Attachment is a specific and discriminative bond that is co-constructed through the interactions between two individuals. It is characterized by a tendency to seek and maintain closeness to a specific figure, particularly under stress (Salinas-Quiroz & Posada, 2015). It has been stated that “[a]ttachment theory provides a strong framework for understanding associations between the quality of primary caregiver-child relationships and mental and psychological well-being over time” (Pascuzzo et al., 2015, p. 3). Adults co-construct these bonds with peers and/or partners, where both members of the dyad work as a security base for the other in different moments (Hazan & Shaver, 1987, 1994). Bartholomew and Horowitz (1991) proposed an adult attachment model based on the interaction between the perception people have of themselves and of others, which will influence interpersonal relationships, the expression of emotions, emotion regulation strategies (Belsky, 2002; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019; Uytun et al., 2013), conflict resolution strategies and the probability to experiment positive emotions (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991). If both images are polarized, four combinations of attachment can be conceptualized: secure, preoccupied/anxious, dismissive-avoidant, and fearful-avoidant (Collins, 1996; Feeney & Noller, 1990, 1991; Hazan & Shaver, 1987, 1994).

Attachment and emotion regulation

Based on attachment theory, the parent-child affective bond influences the development of emotion regulation strategies thought to be important for later adult adaptation (Pascuzzo et al., 2015). Further, even though attachment theory concerns itself mainly with interpersonal and developmental issues, it can also be seen as an emotion regulation theory (Carrère & Bowie, 2012; Fernandes et al., 2019; Malik et al., 2015; Mikulincer & Florian, 2007; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019; Nichols et al., 2019; Roque & Veríssimo, 2011; Schore & Schore, 2008; Stevens, 2014). In fact “secure attachments help a person survive temporary bouts of negative emotion and how different forms of insecurity interfere with effective emotion regulation, social adjustment, and mental health” (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019, p. 3).

While people with a secure attachment style utilize strategies that minimize stress and promote positive emotions, those with an insecure attachment employ strategies of emotional regulation that emphasize negative emotions and emotional repression (Kobak et al., 1993; Kobak & Sceery, 1988; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019; Mikulincer et al., 2003).

Emotional regulation refers to the extrinsic and intrinsic processes responsible for monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional reactions through which we seek to increase, maintain or lower one or more components of them, be it in a conscious or unconscious way (Gross, 2001; Thompson, 1994). This involves changes on the emotional response such as the type of emotions that people have, when they have them and how they experiment and express them (Gross, 2015). Based on attachment theory, individuals adopt specific emotion regulation strategies to accomplish their goal of dealing with distress (Pascuzzo et al., 2015).

These ideas support why people’s decision making about the specific implementation of these strategies is important (Gross, 2001, 2015; Gyurak et al., 2011; Koole, 2009; Prosen & Vitulić, 2014). The most common strategies are cognitive reevaluation and emotional suppression (Hu et al., 2014). Cognitive reevaluation is a strategy focused on the antecedents that includes the reinterpretation of an event associated to an emotion aimed at decreasing its emotional impact (Ochsner & Gross, 2008). This last one is an adaptive strategy that has a favorable impact on mental health -self-esteem and life satisfaction- (Gross & John, 2003). In the case of emotional suppression, it is a strategy focused on responses, which means inhibiting the observable expression of the emotional experience in an active way, and it is associated with poor mental health (Gross, 2001; John & Gross, 2004).

Attachment styles, emotion regulation and mental health

Bakermans-Kranenburg and van Ijzendoorn (2009), found evidence that clinical and non-clinical samples have different distribution in their attachment styles; the firsts show more insecure and unresolved attachment representations than the non-clinical samples. Moreover, based on different samples and studies, it is expected that in general population, the attachment styles can be observed in their secure form in 58% of the cases, in 23% in its insecure-dismissing form and in 19% of the cases in its insecure-preoccupied form.

Secure people are autonomous but at the same time search for emotional help in their attachment figures when they need it (Allen et al., 2007; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019), they tend to openly discuss problems and solve conflicts instead of avioiding them (Belsky, 2002; Feeney & Noller, 1990; Fleming, 2008; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2012, 2019). Securely attached individuals tend to have more positive expectations about their ability to regulate negative moods and to resolve life-problems when compared to insecurely attached individuals (Nielsen et al., 2017). The first attachment style is considered a protective factor against psychopathology, since it has been associated to a lower prevalence of depression (Paradiso et al., 2012; Surcinelli et al., 2010), anxiety (Erozkan, 2011; Reynolds et al., 2014), personality disorders (Kim et al., 2014; Levy et al., 2015), criminal activities (Allen et al., 2002), and non-substance-related addictions (Estévez et al., 2017).

There is accumulating evidence that people encoring high on attachment anxiety or avoidance have serious difficulties in identifying and describing emotions (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019). Moreover, people with a preoccupied/anxious attachment style develop anxiety and feelings of personal inefficacy, not feeling loved enough and believing that they have no control over their environment (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991). They tend to focus on their own anguish, rummaging negative thoughts and adopting coping strategies centered on the emotions that worsen their suffering instead of lowering it (Reynolds et al., 2014; Stevens, 2014). Added to this, the people have a higher access to painful memories about what other people do (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019; Mikulincer et al., 2003; Shaver et al., 2000). This preoccupied attachment is considered a nonspecific risk factor for developing psychopathology (Nielsen et al., 2017) since it has been associated to a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms (Cole-Detke & Kobak, 1996; Cooley et al., 2010; Malik et al., 2015; Paradiso et al., 2012; Permuy et al., 2010), suicidal thoughts (Adam et al., 1996), anxiety (Erozkan, 2011), alexithymia (Besharat & Shahidi, 2014), and personality disorders (Levy et al., 2015).

People with a dismissive-avoidant attachment style have a high achievement orientation and their emotional regulation strategy consists of the denial of affective needs and on emotional self-sufficiency, trying to be invulnerable to rejection and negative feelings (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991; Brennan et al., 1998; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019). Despite the fact that the findings for attachment avoidance are less conclusive (Nielsen et al., 2017), this attachment style has been related to behavior disorders, substance abuse, criminal behaviors, alexithymia and schizoid traits (Allen et al., 2007; Besharat & Shahidi, 2014; Lyddon & Sherry, 2001; Rosenstein & Horowitz, 1996; Sherry et al., 2007).

For people with a fearful-avoidant attachment style, fear of rejection stops them from starting intimate relationships or friendships, keeping a minimum social network, and thus implementing emotional suppression as an emotional regulation strategy (Cassidy, 1994). Furthermore, it is unlikely for them to share information about themselves, showing issues to handle conflict (Cooley et al., 2010). This attachment style has been associated to higher levels of depression and anxiety (Camps-Pons et al., 2014; Erozkan, 2011), as well as personality disorders (Levy et al., 2015) and psychosis (Korver-Nieberg et al., 2014).

On social adjustment: need for social approval/social desirability

The Need for Social Approval (NSA) is rooted in the Social Desirability construct (SD). SD is a very popular concept that refers to a tendency to respond to certain situations in a socially acceptable way (Richman et al., 1999). For some authors, it is considered a source of bias in self report measures (Mueller-Hanson et al., 2003; Paulhus, 1981, 2002; Rosse et al., 1988; Tatman & Kreamer, 2014; Watson et al., 2006), despite the fact that the evidence to support this claim is inconsistent (Marlowe et al., 1964; Ones et al., 1996). Based on empirical evidence, it has been suggested that SD is a stable trait, linked to an intrinsic NSA (Barger, 2002; Domínguez Espinosa et al., 2012; Marlowe et al., 1964; McCrae & Costa, 1983; Smith & Ellingson, 2002; Uziel, 2010). SD has shown stability for over five decades and more than 60 cultural settings; furthermore, it is linked to different psychological and sociological domains (Domínguez Espinosa et al., 2012; Domínguez Espinosa et al., 2018; Domínguez Espinosa & Méndez García, 2014; Domínguez Espinosa & Van de Vijver, 2019).

NSA has been positively associated to psychological wellbeing (Acosta-Canales & Domínguez Espinosa, 2012; Brajša-Žganec et al., 2011), assertiveness (Flores Galaz et al., 2014), self-control (Orozco Parra et al., 2014), and negatively associated to suicidal ideation, psychopathology, and with antisocial personality disorder (Ruiz & Preti, 2008; Padrós-Blázquez et al., 2018; Preti & Miotto, 2011). Last, but not least important, the construct has been associated with overclaiming scores (a type of objective self-report bias) with no significative results (Ruiz Paniagua et al., 2014).

Following a vast empirical evidence, it is suggested that the NSA is composed of two components: One positive and one negative dimensions (Messick, 1960). The first dimension comprises behaviors that are positive or desirable (e.g. forgiveness, kindness, unconditional love, etc.). The second dimension comprises behaviors that are negative or undesirable (e.g. bribe someone, lying, speak ill of a fiend, etc.). Usually, these two dimensions are interpreted in terms of attribution of positive attributes and the denial of negative ones (Paulhus, 1998, 2002; Ramanaiah & Martin, 1980). The denial assumption is straight forward interpreted as lying, and this is the reason why is usually used as a measure of invalidity of a test. However, if we recalled those seminal words from Meelth and Hathaway (1946, p. 560): “We may distinguish two direction in this test-taking attitude: the tendency to be defensive or to put oneself in a too favorable light, and the opposed tendency to be overly honest and self-critical (plus-getting)”, we can assume that the second interpretation can be as valid as the first one. In this sense, we can re-interpret the NSA second dimension as the acceptance of error. This interpretation have sufficient empirical support (Domínguez Espinosa & van de Vijver, 2014; Rogers et al., 2014) and can explain why the score are consistent with measure of honesty, self-esteem and conscientiousness, meanwhile others objective distortion measures don’t show the same pattern (Domínguez Espinosa et al., 2012). Finally, another theoretical support comes from the literature about perfectionism in which it is stablished the connection between the non-disclosure or non-display of imperfection -in other words acceptance of error- with suicidal risk (Roxborough et al., 2012), insecure attachment (Chen et al., 2012), helplessness (Filippello et al., 2017) ,and depression (Carrera & Wei, 2017; Wei et al., 2006) that also in the same line of argument that those results from the social desirability literature.

Children with a high NSA have a higher acceptance and it is less likely for them to relate to others in an aggressive manner, to be excluded from their group, or to show social hopelessness (Rudolph & Bohn, 2014; Rudolph et al., 2005). The intrinsic NSA may be an unstudied element that comes into play in secure-base relationships, since attachment bonds are co-constructed, and the child will find a safety heaven on and will explore the environment depending on both caregiver’ sensitivity and approval. Uziel (2010) mentioned how individual differences on SD are associated with the capacity to construct lasting and satisfactory marital relationships, as well as create and maintain friendships, and be successfully integrated to society. This idea supports the notion that SD works as a motivator that leads the behavior of people and facilitates social adaptation. At the same time, SD is related to the ability to moderate negative emotions and have a higher orientation towards optimism and constructive thoughts (Park et al., 1997). The behavioral patterns of people with high SD seem to be highly adaptable; this is the reason why it be a self-regulation ability (Uziel, 2010).

The association between NSA and MH can be partly explained by the fact that the first works as an incentive for people to have behaviors oriented towards looking for the acceptance of others. This allows the creation of healthy interpersonal relations and with this, a greater number of positive stimuli, which would in turn generate higher psychological wellbeing. NSA besides being positively correlated with MH, is also negatively correlated with psychological distress (Smith et al., 2007), as well as depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts, personality disorders and psychiatric symptoms, suggesting that NSA could be a protective factor against mental illness (Clark et al., 1998; Cramer, 2000; Davenport et al., 2012; Preti & Miotto, 2011).

It must be remembered that according to Bowlby (Bowlby, 1973, 1979, 1988) the sense of attachment security (confidence that one is competent/lovable and that others will be responsive and supportive when needed) is not only a resilience resource in times of need, but also a building block of mental health and social adjustment (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019) where the NSA becomes a mechanism for adaptation and co-construction of close interpersonal relationships.

Based on the literature review, the aim of this study was to assess the relationship between attachment styles, emotional regulation, need for social approval/social desirability and mental health. Furthermore, the following hypotheses were raised:

1) The four attachment styles will have differences in MH indicators, where securely attached individuals will have the highest scores on psychological wellbeing.

2) The four attachment styles will use different emotional regulation strategies. Specifically, secure and preoccupied/anxious participants will make use of cognitive evaluation while dismissive-avoidant and fearful-avoidant individuals will prefer emotional suppression.

3) The four attachment styles will have differences in both positive and negative NSA. Securely and preoccupied attached participants will have higher scores on Positive-NSA, on the other hand, dismissive and fearfully attached individuals will have higher scores on Negative-NSA.

4) NSA will be positively associated with MH indicators: Positive-NSA with psychological well-being and Negative-NSA with psychological distress.

-

5) NSA and Emotional Regulation will mediate the relation between attachment styles and MH indicators, where:

a. The Preoccupied, Dismissive and Fearful Attachment Styles will contribute negatively higher to Wellbeing, and positively higher to Distress, when compared to the Secure Attachment Style.

b. The Positive and Negative Need for Social Approval and the Emotional Regulation will mediate significantly the relation between the Attachment Styles and Mental Health

c. The Cognitive Reevaluation and the Emotion Suppression strategies of Emotional Regulation will mediate significantly the relation between the Attachment Styles and Mental Health.

Method

A cross-sectional quantitative field study was performed.

Participants

Using accidental and snowball sampling, 469 individuals between the ages of 18 and 69 years old (M= 35.9; SD = 12.48) participated, who were recruited via social networks. 378 were females (74.86%) and 127 males (25.14%), from 28/32 states from Mexico; 43% were single, 39% married, 16% divorced or separated, and 2% widowed. 55% said to have up to undergraduate studies, 24% up to high school or community college, 14% up to postgraduate studies, 6% up to secondary school and 1% up to elementary school studies.

Measurement

Mental Health Inventory MHI-38 (Weinstein et al., 1989). It is a self-report questionnaire comprising 38 items distributed in five dimensions: anxiety (10 items), depression (5 items), loss of emotional/behavioral control (9 items), positive affect (11 items), and emotional bonds (3 items). At the same time, these subscales or dimensions allow the evaluation of the psychological wellbeing or distress. The responses to each item are given in an ordinal scale of five or six options. The MHI-38 has reported a Cronbach coefficient of α=.83 to α=.96 (Veit & Ware, 1983).

Revised Adult Attachment Scale (Collins, 1996). This self-report scale consists of 18 items distributed into three subscales (each one of 6 items): 1) Closeness with others which assesses the extent to which a person is comfortable with closeness and intimacy (i.e. “I find it relatively easy to get close to people”), 2) Depending on others measures the extent to which a person feel that s/he can rely on others to be available when needed (i.e. “I know that people will be there when I need them”), and 3) Anxiety on their relationships which evaluate the extent to which a person is worried about being rejected or unloved (i.e. “When I show my feelings for others, I’m afraid they will not feel the same about me”). Each response is graded on a scale of 5 points. Based on these subscales, the attachment style can be categorized into one of the four categories described by Bartholomew & Horowitz (1991).

In order to sort the participants into one of the four attachment styles, the total score for each subscale was calculated for every individual. A composite score i.e. Close-Depend, was created by summarizing the total score of Closeness with others and Depending on others scales. This composite score (Close-Depend) was used with the Anxiety on their relationships total scale score (i.e. Anxiety score) as follows: If the Close-Depend score is greater than 3 and the Anxiety score is less than 3, then the person was classified in the Secure attachment style; if the Close-Depend score is greater than 3 and the Anxiety score is greater than 3, then the participant was classified in the Preoccupied/Anxious attachment style; if the Close-Depend score is less than 3 and the Anxiety score is less than 3, then the individual was classified in the Dismissive-Avoidant attachment style; finally, if the Close-Depend score is less than 3 and the Anxiety score is greater than 3, then the person was classified in the Fearful-Avoidant attachment style. The reliability of the three scales has been previously reported: α=.67 for Closeness with others, α=.75 for Depending on others and α=.72 for Anxiety on their relationships.

Emotional Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, 2003). It is a self-report instrument consisting of 10 items graded on a 5-point scale, which evaluates two emotional regulation styles: cognitive reevaluation (i.e. “I control my emotions by changing the way I think about the situation I’m in”) and emotional suppression (i.e. “When I am feeling negative emotions, I make sure not to express them”). Regarding the reliability of the scale, a α=.75 has been reported for emotional suppression, and a α=.79 for cognitive reevaluation (Cabello et al., 2013).

Indigenous Social Desirability Scale (Domínguez Espinosa & van de Vijver, 2014). It consists of 14 items in a 5-point Likert type scale. It measures two dimensions: Positive Need for Social Approval, consisting of 6 items (i.e. “I am kind to everyone, no matter the way they are”); and Negative Need for Approval consisting of 8 items (i.e. “I have avoided giving back something that does not belong to me pretending I have forgotten”). The reliability shows internal consistency indexes for the positive dimension of α=.74, and α=.71 for the negative dimension.

Procedure

The application of these instruments was done online using the Limesurvey platform. Recruitment of participants was carried out through announcements on social networks. To encourage participation, potential participants were invited to endorse the survey anonymously and in a voluntary basis. The invitation explicitly indicated that if they completed the test battery with accurate responses, they would be given general information regards their performance in the areas of personality, self-esteem, wellbeing, and mental health. The feedback given to each participant at the end of the survey had never intended to substitute any professional screening and they were warned of not taking the feedback in substitution of a specialized diagnostic or evaluation. The feedback showed the total score obtained in each subscale with a frugal description of the results. In certain cases where participants scored particularly low (e.g. self-esteem) a general recommendation to seek professional counseling appeared. Upon completion, some participants shared the link of the survey with people they known, generating a snowball effect.

The authors of this paper administered the platform and performed data analysis. All three authors are postgraduate academics and researchers from the Ibero-American University/National Pedagogic University. The data was processed with the SPSS statistical package version 25.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analysis of central tendency and dispersion were performed, as well as parametric bivariate correlations. In addition, a one-way analysis of variance was performed to compare the four attachment styles and their effect on each of the other psychological variables. An integrated model to understand the influence of the four attachments styles and the potential mediating role of the NSA and emotional regulation dimensions over MH (i.e., wellbeing and distress), was proposed.

Ethical Considerations

The National Council of Science and Technology granted the ethical endorsement of the project. Likewise, it was registered as part of the activities of the Psychology Department with the endorsement of the Academic Council: its members supervised that the ethical guidelines of the Ibero-American University were complied with. As it was an online project, participants were asked for their informed consent by this means. In it, voluntary and anonymous participation was ensured. Participants had the option to stop responding whenever they want. They were only asked for their sex and age. The protection of the information was the responsibility of the second and third author as part of their personal files, to which only they access.

Results

In accordance with Collins’s classification system (1996), from the total sample of 469 participants, 47% of participants were classified in the secure attachment group (n=222), 13% in the preoccupied/anxious group (n=62), 16% in the dismissive-avoidant group (n=73) and the 24% in the fearful-avoidant group (n=112).

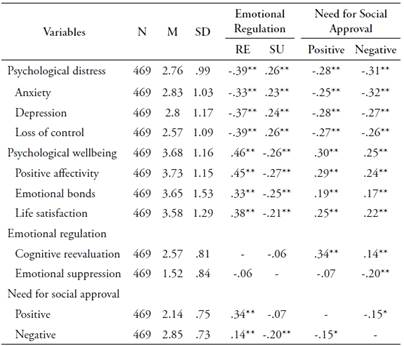

Pearson bivariate correlation analysis were carried between all the continues variables. As it can be observed on Table 1, all the correlations were significant (p<.05), except for Emotional Suppression that did not correlate with Positive-NSA.

The different indicators of psychological distress (anxiety, depression, and loss of control) correlated positively, moderately and significantly with emotional suppression, on the other hand, as expected for our hypothesis, NSA scores were both positive and negative correlated negatively, low and significantly with cognitive reevaluation.

In the same way, it can be observed that the association between psychological wellbeing with its respective indicators (positive affect, emotional bonds and satisfaction with life) is positive, moderate and significant with cognitive reevaluation; simultaneously, it correlates moderately with positive and negative NSA, while the associations with emotional suppression are negative, low and significant.

Table 1 Descriptive statistics and correlation between Mental Health Indicators and Emotional Regulation and Need for Social Approval subscales.

Note: The subscales scores for the attachment style scales are not displayed in the table, as they are not used as continuous variables since the aim of these measures is to sort participants into the four attachments styles proposed byCollins (1996) afterBartholomew & Horowitz (1991). RE=Cognitive reevaluation; SU= Emotional suppression. **p<.001, *p<.05

Both positive and negative NSA are associated significantly with cognitive reevaluation. In the case of emotional suppression, as indicated before, it is only associated negatively and significantly with negative NSA.

To analyze the different attachment styles, a variance analysis of one factor was conducted (ANOVA) (see Table 2). Likewise, the data shows a significant difference in all the variables related to the attachment style, even though the magnitude of the difference -effect size- varies. Negative affect shows the greater effect, particularly the loss of control subscale (F= 57.21), while the most modest effect can be observed in positive NSA (F= 7.96).

According to the first hypothesis, those participants classified in the secure attachment groups score significantly lower in all three psychological distress measures (anxiety, depression, and loss of control), and significantly higher in the psychological wellbeing measures when compared to the remaining three attachment styles.

As regards to the second hypothesis, cognitive reevaluation scores are significantly higher and the emotional suppression scores are significantly lower for the secure attachment group.

The third hypothesis was also supported, since the secure and preoccupied-anxious individuals scored significantly higher in the NSA positive dimension when compared to the dismissive-avoidant and fearful-avoidant participants. For the NSA negative dimension, the secure attachment group scored the highest, followed by the dismissive-avoidant, then the preoccupied and finally (i.e., the lowest) the fearful-avoidant group.

People with secure attachment show the highest scores on Positive-NSA and Negative-NSA, cognitive reevaluation, emotional bonds, satisfaction with life, positive affect, and psychological well-being. On the other hand, individuals classified as fearful show the lowest scores on Positive and Negative NSA, as well as cognitive reevaluation, but the highest scores on emotional suppression, anxiety, depression, loss of control and psychological distress.

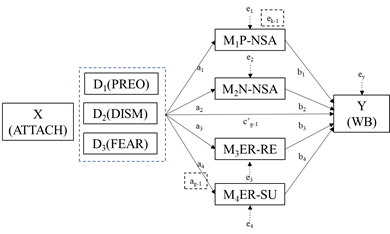

Finally, we conducted two parallel multiple mediation models with multicategorical antecedent variable to verify if the Positive and Negative NSA as well as the Reevaluation and Suppression strategies of Emotional Regulation mediate the effect of Attachment Styles on Wellbeing and Distress. Given space restrictions, only the diagram corresponding to Wellbeing is presented (see Figure 1).

Table 2 One-factor variance analysis according to the four Attachment styles with post-hoc effects.

Note: SEC=Secure attachment; PREO= Preoccupied/anxious attachment; DISM=Dismissiveavoidant attachment; FEAR=Fearful-avoidant attachment. Scheffé post-hoc test (p<.05)

Note: ATTACH: Attachment styles; PREO: Preoccupied/anxious style; DISM: Dismissive-avoidant style; FEAR: Fearful-avoidant style; P-NSA: Positive need for social approval; N-NSA: Negative need for social approval; ER-RE: Cognitive reevaluation; ER-SU: Emotional suppression. X represent the antecedent variable, M represent a mediator variable, and Y the consequent variable. a’s represent the proposed mediators on X; b’s represent the Y regressed on mediators; c’s is the direct effect on Y between two participants experience the same level of a M, but differ on the type of their attachment style (X). Some direct and indirect effects from the different categories of the antecedent variable on the mediators and over the consequent variable are omitted in the diagram for readability reasons. The Secure attachment style is the reference category in all the analyses.

Figure 1 Statistical diagram representing the Parallel Multiple Mediator Model with the Multicategorical Attachment Styles as the antecedent variable.

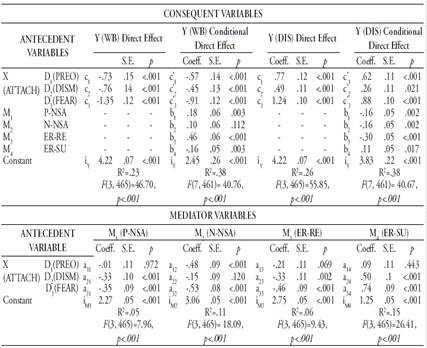

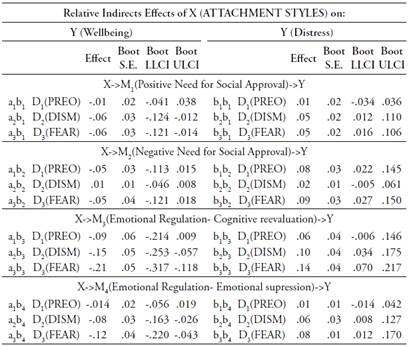

The mediation models were conducted with the free available macro PROCESS (Hayes, 2018) built on SPSS coding and using Ordinary Least Squares path analysis. The summary of the estimations is displayed in Table 3. The program calculated 95% bootstrap confidence intervals for the relative indirect effects of every attachment style when compared with the secure group (Table 4). The regression equations representing the model are available as an Appendix.

Table 3 Model Summary Information for the Parallel Multiple Mediator Model of Wellbeing and Distress.

Note: WB= Wellbeing; DISS= Distress; PREO= Preoccupied/anxious attachment; DISM=Dismissive-avoidant atachment; FEAR=Fearful-avoidant attachment. P-NSA= Positive need for social approval; N-NSA= Negative need for social approval; RE=Cognitive reevaluation; SU= Emotional suppression. Secure attachment is the reference category

Table 4 Model Summary Information of the Relative Indirect Effects for the Parallel Multiple Mediator Model of Wellbeing and Distress.

Note: PREO= Preoccupied/anxious attachment; DISM=Dismissive-avoidant attachment; FEAR=Fearfulavoidant attachment. Secure attachment is the reference category.

From the Parallel Mediation Models (Table 3), we proved that secure attachment predicts positively Wellbeing and negatively Distress. Preoccupied attachment style predicts negatively higher effect of negative NSA (a12= -.48) when compared to secure attachment. Dismissive attachment predicts negatively higher NSA (a21= -.33), cognitive reevaluation (a23= -.33), and positively higher emotional suppression (a24= .50) when compared to secure attachment. Fearful attachment predicts negatively significative higher levels on positive NSA (a31= -.35), negative NSA (a32= -.53), cognitive reevaluation (a33= -.46), and positively higher levels of emotional suppression (a34= .74) when compared to secure attachment. Participants with higher levels of positive NSA (b1= .18), cognitive reevaluation (b3= .46), and lesser levels of emotional suppression (b4= -.16) expressed higher levels of wellbeing, keeping secure attachment constant. Dismissive attachment styles through positive NSA (a2b1= -.06), cognitive reevaluation (a2b2= -.15), and emotional suppression (a2b3= -.08) were entirely above cero; fearful attachment though positive NSA, cognitive reevaluation, and emotional suppression were also above cero (a3b1= -.06, a2b3= -.21, a3b3= -.12 respectively). Therefore, the hypothesis that positive NSA, cognitive reevaluation, and emotional suppression mediate the effect of attachment styles on wellbeing was supported.

When predicting distress, participants with lesser levels of positive NSA (b1= -.16), negative NSA (b2=-.16), cognitive reevaluation (b3= -.30), and higher levels of emotional suppression (b4= .11) expressed higher levels of distress, keeping secure attachment constant.

As in the previous model, the bootstrap confident intervals were calculated on 5,000 bootstrap sample. Dismissive attachment indirect effects through positive NSA (b2b1 =.05), cognitive reevaluation (b2b3= .10), and emotional suppression (b2b4= .06) were entirely above cero; the same trend was followed by fearful attachment though positive NSA (b3b1= .05), negative NSA (b3b2= .09), cognitive reevaluation (b3b3= .14), and emotional suppression (b3b4= .08). Consequently, the hypothesis that NSA, negative NSA, cognitive reevaluation, and emotional suppression mediate the effect of attachment styles on distress was also supported.

Discussion

Although it is known that there is a relationship between the attachment style, emotional regulation and mental health (e.g. Carrère & Bowie, 2012; Fernandes et al., 2019; Kobak et al., 1993; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019; Mikulincer et al., 2003; Nichols et al., 2019; Pascuzzo et al., 2015; Roque & Veríssimo, 2011; Schore & Schore, 2008), and that need for social approval is associated with mental health (e.g. Acosta-Canales & Domínguez Espinosa, 2012; Miotto & Preti, 2008), the relationship between attachment styles and need for social approval is not well stablished even if it is a natural conceptual link between the two concepts. The main goal of the present study was to shed light in the link between these four variables.

To begin with, it was found that 47% of the participants were classified as secure, while 53% were classified within the three insecure attachment styles; these results are in line with what Bakermans-Kranenburg and van Ijzendoorn (2009) reported in their study with U.S. Samples. This last percentage represents a large amount of people who may be suffering emotional distress in their interpersonal relationships. Accordingly, it is important to study how the attachment styles through childhood affect adulthood and the consequences the former have on mental health. The insecure attachment styles (preoccupied/anxious, dismissive-avoidant and fearful-avoidant) are associated with psychological distress and tend to use more emotional suppression (Cassidy, 1994). People with a secure attachment style showed higher psychological wellbeing scores, and use cognitive reevaluation more (Gross & John, 2003).

Moreover, one of the factors influenced by the attachment style is the way people interact with others, reason behind analyzing the role of NSA on MH. As expected, NSA was negatively associated with the negative indicators of negative MH (Miotto & Preti, 2008; Preti & Miotto, 2011), and in a positive way with the positive indicators (Acosta-Canales & Domínguez Espinosa, 2014; Brajša-Žganec et al., 2011). This means that when a person is looking for the approval of other people, it may help them achieve higher psychological wellbeing and would lower the probability of them developing a form of psychopathology. From this, it can be pointed that NSA, which has been constantly considered a negative characteristic, it really has a positive effect on individuals’ psychological health and social adjustment.

The fact that NSA is higher in participants with secure attachment could mean that people are capable to co-construct secure base relationships, showing interest to find approval, which highlights how the intrinsic NSA may come into play in attachment bonds. All these, more than an anxiety source, provide motivation to get close to others, to deploy a series of behaviors to facilitate such acceptance and provide positive experiences. The aforementioned generates a network of support that functions as a protective factor against emotional distress. However, NSA is also high in people with a preoccupied/anxious attachment style, and this style is linked to psychological distress, although with less intensity than with the fearful-avoidant attachment. It is important to consider that with the preoccupied/anxious attachment style, there is a high need of approval, which could make the person get close to others and establish emotional bonds. Nevertheless, since people with a preoccupied/anxious attachment style make lower use of cognitive reevaluation than those with a secure attachment style, the former’s levels of anxiety and depression tend to rise. In the case of fearful-avoidant attachment, NSA is even lower and make a high use of emotional suppression, which impedes them from constructing secure emotional bonds. This suggests that NSA interacts with emotional regulation generating different results regarding mental health. Lastly, people with a dismissive-avoidant attachment style show the lowest scores for NSA and some of the highest on emotional suppression: it is possible that they tend to dissociate affectively, the reason why future researches need to explore if this factor actually explains these results.

This study had some limitations that require acknowledgement. One of these limitations regards the sample method: being and online study, and given that the participants were motivated to answer the questionnaire and thus obtain feedback on themselves, it cannot be ignored that there is a self-selection effect. It would also be desirable to conduct in-depth interviews in order to have a greater wealth of information, as well as more elements to understand weather the hypotheses raised are confirmed by participants’ narratives.

Despite the above, this study bases the notion of the role of NSA as a social adaptation strategy that is influenced on the attachment style and which interacts with emotional regulation to affect the mental health of a person. In doing so, it is relevant when interventions are conducted, to not look at NSA as an unfavorable element, despite the popular belief that encourages the opposite. Considering the obtained results of inferential test and the path analysis parallel mediator model, future research could be oriented towards analyzing the impact of interventions aimed at developing secure attachments, NSA and cognitive reevaluations. These variables are the ones most associated to the positive indicators of mental health, and, inversely with distress.