In this article, we first present an overview of studies on collective memory and social representations of history. Collective memories are widely shared knowledge of past social events deemed relevant for the collective identity, which may not have been personally experienced, but are collectively constructed through communicative social functions (see Maswood et al. 2019; Wang, 2021). Finally, we exemplify the life course approach on collective memory with empirical studies from the CEVI project, and describe part of the results of the study conducted in Gaza, Palestine.

Autobiographical and collective memory

Autobiographical memory (e.g., Conway, 2005; Nelson & Fivush, 2020) is the system responsible for storing episodic memories related to the self; it is constructed throughout a person’s life and forms part of his or her biography and identity (e.g., Fabry, 2023; Sutton, 2022). In autobiographical memory, effects such as the critical period of recall (also called critical age or reminiscence bump) or positivity bias have been found (Hitchcock et al., 2019; see also Salgado & Kingo, 2019). The first refers to the tendency to over-remembering those personal events lived in a specific span (i.e., critical age effect, approx. 10-30 years), which is considered the formative period of social identity in which individuals are more open to live new life experiences and, therefore, remember them as the most meaningful (Koppel & Rubin, 2016; see also Munawar, Kuhn, & Haque, 2018). On the other hand, the positivity bias of memory refers to the tendency to remember more positive than negative personal life experiences (Walker et al., 2003), which highlights the importance of the type of emotions experienced during the event. This is an essential attribute, since what is remembered is not the objective fact, but also the subjective experience derived from it (Ruíz-Vargas, 2010). At an individual level, collective memories are a semantic memory of historical events (Malle et al., 2018), including memory of the event (e.g., my knowledge on WWII). However, they can also be autobiographical memories related to personal experience linked to these historical events (e.g., my direct experiences related to WWII, such us personal feelings or interpersonal and mass media information that I experience regarding WWII).

Collective memory of the 20th Century

Social memory as a field of study was originally called collective memory, and Maurice Halbwachs is often pointed out as its pioneer (Hirst, Yamashiro, & Coman, 2018). Based on people’s interests and prevailing social frameworks (i.e., schemas), he defined collective memory as the reconstruction of the past by members of a group (Halbwachs, 1950), an instance that helps the maintenance of a groups’ identity, as well as its core values (see Rottenbacher & Espinosa, 2010). In fact, he proposed that group memories are the elements that hold the collective memory1 together. Schuman and colleagues conducted a series of studies (Schuman & Scott, 1989; Schuman, Vinitzky-Seroussi, & Vinokur, 2003) which focused on investigating people’s beliefs about the recent past (last 50 or 70 years), as well as their relation to their age at the moment of the event. In the first half of the 20th century, Karl Mannheim introduced the idea of “generation consciousness”, which refers to the social facts and changes to which each generation is exposed especially during youth (Mannheim, 1952). The critical age hypothesis (also known as reminiscence bump in the autobiographical memory studies previously described), states that sociopolitical and collective events that occurred when people are between 12 and 30 years old are remembered more (Holmes & Conway, 1999; Janssen et al., 2008; Schuman & Corning, 2012). Studies generally showed a generational or critical age effect for the recall of historical events (e.g., Ester et al., 2002; Schuman et al., 1998; Schuman & Scott, 1989; Schuman et al., 2003; Scott & Zac, 1993). For instance, in 1985 older Americans mentioned the Great Depression and WWII more frequently as important historical events, whereas younger participants more frequently mentioned the assassination of JFK and the Vietnam War - events that had occurred during participants’ early adulthood (Schuman & Rodgers, 2004). However, political events seem to be remembered more by those in their late twenties, in the end of the critical age (Schuman & Corning, 2000), and some events like great wars or dictatorships are important or shocking enough to be recalled throughout generations (Páez et al., 2018; Vinogradnaitė, 2018), which is referred to as the period effect.

Politics and warfare feature prominently in collective memory studies, with World War II being the most frequently mentioned event (see Liu, 2022). Moreover, different events that occurred in Europe and North America are more salient than those that occurred elsewhere. Nevertheless, socio-centrism can also be observed (Ellermann et al., 2008; Schuman et al., 2003; Scott & Zac, 1993), and local events may be remembered more frequently than events occurring elsewhere (Griffin, 2004; Cavalli, 2016). Studies with this approach also found a positive bias toward events in the long past- i.e., evaluated more positively than recent events (Ester et al., 2002; Schuman et al., 1998).

Social representations of world and national history

Collective memory and similar concepts can be interpreted through the theory of social representations. Like collective memory, social representation is a concept that has its origins linked to Durkheim’s (1912/2012) ideas on collective representations. However, it was Serge Moscovici who argued that collective representation was not an adequate concept to analyze modern societies because, unlike the traditional ones, are fluid and continuously changeable (Moscovici, 1998a). Consequently, while collective representations symbolize the static elements which maintain traditional societies cohesive, the objective of the theory of social representations is to analyze the points of tension in representational systems that generate changes in social organization (Moscovici, 1998b). These points of tension are characterized by the appearance of something unfamiliar, unknown or meaningless, and due to the fact that something meaningless is highly difficult to grasp, representational work is produced to make the unfamiliar meaningful, while allowing the appearance of new representations (Liu & Khan, 2021). Collective memories are not only shared individual memories, but also social representations maintained by informal communication, commemorations, memorials, textbooks and others, as cultural tools that exist to preserve the past. These social representations or shared knowledge about the past are elaborated, transmitted and preserved in a society through both interpersonal and institutional communications and are related to social or collective identities (Bobowik et al., 2010; Liu & Páez, 2019).

A method of research in this line of social representations of history has been aimed at verifying the most recalled events in world-history. This tradition is characterized by the conduction of cross-cultural studies, and they also provide evidence supporting the mixture of Western-centrism and socio-centrism in the content of collective memory (Cabecinhas & Évora, 2007; Liu et al., 2005; Madoglou et al.2010; Pennebaker et al., 2006). Socio-centrism or “collective narcissism” regarding the national role of in-groups in-world history was largely dominant, particularly in collectivist and high-power distance cultures (Zaromb et al., 2018). However, in some countries such as African nations and Turkey, socio-centrism clearly surpasses the West-centrism (Cabecinhas et al., 2011; Özer & Ergün, 2012). The positive bias for events in the distant past was also observed in studies of social representations of world history (e.g., Cabecinhas & Brasil, 2019; Cabecinhas et al., 2011; Cabecinhas & Évora, 2007; Liu et al., 2005; Madoglou et al., 2010; Pennebaker et al., 2006). From a complementary SR’s approach, a cross-cultural study using a closed-list confirmed the Western-centrism and positive representation bias of events in the distant past (Zaromb et al., 2018). However, wars were not as salient as in the free recall studies. When asked to evaluate a closed list of events, the industrial revolution is evaluated as more important than many wars (Techio et al., 2010). Social identity seems to influence social representations of national history in different ways (Huang, Liu, & Chang, 2004). For instance, WWII is more recalled in the victorious countries and those with a higher proportion of casualties (Abel et al., 2019; Bobowik et al., 2014; Páez et al., 2008).

The objective of this article is to examine the content and regularities of collective memory as described above. In particular, the predominance of collective violence and political-military contents of the events mentioned as memorable. Although some studies have found this bias towards violence and negativity, other studies suggest that collective memory does not necessarily have a negative valence. As well as the bias, to mention of events linked to the nation to which one belongs. In addition, we examine whether there is a cohort or critical period effect or greater mention of historical events experienced in the formative years of identity. Finally, we will examine whether the content of collective memory is associated with individual and social well-being.

In this way, we want to provide an evidence-based view on the content, regularities and consequences of collective memory. Retrospective survey data from 9 countries in the Americas and Europe that have already been published, but never analyzed together, was reanalyzed, as well it is exposed a study carried out in Palestine, a society in a stable political-military conflict. The aims are twofold. On the one hand, to learn about the content of socio-historical memories recalled by participants from nine nations from the Americas, European and Palestine. On the other hand, to examine the prevalence of negative collective memories, socio-centrism (or nation-related event memories), a cohort or critical age effect in the recalled events, as well as the association between the valence (or positive vs negative content) of recalled historical events and wellbeing. Based on a previous review, it is expected a prevalence of political-military events, and a prevalence of locally (vs international) recalled events. Further, it is also expected a critical age (or cohort effect) and period effect among local events.

Study 1: A life course approach on collective memory, The CEVI studies

As a way of approaching social representations of history, different studies have used a free-remembering approach (e.g., Broomé et al., 2011). The CEVI (Changements et événements au cours de la vie / Changes and events across the life course) was designed and developed at the University of Geneva (2003). To date, CEVI is taking place in 15 countries. These studies aimed to investigate the socio-historical events that had most affected participants’ lives and, therefore, their social representations. A series of studies grouped in the international CEVI research program (see Cavalli et al., 2006; Lalive d’Epinay et al., 2008) seek to explore what people remember and how they do it; they analyze cohort effects by selecting convenience samples of differentiated age groups. In this article, we will present a synthesis of nine studies carried out with the CEVI methodology, examining the content of collective memories and contrasting the generation effect by means of a meta-analysis of the generational or critical age effects found in them.

The specific objectives are to learn about the content of socio-historical memories recalled by participants from nine American and European nations. Hypotheses based on previous revision are the following:

Method

Participants

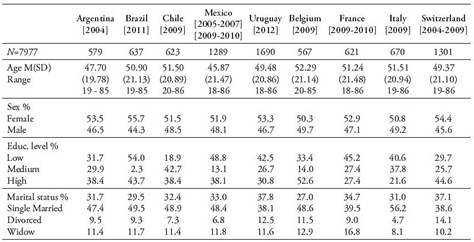

Data from surveys conducted in nine countries and previously published as articles were reanalyzed. In a cross-sectional and retrospective design, an open-ended and free-recall questionnaire was applied to adults’ sample. Large convenience samples from 18 to 85 years old, spanning the life course from youth to old age (socio-demographics in Table 1). Data collection was carried out between 2004 and 2012. After sign an informational consent, self-report questionnaire lasting approximately 30-45 minutes was administered, where the responses were coded using the CEVI coding grid. An Ethics Committee did not evaluate the CEVI studies presented in this work because it was not required in the settings in which they were carried out. However, the procedure used in the CEVI protocol has the approval of the Ethics Committee of the University of the Basque Country (Ref: M10_2018_224) linked to a doctoral thesis [http://hdl.handle.net/10810/56364].

Measures

Remembering of historical events. The CEVI questionnaire consists of three main fundamental blocks of open-ended questions on the perception of changes, socio-demographic characteristics (age, sex, marital status, educational level, etc.). The first two sections focus on the individual sphere and the third on the collective sphere -which is the part reported in this article. After two questions about the most significant changes in their lives (during the last year, respectively in the whole life), participants in CEVI were asked the following question: “Consider the main changes and events which occurred in your country and in the world during your life. What are the ones which most struck you?” (Please, mention up to four events). For each change (up to a maximum of four) participants were asked to describe them, justify the choice, indicate the time and place of occurrence and, finally, evaluate event valence. The instructions and response options were: “Now, indicate from the following options how you value this change or event”: Gain; Loss; Both; Neither; I would not know. The last two questions were not considered because they constituted a residual minority of less than 1%. A gain and a loss indicator of 0 to 1 was created for each participant, taking into account only positive and negative ratings-leaving out the ambivalent ones of calculation, neither and I wouldn’t know according to the total number of memories mentioned. For example, a person who answered four socio-historical events and evaluated 2 as gain, 1 as loss and 1 as ambivalent, would have a score of 0.5 on the gain indicator and 0.25 on the loss indicator.

Positive events are those evaluated by the majority as gains and negative events are those evaluated by a majority as losses. Two blind judges classified the events into categories or types of events. The valence rating of the events was based on how the participants had rated them. Events rated by more than 60% as losses or gains were rated as negative or positive.

The type of events mostly evaluated as losses or negatives were as follows: collective violence (such as the Gulf War and operation, Desert Storm, or 9/11 attacks), collective catastrophes (tsunami or earthquakes), natural death of leaders, political crisis, and assassinations or attempted assassinations of leaders (JFK assassination, death of the Pope), social and economic crises or events (e.g., the serial killer Doutroux, fear of crime or citizen insecurity, the 2008 Crisis, inflation). The types of events that were mostly evaluated as gains or positive were the following: social mobilizations (e.g., May ‘68, Zapatista mobilization in Mexico), creation of institutions (e.g., monarchy, introduction of the Euro currency), technological advances (Internet, man on the moon) positive sporting events (world or continental football cups). Agreement among judges was over 90% and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The valence rating of the events was based on how participants had rated them. Events rated by more than 60% as losses or gains were rated as negative or positive.

Meta-analytical procedure

To analyze the generation effect, the association of certain events to specific age groups, a meta-analytic synthesis of CEVI studies was carried out. That is, a systematic literature search with search criteria as could be PRISMA (Moher et al., 2016) or APA Meta-Analysis Reporting Standards (MARS) was not perfor3med. The difference between both procedures lies in the fact that, our intention is not to collect all available information on a specific topic, but, rather, a more in-depth or comprehensive analysis on the so-called generation effect. All the studies included were conducted under the same procedure and instruments: the CEVI protocol. The objective was to integrate all results where there was a difference between cohorts in all studies performed with the CEVI protocol. Other articles have performed meta-analytic syntheses of homogeneous studies, for example on collective effervescence (see Páez et al., 2015). If the result followed a profile similar to the generation effect, that is, if it showed an over-mention of historical events that occurred during the critical age or the formative period of identity (12-30 years), it was integrated. For instance, in Chile a 54.8% of people having 12-40 years during September 11 Twin Towers mention this event, compared to 17,6% of other cohorts, Chi = 53.3, p = .0001 and Phi = .35. Comparing the mention of historical events among cohorts located in the identity formative period versus other cohorts, a meta-analytic synthesis of such associations was performed, using the Chi-square statistic as contrast and the dichotomous Phi correlation as effect size. The Chi-square value was transformed into r following the formula of Rosental & Rosnow (2008). The CMA program and the random model were used for the meta-analytical synthesis.

Results

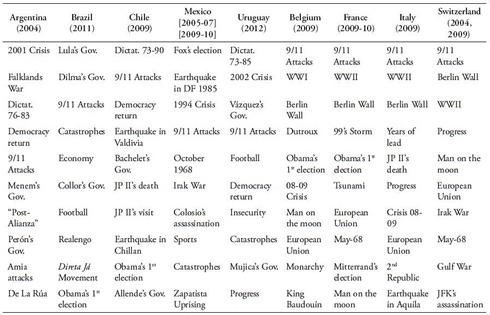

Table 2 shows a summary of the 10 most recalled socio-historical events from the CEVI studies between 2004 and 2012 in nine countries (Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, Chile, France, Italy, Mexico, Switzerland and Uruguay). In general, collective memory is mostly linked to historical periods related to collective violence. In Latin American countries such as Argentina, Chile and Uruguay, dictatorships have a prominent place, while in Western European countries, wars (specifically, WWII) are the most salient events. Nevertheless, and in contrast with the Latin American countries, there is a greater recall of socioeconomic events linked to discoveries and the creation of institutions, which shows a social representation of world history linked to openness and progress (for example, European Union and Man on the moon). In the Latin American region, the historical events remembered are more focused on internal elements such as, for example, governments in power or democracy returns, reflecting more political-centered social representation of history.

Table 2 Ten Most Mentioned Socio-Historical Events During Participants’ Life (source: CEVI Studies).

Note: Each column shows the most remembered events in a descending order. Dictat. represents dictatorship (Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay); Gov., government (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Uruguay), JP II, Pope John Paul II (Chile, Italy).

We conducted a meta-analytical synthesis based on CEVI studies, including the most mentioned events lived by a particular age group whose members had lived the event during their critical period (i.e., between 10 to 30 years). In this way, we were able to compare the probability of having mentioned the event (i.e., PHI coefficient, a dichotomous equivalent of correlation, which is then reported in Pearson’s r as effect-size) by this particular group versus others who were not in the critical period when the event occurred (Figure 1).

Note. Forrest plot of the random effects model that meta-analyzes the probability of mentioning an event by a specific age cohort (i.e., those who lived the event in the critic-age period). The criteria for selecting the events were based on the highest probability of mentioning (a), and the possibility of several age groups having lived it (b).

Figure 1

Results of the random effects meta-analysis show that the correlation of mentioning the event ranks from r = 0.030, (95% CI [-0.048, 0.107]), in the case of Brazil for the event Collor’s impeachment, to r = 0.360 (95% CI [0.292, 0.424]), in the case of Italy, for the event 9/11 Attacks. We can see that there are additional sources of differences that could explain these effects (Q (21) = 226.339, p < .001), and that the pooled effect is positive and significant (pooled r = 0.199, [0.153, 0.245]; τ 2 = 0.012, SE = 0.004; I 2 = 90.72). Because of the limited number of studies, no moderator analyses were performed to account for this large variability.

Discussion

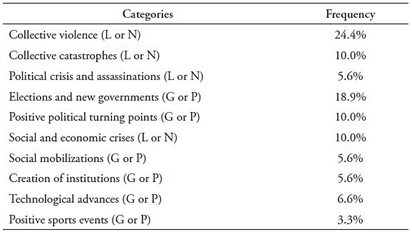

Based on these nations and the ten most mentioned events, similarities with other studies on collective memory and social representations of history are evident and supports H1: the most mentioned or recalled events are wars, political and collective violence-related events, as well as catastrophes. The content of studies on collective memory (see Páez et al., 2018) indicates that episodes of collective violence such as the Gulf War and operation Desert Storm, or the 9/11 attacks, ranked first in frequency, and the 9/11 attacks is the only event that appears among the most cited in all countries. As for collective violence, mentions of recent wars (e.g., Gulf War or Falklands War) are also relevant. Collective catastrophes ranked third with studies dealing with episodes such as the earthquake in Mexico DF (in 1985). A smaller number of events concerned death of famous people, focused on the natural deaths of important political figures and political crises, or episodes of political violence, such as the assassination of political leaders (e.g., Colosio in Mexico, JFK in the US), or assassination attempts (categories frequency in Table 3). The content of previous studies on social representations of history (e.g., Liu et al., 2005) is also similar to our results. In addition to the above, in the case of the European countries analyzed in our study, once again can be observed a social representation with a Eurocentric bias, centered on the socio-historical events of greatest significance for the European region and its sociocultural values. The salience of events related to the construction of the European Union project, shows an important shared element among Europeans (see Moscovici, 1988). In the case of Latin America, the representation is more ethnocentric.

Table 3 Event Categorization

Note: Gains or Positive events (G or P) 50% and Loss or Negative events (L or N) 50%.

Wars and political and military events are considered as historically important, which supports the first part of H1. However, it does not support the second statement of H1, the remembered historical events are not evaluated mainly as losses or negatively: regarding their valence, half of them have a negative evaluation, suggesting a significant proportion of positive evaluations. Among the socio-political ones, around a half have a clear positive valence (i.e., they are considered as positive political turning points, such as the creation of institutions, the return of democracy) or are related to partially positive social changes (e.g., governments changes, social mobilizations). Elections and new governments rank second among the most cited events in CEVI. Specifically, the first election of US president Barack Obama is internationally mentioned, but also events related to governments associated with important changes, like the first government of Perón in Argentina, Fox’s election in Mexico or the governments of Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff in Brazil. Positive political turning points have an important presence and rank fourth (e.g., the return to democracy in different Latin American countries, and the fall of the Berlin Wall in Western Europe), along with economic crises (e.g., the 2008 Crisis, inflation). Next, social mobilizations (e.g., May ‘68, the Zapatista mobilization in Mexico, the movements in favor of free elections in Brazil) followed by the creation of institutions (e.g., the creation of the European Union, the introduction of the Euro currency), technological advances, and the exploration of the moon, are events that are positively valued and largely mentioned. Following this, there are positive sporting events, such as world or continental football cups and the organization of the Olympic Games. In this sense, in these nations, despite the important conflicts and social problems of the past, there is a positive bias or a tendency to record both positive and negative collective experiences, although not with the positivity bias or majority recall of positive events found in autobiographical memory (Schlagman et al., 2006; Walker et al., 2003).

Research has also revealed a tendency toward socio-centrism, which we see in the fact that most nations consider their national historical events to be more important than events unrelated to their own history. Our results support H2. Still, even if people globally exhibit some ethnocentrism in their view of universal history, the socio-centric bias does not hold for all nations. In Western Europe there appears to be a common memory space with few national events mentioned, there are almost none in the study from Switzerland, a country that seems to be “without history” (Cavalli, 2016; Lalive d’Epinay et al., 2008; Martenot & Cavalli, 2014). Further, Latin American “new nations” exhibit stronger socio-centrism than European countries (Oddone & Lynch, 2008; Paredes & Oberti, 2015; Concha & Henriquez, 2011; Guichard & Henriquez, 2011). Participants from non-Western countries exhibit ethnocentrism by mentioning - and giving them world-historical relevance - those related to the creation of their own state (e.g., decolonization), while devaluing events linked to the history of neighboring countries that did not affect their own historical trajectory (Páez et al., 2018).

Finally, the meta-analysis results confirm H3 or that there is a general tendency of finding a positive and significant relationship of the age group that lived the event and the probability of mentioning in through free recall (see Páez et al., 2018 for a fixed model meta-analysis of others studies including those of Schuman and colleagues). However, this significant effect of the critical period was found to be only one quarter of the most mentioned events in the CEVI studies presented here. Conversely, this revision also shows that an important part of the ten most mentioned events have been mentioned by different generations that were alive during the event. These events share common features, such as the social importance for the ingroup and the high-intensity of emotional burden. These results suggest that a period effect exist for people living important events (Vinogradnaitė, 2018).

Study 2: CEVI Palestine

In the following study, we report recent data from the Palestinian CEVI study. Regarding socio-historical events, a tradition of studies has shown a relationship between exposure to collective violence and mental health at the individual level (e.g., Pedersen et al., 2008; Tol et al., 2010; Ventevogel, 2016) and at the collective level (Pedersen, 2002) in different countries. A study conducted with a large sample of adolescents in Palestine (Giacaman et al., 2007), showed that exposure to acts of collective violence has a strong relationship between the exposure to traumatic and/or violent events and adolescents’ mental health. In this study, we will examine the relationship between the content of collective memory and wellbeing, as has been done in the Basque Country (Méndez et al., 2022).

The objectives of this study are twofold: first, it aims to find out the content of the socio-historical memories recalled by Palestinians living in the Gaza Strip, as well as any differences they had based on a comparison among age groups (i.e., cohort versus period effects). Second, we explore the impact that these events have in the self-reported measures of well-being.

We have the following hypotheses:

A prevalence of political-military and negative memories is expected.

Most of the events belong to the local (vs. international) sphere.

Cohort effects are expected to be found in the recalled events.

Finally, negative versus positive appraisal of remembered socio-historical events is expected to be associated with low versus high well-being.

Method

Participants

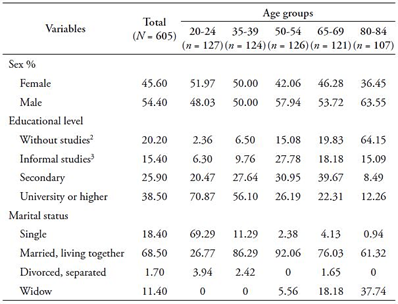

A cross sectional and retrospective survey was carried out with a large convenience adult sample in Palestine. This section shows the socio-historical part of the CEVI study carried out in the Gaza Strip, Palestine, during 2016-2017. There are reported data from 605 participants (54.4% women), with ages between 19 and 86 years (M = 51.24; SD = 20.42), and all residents of Gaza. This convenient sample was selected under the criteria of belonging to one of the five age groups given in the CEVI methodology. Therefore, the groups consisted of those between 20-24 years (M = 22.95, SD = 1.81), 35-39 years (M = 37.81, SD = 2.13), 50-54 years (M = 52.45, SD = 2.24), 65-69 years (M = 67.22, SD = 2.22), and 80-84 years (M = 80.9, SD = 1.91) (see Table 4). 99.8% indicate they were Muslims and 74.5% indicated neither a political identification with the left, nor the right (which was 8.9 and 16.5%, respectively).

Measures

Remembering of historical events. The CEVI questionnaire previously described was used. Participants were asked the following question: “Consider the main changes and events which occurred in your country and in the world during your life. What are the ones which most struck you?”. After the memory-description section, a measure of well-being was included.

Wellbeing. To measure wellbeing Pemberton Happinness Index or PHI scale was used (Hervás & Vázquez, 2013). PHI is composed of 11 items measured with a Likert scale from 0 = Strongly Disagree to 10 = Strongly Agree. Items evaluate: Subjective Cognitive Wellbeing (item 1, “I feel very satisfied with my life”); Vitality (item 2) “I feel energetic enough to accomplish my daily tasks well”; Eudaimonic Wellbeing (items 3-8), “I feel that my life is useful and valuable”; Subjective affective Wellbeing (items 9 and 10), “I enjoy every day many little things”; Social Wellbeing (item 11), “I feel that I live in a society that allows me to develop fully”. Total and facet scores were calculated.

Results

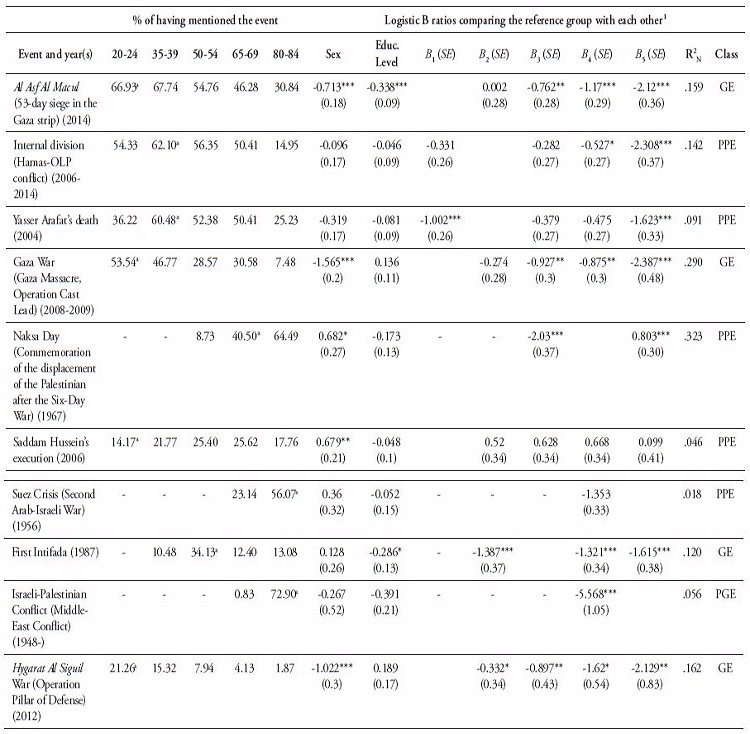

Most mentioned historical events in Palestine. First, from 2149 socio-historical events recalled, we selected the 10 most mentioned, which are presented in Table 5. The individual experiences range from having been mentioned by more than a half of the participants (54.05%), to only a dozen (2.31%). Among them, it is observed a 60% of war and conflict-related events (e.g., the 53-day siege to Gaza in 2014), deaths and assassinations of emblematic figures 20% (e.g., Yasser Arafat, Sheik Ahmed Yassin) and political crisis 20% (internal Palestinian division and first intifada). As can be seen, the collective memory of Palestine is mostly composed of socio-historical events linked to collective violence. It can be observed an in-group and its suffering focused representation of national history, which in turn contains a social representation of a nation historically in struggle.

Table 5 The 10 Most Mentioned Socio-historical Events

Note: ƒ, frequency, it indicates the mentioning percentage on the total sample (605). 2 it indicates the mentioning percentage on the total of events recalled (2149). The type of event represents whether the event occurred within Palestine and/or in Israel (local), versus those that occurred in a different country.

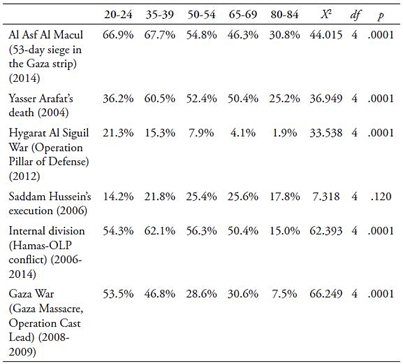

Age-related effects. In further analyses, we tested whether these events produced generational or critical age effect. In doing it so, we conducted logistic regressions (data shown in Table 8 as supplemental material). The analyses were performed with the aim of predicting the mentioning of each event (i.e., mention vs no mention) by the age groups, while controlling by sex and educational level. The age groups were treated as indicators in the analyses - they were introduced as dummy-coded variables - and thus, we were able to compare one group of reference to the rest in a separate way. The reference group for each analysis was selected considering the age they were when the event happened. Specifically, we took as a reference group the one whose members were closest to the critical age when during the event (i.e., between 10 and 30 years).

The analyses show that, among the 10 most mentioned events, there are four that produce generation effects (i.e., an increase in the likelihood of mentioning due to having lived the event in the critical age of development). These events rank from those clearly more mentioned by those in the critical age (e.g., the Gaza War, 2008-2009), to those with a less clear pattern (the Israeli-Palestinian conflict). Further, the rest of the events are classified as possible period effects, due to fewer differences in the percentage of mentioning among the age groups, and we consider them shocking enough to transcend different generations (e.g., Internal division, 2006-2014; Saddam Hussein’s execution, 2006).

To examine the differences in recall among the five age groups, six of the ten most recalled socio-historical events were analyzed, those that took place on dates after the year 2000, here, the youngest age group (20-24) had already been born. Three of six events, like Al Asf Al Macul (53 days of siege in the Gaza strip) (2014), Hygarat Al Siguil War (Operation Pillar of Defense) (2012), Gaza War (Gaza Massacre, Operation Cast Lead) (2008-2009), were mentioned with high frequency by the youngest age group, suggesting a temporal proximity effect to the event - the 20-24 and 35-39 age groups mentioned more frequently these more recent events for them. Two of the events, Saddam Hussein’s execution and OLP-Hamas conflict or internal division, show a period effect; the frequency of recall was similar across age groups, although the older ones recalled the latter significantly less (see Table 6). A similar profile was found for Arafat’s death, which was less mentioned by the older cohort. Overall, the results show a lower generation of memories by the older generation in relation to the six events examined - probably due to both temporal distance of the events and lower cognitive ability, although these are only speculative explanations.

On the other hand, the variables sex and educational levels were mainly introduced as control variables (see Schuman & Scott, 1989), but remarkably, we can see that the sex significantly explains the mentioning of several events. For instance, when significant, women show a greater possibility of mentioning most of the collective armed conflicts (e.g., Al Asf Al Macul, Gaza War, Hygarat Al Siguil War).

Table 6 Frequency and Comparison of Recalling among Age Groups

Note: X2, represents the Chi-square test of comparison of recalling and event (versus not) among the groups. df, represents degrees of freedom. The six events presented here correspond to the selection of events that could have been mentioned by all participants because of their age.

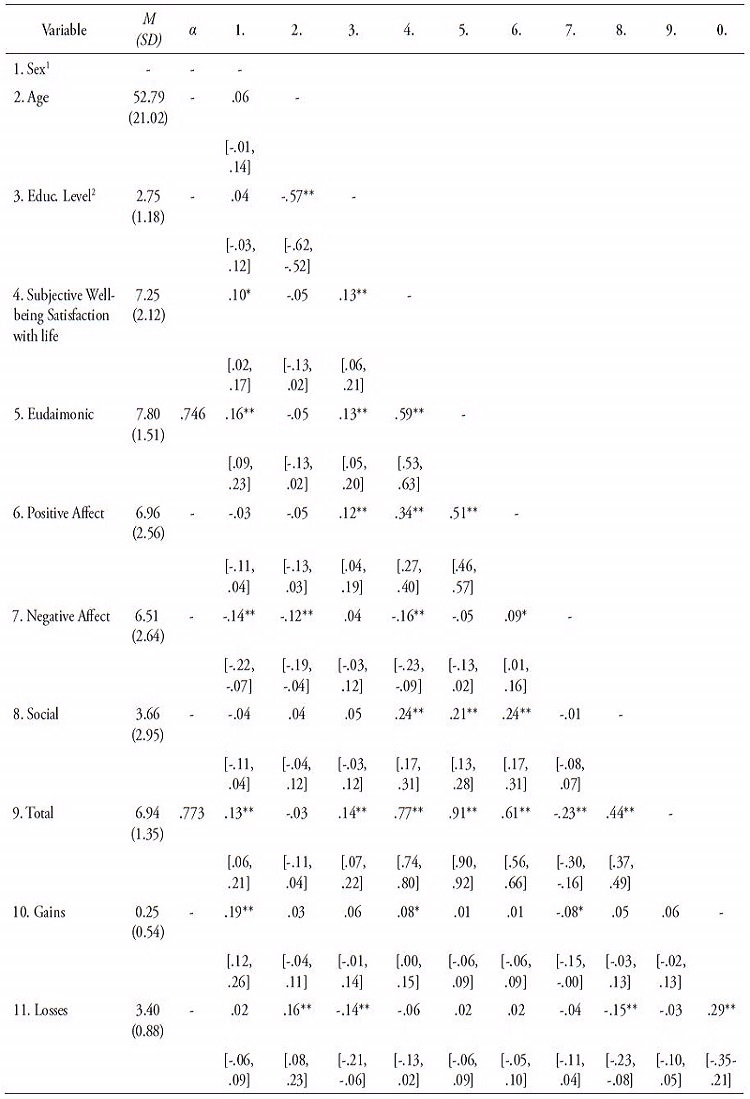

Events’ assessments and well-being. Finally, we conducted correlation analyses to explore how the psychological evaluations of socio-historical events affects individual’s well-being -correlations are presented in Table 7 (See Appendix. Losses were negatively related to the item of social wellbeing, r = -.15, and gains were related to satisfaction with life r = .08 and to low negative affect r = -.08.

Table 7 Descriptive and Correlations between Well-being Dimensions and the Evaluations

Note. M(SD) indicate Means and Standard Deviations, respectively. 1, sex was represented by 1 = woman, and 2 = men. 2, Educational Level measured with 4 levels. Values in square brackets indicate the 95% confidence interval for each correlation. *, p < .05; **, p < .01.

Discussion

Eight of the ten most mentioned events are strictly related to violent acts perpetrated on a particular individual or to armed conflicts, such as the Gulf War, or the internal division that triggered a civil war. Observing their characteristics, most of historical events correspond to local or regional events - i.e., having occurred in Palestine and/or Israel, and having produced direct consequences to the Palestinian. On the one side, this pattern is partially similar to the findings from Latin American countries where the CEVI project has taken place (e.g., Concha et al., 2009; Oddone & Lynch, 2010; Paredes & Oberti, 2015), in comparison to those from Europe, where there were higher frequencies of international events (see Cavalli, 2016). Specifically, these data suggest, besides the local predominance, that Palestinians do mention international events; nevertheless these are not events mentioned at the global level, but rather international events that have had a more direct impact on the Arab world (e.g., Saddam Hussein’s execution, the Suez Channel Crisis). In other words, the Palestinians’ social representation of its own history is idiosyncratic, insofar as the most salient events in their memory are centered in their cultural area or region, as has already been seen in other regions further east (see Liu et al., 2005). On the other hand, it is worth noting the shared-element of political conflict and permanent struggle, represented by Palestinian society. Events such as the First intifada may fulfill an identity and cohesive function in a society with a social representation of its own history based on the suffering of the in-group, and can be socially represented in a positive way.

As it can be seen, the assessments of gains - which on average is 0.25, for up to four mentioned socio-historical events - relate to more different domains of well-being. Namely, it relates to general and affective well-being. Conversely, the assessment of losses - on average, more than 3 -, only relates (negatively, and being the greater correlation) with the social aspect of well-being, which is the only dimension with a mean that is under the mid-point of the theoretical scale (M = 3.68, from in a scale from 0 to 10).

Conclusion

By respect to the content and regularities of collective memory, the predominance of collective violence and political-military contents of the events was confirmed. In line with previous studies and reviews, and using a life course approach, CEVI studies show the high prevalence of the topics of politics, collective violence and warfare. Although some studies have found a bias towards violence and negativity, our results show that collective memory have an ambivalent content, negative valence events being less than half of recalled events. Political, social and technical events of positive valence accounted for about half of the collective memory content. Further, and even though there is a tendency to appraise sociopolitical events as positive or partially positive, an important caveat in Palestine was that most of the events were entirely or partially negative. Among them were those related to fights and sufferings, reflecting the reality of a society immersed in a long-term strong sociopolitical conflict with Israel.

Socio-centrism of collective memory or the bias to mention of events linked to the nation of belonging was also confirmed. On the other hand, previous studies suggest to some extent a West-centrism bias. Non-national or international events recalled tended to be related to the Western culture. In Latin American nations and Palestine, however, the results showed a socio-centric pattern. Particularly in Palestine, no Western events were mentioned, and most of events were national or related to Palestinian in-group. The international events that were mentioned occurred in nearby countries, and could be perceived as of greater importance to the Arabic-speaking world. This “regionalism” was not observed in Latin America, for instance, but it was present in the collective memory of newly decolonized nations such as Angola and East Timor, in which people essentially report as historical events those related to national fight for independence and the construction of nation-state (Cabecinhas et al., 2011). Nevertheless, we consider that future studies from different parts of the world would clarify the relations between national contexts and social representations of history.

Concerning the age, nine reviewed CEVI studies, as well as the particular case of Palestine, confirm the generational or cohort effect. A meta-analysis of CEVI studies confirm a significant effect of critical period (see Páez et al., 2018), which can also be clearly seen 24 of the 100 most mentioned events in the CEVI studies presented here, including the results from Palestine. Conversely, this revision also shows that half of the ten most mentioned events have a greater probability of being mentioned by different generations that were alive during the event. This period effect has also been found in previous research and, like those studies, the Palestine data suggest that these events share common features, such as the social importance for the in-group and the high-intensity of emotional load.

We also found that different evaluations of the events (as gains or losses) were associated with different effects on the well-being. This is an important result because, once again, it shows that the content of collective memory and not only of personal life events (Méndez et al., 2018) has an influence on well-being. Another interesting point is that positive historical events show a larger influence than negative ones on personal well-being - i.e., negative events were associated only with low social well-being. Even though additional analyses might be needed (considering the role of others as well, such as gender, political positioning, age, etc.), these results highlight the relevance of people’s resilience and their skill to cope and deal with negative macrosocial events.

Interestingly, we found gender differences between the kind of events women and men recalled in Palestine. In particular, when the variable explained the probability of mention, women tended to mention more events of war and collective violence (e.g., Gaza War or Al Asf Al Macul [the 53-day siege in Gaza]), whereas men tended to mention more internationally relevant events (Saddam Hussein’s execution and Naksa Day). As a possible explanation, this difference may be due to the lower participation of women in the politic life in Palestine, and to the fact that many of them reported having lost son and daughters in these events. We believe it would be of great interest to investigate these relations in more detail within conflictive but more gender-egalitarian societies.

Finally, it should be noted that some recent events were highly cited in the Palestine case. It could be that a recency effect - also observed in other studies on social representations of history - is stronger for events in conflictive contexts. Because their emotional impact may be fresh in the minds of the participants, excessive recall of these events may have no real relevance to the historical narrative. With this in mind, it would also be interesting to explore possible differences between free recall and closed-list approaches. The recall of personally experienced historical events represents the very first step to the construction of a social representation about it. CEVI studies on collective memory allows understanding this basic process, its similarities and differences between societies, and its transformation throughout generations. The evaluation of the links between collective memory, social representations of history, and emotions represents a promising field of research to advance the theory of social representations.

Study limitations and future directions

This research work presents a notable limitation common to all the studies analyzed: the maximum quota of four memories established by the CEVI protocol. On the other hand, the PHI well-being indicator used for the correlational analyses in the Palestine study, measures the social facet of the construct through single-item and does not comprise the total number of dimensions established by Keyes (1998), but assesses the general perception of living in a society that allows the individual to develop fully. Likewise, the CEVI protocol does not include indicators of social identity or subjective social class, considered essential factors that influence autobiographical and collective memory (Liu, 2022).

Future directions would be to combine free-recall tasks with those of recognition of a closed-list of events, and to analyze brief indicators of identification with ethnic and national social groups, political beliefs (RWA, SDO and system justification), income and subjective social class.

Funding

This research work was granted with a predoctoral fellowship from the Department of Education of the Basque Government (PRE_2017_1_0405) to Lander Méndez, as well as by funds granted to the Research Group: Culture, Cognition and Emotion (CCE), by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Ref. PID2020-115738GB-I00), and by the Basque Government (Ref. IT1598-22). This investigation was also partially supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation [Ref: 100017_132047].