Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Derecho PUCP

versión impresa ISSN 0251-3420

Derecho no.86 Lima ene./jun. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.18800/derechopucp.202101.005

Sección Principal

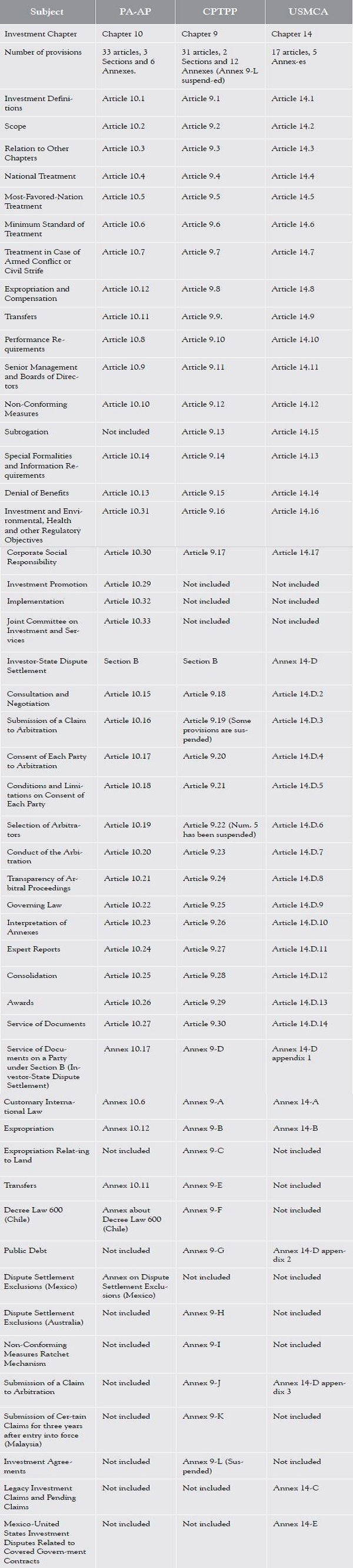

Pacific Alliance, CPTPP and USMCA Investment Chapters: Substantive Convergence, Procedural Divergence

1Universidad EAFIT - Colombia, jtorofer@eafit.edu.co

2Universidad de La Frontera - Chile, jaime.tijmes@ufrontera.cl

This article compares the investment chapters of the Additional Protocol to the Framework Agreement of the Pacific Alliance (PA-AP), the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). Our objective is to determine their degree of normative convergence. We conclude that these investment chapters include very similar substantive rules and principles on international investments in terms of definitions, the rules’ scope of application, treatment standards (national treatment and most favored nation treatment), absolute standards (international minimum standard of treatment, fair and equitable treatment, and full protection and security), investment protection rules (direct and indirect expropriation, compensation, and transfers), and performance requirements. We also conclude that these investment chapters differ, in some respects very strongly, regarding investor-State dispute settlement (ISDS). First, TPP and USMCA rules are often similar and frequently diverge from PA-AP rules. Second, party coverage and protection coverage diverge strongly between the USMCA vis-a-vis the PA-AP and CPTPP. Thus, as a consequence of substantive convergence and strong procedural divergence, we argue that complainants will most likely choose the forum between the PA-AP, CPTPP and USMCA according to procedural reasons.

Key words: Pacific Alliance (PA); Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP; CPTPPA; TPP-11; TPP11; TPP; TPPA); United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA); free trade agreement (FTA); international investment agreement; investor-State dispute settlement (ISDS)

Introduction

The Pacific Alliance (PA) is an area of deep economic integration (Rodríguez Aranda, 2014, p. 558) meant to achieve agreement, convergence, political dialogue and projection with the Asia-Pacific region2 among Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru (Toro-Fernández & Tijmes-Ihl, The Pacific Alliance and the Belt and Road Initiative, 2020; Toro-Fernandez & Tijmes-Ihl, forthcoming). Pursuant to the PA Framework Agreement signed in 2012, the objectives are to build a deep economic integration area, bolster economic growth, development and competitiveness, and become a platform for politic articulation with emphasis on the Asia-Pacific (article 3.1.a).

After the United States withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) project in 2017, the remaining parties (Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam) continued negotiations and signed the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) on 8 March 2018 (Organization of American States Foreign Trade Information System, n.d.; Toro-Fernandez & Tijmes-Ihl, forthcoming). The CPTPP is a comprehensive regional trade agreement for the Asia-Pacific region that seeks to promote regional economic integration and to accelerate regional trade liberalization and investment (CPTPP Preamble), among other goals. It incorporates the TPP provisions by reference (article 1 CPTPP), except for certain provisions that were suspended (article 2 CPTPP).

In 1994, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between Canada, Mexico and the United States entered into force. In 2018, NAFTA parties agreed to replace NAFTA with the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). The USMCA entered into force in 2020. Thus, Mexico is the only party to these three agreements.

Several authors have studied convergence between foreign investment rules and ISDS in multiple free trade agreements (FTAs), for example convergence between the PA and CPTPP (Toro-Fernández, Normative Convergence Between the Pacific Alliance and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Transpacific Partnership as a Way of Attracting Investments and Promoting Services Chaining with Asia-Pacific (LLM thesis), 2018, pp. 40-80), the PA and MERCOSUR (Herreros & García-Millán, 2017, pp. 24, 34-38; Novak & Namihas, 2015, pp. 190-196), or the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement between Canada and the European Union (CETA) and the Agreement between the European Union and Japan for an Economic Partnership (EUJEPA) (e.g. Furculita, 2020). Others have compared PA, CPTPP and World Trade Organization dispute settlement (Gallardo-Salazar & Tijmes-Ihl, Dispute Settlement at the World Trade Organization, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, and the Pacific Alliance, 2020; Gallardo-Salazar & Tijmes-Ihl, The Pacific Alliance and the CPTPP as alternatives to WTO dispute settlement, 2021).

Our research question is: to what degree are PA, CPTPP and USMCA rules on international investment (including rules on dispute settlement) convergent? We understand that rules are convergent if their legal meaning is similar and they admit a similar teleological interpretation (Schill S. , 2016, p. 25).

In this regard, this article’s purpose is to determine the degree of normative convergence between the investment chapters from the Additional Protocol to the Framework Agreement of the PA (PA-AP), the CPTPP and the USMCA. In order to do that, we will first compare these investment chapters (sections II to X). Through a comparative methodology, we will search for similarities and differences between rules in those investment chapters. Section XI offers an overview. In the concluding section, we will then evaluate to what extent these investment chapters are legally convergent.

To this end, we will apply a dogmatic legal theoretical framework so as to ascertain and interpret the ordinary meaning of legal rules. We will mostly apply literal and systematic interpretation methods. Our theoretical perspective is formalist, as we will only review formal sources of international law. In concrete terms, we will scrutinize only treaty texts. Since the regimes created by these treaties are quite new, there is still no case law, customary law, nor subsequent practice (pursuant to article 31.3(b) Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties) that we may analyze.

For this article we had to choose a working language. Spanish is the only authentic language for the PA-AP, and it is an authentic language for the CPTPP (article 7 CPTPP and article 30.8 TPP) and the USMCA (article 34.8 USMCA). As a consequence, we will compare all three treaty texts in Spanish, as it is the only common authentic language. However, in this article we will quote the English text.

A few words on quotations. Article 1 CPTPP incorporated the TPP agreement by reference (although there are exceptions and article 2 suspended the application of some provisions), yet both are discrete treaties. Thus, it is not easy to devise an unequivocal, simple and technically correct quotation method. On the one hand, in this text, references to TPP chapters and articles mention the TPP as incorporated into the CPTPP. For example, references to article 9.1 TPP mean article 9.1 TPP as incorporated into the CPTPP. By contrast, for example article 1 CPTPP refers to the CPTPP treaty as such. On the other hand, since the TPP currently exists only as incorporated into the CPTPP, we will refer to the CPTPP (not to the TPP) legal framework, its rules, and principles. In other words, in this article we will quote and analyze the CPTPP regime as it incorporates the TPP treaty text, and not the TPP regime itself. A certain degree of ambiguity may be inevitable, but we believe that with our quotation system attentive readers will easily and accurately discern what articles we are referring to.

A Comparison of Investment Chapters

PA-AP chapter 10 on investments aims at constituting a predictable normative framework for promoting and protecting investments among PA members. This is in line with the PA objective of progress towards free capital flows, as expressed in the PA Framework Agreement preamble. Likewise, the CPTPP investment chapter constitutes a predictable legal framework for investment with mutually advantageous rules for the countries pursuant to the TPP Agreement preamble. It enables countries to address future investment challenges and opportunities and to integrate into the Asia-Pacific region. The USMCA addresses future investment challenges and opportunities according to its preamble.

NAFTA triggered an extensive process of dissemination on foreign direct investment (FDI) protection standard rules. Thus, it should come as no surprise that the NAFTA investment chapter is the normative starting point for the investment chapters analyzed in this article. The PA-AP investment chapter bears some close similarities to the NAFTA investment chapter (Gutiérrez Haces, 2015, p. 33), just like other FTAs signed between PA members. Similarly, the CPTPP investment chapter is based on the NAFTA model. This arguably reflects US interests during TPP negotiations (Alvarez, 2016, pp. 503-507; Polanco Lazo, 2015, p. 179). Lastly, the USMCA answers concerns raised during the application of NAFTA.

In the following chapters we will analyze these investment chapters in terms of their convergence. Concretely, we will examine rules related to definitions, scope of application, treatment standards, absolute standards, investment protection rules, performance requirements, investor-State dispute settlement (ISDS), and additional rules. We will sometimes also compare these rules with other international agreements, most notably NAFTA and the US Model bilateral investment treaty (BIT) 2012.

Definitions

Definitions included in PA, CPTPP and USMCA investment chapters are very similar. They set a framework for understanding and interpreting the terms included in the respective investment chapter. The defined terms are commonly used in international investment law. These definitions must be understood for the purposes of the respective investment chapter (articles 10.1 PA-AP, 9.1 TPP and 14.1 USMCA) in contrast to general definitions that are generally valid for the respective agreement (articles 2.1 PA-AP, 1.3 TPP and 1.5 USMCA). This confirms that these investment chapters are self-contained (Zegarra Rodríguez, 2015, pp. 204, 210) and their rules, definitions and principles cannot be applied to other chapters of the same agreement.

III.1. Investment

“Investment” is a rather controversial term for academia and international arbitration (Manciaux, 2008, p. 804), as its meaning is unclear, broad (Amarasinha & Kokott, 2008, p. 138), and sometimes vague (Manciaux, 2008, p. 802). It is important to bear in mind that not even the Washington Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes Between States and Nationals of other States provides precise and clear provisions on the meaning of the term “investment”. This term is used indistinctively in article 25 of the Convention, when referring to the jurisdiction of the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), which has led, through disputes over the issue of jurisdiction, to its jurisprudential development in trying to find a more precise meaning (Manciaux, 2008, p. 804). Some scholars argue that the absence of a definition for the notion of investment in the Washington Convention is "the result of choice" (Manciaux, 2008, p. 804). Not providing a specific definition for the term could also be desirable, as it makes the concept of investment more flexible and functional (Manciaux, 2008, p. 805). However, we disagree on the desirability of lacking a definition, as it may not only generate flexibility, but also ambiguity. States and investors will not understand its notion and scope, nor other concepts founded on or associated with "investment".

Articles 10.1 PA-AP, 9.1 TPP and 14.1 USMCA define “investment” as “every asset that an investor owns” and contemplate several types of asset-based investments. This follows the 2004 and 2012 US Model BIT (Nottage, 2016, pp. 331, 346). Thus, they explicitly depart from article 1139 NAFTA, as its definition was primordially based on “enterprise” (UNCTAD, 2004, p. 90).

Similarly, it’s interesting how these agreements restrict the definition to “the characteristics of an investment” understood as “the commitment of capital or other resources, the expectation of gain or profit, or the assumption of risk”. Such characteristics have been jurisprudentially developed, particularly in Salini v. Morocco.3 Later tribunals referred to the characteristics an investment should have as the “Salini Test”: duration, profits and returns, risks, a contribution to the economic development of the host-State, and substantive contribution (Manciaux, 2008, pp. 801-802, 815, 823-824). We believe these PA, CPTPP and USMCA rules successfully restrict investments to cases where the investor has made a real contribution of capital, obtained profit and assumed risk. These rules protect States against investors who submit frivolous claims.

The term “investment” also includes an extensive list (also used in the 2004 and 2012 US Model BITs) of forms an investment may adopt, such as an enterprise, shares, stock and other forms of equity participation in an enterprise, bonds, debentures, other debt instruments, intellectual property rights, licenses, authorizations, permits and similar rights, turnkey, construction, management, production, concession, revenue-sharing and other similar contracts, and other tangible or intangible, movable or immovable property, and related property rights, such as leases, mortgages, liens and pledges. This list includes investment forms not included in NAFTA such as intellectual property rights, licenses, authorizations or permits, rights related to property or financial products such as futures, options and other derivatives. Thus, these agreements include assets and transactions where investors may acquire brand licenses, patents or industrial designs not previously considered a form of investment.

A substantial difference is that the PA excludes debt instruments issued by the State parties in the Agreement and/or by their State enterprises (sovereign bonds) as a form of investment. The CPTPP and the USMCA do not exclude such debt instruments, which means an investor could possibly invest in these types of public debt instruments. This needs to be considered when thinking of a unified investment regime for these agreements.

III.2. Investor

The PA, CPTPP and USMCA also define "investor". They exclusively refer to "investor of a party" and "investor of a non-party". Thus, neither treaty uses the term "foreign investor". Hence, an investor means an enterprise of a party that attempts to make, is making, or has made an investment in the territory of another State party. On the other hand, "investor of a non-party" means, with respect to a party, an investor that attempts to make, is making, or has made an investment in the territory of that party, that is not an investor of a State party. The purpose of this distinction is to determine who benefits from the treaty, and it sets a limit for those considered non-investors.

Australia, Canada, Singapore and New Zealand are CPTPP members and they are currently negotiating to become PA associate States. This would grant them the benefits of PA rules for investors of a party, laying the foundations for an environment that attracts investments in the Asia-Pacific region.

III.3. Covered Investment

The term "covered investment" is almost identical in these three regimes. It means the investment made in the territory of a State party to the agreement, by an investor of another party as of the date of entry into force of the agreement or established, acquired, or expanded thereafter. This concept is decisive in preventing future investor-State disputes, and especially in finding the time in which the investment was made in the territory of another State party to the agreement.

Two terms related to the concept of “covered investment” in the TPP were suspended in the CPTPP. They are “investment agreement” and “investment authorization” and they were included in the 2012 US Model BIT. Almost certainly these terms reflected US interests and the remaining CPTPP parties decided to suspend them after the United States withdrew from the TPP. By contrast, the PA-AP and the USMCA do not include these concepts, as additional charges are imposed to investors and parties in terms of signing written agreements containing rights and obligations on covered investments, which falls into the category of a performance requirement. It also becomes an obstacle for investments, as a foreign investment authority (which does not exist in all countries) is required to approve such covered investment within that territory. In this sense, we deem it beneficial for CPTPP countries to have agreed upon suspending those provisions.

III.4. Other definitions

Finally, the respective articles on definitions includes other terms, mostly relating to international arbitration, such as "claimant", "respondent", "disputing party", "non-disputing party", references to the ICSID Convention, ICSID Additional Facility Rules, and United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) Arbitration Rules. These terms are included in these three regimes; however, for example, London Court of International Arbitration Rules and International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) Arbitration Rules are only included in the TPP investment chapter.

These terms serve as the framework for initiating arbitration procedures, as contemplated in section B of the investment chapters. Investors and State parties of these agreements can use either arbitration system. This represents a significant progress in terms of an eventual common regime for these agreements.

Scope of application

Articles 10.2 PA-AP, 9.2 TPP and 14.2 USMCA refer to the scope, defining how, to what, and to whom the respective investment chapter may apply (similarly to article 1101 NAFTA and article 2 US Model BIT 2012). In concrete terms, these rules refer to measures adopted or maintained by State parties in relation to investors, covered investments, performance requirements, and health and environmental measures as well as other regulatory objectives. It should be highlighted that article 14.2.4 USMCA refers to annexes 14-D and 14-E, restricting the application of the investment chapter to investment disputes between the United States and Mexico, thus excluding Canada (except for legacy investment claims and pending claims pursuant to annex 14-C). Simultaneously, annex 14-E expands the scope of application to contracts, something NAFTA did not do.

TPP and USMCA obligations of the State parties apply to measures adopted or maintained by their central, regional or local governments, or by any bodies representing a government authority (articles 9.2.2 TPP and 14.2.2 USMCA). By contrast, article 10.2.4 PA-AP refers to delegated authority, such as the authority to expropriate, grant licenses, approve commercial transactions or impose quotas, fees or other charges.

These investment chapters do not apply to transnational services (articles 10.2.2 PA-AP, 9.3.2 TPP and 14.3.3 USMCA) nor measures related to financial institutions (articles 10.2.3 (a) PA-AP, 9.3.3 TPP and 14.3.2 USMCA). In this regard, the TPP and the USMCA are almost identical, while the PA-AP is not.

These investment chapters do not apply to acts or situations that took place or ceased to exist before the agreement entered into force (articles 10.2.3(b) PA-AP, 9.2.3 TPP and 14.2.3 USMCA).

Treatment Standards

Non-discrimination principles internationally referred to as national treatment (NT) and most favored nation (MFN) treatment are perhaps the most important guiding principles in trade and investment treaties (Herreros & García-Millán, 2017, p. 26; see also Chaisse, 2012, p. 149; Navarro, 2016, p. 5; Polanco Lazo, 2015, p. 180). The analyzed investment chapters include these principles in articles 10.4 and 10.5 PA-AP, 9.4 and 9.5 TPP and 14.4 and 14.5 USMCA.

NT and MFN principles are part of the minimum protection standards in international investment law, and that makes them substantive rights for foreign investors (Schill S. , 2016, pp. 26-27). These relate to standards usually found in free market economies as they "aim to ensure an even ground for the economic activity of national and foreign economic actors as a prerequisite for competition" (Schill S. , 2016, p. 66).

These principles tend to “multilateralize” the benefits that an investment-receiving State grants to local and foreign investors. Therefore, they "balance the relations between the receiving State and other States and push the international investment protection system towards multilateralism" (Schill S. , 2016, pp. 60-61). Thus, similarly structured NT and MFN principles help to multilateralize rules related to investments, ultimately supporting normative convergence in the Asia-Pacific region.

V.1. National Treatment (NT)

These agreements define NT almost identically as the obligation of each State party to the agreement to accord investments and covered investments treatment no less favorable than that which it accords, in like circumstances, to its own investors or to investments in the territory of their own investors (articles 10.4.1 PA-AP, 9.4.1 TPP and 14.4.1 USMCA).

This obligation covers every investment stage, from its establishment, acquisition, expansion, management, conduct, and operation, to its sale or other disposition. The extension from the pre-establishment to the post-establishment stage (Herreros & García-Millán, 2017, p. 26; Nottage, 2016, p. 323) is similar to that of articles 1102 NAFTA and 3 US Model BIT 2012, but not identical, as NAFTA prohibited States parties from imposing on an investor from another State the requirement of having a minimum level of shareholding in a company established in its territory and that of requiring an investor of another State party to sell or dispose of an investment in the territory of a party by virtue of its nationality.

Articles 9.4.3 TPP and 14.4.3 USMCA regulate NT regarding non-central government. The PA-AP does not include an analogous rule.

The TPP and USMCA clarify that whether NT or MFN treatment is granted in “like circumstances” “depends on the totality of the circumstances, including whether the relevant treatment distinguishes between investors or investments on the basis of legitimate public welfare objectives” (footnote 14 to chapter 9 TPP, articles 14.4 and 15.4 USMCA). The PA-AP does not include a similar disposition.

V.2. Most Favored Nation (MFN) Treatment

The MFN principle is enshrined in articles 20.5 PA-AP, 9.5 TPP and 14.5 USMCA. Parties to these agreements shall accord investors and covered investments a treatment no less favorable than that which they accord, in like circumstances, to investors and investments of any non-State party to the Agreement (articles 10.5.1 and 10.5.2 PA-AP, 9.5.1 and 9.5.2 TPP, 14.5.1 and 14.5.2 USMCA). Benefits have to be accorded from the pre-establishment until the post-establishment phase (Nottage, 2016, p. 318).

Pursuant to footnote 6 to chapter 10 PA-AP and article 9.5.3 TPP, MFN treatment does not encompass international dispute resolution procedures or mechanisms. The USMCA does not include an analogous rule.

Article 14.5.3 USMCA refers to NT regarding non-central government, analogous to article 14.4.3. The PA-AP and the TPP do not include a similar rule.

Footnote 14 to chapter 9 TPP and article 14.5.4 USMCA clarify the meaning of “like circumstances”, as mentioned in the section on NT. The PA-AP does not.

Absolute Standards

The three agreements include a minimum standard of treatment, as usual in investment chapters of FTAs and international investment agreements. It includes principles of fair and equitable treatment and full protection and security. They correspond to protection standards in accordance with international investment law (Chaisse, 2012, p. 149; Polanco Lazo, 2015, p. 180).

VI.1. International Minimum Standard of Treatment

Each State party to the agreement shall accord to covered investments in its territory a treatment in accordance with applicable customary law, including fair and equitable treatment, and full protection and security (articles 10.6.1 PA-AP, 9.6.1 TPP and 14.6.1 USMCA). Annex 10.6 PA-AP, annex 9-A TPP and annex 14-A USMCA almost identically express that customary international law results from a general and consistent practice of States that they follow from a sense of legal obligation.

These annexes, however, include different definitions of "customary international law minimum standard of treatment of aliens”: while annex 10.6 PA-AP refers to “economic rights of aliens”, annex 9-A TPP and annex 14-A USMCA refer to “investments of aliens”. This substantial difference may lead to different protections of assets. Investment protection pursuant to the PA-AP may include any economic right accorded to a foreigner, while according to the CPTPP and the USMCA it would arguably be restricted to investments. Hence, the CPTPP and the USMCA would arguably not protect an investor’s economic interest that is not yet classified as "investment", in contrast to the PA. On the other hand, the broadness of the term "economic rights" could be problematic for PA parties, as it may lead to claims by investors considering the protection of the minimum level of treatment for any economic right, even if it does not meet the definition of investment pursuant to the PA-AP.

VI.2. Fair and Equitable Treatment

“Fair and equitable treatment” is enshrined in identical terms in articles 10.6.2(a) PA-AP and 9.6.2(a) TPP, and with minor differences in article 14.6.2(a) USMCA. It includes the obligation not to deny justice in criminal, civil or administrative adjudicatory proceedings in accordance with the principle of due process embodied in the main legal systems of the world.

This principle is one of the absolute treatment standards found in international agreements on the promotion and protection of foreign investment (UNCTAD, 2004, p. 73). It has been criticized because its definition and scope are not precise (Dolzer & Schreuer, 2012, p. 133; Herreros & García-Millán, 2017, p. 20). That same criticism is valid regarding the PA-AP, CPTPP and USMCA, as they do not clearly define fair and equitable treatment, but only refer to it in an abstract and broad sense.

Because of this imprecision, tribunals in investment arbitrations have followed different interpretation strands of this principle, most notably Neer v. Mexico (1926), ELSI (United States of America v. Italy) (1989), and Glamis Gold v. United States of America (2009). Other tribunals, such as Mondev v United States (2002), para. 118, and Waste Management v Mexico (2004), para. 99, have undertaken a case-to-case approach and stated that it is not possible to agree upon what fair and equitable treatment ultimately means, as it all depends on the specific situations of each case (see also Dolzer & Schreuer, 2012, p. 139).

We contend that this same imprecision and vagueness may have negative effects if investment tribunals were to apply the definition of “fair and equitable treatment” pursuant to the PA-AP, CPTPP and USMCA. It will arguably have negative effects not only for State parties, but also for investors who claim a violation of this protection standard. There are no criteria to clearly establish if a violation did or did not occur, and that means that the outcome of arbitral judgements is difficult to predict. Thus, we argue that parties to the PA, the CPTPP and the USMCA should more clearly define such a provision in a convergent manner. Ideally, they should consider a unified regulation for investments. We believe that the PA Free Trade Commission, the Trans-Pacific Partnership Commission and the USMCA Free Trade Commission should jointly issue binding authentic interpretations (see below section on authentic interpretations) in order to unify the definition of “fair and equitable treatment” and force investment tribunals to interpret this principle in a convergent manner.

VI.3. Full Protection and Security

The principle of full protection and security in articles 10.6.2(b) PA-AP, 9.6.2(b) TPP and 14.6.2 USMCA requires each party to provide the level of police protection required under customary international law. This principle means a positive obligation for investment-receiving States to establish an internal regulatory framework that ensures and protects the foreign investments against possible conflicts with third parties (Schreuer, 2010, p. 354; Schill S. , 2016, p. 66). Thus, the host State must guarantee physical protection and security for investors and investments against the forceful interference of privates (such as employees, commercial partners or protesters) or State organs (such as the police and armed forces) (Schreuer, 2010, pp. 353-354, 368).

Article 1105 NAFTA required parties to accord full protection and security in accordance with international law, instead of customary international law. On 31 July 2001 the NAFTA Free Trade Commission issued an interpretation pursuant to articles 1131.2 and 2001.2(c) NAFTA and stated that “[t]he concepts of ‘fair and equitable treatment’ and ‘full protection and security’ do not require treatment in addition to or beyond that which is required by the customary international law minimum standard of treatment of aliens” (NAFTA Free Trade Commission, 2001). Interestingly, the above-mentioned PA-AP, CPTPP and USMCA rules do not follow the NAFTA text, but the NAFTA Free Trade Commission interpretation. Thus, there is a discernible trend in terms of incorporating the customary international law standard.

Investment Protection Rules

VII.1. Expropriation

Protection against direct or indirect expropriation is one of the bases of international investment law, as “protection against uncompensated expropriation ensures respect for property rights as a fundamental institution for market transactions” (Schill S. , 2016, p. 66). This rule, which has become an investment protection standard, is contained in articles 10.12 PA-AP, 9.8 TPP and 14.8 USMCA. They follow article 1110 NAFTA and article 6 US Model BIT 2012 (Herreros & García-Millán, 2017, p. 27; Polanco Lazo, 2015, p. 179). This rule is based on the “legality of expropriation” principle. It affirms that a State may expropriate foreign properties by implementing public, non-discriminatory measures that accord investors a prompt, adequate and effective compensation (Dolzer & Schreuer, 2012, p. 99). The PA-AP, CPTPP and USMCA prescribe that no party shall expropriate or nationalize a covered investment either directly or indirectly through measures equivalent to expropriation or nationalization, except for non-discriminatory measures that serve a public purpose and contemplate a prompt, adequate and effective compensation in accordance with due process of law. The reference to “due process of law”, while not included in all investment treaties, expresses the minimum standard of treatment of aliens in accordance with customary international law and the principle of fair and equitable treatment (Dolzer & Schreuer, 2012, p. 100), as previously mentioned. Article 10.12.1(d) PA-AP links due process of law to the minimum standard of treatment (article 10.6), whereas the CPTPP and USMCA do not.

Footnote 18 to article 10.12 PA-AP and footnote 17 to article 9.8 TPP define the scope of “public purpose” as referring to a concept of customary international law and add that domestic law may express this or a similar concept using different terms, such as “public necessity”, “public interest”, or “public use”, while the PA-AP adds “social interest”. The USMCA does not include an analogous rule.

Annexes 10.12 PA-AP, 9-B and 9-C TPP, and 14-B USMCA regulate the interpretation of articles 10.12 PA-AP, 9.8 TPP and 14.8 USMCA. Such annexes are fairly common in investment agreements in order to narrow down the spectrum of possible interpretations that arbitral tribunals may adopt, for instance regarding the controversial term “indirect expropriation” (Nottage, 2016, p. 318).

VII.1.1. Direct Expropriation

Pursuant to paras. 1 and 2 annex 10-12 PA-AP, annex 9-B TPP and annex 14-B USMCA, direct expropriation is an action or series of actions by a party that (substantially, pursuant to PA-AP) interferes with a tangible or intangible property right or property interest in an investment. Direct expropriation means that an investment is nationalized or otherwise directly expropriated through formal transfer of title or outright seizure. These provisions on direct expropriation are considerably clearer than, for example, the principle of fair and equitable treatment. Therefore, we anticipate that their application in investment tribunals will be more predictable.

Articles 10.12 PA-AP, 9.8 TPP and 14.8 USMCA use the terms “expropriation” and “nationalization” interchangeably. However, not all international investment agreements apply a “unified set of rules for expropriation and nationalization” and there has been much doctrinal discussion on the meaning of each term (UNCTAD, 2004, p. 63).

VII.1.2. Indirect Expropriation

Indirect expropriation is understood as measures taken by a host State that result in irreparable damage to an investment, provided there has been no transfer of legal title. Therefore, the measure does not affect the investor’s title, but deprives them from meaningfully using the investment. The rule of protection against indirect expropriation is fairly common in arbitral jurisprudence and investment treaties (Dolzer & Schreuer, 2012, pp. 101, 105-112; Herreros & García-Millán, 2017, p. 27).

Articles 10.12 PA-AP, 9.8 TPP and 14.8 USMCA provide that no party shall expropriate or nationalize a covered investment either directly or indirectly. Indirect expropriation refers to an action or series of actions by a party that have an effect equivalent to direct expropriation without formal transfer of title or outright seizure (para. 3 in annex 10.12 PA-AP, annex 9-B TPP and annex 10.12 PA-AP). These annexes, in their respective para. 3(a), almost identically add that to determine if an action or series of actions by a party constitute an indirect expropriation, a case-by-case, fact-based inquiry is mandatory that considers factors such as the economic impact and the character of the government action, and the extent to which the government action interferes with distinct, reasonable investment-backed expectations. Para. 3(b) adds that, except in exceptional circumstances, non-discriminatory regulatory actions that are designed and applied to protect legitimate public welfare objectives, such as public health, safety and the environment, do not constitute indirect expropriations. Annex 9-B TPP includes footnote 37 that lists examples of actions that protect public health.

Pursuant to articles 10.31.1 PA-AP, 9.16 TPP and 14.16 USMCA, measures regarding health and the environment are part of the State’s right to regulate. In accordance with APEC Non-Binding Investment Principles, originally endorsed in 1994 and revised in 2011 (APEC, 1994/2011), article 10.31.2 PA-AP condemns a race to the bottom, as article 1114.2 NAFTA did; interestingly, articles 9.16 TPP and 14.16 USMCA do not contain an analogous provision.

These provisions allow for the regulation of public welfare through non-discriminatory measures. Thus, they guarantee an adequate regulatory power for investment-hosting States. This protects States against frivolous investor demands claiming compensation for indirect expropriation.

Provisions on indirect expropriations have been subject to debate. That was the case for example in NAFTA investment arbitrations, and probably one of the main reasons was that NAFTA did not include an explanatory annex regarding expropriation (in contrast to the US Model BIT 2012 and the USMCA).4

The right to regulate is one of the most important elements in these investment chapters, because it guarantees States a regulatory space in matters of public interest (Herreros & García-Millán, 2017, p. 27). It is impossible to predict in abstract if this right, as framed in the PA-AP, CPTPP and USMCA, will encourage or discourage investments. It will ultimately depend on how future investment tribunals address that right on a case-by-case basis.

VII.2. Compensation

Articles 9.8.1(c) TPP and 14.8.1(c) USMCA state that expropriation must include prompt, adequate and effective compensation, whereas article 10.12.1(c) PA-AP does not. Articles 10.12.2 to 10.12.4 PA-AP, 9.8.2 to 9.8.4 TPP and 14.8.2 to 14.8.4 USMCA are virtually identical, as they specify the requirements for a compensation and whether compensation is denominated in a freely usable or non-freely usable currency. Articles 10.12.5 PA-AP, 9.8.5 TPP and 14.8.6 USMCA exclude the application of these rules to certain intellectual property rights, albeit in slightly different terms due to the fact that the PA-AP does not include a chapter on intellectual property.

In contrast to articles 10.12 PA-AP and 14.8 USMCA, article 9.8.6 TPP adds that, subject to certain requirements, a State’s decision on subsidies and grants in general does not constitute an expropriation. Thus, article 14.8 USMCA follows article 10.12 PA-AP more closely than article 9.8 TPP.

Article 14.8.5 USMCA includes an interpretation rule to determine if an action constitutes an expropriation, whereas the PA-AP and TPP do not.

Article 1110.2 NAFTA included valuation criteria for compensation. Somewhat surprisingly, the PA-AP, CPTPP and USMCA do not. Hence, arbitral tribunals will have to decide a valuation method for themselves.

There are still some gaps. Most importantly, the PA-AP, CPTPP and USMCA do not set a timeframe for determining when a compensation is paid “without delay”, they do not define who will assess those investments or how to assess them, among other issues. Parties to these agreements should answer such questions for these provisions to work properly and for these agreements to become an investment protection standard. If they do not, legal uncertainties and gaps may lead to disputes between States and investors. This, in turn, will most probably hinder investments in the Asia-Pacific region.

VII.3. Transfers

Another investment protection rule relates to transfers. Protection guarantees for capital transfers safeguards investors so that they freely transfer resources required for an investment and capital revenues from and to the host State territory. A transfer guarantee ensures “the free flow of capital and contributes to an efficient allocation of resources in a global capital market” (Schill S. , 2016, p. 66).

Articles 10.11 PA-AP, 9.9 TPP and 14.9 USMCA include this protection rule in similar terms. Articles 1109 NAFTA and 6 US Model BIT 2012 also include this standard clause. Articles 10.11.1 to 10.11.3 PA-AP, 9.9.1 to 9.9.3 TPP and 14.9.1, 14.9.2 and 14.9.4 USMCA contain almost identical example lists of covered transfers, rules on currency and rules on written agreements. Pursuant to articles 10.11.4 PA-AP and 19.4.3 USMCA, States may not require investors to make transfers, nor impose sanctions if investors do not make transfers; the CPTPP does not include an analogous provision. Articles 10.11.5 PA-AP, 9.9.5 TPP and 14.9.6 USMCA contain almost identical rules on transfers in kind, while articles 10.11.6 PA-AP, 9.9.4 TPP and 9.14.5 USMCA show some differences regarding transfer restrictions.

It is important to stress that investors will have to consider the domestic rules of PA and CPTPP parties, for example as stated in annex 10.11 PA-AP and annexes 9-E and 9-F TPP (there is no analogous USMCA annex). In our view, Chile’s reserved rights about restrictions or limitations on payments and transfers are compatible with the obligation to permit transfers “to be made freely and without delay into and out of its territory” according to articles 10.11.1 PA-AP and 9.9.1 TPP. However, we contend that, by analogy with articles 10.11.6 PA-AP and 9.9.4 TPP, those laws should be applied in good faith and in an equitable and non-discriminatory manner. We think that this interpretation is consistent with a discernible trend in these treaties towards respecting the States’ regulatory space. However, we concede that it would also be plausible to argue that those reservations are “incompatible with the object and purpose of the treaty”, according to article 19(c) Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties.

Performance Requirements

Another investment protection standard is the prohibition of performance requirements. This prohibition applies from the pre-establishment until the post-establishment stage. These provisions “seek to ensure a space for the host country to regulate public interest” (Herreros & García-Millán, 2017, p. 27).

Articles 10.8.1 PA-AP, 9.10.1 TPP and 14.10 USMCA refer to a first category of performance requirements. These agreements prohibit that host States impose or enforce certain requirements or enforce certain commitments or undertakings regarding foreign investors. Sections (a) to (g) are identical in these agreements and refer to export requirements, domestic content, technology transfer, etc. They are very similar to article 1106.1 NAFTA. However, articles 9.10.1 TPP and 14.10.1 USMCA add sections (h) on performance requirements related to purchase, use, or according preferences to technology, and (i) on license contracts. This constitutes a substantial difference that may affect investors and hinder normative convergence between the PA-AP on the one hand, and the CPTPP and USMCA on the other hand. For example, regarding license contracts such as franchise contracts, a PA party may require royalty rates to the detriment of future service-related productive chains. (Article 8.1 US Model BIT 2012 only adds section (h), albeit in a different version.)

A second category states that advantages shall not be conditional on certain performance requirements, such as domestic content, national purchases, foreign exchange inflows, etc. Articles 10.8.2 PA-AP, 9.10.2 TPP and 14.10.2 USMCA are quite similar, but article 14.10.2 USMCA includes an additional rule (e) about technology.

A third category is usually referred to as the host State’s right to regulate. The historical roots of the third category lie in article XX(b), (d) and (g) General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Building upon it, articles 1106.3 to 1106.6 NAFTA and 8.3 to 8.5 US Model BIT 2012 expanded this third category. Articles 10.8 PA-AP, 9.10 TPP and 14.10 USCMA further developed it. The first two categories prohibit certain measures, but articles 10.8.3 to 10.8.10 PA-AP, 9.10.3, 9.10.5 and 9.10.6 TPP and 14.10.3 to 14.10.5 USMCA allow such measures for the sake of public interest, if they are necessary to ensure compliance with domestic laws or regulations, to protect human, animal or plant life or health, or if related to the conservation of non-renewable natural resources and the environment. These articles are similar, with some important exceptions. The TPP includes article 9.10.3(c) regarding equitable remuneration under copyright laws, and article 9.10.4 about performance requirements related to employing or training workers in more detail than article 10.8.3 PA-AP and article 9.10.3(a) TPP. Articles 9.10.3(h) TPP and 14.10.3(g) USMCA explicitly state that the prohibition of first category performance requirements related to technology or license contracts (TPP and USMCA) and second category performance requirements concerning technology (USMCA only) does not exclude measures to protect legitimate public welfare objectives. The PA-AP does not include such a rule.

The third category is important because it guarantees the States’ right to regulate or adopt protection measures in relation to sensitive issues such as the environment, health and other regulatory objectives. In other words, investors bear the risks of not complying, e.g., with social or environmental national law. From a strictly economic perspective it may sometimes be inefficient to limit possible foreign investments, but from a broader viewpoint it is laudable to compel investors to make socially responsible and environmentally sustainable investments.

Investor-State Dispute Settlement

The PA-AP and TPP investment chapters include a Section B on ISDS, and the USMCA incorporates annex 14-D on ISDS between Mexico and the United States (thus excluding ISDS related to Canada). They follow the US Model BIT 2012. The USMCA also includes annex 14-C on NAFTA legacy and pending investment claims, while annex 14-E expands the scope of application to contracts, as mentioned before.

The US underwent a learning process: from NAFTA until around 2004, BITs signed by the US were rather favorable for investors. Starting around that time, ISDS has been subject to criticism in most parts of the world, especially regarding allegedly unsatisfactory levels of legitimacy and transparency, protracted and costly arbitrations, contradictory awards, arbitrators’ insufficient independence and impartiality in favor of investors, and arbitrators’ disregard for host States’ right to regulate, among others (Schill S. , 2015, pp. 1-2; Polanco Lazo, 2015, pp. 188-189; UNCTAD, 2013). Since the US Model BIT 2004, the US has signed BITs that are comparatively more favorable for host States. The TPP and the USMCA follow the same vein (Alvarez, 2016, p. 503; Herreros & García-Millán, 2017, pp. 27-28; Polanco Lazo, 2015, p. 179; Nottage, 2016, p. 346).

The section on ISDS led to much debate during the TPP negotiations. The United States, Australia and New Zealand, in particular, considered ISDS to be an offense to democratic sovereignty and governance, and a tool to debilitate the rule of law through the elimination of procedural safeguards by means of an inexplicable and irrevocable private justice system. They criticized that ISDS threatened the host-States’ right to regulate and that it was no incentive for FDI flows and therefore was of no help for the least developed or developing countries; additionally, they argued that ad hoc arbitration tribunals, for which there is no appeal, produce incoherent, poorly assessed arbitral awards that represent no legal certainty, as demanded by investors and States (Alvarez, 2016, pp. 503-515; Polanco Lazo, 2015, pp. 188-192). The real motivations are unclear: during TPP negotiations, Australia advocated for domestic tribunals as an alternative to ISDS (Polanco Lazo, 2015, pp. 190-191) and article 11.16 Australia-US FTA (signed in 2004) does not include ISDS; however, ISDS was included in FTAs Australia signed with Chile, China, Singapore. This example shows that that the real motivations for or against ISDS may not be legal or economic, but political.

Next, we will analyze the most significant ISDS provisions in these agreements.

IX.1. Consultation and Negotiation

A dispute settlement starts with the claimant’s written request for consultations (articles 10.15.2 PA-AP and 9.18.2 TPP). The USMCA does not specify how the dispute starts, but article 14.D.2.1 implies that the claimant requests consultations.

The consultation and negotiation phase is mandatory pursuant to article 10.15 1 PA-AP and optional according to article 14.D.2.1 USMCA. Despite the Spanish version using an indicative verb (“deben”), this phase is not mandatory pursuant to article 9.18.2 TPP, as the English version uses a conditional verb (“should”) and the English text prevails (article 30.8 TPP).

Consultations and negotiations are important as they provide investors with alternative dispute settlement mechanisms, including non-binding, third party procedures, such as good offices, conciliation or mediation.

IX.2. Submission of a Claim to Arbitration

Article 14.D.3.1 USMCA allows claims regarding breaches of NT or MFN treatment (with certain exceptions), or rules on direct expropriation (defined in annex 14-B, section 2), that have caused loss or damage to the claimant, thus excluding absolute standards and indirect expropriation. For Mexico and the US, full ISDS protection is only available pursuant to annex 14-E, i.e., regarding certain sectors including oil and natural gas, power generation, telecommunications and transportation services, and certain physical infrastructures. Article 10.16.1 PA-AP allows claims for breaches of any substantive obligations that have caused loss or damage to the claimant. Article 9.19.1 TPP allows claims for breaches of substantive obligations, an investment authorization or agreement, that have caused loss or damage to the claimant. Thus, the scope under USMCA is the narrowest, and under CPTPP the broadest.

Article 9.19.2 TPP allows States to make counterclaims, whereas PA-AP and USMCA do not.

The agreements have very similar rules on the next procedural steps (articles 10.16.2 to 10.16.7 PA-AP, 9.19.3 to 9.19.7 TPP, and 14.D.3.2 to 14.D.3.6 USMCA). The claimant has to deliver to the respondent a written notice of their intention to submit a claim to arbitration 90 days before submitting the claim. The claimant may choose arbitration under ICSID or UNCITRAL and, if both parties agree, any other arbitration institution and rules. The agreements include rules on when a claim is deemed submitted to arbitration, on temporal validity of procedural rules, and on arbitrator appointment.

IX.3. Consent to Arbitration and its Limitations

Rules on consent to arbitration are virtually identical (articles 10.17 PA-AP, 9.20 TPP and 14.D.4 USMCA).

Rules on consent limitation include different time limits. No claim shall be submitted to arbitration if more than three years (article 10.18.1 PA-AP), three years and six months (article 9.21.1 CPTPP), or four years (article 14.D.5.1(c) USMCA), have elapsed from the date on which the claimant first acquired or should have acquired knowledge of the alleged breach and the loss or damage.

Rules on the consent to the procedures, waiver submission and interim injunctive relief are virtually identical (articles 10.18.2 to 10.18.3 PA-AP, 9.21.2 9.21.3 TPP and 14.D.5.1(d) and (e) to 14.D.5.2 USMCA).

One of the more striking disparities relates to ISDS and national proceedings. Article 10.18.4 PA-AP adds an exclusionary rule on forum choice. If the claimant has previously submitted their claim to any other tribunal (including national tribunals), it will preclude an arbitration under the PA-AP. Annex 9-J TPP includes an analogous rule, but only applicable to certain parties including Chile, Mexico and Peru. Thus, in this regard annex 9-J TPP guarantees normative convergence for the three States that are parties both to the PA and the CPTPP. In contrast, article 14.D.5.1 USMCA requires the investor to first initiate a proceeding before national courts or administrative tribunals of the responding State, to obtain a final decision from a court of last resort of the respondent (unless such recourse is obviously futile) or wait for 30 months from the date the proceeding was initiated. Thus, there is a lack of normative convergence for Mexico regarding these agreements.

The claimant has four years (48 months) from the time they knew or should have known of the alleged infringement and the loss or damage. Proceedings before a national court may take 30 months at the most. Therefore, it follows from Article 14.D.5.1 USMCA that a diligent claimant should initiate a proceeding before national courts or tribunals no later than 18 months after they knew or should have known of the alleged infringement and the loss or damage. That is arguably a strict timeframe.

IX.4. Selection of Arbitrators

Articles 10.19.1 and 10.19.3 to 10.19.5 PA-AP, 9.22.1 to 9.22.4 TPP and 14.D.6.1 to 14.D.6.4 USMCA contain similar rules for selecting arbitrators, albeit the PA-AP includes a longer period before the Secretary General appoints the arbitrator. Professional requirements for arbitrators differ (articles 10.19.2 PA-AP, 9.22.5 TPP and 14.D.6.5 USMCA), but all agreements stress that arbitrators shall be independent (articles 10.19.2 PA-AP, 9.22.6 TPP and 14.D.6.5(b) USMCA).

Article 9.22.6 TPP elaborates on a code of conduct and conflicts of interest, while article 14.D.6.6 USMCA refers to challenges to arbitrators.

IX.5. Conduct of the Arbitration

The agreements contain several very similar rules con the conduct of the arbitration. Article 14.D.7.10 USMCA makes clear that arbitrations shall be expeditious and cost-effective.

IX.5.1. Legal Place of Arbitration

Articles 10.20.1 PA-AP, 9.23.2 TPP and 14.D.7.1 USMCA state that, as a general rule, parties may agree on any place of arbitration. If they do not, the tribunal determines the place within certain constraints.

IX.5.2. Third Parties

Articles 10.20.2 PA-AP, 9.23.2 TPP and 14.D.7.2 USMCA allow for third parties in almost identical terms.

IX.5.3. Amicus Curiae Submissions

NAFTA did not explicitly admit amicus curiae briefs, but investment arbitrators accepted them (Dumberry, 2002). In light of that experience, article 28.3 US Model BIT 2012 admitted amicus curiae briefs, albeit without regulating them in detail. Articles 10.20.3 through 10.20.5 PA-AP, 9.23.3 TPP and 14.D.7.3 USMCA contain quite detailed rules on this subject; in essence, the tribunal may allow amicus curiae submissions after consultation with the parties. TPP and USMCA rules are almost identical, while the PA-AP differs.

IX.5.4. Preliminary Objections

Rules on preliminary objections are quite similar (articles 10.20.6 through 10.20.8 PA-AP,9.23.4 through 9.23.6 TPP and 14.D.7.4 through 14.D.7.6 USMCA). One noteworthy difference is that TPP and USMCA rules allow the respondent to object that the claim is manifestly without merit, whereas the PA-AP does not.

IX.5.5. Burden of Proof

Articles 9.23.7 TPP and 14.D.7.7 USMCA place the burden of proof on the claimant. This rule is absent from the PA-AP and the US Model BIT 2012.

IX.5.6. Defenses

Articles 10.20.9 PA-AP, 9.23.8 TPP and 14.D.7.8 USMCA contain analogous rules on defenses and counterclaims.

IX.5.7. Interim measures

Articles 10.20.10 PA-AP, 9.23.9 TPP and 14.D.7.9 USMCA, regarding interim measures, are analogous.

IX.5.8. Interim award

Pursuant to the agreements, the tribunal shall issue an interim award at the request of a disputing party. Specific rules differ slightly (articles 10.20.11 PA-AP, 9.23.10 TPP and 14.D.7.12 USMCA).

IX.5.9. Appellate Mechanism

Although no ISDS multilateral standing appellate mechanism currently exists, quite a few treaties contain provisions for adhering to it in case it was created. Most are modeled on the 2004 and 2012 US Model BITs (van den Berg, 2019, pp. 4-11), so it comes as no surprise that articles 10.20.12 PA-AP and 9.23.22 TPP closely follow article 28.10 US Model BIT 2012. Remarkably, the USMCA lacks such a provision. We strongly support creating an appellate mechanism, as it would improve uniformity among arbitral awards, thus increasing legal certainty for host States and investors alike.

The Comprehensive and Economic Trade Agreement between the European Union and Canada includes an appellate tribunal to review awards on ISDS and dictates that it should be superseded in case of a multilateral appellate mechanism (article 8.28 and 8.29); however, these provisions have not entered into force nor are they provisionally applied pursuant to article 1 Council Decision (EU) 2017/38 of 28 October 2016 on the provisional application of the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) between Canada, of the one part, and the European Union and its Member States, of the other part.

IX.5.10. Discontinuance of proceedings

Pursuant to article 14.D.7.11 USMCA, the tribunal or the Secretary-General shall understand the disputing parties’ procedural inactivity as discontinuance of the proceedings. The PA-AP and CPTPP do not include such a rule; in our view, they should, as it provides legal certainty.

IX.5.11. Transparency

Transparency rules are almost identical and require public hearings and disclosing arbitration documents, among others (articles 10.21 PA-AP, 9.24 TPP and 14.D.8 USMCA). The main difference is that articles 9.24.5 TPP and 14.D.8.5 USMCA include a duty for the host State to sensitively apply its information disclosure laws, while article 10.21.5 PA-AP omits it. The fact that NAFTA did not include transparency requirements shows how expectations have changed in this regard.

IX.5.12. Governing Law

As mentioned above, the USMCA allows claims regarding the breach of certain obligations, the PA-AP allows claims for breaches of the host State’s substantive treaty obligations, and the CPTPP also allows claims for breaches of an investment authorization or agreement (articles 10.16.1 PA-AP, 9.19.1 TPP and 14.D.3.1 USMCA). Correspondingly, the agreements have analogous rules on governing law regarding claims for breaches of the host State’s substantive treaty obligations and applicable rules of international law, while the CPTPP also contains a rule on governing law for claims for breaches of an investment authorization or agreement (articles 10.22.1 PA-AP, 9.25.1 TPP and 14.D.9.1 USMCA).

IX.5.13. Authentic interpretations

Articles 10.22.2 PA-AP, 9.25.3 TPP and 14.D.9.2 USMCA, as well as footnote 1 to chapter 30 USMCA, make plain that the Commission’s authentic interpretations pursuant to articles 16.2.2(c) PA-AP, 27.2.2(f) TPP and 30.2.2(f) USMCA, are binding on tribunals. Under certain circumstances and with different timeframes, the tribunal may ask the Commission for an interpretation (articles 10.23 PA-AP, 9.26 TPP and 14.D.10 USMCA).

IX.5.14. Expert Reports

A tribunal may ask scientific experts for a report on factual issues (articles 10.24 PA-AP, 9.27 TPP and 14.D.11 USMCA).

IX.5.15. Consolidation

Two or more claims submitted to separate arbitrations may be consolidated if all parties to the dispute so agree. Consolidation rules are almost identical (articles 10.25 PA-AP, 9.28 TPP and 14.D.12 USMCA). The main differences are in section 5 regarding failure of the parties to appoint an arbitrator.

IX.5.16. Awards

The tribunal may award monetary damages and interest, and/or restitution of property (articles 10.26.1 PA-AP, 9.29.1 TPP and 14.D.13.1 USMCA), and a USMCA tribunal may not (probably meaning “must not”) order the responding State to take or not to take other actions (footnote 27). Article 14.D.13.2 USMCA requires satisfactory, not inherently speculative evidence. Articles 9.29.2 TPP and 14.D.13.3 USMCA limit recovery of loss or damage to investors of a party, whereas article 10.26.3 PA-AP requires that the investment is or will be made in the territory of the defendant. Tribunals may also award costs and attorney’s fees (articles 10.26.1 PA-AP, 9.29.3 TPP and 14.D.13.4 USMCA). Only PA allows tribunals and parties to allocate expenditures and costs (article 10.26.2).

As already mentioned, article 9.19.1 TPP allows claims for breaches of an investment authorization or agreement. Consequently, article 9.29.4 regulates what damages the tribunal may award in case of attempts to make an investment.

Articles 10.26.4 PA-AP, 9.29.5 TPP and 14.D.13.5 USMCA almost identically regulate the content of the arbitration award. A tribunal shall not award punitive damages (articles 10.26.5 PA-AP, 9.23.6 TPP and 14.D.13.6 USMCA). As generally in public international law, awards have no binding precedential value (article 10.26.6 PA-AP, 9.23.7 TPP and 14.D.13.7 USMCA, citing almost literally article 59 Statute of the International Court of Justice). Disputing parties shall abide by and comply with awards without delay in their territory (articles 10.26.7 and 10.26.9 PA-AP, 9.23.8 and 9.23.10 TPP, 14.D.13.8 and 14.D.13.10 USMCA).

Enforcement of final awards is subject to almost identical requirements (articles 10.26.8 PA-AP 9.23.9 TPP and 14.D.13.9 USMCA). If the host State does not comply, the claimant may request a panel (article 10.26.10 PA-AP, 9.23.11 TPP and 14.D.13.11 USMCA). Enforcement procedures are also virtually identical (articles 10.26.11 to 10.26.12 PA-AP, 9.23.12 to 9.23.13 TPP and 14.D.13 12 and 14.D.13.13 USMCA).

Rules on delivery of notice and other documents on notifying a change to the delivery place are almost identical (article 10.27 and annex 10.27 PA-AP, article 9.30 TPP and article 14.D.14 USMCA).

Additional Rules

The PA-AP includes section C on Additional Rules. It emphasizes the importance of promoting investments and social responsibility (articles 10.29 and 10.30). Article 10.31 stresses the host States’ regulatory space and condemns a regulatory race to the bottom. In addition, it creates a consultation mechanism regarding implementation of the investment chapter and a Joint Committee on Investments and Services (articles 10.32 and 10.33). Section C is not subject to dispute settlement (article 10.28 PA-AP). The CPTPP and USMCA do not include analogous provisions.

Conclusions: substantive convergence, procedural divergence

The general objective of this paper is to compare and analyze the investment chapters of the PA-AP, CPTPP and USMCA in order to determine their degree of normative convergence. Hence, in previous sections we reviewed and compared these chapters’ overall legal structure and individual rules.

While in this article we compared the authentic texts in Spanish, we also examined the TPP and USMCA versions in English. Strikingly, some TPP and USMCA rules are verbatim in English, but differ in Spanish as the agreements include synonyms or analogous expressions. The almost certain cause is that these agreements were negotiated in English and then translated into Spanish, but USMCA translators did not strictly follow the previous TPP Spanish text. This is most unfortunate, as the additional effort to achieve identical translations would have been negligible, and it would have considerably increased predictability and legal certainty.

In terms of convergence, we need to discern substantive and procedural (i.e., ISDS) rules.

First, regarding substantive rules on investments, these agreements primarily include definitions, rules on scope of application, treatment standards (NT and MFN treatment), absolute standards (international minimum standard of treatment, fair and equitable treatment, and full protection and security), investment protection rules (on expropriation, compensation and transfers), and rules on performance requirements. In this regard, PA-AP, CPTPP and USMCA investment chapters include convergent last generation international investment standards, such as regarding the host States’ right to regulate certain matters in accordance with legitimate public welfare objectives. We believe they represent a quite balanced model in terms of rights and duties for host-States and investors. This model provides legal certainty through clear investment rules for investors and a well-delineated right to regulate for host-States.

These substantive rules and principles are not identical, yet differences are mostly due to different wordings and in general do not severely affect the essence of the investment principles and rules. Moreover, Chile, Peru and Mexico managed to introduce significant exceptions to the TPP (such as annexes 9-E, 9-F, 9-J) that mirror PA-AP rules, so that both agreements converge more strongly for these parties.

Thus, we conclude that the substantive rules on international investment include rules that are generally convergent. We think that this convergence is at least partly due to the fact that many rules were ostensibly inspired by US preferences, as expressed in the US Model BIT 2012. Arguably, the more they converge, the more they will promote economic integration in the Asia-Pacific region (e.g. Toro-Fernández & Tijmes-Ihl, Service chaining model between the Pacific Alliance and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, 2020).

Second, concerning procedural (i.e., ISDS) rules and principles, these agreements require transparency and reasonable opportunities for public participation, thus judiciously preventing abuse and frivolous dispute settlement claims.

Regarding procedural convergence, our assessment is quite different from substantive rules. ISDS rules do vary to a significant degree. TPP and USMCA rules are often similar and frequently diverge from PA-AP rules.

In addition, ISDS rules on party coverage and protection coverage pursuant to the USMCA differ strongly from the PA-AP and CPTPP. Firstly, ISDS pursuant to the USMCA excludes Canada (except for legacy and pending claims). Second, annex 14-D USMCA is applicable to Mexico and the US, but excludes protection of absolute standards and indirect expropriation. According to annex 14-E, non-exclusionary ISDS protection for Mexico and the US is only available regarding certain contracts.

In a nutshell, we observe a paradox: substantive rules were molded after US preferences, with procedural rules applying partially between the US and Mexico, or only exceptionally between the US and Canada. (Moreover, since the US abandoned the TPP, TPP investment rules do not apply between the US and its former TPP negotiation partners). It should be highlighted that ISDS does apply between Canada and Mexico, including full protection coverage, as parties to the CPTPP. Thus, it seems that the US is not eager to apply ISDS to substantive rules the US itself has promoted, and/or that other States do not want to apply US-inspired ISDS vis-a-vis the US.

In conclusion, the low degree of substantive normative diversity allows the PA, CPTPP and USMCA to provide States and investors with two discrete, yet highly convergent investment regulatory frameworks. It is plausible that convergent regulations will offer incentives for investments. Thus, substantive convergence will provide opportunities for economic integration and will arguably promote and attract greater investment flows within and towards the Asia-Pacific region.

In contrast to substantive convergence, we found strong procedural divergence. Thus, we think that, by far, procedural rules will be the most important factor when claimants choose a forum. In a nutshell, we found that differences in substantive rules are not an obstacle for normative convergence, in contrast to procedural rules.

We argue that the next steps in terms of convergence among the PA and the CPTPP should start with concluding negotiations with CPTPP parties that are PA associate State candidates (Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Singapore, pursuant to the Guidelines Applicable to Associate States to the Pacific Alliance).5 In addition, CPTPP parties should start accession negotiations to the PA. Stronger convergence with the USMCA will not be possible through accessions, as the treaty does not allow it (in contrast to article 2204 NAFTA), and it would not make much sense due to divergent ISDS rules.

Another considerably more ambitious target would be to issue binding interpretations or even to renegotiate the investment chapters so as to achieve a unified investment legal framework for the PA and the CPTPP, especially on procedural matters, and perhaps also to renegotiate annexes 14-D and 14-E USMCA.

These steps would result in even higher degrees of legal convergence and an increasingly integrated investment platform

Referencias Bibliográficas

Alianza del Pacífico. (28 de abril de 2011). Declaración Presidencial sobre la Alianza del Pacífico (Declaración de Lima). Recuperado de https://alianzapacifico.net/download/declaracion-de-lima-abril-28-de-2011/ [ Links ]

Alianza del Pacífico. (s.f.). Lineamientos aplicables a los Estados Asociados a la Alianza del Pacífico. Recuperado de https://alianzapacifico.net/wp-content/uploads/ANEXO-LINEAMIENTOS-ESTADO-ASOCIADO-2.pdf [ Links ]

Alvarez, J. E. (2016). Is the Trans-Pacific Partnership's Investment Chapter the New “Gold Standard”? Victoria University of Wellington Law Review, 47(4), 503-544. https://doi.org/10.26686/vuwlr.v47i4.4789 [ Links ]

Amarasinha, S., & Kokott, J. (2008). Multilateral Investment Rules Revisited. En P. Muchlinski, F. Ortino y C. Schreuer (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of International Investment Law (pp. 119-153). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199231386.013.0004 [ Links ]

Chaisse, J. (2012). CPTPP Agreement: towards innovations in investment rule-making. En C. L. Lim, D. K. Elmsy y P. Low (eds.), The Trans-Pacific Partnership: A Quest for a Twenty-first Century Trade Agreement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139236775.015 [ Links ]

Dolzer, R., & Schreuer, C. (2012). Principles of International Investment Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press . https://doi.org/10.1093/law:iic/9780199211753.001.1 [ Links ]

Dumberry, P. (2002). The NAFTA investment dispute settlement mechanism and the admissibility of amicus curiae briefs by NGOs. Estudios Socio-Jurídicos, 4(1), 58-82. [ Links ]

Foro de Cooperación Económica Asia-Pacífico (APEC). (2011 [1994]). APEC Non-Binding Investment Principles (NBIP). Recuperado de https://www.apec.org/Achievements/Group/Committee-on-Trade-and-Investment-2/Investment-Experts-Group-2 [ Links ]

Furculita, C. (2020). FTA Dispute Settlement Mechanisms: Alternative Fora for Trade Disputes-The Case of CETA and EUJEPA. En W. Weiß y C. Furculita (eds.), Global Politics and EU Trade Policy. European Yearbook of International Economic Law (pp. 89-111). Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-34588-4_5 [ Links ]

Gallardo-Salazar, N., & Tijmes-Ihl, J. (2020). Dispute Settlement at the World Trade Organization, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, and the Pacific Alliance. Journal of International Dispute Settlement, 11(4), 638-658. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnlids/idaa021 [ Links ]

Gallardo-Salazar, N., & Tijmes-Ihl, J. (2021). The Pacific Alliance and the CPTPP as alternatives to WTO dispute settlement. Derecho PUCP, (86). [ Links ]

Gutiérrez Haces, M. (2015). Entre la observancia de los Acuerdos de Protección a la Inversión y el derecho a instrumentar políticas públicas de desarrollo en América Latina. En J. M. Álvarez Zárate (ed.), ¿Hacia dónde va América Latina respecto del Derecho internacional de las inversiones? (pp. 23-59). Bogotá: Universidad Externado de Colombia. [ Links ]

Herreros, S., & García-Millán, T. (2017). Opciones para la convergencia entre la Alianza del Pacífico y el Mercado Común del Sur (MERCOSUR): la regulación de la inversión extranjera directa. Santiago de Chile: Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe. [ Links ]

Manciaux, S. (2008). The notion of investment: new controversies. The Journal of World Investment & Trade, 6, 801-824. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-34588-4_5 [ Links ]

Nafta Free Trade Commission. (31 de julio de 2001). Notes of Interpretation of Certain Chapter 11 Provisions. Organization of American States Foreign Trade Information System. Recuperado de http://www.sice.oas.org/tpd/nafta/Commission/CH11understanding_e.asp [ Links ]

Navarro, J. (2016). The Trans-Pacific Partnership And The Pacific Alliance: Complementary Agreements Toward Higher Regional Economic Integration in The Asia Pacific Region. Vancouver: Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada (ABAC). [ Links ]

Nottage, L. (2016). The TPP Investment Chapter and Investor-State Arbitration in Asia and Oceania: Assessing Prospects for Ratification. Melbourne Journal of International Law, 17(2), 1-36. [ Links ]

Novak, F., & Namihas, S. (2015). Alianza del Pacífico: situación, perspectivas y propuestas para su consolidación. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Internacionales de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú y Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. [ Links ]

Polanco Lazo, R. (2015). El capítulo de inversión en el Acuerdo de Asociación Transpacífico: ¿una posibilidad de cambio y convergencia? En J. M. Álvarez Zárate (ed.), ¿Hacia dónde va América Latina respecto del Derecho internacional de las inversiones? (pp. 173-198). Bogotá: Universidad Externado de Colombia . [ Links ]

Rodríguez Aranda, I. (2014). Nuevas configuraciones económicas en el Asia-Pacífico y sus consecuencias para América Latina: desde el APEC a la Alianza del Pacífico. Dados-Revista de Ciências Sociais, 57(2), 553-580. https://doi.org/10.1590/0011-5258201416 [ Links ]

Schill, S. (2015). Reforming Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS): Conceptual Framework and Options for the Way Forward. Ginebra: E15Initiative. [ Links ]

Schill, S. (2016). International Investment Law and Comparative Public Law in a Latin American Perspective / Derecho internacional de inversiones y derecho público comparado en una perspectiva latino-americana. En A. Tanzi, A. Asteriti, R. Polanco y P. Turrini (eds.), International Investment Law in Latin America/ Derecho Internacional de las Inversiones en América Latina. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004311473_003 [ Links ]

Schreuer, C. (2010). Full protection and security. Journal of International Dispute Settlement, 1(2), 353-369. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnlids/idq002 [ Links ]

Toro-Fernandez, J.-F. (2018). Normative Convergence Between the Pacific Alliance and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Transpacific Partnership as a Way of Attracting Investments and Promoting Services Chaining with Asia-Pacific [tesis de LLM, Universität Heidelberg - Universidad de Chile]. Santiago de Chile: Heidelberg Center Latin America [ Links ]

Toro-Fernandez, J.-F., & Tijmes-Ihl, J. (2020). Service chaining model between the Pacific Alliance and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership. Mundo Asia Pacífico, 9(17), 5-21. https://doi.org/10.17230/map.v9.i17.01 [ Links ]

Toro-Fernandez, J.-F., & Tijmes-Ihl, J. (2020). The Pacific Alliance and the Belt and Road Initiative. Asian Education and Development Studies [preprensa]. https://doi.org/10.1108/AEDS-08-2019-0126 [ Links ]

Toro-Fernandez, J.-F., & Tijmes-Ihl, J. (s.f.). La Alianza del Pacífico y el Tratado Integral y Progresista de Asociación Transpacífico (CPTPP) [en prensa]. [ Links ]

Conferencia de las Naciones Unidas sobre Comercio y Desarrollo (Unctad). (2004). Glossary of key terms and concepts in IIAs. Ginebra. [ Links ]

Conferencia de las Naciones Unidas sobre Comercio y Desarrollo (Unctad). (2013). Reform of Investor-State Dispute Settlement: In Search of a Roadmap. IIA Issues Note(2). Recuperado de http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/webdiaepcb2013d4_en.pdf [ Links ]

Van den Berg, A. (2019). Appeal Mechanism for ISDS Awards: Interaction with the New York and ICSID Conventions. ICSID Review, 34(1), 156-189. https://doi.org/10.1093/icsidreview/siz016 [ Links ]

Zegarra Rodríguez, J. A. (2015). Los capítulos de inversión en los TLC y los TBI en Sudamérica, relaciones de conflicto o nuevos paradigmas. En J. M. Álvarez Zárate (ed.), ¿Hacia dónde va América Latina respecto del Derecho internacional de las inversiones? (pp. 199-218). Bogotá: Universidad Externado de Colombia [ Links ]

Jurisprudencia, normativa y otros documentos legales

Acuerdo Amplio y Progresista de Asociación Transpacífico (CPTPP) (Sistema de Información sobre Comercio Exterior de la OEA, s.f.). Recuperado de http://www.sice.oas.org/TPD/TPP/TPP_s.ASP [ Links ]

Acuerdo Marco de la Alianza del Pacífico (Sistema de Información sobre Comercio Exterior de la OEA, s.f.). Recuperado de http://www.sice.oas.org/Trade/PAC_ALL/Framework_Agreement_Pacific_Alliance_s.pdf [ Links ]

Acuerdo de Asociación Transpacífico (TPP) (Sistema de Información sobre Comercio Exterior de la OEA, s.f.). Recuperado de http://www.sice.oas.org/TPD/TPP/Final_Texts/Spanish/TPP_Index_s.asp [ Links ]

Marvin Roy Feldman Karpa vs. United Mexican States. Laudo, caso número ARB(AF)/99/1 (ICSID, 16 de diciembre de 2002). [ Links ]

Methanex vs. United States of America. Laudo final (Uncitral (Nafta), 3 de agosto de 2005). [ Links ]

Protocolo Adicional al Acuerdo Marco de la Alianza del Pacífico (Sistema de Información sobre Comercio Exterior de la OEA, s.f.). Recuperado de http://www.sice.oas.org/Trade/PAC_ALL/Index_Pacific_Alliance_s.asp [ Links ]

Salini Costruttori S.p.A. and Italstrade S.p.A. vs. Kingdom of Morocco. Decisión de Jurisdicción, caso número ARB/00/4 (ICSID, 23 de julio de 2001). [ Links ]

Tratado entre México, Estados Unidos y Canadá (T-MEC) (Sistema de Información sobre Comercio Exterior de la OEA, s.f.). Recuperado de http://www.sice.oas.org/Trade/USMCA/USMCA_ToC_PDF_s.asp [ Links ]

Received: October 30, 2020; Accepted: March 12, 2021

texto en

texto en