not dictated by human beings, but rather by the forces of nature. Thus, nature assumes an active role (Domptail et al., 2023; Haila, 2000). Materialism and detachment do not shape their perception of surrounding elements; instead, they are experienced through the lens of unity, challenging the modern distinction between society and nature.

Similarly, well-being depends on the health of the whole community, including both people and non-humans (Mazzocchi, 2020). Additionally, despite its traditional beliefs, Southern sustainability frameworks remain open to western science and other forms of knowledge if they benefit the community (Gudynas, 2011). As interculturality, a multiplicity of knowledge, underpins its acceptance and valuing of diverse knowledge.

3.2.3. Practical Applications of Indigenous principles

Despite their eco-social benefits, Indigenous proposals face significant application challenges in a world dominated by Western values and indigenous peoples marginalization, including inadequate government inclusion, resource exploitation, pollution and cultural marginalization, as both public and private projects often disregard Indigenous sustainability principles and living land rights (Alipaz Cuqui, 2022; Tiburcio Cayetano, 2022). These factors hinder effective implementation, as they threaten Indigenous autonomy. The solution then lies in increasing Indigenous autonomy and their voices to implement their sustainability principles (Cruz, 2020).

Government support, funding, and entrepreneurship can help Indigenous communities gain autonomy and resources they need to promote their values. This support should also be targeted at implementing and making indigenous values more visible and enabling them to exist alongside or even influence mainstream cultural practices.

Despite the difficulty in changing dominant mindsets, the communal values of Buen Vivir and Pachamama’s harmony are not just idealistic ideals; there are several ways in which they can and are being implemented by communities resisting oppressive structures and reasserting indigenous ideals (Ciofalo, 2022). Many of the alternate community proposals inspired by Buen Vivir represent real-world examples of economic and community reorganization.

An extensive web of social movements, including agroecology, the circular economy, and the solidarity economy, have created a rich network of resistance movements in the Global South (Maison, 2023; Patiño Castro et al., 2023).

For example, a collection of ecological and solidarity businesses in Chiapas, Mexico, are examples of nature-caring, community-oriented solidarity economies that are based on Southern sustainability principles (Fuentes González, 2014). Under the name of Yomol A’tel, which translates to «we work together and dream,» these cooperative-like businesses are founded on social justice, community agreements, and territorial preservation.

Other tangible examples at the government and business levels show how these sustainability principles can be applied in areas where modernity has altered traditional Indigenous ways of life.

In terms of practical application, some programs have implemented these principles at the government level. For instance, the South African government’s Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKS) Programme integrates Indigenous knowledge into science and technology -traditionally Western-dominated fields- promoting research based on traditional practices such as oral tradition and conservation (Department of Science and Technology, 2004).

Ecuador and Bolivia enshrined Buen Vivir principles in their constitutions, defining it as a sustainable development goal that includes the Rights of Nature (Ecuador, Art. 72, 275). This framework encourages community-centered sustainability in these contries, yet conflicting ecological and economical goals and economic dependence on extractive economies hinders full implementation, underscoring both the aspirational nature and transformative potential of Buen Vivir in the region (Gudynas, 2011).

Another example is Whānau Ora (Māori for «healthy families») a government health services initiative in New Zealand driven by Māori cultural values. It shifts the focus from individual health to empowering whānau (family groups) and the community as collective decision-makers, promoting localized sustainable solutions in urban spaces (Te Puni Kōkiri, 2024).

In urban contexts, Indigenous values can also be applied through partnerships with local governments to incorporate Indigenous knowledge in urban planning. For instance, Toronto’s «Urban Indigenous Strategy» and Australian legislation aim to integrate and safeguard Indigenous values and traditions into city spaces, governance, and services (City of Hamilton, 2024; Landscape Australia, 2024).

In the business field, some practical examples that effectively implement Indigenous values in their business fabric and client relations include: Kāhui Tautoko Consulting Ltd (meaning a group sent out to uplift others) is a New Zealand consulting firm run by Indigenous people and based on Māori values that leads with Indigenous sustainability principles for their clients (Kahuitautoko, 2024).

Likewise, Nii Biri («Wonders of the Forest» in the Shipibo-Conibo language) a social enterprise run by Indigenous people in Peru that markets crafts and wood products, integrating traditional knowledge and prioritizing communal prosperity (Nii Biri, 2024).

Adititonally, Lol Koópte’ (meaning «flower of circinate» in Maya) a furniture business in Mexico, run by Maya women, uses leftover timber, emphasizing respect for Mother Nature and regenerative production awareness (Estrada, 2024).

In a similar vein, common people from the Global South, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, are challenging the shortcomings of the current sustainability interventions and providing a definite, tangible substitute of ecological rationality for energy transitions and circular solidarity enterprises (Post, 2022; United Nations, 2021).

Accordingly, since they defy the cultural logic of modernity and challenge the mindsets that feed the ecological problem, these expressions of Southern sustainability represent a decolonial delinking of mainstream sustainability. Similarly, they depart from the notion of a single SD illustrating not just one but multiple possibilities since these proposals make no pretense of unifying the ideas and interests of all parties. In doing so, they accept variety and otherness, as well as a future that is «heterogeneous» and bio-culturally diverse, much like the material natural world (Leff, 2012).

4. Discussion

The study compared Indigenous and modern worldviews and their takes on sustainability. It also highlighted indigenous principles under the banner of Buen vivir and exemplified the potential benefits of adopting Indigenous values in finding collaborative solutions and changing unsustainable values.

As observed, the lens through which the world is seen affects how humans live and relate to it and molds their respective lifestyles. Adoption of the values of indigenous worldviews and their philosophical shared cornerstone of Buen vivir can translate into sustainability action and novel ways of creating community well-being.

The findings, in line with other studies, imply that worldviews can influence individual and organizational actions and that Indigenous values can offer insightful information for developing policy and business sustainable solutions (Goldberg, 2009; Gómez-Baggethun, 2022; Harriden, 2023; Hiebert, 2008; Odora Hoppers, 2021; Urzedo and Robinson, 2023).

According to the findings, indigenous values encourage sustainable lifestyles, and socioeconomic initiatives based on these values produce community and environmental benefits.

Likewise, the false divides in the modern worldview can further cement the idea of balancing two «separate» economic and natural spheres -the preservation of unsustainable lifestyles and preserving nature- limiting the recognition of human-nature interdependence and making holistic Southern sustainability harder to achieve and restricting Western sustainability science’s potential for large-scale impact. (Luetz and Nunn, 2023; Mazzocchi, 2020; Vasseur and Baker, 2022). In this line, the findings support the argument that the rupture of human-nature connections hinders sustainability transformations (Luetz and Nunn, 2023; Malik et al., 2021).

In this sense, as the results indicated, humanity’s sustainability dilemma is one of values that yield the disconnection from its spiritual dimension, ignorance of the interdependence of all life, and the artificial uprooting from the local ecosystem while still, though often blind to it, deeply rooted into place.

Thus, the integration of indigenous values can illuminate this reality, facilitate widespread aspirations to a Buen vivir lifestyle, foster an understanding of the interconnectedness of all life, and bring awareness of the human roots to place and an exhortation of respect and sacredness to this interconnectedness (Malik et al., 2021; McGregor et al., 2020; Throsby and Petetskaya, 2016).

Similar to these findings, other studies have also found that worldview adoption can influence sustainability action, and others testify to the sustainability-conducive outcomes of adopting Indigenous values even in non-indigenous contexts (Fuentes González, 2014; Galán-Guevara, 2023; Pavón and Macip, 2023; Post, 2022).

Likewise, incorporating the showcased indigenous worldviews and Buen vivir principles in sustainability agendas may influence global societies by promoting harmonious interactions with nature. Therefore, indigenous sustainability values should be integrated into the sustainable development paradigm.

Additionally, embracing indigenous worldviews has profound implications for both sustainability practices and policies. As exemplified by some Global South sustainability proposals and examples rooted in Indigenous values, by adopting holistic sustainability values, policymakers could legally recognize nature’s rights and foster business practices based on cooperation, new ways of conceptualizing social structures, and novel economic exchange practices. In this line, policymakers and companies could open spaces for genuine dialogue with Indigenous groups to learn jointly and create pathways for larger-scale, reciprocal ways of operating. Additionally, by incorporating values from indigenous worldviews, community organizations could increase their sustainability outcomes (Ciofalo, 2022; Lopez y Rivas, 2018; Patiño Castro et al., 2023).

Similarly, integrating Global South sustainability worldviews and proposals into prevalent sustainability strategies can help undo profound systemic knowledge and power hierarchies and promote cognitive justice by validating Indigenous people’s expertise and knowledge. Moreover, embracing Indigenous values can reshape consumer mindsets by emphasizing concepts such as human interconnectedness and rootedness to their local environment, tolerance of other cultures, and respect for the natural world, paving the way for more equitable and sustainable societies.

Nonetheless, embracing traditional Southern values should not be done out of a sense of idealized moral superiority but rather as a perspective equally worthy of acceptance and inclusion alongside Western sustainability science.

Thus, it is crucial to exercise caution not to idealize indigenous worldviews and sustainability principles as superior or assume they can be put into practice without major systemic resistance hurdles. As legacies of pluralistic intolerance are still present, implementing the values and beliefs associated with these worldviews on a large scale can be challenging if structural justice and pluralistic considerations are not addressed simultaneously (Harris, 2004).

Even for Indigenous groups, it can often be hard to sustain their cultural values. Due to inequitable social and economic structures in their lives, many Indigenous communities find themselves forced to compromise their values in favor of modern capitalist values for survival, leaving their communities for regular jobs and a necessity-driven abandonment of their culture (Patiño Castro et al., 2023). These situations further exemplify the need to embrace Indigenous values to decolonize both sustainability perspectives and oppressive structures.

Therefore, indigenous sustainability principles are needed for sustainability models that go beyond protecting against damage to the environment or setting rules for a limited but ongoing exploitative and oppressive relationship between people and nature (and themselves). As findings indicated, these worldviews and values are essential for social and economic organization structures that openly recognize the interconnectedness and value of all life forms.

As some of the practical sustainability manifestations of Buen Vivir in the South show perceiving nature as sacred and as part of oneself and the community yields favorable conservation results as self-preservation equates to ecosystem preservation, whereas there may be less incentive to do so from a modern lens that considers the ecosystem as necessary yet lifeless (Fuentes González, 2014; Jimenez et al., 2022; Lopez y Rivas, 2018).

Additionally, adopting collaborative intercultural solutions can make policymakers and businesses see community and nature with a different lens by recognizing their inherent rights and yielding a higher inclination to their preservation. For communities and businesses, it allows for the creation of new social structures and economic exchange practices and concepts that emerge from worldview syncretism.

As the need for sustainability transformations guided by genuine lifestyle and policy change becomes ever more pressing, understanding the role of worldviews in shaping sustainability action can help in developing effective strategies based on both Indigenous and Western values that counterbalance and reverse some of the current eco-destructive mindsets. In this way, this article proposes a pluralistic path to sustainability aimed at reducing unsustainable practices at individual and societal levels. Likewise, the study contributes to the existing literature on sustainability and worldviews, providing insights and empirical examples of the potential benefits of adopting Indigenous values in promoting sustainable behavior.

5. Conclusion

This study has argued for the importance of embracing indigenous worldviews for multicultural and effective local sustainability transformations to occur. Overall, indigenous worldviews are essential for human socio-economic activities that openly recognize the interconnectedness and value of other life forms and lifestyles attuned to the imbricated cycles of nature, allowing for the sustainable operations of all life forms. Likewise, this study suggests that organizations that adopt reciprocal indigenous worldviews could open novel paths of economic and social organization.

As the theoretical section outlines, Indigenous perspectives emphasize the importance of communal welfare and collective governance of societal matters such as health and the economy. This is illustrated by the example of Yomol A’tel, where community agreements fostered solidarity enterprises and environmental stewardship, or in Whānau Ora, where the community decides their collective health path.

Likewise, indigenous openness to different forms of knowledge can lead to cultural revival as exemplified by the South Africa Indigenous Knowledge Programme, which recognizes oral traditions as legitimate knowledge sources. Additionally, Indigenous worldviews also emphasize reciprocal relationships with nature which can foster sustainable businesses as demonstrated by Lol Koópte’, where the use of regenerative timber is coupled with teachings about reverence for Mother Nature, imparted to consumers.

These indigenous worldviews are not only relevant for Indigenous communities; examples shown in this article from urban policies, education, and companies based on Indigenous principles, demonstrate that their application is also viable and should be adopted in the private sector and in national and international policies. Practitioners can use these findings to develop policies that integrate Indigenous principles into urban planning, include Indigenous knowledge in education, and encourage businesses to adopt regenerative practices while educating customers on reciprocal relationships with nature.

Therefore, integrating indigenous worldviews can influence sustainability practice and policy and attain broader sustainability goals. The featured examples of sustainability proposals stemming from the Global South rooted in these Indigenous values attest to the success of adopting these values to create new forms of community economic and social Buen vivir by recognizing the sacredness and interconnectedness of everything, making sustainable actions second nature.

To address the limitations of this study, future research should consider employing empirical methods to ascertain the values that motivate community organizations in the Global South and offer additional insights into the impact of adopting a worldview or its components on local sustainability outcomes. Additionally, this topic could be expanded in the future with fieldwork research, highlighting the differences between Western and Indigenous paradigms. Likewise, future research is advised to study the impact of urban policy that reflects holistic indigenous values, in sustainability mindsets and consumer perception shifts in different countries.