Background of the study

While watching Whiskey Tango Foxtrot starring Tina Fey in the lead role, and directed by Glenn Ficarra and John Requa, the movie showed challenges journalists face in covering military operations in Afghanistan and how some lost their lives or body parts in the course of breaking the next story. I tried to imagine the same journalists in Nigeria reporting the insurgency in the northeast of such country, where the Boko Haram militant group has been fighting the Nigerian government since 2009 (Ahokegh, 2012). In Whiskey Tango Foxtrot, it was commonplace for female journalists to be in the field covering military operations. Can the same be said for Nigeria’s conflict areas especially with how deadly and violent the Boko Haram militant group has become? This study documents the contributions and representations of women in newspaper reports about military operations against Boko Haram in the northeast of Nigeria. The rise of feminism, especially the #MeToo Movement at the global level, has created the need to better understand feminine aspects of societal issues.

The role and impact of women in the Boko Haram insurgency have been captured in a number of studies (Bigio & Vogelstein, 2019; OCHA, 2019; Okoli, 2019; Sunday, 2019; UNICEF, 2019; Pillay, 2018; Idowu, 2016; International Crisis Group, 2016; Mlambo-Ngcuka & Coomaraswamy, 2015; Okeowo, 2015 ). The conflict has had an astounding impact on the lives of thousands of women (and girls): some have been recruited voluntarily, and others by force or for lack of other options into new, evolving roles outside the domestic sphere. Others joined the group first as members of a religious community and later as insurgents, while many are targets of its pugnaciously sinister and brutal campaign. Some fight against it within local vigilante units; others play critical roles in relief, rehabilitation and reconciliation efforts; while many displaced by fighting find themselves with new responsibilities in internally displaced people’s shelters or makeshift homes (International Crisis Group, 2016 ).

Women are mainly confined to a domestic role of bearing children as wives and being housekeepers; however, because of their ability to pass through military checkpoints, they have been increasingly used as suicide bombers targeting the military and public places of gathering like markets and motor parks. Extremist groups rely upon women to gain strategic advantage, recruiting them as facilitators and martyrs, while also benefiting from their subjugation. (Bigio & Vogelstein, 2019; Zena, 2019 ). Scholarships estimate that women represent between 10 and 15 percent of a terrorist group’s membership (Matfess & Warner, 2017), while many others have been fighting the terror group (Sunday, 2019; Idowu, 2016; Okeowo, 2015), and others have been providing humanitarian services and working in the media in the troubled region in the face of daunting impediments (Awokoya, 2019; OCHA, 2019; UNICEF, 2019 ).

In exploring the issue of women in journalism, York (2017) notes that although women have dominated journalism classes, men have dominated the profession practice of journalism: a fact that has been supported in a number of studies (Oppenheim, 2019; Guaglione, 2019; Deutch, 2019; Ponsford, 2017; Women Media Center, 2017; Joyce, 2014; Djerf-Pierre, 2007). Joyce (2014) declares that The New York Times had the fewest female bylines (31 percent) of the ten largest newspapers, The Chicago Sun Times published the most female bylines (46 percent), and The Washington Post had the third highest rate (41 percent). Guaglione (2019) states that 41.7 percent of newsroom employees are women.

In support of this, York (2017) hypothesizes that the smaller number of women journalists could be a result of any ‘schedule incompatible with family life, the lack of female leadership or the glass ceiling.’ She adds that they are leaving their profession after graduation or being pushed out due to sexism or discrimination, while men are receiving 62 percent of bylines and other credits in print, online, TV and wire news, and have 84 percent of the last century’s Pulitzer Prizes. Deutch (2019) reiterates that journalism remains dominated by male reporters and their male sources. These sources mean that issues would be seen from their perspectives, while underrepresenting the views of the opposite gender, which creates an issue of gender imbalance in reportage and, by implication, gender bias. When the topic under coverage entails violence and conflict, the number of women journalists is expected to further diminish due to the higher risks of injury, physical and sexual assault, and even death involved in covering such a beat.

Mirroring from her personal account as a reporter who has covered violent conflicts, Awokoya (2019) posits that female war correspondents face risks on the frontline that their male colleagues do not have to contend with; however, it does not mean that they can be easily defined by stereotypes. In the frontline, male and female correspondents, she argues, were tasked with the same responsibilities: they embedded themselves with guerrillas, endured shellfire, travelled in the same clothes for days, and listened to horrific tales of victims that need their stories shared. Furthermore, she restates that being a woman on the frontline takes a certain type of courage, because doing so bears certain risks: risks that may not be nearly so common for their male counterpart, most especially with sexual assault and harassment. In spite of these challenges, women bring in an ingredient that makes them indispensable when covering conflicts. Alexis Okeowo, a reporter who has written about Boko Haram when responding to questions by Awokoya (2019), opined that

‘Despite the extra troubles of being a female journalist or working abroad, I think female voices are so essential. There is something special about reporters who can find people that they can connect with in different ways than their male counterparts. It broadens the narrative and gives a dimension and a scope that would not be there if these stories were told by men.’

Female voices are important in journalism and, in Nigeria, their case may not be different as seen in earlier studies discussed. In hindsight, Amobi (2013) traced the prejudicial treatment of women back to the pre-colonial era with roots in traditional African culture, Christianity and Islam, which all preach about the virtue of submissiveness of women. This bias is extended to the treatment of women in the media where they are ignored, denied or made to be invisible. Fab-Ukozor (2004) adds that media reports are unbalanced against women, with little reporting about their issues except when they are presented as models in ads. His reason for this bias is that control of media is either by the government and media owners who are mostly men and, as such, would not be bothered about issues beyond their sphere. This is supported by the World Economic Forum (WEF)’s Global Gender Gap Report 2018, where Nigeria ranked 133rd out of 149 countries (Ayetoto, 2018), moving down from the 122nd position in 2017 and the highest ranking of 94th attained in the first edition in 2006 (Bakare, 2018). The most recent ranking in 2020 places Nigeria 128th out of 153 countries (WEF Report, 2020): a slight improvement, but a lot is still expected from the various stakeholders in order to reduce gender disparity, with the major challenges faced by women in Nigeria being sexism, sexual harassment, assault in the workplace and denial of promotion due to their gender orientation, most especially those reporting about violent conflicts from unstable areas.

In the midst of these challenges faced by women reporters and women in general during violent conflicts, this study aims to highlight the representation of women in the bylines and pictures that appear in news stories about military operations against Boko Haram in the northeast of Nigeria, and also evaluate the occurrences of sources mentioned in these reports by women. The following research questions guided the study:

RQ1: What images of women are depicted in pictures used in reporting military operations against Boko Haram?

RQ2: What gender peculiarities were observed in the journalists covering news stories about military operations against Boko Haram?

RQ3: What is the gender disparity in the sources cited in news stories about military operations against Boko Haram?

RQ 4: How are the women portrayed media in reports about military operations against Boko Haram?

RQ5: Are there incidents involving violence (arrest, kidnapping, sexual assault, physical assault, online hate speech) against female journalists covering military operations against Boko Haram?

The newspapers which are the focus of this study provide a platform where issues can be dissected and discoursed, breaking down and ascribing meaning to complex events in the process of providing more clarity to the reported events (Okon, 2013). During and in the aftermath of national and international conflicts, news organizations try to analyze and contextualize information, so readers can get a better grasp of the conflict in relation to the national and foreign policies of the government, as well as its wider implications for the citizenry (Okon, 2017; Alli, 2001). Four Nigerian national daily newspapers were purposively selected for this research: Vanguard, Premium Times, Daily Trust, and The Nation.

Feminist theories

Feminist theories, popularized in the late 1960s and 1970s, focus on examining and analyzing gender inequality in the society, deepen debate about how gender constitutes society and, in this study, addresses gender inequality associated with reporting about military operations against Boko Haram by Nigerian newspapers. They use the conflict approach to examine the maintenance of gender roles and inequalities. Feminist theories analyze women’s experiences of gender subordination, the roots of women’s oppression, how gender inequality is perpetuated, and offer differing remedies for gender inequality (Jones & Budig, 2008). This research considered Radical Feminist Theory and Feminist Muted Group Theory.

The Radical Feminist Theory considers the role of the family in perpetuating male dominance. This theory focuses on the subordination of women to men due to universal patriarchy that exists across all cultures and historical periods (Hines, 2008). According to radical feminists, it is sexism and patriarchy that explain the problem of women in society (Ityavyar, 1992). Radical feminists question why must women adopt certain roles based on their biology just as they question why men adopt certain other roles based on their gender. In patriarchal societies as those in Nigeria, men’s contributions are seen as more valuable than those of women. Patriarchal perspectives and arrangements are widespread and taken for granted. As a result, women’s viewpoints tend to be silenced or marginalized to the point of being neglected, discredited or considered invalid. Dow and Condit (2005) recognize the significance of feminist scholarship in the sense that it ‘sees itself as contributing to positive social change, creating a world in which there is greater gender justice’ (p. 461). Characterization of women in newspapers as this study researched is crucial for assigning power roles and exploring the roles that have been assigned to women when reporting military operations in the northeast of Nigeria.

The Feminist Muted Group Theory was propounded by Edwin and Shirley Ardener in 1975, and focuses on how marginalized groups (gender, race, social and educational status, etc.) are muted and excluded through the use of language (West & Turner, 2018). It was further developed by Kramarae (1981) in the field of communication studies. They suggested that in every society a social hierarchy exists, whereby certain privileges are granted to one group and not to the other. In this sense, the group with the advantage determines to a large extent the communication system for that society, and the muteness occurs due to the lack of power accorded to the group at the lower rung of the ladder (Amobi, 2013). Kramarae (1981) proposed that, to correct this imbalance, women must act similar to the dominant group (men) in terms of their perception toward things in the society.

Literature review

Gender in the Nigerian media has been treated by a number of scholars over time. Studies such as those by Nweke, 1989; Anyanwu, 2001; Okunna, 2002; Ashong and Betta, 2011; Nwabueze, 2012; Enwefah, 2016, among a host of others, explored the gender perspectives observed in the media landscape in Nigeria. In her findings, Nweke (1989) stated that statistics of the Nigerian media showed that there were no women among nearly 100 chief executives of broadcasting stations. She added that there were only three female editors and one acting editor among the 300 journalists of the Daily Times, with 75 being women. The News Agency of Nigeria (NAN) had eight women out of 127 journalists, with none occupying a senior management position. This was four years since the establishment of NAN; however, one woman sat on the ten-member board of directors of the agency.

She continued that, in the Federal Radio Corporation of Nigeria (FRCN), women made up 35 percent of the total workforce, and one woman out of six assistant directors was part of the senior management cadre. Exploring further, researchers like Ashong and Betta (2011) also had similar findings; they highlighted that men significantly outnumber women in all facets of communication practices in Nigeria. Whereas women constitute the majority of students of communication studies, men form the bulk of communication educators and practitioners in Nigeria. This was also affirmed by scholars like Anyanwu (2001) and Okunna (2002). The media landscape did not witness significant changes in the study by Enwefah (2016), who found out that females constituted 21 percent of newsroom staff in Nigeria, seven percent of the editorial staff and 25 percent of columnists.

Nwabueze (2012) investigated gender relations and representations in the Nigerian media. He rightly agreed that other studies have earlier established a lower number of female journalists and press underrepresentation of women. He observed that there is much less evidence that establishes whether there is a relationship between the lower number of female journalists and press underrepresentation of women. Using the newsroom ethnography method, he investigated female journalists’ perceptions of gender relation issues in the media with personal and group interview techniques. His findings showed that the low number of female journalists in Nigeria may be due to the optimum requirements and demands on female journalists who probably find it difficult to combine their career with domestic responsibilities that may be required from women, corruption and bias in the media, cultural factors and the fact that women do not want publicity. Another factor he ascribed for the underrepresentation of women was the male dominance of newsmakers in society. He recommended that women should aspire to positions of authority to become newsmakers, and effort should be made to ensure equality in gender representation in the media.

Methodology

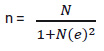

A content analysis research design was adopted, as this study was to analyze newspaper content. The research population consisted of four daily newspapers, which were purposively selected based on their spread and sphere of influence in the Nigerian media sphere, including Vanguard, Premium Times, Daily Trust, and The Nation. All the editions of the newspapers from January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2016 were taken into account. This gave us 365 days in 2014 and 2015 each, and 366 days in 2016, amounting to 4,384 issues in total. The sample size of this study was calculated using the Taro Yamane formula (Yamane, 1973) with a confidence level of 95%. The formula is as follows:

Where:

n = sample size required

N = number of people in the population

e = allowable error (%)

Thus, by substituting the values into the equation, this becomes

To ensure a uniform distribution across the issues, the sample size of 366 was reduced to 360. To account for an equal representation for each sampled newspaper, quota sampling was applied to share the sample across the newspapers into 90 issues for each sampled newspaper, and further divided into 30 issues per year for evenness. The unit of analysis for this study was straight news, and the study used both quantitative and qualitative techniques to analyze the data.

For a story from any of the sampled newspapers to be included as a unit of content, some keywords were chosen to guide their selection. At least one of them must have been included in the headline and the others must have been referenced in the body of the news account. Some of the keywords were army, military, troops, air force, soldiers, Special Task Force (STF), Joint Task Force (JTF), Defence Headquarters (DHQ), Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF), Nigeria, which were used with all or any of the following terms in the headline: Boko Haram, insurgents, terrorists, northeast, Borno, Yobe, Adamawa, Taraba, Bauchi, Gombe, woman, girl, lady, widow, daughter, mother, wife, grandmother, girlfriend. This definition reduced the burden of story selection.

Results and analysis

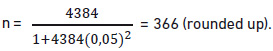

This research was carried out to explore the gender perspective in Nigerian newspapers’ reportage of military operations against the Boko Haram insurgent group. A total of 185 stories were coded and analyzed for this study from a sample size of 360 issues obtained from the four selected Nigerian national newspapers between January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2016. The analysis presented is based on news reports about military operations against Boko Haram in Nigeria. A further breakdown is presented in table 1.

Table 1 shows that Vanguard newspaper produced the highest number of stories with 62 (34%), while Daily Trust had the least number with 26 (14%). The lower number for Daily Trust could be attributed to the unavailability of some editions from the sample. The editions of Daily Trust not available were those from January 10, February 27, March 11 and May 10, 2014. The research sample is still valid because the four editions constitute about 4.4% of Daily Trust sample and 1.1% of the total sample population. One edition of The Nation dated June 27, 2014 was also not available. This underscores the need to have a good website that can archive issues over a long period of time. Vanguard and Premium Times have a very good website, with information stretching back to 2012 in the case of Vanguard. On the other hand, Daily Trust has changed its website between 2014 and 2016, which accounts for its lower data for the study.

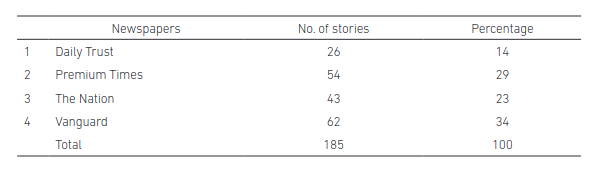

Research question 1: What images of women are depicted in pictures used in reporting military operations against Boko Haram?

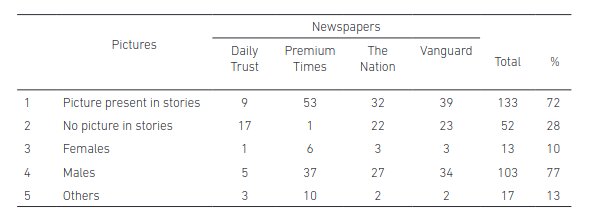

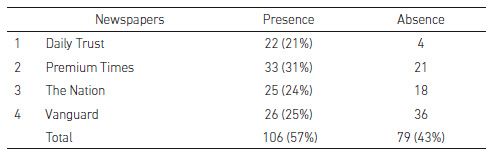

Table 2 shows that more stories with pictures, compared to those that had no pictures, were analyzed for the study. A breakdown of picture usage by newspaper shows that Premium Times used pictures in 53 out of the 54 stories selected, which translates to 40% of the total pictures used compared to Daily Trust which used the least with 9 (7%).

Females were seen in 10% (13) of the total number of pictures used in the stories captured by the study data, compared to males who appeared in 77% of the images and ‘others’ accounting for 13%. ‘Others’ could be military equipment or insignia, scene of a bomb blast or military activity. The result indicates that prominence is not accorded to women in the use of pictures as 10% is a gross underrepresentation. This stereotype was discussed in the Radical Feminist Theory, where the subordination of women by men is due to universal patriarchy (Hines, 2008). Men appeared in 77% of the images as soldiers fighting the insurgent group and rescuing women from Boko Haram captivity, providing donations for women (depicted as widows who have lost their men and now need the assistance of other men to survive), or running away from the conflict. On the other hand, women were presented as being helpless against the Boko Haram group, where only men could save them.

However, there are women serving as journalists, aid workers and volunteers whose stories have been muted. One challenge for this is to access to the conflict region. Most stories being reported from the conflict by Nigerian newspapers are either uncorroborated news from the military or stories from foreign news agencies, whose reporting agenda may not be the activities of female journalists, aid workers and volunteers in the conflict.

Images of women from Premium Times

For The Nation newspaper, the three images of women found in their reports were the same as those in Figure 6a (in two instances) and the image in Figure 6b.

Images of women from Vanguard

Source: Vanguard

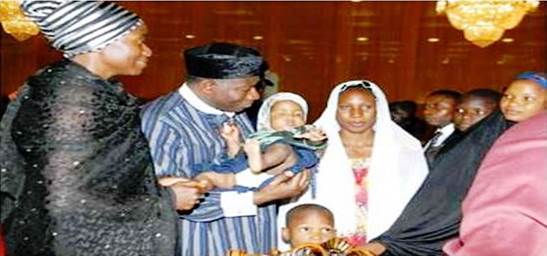

Figure 7 Former President Jonathan hosts widows and children of soldiers killed by Boko Haram

The next image is the same as the one used in Figure 5. And finally:

Judging from the images associated with women in the news reports, they are considered as being vulnerable, prone to be kidnapped―even though the insurgents kidnap both men and women―, or rescued from Boko Haram. No image depiction focuses on men being rescued the way attention is given to women being rescued. This description portrays women as being weak, being prone to be kidnapped, and needing men to rescue them from captivity. This may not be the entire truth as women have been shown to be humanitarian workers, journalists and soldiers involved in the fight against the insurgents (Awokoya, 2019; OCHA, 2019; Sunday, 2019; UNICEF, 2019; Idowu, 2016; Okeowo, 2015). That part, however, has been shielded from being seen by the media, either because of the male-dominated profession, as stated by different scholars (Oppenheim, 2019; Guaglione, 2019; Deutch, 2019; Ponsford, 2017; Women Media Center, 2017), or due to the limited access granted to journalists covering the crises, who can only report what they have been granted access to report by the military authorities (Rozen, 2019; Reporters Without Borders, 2016).

The findings are supported by the Feminist Muted Group Theory created by Edwin and Shirley Ardener in 1975, as stated in West & Turner (2018). Women were muted and presented as a marginalized group in reportage about military operations against Boko Haram. Their contributions were significantly downplayed and, in other instances, omitted entirely to reflect the views of the male gender. Women have also been relegated and denied power as can be seen from the newspaper bylines and sources in the stories analyzed. The male gender has used its relative advantage to propagate scenarios that are flattering to men, which do not reflect the true situations of things in the northeast of Nigeria. In fact, men have it worse compared to women when captured by either the military or Boko Haram, because they are either imprisoned or summarily executed. Women mainly serve as domestic servants, sexual tools and wives to Boko Haram members when captured, compared to males that are always bound and restricted when kept alive. These narratives, however, have been kept away from the media; instead, only the harsh treatment meted out to women is reported, while men are projected as saviors or oppressors but rarely as victims. This suggests a continuation of the paradigm of portraying the female gender through the lenses of male binoculars characterized by sexism and discrimination against women, who are usually referred to as the weaker sex. Moreover, this concept is reinforced by images of women being kidnapped (by men) and rescued (by men), with little or no emphasis on the strong attributes that can be used to identify women who are doing an immeasurable humanitarian work in the region providing support services for the military, the injured and vulnerable groups, as well as those on the frontlines as part of the military or journalists who, judging from the pictures tale of reportage about military operations against Boko Haram, do not exist. The only visible women in pictures are those being kidnapped or rescued; every other category of women have been rendered invisible, deleted, denied and obscured from press picture gallery.

Research question 2: What gender peculiarities were observed in the journalists covering news stories about military operations against Boko Haram?

The findings of this study indicated that bylines were used more often in reports about military operations against Boko Haram in other than Nigerian newspapers. The implication is that the newspapers have established correspondents that cover the beat under review as such, and sources have target journalists when they have information about military operations against Boko Haram insurgents that they consider relevant and want to share with the public or government. Regarding news stories without bylines, they were written by press agencies, with the most popular being News Agency of Nigeria, the national press agency in Nigeria. They were mostly used by Premium Times, while others used the name of the newspaper or left the byline section blank altogether, especially in Daily Trust, The Nation and Vanguard. Table 3 shows that the use of bylines among the selected newspapers was fairly similar regardless of the number of stories contributed by each newspaper for the study. Premium Times had the highest with 33 (31%) and Daily Trust had the least with 22 (21%) of news stories with bylines. From the byline, we were able to determine the gender of the journalist(s) for each story. Bylines help to raise the profile of the named journalists and could be useful when applying for fellowships and grants, as well as when trying to move up the job ladder in advertised positions in the same media organization or other media organizations.

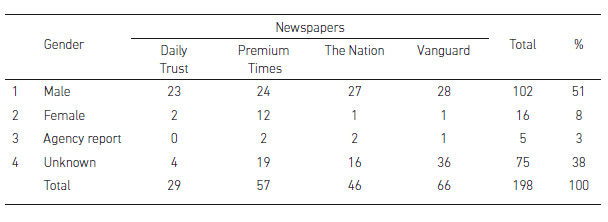

Table 4 presents the genders of the journalists as obtained from the bylines. Stories with male bylines outnumbered female’s by 102 (51%), followed by those unknown which totaled 75 (38%). Stories with female bylines accounted for 16 (8%). Premium Times had the most female bylines with 12 entries, while the other newspapers contributed one each. A further analysis of the findings revealed that Premium Times, The Nation, and Vanguard female reports were attributed to only one female reporter each, while Daily Trust had two female reporters. A closer look further revealed that nine of the twelve Premium Times reports were written in 2014, while the other three were written in 2015. Premium Times had no female reports in 2016, Daily Trust had one each in 2014 and 2016, The Nation filed one in 2014, and Vanguard had a solo female entry in 2016.

This takes us to the observations by Guaglione (2019), Deutch (2019), York (2017), and others that men have dominated journalism practice while women have dominated the classrooms. The underrepresentation of women in the journalism field is one of the reasons―as we saw earlier―why female images have less focus on the print. Moreover, the number of women journalists is expected to further decrease when the topic is about violence and conflict because of the higher risks of injury, physical and sexual assault, and in extreme cases death of the journalist. Nwabueze (2012) highlighted that the low number of female journalists in Nigeria may be due to the high premium requirements of the job rand that female reporters may find it cumbersome to combine the rigors of maintaining balance between work and family, coupled with work related bias and cultural factors that enthrone patriarchy in the society, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Research question 3: What is the gender disparity in the sources cited in news stories about military operations against Boko Haram?

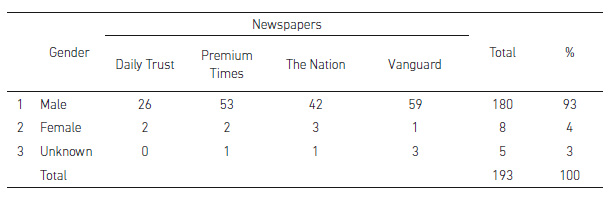

The sources mentioned in news stories about military campaigns against Boko Haram were classified by gender and presented in table 5. Findings revealed a total of 193 sources in 185 news stories. Male sources outnumbered female’s and were found in 180 (93%) of the 193 sources identified in the stories analyzed, compared to female sources which totaled eight (4%). All the newspapers used over 90% male sources for all of the stories analyzed individually. This continues highlighting the trend of male dominance discussed by Deutch (2019), who analyzed the issue around journalism, which has remained dominated by male reporters and their male sources. This means that issues would be seen from males’ perspectives, underrepresenting the views of the opposite gender and creating a gender imbalance in reportage and, by implication, gender bias.

We can relate this situation with the pictures presented before, where all of them showed women being rescued, running away from or being widowed by Boko Haram’s violence. Hines (2008), when discussing the Radical Feminist Theory, states that this also keeps perpetuating male dominance: the observed bias consists of male journalists seeking information from fellow male sources even though there are as much or more females in the area at the time of occurrence of the event. Amobi (2013), when explaining the Feminist Muted Group Theory and how women are excluded in media discussions, suggested that in every society a social hierarchy exists, whereby certain privileges are granted to one group and not the other. In this sense, the group with the advantage determines to a large extent the communication system for that society, and the muteness occurs due to lack of power accorded to the group at the lower rung of the ladder. Among the sources seen in this study, journalists rarely speak to the female locals as sources. Efforts should be doubled to include female sources in such news reports. This would be more likely to happen if more female journalists were added to the pool covering military operations against the Boko Haram group.

The lack of power accorded to women in the newsroom means that their views are muted and presented through the lenses of the supposed ‘superior gender,’ as we saw earlier in the presentation of women as people being kidnapped by the Boko Haram group (mostly men) and rescued by the soldiers (another group of men). Thereby, women’s lives in the northeast of Nigeria seem to be in the hands of men, one group for the worst, another group for the best, and the news reports have tacitly negated the role of women in fighting the insurgency as they have not been in such role in the pictures or bylines of journalists reporting about the conflict, or providing information to the press about military operations in the region.

Despite the fact that there were many stories where women were rescued by Nigerian soldiers from Boko Haram captivity, yet there were no mention of interviewing any of such women about their experiences during captivity and their rescue, or how they have been cared for since their freedom from the Boko Haram insurgents. The insight the women would provide will give the government and the public a firsthand look at the behind-the-scene operations of the terrorist group. The stories of these women would also warn other women and the public in general about the modus operandi of the group, how to avoid being captured, and the early warning signs that signal danger of an impending attack. The voices of these women would be immense, and this calls for many questions as to why the media does not bother to include the voices of such women in their stories.

Women’s voices should be heard especially in today’s #MeToo Movement, where women are creating media awareness about the treatment of women in a world dominated by men. This made the Bring Back Our Girls advocacy group (dedicated to the return of the kidnapped Chibok girls) to question the military in one of their claims of rescuing 1,000 people (mainly women and children) kidnapped by the insurgents (Ukpong, 2018). The group questioned the authenticity of these rescues and requested a publication of images of the rescued people in both print and electronic media. Hearing the account of these rescued women will give credence to information put out by the military; in fact, the stories of these rescued women deserve to be heard.

Research question 4: How are the women portrayed media in reports about military operations against Boko Haram?

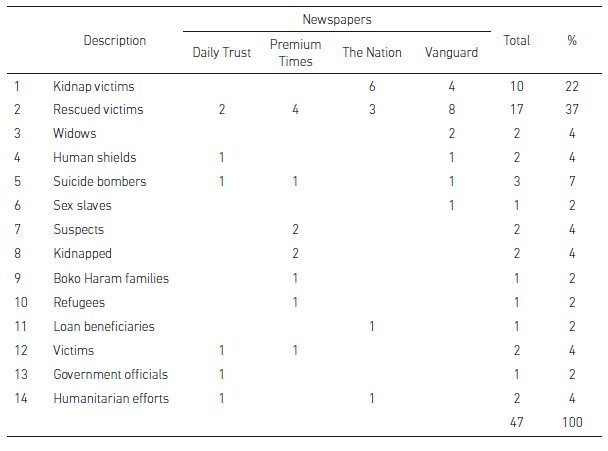

Question 4 addresses how women were portrayed in news reports about military operations against Boko Haram in the northeast of Nigeria. The significant finding shows that 59% of the women were portrayed as being kidnap victims or rescued victims from Boko Haram insurgents compared to 6% regarded as government officials or humanitarian efforts in bringing an end to the conflict. Thus, the reports present women as vulnerable and weak, who need to be protected from the horrors of the war. However, we have seen from literature that women have been involved in fighting against the insurgents and reporting about the conflict (Sunday, 2019; Idowu, 2016; Okeowo, 2015), and providing humanitarian services (Awokoya, 2019; UNICEF, 2019). Other portrayals deducible from the data present women as widows (of soldiers, Boko Haram fighters and residents in the conflict zone), human shields for Boko Haram, suicide bombers, sex slaves to Boko Haram fighters, suspected Boko Haram members, victims of kidnapping by the insurgents, or family members of Boko Haram fighters.

From the underrepresentation and misrepresentation of women observed in the images used in the reports, all the bylines and sources included in news reports lead to the portrayal of women to suit the narrative of the storytelling gender, who will present events from their own lenses. As mentioned before, Fab-Ukozor (2004) points out that media reports are unbalanced against women, with little reporting about their issues except when they are presented as models in ads. And, as the reports under study are about violence and have nothing to do with beauty or skincare, the viewpoint would be to present the female gender as a little child to protect from the horrors of war, thereby downplaying its contributions in support of the government and in bringing an end to the conflict. The main reason for the negative portrayal of women is that control of media is either by the government and media owners who are mostly men and, as such, would not be bothered about issues beyond their sphere. The portrayal of women will positively improve with more women getting involved in the reporting and also including more female sources in the reporting. In this regard, the enabling environment has to be put in place to encourage the participation of more women not only in reporting about the Boko Haram violence but also journalism in general, in order to advance women issues and put them in the spotlight positively.

Research question 5: Are there incidents involving violence (arrest, kidnapping, sexual assault, physical assault, online hate speech) against female journalists covering military operations against Boko Haram?

The findings for research question 5 did not produce any results as there were no reports of violence against any female journalist covering military operations against Boko Haram insurgents. This is because of the low number of women seen in the bylines of news reports. There were five women in total seen from the 185 news reports used for the study, with Daily Trust having two female journalists and the others one apiece. The low participation of Nigerian women in journalism is captured in the World Economic Forum (WEF)’s Global Gender Gap Report 2020, where Nigeria ranked 128th out of 153 countries (WEF Report, 2020). An improvement to get Nigeria into the first 100 nations should be the next benchmark. Further improvements are to be expected with reforms and laws that promote equality in the workplace and empowerment for women that will enable them to compete on the professional level with men.

Conclusion

There is a need for gender diversification in both the journalists covering military operations against the Boko Haram group and the sources cited in their news stories. Women have been contributing immensely to the war efforts as soldiers and aid workers in the northeast of Nigeria: some have been targets of Boko Haram attacks, and many of them have been rescued by the military in many operations as reported by the media. It is however inadequate that none of these many women have been interviewed about their rescue when reporting about military operations. Was this exclusion deliberate or by accident? This could be a bias by journalists who are mainly male choosing not to interview women, or a lack of access to the rescued women. Either of which, the journalists have not mentioned impediments in their attempts to hear about the experiences of these rescued women. The experiences that would be recounted by these women would extoll the heroics of the military that rescued them, as well as give hope to relatives of yet-to-be-rescued women that the military will one day rescue from captivity.

The study recommends that the number of female journalists covering beats on Boko Haram, especially with regard to military operations, should be increased. Diversity is currently a global theme and can improve the journalism profession. Due to the dynamic nature of the job, there are certain areas where a female journalist will find it easier to get information, and such a blend of both genders will make a better team. In this vain, journalists should diversify their sources for news stories about military operations by including more females. This will ensure that different points of view are presented to enable a better perception of the issues under discourse and allow the government to come up with a holistic plan that addresses problems as they arise.