1. Introduction

Online commenting is probably one of the most common features brought by the digitization of journalism. This interactive concept fits perfectly into the twenty-first century framework, as media institutions constantly try to understand how audiences read, respond, curate and manage content (Gallagher et al., 2019). Imperative as it is for web metrics and the business plans with advertise ment companies, audiences are lured into all sorts of attention policies, ranging from appellative headlines, clickbait strategies and comment. Dealing with comments, for instance, remains as an intriguing dimension of the so-called “participative culture”, following Henry Jenkins’ (2015) fa mous definition.

Friend and Singer (2007) suggest that online media should be accountable for an interactive en vironment, as long as ethical guidelines are disseminated and respected amongst users. Domingo (2014) proposes a similar idea, thus encouraging journalists to take responsibility on the technical tools to allow audiences comments. Bruns (2014) states that these ethical questions have been par ticularly fostered by commercial standards, since commenting has been a common feature in the media in the last decade.

From an ethical perspective to a technical one, it could be argued that online users read the news through news aggregators, news publishers’ websites and social network sites. Access is easily pro vided by desktop, laptop and mobile devices. This engagement with the online content includes a whole range of activities in the reading scope, such as sharing news articles, save articles, posting comments (Lee & Ryu, 2019). A Pew Research Center report, on September 2019, estimated that “the share of Americans who prefer to get their news online is growing” and concluded that the preferences are no longer concentrated in the classic media. The Digital News Report 2019 also stressed out differences in the relationship between producers and readers: “across all our countries, just 29% now say they prefer to access a website or app directly - down 3 percentage points on a year ago. Over half of our combined sample (55%) prefer to access news through search engines, social media, or news aggregators” (2019: 13).

Online commenting can be understood as a strategy of interaction. In doing so, Mark Deuze (2001) defined three types of interactivity: navigational (‘Next Page’ and ‘Back to Top’ buttons or scrolling menu bars); functional (direct mailto, links and moderated discussion lists); and adaptive (cha trooms and personal customization of websites). Boczkowski (2004) adds a fourth perspective: the contact interactivity, as it allows users to contact instantly with the owners of a webpage. Online news commenting stands in this last framework.

Kangaspunta (2018) defined research on online news comments as dominated by two typical approa ches: a normative one, dealing with the examination of media policies towards comment spaces; and the other one centred on media engagement. This research is inspired by the first framework, thus exploring communication policies towards online commenting. It is also safe to admit that media professionals share multiple levels of concerns regarding this interactive possibility. If we assume that online comments add “richness and complexity of thought to the platitude “consider your audience” by developing complicated understandings of textual production and distribution processes” (Galla gher, 2018: 35), it is relevant to contribute with insights about how to handle with this digital public sphere. As far this research concerns, it is intend to map, present and discuss current practices to open/ close these digital doors to let audiences interact with media and amongst individuals.

2. Wide-ranging policies in online news comments

Although it is argued that online spaces to comment are relatively well known by the general grasp of audiences, it is also wise to consider that media productions are still sharing doubts about the most suitable models to handle with online comments. Managing the multilanguage and multi-formats aspects of digital communication is a paramount challenge for media organizations (Palau-Sampio & Sánchez-García, 2020). Tanjev Schultz (2006) concluded that media outlets do not necessarily explore the challenge of interactivity in the most effective way; they tend to provide only token interactive options.

Yet relatively common in websites, some of the biggest players in the media market have already opted to remove comment sections in their online news articles (Liu & McLeod, 2019). However, expert in social media management Tamara Littleton (2011) explained four options of how journa lists can best deal with comments2:

pre-moderation: although it consumes a lot of time to process and analyse all comments, it is the safest option, Tamara states. It guarantees that contributors respects the basic lines of a discussion;

post-moderation: letting all comments go live, but forcing them to be removed if abuses are found;

a combination of pre and post moderation: this was Reuters’s policy until very recently, as this news media “approved” commentators, “people who have a strong record of beha ving well in a community and having their comments approved - who can move away from pre-moderation to post-moderation”;

relying moderation to the community, asking users to flag and value comments among them - “this is an extremely grey legal area. In the main, brands take their duty of care very seriously, and agree that it is important to moderate thoroughly, to protect the brand’s own reputation and, of course, its users”, Littleton concluded.

Robert Niles (2010), a contributor of the Online Journalism Review, suggested that “If you can’t manage comments well, don’t offer comments at all”3. Niles regretted that media organizations did not have the ability to fight back troll farms, hence implementing an effective policy to tac kle with online commenting. Niles considered this disappointing, because readers should have the possibility “to discuss, extend or even correct those news articles”. Concerned with the existent non-moderation policies, the Portuguese Authority for the Media Regulation (ERC) has very re cently reminded that solid efforts shall be implemented “to moderate comment section in the online news (…) preventing the publication of insults, offenses and messages related to hate and discrimi natory speech”. In March 2017, Portuguese weekly newspaper Expresso removed comments from all online sections4. Later on, Expresso columnist Daniel Oliveira mentioned: “only a small group of readers did, in fact, noticed this change, which says a lot about what commenting means today”. In a very critical assessment about what he defined as “the garbage of internet”, Oliveira said that media producers should be accountable for the online comments, urging them to hire more professionals for that editorial check. “Relevance, rationally, quality and respect for legal rights” should be the critical aspects in the comment moderation, Oliveira put forward. Also in 2017, NRKbeta, the tech nological side of the Norwegian public broadcaster NRK, experimented a new type of commenting system5 in order to prevent abuses and hate speech. Before commenting, readers were asked to take a quiz to see if they actually read the story first; if the answers provided were mostly correct, readers could proceed into commenting. According to Marius Arnesen, editor of NRKbeta, inappropriate comments dramatically decreased over time: “You know when you write a really angry email, you should always like take a break, take a cup of coffee and then go back to that email, and maybe just think before you post it. This is our try to make the comments work in the same way”.

With the emerging social media commenting possibilities, media producers started to commute interaction features with their websites. This was the case of Spanish El Periódico, when, in 2013, allowed readers to comment using their Facebook and Twitter accounts. Nuria Llop, head of the digital section, considered that trolls would disappear “because you definitely do not want your friends to see your stupid comments in your timeline” (Ribeiro, 2013). No matter, the effective ness of this strategy, commenting news through social media is vastly common nowadays. Hille and Bakker (2014) studied 62 Dutch national and regional newspapers, public and commercial broadcasters, newsweeklies, national news programmes, and online news sites and found out that the majority news media “prefer outsourcing comments to Facebook although commenting on their own platforms is still possible” (2014: 563). Authors concluded that Facebook profiles linked to the news media websites typically discourage anonymous comments and abusive content.

3. Media producers and journalists’ perceptions on interactivity

Journalists and media producers’ views on interactive possibilities are far from consent. Following Chung’s (2007) previous research, media owners tend to feel interested in all suitable strategies to engage with audiences, but show important concerns with abuses and hate speech. In this regard, Nielsen (2012) also presented additional data, which showed journalists’ strong determination to continue promoting comments in news. However, there is doubts towards the idea of opening the gates with no supervision or guidance. In addition, this survey, which covered 36 newspapers, outlined that only 35% of journalists say they frequently or always read online comments on their stories.

Wolfgang (2018) defined journalists’ perceptions towards online commentators according to three possibilities: a basic support of comment policies driven by media administrations; perceiving com mentators as significant hazards to journalists, by a constant and harmful critique; a strong recogni tion of their role and importance (possible collaboration in stories, ability to correct aspects within texts). As the author explained, journalists tend to share positive views about commenting rather than negative ones.

In 2016, a report of the Engaging News Project at the University of Texas concluded that journalists are often curious about comments on their news stories; most of them considered that “[reading comments] is part of the job”. Consequently, most journalists feel legitimate to “hide, mask and delete” comments if basic rules of a discussion were not respected. Despite several abuses and bans, journalists defined comments as “reliable” and “positive”.

A different perception was shared by Gonçalves (2014), observing the tension between journalists and media producers when online comments management was at stake. Based on several case stu dies in Portugal, he observed that economic constraints and the insufficient number of professionals were the critical aspects within newsrooms to leave comment spaces with no moderation at all. In this study, the researcher quoted a journalist saying that online commenting was not a primary con cern for them; it was only an important matter for a small community.

Meyer & Carey (2013) stated that the increasing number of comments a newspaper receives, affects negatively in the journalists’ perceptions about their audiences and could discourage their partici pation in the online community formation. This analysis also suggested that audiences tend to feel more motivated to comment if journalists - mainly the news’ author - engages with them in the comment box. Kammer (2013) reminded former discussions of citizens’ intervention in the online news scope by proposing a simple distinction of “audience comment” and “audience content” based on, respectively, opinions and facts.

One possible explanation for shutting down comment section deals not only with the possible insuffi cient number of human resources to handle it, but also with growing fears that hate speech and poor quality comments may trigger negative social perceptions about this interactive tool. This article does not intend to analyse this particular dimension, but it is not possible to ignore such context. However, incivility in public spaces such as online news is more than common sense. Scientific research has empirically demonstrate it (Coe, Kenski & Rains, 2014). Løvlie, Ihlebæk and Larsson (2018) stated the experience of commenting is particularly meaningful for those whom oppose to a specific media outlet. Santana (2015) concluded that negative discourses in these spaces tend to increase towards immigration issues, based on a survey at sites of three online newspapers in Border States.

Kangaspunta (2018) studied commentators whom typically participate in public online spaces to misbehave and interact negatively. A social network analysis determined that these online users do not influence high-dense connections, as the majority of them participate on an individual basis. The author suggested an interesting point for future research in this area; promoting the understan ding of the context that surrounds internet bullies and troll farms, thus exploring social meanings for this type of audiences.

Ongoing debates have been undertaken to discuss the potential of audiences to engage with an exciting share of opinions, which reminds the ideal of a critical public sphere Habermas (1981) re markably proposed as both a scientific concept and a pragmatic vortex in our societies. For instance, Elisabeth Ribbans, The Guardian global readers’ editor, explained in April 20206“readers play a vital role in shaping the Guardian’s coronavirus content” as journalists often looked at all suitable and reliable “requests for stories of hope”. Moreover, audiences also feel triggered by constant mobilization to portable communication. Smartphones are one of the devices that have definitely challenged journalists’ practices, as well scholars to determine the expansiveness of news in present times (Aguado, Feijoo & Martínez, 2013). These objects of individualization often invite users to interact, engage, comment, transforming a single technical device a “home from home” concept (Casseti & Sampietro, 2002).

As part of an inspiration provide by the latest general set of theoretical insights, this article defines the following research questions:

Research Question 1 (RQ1): are comments to the online news available in the most acces sed mainstream news media in Brazil, Portugal and Spain?

Research Question 2 (RQ2): what kind of policies are being driven by mainstream media to address, allow and prevent/exclude audiences’ participation in the news stories?

Research Question 3 (RQ3): is it possible to consider that an originally based online me dia is better prepared - and particularly interested - in the promotion of in the online news participation, taking for granted that comments are a common feature in the digital media?

Research Question 4 (RQ4): what kind of innovative strategies - interactive tools - are being implemented to promote audiences’ participation in the comment spaces?

Research Question 5 (RQ5): is comment moderation - by media productions - frequent within these observed policies?

4. Methodology

Based on the previous discussion, this research follows the combined approach of a methodology both qualitative and quantitative (Matos, 2014), in the sense that it, in Social Sciences, and in the Communication Sciences scope in particular, quantification and interpretation are equally required at some level.

The universe of this research includes the overall news websites, with a particular focus on a journalistic approach. As such, this non-probabilistic sample collects data from The Reuters Ins titute Digital News Report 2019, with a focus in the most accessed news websites in the Iberian American countries Portugal, Spain and Brazil. In each country, we observed 15 online media outlets, with a background activity in journalism, in overall 45 cases studied. An experimental test like this (Stakes, 1995) is believed that the analysis provided by a careful examination shall determine similarities between the considered media, allowing researchers to address deeper and broader questions.

Furthermore, the main research technique consisted in a direct observation and textual/visual analysis (Quivy & Campenhoudt, 1995) of the sample’s websites, throughout news sections and spaces such as “Terms and Conditions”, where policies towards comments are explained in detail. The period of observation started in 15th May 2020 and ended in 22th March 2020. Considering the main research question of this study, several categories were elaborated to proceed into analysis:

Allowing comments: enabling or blocking, technically, comments in a website, especially regarding a particular news story;

Visibility of the comment icon: the technical feature - visual or textual - used to inform readers that commenting the news story is possible;

Place for comments: defining the space within online pages where comments are welcomed;

Comment box features: technical possibilities provided by media producers to write in the comment boxes, ranging from plain text to specific ones such as bold, italic, including links or adding photos;

Interaction features in the comment boxes: users may interact with each other in the com ment boxes, replying directly, sharing, reporting abuses, etc.;

Technical requirements to comment: observing media requirements for participation (re gistration onsite, via social media, e-mail, etc.);

Comment moderation: as defined in the theoretical framework, media organizations may implement strategies to prevent negative uses of commenting. Inspired by Littleton (2011), this category includes pre-moderation, post-moderation; a combination of pre and post mo deration; relying moderation to the community; other strategies;

Rules to comment: determining if media productions inform readers about the guidelines to comment and the level of visibility of such information;

Other aspects: remaining aspects not included in the previous categories, such as technical or innovative formats, for instance.

As to determine possible standards in media policies towards online commenting, this article sug gests another analytical tool inspired by previous research (Villi, 2012; Aguado, Feijoo & Martínez, 2013; Gonçalves, 2014; Piñero-Otero & Ribeiro, 2015). It is defined as “Media Policies for the Online News Commenting” model (MPONC). This model of measurement of policies argues that technical features, regardless their innovations and approaches, are important but also in serious commitment with regulation of comments and proper guidelines to interact in this participative format. This four-level model includes the following criteria:

High Standard - media institutions that have sorted out rules for participation, making them visible and aware;

Consistent - media institutions that, notwithstanding technical efforts and rules sound and clear, do not moderate online discussions;

Basic - besides no moderation, nor rules to participate, these media have failed in, at least, one of the following aspects: interactions provided in the comments, visibility of the com ment icon or even allow users to comment in the easiest way, through anonymous accounts enhanced by basic forms where only name and e-mail are requested;

Non-existent - media outlets that do now allow comments in their websites.

4.1 Study sample context

It is important to describe how audiences interact with digital and news media within the countries of the sample. Table 1 identifies some of those features:

Table 1 Audiences’ relationship with online media. Source: Digital News Report 2019

| Country | Internet Penetration | Trust in news | Paying for online news | Online news consumption | News comments (social media or web sites) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 71% | 48% | 22% | 87% | 36% |

| Portugal | 78% | 58% | 7% | 79% | 29% |

| Spain | 93% | 43% | 10% | 80% | 27% |

Portugal and Brazil present similar levels of Internet penetration, as Spain reaches a 93% hike. The percentage of trust in news is not impressive, although the Portuguese case may be a remarkable one - the second in the overall 38 cases. Brazilians tend to pay more for online news (22%), when comparing with other countries. The online news consumption is very close between the three cases - from 79% in Portugal to 87% in Brazil. There are no stark differences also in the participation in news comments, as values are close as well.

In an effort to characterize the type of online media in this sample, Table 2 presents two categories into observation: the original type of media organisation and the ownership.

This sample includes mainly exclusively online media (6 out of 15), but also newspapers (4), television (3) and radio (1), besides the case of BBC News Brazil which combines the latest two mentioned, as this broadcaster is the only public owned media in this group. With the exception of O Antagonista, which deals with politics, all the other ones are focused in a generalist type of journalism. Table 3 shows the Portuguese media outlets included in the sample:

Table 2 Main sources of online news in Brazil. Source: Digital News Report 2019

| Ranking | Media | Original type of media organisation | Ownership |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | UOL | Online | Private (Grupo Folha) |

| 2. | Globo News Online (G1) | Online | Private (Grupo Globo) |

| 3. | O Globo | Newspaper | Private (Grupo Globo) |

| 4. | Yahoo! News Brazil | Online | Private (Verizon Media) |

| 5. | Record News online | Television | Private (Grupo Record) |

| 6. | Folha de S. Paulo | Newspaper | Private (Grupo Folha) |

| 7. | MSN News Brazil | Online | Private (Microsoft Corporation) |

| 8. | SBT Notícias | Television | Private (Grupo Sílvio Santos) |

| 9. | BandNews FM | Radio | Private (Grupo Bandeirantes de Comunicação) |

| 10. | Terra | Online | Private (Grupo Telefónica) |

| 11. | O Estado de S. Paulo | Newspaper | Private (Grupo Estado) |

| 12. | BBC News Brazil | Television and Radio | Public (British Broadcasting Company) |

| 13. | RedeTV! | Television | Private (Grupo Amilcare Dallevo and Grupo Marcelo de Carvalho) |

| 14. | Extra | Newspaper | Private (Grupo Globo) |

| 15. | O Antagonista | Online | Private (Empiricus Research) |

Table 3 Main sources of online news in Portugal. Source: Digital News Report 2019

| Ranking | Media | Original type of media organisation | Ownership |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Correio da Manhã | Newspaper | Private (Cofina) |

| 2. | Notícias ao Minuto | Online | Private (New adVentures, Lda) |

| 3. | SIC | Television | Private (Impresa) |

| 4. | Sapo | Online | Private (Altice Portugal) |

| 5. | TVI | Television | Private (Media Capital) |

| 6. | Jornal de Notícias | Newspaper | Private (Global Media) |

| 7. | MSN Portugal | Online | Private (Microsoft Corporation) |

| 8. | Observador | Online | Private (Observador On Time, S.A.) |

| 9. | Público | Newspaper | Private (Sonae) |

| 10. | Expresso | Television | Private (Impresa) |

| 11. | Correio da Manhã TV | Television | Private (Cofina) |

| 12. | Diário de Notícias | Newspaper | Private (Global Media) |

| 13. | RTP | Television and Radio | Public (RTP) |

| 14. | A Bola | Newspaper | Private (Sociedade Vicra Desportiva) |

| 15. | Dinheiro Vivo | Online | Private (Global Media) |

In terms of the original type of media, this is an interesting balanced sample: five media outlets exclusively online, five digital versions of newspapers and four from television. The ownership of the Portuguese media shows some worrying level of concentration (Silva, 2014), especially because some large media corporations practically dominate the market. Except A Bola, a sports journalism media, and Dinheiro Vivo, in economics, all the other ones are focused in a generalist type of jour nalism. Table 4 shows the Spanish media included in the sample:

Table 4 Main sources of online news in Spain. Source: Digital News Report 2019

| Ranking | Media | Original type of media organisation | Ownership |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | El País | Newspaper | Private (Grupo PRISA) |

| 2. | El Mundo | Newspaper | Private (Grupo Unidad Editorial) |

| 3. | Antena 3 | Television | Private (Atresmedia Corporación) |

| 4. | El Diário | Online | Private ( Diario de Prensa Digital S.L) |

| 5. | 20 Minutos | Newspaper | Private (Grupo 20 Minutos) |

| 6. | El Confidencial | Online | Private (Titania Compañía Editorial, S.L) |

| 7. | Marca | Newspaper | Private (RCS MediaGroup) |

| 8. | La Vanguardia | Newspaper | Private ( Grupo Godó) |

| 9. | Telecinco | Television | Private (Mediaset España Comunicación) |

| 10. | OKDiario | Online | Private (Dos Mil Palabras SL) |

| 11. | La Sexta | Television | Private (Atresmedia Corporación) |

| 12. | ABC | Newspaper | Private (Vocento) |

| 13. | El Periódico | Newspaper | Private (Prensa Ibérica and Grupo ZETA) |

| 14. | RTVE | Television and Radio | Public (RTVE) |

| 15. | Yahoo! España | Online | Private (Verizon Media) |

Digital versions of newspapers dominate the most access online source of news in the Spanish case (7). There are only four exclusively online outlets and three televisions websites. Private sector is the most represented one in the media ownership. Except Marca, which is preferably interest in sports, all the other ones are focused in a generalist type of journalism.

At last, media concentration seems to impact differently across countries. Brazil and Portugal share the same perspective, though. Grupo Globo (with 3 media outlets) and Grupo Folha (2) dominate one third of the market share in the most accessed websites in Brazil. In the Portuguese case, si milar options are visible, because Global Media (3), Cofina (2) and Impresa (2) clearly control the market. The Spanish case shows that media ownership is not so much concentrated, as no company dominates one part of the market.

5. Results

In a general assessment, it is possible to consider that each country introduces different approaches to the online news commenting, which is consistent with some of the theoretical aspects highlighted in the literature review. The following tables (5 - 7) express the overall evaluation of the sample according to the direct observation criteria regarding online comment policies:

Table 5 Observation of the comment policies in the Brazilian media sample

| Media | Allowing comments | Visibility of the comment icon | Place for comments | Comment box features | Interaction features | Technical requirements to comment | Comment moderation | Rules to comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BandNews FM | Yes | No | Box after the news | Plain Text | Reply | Basic form (name, e-mail) | None | No |

| BBC News Brazil | No | No | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Extra | Yes | No | Box after the news | Plain Text | Reply; Like; Dislike; Report | Google, Facebook, onsite | None | Yes, visible |

| Folha de S. Paulo | Yes | No | Box after the news | Plain Text | Reply; Like; Report | Google, Facebook, onsite | None | No |

| Globo News Online | No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| MSN News Brazil | No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| O Antagonista | No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| O Estado de S. Paulo | Yes | No | Box after the news | Plain Text | Respect; Reply; Share; Report | Subscription account | None | Yes, not visible |

| O Globo | Yes | No | Box after the news | Plain Text | None | Subscription account | None | Yes, visible |

| Record News | No | No | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RedeTV! | Yes | No | Box after the news | Plain Text | Reply; Like | Facebook account | None | No |

| SBT Notícias | No | No | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Terra | Yes | No | Box after the news | Plain Text | Reply; Like | Facebook account | None | No |

| UOL | Yes | No | Box after the news | Plain Text | Reply; Like; Report | Google, Facebook, onsite | None | Yes, visible |

| Yahoo! News Brazil | Yes | Yes | Box after the news | Plain Text | Reply; Vote; Like; Dislike; Report; Silencing | Yahoo account | None | No |

Table 6 Observation of the comment policies in the Portuguese media sample

| Media | Allowing comments | Visibility of the comment icon | Place for comments | Comment box features | Interaction features | Technical requirements to comment | Comment moderation | Rules to comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Bola | Yes | No | Box after the news | Plain Text | Report; Like; Dislike | Onsite account | None | Yes, visible |

| Correio da Manhã | Yes | No | Box after the news | Plain Text | None | Basic form (name, e-mail) | Unknown | Yes, no visible |

| Correio da Manhã TV | Yes | No | Box after the news | Plain Text | None | Basic form (name, e-mail) | Unknown | Yes, no visible |

| Diário de Notícias | Yes | No | Box after the news | Plain Text | Reply; Like | Facebook account | None | Yes, no visible |

| Dinheiro Vivo | Yes | No | Box after the news | Plain Text | Reply; Like | Facebook account | None | Yes, no visible |

| Expresso | No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Jornal de Notícias | Yes | No | Box after the news | Plain Text | Reply; Like | Facebook account | None | Yes, no visible |

| MSN Portugal | No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Notícias ao Minuto | Yes | No | Box after the news | Plain Text | Reply; Like | Facebook account | None | Yes, visible |

| Observador | Yes | Yes | Box after the news | Bold, italic, link, quotes, bullets | Vote; Reply | Google, Facebook, onsite | None | Yes, no visible |

| Público | Yes | Yes | Box after the news | Plain Text | Reply; voting | Google, Facebook, onsite | Yes | Yes, no visible |

| RTP | No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sapo | Yes | No | Box after the news | Plain Text | Reply; Like | Facebook account | None | No |

| SIC | No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| TVI | No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Table 7 Observation of the comment policies in the Spanish media sample

| Media | Allowing comments | Visibility of the comment icon | Place for comments | Comment box features | Interaction features | Technical requirements to comment | Comment moderation | Rules to comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 Minutos | Yes | No | Box after the news | Bold, italic, add links, add other commentators nicks | Reply; Like; Share; Report | Onsite account | None | No |

| ABC | Yes | Yes | Box after the news | Plain Text | Reply; Vote; Like; Dislike | Google, Facebook, onsite | Yes | Yes, not visible |

| Antena 3 | No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| El Confidencial | Yes | Yes | Box after the news | Bold, italic, underlined, add links | Reply; Like; Dislike; Report | Google, Facebook, LinkedIn | None | Yes, visible |

| El Diário | Yes | Yes | Box after the news | Plain Text | Reply; Like; Dislike; Report; Silencing | Google, Facebook, Twitter, onsite | None | Yes, visible |

| El Mundo | Yes | Yes | Box after the news | Plain Text | Reply; Like; Dislike; Report | Google, LinkedIn, onsite | Yes | Yes, not visible |

| El País | Yes | Yes | Box after the news | Bold, italic, add images | Reply; Share; Like; Dislike; Report | Google, Facebook, onsite | Yes | Yes, visible |

| El Periódico | Yes | Yes | Box after the news | Bold, italic, underlined, strikethrough, add links, quote, add paragraph | Reply; Vote; Share; report | Google, Facebook, onsite | None | Yes, not visible |

| La Sexta | No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| La Vanguardia | Yes | Yes | Box after the news | Plain Text | Reply; Vote; Like; Report | Google, Facebook, onsite | None | Yes, visible |

| Marca | Yes | Yes | Box after the news | Plain Text | Reply; Vote; Like; Dislike; Report | Facebook, onsite | Yes | Yes, not visible |

| OKDiario | Yes | No | Box after the news | Bold, italic, underlined, strikethrough, add links, quote, add paragraph | Reply; Vote; Share | Google, Facebook, Twitter, onsite | None | Yes, visible |

| RTVE | No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Telecinco | Yes | No | Box after the news | Plain Text | None | Facebook, onsite | None | Yes, not visible |

| Yahoo! España | Yes | Yes | Box after the news | Plain Text | Reply; Vote; Like; Dislike; Report; silencing | Yahoo account | None | No |

6. Data analysis and discussion

Spanish online media seem to be very distinctive in the promotion of solid and high standard poli cies towards online commenting. According to the first criteria, the majority of the websites allow comments: 31 out of 45. Spanish media (12 from 15) include the possibility of commenting, in contrast with 10 in the Portugal and nine in Brazil.

Regarding the second criteria - the level of visibility of comments - 9 out of 12 Spanish media include a specific icon, close the news title, showing users that comments are possible. Only two media, in Portugal, and one, in Brazil, follow this very same idea. We must assess that this technical possibility does not guarantee that online readers feel automatically motivate to comment nor validates a positive participation. It ensures, in a minimum level, that sharing some particular view on a topic is possible.

In the third category of the observation remains the core of this type of participation: comment boxes. Where are comments displayed? What kind of technical features are available? Are comment boxes appellative, innovative or just simple plain text ones? Firstly, all comments to the news are placed at the bottom of the webpage. The exception of an innovative approach is provided by the Brazilian outlet Extra, thus showing comments at the top of the page, as shown by Figure 1:

Most of the media engage with readers through these comments spaces using simple plain text boxes. This is the case of the Brazilian and the Portuguese samples, although Observador offers boxes with bold, italic and adding quotes. In Spain, no changes were found (7/12), however 20 Mi nutos, El Confidencial, El Periódico and OKDiario seem to be inventive, by allowing users to write comments using bold, italic, underlined, strikethrough text, as well, adding links, quotes, and other commentators nicks. Of course, this is more like a technical, visual aesthetics dimension of this analysis, and even the most distracted evaluation suggests that most of the commentators simply add a plain text in the box.

Subsequently in the fourth category, it was observed how readers’ comments can be interactive themselves, thus allowing users to reply directly to a specific intervention, share one point of view, including the latest hot-topic features like-dislike, as well as reporting potential speech abuses (spam, offensive content, insults, off topic issues, etc.). Very limited media do not offer interaction tools - only O Globo (Brazil) and Telecinco (Spain). Replies are the most common feature in the comment boxes, meaning that users can interact directly in these spaces. Share, like and dislike comments, reminding us some social media lexical ecosystem, are also frequent. These are the most common tools both in the Portuguese and in the Brazilian scope. Spanish online media take one-step higher in this interactive model within comment boxes and widely promote other types of participation, such as vote and report.

The fifth concept integrated in this observation deals with the evaluation of technical requirements to comment. This is crucial, because it determines how complex is to add a comment. Abuses may be frequent if comments is easy, one could speculate, although making these doors harder to open does not suggest that abuses disappear. In this sample, there are only three cases of this so-called “easy participation”, from a technical point a view. BandNews FM (Brazil), Correio da Manhã and Correio da Manhã TV (Portugal) allow comments by granting users a basic requirement of adding a possible name and e-mail (not verified) after the comment is completed. The comment is posted af terwards. This is a very fragile procedure in the way handling commentaries is held. Regardless this option, most of study object prefer to ask users for a specific registration before posting a comment. The most common one is through a Facebook account (18 cases), Google (13 cases) and a registra tion in the website (15 cases). It is possible to find very specific examples where commenting is only possible if users subscribe (pay, in these cases) and get access to all spaces in that website. This is a very complex strategy, probably a not very enticing one for abusers, but happens in O Estado de S. Paulo and O Globo, both in Brazil. Spanish media include LinkedIn and Twitter accounts to be linked with the comment section, other distinctive aspect in this analysis.

In terms of how comments are displayed in these interactive boxes, most of the analysed media present the list of contributions according to the latest published one. However, some of them present comments in folders (most voted; all comments; most replied, etc.). This is the case of O Estado de S. Paulo, La Vanguardia, Observador, etc. This is probably a segmentation tool based on comments’ relevance to promote a (potential) healthy space for comments. El Mundo and El País include a particular folder where users have the possibility to check the participants whom have comment her/his previous comment - it is called “mentioned comments”.

Brazilian media outlets Terra and RedeTV promote spaces for commenting using a Facebook login, but adding a particular feature in this sense: users may tick a box preventing the comments to be visible on Facebook. In Portugal, both Correio da Manhã and Correio da Manhã TV allow anony mous comments. El Mundo decided to harden the registration process before commenting by asking users a personal nick to comment and a captcha form to be solved, hence preventing attacks from boots and other harmful informatics dynamics. In El Diário premium readers (paid subscription) have a specific comment badge.

Regarding media intervention in the comment section, this is probably the most intriguing aspect and even disturbing as no definitive policy is undertaken to avoid abuses in commenting. No mode ration is undertaken in the Brazilian and Portuguese samples, which means that users may publish a comment after a suitable (if necessary) registration. Comments are then published right away. This does not represent that media institutions are dismissing their role as mediators - the majority argue in their “Terms and Uses” information guidelines that “comments are likely to be banned if they are offensive. Nevertheless, there is no verification of the comments’ credibility before posted public. In the Spanish cases, the majority does not check either, but ABC, El Mundo, El País and Marca prefer to have the comments read before posted online (the pre-moderation model Littleton propo sed). We believe that this situation depends on the human resources within newsrooms to perform this task accordingly. This suggests that commenting, in these spaces, is harder, which is a powerful message for trolls and abusers.

Within this sample, it must be highlighted the innovative approach of Público from Portugal. Com ment moderation is based through rankings and votes readers share among them. This is consistent with the fourth model proposed by Littleton (2011). Regardless this apparent self-regulation, jour nalists of Público are entitled to ban comments if abuses are found. The system is based on an esca lating reputation from beginner, moderator to experienced contributor. Only positive evaluations by others may help commentators climb the ladder of reputation progressively. Every user has his/her own reputation exclusively based on the number of interactions within the community: commenting and moderating other interventions. Approving one comment, for instance, may contribute for one’s evaluation, in the exact same amount if a person is ticketed by the report icon for potential abuses. Readers are also welcome to promote their own forums from a specific online news7.

As a consequence of the latest item of observation, it is important to evaluate if guidelines for par ticipation in the comment spaces are visible for readers. We must stress out that rules to participate are no perfect medicine for abuses, but norms and transparency may have a positive effect on users’ perceptions of online commenting. Taking into account that 31 online media of this sample allow comments in their webpages, 22 have guidelines for participation: 4/9 (Brazil), 9/10 (Portugal) and 9/12 (Spain). Very few media clearly indicate the guidelines to comment. Rules of commenting are only perfect accessible in eight media - four in Spain. No specific textual analysis was carried out to evaluate the rules of each media towards online commenting, but three common aspects emerge: 1) readers’ opinions and comments do not represent the view of institution; 2) poor quality comments include: racism, sexism, homophobia, hate-speech towards race, religion, sex, gender, sexual orien tation, disability or age; 3) relevant comments should include informed and honest contributions.

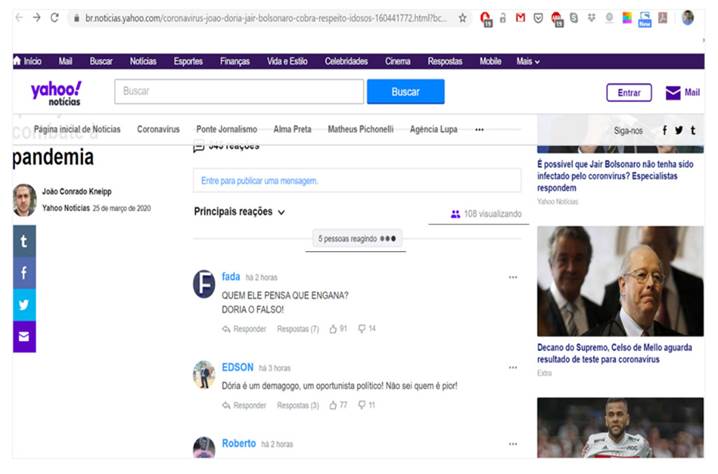

Finally, the last criteria includes levels of analysis not included in the previous observation. In the comment section of Yahoo News - in both Brazil and Spain - it is possible to check how many users are preparing their comments and the number of visualizations of that piece of news (Figure 2).

This technical feature shows somehow the level of mobilization that some news may present, thus motivating commentators to engage in the discussion. It is more like an instantaneous communication

Figure 2. Overview of the comment section in Yahoo News, who is reacting view [underlined]

As suggested by the methodological procedure, the MPONC model - Media Policies for the Online News Commenting - seeks to analyse a different set of features within media websites in the sam ple, according to a four-level ranking: 1) High Standard; 2) Consistent; 3) Basic; 4) Non-existent. Having in mind these criteria, Table 8 was assessed:

Table 8 points out that Portuguese and especially the Spanish online media promote wider chances for users to interact with news. It is noteworthy how a significant amount of online media - we should recall that these are the 15 most accessed online media in each country - clearly do not engage with readers through online comments. As mentioned earlier, Spain seems to be the most suitable case to find reliable policies driven to integrate of comments in the news.

The proportion of each scale per country presents the following data: non-existent policies (6 - Bra zil; 5 - Portugal; 3 - Spain); basic polices (5 - Brazil; 3 - Portugal; 3 - Spain); consistent policies (4 - Brazil; 6 - Portugal; 5 - Spain); high standard policies (0 - Brazil; 1 - Portugal; 4 - Spain).

Concluding, the observation criteria and the MPONC model provided helpful information to ad dress the research questions. In doing so:

Research Question 1 (RQ1): A significant part of online media still does not allow com ments at all - 14 out of 45. This outcome is not consistent with Liu and McLeod (2019) as sessment, regarding the total comment withdrawal of biggest online media, but is very clear on the multiple understanding and social value given to online comments;

Research Question 2 (RQ2): as policies differ, MPONC model suggests that Spain (the most distinctive case) and Portugal typically implement consistent/high standards policies for online news commenting. Brazil presents no high standard policies and a significant non-existent level in this regard;

Research Question 3 (RQ3): based on the MPONC model, it is possible to conclude that originally based online media are better prepared for commenting interactive possibilities. In fact, six out of 14 of them carry out consistent policies. According to the type of media, four newspapers are included in the high standard level and television broadcasters seem to ignore these possibilities - eight of 13 do not allow comments.

Research Question 4 (RQ4): not many innovative strategies are followed in the sample.

Comment boxes are very similar in a technical point of view, although some media inclu de the possibility to add images or links to comments, but readers seem to comment using words. Comments are visible only at the bottom of the webpage, excepting the case of Brazi lian Extra, featuring comments in the top of the page. Innovation may deal with moderation strategies, as Portuguese Público presents a different approach.

• Research Question 5 (RQ5): comment moderation is also a category that enlists the alre ady-mentioned divergence in this scope. Media institutions prefer not to moderate (review) comments and ban possible participation afterwards.

7. Final remarks

Media companies face countless challenges with their busy online commenting sections. Stroud, Duyn and Peacock (2016) have shown high rates of public attention in these spaces. However, several public discourses have broaden a negative social image of comments: “hate and prejudice, trolling and flaming, with users that speak more than they listen, frustrating the desire for rational consensus” (Carpentier, Melo & Ribeiro, 2019: 19). Not only online comments have a negative reputation. Participation, as an autonomous concept within the Communication Sciences concept, is frequently regarded as an instrument of harmful and symbolic violence. Claims of public opinion manipulation label some of those perspectives as well.

This article did not emphasize the substantial dimension of comments, which could be an inte resting area for future research. Nevertheless, it does focus on the media policies towards online commenting, concluding that technical aspects and guidelines to participate may not be sufficient for a healthy digital space.

Although the majority of the websites leave comments available - 31 out of 45 -, there is still an important part of media that ignore this interactive feature. Questioning reasons behind those deci sions shall emerge as a research topic in future endeavours. It is somehow curious the way media promote the possibility of commenting; very few make comments visible and attractive. The same tendency when it comes to place the comment section, always allocated at the bottom of the web page, which we could describe as consistent with some sort of invisibility of commenting, at least in a visual point of view.

The comment boxes seem also very similar in most cases: plain text and interaction within those spaces is related to reply directly, sharing, like and dislike comments. Voting or report abuse are less frequent, though. Accessing to comments raises other kind of concerns. Three media leave com ment sections open, with no moderation or registration required; nonetheless, commenting using a social media login is the most common tool.

This research also points out very limited options to promote innovation in comment sections. Some media - O Estado de S. Paulo, La Vanguardia, Observador, Público, El Mundo and El País - highli ght most voted (or ranked) comments in particular spaces, which it could be understood as a way to promote specific spaces where a rational and fruitful discussion may be enhanced. Portuguese Públi co allows readers to create their own forums in the very same news story, a mature and accountable strategy handed by the media to the audiences. Regarding moderation, one of the key elements in the media policies, this article acknowledges this troubling aspect, as it is stated very clearly that most media ignore such possibility and/or do not possess the ideal staff conditions to do it accordingly.

Furthermore, future research should be able to map continually these policies, hence analysing if media administrations reinforce/discourage this type of interaction. It would be interesting to learn if high standard polices media, following the Media Policies for the Online News Commenting mo del, are the most suitable place for comments, thus evaluating if the quality of commenting depends on the quality of the policies.