INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic had a high impact worldwide, reporting more than 775 million cases and 7 million deaths worldwide as of June 07, 2024 1. Multiple neurological manifestations associated with COVID-19 have been described in up to a third of patients; among them, the most frequently reported are fatigue, myalgia, taste impairment, smell disturbance, and headaches 2.

Autoimmune encephalitis has been reported to be temporarily associated with different previous viral infections, but to date the association with COVID-19 has been rarely described. The potential mechanism postulated by clinicians and researchers seems to be a molecular mimicry that may exist between viral epitopes and neuronal surface receptors and could lead to an immune response 3. These factors make it an entity in need of complex diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, even more so in developing countries where diagnostic support tools are scarce 4-6.

We present the case of a patient with autoimmune encephalitis associated with SARS CoV-2 infection, and the main findings of a review of pertinent literature.

CASE REPORT

A 47-year-old, self-sufficient woman, with a medical history of controlled chronic migraine and sporadic symptomatic treatment for episodes of moderate intensity, who also refers conciliation insomnia treated with clonazepam 0.5 mg daily, was seen in the ER of a local hospital. Her past surgical history included a hysterectomy in 2020 for abortive uterine myoma, with a negative pathology result for neoplasia. The patient had not received any dose of the COVID-19 vaccine.

She presented respiratory symptoms characterized by dyspnea, odynophagia, fever, and general malaise, due to a history of positive contact for COVID-19 (by her partner) the previous week; she went to the emergency room of a hospital for symptomatic respiratory patients, being diagnosed with mild COVID-19 by antigen test for SARS CoV-2 and hospitalized without oxygen requirement. During her hospitalization, she had isolated episodes of heteroaggressiveness, and a tendency to remain silent. Six days after admission and due to the steady course of respiratory symptoms, family members requested voluntary discharge to comply with measures of home isolation.

A week later, she returned to the emergency room presenting drowsiness, fever, and emission of incomprehensible sounds during interrogation. She was evaluated by medical personnel who raised a possible diagnosis of meningitis, performed a lumbar puncture with no abnormal findings, and began empiric antibiotic coverage with ceftriaxone 2 g/12 hours. Due to clinical deterioration of the level of consciousness to a state of torpor and an apparent right motor deficit, she was transferred to a national reference hospital for evaluation and management.

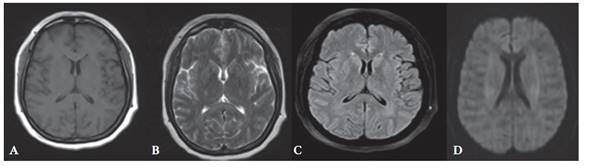

In the neurology service of this national hospital, findings such as soporousness, generalized hyperreflexia, slow reactive isochoric pupils were identified, but nor so signs of meningeal irritation. Her clinical course showed a self-limited generalized tonic-clonic seizure, for which a brain MRI was urgently performed without significant findings, except for a faint hypersignal at the left thalamic level (figure 1). A new lumbar puncture, resulted in a cerebrospinal fluid without alterations, proteinorrhachia or pleocytosis. Blood count and basic biochemistry serum tests reported no abnormalities. A prolonged electroencephalogram examination which did not register diffuse slowing in background activity nor associated epileptiform activity.

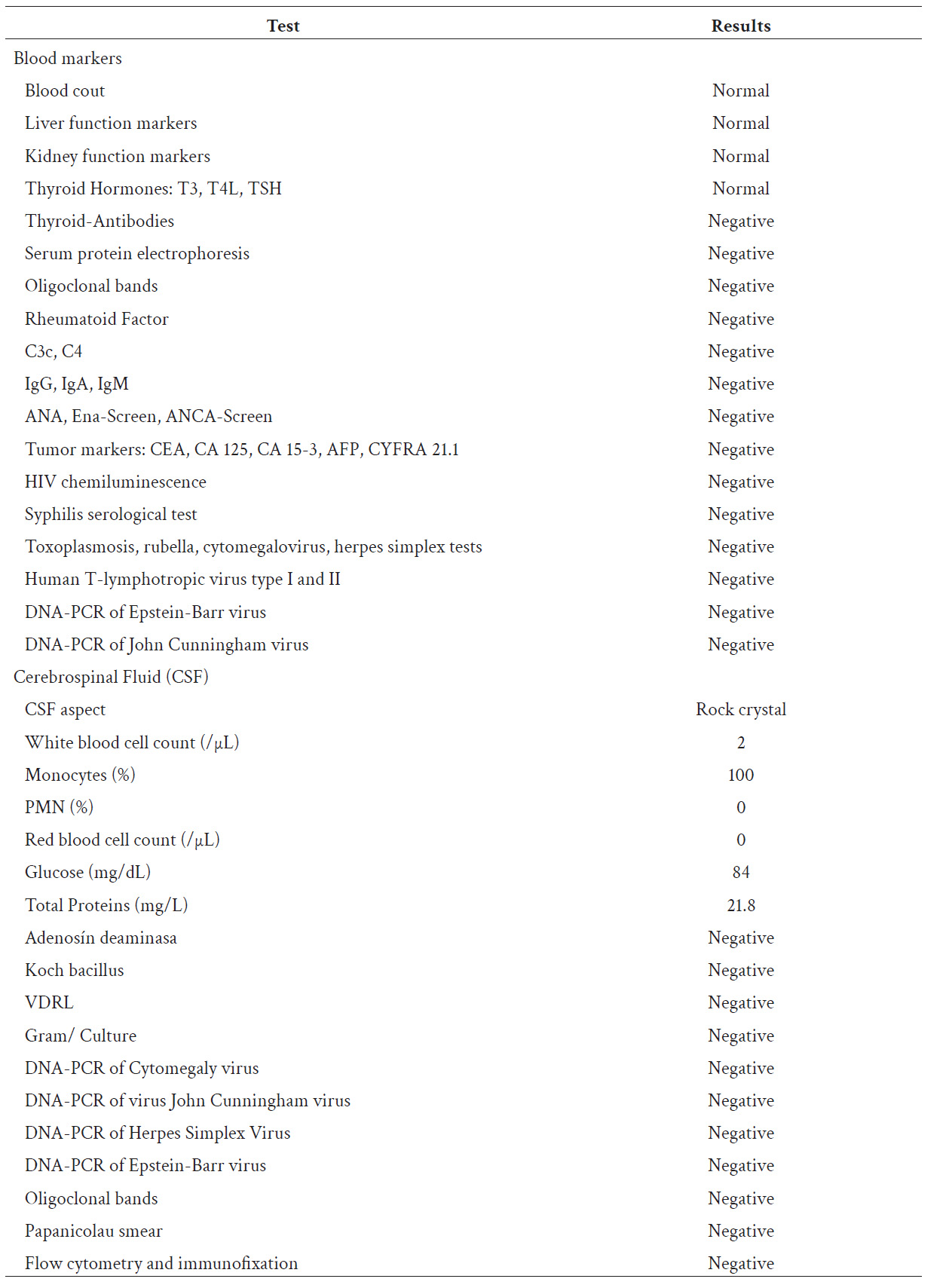

Due to clinical suspicion of acute non-infectious encephalitis of possible autoimmune etiology, a 5-day dual immunosuppressive treatment scheme with methylprednisolone 1 g and immunoglobulin 0.4 g/kg daily was started empirically, after taking serum and CSF samples whose tests were negative for systemic autoimmune, neoplastic, or associated infectious disease (Table 1). As part of the etiological study, a cervical, thoracic, abdominal and pelvic tomography with contrast was performed, which revealed a liver hemangioma but excluded the presence of solid malignant neoplasms.

Two weeks after the completion of the immunosuppressive treatment, the neurological examination revealed drowsiness, akinetic mutism, generalized hyperreflexia without new episodes of epileptic seizures.

Due to a lack of clear improvement in the patient, and pending the results of the autoimmune encephalitis panel, it was decided to start a second-line treatment with intravenous Cyclophosphamide at a dose of 750 mg/m2. During the two weeks that followed, the fluency of language improved, she began assisted ambulation with some gait apraxia, and showed constant emotional lability. The autoimmune encephalitis panel in CSF using the Indirect Immunofluorescence method in transfected cells, was negative (NMDA, CASPR2, AMPA 1, AMPA 2, GABA, LGI 1), and the treating team concluded that the patient met the criteria for possible autoimmune encephalitis, with the final diagnosis being probable seronegative autoimmune encephalitis associated with COVID-19. The patient was discharged with indication of monthly treatment with intravenous Cyclophosphamide until completing six months.

Five months after the diagnosis, following four months of the above treatment, the patient presented a notable improvement in her clinical condition, shows a fluent dialogue, is well-connected with the environment, has had no recurrent epileptic seizures (without anti-seizure treatment), but keeps manifestations of a severe residual neurocognitive disorder in brief cognitive tests (Montreal Cognitive assessment of 13 points).

DISCUSSION

The association of autoimmune encephalitis after viral infections and immunizations has been previously reported (7, 8). Since COVID-19 is a relatively new disease, more evidence of the true incidence of autoimmune encephalitis associated with this condition is needed. There are reports of prospective cohort studies in which a low incidence of encephalitis associated with COVID-19 (9, 10) (including one case in the Latin American population 11 has been reported, with fatal outcomes 12. In addition, cases of probable autoimmune etiology have been reported, highlighting those with positive serology for MOG, anti-NMDA and anti-GAD65 13-15.

In a systematic review of cases of autoimmune encephalitis associated with COVID-19 16, 18 articles were identified reporting 81 cases of patients, of which only 4 were classified as autoimmune encephalitis of unknown type, without specifically mentioning that they were seronegative 17-20 Comparing the clinical manifestations of the cases presented, it was similar to the case of our patient with predominance in neuropsychiatric clinical manifestations, language disorder, epileptic seizures and movement disorders. It was striking that, of the four cases, three were in older patients, and only one in a patient aged 18 years. In none of the cases it was necessary to use second-line therapy and no clinical follow-up was reported for them.

In another systematic review describing cases of autoimmune encephalitis temporally associated with COVID-19 or vaccination 21, there were 48 cases that met the criteria for possible autoimmune encephalitis, as previously reported; the median age was 60 years (IQR:46-66), which is high compared to the subgroup of patients diagnosed with definite autoimmune encephalitis. An altered mental status was the clinical picture most frequently reported, and regarding therapeutic approaches, a response to first-line immunotherapy was reported in 82.8% of cases.

Autoimmune encephalitis is a rare entity and over the years new antibodies responsible for these clinical conditions continue to be isolated, which suggests that some autoimmune encephalitis conditions that are primarily classified as seronegative are due to these antibodies not yet isolated’ this could have happened in the case of our patient where only the antibodies available in our environment (NMDA, CASPR2, AMPA 1, AMPA 2, GABA, LGI 1) were measured.

The different stages to attain the diagnostic conclusion in our patient were based on the established protocols 4. However, the lack of a confirmatory CSF test in our hospital and the need of a private external laboratory are logistic difficulties that make it difficult to arrive at early management decisions.

By consensus, if the patient has a clinical picture compatible with encephalitis and the main infectious, rheumatological and neoplastic etiologies are ruled out, a therapeutic diagnostic test must be performed until laboratory results are obtained 4. In cases where the magnetic resonance shows no alteration, a PET Scan study can be requested to demonstrate any metabolic change, to follow up therapeutic responses to immunotherapy, and to rule out an associated occult neoplasia 22. In our case, PET Scan could not be executed due to the patient's psychomotor agitation.

Our patient was treated following recommendations from different international sources (4, 23). In low- and middle-income countries and regions, diagnostic and therapeutic management must be adapted according to the availability and resolution capacity of hospitals 24. In this case, first-line treatment with methylprednisolone combined with immunoglobulin was initially chosen due to the clinical severity; as there was no evidence of improvement due to the persistence of akinetic mutism, it was decided, two weeks later, to start second line treatment with cyclophosphamide.

According to the reviewed literature, it is allowed to wait 3-4 weeks for a response to first-line treatment; however, therapeutic failure during the first month of immunosuppressive treatment is an indicator of poor functional prognosis 25. For this reason, we decided to escalate to a second-line treatment, which can be done either with Rituximab or Cyclophosphamide.

In our hospital, the use of Rituximab is not approved for adult patients with autoimmune encephalitis, so it was decided to start treatment with Cyclophosphamide, after ruling out any underlying infectious focus. It is noteworthy, according to the reviewed literature, that the highest proportion of cases of autoimmune encephalitis respond satisfactorily to first-line treatment 4,26, which was not our case: this can induce postulating that the association with COVID-19 could be a contributing factor for this type of response.

Thorough data on clinical relapses in patients with autoimmune encephalitis and COVID-19 have not been reported to date, but it could occur; therefore, we advocate a strict outpatient control, and recommend maintenance treatment for six months. to decrease the probability of this event happening.

CONCLUSIONS

The case of a seronegative encephalitis associated with COVID-19, probably of autoimmune etiology, due to the satisfactory response to second-line treatment with cyclophosphamide is presented and discussed. It is a diagnosis that must be considered when in presence of a suggestive clinical picture temporally related to COVID-19, after ruling out other secondary causes. More studies are needed to characterize seronegative autoimmune encephalitis associated with COVID-19, since our case was severe and resistant to first-line treatment despite timely introduction; these circumstances could indicate a greater probability of long-term sequelae.