The sexual assaults (precisely, the forced sexual coercion as a result of threats or already committed rape) have for many years been the focus of different books, research or newspaper reports and this subject still continues to exist as relevant important topic, being the ancient problem of our humanity. They remain an urgent task of educational and cultural life spheres in a lot of countries and a pressing policy challenge across many nations. It should be noted that there are already empirical and theoretical studies which can be used to inform the men’s growing involvement in the fight against violence (Macomber, 2018). We are sure that the introduction of traditional ancient Chinese philosophical-juridical thought and mindset will also provide significant positive results; in the China psycho-philosophical antic tradition, as one of the main points, the question of crime prevention for women and children reflects. Such an ideology succession between the China and Occident (and the Ancient East, in general) it is supposed to be very productive, especially since it is proclaimed today by the United Nations which emphatically emphasizes that the promoting of education for all and development of an equal, cooperating society would contribute to reducing crime (Jun, 2016).

The problem of sexual violence is very extensive and many-sided, so we divided it into the five following major groups providing each of them with a generalized description.

Sexual violence against women

Both accidentally encountered on the street, in a bar, etc., and during an intimate partnership. We suppose that the following scientific publications should be included in the list of the most significant recent research on this problem (Batchelor, 2017; Chafai, 2017; Classen et al., 2005; Começanha & Maia, 2018; Conley et al., 2017; Crandall et al., 2005; Daigle et al., 2009; De Àvila, 2018; Decker & Littleton, 2017; Djikanović et al., 2012; Donnelly & Calogero, 2018; Elmes et al., 2017; Fairchild & Rudman, 2008; Franklin & Menaker, 2018; Jayasuriya et al., 2011; Krahé et al., 2014; Kulig & Sullivan, 2017; Lindquist et al., 2013; Lisak & Miller, 2002; Littleton et al., 2008; Littleton & Dodd, 2016; Lown & Vega, 2001; Madan & Nalla, 2016; Mellgren et al., 2017; Natarajan et al., 2017; Rühs et al., 2017; Sambisa et al., 2010; Schuster et al., 2016; Vives-Cases & Parra 2016). This group includes victims of rape in a hidden - latent - form, but the study of statistics and behavior of latent victims in the scientific literature received very little attention (Grubb & Turner, 2012; Littleton et al., 2018; Loughnan et al., 2013; Maiuro, 2015; Strain et al., 2015; Wilson & Miller, 2015; Wood & Stichman, 2018). It should be mentioned that a certain discussion around the factors that may serve to either legitimize or to condemn sexual violence has appeared in the latest time. This debate concerns the social and cultural norms informing the people about what is right and wrong, and it is through their environment they learn how to behave (Bohner et al., 2009; Rudman & Mescher, 2012; Scarpati & Pina, 2017a; Scarpati & Pina, 2017b). To identify, disclosed and document the cases of sexual abuse and intimate partner violence, some of the researchers used certain models or conversation-methods, etc. with a special accentuation to enhance the memory capacity and its efficiency (Bhargava et al., 2011; Carotta et al., 2018; Paterson & Kemp, 2006; Rhatigan & Axsom, 2006; Sauerland et al., 2014; Vredeveldt et al., 2016; Vredeveldt et al., 2017).

Women with previous sad experience of sexual violence

Occurred in childhood, adolescence, or adulthood. Such women either eventually ended up in correctional institutions or were predisposed both to practice a risky sexual behaviour and to feel the negative self-esteem which lead to the heightened risk of revictimization because the protective factors such as their parents, caregivers, school and church became inactive. We’ve chosen only several of the research works on this tematics reguard that are worth to be cited (Chang et al., 2015; Comartin et al., 2018; Duwe & Goldman, 2009).

Men who have committed rape of women

Their internal problems, social backgrounds, personal characteristics, which stimulated them to commit a sexual violence. A great number of scientirfic articles and studies belong to the mentioned group of the researches, but we mention here only the most substantial, demonstrative and convincing (Abbey & McAuslan, 2004; Allroggen et al., 2018; Alzoubi & Ali, 2018; Bonta & Andrews, 2017; Davis et al., 2018; Gidycz et al., 2007; Jewkes et al., 2012; Masser et al., 2006; Seewald et al., 2018).

Men who have committed rape of children

As well as other types of violence against children. At the same time, the child physical abuse, the emergence of childhood sexual abuse and their seriousness are the best documented and investigated predictors of sexual victimization (Classen et al., 2005). This group of violence is also numerous, as the problem of children rape remains the most urgent and acute, and we share this opinion too because the children are the most vulnerable and least protected part of society (Anderson et al., 2017; Annitto, 2011; Barnert et al., 2016; Beech et al., 2012; Beier, 2016; Cole & Sprang, 2015; Crofts, 2017; Daly, 2014; Davis et al., 2012; Emetu, 2018; Filipas & Ullman, 2006; Fortier et al., 2009; Gibbs et al., 2015; Golding et al., 2018; Greenbaum & Crawford-Jakubiak, 2015; Greenbaum, 2014; Henry & Rowell, 2018; Hurrell, 2015; Jimenez et al., 2015; Leclerc et al., 2009; Lutnick, 2016; Papalia et al., 2017; Tal, Tal & Green, 2018; Varma et al., 2015).

Sexual abuse of marginalized society members

Homosexuals and prostitutes, including other forms of physical abuse as to them. Here we may citate the following works (D’Abreu & Krahé, 2014; Davies et al., 2008; Deering et al., 2014; Horan & Beauregard, 2018; Kubiak et al., 2018; Langenderfer-Manguder et al., 2016; Raj et al., 2006; Rothman et al., 2011; Stotzer, 2014).

Unfortunately, to date, most studies focus primarily on individuals who have committed sexual assault/rape, rather than on their victims, who are trying to continue their living in the normal course of life, and with this scientific thesis we completely agree (McPhedran et al., 2018). It is ascertained that the fact of being suffered rape causes a great harm to the health, working capacity, social and vital activity of the victims (adult or young women, men and children), because of the fear, shame, blame, infamy, injustice, posttraumatic stress, mental disorder and impunity for violator/offender that were injurious to the victims’ psycho-somatic status, social interrelations and internal psychological well-being just after the suffered sex abuse and are still damaging their present period of life (Anderson & Saunders, 2003; Davies et al., 2006; Greve et al., 2017; Hanslmaier, 2013; Kiernan et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2012; Lee & Hadeed, 2009; Lemieux & Coe, 1995;Orchowski et al., 2013; Riccardi, 2010; Ring, 2017). This fact seems to us to be especially important and relevant.

At present the victim-survivors of sexual violence have found the way out engaging with Internet and digital technologies for as a way to feel some relief for own bitter, hard and, speaking more precisely, tragic fate (O’Neill, 2018). The limitation of knowledge related to victims is that the victims of sex-violence often (for various reasons) do not provide any information about their own sad/tragic personal experiences and circumstances. In our study, as its preliminary baseline, at first the dominant causes that lead to a latent (latent) form of sex-violence are considered. It is quite clear that the violence in a latent form cannot be included in statistical reporting and remain as facts unknown to the police. The number of latent victims is large enough, and unsolved sex crimes, remaining in a hidden and unpunished form, continue to provoke a psychosomatic destabilization in the victim’s life and damage their health. That is why the focus of our research was aimed at reducing the latent form percentage of sexual violence of women and developing strategies for the rape/violence prevention.

In general, up to six out of ten women experience physical and/or sexual violence in their lives. The study results of analyzing 24,000 women in different countries, this analysis was conducted by the World Health Organization, showed that the prevalence of physical and/or sexual violence from a partner varies from 15% (in urbanized Japan) to 71% (in agrarian Ethiopia). For the young girls aged 14-16 years, the violence and sexual abuse are the principal causes of death, suicide and disability.

According to the reports of the Ukrainian Ministry of Internal Affairs, nearly 600-700 rapes/assaults and 2,500 murders/attempts at murder are being perpetrated per year in Ukraine, the last ones happen four times more than rapes at that. It seems illogical, exceeds the limits and goes beyond the criminology laws, at least because in order to perpetrate a murder, the person must overcome much more ethic-moral and emotional suppressing, restraining factors than in the case of rape, which is evidenced by the statistics in developed countries, where the fight against criminality, the delinquency registration and crime detection are organized much better than in Ukraine.

In the United States, for example, each year up to 6 murders and nearly 92 rapes per 100 thousand people are committed. In Britain, the killings index is 1.4, the rape one is 14.2; in France - 1.7 and about 14 accordingly. Ukraine shows a similar to Russia dynamics, where approximately 19.2 murders per 100 thousand people are committed each year, but less frequent rapes are surprisingly registered, namely, about 6 cases per 100 thousand. But if we focus on a more accurate European statistics, the Ukrainian official reporting should show 10 times more rapes: about 6-7 thousand cases per year (Nightmare in Nikolaev, 2012; People in Ukraine look at sexual crimes with widely closed eyes, 2012; Prosecutor’s office could not stand the pressure of the press: rapists-arsonists were put in a cage, 2012; Terrible numeral, 2017; You are so beautiful, drink a sip, 2018). According to Tatiana Montyan, a well-known Ukrainian lawyer, the point is that «... only one out of ten raped women applies to the police. People do not want publicity and seek to negotiate without trial» (Rape in Ukraine, 2012).

In the Russian Federation, only about 12% of all victims of rape are being treated by the police, and in the United States - about 16%. As for Ukraine, such studies have not been conducted and we can only assume, basing on the worldwide trend, that in our country approximately 10-20% of all rape victims apply to the police. Therefore, if we take as a basis the data from Ukrainian official statistics (i. e., 600-700 registered cases per year), then from 2.4 to 6.3 thousand of sexual violence acts remain hidden from police reports each year. And given the fact that the “official” figures should be at least ten times higher, so really (taking into account latent crimes which were not declared) 60-70 thousand rapes are committed annually in Ukraine (Timchenko & Khrystenko, 2004). That’s why the specific purpose of our research was to demonstrate the results of using the transformed-interview method for studying the latent victims of sexual violence committed in the territory of Ukraine.

Statement of the main material

In the criminological investigations, in general the offender’s behavior is exclusively focused, while the interrelationship between the behavior of different non-criminal population types and those of criminality manifests much less interest. However, this relationship is decisive for understanding the deep-laid causes of crime and the identity of the criminal/offender himself. Among the persons who come into contact with the offender in one way or another, it is the victim who is in direct relationship with the offender.

Urgent necessity to study the victim of a crime was fully apprehended and understood by the scientists of various countries only after the Second World War. In the post-war period, the urgency of the problem with the behavior of crime victims led to the emergence of a new scientific psychology branch - victimology. First victimological research works were carried out in 1945 in Japan, some later in 1946-1947 in the countries of Europe and America (Ueda, 1989).

The psychology of the victims’ behavior belongs to such type of investigation categories where a direct experiment is impossible since it may endanger the victim’s mental health. Therefore, there is a need to expand the methods of victim research with the inclusion of the mathematical modelling method, which under these conditions is practically the only possible method for collecting information, its analyzing, and forecasting such crimes.

In accordance with the aforementioned statement, the purpose of our study was to prove the effectiveness of the use of the transformed interview method in investigating the crimes of sexual violence.

Having specified the victimology of the environment and the features of the victim’s behavior psychology, it is possible to significantly heighten the efficacy of law enforcement apparatus that in its turn allows one to reduce their economic maintaining costs by means of: (i) preventive measures aimed at changing the behavior patterns of potential victims (“potential victims” means the category of citizens who are most likely to be victims of sexual violence, the so-called “risk group”); (ii) specialists’ training that takes into consideration the needs of the concrete moment; (iii) growing effectiveness of the law enforcement personnel when disclosing every particular crime. The principle of the environment and behavioral forms unity requires a joint analyzing examination not only of the victim and the perpetrator, but of the social conditions which cause, generate the victim’s appearance, and of the social conditions that give rise to the offender. This explains the need to study the effectiveness of using the mathematical modelling method in practice of the juridical psychology, criminology and victimology.

The method of modeling (the transformed interview method, as we named it) consists in obtaining the information not from the object of research, but from his surrounding representation model. Achievements in various branches of mathematics, cybernetics and synergetics allow realizing the model descriptions of a person’s mental activity. This method permits us to abstract from specific individuals and receive information about the general regularities of human behavior.

In addition, this method can contribute to increasing the psychological and social performance of the police personnel. Our previous studies have confirmed that personal-professional efficiency is achieved by enhancing the interrelation of a person’s internal values with the socio-psychological factors of his life, thereby revealing his recreational potential, mobilizing resources and increasing productive-energetic output, and at the same time forming personal qualities oriented to axiological perspective: in this way, a person enters into a deterministic (i.e., foreseen and predefined) process of his permanent further development (Ivanchenko, 2017; Ivanchenko & Zaika, 2017; Ivanchenko, et al., 2018).

At the initial moment of interaction with the offender, the victim has a certain level of security. This level is determined by the victim’s temperament, character traits, physical abilities, social security, etc. During interaction with the offender, the victim reduces own initial level security (exhaustion of mental and physical forces), that is, the initial level of victim’s protection decreases. The more fast this change in initial personal security, the more often the victim uses it, while resorting to various forms of behavior (the more moves, the greater the expenditure of physical forces, etc.). As a result of defensive actions, the initial capabilities of the victim are consumed. In addition, the perpetrator acts on the victim, trying to achieve the desired, thereby also changing the current security of the victim.

Similarly to the above made analysis of the victim’s security level, we can describe the level of the offender’s possibilities to commit a crime.

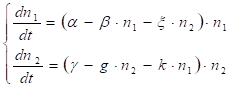

Relations between the victim and the offender are interdependent, therefore they can be presented in analytical form as a system of equations (1):

where: n 1 - actions of the victim; α - the initial level of the victim’s overall security at the moment of interaction with the perpetrator; β - the speed of self-restraint by the victim of the own security level; x - reducing the victim’s protection level because of the offender’s influence; n 2 - actions of the offender; g - the initial level of the offender’s possibilities at the instant of the attack on the victim; g - the offender’s self-restriction of own opportunities and possibilities; k - reducing the offender’s opportunities and possibilities due to resisting him on the part of the victim.

In this system of equations, the special attention should be paid to the suitable coefficients, namely: those that contribute (α, у) and those that prevent (β, ξ, g, k) the achievement of the goal, set by each side.

Just at the moment of criminal assault, the victim, using own capabilities (coefficient α), causes some damage to the offender, reducing his chances of achieving the goal. But at the instant of interaction the victim’s forces are also spent, and the ratio of these coefficients indicates on which side the victory will prevail.

The equations, which describe the behavior of two sides being involved in the crime (the offender and his victim), are differential. At that, the coefficients contained in them refer to the slowly changing ones.

The state of emotional stress, inevitably arising as a result of the interaction between the criminal and the victim, cannot remain unchanged endlessly long. The duration of preservation of any emotional tension level is determined, first, by the type of a person’s higher nervous activity. Also, a person’s behavior depends on his typical reactions while satisfying his relevant needs. All these factors are represented in the corresponding coefficients of the system of equations (α and β for the victim, у and g for the offender).

The equations show that there are nine basic forms of development for the «victim-offender» relationship. The three forms are symmetrical, so the practical applying these forms of relationship development is possible only in the case of using six of them, but not all nine aforementioned forms.

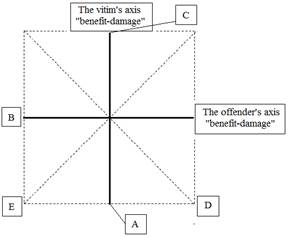

Graphical illustration of the model, presented on Figure 1, shows that while studying crimes it is possible to use only its left side, since the right side demonstrates the nonviolent forms of relations.

Therefore, the main forms of the «victim-offender» relationship in crimes are only 5:

1. «Commensal» relations - one side benefits and the other is indifferent. This form of relations represents the victim’s premeditated provocative behavior for achieving own goal (extortion, blackmail, etc.). An example of such relations can serve following. A victim of sexual violence intentionally conducts herself with a future offender in order to provoke him to begin a sexual intimacy. Herewith, the victim already knows that she will later act as a victim. In this case, one side (the offender) is indifferent to the consequences, and the second (the victim) sets a goal to derive benefit from the subsequent events (point «C» in Figure 1).

2. «Competitive» relations - both sides cause harm and damage to each other. For this form, both the offender’s aggression and energetically self-protecting defense of the victim are characteristic. As a result of that, there may be a physical destruction of one of the sides. For example, while committing a sexual violence, the offender seeks to kill the victim, and the victim by any means tries not only to avoid sexual violence, but also to destroy the offender physically. Such crimes as a robbery, murder, that is those types of crimes in which there is a direct interaction between the offender and the victim, may also be examples of such relationships (point «E» in Figure 1).

3. «Amenial» relations have two kinds of manifestation: a) One side (the offender) harms, and the other (the victim) is indifferent. These relations are characterized by the absence of any victim’s defensive action. Such a fact can be explained by a misunderstanding of the victim, by her desire to preserve a more important value than the lost one, etc. An example of this relationship is the behavior of a young victim of sexual violence, when she (the victim) does not understand the essence of what is happening (point «A» in Figure 1). b)The other side (the offender) is indifferent, and the first (the victim) harms. This type of relationship is characterized by an inadequately negative attitude of the victim in relation to the actions of the probable offender. It can be observed in persons who have already been in the role of a victim of violence. This behavior type includes, for example, the behavior of a woman when a man wants to become acquainted with her on the street. If a woman has already been subjected to violence by men, in this situation she can not only reject the signs of attention from the acquaintance, but also attack, presuming his desire for committing violence (point «B» in Figure 1).

4. «Parasitic» relationships - one side is harmful, and the second one brings to the other some benefit. This type of relationship is characterized by the victim’s fraud and her excessive credulity. A relationship in which a husband forces his wife to enter into sexual relations with another men for money may serve as an of such relationship type. In this example, the stronger side takes away the income from the weak one, while existing at the same time due to these deductibles, earnings (point «D» in Figure 1).

5. It is especially necessary to note «neutral» relations - both interacting sides are indifferent to each other. They are observed in normal relations, but while analyzing crimes this form does not really exist (this is the point of intersection of the coordinates in Figure 1).

The using of such a formalized representation of the «victim-offender» relationship makes it possible:

A) to carry out a retrospective analysis of the crime at a higher level, i. e. to define the trustworthiness of events that have already occurred. This can be done by having revealed all the factors (either in the course of special investigations or during the pre-trial investigations) that influence the development of events, which is equivalent to establishing the coefficients of the equations (1).

B) to forecast the most probable way out of the interaction between the offender and the victim by considering all possible options, taking into account already determined coefficients of the equation (1). This can be done with the help of computer technology, which will greatly enhance the effectiveness of crime prevention, especially those related to violent ones.

A rather high level of the victim’s emotional stress causes the behavior of crime victims, in particular those connected with sexual violence. Therefore, while recalling and reconstructing the events on the basis of the victim’s testimony, it is necessary to take into account the impact of emotions on the memorization being in this state (selectivity and instability of attention, untidiness of memorization, etc.), as well as the dependence of the level of voluntary regulation from emotions, limiting the perception of the situation elements, and so on. Just high emotion level during sexual violence forces the victims to conceal what has happened: neither wish to recall the details of this violence nor to speak or to publicize in any way what has occurred fact. Exactly this fact leads to considerable increasing the latency of sexual crimes, which transform in its latent form.

As shown by the studies carried out in the period of 2004-2017 in Ukraine in which the interview method was widely used (Khrystenko, 2004; Timchenko & Khrystenko, 2004), the unwillingness of the victim to communicate with anyone (including the representatives of law enforcement agencies) is due to several main reasons, namely:

1.Lowering of the victim’s social status. As paradoxically it may sound, but in Ukraine a widespread reasoning like “it’s shameful, embarrassing to be a victim of a crime” exists, however, in people’s mentality, especially this conclusion applies to sexual crimes. A lot of Ukrainians, having learned about the fact of sexual violence against someone, often accuse the very victim of the crime that she “behaved herself in a wrong way”, “did nothing to protect herself”, “teased the offender with her behavior manner”, etc. The only disclosure of the crime committing fact against a particular woman/girl very often leads to worsening an attitude towards her by colleagues on work, neighbors, acquaintances, friends and often even by relatives. Under such circumstances the victim also fears various mockeries and gibes dreading to arise a public derision.

2.The victim’s awareness of shame. The intimate sphere of a person’s life is deeply intrinsic, personal, also because this sphere cannot be usually made public and keeps certain closeness from the other persons. Therefore, sexual crimes in the vast majority of cases have a very high emotional color. This causes a victim to feel a shame when the only fact of crime committed with her becomes known for publicity.

3.The attitude transformation towards her for the worse (that the victim presumes) from the side of a loved person. The victim feels “dirty”, not worthy of her beloved person, whom the victim often deifies. This prevents herself to build any relationships with her beloved person in the future. Just here, the victim’s conviction and certainty may be added that concern her being sure that her beloved will abandon her soon after the violence.

4.The victim’s unwillingness to appear in court and during interrogations. Further per-trial and trial proceedings involve repeated interrogations of the victim, and sometimes the reproduction of the event on the scene of the crime. A simple comprehension of this fact invokes inside the victim a firm urge to persevere in own unwillingness to experience negative emotions once again during the forced recall-reproduction of all the crime details.

We are convinced that the problem of investigating crimes against the person’s sexual freedom and sexual inviolability, viz, in a situation when the victim does not want to talk about violence committed against her, can be partially solved by the method of mathematical modeling. While studying just the latent part of the crime victims, in particular sexual violence, the method of transformed interview is proposed by us as the most effective.

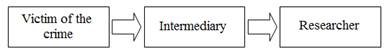

The essence of the transformed interview method lies in the fact, which the required information can be obtained not directly from the crime victim herself, but from her friends, relatives, acquaintances, i. e. from the people who knows the details of what had happened. Despite some distortion of information, this approach makes it possible to obtain much more data than a person-to-person communication with the victim directly.

Method

Participants

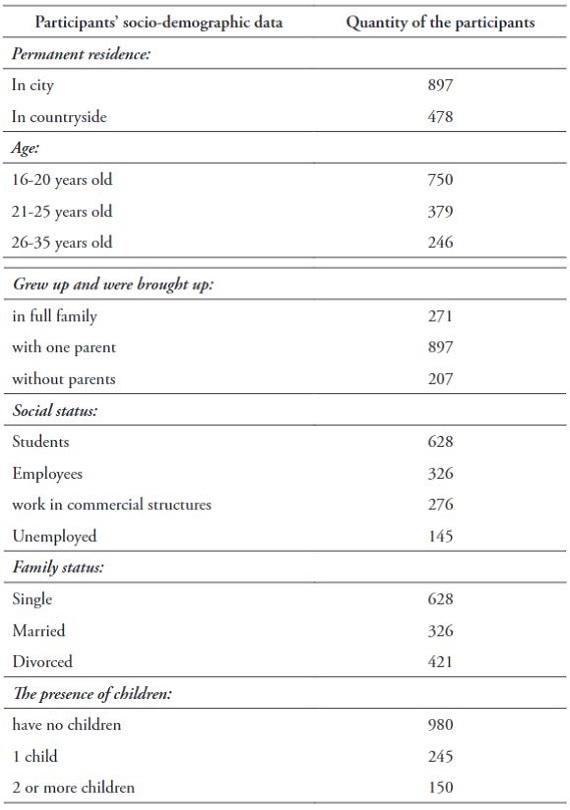

This research involved 2570 participants: women of 16-35 years old with the different social status. Among the interviewed participants, there were identified the ones having the relatives and friends who had been sexually assaulted (1375 persons). Exactly from them the information about sexual abuse was received. The remaining 1195 women had no relatives, friends or close acquaintances who would have been sexually abused.

The socio-demographic data of the participants (women who have experienced sexual abuse) are given in Table 1. All study participants were contacted personally. Telephone, e-mail, regular mail were not used for contacting the 1375 sexual victims interviewed. Written letter of consent to participate in the study was not asked, since in 100 percent of cases such victims always previously refused to give any written statements (we emphasize that our respondents were the latent, i.e. hidden, victims of sexual crimes).

Measures

We developed the context of structured interview especially for this study conducted during personal contact. The following is the contextual structure of the interview, during which the researchers tried to find out information about the sexual crime that this woman was a victim of:

1. Place of sexual abuse.

2. The persons who participated in the violence.

3. Exact facts that had happened (details of violence).

4. Victim’s behavior before the violence (whether a possible provocation of violence by the victim herself had place).

5. The behavior of the victim at the time of the commission of violence (resisted or not, whether the victim tried to neutralize the abuser, whether she used any available means).

6. The behavior of the victim after the end of violence (contacting law enforcement agencies, the story of the incident to relatives or friends).

7. The behavior of the victim a few days after the end of the violence (the victim’s attempt to take revenge without addressing the law enforcement authorities).

8. The reasons for which the victim concealed the fact of sexual violence.

9. The willingness of the victim in the future to help other victims of sexual violence.

Procedure and Data analysis

Processing the data was carried out by content analysis. In summarizing the data used statistical mathematical methods.

At the beginning of the interview, a psychological contact was made with the victim. Then the researchers (certified psychologists) tried to get detailed information about the fact of sexual violence. Depending on the situation, the interview questions may be asked not in the aforementioned order, but in accordance with the necessity during the interview.

At the next stage of the study, the information was checked by means of the interviews with the victims of sexual violence themselves. The information on the same crime received from the mediator and from the victim herself had a credibility of 75-80% (the results were obtained by conducting a content-analysis of the information received directly from the victim of the crime and from the intermediary (the victim’s friend or relative).

To assess the reliability of the received information, the expert evaluation method was used (the experts in the field of criminology and psychologists were involved). The mathematical methods of data comparing, which are usually used to compare the results of various psychological methods, were not applied in this case, since the data obtained from the victim of the crime were not formalized.

Results and Discussion

We carried out two stages of the study (theoretical modeling and empirical confirmation) to establish the regularity of reducing the reliability of information, depending on the number of transfer links.

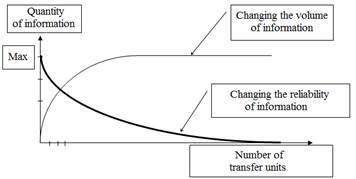

During the first (theoretical) stage it was found that with the increase of intermediaries during the information transmission, its reliability [i.e., of the information] is reduced, and the total volume is increased. Based on the conclusions of the information theory and probability theory, it should be concluded that the reliability of information, depending on the number of intermediaries, varies according to the regularity described by the formula (2):

where: D - reliability of information; e - the base of the natural logarithm; k -coefficient of distortion of the information.

The coefficient k is different for different social groups, which was an obstacle in the application of this method. The correct application of this method involves, first of all, finding the corresponding coefficient k. The graphic representation of this dependence is shown in Figure 2.

The real use of this method is possible only after setting the coefficient k, which is equivalent to determining the number of transfer links for the social environment under study.

The search for this coefficient with the maximum volume of reliable information reduces to solving a standard mathematical problem when investigating these dependencies (Figure 2).

Investigating the crimes against the person’s sexual freedom, sexual inviolability and criminological research using this method can be carried out by obtaining the necessary information with the help of one, and in some cases, two mediators. The coefficient k or the degree of information distortion in the overwhelming majority of cases is established empirically for the investigated medium and depends on the proximity of the crime victim and the mediator.

During the process of the information transfer, the factor of belonging both the mediators and the victim to one particular social stratum is very important. However, one should bear in mind that if the mediator has recently become part of the social stratum of the victim, this can lead to a significant distortion of the information, since the stereotypes of the mediator and the victim formed in different social environments, and they will interpret the same fact differently.

As transmitting links, close relatives, friends, etc., that is, those who know the details of what happened, can act.

With the participation of more than two intermediaries in the transfer of information, there is a distortion of the data, leading to a very strong change in them. Each additional intermediary understands something in his own way, and on the basis of his understanding he supplements something else. This leads to an unjustified increase in the total volume of information and, correspondingly, to the falling in its reliability. That is, no more than two intermediaries can obtain the information with a sufficient share of its reliability.

The opposite phenomenon - the reduction of information - is often observed in the victim’s narration, which very often seeks to maintain his anonymity, resorts either to a conscious distortion of the events that occurred, or to the passing over in silence of any facts, which is identical, in fact, to obtaining information according to the scheme (Figure 3).

The main advantages of the method of transformed interviews are as follows:

Ability to obtain the in formation that can not be found in the other ways.

Possibility for the victim under investigation to remain anonymous guarantees more truthful answers.

Possibility of obtaining information about both the object of research (about the victim) and the social environment that generated the victimization.

Independence of the method from the social-cultural characteristics of the victim’s environment.

The main disadvantages of the method of transformed interviews are the following:

Impossibility of conducting classical psycho-diagnostic techniques, since the victim herself is not physically accessible.

Some information distortion because of the presence of a transfer link in obtaining information.

We have used this method during the second stage of our research while studying latent victims of sexual violence (Khrystenko, 2004). With the subsequent application of this method (during the investigations of 2016-2017 by means of a content analysis of the information received from the mediator and the victim) it was found that the greatest reliability with the maximum amount of information for the social environment under study is observed with one intermediate link while obtaining the information. Namely, a frank story, an explicit reproduction of rape, for example, is possible according to the scheme shown in Figure 3, but at only one condition that the victim and the intermediary belong to the same social stratum.

The application of the transformed interview method with the subsequent content-analysis of the received information was widely used by us in Ukraine in the further research, conducted in 2017-2018 in the cities of Kharkov, Kiev, Dnepropetrovsk. The authors of this article followed the ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct as recommended by the APA. This study was conducted in accordance with the Ethics Experts directives of the Laboratory of Extreme and Crisis Psychology of the Kharkov National University of Civil Protection of Ukraine, Ukraine, and the research project was previously approved under the protocol number 6/2-2017.

In addition, the receipt of data on the details of the sexual offense through one mediator enabled the law enforcement agencies to clarify the qualification of the crime. In particular, thanks to the use of the method of the transformed interview based on the mathematical modeling method, in 2017 out of 127 criminal cases on sexual crimes opened by the police in the city of Kharkiv in the period from 2012 to 2016, 15 criminal cases were revised and the verdict wordings against a suspect in the commission of a crime against the person’s sexual freedom and sexual inviolability were changed.

Thus, the investigations conducted in 2016-2017 showed that sometimes the information about crimes against the person’s sexual freedom and sexual inviolability can be obtained with a high degree of reliability not from the victim, but from her closest associates and surroundings. Sometimes it is advisable to get the primary information from the nearest environment, and the more refined already - exactly from the victim. If the victim of the crime knows that the information about the violence against her has become the property of someone else, this is the impetus to the fact that the victim decides to communicate with the law enforcement agencies and begins to testify at the preliminary investigation and in court.

Conclusions

Hence, the use of the mathematical modeling method in the study of crimes against the Personality’s sexual freedom and the sexual inviolability has both a theoretical and an applied nature. The use of the transformed interviews method makes it possible to reduce the latency of crimes against the sexual freedom of the individual. Also, this method provides an opportunity to obtain more detailed information about the sexual violence, and sometimes about the fact of its commission as well. These methods (the mathematical modeling method and the method of transformed interviews) are really effective tools by means of which it is possible to supplement the data on the behavior of the offender and his victim in a significant way, to reduce the latency of the majority of crimes, to avoid as much as possible the incorrect formulations of the suspect’s status in pre-trial investigation and to exclude the probability of erroneous judicial verdicts.