“… to raise ethnographic fieldwork to a professional art.” (Malinowski 1922: 15)

INTRODUCTION

Thank you for inviting me to participate in this important discussion. I am an elder in the discipline and I have prepared my remarks to reflect that; I expect a new generation to learn from but not be confined by my point of view, which is how I was taught to learn from Malinowski’s work. I organize my presentation in three parts: 1) The matter of Malinowski’s lineage stemming from his Trobriand fieldwork, in which I participate; 2) The current state of Research in the vicinity of the Kula Ring. My text is augmented by references in the bibliography, which is highly selective; and 3) The status of Malinowski’s tradition. Michael Young is the reigning Malinowski biographer (1998, 2004). In his terms, Malinowski’s ambition was “… to raise ethnographic fieldwork to a professional art” (Personal communication, September, 2022). Has that come about?

Malinowski was both a real person in a real time about which, both the person and the time, we can know a lot; and he was a founding, virtually mythical, figure, from which modes of action flowed which vary from his actual life. I can live with that.

Before I go directly to Malinowski’s work and heritage let me say that when I was a graduate student in the early 1970s I learned that John Murra used Malinowski’s model of the Kula Ring as an analogy to describe the vertical integration of Andean societies. When I visited Peru in 1998 Professor Ossio told me about ritual patterns consistent with that model. And because early in my career I researched aspects of the Kula Ring’s calendrical system Malinowski partly described, very soon I found Gary Urton’s first book, At the Crossroads of the Earth and the Sky (1981), exceptionally interesting. You will see me returning to that at the end of my discussion. Finally, I noted that Catherine Allen’s book, The Hold Life Has, invokes Malinowski’s prescription for how anthropologists should describe the societies they study. Andean studies should be in a dialogue with Indo-Pacific studies, and vice versa.

I. LINEAGES, FROM AND TO

Malinowski spent parts of two years in the Kula Ring between 1914 and 1918, beginning his written descriptions in 1918, a process that lasted for the rest of his life-he died young. After him Reo Fortune spent about 6 months among Dobuans of the southern part of the system; Leo Austen, a government official, conducted important research in the 1930s; Harry Powell did a bit of research in the early 1950s. Then from the late 1960s a new generation of scholars explored the area. When Malinowski, and to some extent Fortune, conducted their Kula Ring research that part of what is now Papua New Guinea was the center of colonial expansion. By the 1960s the region was close to a backwater. In any case, the new scholars include, Ann Chowing, Michael Young, Annette Weiner (1976), Nancy Munn (1986), myself (now for 49 months), Shirley Campbell, Debora Battaglia, Carl Thune, Maria Lepowski, Martha Macintyre; eventually Susanne Kuehling, Linus Digim’Rina and now a host of others. Susanne Kuehling (2005, 2021), a German woman now ensconced in Canada, probably begins the next generation of students. In one way or another, in whole or part, all of these people think of themselves as following in Malinowski’s footsteps, although many of us also follow other paths as well.

Mark Mosko, my age mate and to whom I shall return, leads a way in the next round of Trobriand studies (2017).

For many of us, Malinowski’s immediate students, Raymond Firth and Edmund Leach, defined our direct course studies. Like Malinowski, Firth was a great writer and ethnographer, but also with him many people saw the end of Malinowski’s overt theoretical positions. Edmund Leach, who considered himself both a student of Malinowski and Firth, maintained the writing verve one sees in Malinowski. 1994 was the last time I taught ARGONATUS and I was astonished, and pleased, to find students still fascinated by it. Yet Leach also charted new ways for thinking about the data. During the 1950s Leach wrote a series of essays re-interpreting Trobriand ethnography and re-conceptualizing Malinowski’s contribution (1950, 1957, 1958, 1961). If now probably incorrect, these essays are interesting, and well-worth reading today, not only for historical purposes.

Until they died, I kept both Firth and Leach apprised of my work and invariably received useful criticism from them.

In 1978 Jerry Leach, a Trobriand ethnographer who left the academy, and Edmund Leach organized a conference on the Kula at Cambridge University for all recent ethnographers. Firth and Reo Fortune were present, as was Andrew Strathern and Maurice Godelier representing contemporary English and French work in Melanesia, Godelier explicitly standing for the tradition of Marcel Mauss. This conference resulted in the 1983 THE KULA: New Perspectives on Massim Exchange, and does what its title suggests by filling in ethnographic gaps and providing new theoretical arguments about the region.

Michael Young considers himself at least partly Edmund Leach’s student; a great writer and competent Kula Ring ethnographer, he has made himself over the last 30 years Malinowski’s biographer. The first of his planned three volumes devoted to Malinowski is perhaps the greatest biography of an anthropologist ever written; the next two volumes should appear shortly. One of his Australian National University students, the Trobriand man, Linus Digim’Rina, assisted in Young’s discussion of Malinowski’s photography (1998) and has been the chair of the Department of Anthropology and Sociology at University of Papua New Guinea (UPNG) for many years. I maintain a lively relationship with Digim’Rina, frequently lecture at UPNG when I go through the country and keep him apprised of my work.

II. THE CURRENT STATE OF (ETHNOGRAPHIC) RESEARCH IN THE KULA RING, MILNE BAY PROVINCE, PNG

The 1983 publication, THE KULA: New Perspectives on Massim Exchange may have made teaching the system impossible because of the extent and quality of the information unleashed. But it marks a rough decade of pace-setting publications flowing directly or indirectly from the region. This work helped make Melanesian Anthropology the ethnographic and theoretical center of the discipline. Included in this work is Annette Weiner’s 1976Women of Value, Men of Renown. Weiner described an exceedingly important aspect of Trobriand culture Malinowski photographed but never described-there is a conundrum here (Damon, 2000). The book centered some of the feminist literature for several decades. Nancy Munn’s book The Fame of Gawa appears in 1986. A complex piece of work which, if infrequently read, along with her teaching, did much to animate some of the best anthropologists the University of Chicago produced over a 30-year period. And it gave fuel to the ‘materiality’ interest that has absorbed much of English and French anthropology from 1990 on. Chris Gregory’s 1982 GIFTS AND COMMODITIES, republished by Hau Books in 2015, comes out of this epoch as well not the least of reasons being that Gregory was specified as the youthful economic anthropologist in the 1978 Kula Cambridge Conference. There he fashioned the first draft of the thesis about alienation that animated GIFTS AND COMMODITIES. Drawing off of Weiner’s 1976 book and from Gregory’s Gifts and Commodities, among others, Marilyn Strathern produces The Gender of the Gift (1988), a book which helps make her central to Anglo-French anthropology similar to the way Malinowski once had been. Consequently, she delivered the final address at the 2015 conference held in Alotau, Milne Bay Province’s provincial capital, celebrating Malinowski’s centennial there: “Malinowski’s Legacy: One Hundred Years of Anthropology in the Milne Bay Province, Papua New Guinea.”

Drawing from Strathern’s work and in a direct line from Malinowski,1 Mark Mosko’s recent THE WAY OF BALOMA (2017; Damon, 2019) is the most intensive rereading of the Trobriand corpus there has ever been. Although not a participating observer, for ten years Mosko sat with a team of high-ranking Trobriand -mostly -men and carefully examined everything ever written by anybody about the place. Kuper’s blurb for the book is correct, that this is the Trobriand ethnography for the 21st century. ‘Kinship,’ ‘sacrifice,’ ‘mortuary rituals,’ political-cosmological hierarchies-all these are treated not only so that they update the ethnography of the place, Mosko creates an ethnographic account that should be used as a comparative foil for looking at other places, both near and far. It is no accident that Mosko implicates the Chinese idea of the tao/dao in his understanding of what he means by “way.”

Although there is good reason to continue the kind of anthropological research Malinowski chartered-examine carefully the life that appears to be in front of you-he erased virtually all historical inquiry from his published work. But now it is almost impossible to imagine that he did not see the stone structures scattered and concentrated about the landscapes of Boyowa and Kitava-I doubt he saw those in Muyuw. These are not idle relics: most of them are incorporated into Trobriand origin mythology and the largest Trobriand concentration of is near the place in the northern part of the island from where Trobriand clans are said to emerge. Only a few are really known in Muyuw but they are associated

Figure 1 Bunmuyuw. Adapted from Bickler 2006 Figure 3. This well-known set of ruins is one of many near Kaulay village in north Central Muyuw. A partial survey revealed two bodies, a common occurrence in the Kaulay ruins. All had heads pointing from east to the south, feet west to north. In the image here the foreground line of coral breccia runs more or less 113-294, roughly the December solstice sunrise to the June solstice sunset. The apparent series of lines running near perpendicular to that orientation may connect the rise of the Big Dipper to the setting of the Southern Cross, two complementary asterisms in Muyuw astronomy.

with strange trenches on the island. Muyuw people observe the trenches with care and use them to alter all-important garden forms when people find themselves gardening over them. This topic introduces a matter of much new research (Bickler & Ivuyo, 2002; Bickler, 2006). It now appears that these forms were built over a roughly 1000-year period, a time of massive public works throughout the Indo-Pacific. This historical phase ends about 1400, which is, given the current archaeology, about the time what we now know of the Kula begins to assume the shape it had when observed by the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries. At its extreme end of this new research is the work of the archaeologist Ben Shaw (2019; Shaw et al., 2020) who is tracing the earliest evidence of people in the region. Less than 10 years ago people are only known to be in the Kula region inside the last 2000 years, a nearly inconceivable fact given that human beings are known to be elsewhere in Australia and New Guinea 30-65,000 years ago. Shaw has now shown that humans are in the southeast sector of the region by 14-17,000 years ago. And there is increasing evidence of Austronesians being there by about 3000 years ago, at least 1500 years earlier than we would have guessed 7 years ago, and consistent with the arrival of Austronesian people and languages in this part of Melanesia. For most of the people in the Kula Ring region speak languages in the Austronesian language family. It remains the received wisdom that this language evolves out of East Asia, and probably southeastern China, some 6000 years ago. Then early Austronesians moved to Taiwan, and over the next 4500 years or so everywhere from aboriginal Taiwan to New Zealand, and Madagascar to Easter Island. Malinowski’s time saw the limits of one kind of historical time. Partly from the kind of data he helped us gather and come to understand, we can and should explore new dimensions in the histories of our globe.

From 1991 to 2017 I worked on environmental problems in the region, its ethnobotany. The focus of the inquiry was a tree (Rhus taitensis) which Muyuw people call gwed and Trobriand people the close cognate gweda. Almost everywhere across the northern side of the Kula Ring this tree is followed because people believe it reproduces the fertility of their soils. Understanding it involves following prescriptions first laid down by Malinowski, though he in fact knew very little about Trobriand gardening. That work has come to at least a provisional end with the publication of my book (2016), one which has stimulated Linus Digim’Rina and others to pursue its implications elsewhere.

III. MALINOWSKI’S TRADITION-AN ELDER’S POINT OF VIEW

According to Michael Young, Malinowski’s ambition was “… to raise ethnographic fieldwork to a professional art.” Too many other things have gone on to give a quick answer to the question of whether or not he did that. But before we get to our future it must be noted that Malinowski’s functionalism, especially his proscription that the details of social life be examined, had an overwhelming influence in US jurisprudence. The movement goes by the name “Legal Realism” (Kalman, 2010). Among others, the US Supreme Course Associate Justice William O Douglas (1898-1980) was a product of this movement. When I asked a legal professor in my university and about my age if he knew about “Legal Realism” he said “we are all legal realists now.” I’m not enough of a student of law in the US to know whether or not that applies to the younger legal scholars of today but I suspect the literalism (Crapanzano, 2000) that defines conservative legal movements in the US today constitutes a reaction against the cultural waves Malinowski did so much to instill a 100 years ago.

And this brings me to my concluding thoughts: In 1991 I started my second phase of research in the Kula Ring by first visiting Taiwan and the Peoples’ Republic of China. My idea was to be finished with that new Kula Ring work by 2000 and be well-ensconced in China. Things don’t always go the way you intend them, but I’ve had way too much intellectual fun for an old man. I’m now deeply into the last 6000 years of Indo-Pacific historical ecology and anthropology and am busy tracing the links and transformations between what ‘China’ became over that period and the Melanesian realities I have investigated. One of the things I learned about China has transformed my understanding of Muyuw. A Chinese expression is tiān dì, 天地, which is usually translated to something like ‘All Under Heaven.’ Formally this has to do with the way the Chinese Emperor had to act according to the prescriptions of the stars, from which power emanated. Sooner or later, this gets related to the Milky Way, which is said to be a Silver River in the sky taking liquids up to the mountains, that is going from east to west, whereupon the intersection of the earth and the sky results in fertilizing rain-and snow-and thence the major rivers, Yellow and Yangtze, moving from west to east. China takes most of its metaphysical and material realities from these reciprocal flows. ‘All’ Chinese temples have north/south orientations by virtue of their relationship to those rivers-the most sacred place is to the north facing south; of course, rice paddies get their sense from the ordered movement of water coming from, ultimately, the stars.

That similar ideas seem to have pertained to Andean realities is one of the reasons why I continue to be enticed by what we can learn from the ethnographic study of this region. Were there time I could run this out relative to the symbolism of the Chinese Emperor’s dress and the regalia that used to be the norm in Muyuw (and in a slightly different way, the Trobriands). I had thought that much of this ideology has disappeared; however, the grandson of one of my best teachers in the 1970s explained a lot of it to me in 2017, and it is clear he knows more than my limitations then could understand (my son is named after his father). This is for the future, mine or a successor.

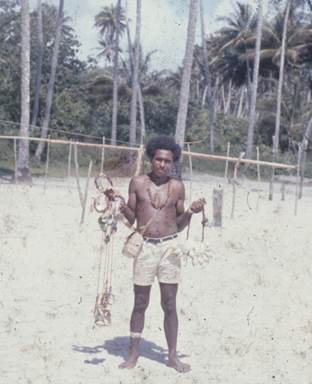

Figure 2 Damon’s photograph of Dibolel, circa 1974. Approximately 30 years old at the time of the photo, Dibolel was a young but ambitious man on the make in the Kula. He holds two newly made “armshells,” mwal, in his left hand, because they go to the right, and several “necklaces,” veigun, in his right hand, because they go to his left. In his hair is a comb, sinat, a word also used for the asterism we call Scorpius. In 2017 Dibolel’s son told me that had his father been really dressed properly, he would have tied one or more dried and marked leaves to the end of the comb. One of the images pressed into the leaf is a set of boxes said to be the likeness of stars-are the square to rectangular stone ruins models of stars on the land? Muyuw believe that powers that bring wind and rain come from stars, the twinkling of stars considered signs of that power. Fluttering leaves-on important people’s combs, decorated houses, boats and, especially, sails -are likewise taken as signs of heavenly powers. Important people are equated with important starts. At the time of this photo Dibolel was becoming an important person, and while now near death, he is such a personage. The imagery here is that of hierarchy and should be compared with the dress of the Chinese emperor who likewise embodied the heavens.

But this is anthropology…not all of our work can be or should be “art,” and not all of it should be about places that were once defined primarily as Other and Exotic. For years I’ve taught a course on US culture attempting to see to what extent the ideas and methods of anthropology -largely but not entirely Malinowski’s anthropology-may serve to enhance the understanding of my own society. Although over the course of my teaching-from 1977 to 2022-increasing numbers of anthropologists looked carefully at their own societies as anthropologists, I’ve had countless success employing books by two great journalists, Jane Kramer and her The Last Cowboy (1977), and Michael Lewis, especially his book about Wall Street, Liar’s Poker (1989). Kramer is married to the anthropologist Vincent Crapanzano and has been explicit about replicating the intensive ethnographic practices of anthropology. The Last Cowboy is the product of her spending a year leaving with a family in the Texas Panhandle. I’ve asked Michael Lewis if he explicitly follows anthropological methods, and he has told me no: I’m pretty sure he is lying. Liar’s Poker’s structure conforms exactly to the rites of passage forms Van Gennep and Leach laid out long ago. And it deals well with a topic Malinowski did so much to center in our discipline, the place of exchange and debt in human society.

If it be asked if the Malinowskian tradition should be alive and is well I think the answer to the first of these questions is “of course;” for the second we will have to wait and see.