INTRODUCTION

Pneumobilia is the presence of gas in the biliary tree. 1,2 In most cases, it is related to cholecystoenteric fistulas of biliary origin, emphysematous cholecystitis, surgically created anastomosis between the intestine and the extrahepatic biliary tract, endoscopic interventions, and dysfunction of the sphincter of Oddi. 3,4 Traumatic etiology has been associated with pneumobilia and there are few reported cases related to closed thoraco-abdominal trauma 5.

It is usually a benign condition; however, it can be life threatening when it is due to an emphysematous infectious process, (6 or in relation to the compromise of other organs injured in the trauma. We present the case of a patient who, after a closed thoracoabdominal trauma, presented rib fractures, concomitantly with pneumoperitoneum, pneumobilia and pneumowirsung, receiving conservative management. He had a favorable clinical course.

CASE REPORT

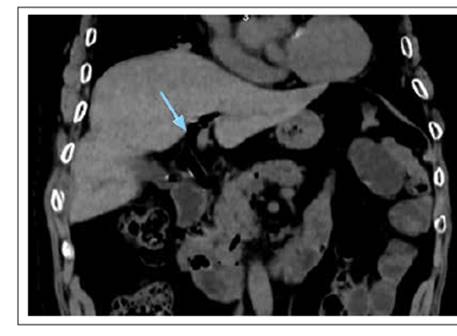

A 75-year-old male patient suffered a fall in the bathroom, hitting his right rib cage. He presented pain in that area that increased in intensity over the next two days, despite self-medication with analgesics. He went to an urgent care center, where a chest X-ray was taken, which revealed pneumoperitoneum and a right rib fracture, (Figure 1) for which he was referred to a third-level Hospital, where he was admitted on February 10th, 2022.

Figure 1 Chest X-ray showing pneumoperitoneum (blue arrow); also, traces of right rib fracture and left basal atelectasis.

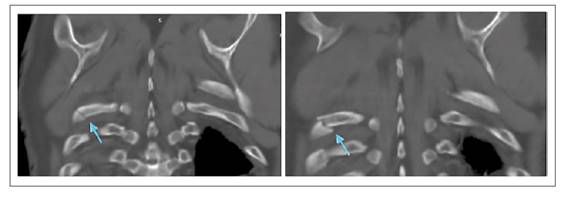

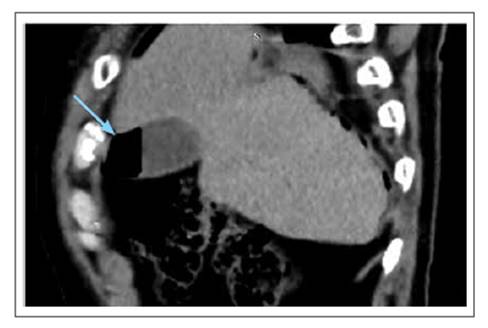

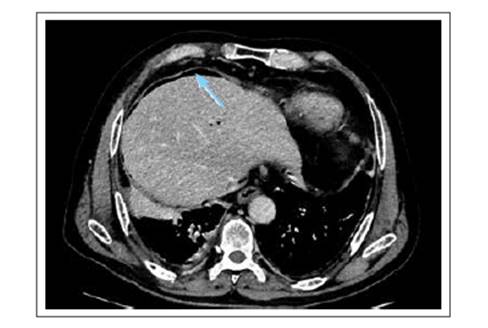

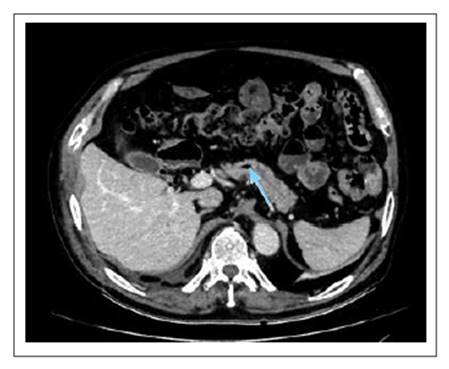

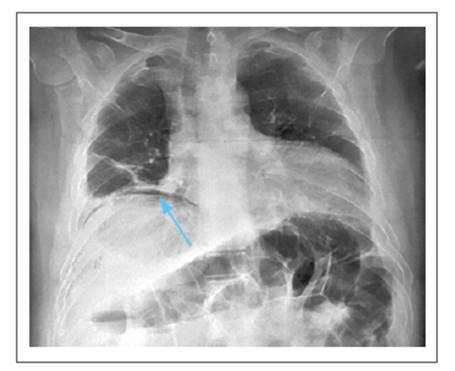

The patient had no pathological or previous surgical history, and denied a history of gallstones. He arrived at the hospital hemodynamically stable, with moderate intensity pain in the costal region and right upper quadrant, which was intensified by inspiration. Laboratory tests were performed, all within the normal range. Thoracic and abdominal CT scan with contrast showed fracture of the 8th, 9th, and 10th right costal arches (Figures 2-3), gallbladder wall rupture (Figure 4), pneumobilia (Figure 5), pneumoperitoneum (Figure 6), and left basal pulmonary atelectasis. It was decided to start antibiotic treatment upon admission to the hospital.

During his clinical evolution, the patient presented oxygen desaturation, for which he was started on binasal cannula oxygen therapy. He received respiratory physiotherapy and continued with the established antibiotic treatment. Surgical expectant management was chosen.

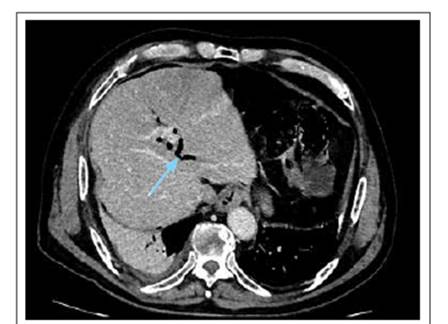

On the 6th day of hospitalization, there was a decrease in thoracic and abdominal pain; likewise, the patient required less oxygen supply, starting oxygen weaning. Abdominal CT scan on the 10th day of hospitalization showed resolution of the pneumoperitoneum, but persistence of pneumobilia (Figure 7), and air was also found in the pancreatic duct of Wirsung (neumowirsung). (Figure 8)

A decision was made to keep the patient under observation and continue to provide conservative management, in conjunction with general surgery. On the 16th day of hospitalization, the patient did not present abdominal or chest pain. In addition, he was weaned off oxygen with good tolerance. His hospital course was uneventful, and he was discharged without complications.

DISCUSSION

Pneumobilia is defined as the presence of air in the biliary tree and implies an abnormal connection between the gastrointestinal and biliary tracts. 3 The most common cause includes the presence of gallstones and consequently biliaryenteric fistula. 1 Of these patients, up to 50% may present with pneumobilia. 7 It can also occur after a biliary- enteric anastomosis or manipulation of the bile duct in endoscopic procedures, such as ERCP, especially in cases in which sphincterotomy is performed, 1)(7)(8 a procedure creating incompetence of the sphincter of Oddi. 4 Other less common causes include malignant processes such as lymphoma of the duodenal papilla. 9

The presence of pneumobilia without any intervention or procedure suggests an infectious process, such as emphysematous cholecystitis, pyogenic cholangitis, or an abnormal biliaryenteric connection that requires surgical management. 7 In the case presented, the patient had no history of manipulation of the bile duct, either surgically or endoscopically, nor a history of gallstones. In addition,the abdominal ultrasound and abdominal tomography did not show cholelithiasis that could lead to a biliaryenteric fistula.

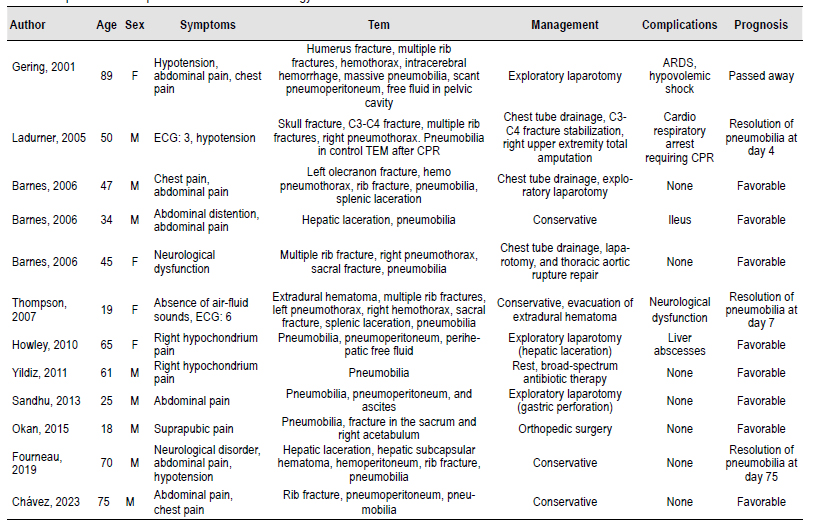

Some other etiologies for the development of pneumobilia are considered, especially trauma related. The development of pneumobilia is extremely rare after closed abdominal trauma 7,8), with a few cases reported to date. The patient we report fell while taking a bath. It is worth mentioning that most of the reported cases presenting with pneumobilia were the result of a high-impact abdominal trauma after a traffic accident, with multiple organic compromise.

It is known that the sphincter of Oddi can support a pressure of up to 60 cm H2O, thus preventing the passage of air into the biliary system. 2)(10 From a pathophysiological standpoint, post-trauma pneumobilia is the result of retrograde passage of air from the proximal intestinal lumen to the sphincter of Oddi and the biliary system, due to increased intra-abdominal pressure. 3)(7)(11 The same pathophysiological mechanism has been described in a reported case of pneumobilia after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. 12 We agree that this mechanism explains the presence of pneumobilia in the case presented, having closed thoracic-abdominal trauma as the sole associated factor. Unlike the cases reported to date, our patient also presented pneumowirsung (Figure 4), which supports the theory of retrograde air flow through the sphincter of Oddi, not only to the biliary system but also to the pancreas. In the literature, the presence of pneumowirsung has only been reported in association with postoperative patients, 13 but not as a result of thoraco-abdominal trauma.

Pneumoperitoneum in blunt abdominal trauma is usually associated with hollow viscus perforation. 8 In the case reported, in addition to pneumobilia, the patient had pneumoperitoneum. Despite the presence of rib fractures, no pneumothorax is evident. One possible mechanism to explain pneumoperitoneum could be related to the rupture of the gallbladder wall that was in contact with the area of the rib fracture. In the case reported by Howley et al. 8), pneumobilia plus pneumoperitoneum is reported, and it is considered that the intensity of the abdominal trauma caused retrograde passage of air through the sphincter of Oddi and was strong enough to cause rupture of the hepatic capsule, causing leak into the peritoneal cavity. The patient, they reported, later developed hepatic abscess formation, which supported this theory.

Rib fracture is a frequent finding in reported cases of neumobilia which can be associated with other complications such as pneumothorax or hemopneumothorax. 10-11 In the case we report, there was a triple rib fracture and despite the fact that the patient needed oxygen support through a binasal cannula, no hemorrhage or pneumothorax was reported; rather, pulmonary involvement was due to left basal atelectasis.

Pneumobilia can be diagnosed with the support of a simple abdominal X-ray, abdominal ultrasound, or MRI 1), but CT scan is the most sensitive and specific method, being utilized in all reported cases including ours. 2-3

Prompt diagnosis and early management of traumatic pneumobilia are necessary to minimize morbidity and mortality associated with causes requiring surgical treatment. 6 Of the eleven cases reported to date, only one had a fatal outcome. 11 The other cases had some sequelae, but these were due to complications more related to great impact traffic accidents than to pneumobilia itself.

There is no consensus regarding the management of pneumobilia, since it should be approached on a case- by-case basis. For instance, Sandhu et al. performed an exploratory laparotomy for pneumobilia and pneumoperitoneum caused by a gastric perforation 3). On the other hand, Howley et al. reported hepatic laceration associated with pneumoperitoneum and pneumobilia. 8 We decided to take a conservative approach with clinical and imaging control. The patient presented spontaneous resolution of the pneumoperitoneum on the 10th day, although pneumobilia and pneumowirsung persisted.

In our case, due to hemodynamic stability and an abdomen without peritoneal signs since admission, it was decided to maintain conservative management with antibiotic therapy. In addition, in the second tomography pneumoperitoneum was no longer present, so it is considered that a gallbladder plastron occurred, which explains the good clinical evolution of the patient without the need surgical intervention. Therefore, pneumobilia of traumatic etiology would not be an indication for surgical management per se.

Author Age Sex Symptoms Tem Management Complications Prognosis

CONCLUSIONS

Closed thoracic-abdominal trauma can cause pneumobilia, pneumoperitoneum, and pneumowirsung. These diagnostic possibilities should be considered in the absence of pathological history or previous procedures. In addition, surgical management will not always be required, as long as the patient is kept under permanent observation and the pertinent control imaging study is performed.