Compliance management in general and compliance officer in particular have the mission to prevent and manage the risk associated with eventual non-compliance with normative matters. During the last two decades, the importance of these figures has gained great importance for the management of organizations, and their implementation has spread around the world (e.g.; Open Compliance and Ethics Group, OCEG, founded in 2002). Its functions, among others, are to identify risks, analyze statutory and regulatory changes, determine preventive and corrective measures, perform surveillance and control tasks, implement the Compliance Management system, train managers and employees so that they know and apply all the rules and periodically review the updating of the procedures (Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission, COSO, 2017). Despite efforts to achieve higher levels of compliance, normative transgression continues to be a widespread problem in all types of organizations (e.g., Boda & Zsolnai, 2016; Detert et al., 2007; Greve et al., 2010; Healy & Iles, 2002). The prevalence, and even exclusiveness, of legal and economic perspectives when addressing the problems of compliance can partly explain this lack of success. Therefore, the addition of the theories of social psychology applied within the organizational sphere can enrich this perspective and increase its effectiveness. Indeed, Morris et al. (2015) recently proposed the development of Normology, which consists of the study of norms from different disciplines in order to obtain an integrated vision of their dynamics (i.e.; appearance, evolution and change) and its effects at the individual, group, and institutional level. In this sense, the authors point out four basic processes on normative compliance: internalization, social identity, rational choice, and the regulatory focus. In line with this theoretical thought and research action, we here propose the convenience of adding a new process, labelled as the normative appraisal, which refers to the perception of external normative appeals. External means that the message (appeal) comes from a source different from the individual (e.g., one relative, the Council, the organization). Normative means that the appeal indicates what one should (or should not) do in a given situation. In this work, we conducted three studies in order to test the validity of a normative diagnosis tool based on the premises of the evaluative model of normative appeals (from now on EMNA) regarding the normative appraisal and its influence on the compliance intention (Beramendi et al., 2022; Oceja et al., 2016, Oceja et al.,2021; Salgado et al., 2018).

Four (psychosocial) processes about normative (organizational) compliance

According to Morris et al. (2015), the influence of norms on behavior depends on the interrelation between objective and subjective elements. Regarding the former, they point out that the regularities derived from the beliefs and behaviors observed in a social group (e.g., driving and walking on your right), the sanction systems (i.e.; rewards and punishments applied to what is approved and censored), and institutions (i.e.; certain regularities crystallise in a formal structure that remembers and maintains them). As for the subjective elements, they first distinguish between descriptive and prescriptive (i.e.; injunctive) norms; that is, the perceptions and beliefs about what most people do in a given situation, and about what the reference group considers appropriate to perform, respectively (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004). Furthermore, they add personal norms, which are expectations about how one should behave in order to adjust oneself (Schwartz, 1977).

The interrelation between these elements refers to four basic processes on normative behavior. Different theoretical models have focused on proposing and verifying the importance of each of these processes. First, the process of internalization, which refers to the degree to which certain social patterns become personal principles that connect with our values and guide our behavior (Schwartz, 1977, Schwartz, 1994; Schwartz et al., 2012). Research has distinguished two types of internalization: introjection, when the personal norm is linked to an authority figure and to the feeling of guilt in case of transgression, and internalization, when the norm is linked to the values that define our self-concept (Thøgersen, 2006). The former would have more influence in public contexts and/or when the authority figure is visible, and the latter in more private and ethical decisions (Morris et al., 2015). Second, the social identity process influences general behavior and normative compliance in particular. People have the need to develop an identity, which is largely defined around the groups we belong to, and our behavior will depend on how we define ourselves (socially) at the very moment of realizing it (Tajfel, 1981; Turner et al., 1987). The Theory of Social Identity is one of the pillars of social psychology and its explanation exceeds the limits of this work. However, it is worth mentioning the importance that (Tyler & Blader, 2000) gave to establishing a link between the perception of the legitimacy of authority and the identification process to explain normative compliance within organizations (see Relational Model of Authority in Tyler & Blader, 2005; Tyler & Lind, 1992). Very succinctly, perceiving the authority (institution) as legitimate lead us to identify with it and, therefore, to be inclined to follow its guidelines. This perception of legitimacy depends on the degree to which we perceive that the authority allocates the available resources fairly regarding to both the outcome (distributive justice) and the procedures used to obtain it (procedural justice).

The third process refers to the rational calculation proposed by the Theory of Deterrence. It is assumed that people are rational, that their actions are under the power of the will, and that the decision-making process is based on the analysis of the costs and benefits associated with compliance or violation of norms (Andenaes, 1974; Beccaria, 1764; Becker, 2007; Cornish & Clarke, 2017). Consequently, normative management based on a rational deterrent approach emphasises the use of control and sanction to increase the level of adherence. Its utility has been analyzed both at the social level (Nagin & Paternoster, 1991; Paternoster & Bachman, 2012) and at the organizational level (Cheng et al., 2013, Cheng et al.,2014).

Finally, Morris et al. (2015) point out the attention process highlighted in the Focal Theory of Normative Behavior (Cialdini et al., 1990; Cialdini at al., 1991; Reno et al., 1993; Kallgren et al., 2000). This model raises two fundamental premises. First, the existence of two types of normative references that have already been discussed: descriptive and prescriptive norms. Second, these normative references will affect our behavior only if they are within our focus at the time; that is, they are salient. The empirical support received during the last three decades shows the usefulness of this model to explain a good part of the influence of social norms on behavior (Chung & Rimal, 2016). Morris et al. (2015) argue that, when salient, descriptive norms “automatically guide our immediate responses toward safe social direction” (p. 7), while prescriptive norms provide information that we deliberately process to contrast our action trend with that approved by the reference group. Using a nautical metaphor, they call these functions “autopilot” and “radar”.

Evaluative Model of Normative Appeals

Taken together, these four processes account for much of the explanations for why we meet with the norms. However, none of them deals directly with a recurring aspect in this field: on many occasions, the norms are presented as external and objective proposals; that is, as messages with particular characteristics perceived by those who encounter with them. Specifically, the situations we go through are full of notices, recommendations, guidelines that explicitly tell us what to do or not to do in a certain place (e.g.; not consume alcohol, use the bins, keep silent, complete a form, wash your hands, wear a mask, etc.). From the Evaluative Model of Normative Appeals (EMNA) (Beramendi et al., 2022; Oceja et al., 2016, 2021; Salgado et al., 2018) these messages are labelled as normative appeals, and it is proposed that, once they capture our attention, a perception process occurs (normative appraisal) that focuses on their content (recipient-place-action) and influences on our intention to comply with them. This normative appraisal is structured in two dimensions: formality and protection. Formality refers to the degree to which the proposal is perceived to come from an institution with the status and responsibility to ensure compliance. Protection refers to the degree to which the proposal is perceived to facilitate and allow the main action to be carried out (i.e., it provides freedom) and/or prevents physical or psychological harm from occurring (i.e., it provides security). In order to reduce the confusion caused by the polysemy of the terms of freedom and security, the authors of EMNA propose “caligae” and “scutum”, which in Latin refer to the sandal and the shield of the Roman legionaries (Oceja et al., 2021). According to the authors, both forms of protection (i.e., scutum and caligae) coexist and may influence on the intention to comply. Therefore, their separate measure and analysis allows clarifying its effect and, very importantly, to enhance the design of future interventions aimed at arising level of adherence to the proposal.

The authors of EMNA make two premises regarding the influence on the intention to comply with a normative appeal. First, the normative appraisal will produce a perception (cognitive representation) that can be characterised as one of the following four basic categories: legitimate norm (high protection and formality), prescription (high protection and low formality), coercive norm (low protection and high formality) and use (low protection and formality). It is important to note that the model does not propose that the individual consciously and explicitly classifies a normative appeal as belonging to each of these categories. Instead, it is proposed that the perception of the level of formality and protection of a specific normative appeal can be measured and subsequently classified in this way by the researchers. The results obtained in a study carried out on a sample that included four countries (i.e., Argentina, Spain, the United States and Venezuela (Oceja et al., 2016, Study 1) supported the possibility of carrying out the classification proposed by EMNA.

Regarding the second premise, it is proposed that each of the basic normative categories will provoke a level of willingness to compliance that follows a continuum that goes from the use and coercive norm categories, with a lower degree of willingness, to those of prescription and legitimate norm, with a higher degree of willingness. The results obtained in previous research supported this premise in studies carried out with the general sample (Oceja et al., 2016, Study 2), university sample (Oceja et al., 2016, Study 3; Salgado et al., 2018, Study 1), and employees of public companies (Salgado et al., 2018, Study 2).

In summary, as illustrated in Figure 1, EMNA proposes the need to add a fifth process (i.e.; normative appraisal) that, in conjunction with those already proposed and collected in Normology (Morris et al., 2015), allows explaining the intention to comply with a normative appeal.

Current Research

The main objective of this work is to test the usefulness of a normative diagnostic tool based on the EMNA premises, which have two characteristics. First, it analyzes the perception -in terms of formality and protection- elicited by each normative appeal, instead of focusing on evaluating the members (e.g.; personal characteristics, degree of identification, values, etc.), procedures (e.g.; sanction mechanisms) of the organization, or a general orientation towards compliance. Second, based on this perception, it aims at anticipating the intention to comply with each normative appeal assessed through the perceived agreement. We intentionally chose perceived agreement because is more anticipatory (proactive) of the future compliance; for example, a reported external compliance accompanied with disappointment can be misleading and not predicting the future actual compliance.

We therefore carried out three studies, the first in a general sample, and the following two in a multinational company in the Healthcare sector (“target” company) with a presence throughout the national territory. In the first two studies, we selected a set of 16 normative appeals actually applied in the target company, and developed a tool designed to measure the dimensions of the normative appraisal proposed by EMNA (i.e.; formality, and protection in its double meaning) within an organizational context. We did this adapting the instrument used by Oceja et al. (2016) and checking it first in a general sample of workers (Study 1) and later in the target company (Study 2). Two months later, in Study 3, we tested if the set of normative appeals showed a pattern of willingness to comply consistent with the previous diagnosis based on EMNA.

Study 1

We carried out Study 1 with a double objective. First, before applying the diagnostic tool in our target company, we first checked that it worked correctly in the general adult population. Second, Oceja et al. (2016, Study 1) obtained results that supported that the norms can be classified into the four categories proposed by EMNA. However, they did not contemplate the two forms of protection proposed in the more recent version of the model (Oceja et al., 2021; Salgado et al., 2018). Therefore, on this occasion we test the refined instrument, applied electronically, which includes measures of the two forms of protection: prevention of damage (i.e., scutum) and promotion of action (i.e., caligae).

We have three hypotheses. First, we expect that the diagnosis tool will allow classifying the set of normative appeals into the four basic normative categories proposed by EMNA (H1). Second, we expect that, along the set of the normative appeals, the measures of scutum and caligae will significantly correlate with each other, because both refer to the level of perceived protection (H2). Third, we also expect these measures will be significantly different from each other because they indicate two different aspects of the dimension of protection (H3).

Method

Participants

Three hundred and twenty-eight students from the Open University answered a questionnaire after reading and accepting the declaration of consent: 52% were men, their age range was between 18 and 65 years (M = 40.01; SD = 11.52), and 80% had at job at the time of answering the questionnaire.

Procedure

First, one of the researchers set three meetings with the head of the Human Resources Department of the target company in order to select a set of 16 normative appeals that are actually been applied in that company. As Table 1 shows, we selected appeals with different degree of formality and related to varied behaviors. Second, we developed the questionnaire adapted from Oceja et al. (2016) that measures the normative appraisal indicated by EMNA. This questionnaire was applied through an electronic platform (Qualtrics) to evaluate separately, sequentially and randomly each of the 16 proposals in two parts. Specifically, in the first part, each normative appeal was followed by two questions: To what extent does this proposal prevent you harm? And to what extent does it facilitate to carry out your action? The response scale was Likert type with 7 response options (1 = Nothing, 7 = Extremely). These two questions refer to the two forms of the protection dimension. In the second part, each normative appeal was presented again followed by the question Is it formal? (Yes / No), and those who answered affirmatively indicated to what extent through a Likert-type scale (1 = Nothing, 7 = Extremely). These questions refer to the formality dimension. The participants took around 7 minutes to complete the two parts of the questionnaire.

Results and Discussion

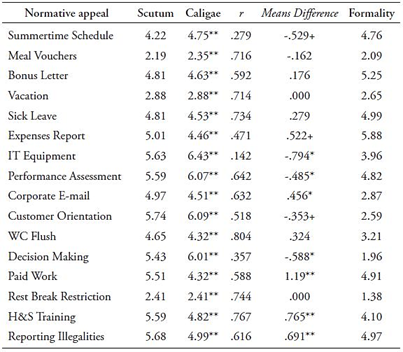

Appraisal of Protection

Regarding protection, we first obtained the correlation between the two forms of this dimension. As shown in Table 2, in line with our first hypothesis, the two forms significantly correlated with each other for all the normative appeals (.353 < rs < .609; ps < .001). In line with our second hypothesis, they showed significantly different values in 11 out of the 16 proposals (see positive and negative differences in 6 and 5 cases, respectively). In other words, the participants indicated that protection made special reference to the degree to which the proposal avoided harm (scutum) or allowed to perform the action (caligae).

Appraisal of Formality.

This dimension refers to the degree to which the proposal is perceived to come from an institution with the status and responsibility to ensure compliance. Table 2 presents the means of the formality index derived from combining the answer to the two questions about this dimension. Specifically, those participants who answered that they did not perceive it as formal were assigned the value of 1 (the lowest), and those who answered affirmatively were assigned the value of the following question about to what degree they perceived it as formal (7-point Likert scale).

Diagnosis through the analysis of the normative appraisal

In line with Oceja et al. (2016), we performed the cluster analysis technique to examine the perception of the 16 normative appeals in relation to the basic normative categories proposed by EMNA. This analysis allows obtaining the location of each proposal in the space formed by the dimensions of protection and formality. With respect to protection, we included the highest value of the corresponding form (i.e., scutum or caligae). Regarding formality, we included the value that indicated the level of perceived (1 = Nothing, 7 = Extremely). Next, we performed a K-means cluster analysis (4-cluster solution) with a maximum of 10 iterations.

Figure 2 represents the location of the 16 proposals in the space formed by protection (abscissas) and formality (ordinates). Therefore, the participants clearly perceived two proposals as uses (“restrict breaks” and “meal vouchers”), three proposals in the margins of the coercive norm (“informing regarding complementary paid work”, “deliver the bonus letter” and “enjoy the vacation throughout the year”), four as prescriptions (e.g., “customer orientation”), and seven as legitimate norms (e.g., “H&S training” and “proper report of the expenses”).

In summary, based on the EMNA premises, we combined the measure of the normative appraisal through the questionnaire with the cluster analysis to examine the final outcome. The results of Study 1 showed that this procedure allows classifying a set of actual normative appeals into the four basic normative categories proposed by the model. We propose to apply this classification as a diagnosis that may guide the decisions of those who have the responsibility to anticipate and manage the expected level of compliance. Next, we applied this diagnostic tool to the target company in the following two studies.

Study 2

The objective of Study 2 was to apply the EMNA-based diagnostic tool in a real company in order to test its practical utility.

The company is a multinational in the Healthcare sector with a presence in the country since the 70s. Its main business is the commercialization, distribution, installation and maintenance service of medical equipment for operating rooms, ICU and Emergency areas of both public and private hospitals; as well as the marketing and distribution of consumables. At the time of the development of this study, the company was made up of 150 workers (78% men) distributed in Front-Office (Sales, Marketing, Technical Service, Engineering) and Back-Office (Human Resources, Finance, Logistics, IT, Quality) departments.

Method

Following the procedure described in Study 1, we sent the link to the online questionnaire (Qualtrics) by email to 112 employees, a total of 82 answered it, with 68 valid responses (79%male) and 15 that were discarded because of the amount of missing values was superior of 10% (Bennett, 2001). The ages of the study participants ranged from 25 to 65 years. Before answering the questionnaire, all the participants read and accepted an informed consent.

Results and Discussion

Regarding protection, once again the assessment of the two forms were closely related to each other and, at the same time, reflected differentiated results. As shown in Table 3, all the correlations were significant, and 10 out of the 16 means showed significant or marginal differences. Next, we carried out the same analysis described in Study 1 by introducing the corresponding protection and formality values for each proposal and performed the K-means analysis (4-cluster solution) with a maximum of 10 iterations.

Table 3 Normative appeals, Scutum and Caligae means, Pearson’s correlation and means difference for these variables, and formality mean (Study 2)

+p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .001

Figure 3 presents the graphic solution of the cluster analysis. This diagnosis leads to two conclusions. First, most of the evaluated normative appeals (13 out of 16) were perceived with medium or high levels of protection, specifically four as prescriptions, and 8 as either clear legitimate norms (5) or in the margins of that quadrant (3). According to EMNA, these proposals will produce a high level of adherence in the organization. Second, there are three proposals that were evaluated as low in both protection and formality and, therefore, are expected to produce a low level of adherence.

In summary, the application of the EMNA-based diagnostic tool in a real company allows locating potentially problematic normative appeals, given that the expected willingness to comply with them is low. However, it remains to be tested whether the degree of the actual adherence associated with these normative appeals in the real context corresponds with the level anticipated from the diagnosis based on the premises of EMNA. That was the objective of Study 3.

Study 3

In Studies 1 and 2 we applied the diagnostic tool (questionnaire and cluster analysis procedure) based on EMNA in a general sample and in a specific business context, respectively. The objective of Study 3 was to verify if the diagnosis regarding the perception of the normative appeals corresponds to the levels of adherence hypothesized by the model.

Method

Participants

Three months after the Study 2, we e-mailed the same 112 employees who participated in Study 2 again asking them to complete a short online survey (Qualtrics). In this case, 80 employees (54 men, 25 women and 1 unidentified) with ages between 25 and 61 years participated. Before answering the questionnaire, all the participants read and accepted an informed consent.

Procedure

We again presented participants with each of the 16 proposals followed by the following question: To what extent do you agree with this proposal? They answered using a 7-point scale (1 = Not at all, 7 = Extremely). We decided to ask about the degree of agreement, because we considered that asking them directly about the level of compliance could evoke a greater demand in the answers. In this way, those who are very willing to comply with the normative appeal will have no difficulty in showing a high level of agreement, while those who are less willing to comply with it will feel more comfortable expressing that lower willingness through a lesser degree of agreement. Regarding the hypothesis, based on the diagnosis made in the Study 2, we expected employees to show a low level of adherence in the three proposals perceived as uses, and a high level in those perceived as prescriptions and legitimate norms.

Results and Discussion

To ascertain the differences in the degree of adherence caused by each normative appeal, we performed an intra-subject ANOVA and post-hoc comparisons according to the Bonferroni test. Table 4 presents the normative appeals ordered according to their degree of adherence and the significant differences between them. Therefore, thirteen proposals caused a high level of adherence, with mean values greater than 5 on a 7-point scale, and 3 proposals caused a low level of adherence, with values less than 4. This pattern was consistent with the diagnosis made in Study 2. Therefore, the diagnosis allowed us to anticipate which proposals were going to provoke this low level of adherence, and more specifically which two proposals may be problematic because they are mandatory norms not perceived as formal or protective (see Study 2): the distribution of holidays and the use of food tickets.

Table 4 Normative appeals, means and standard deviations in the degree of adherence, and normative diagnosis (Study 3)

Note: The means with different subscripts show significant differences, Bonferroni post-hoc test.

The diagnosis also allowed to anticipate an overall high degree of adherence, because most of the proposals are perceived as protective (legitimate norms or prescriptions). Regarding the comparison between the level of adherence provoked by legitimate norms and prescriptions, the higher level for the legitimate norms predicted by EMNA was not found. Specifically, for this set of normative appeals actually applied to the employees of a real company, the protection dimension was predominant over the formality dimension; that is, the proposals perceived as legitimate norms and prescriptions reflected high levels of adherence in an undifferentiated way.

In summary, employees showed a level of adherence, measured through the level of agreement with the corresponding normative appeal, which was consistent with the EMNA-based diagnosis. It is important to remember that the time distance between both studies was three months. This lag allows us to rule out a typical problem of using the self-report: the demand to show consistency between the responses related to the perception of the proposals (Study 2) and the level of adherence they cause (Study 3).

General Discussion

Theoretical Implications

The results of this work support that EMNA provides a theoretical framework to make hypotheses about how the normative appraisal may influence on the compliance of the employees of an organization. These hypotheses refer to the existence of (a) a two-dimensional evaluation process (normative appraisal) that results in a classification of four basic normative categories (legitimate norm, coercive norm, prescription and use) that (b) are associated with different levels of adherence to normative appeals and (c) allows guiding the most appropriate actions based on the resulting diagnosis.

The EMNA-based diagnostic tool allows addressing the problem of compliance from a different perspective, and complementary to other theoretical approaches highlighted by the Normology (Morris et al., 2015). For example, in this work we have not examined the degree of affinity or coherence that exists between the attitudes and values of the employees and the culture of the company. This information is relevant, because research suggests an intriguing and not yet elucidated relationship (Hofstede, 1998; Gregory et al., 2009; Killingsworth, 2012; Xanthopoulou & Bakker, 2012). However, the diagnosis here proposed provides information regarding perception and predictions regarding willingness to comply with specific norms. Indeed, without having to measure either the employees’ values and attitudes or the organizational culture, the diagnostic tool allowed to locate two normative appeals that might deserve attention. Nor did we have to measure employees’ opinion about the institution/agent responsible for both designing and enforcing those normative appeals. This kind of measurement is always relevant and potentially useful; however, it may occasionally be not pertinent, because it could arise unnoticed counterproductive attitudes. Finally, employees are likely to think that virtually nobody restricts the use of meals tickets and vacation times to one stipulated period, or even perceived that “free use” is generally regarded as the proper behavior. These (descriptive and prescriptive) normative references can explain why the transgression is maintained; however, they do not allow to understand why it occurs or to anticipate what it will occur. In summary, the normative appraisal proposed by EMNA is a process that can provide new keys to address aspects that are not fully covered by the processes proposed so far in relation to normative compliance.

Applied Implications

The application of a tool based on the EMNA model let the diagnosis of a set of normative appeals of real application in a company. This diagnosis may be useful to guide decisions that are especially relevant in the organizational environment. In this sense, when trying to manage normative compliance, the most common strategy has been to resort, often automatically and unilaterally, to direct control mechanisms such as surveillance, the application of sanctions, and the replacement of people. These strategies do not only imply great economic costs and potential damages for the organizational climate, but it has also been largely proved that by themselves they are not effective in achieving better levels of adherence (Martin & Harder, 1994 ; Killingsworth, 2012; Tyler, 2006).

The EMNA-based diagnosis, which focuses on the normative appraisal process, proposes a new alternative to the exclusive use of sermons and reprimands. First, we propose to measure the normative appraisal elicited by each normative appeal in a simple an unreactive fashion. That is, instead of directly asking employees if they intend to comply with what the normative appeal dictates, they are asked about the extent to which they perceive it as formal and, more importantly, as a means that prevents them from damage (scutum) and/or facilitates them to carry out their professional action (caligae). Second, we propose to analyze the data through an objective technique (i.e., cluster analysis) that locate the perception of each appeal in a space that theoretically represents the two-dimensional normative appraisal. This analysis can and should be complemented by others related to the contrast of means.

Finally, having three indices for each normative appeal (i.e., formality, scutum, and caligae) enable the design of future interventions aimed at increasing one, two or the three indices. In this vein, Thaler and Sunstein (2008) coined the term nudge (“encouragement”). This term refers to those interventions based on the knowledge provided by the social sciences-particularly Psychology, Sociology and Anthropology-that have low cost, are applied at a specific moment and situation, and are aimed at causing immediate changes in behavior (Guemes & Wences Simon, 2018). In their work, these authors describe and analyze different types of actions such as asking unemployed people to write an action plan, placing the healthiest foods at eye level in the school canteen, drawing a series of lines on a dangerous section that increases the feeling of speed, place a financial decision as the “default option”, and so on. Following this perspective, we are currently working on developing and contrasting interventions that “nudge” the employees of an organization to perceive as legitimate norm, or at least as prescriptions, those normative appeals that are perceived as coercive norms or uses (Úbeda, 2020).

Implications in the Organizational Context

As mentioned at the beginning of this work, a considerable number of companies have self-imposed codes of good practice with the aim of promoting both compliance and corporate social responsibility. Tziner et al. (2011) suggest that both aspects are closely related to organizational justice and job satisfaction. In this work, we add that these codes of good practice will be useful as long as they are translated into normative appeals that are perceived as legitimate norms or prescriptions. On the contrary, if they were perceived as coercive norms or uses, they would not only involve the risk of greater non-compliance, but they could also cause a series of perverse effects (Fernández-Dols, 1992; Oceja & Fernández-Dols, 2006). The EMNA-based diagnosis permits the prognosis of this type of problem and provides clues on how to design and plan an intervention (nudge) that affects the normative appraisal elicited by these appeals.

Besides, the research on Authentic Leadership (Avolio et al., 2004; Azanza, Moriano & Molero, 2013) proposes that the promotion of an organizational culture oriented to flexibility, with corporate pillars such as collaboration and innovation, can be especially valuable in contexts of high business competitiveness. In this sense, having a diagnostic and normative management tool can assess the possible effects of the generational contrast and provide greater flexibility to the organization.

Future investigation lines

The results of the present work claim for three lines of investigation to be addressed in future research. First, the results suggest that both prescriptions and legitimate norms were associated with high adherence, without clearly differentiating between them. Likewise, on this occasion, no proposal was clearly perceived as a coercive norm, which did not allow comparing the degree of adherence with respect to the other representations. The evidence obtained so far is not conclusive, with two studies showing significant differences (Oceja et al., 2016; Study 2; Salgado et al., 2018, Study 2) and one without showing them (Salgado et al., 2018, Study 1), so more research is required. It will be necessary to carry out new diagnoses on a more extensive and diverse set of normative appeals, in larger and more heterogeneous samples, applied in different real contexts.

Secondly, this is the first work in which the double form of protection is used to diagnose a set of concrete normative appeals, and the results suggest that the forms of caligae and scutum are closely related to each other, although they are not equivalent. Indeed, obtaining information concerning both forms prevent from making the mistake of evaluating one specific proposal as not protective, because the form that is actually covering was not contemplated in the measurement. The results of this work suggest that the chance of this kind of error is low, but it should be borne in mind that the participants answered the questions on each of the two forms consecutively, so that conducting research to evaluate each form separately is pending.

Finally, our main aim when developing this diagnostic tool based on EMNA is to anticipate the willingness to comply with specific normative appeals in order to proactively design and apply interventions (nudges). We are not trying to predict the actual compliance. Theoretically, the greater the willingness to comply the higher the level of actual compliance; however, as shown in Figure 1, these two variables are not equivalent. The cost-benefit analysis, the strength of the decision and the opportunities given by the specific situation affect this relationship. Indeed, regarding the operationalization of the normative compliance, it is always a challenge to select and obtain proper measures. These measures should refer to behavior as directly as possible while their selection should avoid three potential costs. First, psychological, because participants may try to offer a socially desirable image when directly report their compliance; second, economical, because it not easy to unobtrusively observe their actual compliance in a regular basis; and third, ethical, because this kind of surveillance may be in conflict with the privacy of the observed participants. Nevertheless, and fortunately, the study of the willingness to comply allows getting closer to the intricate issue of the normative compliance.

In summary, the theoretical premises of EMNA have stimulated the development of a tool useful for conducting a normative assessment that may, in turn, promote more efficient management (Brunet et al., 2020). This type of tool may reduce the probability of making wrong decisions by choosing the necessary strategies to achieve better levels of compliance. In other words, a theoretically-driven instrument aimed at avoiding the bad practice of investing significant amounts of human and financial resources in measures that do not contribute to truly improving the functioning of the organization.

Data availability

The data corresponding to these studies are available on Open Science Framework (OSF) website (https://osf.io/95ndp/) (Blinded, 2020).

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in the studies were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (CEI 64-1140, UAM) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Statement

Dear Participant, this research aims to understand and analyze beliefs and attitudes towards both abstract and specific concepts. The participation is completely anonymous and the information obtained will be confidential, so the anonymity of the responses will be protected to the full extent of the law. Participation in this study requires that you are 18 years of age or older. If you agree to participate, you will be asked to answer a set of questionnaires that will take between 15 and 30 min in total. Your participation is voluntary, and you can stop participating in the study at any time, without giving any reason, and without any penalty or consequences. The results will be used only for academic/scientific purposes. Any questions you might have during the research process can be directed to (name and email address of the first author).