Introduction

The aorta, the largest artery in the body, serves as an elastic conduit essential for transmitting arterial pressure throughout the arterial bed. This blood vessel, as well as those of medium and small caliber, are susceptible to the development of atherosclerosis due to a combination of acquired, hereditary, sex- and age-related factors 1. In addition to mechanically obstructing blood flow, atheromatous plaque presents risks of rupture leading to obstructive or embolic vascular thrombosis.

Shaggy aorta (SA) represents an extreme manifestation of aortic atherosclerosis, characterized by extensive and severe atheromatous disease featuring scattered ulcers, loosely held debris, a weakened medial arterial layer, and a tendency towards thrombus formation 2,3. While the precise etiology behind the heightened vulnerability of the aorta remains elusive, it is believed to involve complex interactions between hydrodynamic patterns affecting the aorta and genetic predispositions to atherogenesis 4.

The clinical importance of this pathology relies on the various syndromes that can develop from its etiopathogenesis, which generate great morbidity and mortality in affected individuals, and its utility as a risk factor of operative mortality. Furthermore, the advancement of diagnostic tools underscores the importance of the multimodality of images in achieving timely and accurate diagnoses, thereby facilitating appropriate decisions regarding patient management. Within this context, we review the nature of this disease, and the spectrum of different syndromes associated with SA.

Definition

A uniform definition of SA has not been established due to the different diagnostic methods used in its diagnosis; however, some definitions have been postulated. SA is a descriptive term that has been used for atherosclerotic aortic segments, which show localized or diffuse irregularity and typical obstructive and spiculated images that are visualized in different diagnostic tools 3. The shagginess is imparted by complications like multifocal ulcerations, calcification, and/or overlying thrombi 5. Another definition used for the SA is a diffuse, irregularly shaped atherosclerotic change involving 75% of the length of the aorta from the arch to the visceral segment with atheromatous plaque thickness greater than 4 mm, as confirmed by imaging tools 5. Clinically, it is often referred to as an imaging finding of contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) or echography 6.

Epidemiology

The prevalence and incidence of SA in the general population are unknown, however, it is estimated at 10-20% in certain risk groups. Thus, one study found that 48/447 patients (11%) having elective aortic abdominal aneurysm repair had SA. Also, the incidence of major complications and mortality was 4.1 times higher in patients with SA than in patients without a severe atherosclerotic aorta 7.

In another study, it was reported that the prevalence of SA in patients undergoing total aortic arch replacement was 19% 8. Likewise, it has been seen that most of the patients with SA are elderly, predominantly males-with comorbid conditions like hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary and peripheral artery disease, and stroke 5.

Regarding data in Latin America, a review conducted in Argentina emphasizes that the prevalence and incidence of SA in at-risk populations are unknown. It also describes the complexity of this pathology and its high morbid-mortality in affected patients 9. On the other hand, in Mexico, an ambispective study was conducted in which a prevalence of 8.66% was determined, a mean age of 70 years, predilection for the male gender, and the main comorbidities found were similar to those previously described 10. Unfortunately, there are no epidemiological data on AS in Peru; however, there is a Peruvian review on aortoiliac occlusive disease, which describes the association between AS and poor prognosis and high risk during endovascular treatment 11.

Pathophysiology

Severe atherosclerotic degeneration of the aorta is a multifactorial process associated with various modifiable risk factors and non-modifiable. The initial event that gives rise to atheroma formation is unknown; however, the “response to injury” hypothesis considers atherosclerosis as a chronic response of inflammation and scarring in the arterial wall after endothelial injury with subsequent evolution of atheroma due to the interaction of modified lipoproteins, the immune system and the smooth cells of the arterial wall 1,12-14.

After the accumulation of lipoprotein particles in the subintimal space and their binding to proteoglycans, these particles are affected by oxidative stress (oxidation and glycation). These modified lipoproteins induce the synthesis of cytokines that promote the chemotaxis of inflammatory cells (monocytes, T lymphocytes), phagocytizing this material. These macrophages (foam cells) are a source of new mediators that favor the migration of smooth muscle cells toward the intima, which are responsible for the elaboration of extracellular matrix that accumulates within the atherosclerotic plaque (allowing its growth) 1,4,12-14.

The spatial heterogeneity of atherosclerotic lesions in patients with SA has been difficult to explain. It is believed that this is not only the result of a response to the different hydrodynamic patterns that affect the aorta (normal pulsatile lamellar flow generates greater shear force that is associated with lower atherogenicity) but also of a genetic predisposition specific to the individual 4. Thus, those with higher expression of genes coding for the enzymes superoxide dismutase, nitric oxide synthase and Kruppel-type factor 2 are less predisposed to severe atherosclerotic degeneration by reducing the formation of oxygen free radicals, inhibiting nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) and favoring vasodilatation 4,15-18.

Diagnostic implications

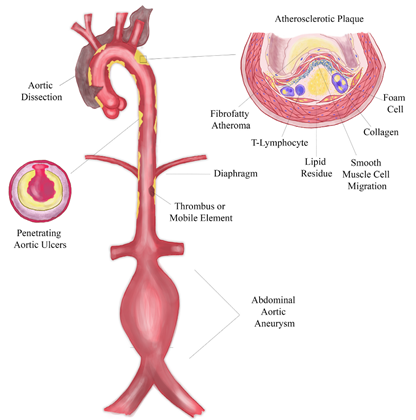

The clinical importance of this pathology lies in the various syndromes that can develop from its etiopathogenesis, including aortic dissection (Figures 1, 2; Video 1); aortic aneurysms (Figure 3; Video 2); thromboembolism or peripheral atheromatous embolization (to the digestive system, renal, spinal cord or peripheral limbs manifested as SA syndrome) (Figures 4, 5; Videos 3, 4), ischemic stroke and penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer 19 (Figure 6. Central Illustration). Likewise, SA is an independent and significant risk factor for operative mortality.

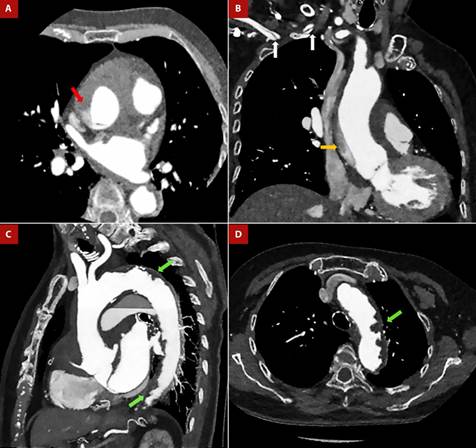

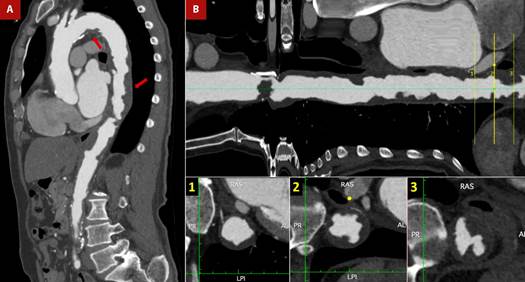

Figure 1 Anterior Q infarction in Shaggy aorta and Stanford “A” aortic dissection. An 80-year-old female patient was admitted to the emergency room with a diagnosis of a 3-day evolving anterior Q infarction. During the attempt to cannulate the left coronary artery, contrast retention was detected in the ascending aorta, so CT angiogram was performed. A, B. Dissection flap is seen at the sinotubular junction (red arrow), with an ascending trajectory to the proximal aortic arch (orange arrow) and extending through the brachiocephalic trunk to the proximal segment of the right subclavian artery (white arrows). C, D. Complicated plaques in the aortic arch and descending aorta (green arrows). Diffuse atheromatosis is observed at the aortic arch, with an image suggestive of an intraluminal thrombus.

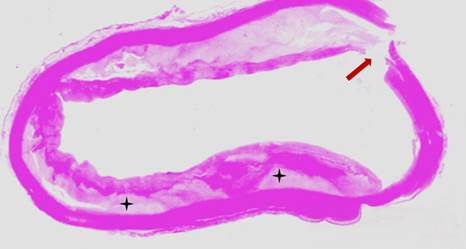

Figure 2 Microscopic view of the atheromatous ascending aorta. The patient underwent emergency Bentall de Bono surgery for acute aortic dissection Stanford A, however, died during the intervention. Circumferential atheromatous plaque in the ascending aorta, with cholesterol deposits in the subintimal layer (black asterisks). The aortic dissection entry flap can be seen (reddish arrow).

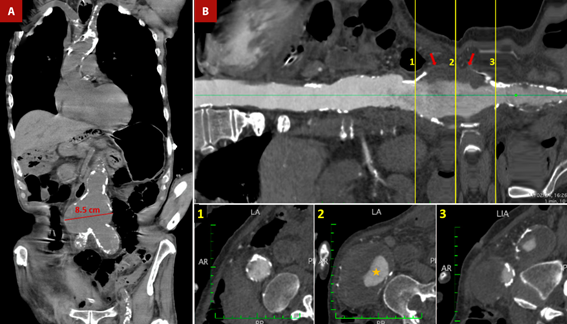

Figure 3 Shaggy aorta and abdominal aortic aneurysm. An 84-year-old male patient was admitted to the emergency room with severe diffuse abdominal pain. Medical history included hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease and senile dementia. A. Non-contrast thoracoabdominal CT - coronal section. Severe calcification of the aorta is observed, predominantly in the aortic arch and abdominal aorta. Also, there is an aneurysmal dilatation of the infrarenal aorta with a maximum diameter of up to 8.5 cm. B. Longitudinal reconstruction of the aorta. The transverse sections at the level of the abdominal aortic aneurysm demonstrate the calcification of the abdominal aneurysm wall, along with the presence of an extensive mural thrombus (red arrows) and a reduced luminal diameter (orange star). Mesenteric ischemia was suspected, with the emboligenic source coming from complex atheromatous aortic plaques or abdominal aortic aneurysms. The patient was admitted to the operating room for an exploratory laparotomy. However, the patient died during the operative procedure.

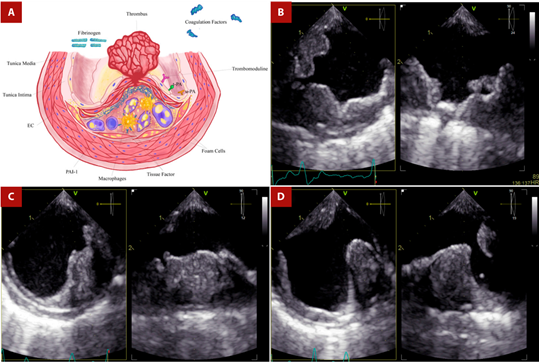

EC: endothelial cell; PAI-1: type 1 plasminogen activator inhibitor; SMC: smooth muscle cell; t-PA: tissue-type plasminogen activator; u-PA: urokinase-type plasminogen activator.

Figure 4 Shaggy aorta and thrombus. A. After rupture of the fibrous cap, coagulation molecules from the bloodstream come into contact with foam cells, tissue factor, and microparticles derived from apoptotic atheroma cells, triggering thrombus formation in the ruptured plaque. The thrombotic equilibrium will determine whether plaque rupture will culminate in the formation of a persistent, distant-migrating thrombus or in its dissolution. B. TEE - Proximal third of the descending aorta. Orthogonal images showing extensive mural thrombotic formation of irregular border that occupies up to one third of the arterial lumen, with small movable elements on its surface in the long axis. C. TEE - Middle third of the descending aorta. Orthogonal images show a crescent-shaped thrombus in the short-axis view. D. TEE - Distal third of the descending aorta. Orthogonal images of a wedge-shaped thrombus. Secondary thrombotic elements are in the opposite position to the initial one.

Figure 5 Shaggy aorta and thrombus. A 76-year-old man with a history of arterial hypertension, smoking, atrial flutter, and abdominal aortic aneurysm corrected by bilateral aorto-femoral bypass, referred intermittent claudication of the lower limbs. The patient was admitted on an outpatient basis for peripheral revascularization. The pre-surgical evaluation was complemented with transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) (see Figure 4) due to poor acoustic window in the transthoracic approach and a cardiac CT. A. CT angiogram - sagittal section of the aorta. Multiple atheromatous plaques, in tandem, along the entire course of the aortic arch and thoracoabdominal aorta (red arrows), predominantly in the supradiaphragmatic portion. B. Longitudinal reconstruction of the aorta. The cross-section shows plaques with a low attenuation coefficient (35 HU), irregular borders (lower central box), ulcerated and associated with images suggestive of thrombus (lower right box).

Figure 6 CENTRAL ILLUSTRATION. Shaggy aorta is characterized by severe atherosclerotic degeneration, resulting from a multifactorial pathophysiological process (with chronic inflammation, ischemia, aortic wall shear stress, and individual genetic susceptibility being fundamental to parietal remodeling and increased vulnerability). The clinical importance of this disease lies in the different clinical conditions to which it predisposes (aortic dissection, penetrating aortic ulcer, aneurysmal dilatation, and systemic embolization) and in its role as an independent and significant risk factor for operative mortality. Graphic created by the corresponding author.

The predisposition for the development of aneurysms and aortic dissection has a multifactorial basis involving chronic inflammation and ischemia of the aortic wall, which generates remodeling and increased susceptibility. The presence of severe atherosclerosis is associated with increased local expression of proteinases that contribute to tissue destruction, cell necrosis and apoptosis 20-23. On the other hand, the blood supply of the aorta is provided by simple diffusion (2/3 internal) and through the vasa vasorum (1/3 external), except for the infrarenal aorta, which lacks an independent vascular supply 24, therefore the presence of atheromas favors ischemia of the media with subsequent apoptosis of smooth muscle cells and weakening of the wall 25-27. This phenomenon, together with a simultaneous stressful stimulus, that exceeds the strength of the aortic wall, increases susceptibility to the development of aneurysms and/or aortic dissection.

Another syndrome associated with SA is central or peripheral, thrombi or cholesterol crystals embolism. Plaque stability is the result of the balance between mechanical resistance and the forces that affect the coating. Thus, unstable plaques will be characterized by the presence of a thin fibrous cap with few smooth muscle cells, covering a large lipid core with abundant foam cells and tissue factors 27-29. Fracture of the cap will expose the plaque tissue factor to blood clotting proteins, thus initiating the coagulation cascade and the formation of fibrin-rich thrombi, which embolize to the brain or peripheral organs. Likewise, the exposure of cholesterol crystals contained within the lipid core, can be embolized to the peripheral organs or extremities giving rise to SA syndrome (diffuse atheromatous embolization) 30-33.

Penetrating atherosclerotic ulcers (PAU) are caused by ulceration of the atherosclerotic plaque with extension into the media, producing a mushroom-shaped excrescence. They occur as unifocal or multifocal lesions in diffusely atherosclerotic aortas, particularly in the medial and distal portion of the descending aorta. Its timely diagnosis is essential, as large PAU (> 20 mm) with a depth greater than 10 mm are responsible for 2-7% of cases of acute aortic syndrome 5,34-37.

Diagnosis and multimodality

When evaluating aortic pathology, the method of choice will depend on the diagnostic suspicion, the patient’s comorbidities, and the availability of the method. These include transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Generally, more than one diagnostic tool will be used, emphasizing the importance of multimodality for proper diagnosis, and its choice will depend on the individualization of each case (Table 1 and Table 2) 36-47.

Table 1 Utility of cardiovascular images according to pathology

CT: computerized tomography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PAU: penetrating aortic ulcer; TEE: transesophageal echocardiography; TTE: transthoracic echocardiography.

*Except for the blind spot located at the junction of the distal ascending aorta and aortic arch.

Adapted from references 36 - 47.

Table 2 Choice of imaging studies according to pathology (consider patient characteristics, availability of the method, local experience, etc.)

| Gold Standard | Second choice | Third choice | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aortic Aneurysm | CT or MRI | TEE (if it shows good correlation with other methods previously) | - |

| Aortic Dissection | CT or MRI | - | - |

| Penetrating Aortic Ulcer | CT or MRI | TEE | - |

| Atherosclerosis / Aortic Thrombi | TEE | CT | MRI |

CT: computerized tomography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; TEE: transesophageal echocardiography; TTE: transthoracic echocardiography.

Adapted from references 36 - 47.

TTE allows visualization of the aortic root, sinotubular junction, ascending aorta (AAo), distal portion of the arch, and proximal portion of the descending aorta (DAo). However, this is limited by the acoustic window of each patient. On the other hand, TEE allows visualization, with higher spatial resolution, of the AAo, the arch, and the thoracic DAo, except a “blind spot” located at the junction of the AAo and the arch 48. The higher spatial resolution is due to the proximity of the esophageal transducer to the aorta and the higher wave frequency. For this reason, TEE is the imaging modality of choice to diagnose plaques in the thoracic aorta and to specify its morpho-structural characteristics 48 Thus, aortic plaque is defined as an irregular thickening of at least 2 mm in thickness with increased echogenicity with respect to the adjacent intimal surface. A complex aortic plaque, defined by a thickness ≥4 mm, ulcerated or with an associated mobile component, is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events and mortality 49.

CT allows visualization of the aorta in its entirety, detects calcified plaques, tortuosities, and aneurysms, and evaluates adjacent organs. The visualization of the lumen requires the use of contrast media, which can accurately define the aortic wall, perform precise measurements, identify and characterize aortic plaques, as well as their complications (endoluminal thrombi and the different forms of acute aortic syndrome) 48. Therefore, when acute aortic syndrome is suspected, it is considered the first diagnostic study, as long as it is contrasted and triggered. Its main limitations lie in the use of radiation and iodinated contrast.

MRI perfectly characterizes the composition of the aortic plaque (fibrous cap and lipid core) and identifies thrombi attached to the plaque 50. Its diagnostic capability is superior to TEE, particularly in AAo and arch, nonetheless, TEE has a better image quality in regards of the descending aorta 51. In addition, it allows assessment of cardiac and valvular function, information that is of interest in aortic pathology. Despite these advantages, its high cost, limited availability, longer acquisition time, and occasional use of contrast make it an ineligible method for diagnosis and follow-up.

Management

There is little evidence regarding the medical management of SA. Embolization is the main complication in severe atherosclerosis, leading to ischemic damage of target organs 30. This thromboembolic risk makes it necessary to consider the use of anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents. Initial studies reported benefits of warfarin over aspirin in secondary prevention, however these are scarce and not randomized 52. More studies are needed to determine the indication of these drugs. On the other hand, statins have been related to regression of plaque burden by magnetic resonance imaging 53, and in a retrospective study they reduced the stroke rate by up to 70%, being superior to antiplatelet drugs, which did not show a protective effect 54.

Although there is no clear indication for endovascular aortic treatment of the abdominal or thoracic aorta in patients with SA, we know that these patients are at increased risk for embolization and the development of acute and chronic aortic complications. Evidence suggests that ‘’prophylactic’’ endarterectomy of a severely atherosclerotic aorta for protruding atheroma as an adjunct to a cardiac procedure is not recommended because of the high incidence of intraoperative stroke 55. Nevertheless, patients with recurrent peripheral or visceral embolization and the presence of shaggy aorta with favorable anatomical features for endovascular reperfusion may undergo such treatment (Recommendation Class IIb, Level of Evidence C) 56. On the other hand, the management of complications associated with SA is beyond the scope of this review.

Conclusions

SA refers to severe atherosclerotic degeneration of the inner aortic surface, which is extremely friable and predisposes to various complications such as aneurysms, acute aortic syndromes, and peripheral embolization. The incidence and prevalence of SA in the world population are unknown. The fundamental bases for the development of SA and its complications are chronic inflammation, ischemia, aortic wall shear stress, and individual genetic susceptibility. On the other hand, multimodality imaging is essential for the timely and correct identification and characterization of aortic atherosclerotic plaques, especially complex ones, which are typical of SA. Each of these diagnostic tools has certain characteristics that favor or limit its usefulness. Finally, there is no consensus regarding the interventional or surgical management of SA, but its finding constitutes an important risk factor for operative and long-term mortality.