INTRODUCTION

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is an inflammatory condition of the pancreas usually caused by bile stones or alcohol. While in most cases the disease takes a mild course, around 20% of patients develop a severe form, often associated with single or multiple organ failure requiring intensive care, where the management of hydration, pain relief and early enteral nutrition are the mainstay of treatment 1-3.

Enteral nutritional support has been found to limit complications and improve outcomes in patients with severe acute pancreatitis 2. Maintaining enteral nutrition is thought to help preserving intestinal barrier function and reducing bacterial translocation, thereby reducing the risk of infected peripancreatic necrosis and other serious outcomes 3.

Previously, enteral feeding via nasojejunal (NJ) tube was the preferred approach because it allowed the pancreas "to rest", but its benefits over nasogastric (NG) feeding are unclear 3,4. However, inserting NJ tubes requires radioimaging or endoscopy that could delay the starting of feeds. NG tubes are technically easier to insert and their use can prevent delays in initiating feeds.

There are few trials that specifically addressed the issue of NG vs NJ feeding in AP. Therefore, we performed a systematic review to evaluate the efficacy and safety of enteral feeding with a NG tube vs. NJ tube in patients with severe acute pancreatitis.

METHODS

Search Strategy

We conducted a comprehensive literature search in PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Embase, without language limitation until December 1, 2022. We also searched reference lists of all included studies and relevant review articles to identify other potentially eligible studies. Duplicated data found across the databases were removed. A complete detail of the search strategy can be found in supplementary data.

Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

Two independent reviewers (AC, HB) assessed titles and abstracts for eligibility according to the inclusion (full reports of randomized controlled trials [RCTs] comparing enteral feeding by NG and NJ tubes in patients with severe AP) and exclusion criteria (conference abstracts, RCTs in children, observational studies, editorials, systematic reviews, and narrative reviews). The same two reviewers independently evaluated the full-text of studies and registered reasons for the exclusion. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data Extraction

Data for each study was extracted by two review authors (AC, HB) independently. A third reviewer (AP) was consulted to resolve discrepancies. Extracted data included: general information (journal title, year of publication, author names and contact information); methods (diagnosis of AP, severity assessment of AP, random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, follow-up); participants (country, age, gender, comorbidities, nutritional status); interventions (method of NG and NJ tube placement, position of NJ tube in relation to ligament of Treitz, interval from admission to intervention, number of participants in each arm); outcomes per arm (pre-specified primary and secondary outcomes); and additional information (funding, conflicts of interest, trial registration).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes included rate of infection, organ failure, number of complications (aspiration, diarrhea, bloating, sweating, or vomiting), length of hospital stay (LOS), surgical intervention, and duration of tube feeding. We used definitions provided by authors.

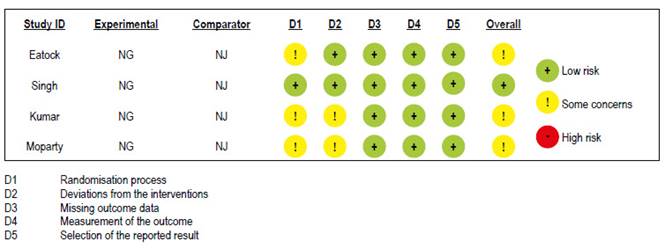

Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias (RoB) assessment was done independently by two investigators (AC, HB) using the Cochrane RoB 2.0 tool for RCTs 5. A third reviewer (AP) was consulted to resolve discrepancies. The RoB 2.0 tools assesses five domains of sources of bias: randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, and selection of the reported result. Each domain is rated at low risk, high risk or some concerns of bias, according to a pre-defined algorithm of the tool, which is based on the responses to signalling questions within each domain. Then, each RCT was rated as high RoB if at least one domain was at high RoB; as some concerns of bias if at least one domain was at some concerns of bias and there was no domains at high RoB; and as low RoB if all domains were at low RoB.

GRADE certainty of the evidence

The certainty of evidence (CoE) was evaluated using the GRADE methodology (www.gradeworkinggroup.org 6. The CoE per outcome was based on the evaluation of five areas: RoB, inconsistency, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias. Description of CoE was presented in summary of findings (SoF) tables using the GRADE pro software (McMaster University and Evidence Prime, 2021; www.gradepro.org/).

Statistical Analysis

The systematic review was reported according to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines 7. We performed random effects model for all meta-analyses using the inverse variance method. Paule-Mandel method to calculate the between study variance (tau2) and the Hartnung-Knapp adjustment of 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used. Effect measures were reported as relative risks (RR) and their 95% CIs for dichotomous outcomes and mean difference (MD) and their 95% CIs for continuous outcomes. Heterogeneity of effects was evaluated using the chi2 test (threshold < 0.10). I2 statistic, with values of <30%, 30-60%, >60% corresponding to low, moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively. Sensitivity analysis was conducted including only RCTs with low risk of bias. All analyses were performed in R 3.6.3 (www.r-project.org).

RESULTS

Study selection

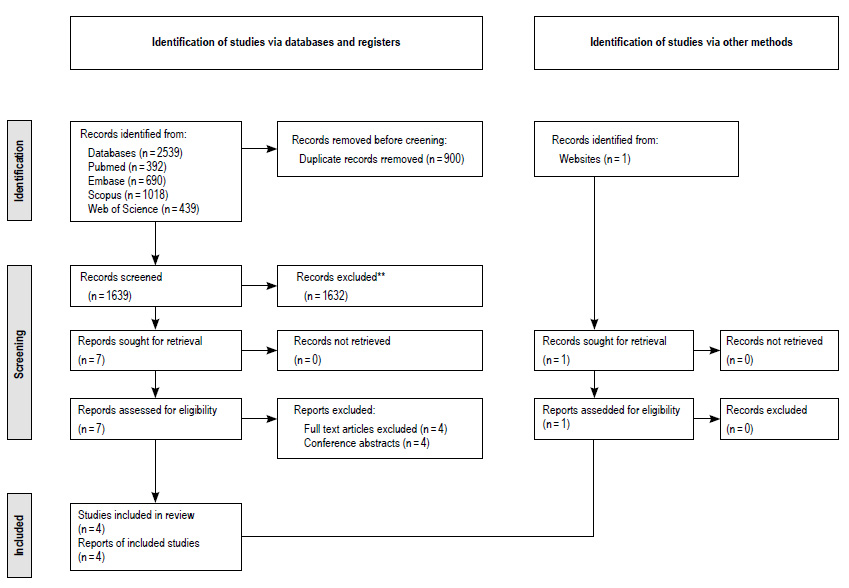

Our search yielded 2539 records. After the removal of duplicates, the abstracts of 1639 articles were assessed for eligibility according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria: 900 articles were excluded. After full-text assessment of seven remaining articles, four were excluded for being available only as abstracts from conference presentations. One source was identified by manual search. Finally, four RCTs 8-11 were selected for analyses (Figure 1).

Study characteristics and demographics

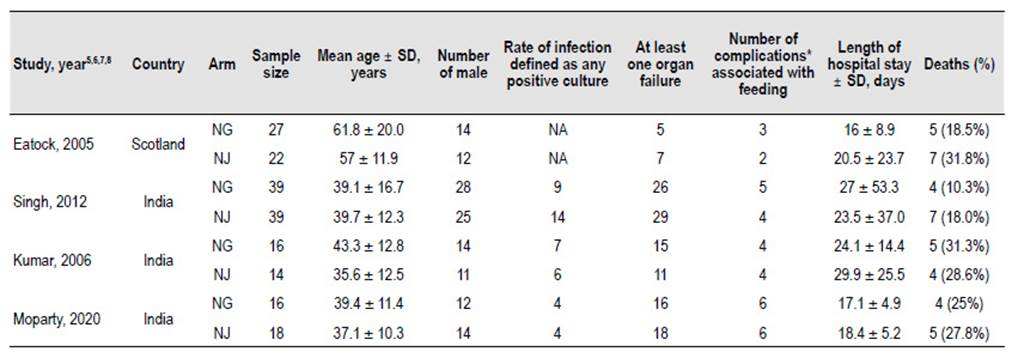

The main characteristics of the four RCTs are summarized in Table 1. These studies included 192 patients with severe AP with mean ages that ranged between 35.6 and 61.8 years old. Three RCTs were conducted in India 9-11 and one in Scotland 8.

Table 1 Characteristics of the included randomized controlled trials in severe acute pancreatitis.

NG, nasogastric; NJ, nasojejunal; NA, no available; *, Complications included: aspiration, diarrhea, bloating, sweating, or vomiting.

Kumar et al. recruited 30 participants for 15 months 9, Singh et al recruited 78 patients for three years in a noninferiority RCT10 and Moparty et al.11 recruited 34 patients in two years. The Scotland study was done by Eatock et al. 8 who recruited initially 50 patients for three years, but one patient had false diagnosis in the NJ group.

All included studies were made in patients with severe AP but the criteria used were not the same in all RCTs. The severity criteria used by Eatock et al.8 was Glasgow prognostic score ≥3, APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation) score ≥6, or C-reactive protein >150 mg/L. Kumar 9 and Singh 10 used the same criterias: one or more organ failures as defined by Atlanta criteria (1992), APACHE II score >8 and/ or computed tomography severity index (CTSI) >7; while in the most recent study conducted by Moparty et al.11, the revised Atlanta Classification (2012) was used. However, if we use this last classification in the participants of the previous studies, the majority would have SAP.

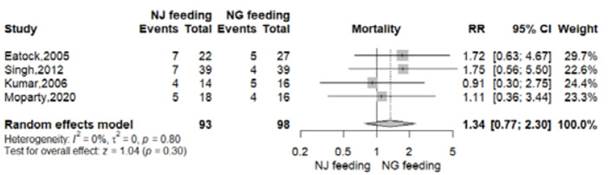

All-cause mortality

There were 18 deaths in 98 patients from NG group (18.3%) and 23 deaths in 93 patients from NJ group (24.7%)8-11. There was no significant difference in all-cause mortality between the nasogastric and nasojejunal feeding arms (RR=1.34, 95% CI 0.77-2.30; p=0.30; I2 = 0%, Figure 2, Table 2).

Figure 2 Effect of nasogastric versus nasojejunal tube feeding on all-cause mortality in patients with severe acute pancreatitis.

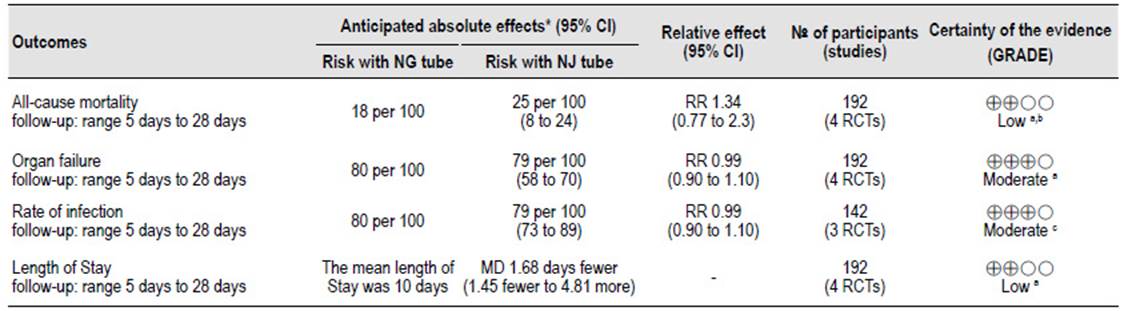

Table 2 Summary of findings of quality of evidence of primary and secondary outcomes.

NG, nasogastric; NJ, nasojejunal; RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval; MD, mean difference.

a. RoB: Eatock, Kumar and Moparty had some concerns at risk of bias, Singh had low risk of bias.

b. Imprecision: 95% CI 0.31-2.84.

c. RoB: Kumar and Moparty had some concerns at risk of bias, Singh had low risk of bias.

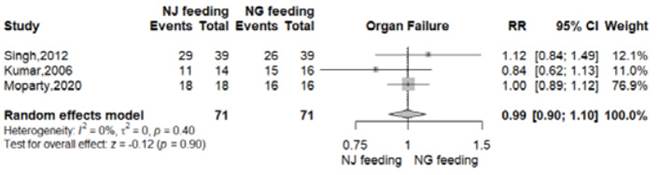

Organ failure

At least one organ failure was reported in 57 of 71 patients from NG group (80.2%) and 58 of 71 patients from NJ group (81.6%) 8-11. There was no significant difference between the nasogastric and nasojejunal feeding arms (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.90-1.10; p=0.90; I2 = 0%, Figure 3, Table 2).

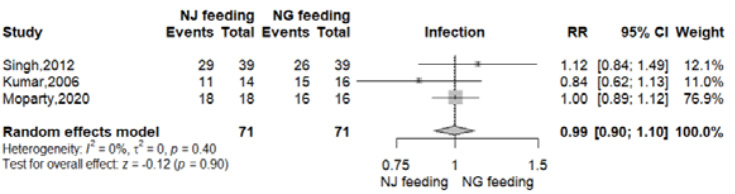

Infection

Data for this outcome was reported in three RCTs 9-11. Infection with positive culture was reported in 57 of 71 patients from NG group (80.2%) and 58 of 71 patients from NJ group (81.6%). There was no significant difference between the nasogastric and nasojejunal feeding arms (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.90-1.10; p=0.90; I2 = 0%, Figure 4, Table 2).

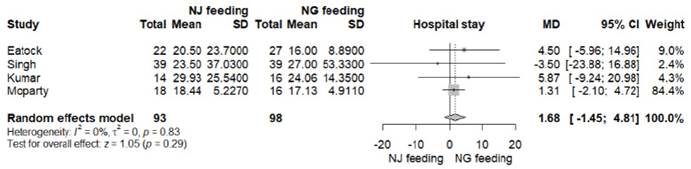

Length of hospital stay

Data for this outcome was reported in all RCTs 8-11. LOS was lower in the nasogastric feeding arm in the studies of Eatock and Kumar, but the differences were not statistically significant. In the final analysis, there was no significant difference between both feeding arms (MD -1.68 days, 95% CI -1.45 to 4.81; p=0.29; I2=0%, Figure S1, Table 2).

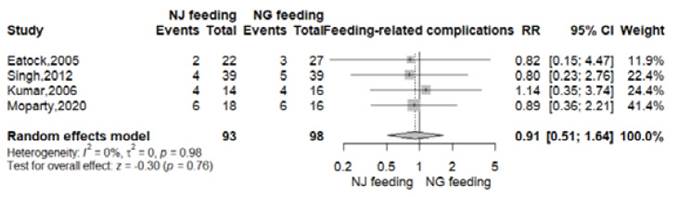

Feeding related complications

Feeding related complications like diarrhea, bloating, vomiting, palpitations or sweating were reported in 18 of 98 patients from NG group (18.3%) and 16 of 93 patients from NJ group (17.2%) 8-11. There were no significant differences between the nasogastric and nasojejunal feeding arms (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.51-1.64; p=0.76; I2 = 0%, Figure S2).

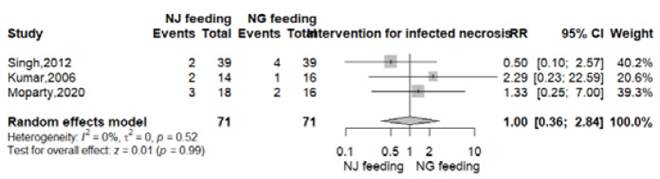

Intervention for infected necrosis

Data for this outcome was reported in three RCTs 9-11. Intervention for infected necrosis were surgical or endoscopic and were reported in 7 of 71 patients in both groups (9.8%). There was no significant difference between the nasogastric and nasojejunal feeding arms (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.36-2.84; p=0.99; I2 = 0%, Figure S3).

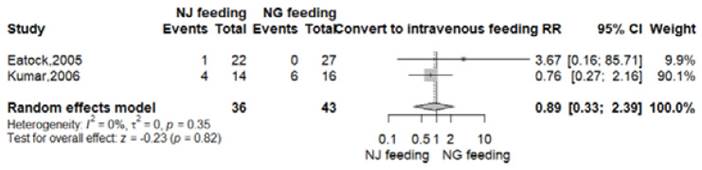

Convert to intravenous feeding

This outcome was reported in two RCTs 8,9. Convert to intravenous feeding was repoted in 6 of 43 patients (14%) in nasogastric group; meanwhile in the nasoyeyunal arm, 5 of 36 patients (13.8%) needed intravenous feeding. There was no significant difference between both groups (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.33-2.39; p=0.82; I2=0%, Figure S4).

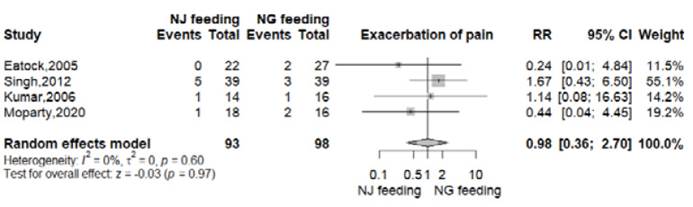

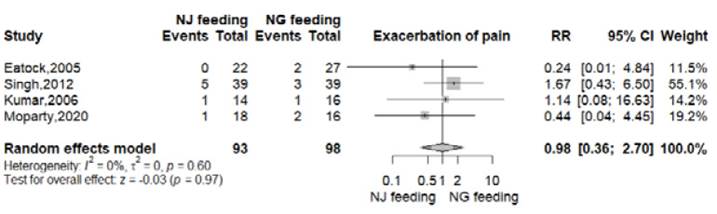

Exacerbation of pain

All RTCs reported this outcome 8-11. In the nasogastric arm, 8 of 98 patients (8.2%) presented exacerbation of pain. In the nasojejunal arm, this event was reported in in 7 of 93 patients (7.5%). There was no significant difference between both groups (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.36-2.70; p=0.97; I2=0%, Figure S5).

Success rate of procedures

Three RTCs reported this outcome 8-10. The success rate of feeding achieved in all patients of nasogastric group (100%); and in the nasojejunal arm, the success rate was reported in 74 of 75 patients (98.6%). There was no significant difference between both groups (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.95-1.03; p=0.64; I2=0%, Figure S6).

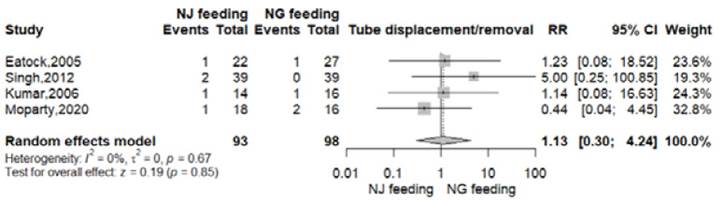

Tube displacement/removal

All RTCs reported this outcome 8-11. In the nasogastric arm, this event took place in 4 of 98 patients (4.1%); meanwhile in the nasojejunal group 5 of 93 patients (5.3%) presented tube displacement or removal. There was no significant difference between both arms (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.30-4.24; p=0.85; I2=0%, Figure S7).

Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias assessments of RCTs are shown in Figure S8. One study had low risk of bias 10 and the other three 8,9,11 had some concerns with randomization process and deviations from the intended interventions.

GRADE summary of findings

Organ failure and reate of infection had a moderate certainty of the evidence. All-causa mortality and LOS was judged as low certainty of the evidence (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In our systematic review of 4 RCT 8-11, we found as our primary outcome that there were no statistically significant differences between the use of NG and NJ tube for allcause mortality in severe AP. As with the primary outcome of mortality, there was no evidence of superiority with NG or NJ feeds on any of the secondary outcome reported. The success rate and complications of the procedure were similar. The rates of organ failure, infection, tube displacement/removal, exacerbation of pain, convert to intravenous feeding, duration of tube feeding and length of hospital stay, were also similar in the two groups. There was no significant diference in the requirement of intervention for infected necrosis, surgical or endoscopic. Three of the four RCTs had some concerns of bias 8,9,11. The certainty of the evidence ranged between moderate to low (Table 2).

What we know about the research question

AP is an inflammatory condition of the pancreas and its severity ranges from mild to severe. Early recognition of severity allows optimization of management, which includes nutritional support.

Enteral nutrition has been established as a mainstay of severe AP treatment due to the deficit generated by the hypermetabolic state associated with the disease. This route of nutrition has been proven to present fewer complications and potential better effectiveness than parenteral nutrition, as preservation of intestinal mucosal integrity and limitation of bacterial translocation 12.

Nasojejunal feeds were established early in severe AP management due to the belief that feeds distal to the duodenum-jejunal flexure would not stimulate the pancreas and reduce the risk of inflammation exacerbation by exocrine secretion. However, animal studies later indicated that pancreatic exocrine secretion under stimulation of cholecystokinin is suppressed in AP suggesting that NJ approach has potentially no benefits over a NG approach 13. In addition, a great advantage of the use of the NG tube is its easy placement, thus avoiding the need for an endoscopy or radiological support, thus reducing the risks associated with these procedures and the costs that they entail.

In a recently review, Dutta et al. found five RCTs with two studies only available as abstracts 4. Authors found that there was no evidence of differences of effect between NJ or NG tube placement on mortality. Also, there was no significant difference for the secondary outcomes: organ failure, rate of infection, success rate, complications associated with the procedure, need for surgical intervention, requirement of parenteral nutrition, complications associated with feeds and exacerbation of pain. But the certainty of the evidence for these all outcomes was very low due to indirectness and imprecision.

What our study adds to the literature

Comparing with the most recent systematic reviews 14-17, our study included only RCTs with available full texts, which gave us complete information for assess risk of bias and analyse all outcomes. Also in some previous studies, patients who had moderately acute pancreatitis may had been considered as having severe AP because authors used old classifications to establish severity; therefore, the comparisons between NG nutrition and NJ nutrition could be biased. In our study, we used the Atlanta 2012 clasification criteria to classify severy AP by severity.

We used the Cochrane RoB 2.0 (version 2) tool for RTCs to assess the risk of bias. Previous studies applied the first version of it, published in 2008, and the updated version published in 2011. But the RoB 2.0 focuses in understanding how the causes of bias can influence study results, and the most appropriate ways to assess this risk. Compared to previous reviews, we applied the GRADE tool to rate the certainty of evidence. However, our study has some limitations. First, there were few RCTs that evaluate the use of NG vs. NJ tube in the management of severe AP. Furthermore, these RCTs included small samples. Second, most of the RCTs come from a single country and are unicentric. Third, the definitions of severity have varied over the years and in our review the definitions proposed by each study were used, which may increase the bias of our analysis. Therefore, it should be proposed to have more RCTs, including a larger sample, ideally multicenter, and with updated definitions of severity in order to compare the usefulness of NG and NJ nutrition.

In conclusion, in patients with severe AP, enteral feeding delivered by NG tube was as efficacious and safe as NJ tube. There were no differences in all-cause mortality or in the secondary outcomes. Further randomized controlled trials with more participants and better design are needed to confirm these findings.