During the last two decades, Chile’s migratory profile has shown significant changes related to a sustained growth of its immigrant population, and the increasing number of Latin-Americans newcomers, who represent 90.96% of the foreign inhabitants of the country (Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas, 2020).

One of the most important features of this new migration pattern is the increase of the school age children and adolescents segment, which corresponds to 15% of immigrant population (Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas, 2018). In fact, the number of foreign students on Chilean educational system was doubled between 2015 and 2017, representing 2.2% of the total student body. Immigrant students are mainly concentrated on primary education (64%), while 25% is enrolled on secondary schools, and 11% attend to pre-school education. It is also relevant to note that immigrant students tend to study mostly on public schools financed by the State but administered by local municipalities (58%) than Chilean students (36%), who are principally enrolled on subsidized schools (55%), financed by the State but administrated by private organizations. In both cases, only the 9% of the students attend to private centers (Ministerio de Educación de Chile, 2018). These data suggest an educational segregation tendency through which immigrant students are acceding to the schools with lowers socioeconomic profiles (Joiko & Vázquez, 2016),

Immigrant children and adolescents’ schooling is an emerging research topic on the local context, and there is growing evidence indicating intergroup conflict dynamics between Chilean and Latin-American students, as well as between them, their families and teachers. These studies have reported, mostly through qualitative designs, the existence of prejudices (Cárdenas, 2006; Navas et al., 2009; Navas & Sánchez, 2010; Salas et al., 2017), discrimination (de la Torre Díaz, 2011; Hein, 2012; Hernández, 2016), exclusion (Pavez, 2012) and racialization processes (Riedemann & Stefoni, 2015; Tijoux, 2013), which tend to be naturalized on school settings, and might have an important impact on teaching-learning interactions and also on school climate.

This new multicultural scenario is challenging for teaching staffs, who are key actors on cultural diversity management at schools (Gutentag et al., 2017). Teachers’ behaviors and attitudes toward multiculturalism have impact on students’ intergroup relations by influencing native pupils’ perceptions about their foreign peers (Horenczyk & Tatar, 2002). Likewise, educators’ beliefs, expectations and valuations about cultural minority students’ schooling processes are critical to their well-being and to their academic outcomes (Carter, 2006; Kao & Thompson, 2003; Pajares, 2007; Tyler et al., 2006; Verkuyten & Thijs, 2002; Wong et al., 2003).

In Chile, immigrants’ arrival to schools has been faced by educators on a brief period of time, with scarce preparation and lack of resources. Teachers have been educated on a monocultural system and prepared to teach to a homogeneous student body, through a professional training process that rarely involves the development of knowledge and skills related to multicultural education (Barrios-Valenzuela & Palou-Julián, 2014).

Furthermore, even though teachers may have access to establish close relations with immigrant families and get to know their sociocultural realities, some studies have shown that their perceptions of cultural diversity at schools tend to reflect general population attitudes to immigration on the larger society (Horenczyk & Tatar, 2002; Siqués et al., 2009; Vecina, 2006). Due to their position as members of the majoritarian society, teachers’ social identities might be threatened by immigrants groups (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), triggering ambiguous or negative reactions towards them.

Prejudice has been defined as a negative cognitive or affective response towards groups and their members, and it has a relevant role on the creation or preservation of intergroup hierarchical relations (Dovidio et al., 2010; Yzerbyt & Demoulin, 2010). As well as perceptions, judgments, beliefs and stereotypes about a group, emotions are an important component of prejudice (Tropp & Pettigrew, 2005), which are determinated by the effects of social interactions on status and power (Kemper, 1984). Moreover, these feelings contribute to intergroup boundaries’ delimitation and maintenance, by reinforcing group identities or preventing the contact between groups (Aberson, 2015; Keltner & Haidt, 1999). Thus, affective prejudice might leads to negative attitudes and behaviors toward cultural diversity (Aberson, 2015; Navas & Rojas, 2010), and it seems to be critical for educators whom emotions have impact on students’ affective experiences at school (Frenzel et al., 2017; Hagenauer et al., 2015).

Besides, several studies have shown that host societies members attitudes to multiculturalism, are negative related to the degree in which newcomers are perceived as competitors for material or symbolic resources (Sirlopú & Van Oudenhoven, 2013; Spencer-Rodgers & McGovern, 2002; Stephan et al., 2005; Vedder et al., 2016; Velasco et al., 2008; Ward & Masgoret, 2008). Realistic threat consists on the idea that immigrant groups represent a risk for natives’ access to welfare, job market or housing, and it can be perceived even when host society members’ individual interests are not in conflict.

Symbolic threat, in turn, entails the belief that immigrant groups systems of values and norms are incongruent with host society dominant culture, putting cultural homogeneity at risk (Stephan et al., 2005), which may be specially sensible for teaching settings. Threat perceptions lead groups to develop strategies to protect their own material interests and culture, diminishing their acceptance of diversity and avoiding intergroup contact (Bourhis et al., 2009; Florack et al., 2003; González et al., 2010; Montreuil et al., 2004), by their association to prejudice.

In the case of Chilean teachers, there is scarce evidence of their perceptions about multiculturality at school. A qualitative study conducted by Jimenez & Fardella (2015) found interpretative repertories which varied from cultural diversity invisibilization, to the perception of cultural diversity as a factor that hinders schooling processes’ normal development, preferring immigrant students’ segregation or assimilation to the mainstream culture. A third kind of approach consisted in the idea of multiculturality at school as a normal consequence of migratory processes, which doesn’t requires teachers adaptation but immigrant students individual efforts to fit in to the new context (Jiménez & Fardella, 2015).

In other research (Salas et al., 2017), conducted by a mixed method design, qualitative results showed that teachers believed that foreign pupils’ enrollment had several negative consequences to schools, such as the loss of prestige, Chilean families “scape” from their schools, and the worsening of education quality. Teachers on this study also tended to perceive that immigrant students have fewer learning capabilities than natives because of their cultural origin. As a consequence, they coincided on segregate them on separated groups inside the classrooms as a strategy to avoid Chilean pupils’ academic backwardness.

These findings seem to be consistent with results from studies with general Chilean population, which have aware about the construction of negative attitudes, low social recognition, racism and discriminative behaviors towards Latin-American immigrants (Mera et al., 2017; Thayer et al., 2013; Tijoux & Palominos, 2015; Valenzuela et al., 2014; Sirlopú & Van Oudenhoven, 2013).

Nevertheless, due to the importance of teachers’ role on immigrant students’ sociocultural integration, it is urgent to increase local knowledge production about their particular perceptions of school as a multicultural scenario, which poses the need of counting with adequate measurement instruments. Recently, Salas et al. (2017) made an interesting contribution by applying the Attitude to Multiculturality at School Scale (León del Barco et al., 2007), originally constructed with a Spanish sample, on 44 Chilean teachers, which results were analyzed and complemented with qualitative data. This work aims to be a new advance on Salas’ work, by validating and studying the psychometric properties of the Attitude to Multiculturality at School Scale (León del Barco et al., 2007) on a Chilean teachers sample.

Method

Participants

The sample was composed by N= 160 Chilean teachers, with ages between 23 and 65 years (M=40.40; SD=11.35). 70.6% were women and 29.4% had pedagogy degree studies, while 35.4% had postgraduate studies. 57.7% of the participants were primary education teachers, and 42.3% were teachers on secondary education.

Variables and Instruments

Attitude to Multiculturality at School: Attitude to Multiculturality at School Scale (León del Barco et al., 2007) was applied. This instrument was constructed with a Spanish sample, and it is composed by 8 items on a 5-point Likert scale (Completely disagree=1, Completely agree=5). Items are grouped on 3 dimensions: positive attitudes towards multiculturality at school (items 1, 2 and 3), negative attitudes towards multiculturality at school (items 4, 5, 7 and 8), and immigrant students’ aptitude versus natives (item 6). In the original study of León del Barco et al. (2007), the alphas reported were of .88 for the dimension negative attitudes towards multiculturality at school, and .83 for positive attitudes towards multiculturality at school dimension, while the general internal consistency of the instrument was α=.81.

Threat perception: To assess perceived threat we used a scale based on the Basque Observatory of Immigration Questionnaire (Aierdi et al., 2004), previously adapted to the Chilean context (Mera et al., 2017). It consists on 7 items with a 5 point Likert-scale (1=totally disagree; 5= totally agree), where 6 items evaluated realistic threat, while 1 item assessed symbolic threat (α(Cronbach) = .93; ω(McDonald)= .93).

Prejudice: Navas & Rojas (2010) Affective Prejudice Scale was applied, which consists on 11 items: 4 items including traditional negative emotions (fear, hate, disregard, irritation), 4 items including subtle negative emotions (indifference, distrust, insecurity, discomfort), and 3 items comprising positive emotions (respect, admiration, sympathy). Participants had to indicate, using a 5 point Likert-scale (1=nothing, 5=a lot), the degree in which they had felt each of these emotions towards Latin-American immigrants. In this study, the disregard’s item presented a low correlation with the total scale, thus, we opted to not include it on data analysis (α(Cronbach) = .87; ω(McDonald)= .87).

Procedure

Participants’ selection was conducted using a convenience sampling, according to schools availability and teachers’ voluntary participation. Eight schools agreed to participate in the study. All participants were informed about the goals and confidentiality conditions of the research, in order to comply with ethical and legal frameworks of informed consent. Questionnaire administration was done individually on schools, and had an average length of 20 minutes.

Data Analysis

The dimensional structure of the original model proposed by León del Barco et al. (2007), which is composed by 8 items, was examined through a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Different indices were used to evaluate the goodness-of-fit of the model: a) Chi-square, which must be not significant. Due to its sensitivity to the sample size, we also used b) Chi-square divided by degrees of freedom (χ2 /df), accepting values lower than 5 (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1996); (c) Comparative Fit Index (CFI); (d) Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI); and (e) Bentler-Bonett Normed Fit Index (NFI). For those indices, values equal and over .90 are considered acceptable, while values equal or over .95 indicate a good fit of the model. We also used (f) Parsimony normed fit index (PNFI), at which values above .50 are considered adequate; (g) Akaike’s information criterion (AIC), which is a comparative measure of fit between different models. Lower values indicate a better fit, thus, the model with the lowest AIC is the best fitting mode; (h) Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) at which values lower than .08 are accepted; and (i) Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), where values lower than.05 indicates an adequate fit (Bentler & Bonett, 1980; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Yu, 2002). In order to study the criterion validity of the Attitude to Multiculturality at School Scale (León del Barco et al., 2007), Pearson’s correlations analysis were calculated. Data analyses were conducted with the statistical software JASP V.9.9.

Results

Structural Validity

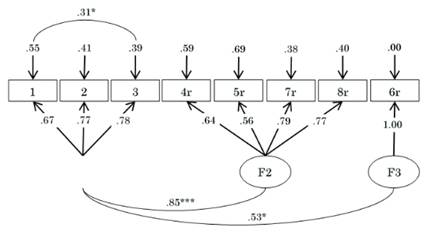

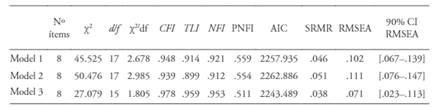

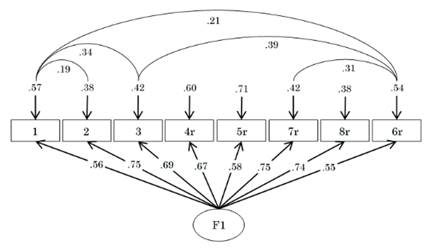

The original model (Figure 1), which consists on 8 items and 3 dimensions (Figure 1), was tested. The dimension “positive attitudes to multiculturality at school” is composed by items 1, 2 and 3, dimension “negative attitudes to multiculturality at school” includes the inverse items 4, 5, 7 and 8, and the third dimension, “immigrant students’ aptitude versus natives”, is composed only by the inverse item 6 (León del Barco et al., 2007). This model didn’t present adequate fit indices ((χ 2 (17, N=160) = 45.525, p. < .001; χ2/gl = 2.678; CFI = .948; TLI = .914; NFI = .921; PNFI = .559; SRMR = .046; RMSEA = .102 (90% CI [.067, .139]) ), as can be seen on Table 1.

Due to the inadequate fit of the original model, a bifactorial model was tested. The item which composed dimension 3 on the original model was included on dimension 2, affecting the goodness-of-fit of the model, with unacceptable results on the different indices ( (χ2 (17, N=160) = 50.476, p. < .001; χ2/gl = 2.985; CFI = .939; TLI = .899; NFI = .912; PNFI = .554; SRMR = .051 ;RMSEA = .111 (90% CI [.076, .147]) ).

Consequently, a unifactorial solution was tested (Figure 2). The third model presented satisfactory levels of goodness-of-fit ( (χ2 (15, N=160) = 27.079, p. = .028; χ2/gl = 1.805; CFI = .978; TLI = .959; NFI = .953; PNFI = .511; SRMR = .038; RMSEA = .071 (90% CI [.023, .113]) ). Scale’s reliability (α(Cronbach) = .865; ω(McDonald)= .876), assures its capability to differentiate between individuals who present a high attitude to multiculturality at school from those who show a low attitude to multiculturality at school. Table 2 shows descriptive data and reliability indices for each of the items.

Criterion validity

The literature review, previously presented on this paper, strongly suggests that attitudes to multiculturality at school are related to teachers prejudices towards immigrants, and also to the degree in which they perceived them as threatening both on realistic and symbolic terms. In order to study the instrument criterion validity, correlation analyses between attitude to multiculturality at school, prejudice and perceived threat were performed.

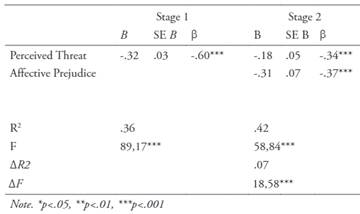

Results showed high negative significant relations between the attitude to multiculturality at school and perceived threat (r=-.60; p<.001), and also among attitudes to multiculturality school and prejudice (r=-.61; p<.001). Thus, positive attitude to multiculturality at school was associated with low threat perception and low prejudice.

A two stage hierarchical multiple regression analysis was also conducted, with attitude to multiculturality at school as the dependent variable. Results revealed that at stage one, perceived out-group threat contributed significantly to the regression model (F(1,159)=89,175, p<.001) and accounted for 36% of the variation of the attitude to multiculturality at school. Affective prejudice was introduced at stage two, explaining an additional 7% of the attitude to multiculturality at school variance (F(2,159)=58.836, p<.001). Together, these two variables explained a 42% of the variability of participants’ attitude to multiculturality at school.

Discussion

The aim of this work was to validate the Attitude to Multiculturality at School Scale (León del Barco et al., 2007) on a Chilean sample. Through a confirmatory factor analysis, we tested different structural models of the original instrument, confirming that the unifactorial model had the best fit to the data, and the internal consistency estimators presented adequate values.

Also, correlational analysis showed that consistently with precedents studies, the attitude to multiculturality at school presented high negative significant relations with threat perception (Sirlopú & Van Oudenhoven, 2013; Spencer-Rodgers & McGovern, 2002; Stephan et al., 2005) and prejudice (Vedder et al., 2016; Velasco et al., 2008; Ward & Masgoret, 2008). Moreover, the hierarchical regression analysis revealed that threat perception together with prejudice explained a 42% of the attitude to multiculturality at school variability, supporting the scale criterion validity.

It is relevant to note that the convenience sampling and sample size utilized in this study might represent important limitations which should be addressed in future researches with a more representative population of teachers. Nevertheless, we stress the importance of counting with an instrument which can be useful to detect teachers’ attitudes to cultural diversity at school, and further, to improve our knowledge about intergroup relations impact on immigrant students schooling processes, by identifying variables which can be key to psychosocial and educational intervention. Future research might also consider teachers’ acculturation attitudes toward immigrant students, and other important specific aspects such as their culturally responsive teaching skills (Gutentag et al., 2017). A deeper knowledge about these issues could contribute to the design of teachers training programs, which could improve their capabilities to cope with the challenges of cultural diversity, promoting positive intergroup relations at school.

We expect that this unifactorial version of the instrument could encourage scholars on this field to consider teachers’ perspectives on multicultural schools settings, especially in contexts where diversity management is a new and challenging task, such as in the Chilean case.