INTRODUCTION

Financial inclusion has become an essential tool for the sake of progress of households, businesses, and economies all around the world. Its influence in economic development, reduction of inequality, trust building, increased productivity and people empowerment are object of study.

In Peru, financial inclusion is a relevant matter continually monitored by numerous public and private entities, involving people’s capacity to access financial services such as bank accounts, bank loans, insurance, among others. In this regard, various measures have been taken to improve financial inclusion in Peru.

According to Castillo (2018), financial inclusion has a significant impact on people’s daily lives, where “financial entities provide a service on commission, through credit or placement; the commission (interest rate) being obtained through a deposit. Although this generates a deposit interest rate to the entity, currency gets into circulation through other placements” (p. 8).

Also, Vargas Garcia (2021a) defines financial inclusion as a multidimensional concept encompassing the supply and demand of financial products or services, where the objective is to improve “access, usage, quality and impact on the financial wellness of families and businesses” (p. 110). The author emphasizes that financial inclusion entails providing people and businesses with access to various beneficial financial products. Moreover, Córdova Galarreta shares the belief that the process implies safe, adequate, and efficient access to diverse financial services. The goal is a responsible financial market with broad population participation at minimal costs.

Furthermore, Orazi et al. (2021) discuss that financial inclusion seeks to provide access to formal financial services, enabling people and business “to make payments, save, obtain insurance or credit, and invest in education, housing or business ventures” (p. 64). As a result, economic development is fostered, and the gap in poverty reduction is narrowed.

In addition, the statements of the Superintendencia de Banca, Seguros y Administradoras Privadas de Fondos de Pensiones (SBS) [Superintendency of Banking, Insurance and Pension Fund Administration in Peru] must be highlighted since they indicate that financial inclusion contributes to the development of a trustworthy and long-lasting financial system. This is achieved by fostering the participation of communities in the financial system, enabling them to use banking products throughout their lives, and seeking the reduction of informality. Moreover, the Superintendency works as a facilitator of “a responsible financial inclusion process, aiming to strike a balance among inclusion, stability, trustworthiness, and financial protection” (Superintendencia de Banca, Seguros y Administradoras Privadas de Fondos de Pensiones, 2023, par. 2).

On the other side, the lack of financial inclusion had long been a problem for people in Latin America and the Caribbean. However, this situation has gradually changed over the years, and now users have more opportunities to access products and services that cater to their needs (Orazi et al., 2019) .

Despite the various benefits offered by financial entities in Latin America and the Caribbean, only 39% of people seek loans due to limited knowledge about or access to the financial market. Additionally, approximately 50% of adults worldwide have just one account in a financial institution, leading others to rely on informal mechanisms to meet their needs. The low demand for financial services arises from the lack of financial education and the relatively low income levels of people globally, preventing them from fully utilizing and benefiting from economic access through a financial entity (Pérez & Titelman, 2018).

From a post pandemic (COVID-19) perspective, the topic of digital financial inclusion is receiving extensive attention and is now recognized as a crucial development and resilience tool. Some authors even consider digital financial inclusion “as an element contributing to the reconstruction and strengthening of the economic flow and financial system; actions for its adequate adoption are being proposed” (Cardona Valencia, 2020, p. 183).

Financial inclusion has recently become an indispensable tool for the development and progress of households, businesses, and economies in various countries around the world, representing stability, economic growth, and reduction of inequality. Financial entities, in turn, aim to generate products and services that help mitigate informality and narrow the previously mentioned gap. Furthermore, financial inclusion is understood as a means or mechanism to provide access and usage within the financial system by certain population. These individuals require quality products that satisfy their needs and contribute to their personal and social development, with the expectation of maintaining stability over time.

The issue of financial inclusion in Peru is closely linked to the development of microfinance. There is significant concern to promote the growth of this emerging market, with various financial entities participating in this endeavor (Toledo & León, 2021).

The purpose of this research is to analyze the evolution of financial inclusion in Peru over the past seven years (2016-2022). This analysis considers indicators established by NFIS (National Financial Inclusion Strategies) and reports from the SBS. The results highlight identified issues and provide insight into the necessary steps to include the greatest number of Peruvian population possible, in view of the essential nature of financial inclusion for the progress of households, businesses, and economies.

SCOPE OF THE REVIEW

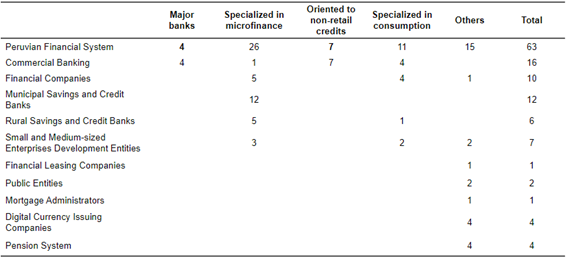

As shown in Table 1, according to the Superintendency of Banking and Insurance, there are different financial service providers operating in Peru (63 regulated institutions in total).

Table 1 Financial service providers by June 30, 2022

Note. Prepared with data taken from Perú: Reporte de Indicadores de Inclusión Financiera de los Sistemas Financieros, de Seguros y de Pensiones. Diciembre 2022, by Superintendencia de Banca, Seguros y Administradoras Privadas de Fondos de Pensiones, 2022 (https://www.sbs.gob.pe/inclusion-financiera/cifras/indicadores).

The table displays the regulated financial products and services offered. Notably, the participation of entities specialized in microfinance stand out, as they hold more than 50% of the credit portfolio for small and medium-sized enterprises. It is worth mentioning that microfinancial entities in Peru contribute significantly to financial intermediation in Latin America and globally (Toledo & León, 2022, p. 137). Other participants in the market include entities focused on non-retail credits, those specialized in consumer loans, and public institutions such as Agrobanco and Banco de la Nación. It is important to highlight that private banking plays a crucial role in the financial inclusion process for small and medium-sized enterprises in Peru, under the supervision of the SBS (León, 2017).

As a general overview, the World Bank considers that registering a financial account is the first step toward greater and better financial inclusion. Having a financial account enables people to conduct various transactions such as collections, payments, and money transfers. The ultimate aim is to ensure that a significant number of people worldwide have access to essential financial services. Financial inclusion is defined as “the access people and businesses have to different useful and affordable financial products and services that satisfy their needs -transactions, payments, savings, credit, and insurance- and that are provided in a responsible and sustainable manner” (Banco Mundial, 2022, par. 1).

In addition, financial inclusion is closely linked to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (Global Goals), which is why the “World Bank considers financial inclusion as a key facilitator in the reduction of extreme poverty and promotion of shared prosperity” (Banco Mundial, 2022, par. 4).

According to Gonzáles-Sierra et al. (2023) there is a direct, intense and significant relation between financial inclusion and economic complexity, as evidenced by their study conducted in Mexico. Furthermore, Lemus y Rojas (2022) highlight the crucial role played by cooperatives in promoting financial inclusion, especially for low-income individuals, retirees, women, and residents of small rural towns in Chile. These findings underscore the global importance of financial inclusion, particularly in the context of financial institutions’ involvement.

Financial inclusion is emerging as a new paradigm of economic growth that plays a major role in alleviating poverty from the country. It refers to delivery of banking services to masses, including both privileged and disadvantaged people, on affordable terms and conditions. Financial inclusion is a significant priority for the country’s economy growth and societal advancement, as it helps reduce the gap between the rich and poor populations (Iqbal & Sami, 2017).

The enabling environments for financial inclusion in the world, especially in Latin America, are favorable. Colombia and Peru stand out as countries with the best environments and the most favorable indicators for the development of financial inclusion. In the 2019 Global Microscope, Peru ranked second. Compared to the scores in the previous Microscope edition, Peru showed an improvement in Consumer Protection, thanks to its data protection framework for financial customers, which is implemented by a specialized agency in the Ministry of Justice (The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited, 2019).

The active participation of both the public and private sectors is essential to achieve financial inclusion in Peru. They must work collaboratively and cooperatively, providing mutual feedback to promote financial inclusion through shared actions that contribute to the decentralized and inclusive economic development while preserving financial stability. Since August 2015, Peru has implemented a national strategy to increase financial inclusion, with the government aiming to ensure that at least 75% of adult population will have registered and have access to a bank account for all financial transactions in the coming years (Banco Mundial, 2015).

In Peru, the regulatory framework for financial inclusion is guided by the Comisión Multisectoral de Inclusión Financiera [Multisectoral Committee for Financial Inclusion] (CMIF), a coordination and concertation entity with public and private participation -created in February 2014- in charge of monitoring and implementing the Estrategia Nacional de Inclusión Financiera [National Financial Inclusion Policy]. The Committee includes participants from the Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas [Ministry of Economy and Finance], the Ministry of Development and Social Inclusion [Ministry of Development and Social Inclusion], the Ministerio de Educación [Ministry of Education], the SBS, Banco de la Nación (Bank of the Nation), among other entities of the public sector.

The CMIF designed the National Financial Inclusion Strategy (ENIF) with the goal of promoting access “to and responsible use of integral financial services, which are reliable, efficient, innovative and meet the needs of different segments of the population” (Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas, 2015, p. 3). This strategy is structured under three pillars: Access, Use, and Quality/financial wellness. It encompasses seven lines of action, including payments, insurance, savings, funding, financial education, consumer protection, and support for vulnerable groups.

Subsequently, in 2019, the Política Nacional de Inclusión Financiera [National Financial Inclusion Policy] (PNIF) was approved to address the issue of low financial inclusion in Peru, focusing on the dimensions of access, use and quality. In this sense, the PNIF will be implemented through five priority objectives and sixteen policy guidelines. Figure 1 illustrates the three financial inclusion dimensions that addressed through policy instruments.

Note. Prepared with data taken from Estrategia Nacional de Inclusión Financiera, by Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas, 2015 (https://www.mef.gob.pe/contenidos/archivos-descarga/ENIF.pdf).

Figure 1 Financial inclusion dimensions

Access to funding

Access is a crucial dimension of financial inclusion, focusing on providing financial entities’ presence in the most vulnerable segments. To achieve this goal, decentralized customer service spots will be implemented in proximity to these segments. Silva (2022) defines access as “putting in-person customer service spots at the population’s disposal, estimating territory coverage, meeting unsatisfied or vulnerable demands through the provision of various services, and maintaining their quality” (p. 14).

The financial inclusion strategy establishes that “the expansion of the geographic coverage of financial services will contribute to the goal of enhancing access to financial services for the population, promoting greater financial inclusion in the country” (Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas, 2015, p. 41). One of the significant issues identified is the concentration of distribution channels within urban areas, with limited or no distribution channels available in rural areas.

As part of the established strategy and in order to increase the reach of financial services, the following requirements must be met:

Keep up with the promotion and expansion of customer service spots (offices, ATM, banking agents) especially in areas with no presence of financial system; get greater inter-operability among such customer service spots; reduce infrastructure gaps; develop alternative distribution channels, mainly digital ones that make financial inclusion easier; and use the existing public and private programs to include populations or regions currently excluded from the formal financial system. (Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas, 2015, p. 41)

Vera-Colina et al. (2014) state that access “involves the possibility that an economic agent has to obtain resources for any activity of its interest, such as a debt or having assets approved in due time” (p. 153). From an entrepreneur’s standpoint, Gómez et al. (2022) “proposes that entrepreneurs should have access to capital regardless of possible restrictions, which represents a reduction in income inequality”. As a result, institutions offer different financial products to provide funding for entrepreneurs, enabling them to increase capital, acquire assets for their enterprises, or even improve their homes. This is the reason why the promotion of the use of financial products leads to the improvement of the level and quality of life of small and medium-sized entrepreneurs (Toledo et al., 2022).

Financial system’s customer service infrastructure is a crucial “access to financial services” indicator, where the broadening range of services reflects decentralization, cost reduction, and growing transaction numbers through the substitution of some in-person operations (Zamalloa et al., 2016). That is to say, indicators of the “Customer service infrastructure” include infrastructure of offices, Automated Teller Machines (ATMs), banking agents, basic operations establishments, service spots (per 100 thousand inhabitants), and customer service channels (per 1000 km2).

Another indicator to help assess “access to financial services” is the “availability of the financial system service network”. To gauge this, the number of offices, ATMs, banking agents, and customer service establishments and spots are considered. In this sense, Córdova Galarreta (2021) mentions that the initial stride towards financial inclusion involved introducing baking agents, which enabled banking companies, financial companies, and non-bank entities to function through these agents. This allowed for easy consultation and payment transactions without the necessity of visiting a physical bank. As a result, financial inclusion saw a boost, agency costs were minimized for financial users, and credit access was enhanced for previously underserved population segments.

Therefore, access refers to the opportunity citizens have to utilize financial services offered by banking entities, which is measured through different variables, including customer service infrastructure and the availability of the Peruvian financial system. This infrastructure encompasses offices, branches, ATMs, banking agents, as well as establishments with POS systems, such as grocery stores, drugstores, and shops. It is worth mentioning that digitalization of products and services through mobile banking on cell phones and internet banking on computers, serves as a highly useful and efficient tool, facilitating a wide array of services. For instance, it enables the immediate payment of public services and allows elderly individuals to open bank accounts without the need to visit an agency in person. Moreover, this digital transformation benefits financial institutions by reducing the implementation costs of offline channels.

Use of financial services

Another dimension of financial inclusion is the “Use of financial services,” which pertains to the number of debtors utilizing financial services in Peru. This metric reflects the population’s demand for and use of these products, directly related to their financial capacity and consumer protection.

To clarify, “use” refers to the demand from the population that has access to financial products and services (Vargas Garcia, 2021b). This trend is advantageous as it enables the population to save surplus capital from their work, lift themselves out of poverty, and prepare for future investments and contingencies.

The goal of financial inclusion in Peru is to promote the increased use of financial products and services available in both the banking and non-bank sectors. It is stated that the main focus is to strengthen and stabilize the financial system by creating a diverse ecosystem of complementary financial products and services. This approach aims to meet the timely needs of the population, tailored to the specific characteristics of different segments (Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas, 2015).

Therefore, the purpose is to improve the financial information available to the population in order to strengthen the preferences of potential debtors, enabling them to access to a broader range of financial services and increasing demand. This will empower them to save, make payments, remit funds, make deposits, and meet their financial needs in a short and medium term.

Another matter that must be addressed is the skepticism among a part of the population towards financial system entities due to negative experiences they have encountered. As a result, the Peruvian Government’s objective is to promote financial skills - “financial education” - throughout various life stages, equipping individuals with tools to create integral strategies and address different financial circumstances (Superintendencia de Banca, Seguros y Administradoras Privadas de Fondos de Pensiones, 2023).

An obstacle to inclusive development is the fact that a significant portion of Peruvians, representing 47% in 2018, 43% in 2019 and 39% in 2020, are marginalized from internet usage due to lack of access, which hinders bank digitalization and interoperability (Vargas Garcia, 2021a).

For the purposes of this research, the indicators for the variable “use of financial services” will include the number of debtors, deposit accounts (both in thousands), and card holders (adult population). Given the increase in usage, more households, businesses, and undertakings will be able to access a wider range of financial products, leading to higher demand and fostering more inclusive economic growth.

Quality/wellness of financial services

Quality in financial services is key when acquiring a product, as having alternative channels accelerates and minimizes waiting times while simplifying service processes. According to Morillo (2011), globalization has intensified competition among financial institutions, driving them to invest in technology and innovation as means to secure customer loyalty; however, this environment also poses challenges and structural changes. The sheer volume of competitors makes it demanding to create truly distinctive products or services, leading to a situation where technological differentiation and innovations are swiftly adopted and enhanced by the competition (p. 103).

Quality and wellness are integral important components of financial inclusion because they are directly related to people’s and communities’ ability to access financial services that can fulfill their needs and help improve their economic and social situation.

In addition, the consumer financial protection office defines “financial wellness as the condition in which a person can fully satisfy their current and ongoing financial obligations, can be confident about their financial future, and is able to make decisions that let them enjoy life” (Carballo, 2020, p. 266).

According to the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau (CFPB) (2015), financial wellness refers to the ability to manage daily finances, cope with financial impacts, track and achieve financial objectives, and attain financial freedom based on personal knowledge and characteristics. Moreover, financial health, another term used synonymously with financial wellness, encompasses the effectiveness of financial systems in assisting individuals in handling unforeseen events that could impact their finances and creating opportunities to attain their goals (Uribe & Urquijo, 2022, p. 4).

So, it can be said that “quality” refers to the offering of financial products and services that are reliable, transparent, accessible, and suitable to people’s needs. Therefore, institutions must provide clear information about their products in an easily understandable manner. In turn, wellness refers to the benefits people obtain from financial services, like the capacity to save, invest, access to credit, and protect themselves against financial risks within the system. It is expected that the government has the capacity to optimize its resources to achieve positive results in the short and long term. This will enable financial services to be accessible, useful, and beneficial to the entire population, especially targeting vulnerable individuals or those who have faced financial exclusion.

Access to financial services

Availability of service network

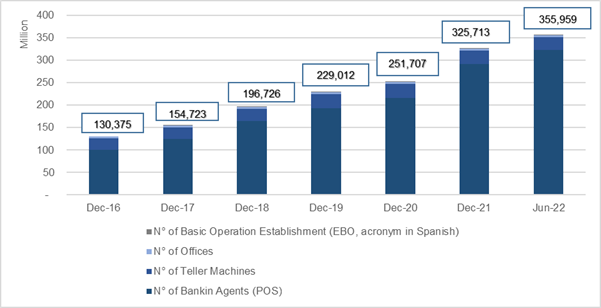

The availability of the customer service network within the financial system has experienced significant growth since December 2016. As of June 2022, there are now over 355 thousand access points, representing a remarkable increase compared to the modest figure of just over 130 thousand points in December 2016 (a growth of 173%) (See Figure 2).

Note. Prepared with data taken from Perú: Reporte de Indicadores de Inclusión Financiera de los Sistemas Financieros, de Seguros y de Pensiones. Diciembre 2022, by Superintendencia de Banca, Seguros y Administradoras Privadas de Fondos de Pensiones, 2022 (https://www.sbs.gob.pe/inclusion-financiera/cifras/indicadores).

Figure 2 Evolution of service network availability

This increase in the service network availability is explained by the growing number of banking agents. Also, a change in the components of the customer service network is observed: An increase in the number of banking agents (90.6% in June 2022 compared to 77.3% in December 2016) and a reduction of the number of teller machines and offices (8.2% in June 2022 compared to 19.1% in December 2016, and 1.2% in June 2021 compared to 3.5% in December 2016, respectively) (See Table 2).

Table 2 Components of the customer service network

| Custumer Service Network | Dec-16 | Dec-17 | Dec-18 | Dec-19 | Dec-20 | Dec-21 | Jun-22 |

| N° of Offices | 3.5% | 3.0% | 2.4% | 2.1% | 1.8% | 1.3% | 1.2% |

| N° of Teller Machines | 19.1% | 16.1% | 13.6% | 13.4% | 12.3% | 9.0% | 8.2% |

| N° of Bankin agents (POS) | 77.3% | 80.8% | 84.0% | 84.4% | 85.9% | 89.6% | 90.6% |

| N° of Basic Operation Establishment (EOB) | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Note. Prepared with data taken from Perú: Reporte de Indicadores de Inclusión Financiera de los Sistemas Financieros, de Seguros y de Pensiones. Diciembre 2022, by Superintendencia de Banca, Seguros y Administradoras Privadas de Fondos de Pensiones, 2022 (https://www.sbs.gob.pe/inclusion-financiera/cifras/indicadores).

This positive factor reflects the ongoing improvement of infrastructure to cater to potential users, considering the opportunities for financial inclusion in areas where the expansion and improvement of microfinance networks or associations are necessary (Álvarez, 2013).

López-Sánchez y Urquia-Grande (2023) highlight the significant challenge of high costs in achieving financial inclusion for the population. However, there are programs willing to lower such costs, especially for the rural population, by providing access to mobile devices through partnerships with strategic allies like COPEME, EQUIFAX.

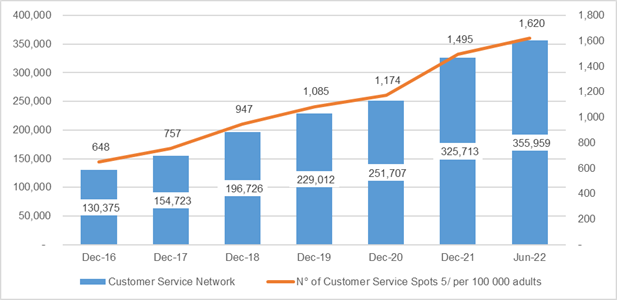

In June 2022, there were 1620 customer service spots per 100 thousand adults, which is 150% higher to the figures observed in December 2016 (648 customer service spots per 100 thousand people). By June 2022, 25 customer service channels per 100 km2 were reported compared to 90 customer service channels reported in December 2016 (See Figure 3).

Note. Prepared with data taken from Perú: Reporte de Indicadores de Inclusión Financiera de los Sistemas Financieros, de Seguros y de Pensiones. Diciembre 2022, by Superintendencia de Banca, Seguros y Administradoras Privadas de Fondos de Pensiones, 2022 (https://www.sbs.gob.pe/inclusion-financiera/cifras/indicadores).

Figure 3 Evolution of customer service network availability and number of customer service spots per 100 thousand people

Customer service infrastructure

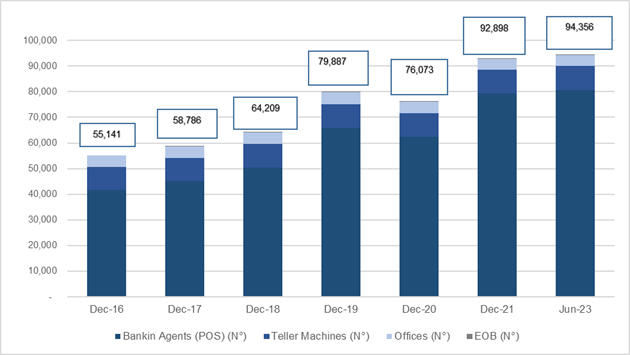

By December 2016, the customer service infrastructure in the financial system represented 55,141, which increased by 71% to reach 94,356 by June 2022. This improvement in customer service infrastructure was primarily driven by a 94% growth in the number of banking agents (See Figure 4).

The trend of the growing number of customer service network availability and the increase in the number of customer service infrastructure is a result of the expansion of banking agents. It was also evidenced that the number and participation of offices have decreased. The cost difference between opening an office and establishing banking agents supports the strategy of access to financial services.

Note. Prepared with data taken from Perú: Reporte de Indicadores de Inclusión Financiera de los Sistemas Financieros, de Seguros y de Pensiones. Diciembre 2022, by Superintendencia de Banca, Seguros y Administradoras Privadas de Fondos de Pensiones, 2022 (https://www.sbs.gob.pe/inclusion-financiera/cifras/indicadores).

Figure 4 Evolution of customer service infrastructure

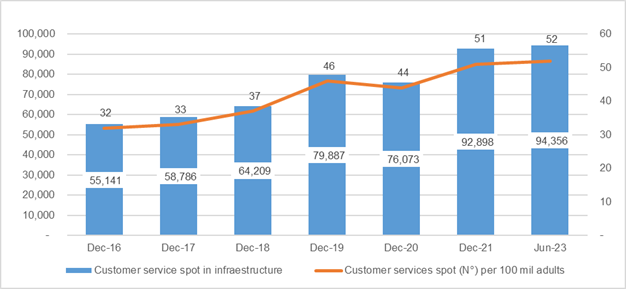

In June 2022, the number of customer service spots infrastructure was 430 per 100 thousand adults, which is 57% higher than the figure reported in December 2016 (where the number of customer service spots in the infrastructure was 274 per 100 thousand people). Regarding customer service channels, by June 2022, the number of customer service channels infrastructure was 52 per 100 Km2, compared to 32 reported in December 2016 (See Figure 5).

Note. Prepared with data taken from Perú: Reporte de Indicadores de Inclusión Financiera de los Sistemas Financieros, de Seguros y de Pensiones. Diciembre 2022, by Superintendencia de Banca, Seguros y Administradoras Privadas de Fondos de Pensiones, 2022 (https://www.sbs.gob.pe/inclusion-financiera/cifras/indicadores).

Figure 5 Evolution of customer service infrastructure and customer service spots infrastructure (number) per 100 thousand people

There has been an increase in the number of customer service points and the infrastructure of customer service points per 100 thousand adults, indicating a significant expansion in the availability of financial services. This growth stands in contrast to the information provided by the Global Findex 2021 financial inclusion report (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2022), which indicates that in Peru, 56% of people surveyed now report having an account in a regulated organization, compared to only 20% a decade ago. This evidence demonstrates the growing access to financial products.

Use of financial services

Although Global Findex 2021 financial inclusion report on Peru shows a 36% progress in a decade in terms of access to a transaction account, the same indicator evidences a delay compared to global figures (76%) and those for Latin America and the Caribbean (74%) (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2022).

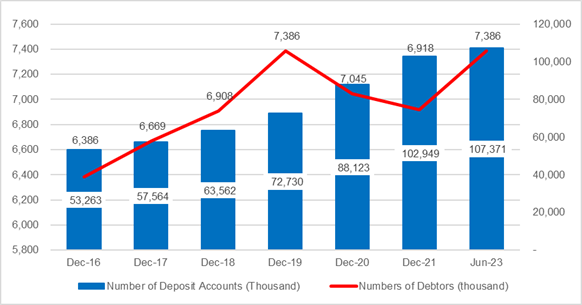

On the same topic, the SBS financial inclusion report (Superintendencia de Banca, Seguros y Administradoras Privadas de Fondos de Pensiones, 2023) shows a sustainable growth in the number of deposit accounts. In June 2021, there were more than 107 million accounts, compared to 53 million reported in 2011. Nonetheless, the debtor number indicator amounts to 7.4 million for June 2022, compared to 6.4 million in 2011, showing a lower growth. It should be noted that that COVID-19 pandemic provoked a reduction in this indicator, and it has been recovering to its pre-pandemic level only since 2021 (See Figure 6).

Note. Prepared with data taken from Perú: Reporte de Indicadores de Inclusión Financiera de los Sistemas Financieros, de Seguros y de Pensiones. Diciembre 2022, by Superintendencia de Banca, Seguros y Administradoras Privadas de Fondos de Pensiones, 2022 (https://www.sbs.gob.pe/inclusion-financiera/cifras/indicadores).

Figure 6 Evolution of number of deposit accounts (thousand) and number of debtors (thousand)

CONCLUSIONS

As a result of this research, it can be observed that Peru made meaningful progress in financial inclusion over the past years. However, there are still major challenges that need to be addressed; for example, the indicator of 56% of customer service of Peruvian adults holding a bank account (31% of adults in rural areas and 64% in urban areas) falls short of the government’s goal of 75% proposed in the National Financial Inclusion Policy in Peru. This goal was established to ensure greater financial access for all citizens.

The disadvantages observed in the appraisal include the high costs of expanding financial service infrastructure (which prevents more access), limited or poor financial education (limitation for more use), more developed growth in urban areas than in rural areas (people in rural areas often have more difficulty in accessing financial services due to inadequate infrastructure and a lack of knowledge about financial services), and poor understanding of customers’ needs. This conclusion aligns with the findings of the investigation conducted by Zamalloa et al. (2016), as mentioned in the background of this research.

On a positive note, technology has played a significant role in promoting financial inclusion in Peru. The increased use of mobile phones and internet has enabled the presence of financial services in remote areas, extending access to people who had never had it before (Banco Central de Reserva del Perú, 2022). The rise in the number of banking agents and non-bank agents has also been crucial to this growth.

It is essential to highlight that there is still a long way to go as a country to implement more effective public policies that promote the development of financial inclusion, requiring support from the private sector.

Regarding the regulatory framework, the government should include on its agenda the implementation of laws that create facilitating conditions to microfinance institutions and small enterprises. Moreover, there is a need to improve decentralized financial education and enhance cybersecurity measures to protect digital transactions. Strengthening mechanisms to foster collaboration between public and private companies would also benefit microfinance entities and small enterprises. As a future research direction, studying the effects of the PNIF on the level of financial inclusion in Peru would be advantageous.