Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Derecho PUCP

versión impresa ISSN 0251-3420

Derecho no.86 Lima ene./jun. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.18800/derechopucp.202101.002

Main Section

The Pacific Alliance and the CPTPP as alternatives to WTO dispute settlement

1Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile - Chile, natalia.gallardo.s@outlook.es

2Universidad de La Frontera - Chile, jaime.tijmes@ufrontera.cl

The World Trade Organization (WTO) dispute settlement system is currently in crisis because the WTO Appellate Body ceased effectively functioning in December 2019. As a consequence, the WTO Dispute Settlement Body is unable to adopt a panel report if a party to the dispute notifies its intention to appeal. In this context, this article analyzes what factors may influence the complaining parties’ decision on whether to recur to two regional trade agreements (RTA), namely the Pacific Alliance and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), as alternative fora to WTO dispute settlement. After a comparative analysis of dispute settlement rules in both RTAs and the WTO Dispute Settlement Understanding, we conclude that procedural and institutional factors will arguably be relevant for complaining parties that wish to select a dispute settlement forum.

Keywords: World Trade Organization (WTO); Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU); regional trade agreement (RTA; RTAs); Pacific Alliance; Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP; CPTPPA; TPP-11; TPP11; TPP; TPPA)

INTRODUCTION

The World Trade Organization (WTO) dispute settlement system is currently experiencing its most difficult moments since it entered into force in 1995. Set against the backdrop of what some authors argue is a breakdown of a rule-based system (Brewster, 2019; Patch, 2019), the United States has obstructed the appointment of new members for vacant seats to the WTO Appellate Body (AB) (Lehne, 2019; Bäumler, 2020) and, as a consequence, the AB has been unable to effectively function since December 2019.

If a party to a dispute notifies its intention to appeal, that appeal will remain pending and, as a result, the panel report shall not be considered for adoption by the WTO Dispute Settlement Body (DSB), according to article 16.4 WTO Understanding on the Rules and Procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes (commonly referred to as the Dispute Settlement Understanding, DSU). Thus, parties to the dispute will be left with a non-binding panel report whose compliance is impossible to request. Various ways out are possible. For instance, several WTO Members have agreed to an interim appeal arbitration arrangement . In addition, regional trade agreements (RTAs) may constitute an option for settling disputes bindingly.

In this article, our sample consists of two RTAs: The Pacific Alliance (PA) and the Comprehensive and the Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific3 Partnership (CPTPP). Both are latest generation RTAs that include deep substantive commitments and comprehensive dispute settlement systems. The PA is a Latin American economic integration project that started in 2011 and entered into force in 2016 (Toro-Fernández & Tijmes-Ihl, 2020). It has four members: Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru. The CPTPP is an economic integration project among several states from the Asia-Pacific region (Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam). As of November 2020, it has entered into force regarding some of its members. The CPTPP was created after the United States withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP); hence, the CPTPP is also sometimes unofficially referred to as TPP-11. The PA Additional Protocol (PA-AP) chapter 17 and TPP chapter 28 TPP (as incorporated into the CPTPP) each include a state-to-state dispute settlement system; so far, neither has been used in practice. Articles 17.4 PA-AP and 28.4 TPP (as incorporated into the CPTPP) allow complaining parties to choose a forum. While some RTAs also include dispute settlement procedures regarding investor-state dispute settlement (e.g. see Toro-Fernandez & Tijmes-Ihl, 2021), in this article we will only analyze the default state-to-state dispute settlement systems.

Before the USA abandoned the TPP, other authors had compared TPP and WTO dispute settlement, albeit in a less granular way and with a less legal focus than this article in order to explore if TPP dispute settlement would meet the interests of Asian members (Toohey, 2017). In our previous work, we concluded that previous dispute settlement patterns show that some PA and CPTPP parties may deviate from WTO dispute settlement (Gallardo-Salazar & Tijmes-Ihl, 2020).

Our research question is: what procedural and institutional legal rules on WTO, PA and CPTPP dispute settlement may induce complainants to choose forum? The importance of this research question is that, depending on those reasons, complaining parties may actually choose the PA or CPTPP dispute settlement system as alternative fora to WTO dispute settlement, especially in the context of the current AB crisis. It should be highlighted that the AB crisis constitutes the historical context that gives urgency to our analysis; however, we will not examine the AB crisis as such. In fact, our inquiry would arguably also make sense even if WTO dispute settlement were perfectly functional.

In this article, we will apply a positivist and comparative methodology including literal and systematic hermeneutic methods, thus interpreting and comparing the meaning of WTO, PA and CPTPP dispute settlement rules. From a voluntarist and formalist perspective, we will exclusively analyze treaty rules, and we will not consider other sources, such as customary international rules, judicial decisions, or state practice. In the past, other authors have undertaken similar normative comparisons in international economic law, for example Marceau (1997).

In section II, we will offer a brief introduction to RTA dispute settlement systems in the context of the AB crisis. In section III, we will compare the WTO, PA-AP and CPTPP dispute settlement systems in terms of their scope of application, the institutions that play a role in WTO, PA-AP and CPTPP dispute settlement, rules on parties to the disputes, and the procedural stages. In section IV, we will assess the strengths and weaknesses of these dispute settlement systems and evaluate the extent to which PA-AP and CPTPP dispute settlement may constitute alternatives to the crisis-plagued WTO dispute settlement. Section V concludes.

Article 1 CPTPP incorporated the TPP agreement by reference (although there are exceptions and article 2 suspended the application of some provisions), yet both are discrete treaties. Thus, we tried to devise an unequivocal, simple, and technically correct quotation method. On the one hand, allusions to TPP chapters and articles refer to the TPP as incorporated into the CPTPP. For example, references to article 28.1 TPP mean article 28.1 TPP as incorporated into the CPTPP. On the other hand, since the TPP currently exists only as incorporated into the CPTPP, we will refer to the CPTPP (not to the TPP) dispute settlement system.

For the sake of simplicity, in this article we will refer indistinctly to members or parties to the WTO, PA and CPTPP.

The WTO AB crisis and RTA dispute settlement systems

This section will briefly describe the current crisis affecting WTO dispute settlement, and the role that RTAs can play in this context.

The WTO dispute settlement system has been central to the multilateral trading system since its inception in 1995. According to article 3 DSU, this system was designed to deliver security and predictability to this multilateral framework, to provide its WTO Members with a tool to clarify the agreements’ provisions, and to preserve their rights and obligations.

Most observers agree that the WTO dispute settlement system as a whole “works remarkably well” (Porter, 2015). However, primarily the United States’ Obama and Trump administrations criticized the WTO as being unable to adapt to the new context of international trade (USTR, 2019), and as having lost its essence as a negotiation forum to become a “litigation-centered organization” (USTR, 2017). Therefore, the US has blocked consensus (pursuant to article 2.4 DSU) to appoint new AB members and has used it as leverage to force WTO Members to effectively address these issues and reform the dispute settlements system (Lehne, 2019, pp. 13-105). In December 2019, the AB effectively ceased to function.

Consequently, if a Member notifies its intention to appeal a panel report pursuant to article 16.4 DSU, the absence of a functional appeal stage makes it impossible for the WTO DSB to adopt the panel decision. Thus, there is an obvious incentive for losing parties to appeal. Moreover, systemic consequences may be wide-ranging. In the absence of a functioning dispute settlement system, WTO Members may increase unilateral actions (Brewster, 2019).

In this context, it is important that WTO Members can settle their disputes through a binding decision. The challenge is whether dispute settlement systems incorporated in RTA may perform this role among WTO Members that are parties to a certain RTA.

RTAs have increased in recent years in number, coverage, complexity, and political-economic importance (Stoll, 2017). As of January 2021, a total of 335 agreements in force have been notified to the WTO (World Trade Organization, 2021). These RTAs have expanded their substantive coverage, either by deepening matters already included in the WTO (so-called WTO+) or by adding matters not covered by the WTO (so-called WTO-extra). RTA dispute settlement systems have evolved from being politically oriented to become increasingly legalistic systems with highly sophisticated procedures (Chase, Yanovich, Crawford, & Ugaz, 2016). Many RTAs include rules regarding the choice of forum despite the several issues this raises, such as conflicting rulings and res iudicata, among others (Hillman, 2009, pp. 202-204). Typically, once the complaining party has selected a forum, it excludes other fora. The PA-AP and CPTPP are representative in these regards.

Comparing dispute settlement systems: the WTO, PA-AP and CPTPP

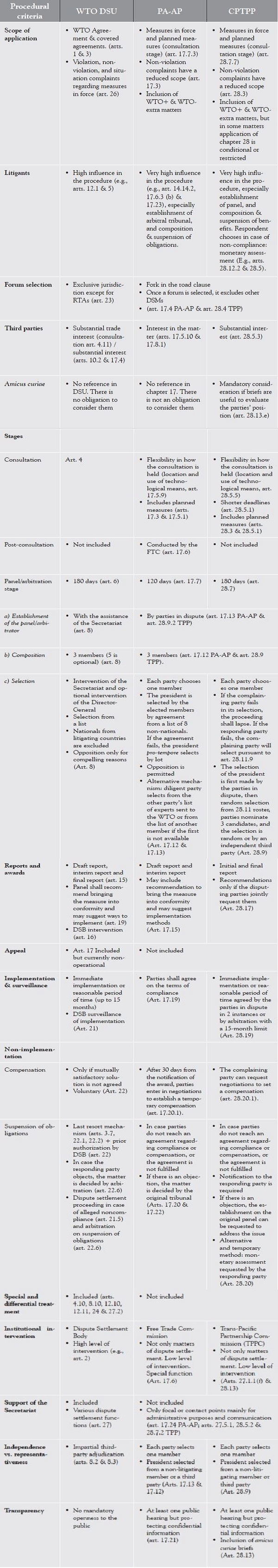

This chapter will offer a normative comparison of the rules regarding state-to-state dispute settlement in the WTO DSU, chapter 17 PA-AP and chapter 28 TPP. We will focus on their scope of application, their institutional setting, rules on parties to the dispute, and their main procedural stages. This comparison will highlight their main similarities and differences.

This will allow us, in the next chapter, to evaluate what reasons may be relevant for complaining parties to choose the WTO, PA or CPTPP for settling their disputes.

III.1. Scope of application

Pursuant to articles 1 and 3 DSU, the rules and procedures are applicable to consultations and disputes under the covered agreements listed in Appendix 1 DSU. According to article XXIII:1 GATT 1994 and article 26 DSU, parties may file a complaint if another party has nullified or impaired benefits or has impeded the attainment of an objective as the result of its failure to carry out its obligations under the covered agreements (violation complaints). Nullification, impairment, or impediment may also be the result of a measure that does not conflict with the covered agreements (non-violation complaints), or other situations (situation complaints).

Articles 17.3 PA-AP and 28.3 TPP state that these dispute settlement systems shall apply to prevent or solve disputes concerning the interpretation or application of the agreement, as well as to violation and non-violation complaints regarding measures in force or planned. However, the scope of non-violation complaints is reduced in both agreements on certain matters. According to annex 17.3 PA-AP, those matters are related to market access, rules of origin and procedures of origin, sanitary and phytosanitary measures, technical barriers to trade, public procurement, and cross-border trade in services. In the case of the CPTPP, dispute settlement regarding non-violation complaints includes chapters about national treatment and market access for goods, rules of origin and procedures of origin, textile and apparel goods, custom administration and trade facilitation, technical barriers to trade, cross-border trade in services and government procurement. An amendment to include the intellectual property chapter is pending until the WTO grants the right to initiate non-violation nullification or impairment complaints under its Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights.

Thus, the first main difference concerning the scope is that these RTAs include planned measures (but only for the consultations phase, pursuant to articles 17.7.3 PA-AP and 28.7.7 TPP). It should be noted that, even though WTO dispute settlement does not explicitly apply to planned measures, they may be framed as a situation complaint pursuant to article 26.2 DSU.

The second key refers to WTO+ and WTO-extra matters. The PA and the CPTPP have a wider scope than the WTO, and, therefore, offer a greater source of potential disputes. However, these RTAs frequently limit the scope for these disputes. For example, application of dispute settlement pursuant to chapter 28 TPP is conditional or restricted regarding sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures (article 7.18), technical barriers to trade (TBT) (article 8.4.2), and E-commerce (14.18). Other matters are entirely excluded from dispute settlement, such as anti-dumping (AD) and countervailing duties (CVD) (article 6.8.3), and competition (article 16.9).

III.2. Dispute settlement institutions

All three systems include organs that intervene in the dispute settlement process.

The WTO DSB is in charge specifically of administering dispute settlement rules and procedures pursuant to article 2 DSU. It establishes panels, adopts panel and AB reports, maintains surveillance of implementation of rulings and recommendations, and authorizes suspension of concessions and other obligations. Pursuant to article IV.3 WTO Agreement, the DSB is composed of representatives of all WTO Members, including those not related to a specific dispute; this reflects the multilateral nature of WTO dispute settlement.

The main PA and CPTPP institutions are the Free Trade Commission (FTC) and the Trans-Pacific Partnership Commission (TPPC), respectively. The PA FTC contributes to dispute settlement (article 16.2.1(c) PA-AP), for example assisting in a post-consultation phase (article 17.6 PA-AP). The TPPC may establish or amend rules of procedure and constitute and review the roster of panel chairs (articles 27.2.1(f) and (g), and 28.13 TPP).

The WTO Secretariat assists panels and WTO Members (especially developing countries), pursuant to article 27 DSU, while the WTO AB Secretariat provides support to the AB according to article 17.7 DSU. The secretariats play a crucial role because they provide specialized technical assistance in procedural matters and help in maintaining consistency in the reports (Davey, 2006). Neither the PA nor the CPTPP include secretariats. Instead, article 17.24 PA-AP requires parties to designate a permanent office for administrative support of panels, while articles 27.5.1 and 27.6 TPP incorporate contact points to facilitate communications among parties, and offices that provide administrative assistance to panels.

III.3. Parties, third parties and amicus curiae

In general, parties to disputes play an active role, for instance, regarding choice of forum and procedural decisions.

Article 23 DSU requires compulsory and exclusive jurisdiction for the WTO dispute settlement system, yet it also incorporates exceptions chiefly related to RTAs (Tijmes-Ihl, Article 23 DSU, forthcoming). In this context, PA-AP and CPTPP complaining parties may choose forum (articles 17.4 PA-AP and 28.4 TPP). In practice, RTA and WTO dispute settlement systems have dealt in parallel with the same material conflict (Pauwelyn, 2006, pp. 197-202) and future parallel disputes at the PA, CPTPP and WTO seem plausible. It is not clear if WTO panels may refuse to admit disputes that parties have previously taken to regional fora (Hillman, Dispute Settlement Mechanism, 2016, pp. 197-198).

Parties in all three systems may choose to follow the default procedural rules incorporated in each agreement or modify them (articles 17.14.2 PA-AP, 28.12.2 TPP and 12.1 DSU). Additionally, they may solve the dispute through alternative means -good offices, conciliation, and mediation- that are available even if a procedure has already been initiated (articles 17.6.3(b) and 17.23 PA-AP, 28.6 TPP and 5 DSU).

Developing and least-developed country status is relevant pursuant to articles 4.10, 8.10, 12.10, 12.11, 24 and 27.2 DSU, but not in PA-AP and CPTPP dispute settlement. This makes sense regarding the PA, as its members have similar development levels. In contrast, CPTPP membership is quite heterogeneous in this regard; hence, the lack of special and differential treatment is somewhat surprising. Therefore, at least in principle, WTO dispute settlement may be more beneficial for developing and least developed complainants.

All three dispute settlement systems allow third parties. Article 17.5.10 PA-AP requires that members have an interest in the matter in order to intervene as third parties during consultations, and the arbitral tribunal may even authorize extemporaneous requests (article 17.8.1). Article 28.5.3 TPP requires the interest to be substantial and that the third party merely explains its interest within certain deadlines. At the WTO, on the other hand, the complaining party chooses to submit its claim pursuant to article XXII:1 or article XXIII:1 GATT. According to article 4.11 DSU, third parties are allowed only in consultations held pursuant to article XXII:1 GATT. Thus, complainants may block third parties from consultations simply by filing the challenge under article XXIII:1 GATT (Pelc, 2017, pp. 206-208). Article 4.11 DSU requires that third parties have a substantial trade interest to join consultations but allows the defending party to assess the claim of that interest and reject the request; this makes sense, as third parties “sharply reduce the odds of early settlement” (Busch & Reinhardt, 2006, pp. 464-471). In contrast to consultations, involvement as a third party is a right in matters before a panel or the AB, as long as that member has a substantial interest and has followed certain procedural requirements (articles 10.2 and 17.4 DSU). Thus, third party participation at the WTO may depend on the complainant’s and the defendant’s conjunctive decisions and is subject to stricter requirements than in the PA-AP and CPTPP.

The DSU does not refer to amicus curiae briefs, but WTO panels and the AB have claimed they have a right to receive them even if some Members may oppose (Gao, 2006). The PA-AP refers to amicus curiae briefs in article 10.20.3 on investor-state dispute settlement, but not in in chapter 17. Thus, the legal framework is analogous to the DSU and PA arbitral tribunals may arguably adopt a similar interpretation than WTO panels and the AB. By contrast, article 28.13(e) TPP requires that panels consider amicus curiae briefs from non-governmental entities located in the territory of a disputing party. Accordingly, rules on this issue vary, but in practice these systems may converge.

III.4. Stages in the dispute settlement process

This section offers an overview of the main procedural phases in these dispute settlement systems.

III.4.1 Consultations

Consultations are confidential (articles 4.6 DSU, 17.5.8 PA-AP and 28.5.8 TPP) and start with a written request that shall include the identification of the measure and the legal basis for the complaint (articles 4.4 DSU, 17.5.1 PA-AP and 28.5.1 TPP). Deadlines for consultations are similar, yet slightly shorter in the CPTPP, and parties may agree to modify them (articles 4.3 DSU, 17.5.4 PA-AP and 28.5.2 TPP). Timeframes for consultations are shorter for urgent cases, such as when perishable goods are involved (articles 4.8 DSU, 17.5.5 PA-AP and 28.5.4 TPP).

As mentioned above, the scope of application of the PA-AP and the CPTPP includes planned measures. Consequently, parties to the PA and the CPTPP-unlike the WTO- may request consultations with respect to planned measures (articles 17.5.1 and 17.3 PA-AP, and 28.5.1 and 28.3 TPP). In contrast to the DSU, consultations may be held in person or by any technological means (articles 17.5.9 PA-AP and 28.5.5 TPP).

III.4.2 Post-consultation phase

PA-AP dispute settlement is unique in including a post-consultation phase. The FTC assists parties to settle their dispute, by means of convening technical advisers or working groups, recurring to alternative dispute settlement mechanisms, and even making recommendations (article 17.6 PA-AP).

III.4.3 Panel or arbitrator

The three dispute settlement systems include a panel or arbitration phase.

III.4.3.1 Establishment of a panel or arbitrator

A party that requested consultations may request the establishment of a panel (articles 6 DSU and 28.7 TPP) or arbitrator (article 17.7 PA-AP). The requesting party has to identify the measure or matter at issue and the legal basis of the complaint. In the WTO, it is the DSB who decides to establish (or not) the panel.

As already highlighted, PA-AP and CPTPP dispute settlement systems apply to planned measures, whereas the DSU does not. However, PA-AP arbitrators and CPTPP panels shall not be established to review proposed measures (articles PA-AP 17.7.3 and 28.7.7 TPP); thus, only consultations are available. By contrast, planned measures may arguably be framed as situation complaints pursuant to article 26.2 DSU, whereas the PA-AP and CPTPP do not allow situation complaints. Thus, at first glance it may seem that the PA-AP and CPTPP are more amenable to reviewing planned measures, but actually it is the WTO dispute settlement system.

Parties may agree on the terms of reference. If they fail to do so, standard terms of reference apply (articles 7 DSU, 17.11 PA-AP and 28.8 TPP).

III.4.3.2 Composition and selection of the panel or arbitration tribunal

The composition of panels or arbitration tribunal is similar, but selection processes differ widely, from the relatively simple (articles 8 DSU, 17.12 and 17.13 PA-AP) to the complex (article 28.9 TPP).

The WTO Secretariat maintains an indicative list of candidates (article 8 DSU). Panelists, as a general rule, should not be citizens of parties to the dispute. Parties to the dispute can only oppose that nomination for compelling reasons. In case of disagreement, the WTO Director General determines the composition of the panel in consultation with certain chairpersons. The selection of panelists should ensure the panel’s independence.

Article 17.13 PA-AP provides that each party to the dispute designates one arbitrator, who can be a national of that country. If a party fails to appoint an arbitrator, the other party may designate the missing arbitrator from the WTO indicative list of candidates. The parties to the dispute then select a president, who shall not be a national of any party nor permanently reside in a party. If they fail to choose a president, the PA pro tempore presidency will select by lot.

Blocking the panel selection process had been singled out as “a fundamental flaw” in dispute settlement pursuant to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), especially since the dispute about restrictions on sugar from Mexico (Lester, Manak, & Arpas, Access to Trade Justice: Fixing NAFTA's Flawed State-to-State Dispute Settlement Process, 2019, pp. 64-69). Chapter 28 TPP corrects some shortcomings of NAFTA dispute settlement, especially to avoid the deadlocks under the NAFTA process regarding the selection of panel members (Toohey, 2017, pp. 94, 99). Pursuant to article 28.9.2 TPP, each party to the dispute shall appoint one panelist within a certain timeframe. If the complaining party fails to do so, the proceeding lapses. If the responding party fails to appoint a panelist, the complaining party shall select a panelist from the responding party’s roster list. If the responding party has not established a roster list, the complaining party nominates three candidates and the panelist is randomly selected. Parties to the dispute appoint the panel chair who, as a general rule, shall not be a national of any of the disputing or third parties. If they do not agree on the chair, the two appointed panelists shall designate the chair from the roster list. If the two panelists do not agree on the chair, they shall appoint with the agreement of the parties to the dispute, or the parties shall appoint the chair by random selection from the roster list, or a party may request an independent third party to select the chair from the same roster. If the roster list has not been established, the parties to the dispute may nominate three candidates and the chair will be selected randomly or by an independent third party.

III.4.3.3. Rules of procedure

In the three systems, parties to the dispute may modify the rules of procedure (articles 12.1 DSU, 17.14.2 PA-AP and 28.12.2 TPP).

The DSU itself only schematically refers to rules of procedure and leaves the rest for the panel to decide. Rules should aim for flexible and efficient procedures, and high-quality reports, while providing parties sufficient time to prepare their submissions (article 12.2 and 12.4 DSU). There are specific rules of procedure for disputes that involve developing countries (article 12.10 and 12.11 DSU).

Articles 17.14 PA-AP and 28.13 TPP provide that the PA FTC and the TPPC shall establish rules of procedure. Those rules must include at least one public hearing and an initial and a rebuttal written submission. They must protect confidential information. PA-AP arbitrators’ deliberations are confidential (article 17.14.3 (e)) in contrast to the CPTPP. CPTPP rules of procedure shall allow amicus curiae briefs and specify the place where hearings shall be held (article 28.13 (e) and (h)) contrary to the PA-AP. Pursuant to articles 17.14.7 PA-AP and 28.12.4 TPP, the panel/arbitral tribunal shall decide by consensus but, if it is unable to reach consensus, it may decide by majority vote.

PA-AP arbitrators shall, as a general rule, issue their report after 120 days, and after 180 days (or six months) for CPTPP and DSU panels. Timeframes may be shortened or extended under certain circumstances or when the parties so agree (articles 17.15 PA-AP, 3.12, 12.8 and 12.9 DSU, 28.17.3 and 28.18.1 TPP). However, dispute settlement practice in the WTO shows that such timeframes are often not met.

III.4.3.4. Reports and awards

According to article 15 DSU, the panel first issues the descriptive sections of its draft report to the disputing parties, then it issues an interim report to the parties, and finally the panel issues a final report and circulates it to WTO Members. Pursuant to article 19 DSU, if the panel concludes that a measure is inconsistent with the covered agreements, it shall recommend the Member to bring the measure into conformity with the agreement and may suggest ways to implement the recommendations (but without adding or diminishing the rights and obligations provided in the covered agreements). According to article 16, this final report shall be considered for adoption by the DSB, unless it decides by consensus not to adopt it, or a party notifies its decision to appeal.

PA-AP arbitrators issue a draft award and a final award. The draft report shall determine if the defending party has complied with its obligations, or if the measure causes nullification or impairment, and it shall include any determination requested in the terms of reference (article 17.15 PA-AP). It may include a recommendation to bring the measure into conformity with the PA-AP, and it may suggest implementation methods (article 17.15.5). Mirroring the DSU, the PA-AP arbitrator cannot add or diminish the parties’ rights and obligations (article 17.15.6). Parties may comment on the report and the arbitrator may reconsider the draft report (article 17.15.7 and 17.15.8). After 30 days, the arbitrator notifies the final award to the disputing parties. This award is definitive, unappealable and binding (article 17.16).

CPTPP panels issue an initial and a final report. Pursuant to article 28.17.4 TPP, the initial report shall include findings of fact, the determination whether the measure is inconsistent with the obligations set in the agreement, if the defending party has not otherwise failed to carry out its obligations, or if the measure causes nullification or impairment. It shall also contain determinations requested in the terms of reference and the reasons for the findings and determinations. Unlike the DSU and the PA-AP, the CPTPP provides that only if disputing parties jointly request it, the panel may make recommendations. Similarly to the PA-AP, parties may comment on the initial report and the panel may modify it (article 28.17.7 and 28.17.8). Then the panel presents a final report to the disputing parties and releases it to the public (article 28.28.1).

III.4.4. Appeals

The appeal phase is arguably the most important difference between the DSU, and the PA-AP and the CPTPP. Few RTAs include an appeal mechanism, such as article 12 ASEAN Protocol on Enhanced Dispute Settlement Mechanism and chapter VII MERCOSUR Olivos Protocol, but the PA-AP and the CPTPP do not.

According to article 17.6 DSU, appeals are limited to issues of law covered in the panel report and legal interpretations developed by the panel. The AB may uphold, modify, or reverse the panel’s legal findings or conclusions (article 17.13). Like the panel, also the AB may suggest ways in which the defending party could implement the recommendations, but without adding or diminishing the rights and obligations provided in the covered agreements (article 19). AB reports must be adopted by the DSB, unless the DSB decides by consensus not to adopt it (article 17.14).

III.4.5 Implementation and surveillance

According to article 21 DSU, if immediate compliance with recommendations or rulings of the DSB is impracticable, the defending party shall have a reasonable period of time to do so. The defending party may propose a period of time and the DSB may approve it (article 21.3 (a) DSU); since the DSB decides by consensus (article 2.4 DSU), at first glance it seems that there is multilateral control of this issue. However, if the DSB does not approve, the disputing parties may mutually agree on a period of time (article 21.3 (b) DSU); thus, the DSU considers this a strictly bilateral issue. In the absence of agreement by the parties, an arbitrator shall determine the period of time (article 21.3 (c) DSU), thus multilateralizing the issue. If the disputing parties disagree as to if the defendant has implemented the panel and/or AB report, they may recur again to the panel and AB proceedings (article 21.5 DSU). Additionally, article 21.6 DSU provides for multilateral surveillance of the implementation of adopted recommendations and rulings, as any WTO Member may raise issues of implementation at the DSB and the defending party shall submit status reports.

Implementation proceedings pursuant to article 21.5 DSU may lead to an endless loop of dispute settlement, possibly preventing the complainant from moving the dispute to the next procedural steps. This is the so-called sequencing issue and was a matter of contention especially during the WTO’s early years. Nowadays, parties to a WTO dispute often reach an agreement regarding this issue.

Pursuant to article 17.19.1 PA-AP, the disputing parties shall agree on terms of compliance consistent with the determinations, conclusions, and recommendations of the arbitrator. There are no rules regarding a period of time to comply.

Article 28.19.3 TPP states that, in general, the defendant shall comply immediately. If that is not practicable, the responding party shall have a reasonable period of time to comply, unless the parties agree otherwise. If the disputing parties do not agree on that period of time, the chair may determine the period through arbitration (article 28.19.4 TPP).

Thus, procedural rules for determining a reasonable period of time to comply differ starkly. For instance, the PA-AP and CPTPP do not consider disputes about implementation, thus avoiding the sequencing issue. More importantly, the three systems include implementation procedures that depend on the parties to the dispute; however, the DSU adds a multilateral surveillance system, whereas the PA-AP and CPTPP leave surveillance as a bilateral issue. Multilateral name-and-shame monitoring undoubtedly strengthens the WTO dispute settlement system and arguably increases legitimacy, whereas the PA-AP and the CPTPP rely more strongly on countermeasures to achieve implementation.

III.4.6 Non-implementation, compensation, and suspension of benefits

According to articles 3.7, 22.1 and 22.2 DSU, parties should first strive for a mutually acceptable solution that is consistent with the covered agreements. The second-best choice is that the defendant fully implements the panel and/or AB reports, thus withdrawing the measures found to be inconsistent with the covered agreements. Third, the defendant may voluntarily grant temporary compensation pending the withdrawal of the measure. As a last resort, the complainant may request the DSB for a temporary authorization to suspend obligations to the defendant. The level of suspension shall be equivalent to the level of nullification or impairment (article 22.4 DSU). Article 22.3 DSU contains the principles and procedures that determine which obligations to suspend. If the disputing parties do not agree on the level of suspension, the DSB shall refer the matter to arbitration (article 22.6 DSU). The DSB shall continue to keep the issue under multilateral surveillance until the defendant brings the measure into conformity with the covered agreements (article 22.8 DSU).

Pursuant to article 17.20.1 PA-AP, the preferred solution is that the parties reach an agreement on implementing the arbitrator’s report, or on a mutually satisfactory solution. If they do not, parties may agree on a temporary mutually acceptable compensation. If that fails, or if the complainant considers that the defendant has not fulfilled the agreement regarding implementation, a solution, or compensation, the complainant may suspend obligations vis-a-vis the defendant (article 17.20.2 PA-AP). The level of suspension shall be equivalent to the level of nullification or impairment (article 17.20.2 PA-AP), identically to article 22.4 DSU. The principles and procedures to determine which obligations to suspend set forth in article 17.20.4 PA-AP are very similar to article 22.3 DSU. A main procedural difference is that the complainant may start to suspend obligations at any time (article 17.20.2 PA-AP) and the defendant may only then ask for an arbitrator to prospectively review the level of suspension or to prospectively review if the defendant has complied with the arbitrator’s report (article 17.22.1, 17.22.6 and 17.22.7 PA-AP); by contrast, WTO law grants the defendant the right to recur to dispute settlement procedures on compliance (article 21.5 DSU) and to arbitration on suspension of obligations (article 22.6 DSU) before the complainant may actually start suspending obligations. Thus, the PA-AP favors the complainant, who may suspend obligations that an arbitrator may ultimately overturn, whereas the DSU favors the defendant, who may recur to articles 21.5 and 22.6 DSU to effectively delay the complainant’s countermeasures.

Pursuant to article 28.20.1 TPP, after the reasonable period of time to comply has expired (or more improbably, if the defendant notifies that it will not comply with the panel report), the complainant may request the defendant to enter into negotiations with a view to developing mutually acceptable compensation. If they do not agree on compensation, or if the complainant considers that the respondent has failed to observe the terms of the agreement, the complainant may suspend benefits (article 28.20.2 TPP). The principles and procedures to determine what benefits to suspend (article 28.20.4 TPP) follow article 22.3 DSU more closely than article 17.20.4 PA-AP, for example regarding the importance of affected trade and the broader economic circumstances and consequences.

Similarly to the PA-AP, and in contrast to the DSU, the complainant may begin suspending benefits (article 28.20.3 and 28.20.6 TPP) and only then may the defendant request the panel to be reconvened (article 28.20.5 TPP). That panel may prospectively review the level of suspended benefits, it may assess if the complainant has followed the principles and procedures to determine what benefits to suspend, or it may decide if the suspension is unjustified because the defendant has already complied with the panel report. Thus, like the PA-AP, the CPTPP favors the complainant in this regard.

As in the DSU and the PA-AP, the level of suspension is bound by a criterion of equivalence, but in the CPTPP that benchmark is different: the level of suspended concessions shall have an effect equivalent to that of the non-conformity, or nullification or impairment (article 28.20, footnote 3, TPP). Thus, the emphasis is on effects, thus necessarily calling for some sort of econometric modeling. In practice, arbitrators pursuant to article 22.6 DSU have sometimes not relied on effects, but e.g., on the value of subsidies (Brazil - Aircraft (Art. 22.6), US - FSC (Art. 22.6), Canada - Aircraft (Art. 22.6)). However, they have repeatedly applied econometric models to estimate the effects of nullification or impairment and countermeasures in terms of foregone trade flows (such as EC - Bananas III (US) (Art. 22.6), EC - Hormones (US, Canada) (Art. 22.6)), lost net transfers (US - Copyright Act (Art. 25)), economic effects (US - Upland Cotton (Art. 22.6)), etc. Put differently, the CPTPP requires the panel to consider effects, thereby excluding some approaches followed by certain WTO arbitrators, but it does not specify what kind of effects the panel should consider, hence still leaving considerable leeway.

The complainant shall postpone countermeasures if the defendant offers to pay a monetary assessment (article 28.20.7 TPP). If the parties do not reach an agreement on the amount of the assessment, it shall be set at a level equal to 50% of the level of the benefits determined by the panel or, if the panel has not determined the level, 50% of the level that the complaining party proposed to suspend. The monetary assessment is understood as a second-best option, as it does not relieve the respondent from providing a plan to comply with the panel report (article 28.20.9 TPP). Monetary assessment is temporary and should, in principle, last a maximum of 12 months (article 28.20.10 and 28.20.11 TPP). If the defendant fails to fulfil its obligations regarding the monetary assessment, or if the monetary assessment period lapses while the defendant has not complied with the panel report, the complainant may apply countermeasures (article 28.20.12 TPP). By contrast, financial compensation has been discussed for quite some time in the WTO context (e.g. Sutherland, et al., 2004, p. 54; Bronckers & van den Broek, Financial Compensation in the WTO, 2005) and has on occasion been granted (O'Connor & Djordjevic, 2005), but amendments to the DSU have failed to materialize.

In summary, the PA-AP and CPTPP offer interesting innovations vis-a-vis the DSU that strengthen the position of the complainant, e.g., regarding immediate suspension of obligations and monetary assessment. By contrast, the WTO offers multilateral surveillance of the implementation of the panel/AB report and this, as mentioned in the previous section, arguably increases legitimacy and the name-and-shame effect.

III.4.7 Summary

The three systems are available to settle state-to-state disputes that arise from the application and interpretation of the respective agreements, of a breach of an obligation, or when a member nullifies or impairs benefits, or prevents the obtention of objectives. Unlike the WTO, the PA-AP and CPTPP cover both current and planned measures, although their review is only allowed at the consultation stage. The WTO dispute settlement system applies to all covered agreements (appendix 1 DSU), while the CPTPP in particular excludes certain subject matters. In this sense, the CPTPP on the one hand extends the scope by including projected measures, but on the other hand reduces it by excluding important matters that are normally the source of most disputes at the WTO, such as trade remedies, TBT and SPS. Thus, it seems that the CPTPP is more relevant for its members in terms of its substantive concessions than for incorporating a dispute settlement system.

These three systems incorporate a first stage of consultations between parties in order to obtain an agreed settlement to the dispute, and after that a review stage by an impartial panel or arbitrator. The PA-AP opts for arbitration, whereas the DSU and the CPTPP recur to panels; however, the difference is terminological and has no substantial effect on these procedures. Procedures for selecting panelists/arbitrators vary, the CPTPP procedure being the most complex. The three systems include similar terms of reference, which the parties can modify according to the type of analysis they expect the panel/arbitrator to perform. They share procedural rights for the parties, such as presenting briefs (initial and rebuttal), at least one hearing to present oral arguments, and the protection of confidential information. They also grant third parties the possibility to participate. The three systems consider at last an initial report on which the parties can comment, and a final report.

Regarding implementation, the three systems emphasize the importance of compliance with the ruling. Defendants may be granted a reasonable period of time to comply. In cases of non-compliance, the three systems allow for compensation as a temporary solution and, as a last alternative, to resort to suspension of obligations. They include similar principles for selecting the sector where the complainant may suspend obligations. In the WTO, if the defendant objects to the proposed countermeasures, an arbitration must be followed before the complainant may start suspending obligations. Irrespective of that arbitration, the DSB must authorize WTO countermeasures. By contrast, the PA-AP and the CPTPP allow the complainant to initiate suspension without a previous authorization, but subject to review by the panel/arbitrator. The CPTPP includes monetary assessment as an alternative to retaliation.

When comparing these three systems, the most significant differences refer to the multilateral nature of WTO dispute settlement as expressed in the DSB, and to the WTO appeal stage.

Other authors have concluded that the strength of RTA dispute settlement varies according to the agreement depth, the involvement of the United States, and power asymmetry between members (Allee & Elsig, 2016). Thus, we would have expected stark differences between the PA and CPTPP disputed settlement. However, while we have detected several differences, we are surprised that they are far weaker than expected.

Evaluating the PA-AP and the CPTPP as alternatives to WTO dispute settlement

In the previous section we compared the WTO, PA-AP and CPTPP state-to-state dispute settlement systems. In this section we will review some of the most important reasons why complaining parties may choose to settle a dispute at the PA or CPTPP regional forum, instead of resorting to the WTO multilateral forum.

We will consider two sets of criteria: procedural and institutional. Regarding the former, we will evaluate the following: the scope of application, the procedural stages, and, finally, compliance and the available remedies in case of non-compliance. From the institutional point of view, we will evaluate both RTA dispute settlement systems based on their structure, special and differential treatment, and transparency.

IV.1. Procedural perspective

IV.1.1 Scope of application

The scope of matters subject to dispute settlement is a central matter. We will focus on two issues: planned measures and WTO+ and WTO-extra topics. Regarding the first, the PA and the CPTPP expressly allow dispute settlement consultations regarding planned measures. These consultations are a formal stage that induces proactive regulatory cooperation when states create measures and, therefore, it decreases the probability of disputes once measures are in force. However, a PA or CPTPP panel/arbitrator shall not be established to review planned measures. By contrast, planned measures are not part of the scope of WTO dispute settlement system, arguably unless as a situation complaint under a broad interpretation of article 26 DSU. Consequently, on occasions it may be a sound procedural tactic for complainants to use the PA-AP or the CPTPP to hold consultations about planned measures; if those consultations are not satisfactory, the complainant may then turn to the WTO and submit a situation complaint.

Regarding matters where the parties to an RTA have made deeper concessions than at the WTO (WTO+) or have made concessions over matters that the WTO does not cover (WTO-extra), those RTAs obviously are the forum to settle disputes (Chase, Yanovich, Crawford, & Ugaz, 2016). The PA covers few WTO-extra concessions (most notably electronic commerce and financial services), whereas the CPTPP includes several (e.g., electronic commerce, financial services, competition policy, labor, environment, etc.). Thus, there is a strong argument in favor of the PA mostly regarding WTO+ concessions, but less so concerning WTO-extra concessions. By contrast, the CPTPP includes numerous WTO-extra concessions, but excludes certain subject matters from its dispute settlement system. For instance, the CPTPP does not apply chapter 28 dispute settlement to disputes regarding antidumping and competition, perhaps to avoid conflicts of competence in matters that are treated in very similar terms at the regional and multilateral level, or because CPTPP members expected to eventually include WTO-extra matters in the WTO (Stoll, 2017, pp. 15-16). Thus, we deduce that the main reason for creating the CPTPP was probably not to settle disputes, but rather to cooperatively deepen trade regulations in the context of a mega-regional agreement.

IV.1.2. Procedural stages

Regarding consultations, the PA-AP and the CPTPP include certain procedural innovations that are especially worth highlighting. First, parties may decide where and how consultations will take place. Second, these dispute settlement systems are open to holding consultations by any technological means: this decreases procedural costs, but also makes negotiations more difficult (Roberts & St. John, 2020). But overall, these flexibilities could be an incentive to prefer PA or CPTPP over WTO dispute settlement if disputing parties do not expect the dispute to go beyond the consultation stage, as has been the historical trend for most WTO disputes among PA members and some WTO disputes involving CPTPP members (Gallardo-Salazar & Tijmes-Ihl, 2020, pp. 653-655).

The PA includes arbitrators, unlike WTO and CPTPP panels. Some authors have argued that the reason for this is that PA members wanted to maintain the model included in bilateral agreements that they have signed with the United States (Álvarez Zárate & Beltrán Vargas, 2019); we disagree, because all those bilateral agreements included a panel system. However, the difference between PA arbitrators on the one hand, and WTO and CPTPP panels on the other, is only terminological.

One of the most important concerns is how to prevent parties from blocking the appointment of panelists or arbitrators (Lester & Manak, The Fundamental Flaw in the New NAFTA Deal, 2018). WTO rules have shown to be robust in this regard (in contrast to rules on selecting AB members). At least in theory, PA-AP and CPTPP rules seem quite robust too (in the same vein, Lester, Manak, & Arpas, Access to Trade Justice: Fixing NAFTA's Flawed State-to-State Dispute Settlement Process, 2019, pp. 70-72). It will be interesting to observe how much effort PA and CPTPP parties will invest in preparing lists of arbitrators or panelists, as it will reflect how much importance they ascribe to these dispute settlement systems and their future operation.

Even though WTO appeals are factually not available, they remain a right for the parties to the dispute. Thus, in cases where a party is not planning to comply with an adverse panel report, it may suspend the procedure indefinitely simply by appealing “into the void”. Thus, the complainant is left with a panel report that the DSB cannot adopt and that the defending party cannot be forced to comply with. In this context, defending parties can be forced to comply with PA-AP and CPTPP reports, and that is an incentive for complaining parties to resort to these regional fora instead of bringing their dispute to the WTO, especially when the complainant expects that the dispute would reach the WTO AB (Gallardo-Salazar & Tijmes-Ihl, 2020, pp. 655-656).

According to WTO dispute settlement patterns of PA and CPTPP members, the effects of the AB crisis vary for different parties. The five WTO disputes among PA members did not even finish the WTO panel stage and were settled by consultations or withdrawn. Consequently, if PA members expect to settle their future disputes following this pattern, the WTO AB crisis will arguably not influence the PA members’ choice of forum, as both the WTO and the PA offer a forum for dispute settlement through diplomatic means. By contrast, WTO dispute settlement patterns among CPTPP show a different picture. WTO disputes among certain CPTPP members have gone beyond the panel stage. For those CPTPP members, the AB crisis will arguably affect their choice of forum, as claimants will probably prefer the CPTPP over the WTO. However, the reduced scope of matters subject to CPTPP dispute settlement (in comparison to the WTO) means that members will not be able to effectively settle disputes regarding a number of matters either at the WTO or at the CPTPP (Gallardo-Salazar & Tijmes-Ihl, 2020, pp. 653-656).

IV.1.3.Compliance

Another important aspect is compliance. The DSU and the CPTPP include the possibility to grant the defendant a reasonable period of time to comply. By contrast, the PA-AP does not, making the dispute settlement process more expeditious, at least in theory.

Although there was some debate as to whether WTO rules allowed efficient breach (Bello, 1996; Jackson, 1997), by now the question seems settled that WTO members have a duty to comply with DSB decisions. Meanwhile, articles 17.20.1 and 17.20.4 PA-AP and 28.20.15 TPP univocally articulate a duty to comply with arbitrator/panel rulings. The effectiveness of suspending obligations to induce compliance has been discussed at large in the WTO context (Tijmes-Ihl, Jurisprudential developments on the purpose of WTO suspension of obligations, 2014, pp. 32-35), because it could go unnoticed against a respondent with a large market, or even be counterproductive for the claimant since it increases the import price in the domestic market regarding sectors that may not be related to the original dispute (Bronckers & Baetens, Reconsidering Financial Remedies in WTO Dispute Settlement, 2013, p. 282). To tackle these problems, the CPTPP allows the respondent to temporarily pay a monetary assessment to prevent the complainant from suspending obligations as a second-best option to restoring the balance of concessions through compliance (article 28.20.15 TPP stresses that it does not replace full implementation of the panel report). Monetary assessment is arguably an attractive alternative, as it provides a provisional remedy that does not, at least indirectly, affect the complainant’s interests or constitute only a symbolic victory. In addition, monetary assessment may be appealing for respondents that are unable to comply immediately with a panel ruling due, for instance, to political concerns or internal market pressures. However, it is not clear how it will be calculated (World Trade Organization, 2013, pp. 37, 50-51), and the consequences of its application are uncertain, especially considering the heterogeneity among member states in terms of economic development and power. By contrast, financial compensation is “generally considered not to be available in the WTO”, although “there have been disputes in the WTO that reportedly resulted in arrangements involving financial transfers between the parties,” namely US - Section 110(5) Copyright Act and US - Upland Cotton (World Trade Organization, 2013, p. 6 and footnote 9).

In summary, we conclude that at the procedural level both RTAs represent a viable alternative to WTO dispute settlement, especially in the current AB crisis.

IV.2 Institutional perspective

IV.2.1 Institutional structure

To begin with, we may ask if the WTO institutional structure related to dispute settlement, mostly the Secretariat, the DSB and the standing AB, may be a reason to prefer WTO over PA-AP and CPTPP dispute settlement. The main advantages of having a Secretariat relate to the fact that it “exerts enormous influence on the culture of an agreement” (Toohey, 2017, pp. 101-102), while the DSB institutionalizes multilateral oversight over disputes. By contrast, the main benefits of not having these organs involve faster and less bureaucratic processes (Hillman, Dispute Settlement Mechanism, 2016, p. 102). Also important are fewer administrative and infrastructure costs for disputing parties (Toohey, 2017, pp. 101-102). This last advantage is especially significant if members to the agreement anticipate that disputes will be infrequent, or if dispute settlement is probably not the main purpose of an RTA, as is the case regarding the AP and the CPTPP (Gallardo-Salazar & Tijmes-Ihl, 2020). In addition, lighter institutional structures may reflect a conscious decision for dispute settlement to reflect the power dynamics between disputing parties (particularly in case of non-compliance), and to keep disputes at a bilateral level without the intervention of other members. Thus, it is most likely that PA and CPTPP members did not intend to replicate the WTO dispute settlement institutions, but instead wanted to create an efficient regional system to deal with mainly bilateral conflicts.

In other words, were it not for the AB crisis, multilateral dispute settlement at the WTO would arguably be a better option regarding disputes that transcend the merely bilateral level. For instance, a measure that may affect states that are not members of the RTA, a dispute that may have strong political elements or where the complainant may want to create a multilateral precedent for future disputes, etc. (Davis, 2006; Busch M. , 2007). However, in most cases the current AB crisis will offset these multilateral advantages. By contrast, PA and CPTPP parties that are also parties to the WTO interim appeal arbitration arrangement mentioned before (namely Australia, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, New Zealand, Singapore, and Peru) may perhaps find WTO dispute settlement more attractive than the PA and CPTPP.

IV.2.2 Special and differential treatment

WTO dispute settlement includes rules on special and differential treatment (S&DT) for developing countries, whereas the PA-AP and CPTPP do not. Will this omission be significant enough for developing countries to prefer the WTO dispute settlement system? Perhaps not, as some authors have underscored that the WTO dispute settlement has been unable to offset the disadvantages that developing countries face, especially considering that many disputes are protracted and expensive (Walters, 2011). Be that as it may, it would be an interesting question for future research why the PA and the CPTPP do not include S&DT.

IV.2.3. Transparency

Openness and participation are also important issues. The three systems ensure confidentiality during consultations (articles 4.6 DSU, 17.5.8 PA-AP and 28.5.8 TPP). Regarding the litigation stage, some people have argued that the WTO dispute settlement system has an insufficient degree of openness towards the public (Charnovitz, 2004; Feeney, 2002), especially apropos hearings and amicus curiae briefs. WTO panel deliberations and AB proceedings are confidential (articles 14.1 and 17.10 DSU). Apart from that, there is no general rule on openness or secrecy of hearings and it has been up to the parties to WTO disputes, the panels and the AB to decide on a case-by-case basis. By contrast, the PA-AP and the CPTPP require at least one public hearing, although protecting confidential information. CPTPP procedural rules require panels to consider -under certain circumstances- requests to submit amicus curiae briefs (article 28.13(e) TPP); by contrast, the DSU and the PA-AP do not refer to this issue. Nevertheless, arguably only under exceptional circumstances would these rules regarding openness and amicus curiae briefs be a deciding factor when the complainant chooses forum, perhaps if the subject matter has a very high social impact or if the complainant wants to use openness and participation as a tactical tool against the defendant.

In summary, it seems plausible that complainants would often prefer WTO dispute settlement because of its stronger institutions, its multilateral nature and S&DT, whereas relatively low levels of openness and participation would most probably seldom counterbalance those strengths. In other words, under normal circumstances, it is likely that institutional incentives would have been strongly favorable for WTO dispute settlement over the PA-AP and CPTPP. In addition, we have to consider the peer effect of other members recurring to WTO dispute settlement, and the practical litigation experience already gained at the WTO, in contrast to the still untested PA and CPTPP dispute settlement systems. Yet again, the current AB crisis evidently offsets these institutional strengths.

IV.2.4. Summary

Are the PA-AP and CPTPP alternatives to WTO dispute settlement? From a procedural perspective, the scope of application of the PA-AP and CPTPP include consultations on planned measures, and they also include WTO+ and WTO extra matters (though the application of the CPTPP dispute settlement system is to some degree restricted). The PA-AP and the CPTPP offer complainants a definitive and binding solution - something that the WTO, under current circumstances, is not able to ensure. Avoiding a non-operational AB is especially important for CPTPP members, as a large part of WTO disputes between CPTPP members have reached the appeal stage (Gallardo-Salazar & Tijmes-Ihl, 2020, pp. 645-652). PA-AP and CPTPP procedures ensure representativeness as each disputing party appoints one panelist/arbitrator, they limit the possibilities of blocking appointments, and they guarantee the independence of the panel/arbitrator president. At the level of compliance, the CPTPP provides monetary assessments. Finally, both RTAs provide disputing parties with flexibility regarding logistical aspects, such as the place and technological means.

From an institutional perspective, the WTO dispute settlement system has its own strengths, such as the rules regarding S&DT. However, these features are arguably not very relevant for PA and CPTPP members, as WTO disputes among CPTPP parties have usually been among members with similar economic development levels (obviously, this also applies to the PA members). Another asset of WTO dispute settlement is the involvement of the DSB and the Secretariat. The PA-AP and the CPTPP guarantee public access to hearings and the CPTPP includes the obligation to consider amicus curiae briefs. These aspects are relevant especially in the context of disputes that involve socially contested issues.

Thus, PA and CPTPP members will likely recur to the WTO regarding disputes where rules on S&DT are important, that require the institutional support of the DSB or the Secretariat, or when the complainant wants to multilateralize the dispute or create a multilateral precedent.

Conclusions

WTO Members have successfully used the WTO dispute settlement system. However, the scenario changed radically in 2019 when the AB became unfunctional after the US succeeded in blocking appointments to the AB. In this context, our research question has been: what procedural and institutional legal rules on WTO, PA and CPTPP dispute settlement may induce complainants to choose forum?

After a normative comparison of the three dispute settlement systems, and after evaluating their procedural and institutional frameworks, we found that the PA and CPTPP include incentives that may encourage a complaining party to choose these regional fora to settle interstate disputes. However, it is essential to disaggregate this conclusion:

• The PA and CPTPP provide a great degree of legal certainty, as they offer complaining parties the certainty of binding decisions, whereas the WTO does not due to the current AB crisis.

• The PA and CPTPP have an extended scope of application to WTO+ and WTO-extra matters. In addition, consultations include planned measures. In this respect, two points must be highlighted. The first is that the WTO obviously only has competence in matters included in the WTO covered agreements. Second, the CPTPP -unlike the PA- restricts the application of state-to-state dispute settlement pursuant to Chapter 28, for instance regarding SPS, TBT and E-commerce, and excludes its application to anti-dumping, CVD, and competition. Consequently, the scope of CPTPP dispute settlement is procedurally restricted.

• The PA and particularly the CPTPP include mechanisms to prevent disputing parties from blocking the appointment of panelists or arbitrators.

• The PA and CPTPP are more flexible regarding how and where dispute settlement procedures should apply. They also allow using technological means during the consultation stage.

• Regarding the non-compliance stage, both RTAs have a relatively automatic system regarding suspension of concessions that does not depend on an institutional authorization. The CPTPP has the advantage of including monetary assessment as a temporary alternative to retaliation, thus giving the losing party greater flexibility.

After evaluating the WTO, PA and CPTPP dispute settlement systems, we may recapitulate that the WTO has some unique attributes. Its dispute settlement system includes tools to balance power differences among disputing parties, it enjoys the legitimacy of multilateralism, and it benefits from the technical support provided by the Secretariat. These features are especially valuable, for example in disputes that have strong political elements, or when the complainant wants to set a multilateral precedent. However, the current AB crisis (and, consequently, the prospect of not achieving a binding settlement to the dispute) overwhelmingly cancels out these institutional strengths. In the context of a weakened WTO dispute settlement system, the PA and CPTPP dispute settlement systems offer their own advantages for complaining parties, such as:

• A representative selection of panelists/arbitrators, as they may be nationals from the parties to the dispute. Simultaneously, the president shall be a national from a state that is not a party to the dispute, thus increasing independence.

• Consultation stages are confidential in the three systems. However, the panel stage at both RTAs is more transparent, for example regarding public hearings. The CPTPP also requires panels to consider amicus curiae briefs. These rules may arguably become especially relevant in cases regarding matters of high social interest.

In summary, while dispute settlement seems not to have been the most influential aspect when deciding to create the PA and the CPTPP, we conclude that institutional as well as procedural aspects may make it attractive for complaining parties to select the PA or the CPTPP to settle state-to-state disputes. This has become especially relevant in the context of the current WTO AB crisis.

REFERENCES

Allee, T., & Elsig, M. (2016). Why do some international institutions contain strong dispute settlement provisions? New evidence from preferential trade agreements. The Review of International Organizations, 11, 89-120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-015-9223-y [ Links ]

Álvarez Zárate, J., & Beltrán Vargas, D. (2019). The Pacific Alliance Dispute Settlement Mechanism: One More for the Heap. En P. Sauvé, R. Polanco Lazo y J. Álvarez Zárate (eds.), The Pacific Alliance in a World of Preferential Trade Agreements. Cham: Springer. http://doi-org-443.webvpn.fjmu.edu.cn/10.1007/978-3-319-78464-9_13 [ Links ]

Bäumler, J. (Febrero de 2020). The WTO’s Crisis: Between a Rock and a Hard Place (KFG Working Paper Series, núm. 42, Berlin Potsdam Research Group 'The International Rule of Law - Rise or Decline?'). http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3544022 [ Links ]

Bello, J. (1996). The WTO Dispute Settlement Understanding: Less is More. American Journal of International Law, 90(3), 416-418. https://doi.org/10.2307/2204065 [ Links ]

Brewster, R. (2019). WTO Dispute Settlement: Can We Go Back Again? AJIL Unbound, 113, 61-66. https://doi.org/10.1017/aju.2019.4 [ Links ]

Bronckers, M., & Baetens, F. (2013). Reconsidering Financial Remedies in WTO Dispute Settlement. Journal of International Economic Law, 16(2), 281-311. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiel/jgt014 [ Links ]

Bronckers, M., & van den Broek, N. (2005). Financial Compensation in the WTO: Improving the Remedies of WTO Dispute Settlement. Journal of International Economic Law, 8(1), 101-126. https://doi.org/10.1093/jielaw/jgi006 [ Links ]

Busch, M. (2007). Overlapping Institutions, Forum Shopping, and Dispute Settlement in International Trade. International Organization, 61(4), 735-761. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818307070257 [ Links ]

Busch, M. L., & Reinhardt, E. (2006). Three's a Crowd: Third Parties and WTO Dispute Settlement. World Politics, 58(3), 446-477. https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.2007.0000 [ Links ]

Charnovitz, S. (2004). Transparency and Participation in the World Trade Organization. Rutgers Law Review, 56, 927-959. [ Links ]

Chase, C., Yanovich, A., Crawford, J.-A., & Ugaz, P. (2016). Mapping of dispute settlement mechanisms in regional trade agreements - innovative or variations on a theme? En R. Acharya (ed.), Regional Trade Agreements and the Multilateral Trading System (pp. 608-702). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316676493 [ Links ]

Davey, W. (2006). Dispute Settlement in the WTO and RTAs. En L. Bartels y F. Ortino (eds.), Regional Trade Agreements and the WTO Legal System (pp. 343-357). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199206995.001.0001 [ Links ]

Davis, C. L. (2006). The politics of forum choice for trade disputes: Evidence from US trade policy. Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association. Filadelfia. [ Links ]

Feeney, S. (2002). The Dispute Settlement Understanding of the WTO Agreement: An Inadequate Mechanism for the Resolution of International Trade Disputes. Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, 2(1), 104-115. [ Links ]

Gallardo-Salazar, N., & Tijmes-Ihl, J. (2020). Dispute Settlement at the World Trade Organization, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, and the Pacific Alliance. Journal of International Dispute Settlement, 11(4), 638-658. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnlids/idaa021 [ Links ]

Gao, H. (2006). Amicus Curiae in WTO dispute settlement: Theory and practice. China Right Forum, 1, 51-57. [ Links ]

Hillman, J. (2009). Conflicts between Dispute Settlement Mechanisms in Regional Trade Agreements and the WTO-What Should the WTO do? Cornell International Law Journal, 42, 193-208. [ Links ]

Hillman, J. (2016). Dispute Settlement Mechanism. En C. Cimino-Isaacs y J. J. Schott (eds.), Trans-Pacific Partnership: An Assessment (p. 213-231). Washington, D. C.: Peterson Institute for International Economics. [ Links ]

Jackson, J. (1997). The WTO Dispute Settlement Understanding-Misunderstandings on the Nature of Legal Obligation. American Journal of International Law, 91(1), 60-64. https://doi.org/10.2307/2954140 [ Links ]

Lehne, J. (2019). Crisis at the WTO: Is the Blocking of Appointments to the WTO Appellate Body by the United States Legally Justified? Berlín: Carl Grossmann Verlag. [ Links ]

Lester, S., & Manak, I. (2 de octobre de 2018). The Fundamental Flaw in the New NAFTA Deal. Cato Institute. Recuperado de https://www.cato.org/publications/commentary/fundamental-flaw-new-nafta-deal [ Links ]

Lester, S., Manak, I., & Arpas, A. (2019). Access to Trade Justice: Fixing NAFTA's Flawed State-to-State Dispute Settlement Process. World Trade Review, 18(1), 63-79. https://doi.org/10.1017/S147474561800006X [ Links ]

Marceau, G. (1997). NAFTA and WTO Dispute Settlement Rules: A Thematic Comparison. Journal of World Trade, 31(2), 25-81. [ Links ]

O’Connor, B., & Djordjevic, M. (2005). Practical Aspects of Monetary Compensation: The US - Copyright Case. Journal of International Economic Law, 8(1), 127-142. https://doi.org/10.1093/jielaw/jgi007 [ Links ]

Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). (11 de diciembre de 2017). Opening Plenary Statement of USTR Robert Lighthizer at the WTO Ministerial Conference. Recuperado de https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/press-releases/2017/december/opening-plenary-statement-ustr [ Links ]

Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). (Marzo de 2019). 2019 Trade Policy Agenda and 2018 Annual Report. Recuperado de https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/reports-and-publications/2019/2019-trade-policy-agenda-and-2018 [ Links ]

Patch, C. (2019). A Unilateral President vs. A Multilateral Trade Organization: Ethical Implications In The Ongoing Trade War. The Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics, 32, 883-902. [ Links ]

Pauwelyn, J. (2006). Adding Sweeteners to Softwood Lumber: the WTO-NAFTA ‘Spaghetti Bowl’ is Cooking. Journal of International Economic Law, 9(1), 197-206. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiel/jgi060 [ Links ]

Pelc, K. (2017). Twenty Years of Third-Party Participation at the WTO: What Have We Learned? En M. Elsig, B. Hoekman y J. Pauwelyn (eds.), Assessing the World Trade Organization: Fit for Purpose? (pp. 203-222). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press . https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108147644.010 [ Links ]

Porter, R. (2015). The World Trade Organization at Twenty. Brown Journal of World Affairs, 21(2), 104-116. [ Links ]

Roberts, A., & St. John, T. (13 de October de 2020). UNCITRAL and ISDS Reform (Online): Can You Hear Me Now? EJIL:Talk! Blog of the European Journal of International Law. Recuperado de https://www.ejiltalk.org/uncitral-and-isds-reform-online-can-you-hear-me-now/ [ Links ]

Stoll, P.-T. (2017). Mega-Regionals: Challenges, Opportunities and Research Questions. En T. Rensmann (ed.), Mega-Regional Trade Agreements (pp. 3-24). Cham: Springer . https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56663-4_1 [ Links ]

Sutherland, P., Bhagwati, J., Botchwey, K., FitzGerald, N., Hamada, K., Jackson, J., Lafer, C., & de Montbrial, T. (2004). The Future of the WTO (Sutherland Report). Ginebra: World Trade Organization. [ Links ]

Tijmes-Ihl, J. (2014). Jurisprudential developments on the purpose of WTO suspension of obligations. World Trade Review, 13(1), 1-38. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474745613000177 [ Links ]

Toohey, L. (2017). Dispute Settlement in the TPP and the WTO: Which Way Will Asian TPP Members Turn? En J. Chaisse, H. Gao y C.-f. Lo (eds.), Paradigm Shift in International Economic Law Rule-Making: TPP as a New Model for Trade Agreements? (pp. 87-104). Singapur: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6731-0_6 [ Links ]

Toro-Fernández, J.-F., & Tijmes-Ihl, J. (2020). The Pacific Alliance and the Belt and Road Initiative. Asian Education and Development Studies [ahead of print]. https://doi.org/10.1108/AEDS-08-2019-0126 [ Links ]

Toro-Fernández, J.-F., & Tijmes-Ihl, J. (2021). Pacific Alliance, CPTPP and USMCA Investment Chapters: substantive convergence, procedural divergence. Derecho PUCP, 86. [ Links ]

Walters, J. (2011). Power in WTO Dispute Settlement. Journal of Third World Studies, 28(1), 169-183. [ Links ]

World Trade Organization. (2013). Mapping of Dispute Settlement Mechanisms in Regional Trade Agreements: Innovative or Variations on a Theme? WTO Working Papers (2013/17). https://doi.org/10.30875/93a8fc27-en [ Links ]

World Trade Organization. (2021). Regional trade agreements. Recuperado de https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/region_e/region_e.htm [ Links ]

REFERENCES

Acuerdo Amplio y Progresista de Asociación Transpacífico (CPTPP) (Sistema de Información sobre Comercio Exterior de la OEA, s.f.). Recuperado de http://www.sice.oas.org/TPD/TPP/TPP_s.ASP [ Links ]

Acuerdo Marco de la Alianza del Pacífico (Sistema de Información sobre Comercio Exterior de la OEA, s.f.). Recuperado de http://www.sice.oas.org/Trade/PAC_ALL/Framework_Agreement_Pacific_Alliance_s.pdf [ Links ]

Acuerdo de Asociación Transpacífico (TPP) (Sistema de Información sobre Comercio Exterior de la OEA, s.f.). Recuperado de http://www.sice.oas.org/TPD/TPP/Final_Texts/Spanish/TPP_Index_s.asp [ Links ]

Brasil - Aeronaves (art. 22.6): Brasil - Programa de financiación de las exportaciones para aeronaves. Recurso del Brasil al arbitraje previsto en el párrafo 6 del artículo 22 del ESD y el párrafo 11 del artículo 4 del Acuerdo SMC. Decisión de los árbitros. WT/DS46/ARB. 28 de agosto de 2000. [ Links ]

Canadá - Créditos y garantías para las aeronaves (art. 22.6): Canadá - créditos a la exportación y garantías de préstamos para las aeronaves regionales. Recurso del Canadá al arbitraje previsto en el párrafo 6 del artículo 22 del ESD y el párrafo 11 del artículo 4 del Acuerdo SMC. Decisión del árbitro. WT/DS222/ARB. 17 de febrero de 2003. [ Links ]

CE - Banano III (EE.UU.) (art. 22.6): Comunidades Europeas - Régimen para la importación, venta y distribución de bananos. Recurso de las Comunidades Europeas al arbitraje previsto en el párrafo 6 del artículo 22 del ESD. Decisión de los árbitros. WT/DS27/ARB/ECU. 24 de marzo de 2000. [ Links ]

CE - Hormonas (Estados Unidos, Canadá) (art. 22.6): Comunidades Europeas - Medidas que afectan a la carne y los productos cárnicos (hormonas). Reclamación inicial de los Estados Unidos. Recurso de las Comunidades Europeas al arbitraje previsto en el párrafo 6 del artículo 22 del ESD. Decisión de los árbitros. WT/DS26/ARB. 12 de julio de 1999. [ Links ]

Entendimiento Relativo a las Normas y Procedimientos por los que se Rige la Solución de diferencias (Organización Mundial del Comercio, s.f.). Recuperado de https://www.wto.org/spanish/docs_s/legal_s/28-dsu_s.htm [ Links ]

Estados Unidos - Artículo 110 (5) de la Ley de Derecho de Autor (art. 25.3): Estados Unidos - Artículo 110(5) de la Ley de Derecho de Autor de los Estados Unidos. Recurso al Arbitraje previsto en el artículo 25 del ESD. Laudo del Árbitro. WT/DS160/ARB25/1. 9 de noviembre de 2001. [ Links ]

Estados Unidos - Algodón americano (Upland) (art. 22.6): Estados Unidos - Subvenciones al algodón americano (Upland). Recurso por los Estados Unidos al arbitraje previsto en el párrafo 6 del artículo 22 del ESD y el párrafo 11 del artículo 4 del Acuerdo SMC. Decisión del Árbitro. WT/DS267/ARB/1. 31 de agosto de 2009. [ Links ]

Estados Unidos- EVE (art. 22.6): Estados Unidos - Trato fiscal aplicado a las "empresas de ventas en el extranjero". Recurso de los Estados Unidos al arbitraje previsto en el párrafo 6 del artículo 22 del ESD y el párrafo 11 del artículo 4 del Acuerdo SMC. Decisión del árbitro. WT/DS108/ARB. 30 de agosto de 2002. [ Links ]

Procedimiento arbitral multipartito de apelación provisional de conformidad con el artículo 25 del ESD, JOB/DSB/1/Add.12 (OMC, 30 de abril de 2020). [ Links ]

Protocolo Adicional al Acuerdo Marco de la Alianza del Pacífico (Sistema de Información sobre Comercio Exterior de la OEA, s.f.). Recuperado de http://www.sice.oas.org/Trade/PAC_ALL/Index_Pacific_Alliance_s.asp [ Links ]

Received: December 10, 2020; Accepted: March 24, 2021

texto en

texto en