The theoretical and empirical association between negative life events, including traumatic, with changes in assumptive world or basic beliefs is firstly reviewed, as an instance of the “negative is stronger than positive effect” on psychological outcomes. However, this effect is at odds with the fact that a large majority, leaving extreme crises aside, report satisfactory wellbeing. Second, it is reviewed the evidence and arguments which suggest the opposite, or that positive life events and related emotions are not only more frequent, but they have stronger long-term effects on well-being (i.e. eudaimonic and purpose of life) than negatives ones. Third, post-stress and post-traumatic growth (PTG) is described as a complementary process explaining why people report satisfactory wellbeing in the long term, i.e. even negative events could induce positive changes. In post-stress traumatic growth, negative changes in basic beliefs or assumptive worlds are supposed to play an explanatory role, and evidence related to this point is reviewed. Evidence showing that not only negative, but also positive life events are associated with changes in basic beliefs is reviewed, and it is argued that positive life events provoke similar or higher personal growth than negatives ones, in part because positive events reinforce changes in basic beliefs to a greater extent that the erosion caused by negative events. The general link between the improvement of basic beliefs and growth is discussed as an alternative to the association between the shattering of basic belief and growth - which is specific to models of PTG.

Research suggest that, as a rule, negative events have a stronger and more durable impact on attention, judgement and affect than positive events, despite the fact that the latter are more common (Baumeister et al., 2001). Different mechanisms have been proposed to explain why “the bad is stronger than the good”. Negative events have more impact on people’s affectivity and thoughts, since these are generally contrary to their expectations and intentions, as well as being less frequent. Indeed, the frequency of negative emotional events is lower than the frequency of positive emotional events (Baumeister et al., 2001). It has been observed that people react more strongly, using more cognitive, emotional and physiological resources, in response to negative events (Taylor, 1991). People think more about them and make more effort to explain and deal with them than they do for positive events, even though they might involve the same need for readjustment. For example, studies of causal attribution showed greater efforts to explain negative events in comparison to positive ones (Mezulis et al., 2004). Studies on emotional episodes support that people deploy greater cognitive efforts when facing negative rather than positive events (Corsini, 2004). It has been proposed that the predisposition to respond more rapidly and intensely to negative events has an evolutionary basis: the cost of losing opportunities or resources is less than failing to perceive threats; therefore, in the development of the species this predisposition towards the negative has been selected as an adaptive trait (Baumeister et al., 2001).

However, as Taylor (1991) proposes, negatively loaded events have a strong short-term impact, but are minimized in the long term. Even traumatic events did not have an homogenous negative impact in basic assumptions or belifes. Regarding the impact of traumatic events on basic beliefs, comparisons have shown that subjects traumatized show more negative basic beliefs only in some dimensions than not traumatized subjects, and Only four of six traumatic events were associated to more negative basic beliefs (Janoff-Bulman, 1989). The reliability and structural validity of the scales of basic beliefs like Janoff-Bulman has been also criticized (Kaler et al., 2008). However, studies using other scales also show that only half of trauma have an effect and only in some dimensions (Catlin & Epstein, 1992). When some dimensions of beliefs are modified, basic belief did not becomes completely negative, but usually are less positive (Foa et al., 1999). Finally, only the subjects suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder report less positive basic beliefs - and only a third of the subjects exposed to potentially traumatic events suffer PTSD (Foa et al., 1999). Overall, the results suggest that traumatic events have a limited impact on basic beliefs

Not only the impact of negative extreme events on basic beliefs are limited, but also it was found that, the impact of positive emotional episodes on basic beliefs was greater than the impact of negative episodes (Corsini, 2004). Another study found that negative events were more weakly associated with Ryff’s eudaimonic wellbeing (Keyes et al., 2002; Ryff & Keyes, 1995; Ryff, 1989)despite an extensive literature on the contours of positive functioning. Aspects of well-being derived from this literature (i.e., self-acceptance, positive relations with others, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and personal growth, r (873) = -.06, than positive events, r = .24 (Bilbao, Páez, da Costa, & Martínez-Zelaya, 2013). Similarly, regarding the “purpose in life” dimension of eudemonic wellbeing, six studies show that positive mood states reinforce the attribution of meaning to life more than negative affect undermines the perception of such meaning (King et al., 2006).

Another element explaining long-term minimization of negative events effects would be that even extreme negative events might stimulate personal growth. Studies on post-stress growth compared to negative events have shown that 30-70% of people improve their vision of self and others after traumatic events (Cho and Park, 2013). Traumatic events can bring positive effects such as a feeling of personal growth, learning about one’s capacities and personal strength; discovering new opportunities, appreciating what one has and learning about life’s priorities; spiritual growth and development, being more tolerant and compassionate with others, and valuing the support they offer; and thinking that others can benefit from your experience, as cross-cultural studies have supported (Vázquez and Páez, 2011). This process of PTG is associated with the reconstruction of changes in the basic beliefs of the self, world, and others, and it is also referred to as assumptive world beliefs that people share about the world (just, controllable and meaningful), about the self (competent and worthy of respect), and about the others (Janoff-Bulman, 1992; Helgeson et al., 2006; Prati and Pietrantoni, 2009). Calhoun and Tedeschi’s (2011) model of PTG posits a positive relationship between the extension of change of basic beliefs and growth. Two cross-sectional studies showed that a significant disruption of beliefs is associated with high post-traumatic growth, and two longitudinal studies found that the change in basic beliefs predicts PTG, controlling the stress level (Cann, et al., 2009). However, other studies that measured changes in beliefs about the world as conducive to growth have not supported this theory (Park and Fenster, 2004). Finally, another study differentiates positive negatives changes in basic beliefs, and shows that negative changes in basic beliefs caused by traumatic events were associated with traumatic symptoms as well as with post-traumatic growth, but the positive changes were only related to the growth (García et al., 2014).

On the other hand, trauma is not necessary, and people can grow through positive life changes (McMillen, 2004). At least one published study found that positive events are linked to changes in basic world assumptions (Catlin and Epstein, 1992). As Fredrickson (2009) posits, positive emotions broaden attention, cognition, and behavioural repertoire, and consequently, we can suppose that they provoke positive changes in basic beliefs, helping to build long-term wellbeing.

In conclusion, the first objective contrasts the hypothesis that positive events reinforce positive beliefs about the self and the world more than negative events erodes them. A second objective is to test the hypothesis that positive life change events correlate with post-traumatic growth in a similar way to negative ones. In contrast, the alternative hypothesis proposes that only negative events are related with change. Finally, we examine the relationship between changes in basic beliefs associated with life-changing situations and forms of post-stress growth. Negative changes in beliefs about oneself lead, in a compensatory way, to the discovery of strengths, new opportunities and/or changes in one’s philosophy of life, as the PTG model and some studies suggest. Positive changes which are connected to the self and to the world linked to the life-changing situation should be associated with the perception of improvements in the self and in the world.

The first study uses a representative sample and compares retrospective perceived changes in basic belief and PTG from participants, when remembering a negative or a positive important life event. In the second study, we examine the valence of the event in a more differentiated manner, in order to discriminate between clearly negative events and clearly positive events and to check the role of intermediate events, i.e. important life events close to an ambivalent point on affective valence. The first two studies used a retrospective between subjects design and did not rule out dispositional differences. It could be argued that people low in optimism and high in neuroticism were over represented in the negative event group (Headey and Wearing, 1989). The third study used a random within subject design, asking people to recall and evaluate the most important positive and negative life events at the same time.

Study 1

Method

Participants

The participants in this study were 885 persons living in the Basque Country, who responded to a series of scales as part of a survey on collective violence and attitudes (ISAVIC). The sample was made up of 64% women and 36% men, with an age range from 17 to 93 (M = 48.56 years, SD = 15.3). In total, 15% of the participants mentioned a positive life event, while 85% mentioned a negative event. Data was collected by a social marketing enterprise using quasi-random sampling design and face-to-face trained interviewers.

Measures

The ISAVIC survey included a broad range of scales which purpose was to measure the effect of change events on people’s wellbeing. The classification variable for the participants was the life event chosen by the participant from the lists presented, e.g. Norris’s Traumatic Events and a Life Events List.

Traumatic Events (Norris, 1990; adapted by Páez et al., 1995): Norris’s scale measures the experience of seven traumatic events threatening life or one’s integrity, such as an imminent danger in one’s environment; damage to one’s goods or possessions resulting from a natural or man-made catastrophe; the traumatic death (accident, homicide or suicide) of someone greatly loved; a serious traffic accident; having been obliged to have some type of sexual relation by force or under threat; and having had something of yours taken away, through force or under threat, as in robbery or assault. The questions were used with a random Spanish sample, demonstrating their content validity and ease of understanding (Páez et al., 1995).

Life Events List (Bilbao et al, 2013): A list of life change events included 20 events selected from the Holmes and Rahe (1967) stressors scale, the study by Headey and Wearing (1989), and the work by Suh et al. (1996). Participants were asked to indicate whether the event in question had happened to them or not, and the time elapsed since it occurred: less than three months, three to six months, six months to one year, one to two years, two to three years, three to four years, and five or more years. The list contains seven negative change events (e.g., Did a close family member or friend die? Did you lose your job or fail in your studies?), and thirteen positive change events (e.g., Did you get promotion at work, or get very good grades in your studies? Did you make a new close friend?). Participants were asked “to choose the most important past event” of the list. This variable was divided into negative or positive for the analysis, according to the initial classification of the event’s content.

Impact on Beliefs Questionnaire (Impact of Beliefs Questionnaire IBQ, Corsini, 2004, translated and adapted by Bilbao et al., 2013): This scale assesses the situational or specific perceived changes in basic beliefs related to everyday emotional events by 12 items, six of negative changes in beliefs and six of positives changes in beliefs (see Table 1a for items). This scale has shown good reliability and criterion validity in two previous studies (Bilbao et al, 2013; García et al., 2014). Responses are scored on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (totally false) to 7 (totally true), and the instrument has good reliability, the negative changes in beliefs presenting a Cronbach’s α =.86, and the positives changes in beliefs of .87. An index of asymmetry of belief changes was calculated: positive minus negative changes. Higher and positive score means that improvements of basic beliefs predominate over negative changes.

Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (Tedeschi and Calhoun, 1996; short version, Cann et al, 2010; Cárdenas et al., 2015): This instrument rates the positive changes people perceive in the face of an impactful event. The short form of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI-SF) includes 10 items distributed in 5 post-traumatic growth dimensions measured in the original instrument. The psychometric properties of the Spanish adaptation are satisfactory (α=. 83). For the present study, the original instrument was abbreviated, leaving a scale of six items from the original one, with Likert-type response and a range of 0 = I have not experienced this change, to 5 = I have experienced this change to a very great extent (see Table 2 for items). The dimensions assessed are: Appreciation of life, New possibilities, Spirituality/Change, Relating to others and Personal strength. The scale showed good reliability, α = .80.

Procedure

Participants selected a relevant event from their lives that had made an impact on them personally. They would later be required to rate this event on a scale according to the degree to which they considered it positive or negative, from their personal point of view. Subsequently, for the event selected, participants responded to the Basic Beliefs and Growth scales according to how they experienced and dealt with it.

Data analysis

We carried out unilateral correlations with Pearson’s r and differences of means, with a statistical significance level of p < .05, using the statistical package SPSS 22.0 for Windows. Data was normally distributed and none extreme outliers were excluded. Bootstrap procedures were used to overcome potential parametric limitations.

Results

The analyses carried out by sex and age do not show significant differences or particular correlations according to the valence of the event experienced, and are thus not further reported in the results. Descriptive analyses about the impact of Basic Beliefs (IBQ) and Psychological Growth are presented according to the valence of the event in Table 1a. The most often mentioned negative events were the death of a family member or very close person (56%), illness or serious accident affecting a very close person (8.2%), illness or serious accident (5.7%), and experiencing the break-up of a marriage or intimate relationship (5.2%). The positive events most frequently chosen were an expected new birth in the family (54.6%), initiating an intense and satisfactory intimate relationship (9.2%), and a job promotion or obtain satisfactory grades (7.8%).

Life events and perceived changes on basic beliefs

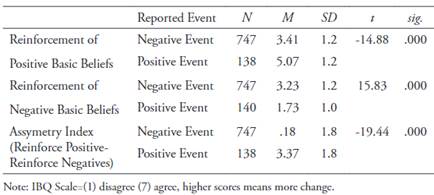

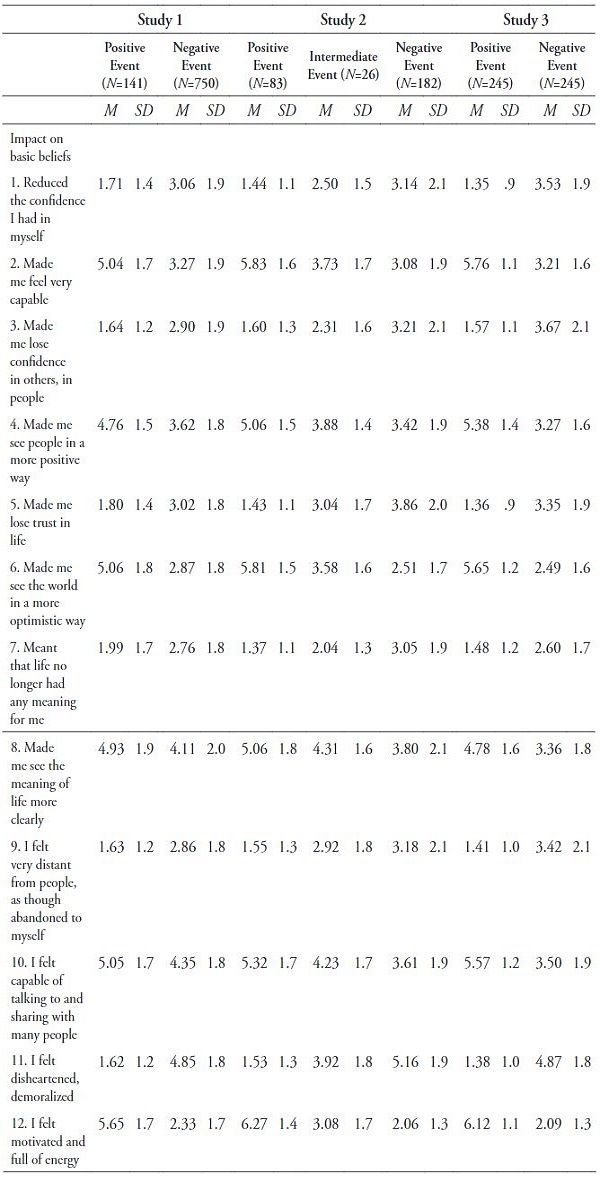

Table 1 shows the differences between groups on the impact on basic beliefs of the event experienced.

Table 1 Means and Standard Deviations of Impact on Basics Beliefs Quesstionarie’s Items by valence of event for 3 studies.

Participants who report a positive event have greater positive change in beliefs than participants who report a negative event. People who report a negative event present scores of negatives changes in beliefs close to the mean of the scale or neutral response, which implies that it is not associated to a swing toward negative basic beliefs. People reporting positive events strongly disagree on whether the event produces negative changes in beliefs. Finally, asymmetry scores show that positive events are strongly related with basic beliefs, while negative events are slightly more associated to positive than to negative changes.

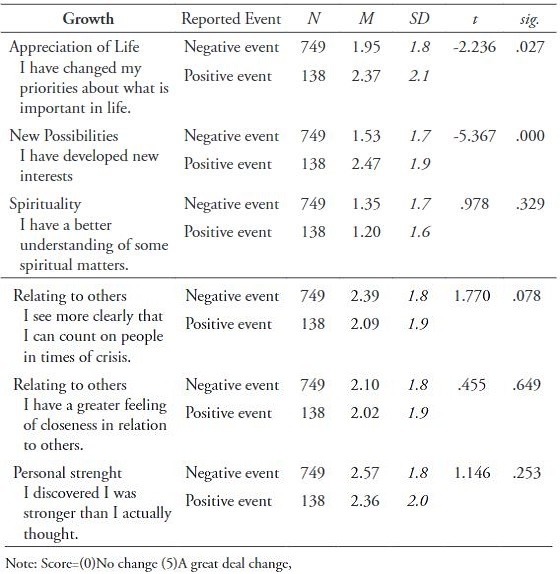

Change events and personal growth

For new possibilities and changes in appreciation of life, positive life events show a greater change than negative ones. Relation with others (greater appreciation of social support) shows a marginal difference between negative and positive events, being higher in the negative ones.

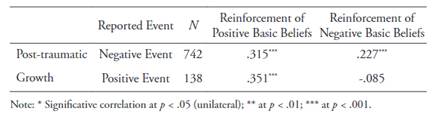

Change in basic beliefs and personal growth

Correlations between PTG and negative changes in beliefs found a positive association for negative events r(747)= .23, p < .001, and a non-significant negative association for positive events r(138)= -.085,n.s. Post-traumatic growth was related to positive changes in beliefs in the case of negative events r(747)=.31, p<.001 and positive events r(138)=.35, p<.001.

Discussion

This study shows that positive events were associated with the improvement of positive situational basic beliefs much more than with negative events undermining them. It was found that negative events did not increase positive beliefs, but participants also reported that they did not increase negative basic beliefs either. On the other hand, positive events were perceived as transforming basic beliefs into highly positive. It was also found that important positive events generated as much perceived personal growth after the change as negative events. The development of new possibilities and changes of life priorities were associated with both positive and negative life events, but strongly with positive ones. Perceived negative changes in basic beliefs were related to growth in the case of negative life events, supporting the role of the alteration of basic beliefs as a driver of post-stress growth - though this did not occur in the case of positive events. Positive changes in basic beliefs were associated with personal growth for both positive and negative events. This profile supports that a congruent socio-cognitive process is valid for all type of life events.

Study 2

This study contrasts a linear relationship between events and personal growth according to the emotional nature of the event, i.e. negative, intermediate or positive. A specific effect of negative events on post-traumatic growth predicts that only negative events produce the greatest change, with intermediate events and positive events producing no or less change. An extreme valence event hypothesis should be supported by a nonlinear relationship: intermediate events are associated with lower changes, while negative and positive are related to strongly perceived changes.

Method

Participants

The participants in this study were 291 students from a public Spanish University and their family members. All responded to a series of scales as part of their practical courses in Psychology and received academic credits for their participation. The sample was made up of 60.1% women and 39.9% men, with an age range from 17 to 73 (M = 35.8 years, SD = 15.3). In total, 31% of the participants mentioned a positive life event, 9.1% mentioned an intermediate event, and 63.1% mentioned a negative event. Participants received academic credits for their participation.

Measures

The Psychology practical course included a broad range of scales which purpose was to measure the effect of change events on people’s wellbeing. The participants answered Impact on Beliefs Questionnaire and Posttraumatic Growth Inventory with regard to the life event chosen from the lists of Traumatic Events and Life-Change Events.

Traumatic Events (Norris, 1990; adapted by Páez et al., 1994) and Life events List (Bilbao et al, 2013): Previous study measures were used. A question was added: those who recalled an impactful event were asked to rate the emotional valence of the experienced, from 1, highly negative, to 7, highly positive. This variable was divided, for the analyses, into three groups depending on the intensity indicated on the scale: Negative Event (1 and 2), Intermediate Event (3 to 5) and Positive Event (6 and 7).

Impact on Beliefs Questionnaire (Impact on Beliefs Questionnaire IBQ, Bilbao et al, 2013) : The measure of the previous study was used. Reliability was satisfactory for negative changes in beliefs, α= .86, and positive changes in beliefs, α= .87.

Post-traumatic Growth Inventory (Tedeschi and Calhoun, 1996; short version, Cardenas et al, 2015): Previous study’s measure was used. In this sample the scale showed good reliability, α =.80.

Procedure

Participants were instructed as in the previous study to select the most relevant event from their lives. They rated this event on a scale according to their valence. Subsequently, for the event selected, participants responded to the Basic Beliefs and Growth scales according to how they experienced and dealt with it.

Data analysis

We carried out correlations with Pearson’s r and differences of means -studying the linear or deviation of linearity relation of the association between variables-, with a statistical significance level of p < .05, using the statistical package SPSS 22.0 for Windows. Data was normally distributed and three extreme outliers were excluded. Bootstrap procedures were used to overcome potential parametric limitations.

Results

The analyses carried out by sex and age did not show significant differences. Descriptive analyses on the impact of Basic Beliefs (IBQ) and Psychological Growth are presented according to the valence of the event chosen in Table 4, divided into people who mentioned a positive event, an intermediate event and a negative event. The groups were made up of 29% (N = 83) extreme positive events, 9% (N = 26) intermediate events, and 62% (N = 182) extreme negative events. The most often mentioned negative events were the death of a family member or very close person (35%), illness or serious accident affecting a very close person (13%), and experiencing the break-up of a marriage or intimate relationship (12%). The positive events most frequently chosen were initiating an intense and satisfactory intimate relationship (21%) and having been accepted in a highly valued social group (21%).

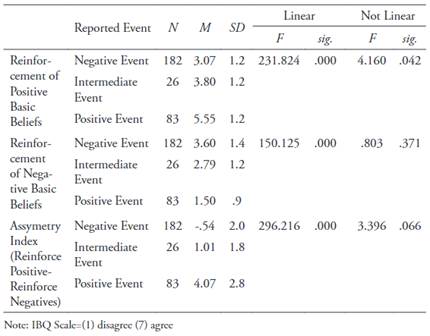

Life events and their impact on basic beliefs

Table 5 shows the differences between groups on situational changes in basic beliefs. Participants who reported a positive event show important positive changes in beliefs and disagree with negative changes. People who reported a negative event show low level of positive changes in beliefs, but also a mean score close to neutral point in negative changes.

Finally, a negative asymmetry score is observed in the group that experienced a negative event, a slightly positive score is reported in the intermediate group and those participants who mentioned a positive event report mainly positive changes in basic beliefs.

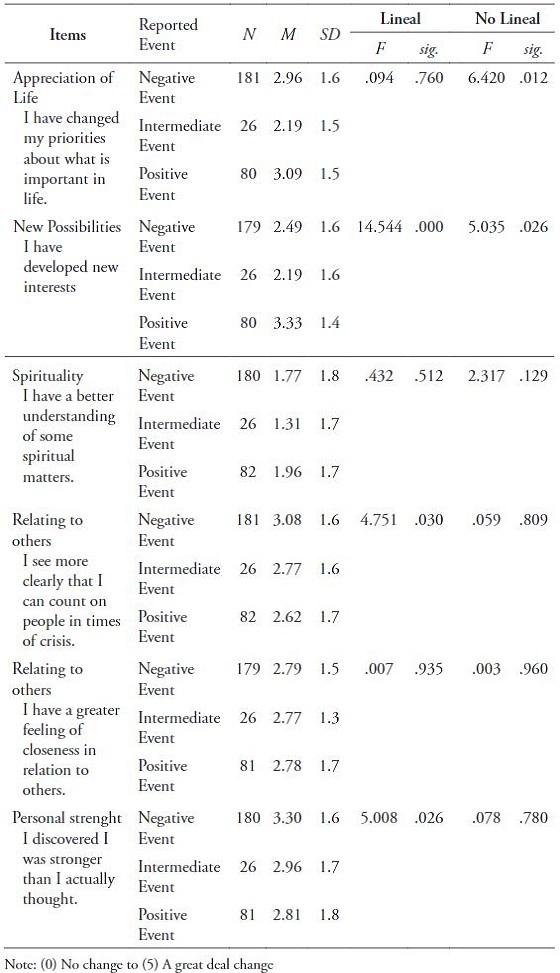

Change events and personal growth

A linear relation according to the emotional nature of the event was tested using one-way ANOVA: negative, intermediate or positive. Negative events would produce the greatest change, while intermediate and positive events would produce no or less change. This linear relation was supported for Relating to Others item: it is possible to account for others’ support and discovering personal strengths, with significant differences in this linear relation between negative and positive events. However, the linear relations for new possibilities show that positive events are associated with stronger changes than intermediate and negative events (see Table 6). On the other hand, for changes in appreciation of life, negative or positive events produced more change than intermediate events. Finally, changes in spirituality and relation with others showed no differences between negative, positive, and intermediate events.

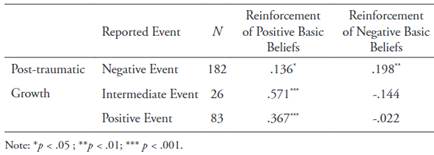

Change in basic beliefs and personal growth

PTG and perceived negative changes in beliefs show a significant correlation for negative events (r (182) = .20, p < .001), a non-significant negative association for intermediate events ( r (26) = -.14, n.s.) and positive events ( r (83) = -.022, n.s.). PTG was related to positive changes in beliefs in the case of all type of events, but the association was significantly weaker in the case of negative events (r (182) = .14, p < .001) than in the case of intermediate events (r (26) = .57, p < .001) and positive events (r (83) = .37, p < .001).

Discussion

Two-thirds of the important life events were negative, namely deaths or illnesses of family or friends; 20% were positive, such as the beginning of new intimate relationships. Around 9% reported important events of moderate valence, that is, slightly positive, intermediate, or slightly negative. This second study supports that positive events are associated with the perceived improvement of positive basic beliefs much more than with negative events undermining them. On the other hand, intermediate events show a middle increase in positive changes in basic beliefs and positive charged events were associated with strong positive changes. A linear relationship (negative events are associated with the greatest change, intermediate events to middle level, and positive events to low level of perceived change) was supported for Relating to others item: it is possible to account for others’ support and personal strength or discovering personal strengths. The first result replicates the first study’s finding, and it is fair to conclude that negative events help to understand the importance of received social support. The results also support Nietzsche’s statement that negative events increase personal strength - however, in the first study, increase in the personal strength was stronger in the case of positive events. The nonlinear relation for changes in appreciation of life suggests that these changes in life philosophy are associated with life events, and not only with negative or stressful events. The linear relationship for new possibilities suggests that these changes are associated with positive life events, and not only with traumatic or stressful events, as classically studied.

Finally, negative changes in basic beliefs are related to growth only in negative life events, supporting the role of the alteration of basic beliefs as a driver of post-stress growth. Positive changes in basic beliefs are associated with personal growth for positive, intermediate and negative events, supporting that a congruent socio-cognitive process is valid for all type of life events.

Study 3

This study replicated the two previous ones using a within subjects design to control any dispositional differences. The full version of PTG scale was used instead of the short version, in order to improve the reliability of the personal growth variable and also to explore differences in dimensions with higher accuracy.

Method

Participants

The participants in this study were 245 students of a public Spanish University who responded to a series of scales as part of their practical courses in Psychology. The sample was made up of 81% women and 19% men, with an age range of 20 to 52 (M = 22.68 years, SD = 4.01). Participants receive academic credits for their participation.

Measures

The Psychology practical course included a broad range of scales which intended to measure the effect of change events on people’s wellbeing.

Traumatic Events (Norris, 1990; adapted by Páez et al., 1994) and Life events List (Bilbao et al, 2013): Previous studies measures were used. A question was added: Those who recalled impactful events were asked to indicate what it was and with what emotional intensity they had experienced it with, from 1, highly negative, to 7, highly positive.

Impact on Beliefs Questionnaire (Bilbao et al, 2013): Previous study measures were used. In this sample reliabilities were satisfactory: for negative changes in beliefs, α = .79 for negative events and α = .78 for positive events, and for positive changes in beliefs, α =..77 for negative events and α = .82 for positive events.

Post-traumatic Growth Inventory (Tedeschi and Calhoun, 1996; Vásquez et al., 2006): The Spanish version of the PTG I 21 items was used in this study. In this sample the scale showed good reliability for negative events, with α = .95 for the total scale. The same occurs for the sub-scales, which show good reliability in almost all dimensions: α = .90 for Relating with other, α = .88 for New Possibilities, α = .82 for Personal strength , and was α = .83 for Appreciation of Life. The dimension with low reliability was Spirituality, and showed α = .44. Reliabilities were also satisfactory for positive events: Cronbach’s alpha of .95 for the total scale. α = .90 for Relating to others, α = .89 for New Possibilities, α = .86 for Personal strength, α = .81 for Appreciation of Life, and low reliability α = .41 for Spirituality.

Procedure

Participants selected two relevant personal events, one positive and other negative that had made an impact on their lives. Subsequently, for the two events selected participants responded to the changes in Basic Beliefs and Growth scales. Participants were randomly assigned to first answer the negative event and secondly the positive one, while the other half answer in reverse order. No order effect was found.

Data analysis

We carried out unilateral correlations with Pearson’s r and differences of means with a statistical significance level of p < .05, using the statistical package SPSS 22.0 for Windows. Data was normally distributed and four extreme outliers were excluded. Bootstrap procedures were used to overcome potential parametric limitations.

Results

The analyses carried out by sex and age did not show significant differences. The most often mentioned negative events were the death of a family member or very close person, illness or serious accident affecting a very close person (7%), family problems and conflicts with relatives (10%) and with friends (8%). The positive events most frequently chosen were participating in an emotional positive collective gathering (27%), initiating an intense and satisfactory romantic relationship (13%) and a non-romantic intimate relationship (7%).

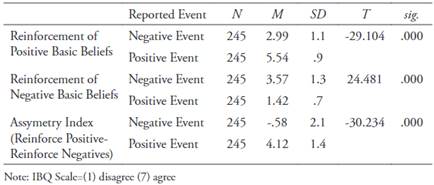

Life events and their impact on basic beliefs

Table 8 shows the differences between positive and negative events on perceived changes in basic beliefs.

Positive events scores show strong positive changes in beliefs and disagreement with negative changes. Negative events mean show a decrease in positive changes in beliefs, but also disagreement with negative changes.

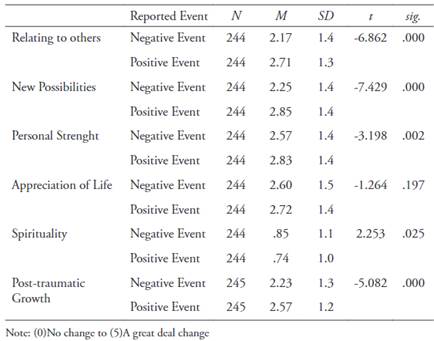

Change events and personal growth

Except for Spirituality, positive life events were associated with higher post-stress growth.

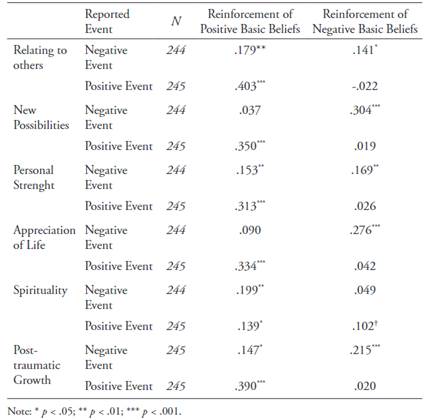

Change in basic beliefs and personal growth

Negative changes in beliefs correlated positively with global PTG and sub-dimensions, with the exception of Spirituality, in the case of negative life events. PTG total score and sub-dimensions were related to positive changes in beliefs in the case of positive and negative events, but the association was non-significant for negative events for Appreciation of Life and New Possibilities.

Discussion

This study based on a within subject comparison supports that positive events are associated with the reinforcement of positive basic beliefs much more than negative events increasing negative beliefs. It was found that negative events slightly decreased positive beliefs but did not increase negative basic beliefs. Perceived changes were higher in the case of positive events, suggesting that post-stress growth is associated with positive life events, and not only necessarily with traumatic or stressful events. It is important to remark that negative events are associated with PTG as large-scale studies show (Weiss & Berger, 2010). The important point is that positive events are also related to personal and interpersonal improvements. Replicating the two previous studies, a compensatory process was supported only for negative events: in this case, negative changes in basic beliefs are related to growth. Positive changes in basic beliefs are associated with personal and interpersonal growth for positive and negative events, supporting that a congruent socio-cognitive process is valid for all type of life events.

General Discussion

The results obtained show that around a third of participants recall a positive event as the most meaningful event in their lives, while two-thirds mention a negative one, supporting the idea that probably because its relevance for adaptation, negative events are more frequently chosen as important (Baumeister et al., 2001). Three studies test the hypothesis that positive events reinforce positive beliefs about the self and the world more than negative events. Results supported an asymmetrical profile: good is stronger than bad with respect to perceived changes in basic beliefs.

As shown in other studies on basic beliefs (Caitlin & Epstein, 1992), positive life events emotionally experienced as important have an impact on basic beliefs. This supports the hypotheses proposed, and everything is in line with the findings of King et al. (2006) on the central role of positive affectivity for increasing a sense of meaning in life. The results are very important, since they suggest that positive events are strongly linked with eudemonic wellbeing because they reinforce basic beliefs about self and the world more than negative events erode it.

Various processes would explain this asymmetrical effect of positive events on basic beliefs - processes that are linked to how information on events is analyzed, recalled and communicated. First, positive information is better analyzed and maintained for longer, due not only to the fact that it is less threatening and reinforces wellbeing, but also because positive information is simpler and easier to understand (Unkelbach et al., 2008). Second, there is a tendency for people to recall a greater proportion of positive events than negative events in the long term, and to reinterpret negative events so that they become less negative, to become neutral or even positive (Taylor, 1991). An example of this is when people recall positive events (related to pride) better than negative ones (related to shame). Moreover, this tendency has been seen to be stronger in people with high self-esteem (D’Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2008). This is due not only to the fact that positive life events tend to be more numerous than negative events, but also to the fact that the intensity of these positive events in the memory diminishes more slowly. This difference in rate of diminishment gives people a positive feeling on recalling their life events (Walker et al., 2003). Third, there is also a superiority of the positive in communication. This is reflected in language and its structure: positive words are used with greater frequency than negative ones (at least in Western societies), and the former are more primary and more representative of the totality of the concept or dimension (i.e. happy is more frequently used, simpler and represents the whole dimension of hedonic valence, while unhappy is secondary and more complex, and is only for part of the dimension (Matlin et al., 1978). Moreover, negative information is generally minimized or reconstructed in interpersonal communication (Taylor, 1991). These psychological tendencies tend to be stronger in rituals, monuments and other cultural products: what is negative for the social group is rarely commemorated, and what it recalls are events or facts that glorify the group as heroes or as martyrs (Pennebaker et al., 1997). We can conclude that the biases affecting personal and social memory are psychological mechanisms used for maintaining a positive self-image, and this explains the asymmetric impact of positive events in the long term.

Change events and forms of post-stress growth

Results show that growth after life events is relatively common, as occurs with stressful and/or traumatic events. This is congruent with research results on PTG (Helgeson et al, 2006). The results with regard to mean change in general (these are the aggregated means for PTG dimensions) show that people who had responded about negative events reported having experienced a change in Personal strength (x̄= 2.69) and Relating to others (x̄ = 2.39). They also reported having experienced a moderate change with regard to Appreciation of life (x̄= 2.36) and in New Possibilities (x̄ = 2.11). Likewise, they said they had experienced slight increases in Spirituality (x̄ = 1.25).

Results in one study show that negative events specifically produce growth effects like the reinforcement of personal strength, suggesting the truth of the dictum “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger”. In two studies, negative events were related to higher scores in the Relating to others item which is based on being able to count on people in times of crisis. The specific aspects of post-trauma or post-stress growth, then, would involve improving the image of the self through the discovery of strengths, as well as improving one’s capacity for receiving and valuing social support (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996).

In the three studies, forms of PTG like the development of new possibilities and change of life priorities were associated with both positive and negative events. This suggests that change events of either sign have common mechanisms and produce cognitive and motivational readjustments, changing goals and purposes, and reorient behaviour. Moreover, positive events are associated more strongly than negative events to changes of orientation in life toward new possibilities and increased social participation. This is coherent with the idea that positive emotional experiences increase psychological and social resources (Fredrickson, 2009); though it should be stressed that negative events are also associated with these forms of growth.

Change in basic beliefs and post-stress growth

Negative events were perceived as provoking positive changes in basic beliefs by an important minority - in particular concerning the attribution of meaning to life (46%, 41% and 27% in study 1, and 3 respectively) and relations with others (55%, 34% and 35%). Similar results were found in a large cross-cultural study by Scherer et al (1998). Episodes of anger and sadness provoke positive effects in the self-concept (15% and 12%) and in relationships with others (19% and 20%).

In the three studies negative changes in basic beliefs associated with the life-change situation were associated with post-stress growth in the case of negative events (r̄ (1164) = .22, p<.001). Overall, the results support that questioning beliefs serves as a driver of post-stress growth. On the other hand, positive changes regarding the self and the world related to the life-change situation were associated with perceiving improvements in the self and the world. This would occur, moreover, when the events were negative (r̄ (1174) = .26, p. < .001) or positive (r̄ (466) = .37, p. < .001).

This study has a series of substantial limitations. The fact that the data are retrospective, and the study does not include any instructions or stimulus that increase the salience of the event experienced mean that there is greater memory bias. Moreover, given that the data are cross-sectional there is no certainty that the sequence “life event-change in basic beliefs- growth” actually occurs in that order. Studies suggest that in cross-sectional retrospective assessments of PTG and shattered assumptions or changes in basic beliefs, an issue is that the participants may derogate their pre-event selves and beliefs and report deceptive growth to cope with the threat of remembering negative events (McFarland & Alvaro, 2000). However, results of the third study that examines both positive and negative event were similar to studies 1 and 2, in which participants remembering a negative event might even report a “fake” growth to deal with the event. In any case, it is necessary to carry out longitudinal studies to be able to explore in particular the relation between questioning of beliefs and changes.

Conclusion

The findings of this study support what Positive Psychology has set out to show in recent years: people have substantial personal and social resources for overcoming difficulties, enjoying pleasant experiences and being happy. As human beings, we can find strengths, positively reinterpret difficulties and find support in others. And finally, regarding the gathering of knowledge about different mechanisms that are involved in this process of coping and psychological growth, depending on the emotional intensity and the very nature of the life events, it is possible to develop social programmes or specific clinical interventions that nurture wellbeing by emphasizing the capitalization of positive events, but also of positive reactions to negative events, so as to go beyond the already existing approaches and strategies (Lyubomirsky, 2008; Seligman, et al., 2005).