1. Introduction

Nowadays, in Western countries, we can breathe the aroma of controversy and the feeling of combining the media with privacy, especially regarding social causes. Cyberactivism movements, which emerged on social networks, continue to inform and call users to action in order to generate a social response, especially in the face of cases in which the dignity of minorities is attacked, especially since 2013, the year of the emergence of the Black Lives Matter (#BLM) movement, and since 2017, with the #MeToo movement. #BLM started after the acquittal of George Zimmerman for the murder of the African-American teenager Trayvon Martin. At the same time, the #MeToo movement emerged after the denunciations of women, especially actresses from the world of cinema, who denounced the producer Harvey Weinstein.

This image of vindication, support, and call to action that has emerged in recent years reflects the spirit of the millennial and centennial generations, who often identify themselves as anti- racist, feminist, and anti-fascist. They reject old-fashioned prejudices related to gender and race, seeking a sense of social change. In addition, they are very attached to technology (Fuenmayor & Aranguren, 2018, p. 65). This is how the Internet, and most especially social networks, have turned what was a space for entertainment into a place where people have gone from acting in a «collective» way to one in which they proceed in a «connective» way (Candón-Mena & Montero-Sánchez, 2021).

However, these cyber movements can bring a feeling of censorship and ideological dogmatism, encouraging the act of «canceling» public figures, companies, or political parties. The woke culture and the so-called «cancellation culture» are, in the name of participatory digital cultures, increasingly booming thanks to the establishment of the technological ecosystem in which we are immersed, fostering trust towards the manifestations initiated by users of social networks, resulting in the attack against those public figures who break with what is socially acceptable (Velasco, 2020).

In the case of movies and TV series, which are more democratized than ever thanks to OTT platforms, there have been attempts of censorship, as can be seen in the case of the classic film Gone with the Wind (1939) after the murder of George Floyd or a «prior apology», which appears in the prologue of the Disney film Fantasia (1940) when starting its reproduction on the Disney+ platform due to the racist scenes that existed in the feature film at the time of its release. Thus, we glimpse that we are at a time when forms of entertainment consumption and avenues of political vindication are changing.

Likewise, we find diverse examples today: A Tennessee parish priest held a burning of “witchcraft” books, including copies of Harry Potter and the Twilight Saga, in early 2022 (The HuffPost / EFE, 2022). The same year, the comic book Maus was removed by the decision of the McMinn County school board from the list of Art and Language books for eighth graders due to complaints from a group of parents who detected “eight swear words and the drawing of a nude”. Additionally, parents confirmed feeling offended by the presence of themes relating to suicide or the killing of children (Moran, 2022). We have also seen calls for narrative changes in social networks, such as the massive disappointment experienced after the last episode of Game of Thrones, the physical appearance of Lola Bunny in Space Jam 2, or the character Sonic in its film adaptation (changed after the poor reception of the trailer), as well as the controversies with the alleged misogyny of the film Blonde (2022) by Andrew Dominik (Moran, 2022).

Therefore, new questions are being raised today that combine morality and audiovisual content consumption, such as whether the criminal or moral history of any member who has participated in filming a movie or series is a determining factor. For example, Woody Allen and Roman Polanski have been accused of child abuse, Kevin Spacey of sexual abuse, Lars von Trier made a joke praising Hitler, Walt Disney was anti-Semitic, a Twitterer (a columnist for the newspaper El Tiempo [Colombia]) complained on social networks that J.R.R. Tolkien had not added female and African-American diversity in The Lord of the Rings (Redacción Alma Máter, 2022); Patricia Highsmith made anti-Semitic statements and J.K.Rowling is accused of transphobia by a series of published tweets, so the actors of the saga have publicly disowned her. One of the big questions today is whether the audience considers it ethical to watch audiovisuals labeled as immoral at any stage.

According to Rizzacasa d’Orsogna (2023), classic authors such as Homer, Ovid, Mark Twain, Plato, J.R.R. Tolkien, Margaret Atwood, J.K. Rowling, Philip Roth, Harper Lee, Ernest Hemingway, Walt Disney, John Steinbeck, Hergé (sued in a Belgian court for the “racist content” of Tintin in the Congo in 2011)1 have currently suffered cancellations in the United States. According to Timón Herrero (2020, p. 219), when the sense of humor is lost, “the criteria for evaluating artistic content end up being limited either to personal tastes (which is irrelevant) or to the personal feeling of offense that it has caused in the viewer”. However, beyond the United States, such requests are also felt, albeit somewhat weaker, in other Western countries. In 2017, at the University of London, the Oriental and African Studies student union called for the exclusion of Plato, Descartes, or Kant from the philosophy curriculum for being “white philosophers” as well as “racist and colonialist” (Marirrodriga, 2017; Fernández-Rodríguez & Castillo-Abdul, 2022, p. 496).

In this sense, it is worth asking whether viewers consider that protesting on social networks should serve to change those things that they consider unfair in an audiovisual production (for example, the treatment of a minority group) and whether they believe that these mechanisms should be used so that audiovisual studios can listen to the audience, taking into account their opinion as consumers, even if this means socially censoring content and affecting the freedom of expression.

As a starting hypothesis, therefore, it is considered that audiences feel and have a certain predisposition to demand from audiovisual creators that, in the name of the recent clientelist empowerment, and not of art or narrative as it could have been a few years ago, a narrative must be changed in order to please them. Taking all of the above into account, the objective of this research is to examine the psychosocial feeling of political efficacy that millennials and centennials have as audiences of movies and series on streaming platforms in Spain and Mexico, with respect to the audiovisual narratives they consume, in order to determine their predisposition and justification to prioritize their viewpoints in the face of censorship of audiovisual content. To this end, the following Research Questions (RQ) arise:

RQ1: What is the level of political efficacy that viewers consider to have with respect to the belief of being able to influence the audiovisual narratives they consume?

RQ2: Are there differences in this sentiment between millennial and centennial audiences?

RQ3: Is the political ideology with which spectators identify a variable affecting the perceived level of efficacy?

RQ4: Are there significant differences in self-perceived efficacy in relation to gender, country, and educational level of viewers?

This research aims to identify how the ideology and empowerment younger viewers perceive themselves to have over the movies and series that are so present in their routines. According to Rizzacasa d’Orsogna (2023, p. 12), for the last thirty years, a culture of cancellation has been forged in American universities that pushes the United States to “rethink its literary canon, and of many other things, in light of political correctness.” Consequently, we wonder if this may happen in other places, such as Spain and Mexico (the Spanish-speaking countries that consume the most streaming). That is, whether they have a high level of political efficacy in modifying the fiction narrative they consume.

1.1 Political attitudes and psychosocial sentiment of efficacy

The observation of political attitudes has been of great academic interest since researchers began attending them in the 1950s (Morrell, 2003). Political efficacy first appeared in Campbell, Gurin, and Miller’s The voter decides (1954) and was defined as the feeling that political and social change is possible and where the citizen acting as an individual has the power to play a role in bringing about this change (Campbell et al., 1954; Kenski & Jomini, 2010).

Political efficacy is a psychosocial variable based on the subjective belief of an individual or group that they possess sufficient capacity to participate in and influence the course of political events (Klesner, 2003). Similarly, it was defined as a unidimensional construct that was measured with four items of agreement-disagreement and has undergone an evolution that, according to Morrell (2003, p. 590), can be summarized as follows: NOSAY (“People like me have nothing to say about what the government does”), COMPLEX (“Sometimes politics and government seem so complicated that a person like me cannot really understand what is going on”), VOTING (“Voting is the only way people like me can have a say in how the government runs things”) and NOCARE (“I do not think public employees care much about people like me”). However, between 1968 and 1980, two more items appeared, proposed by the American National Election Studies (NES) (Morrell, 2003, p. 590): CONGRESS (“In general, those we elect to Congress in Washington quickly lose touch with the people”) and PARTIES (“The parties are only interested in people’s votes, but not in their opinions”).

According to Kahne & Westheimer (2006), internal political efficacy refers to a person’s sense of being able to participate effectively in the political process. Hence, people with high internal political efficacy believe they can participate in and influence civic affairs more. On the other hand, external political efficacy reflects the perception that the government is responsive to the citizenry’s demands. Although political efficacy has been studied since the 1950s, researchers seem to disagree on correctly measuring it. After much testing, six new questions on internal political efficacy were added to the 1988 US National Election Study. These six new internal efficacy items tested in 1987-88 were (Niemi et al., 1991;Morrell, 2003): SELFQUAL (“I consider myself well qualified to participate in politics”), UNDERSTAND (“I consider that I have a fairly good understanding of the important political issues facing our country”), OTHERS (“It seems that other people find it easier to understand complicated topics than I do”), PUBOFF (“I feel that I could do as good a job in public service as most people do”), NOT SURE (“I often feel unsure of myself when talking to others about politics and government”) and INFORMED (I think I am better informed about politics and government than most people”).

Therefore, internal political efficacy has mainly remained stable since the late 1960s, while external political efficacy has steadily declined (Sullivan & Riedel, 2001). Moreover, both parts of political efficacy are relatively stable globally. However, the two relate differently to the individual: While internal political efficacy relates to changes in the socioeconomic environment and the individual’s life stage, external political efficacy is more sensitive to changes in the political environment and, in many cases, ignores the characteristics of the individual. As is logical, political efficacy has been generally identified as a measure of democratic health (Valera, 2013). However, the crisis of Western democracies, which began with the economic crisis of 2008, seems to have generated a great disaffection towards politics in general:

Real democratic systems have been unable to satisfy some of the fundamental propositions of the theory of democracy and exhibit severe pathologies in their contemporary implementation: the survival of «invisible power» or fundamental lack of transparency and openness, the persistence of oligarchies, the prevalence of groups over individuals in the political space, the renewed vigor in the representation of private interests, the collapse of citizen participation and the failure of democratic regimes in the civic education of citizens (Valera, 2013, p. 60).

In addition, the concept of political efficacy has historically been related to socioeconomic status, education, and the ethnic majority (Sullivan & Riedel, 2001; Prewitt, 1968). Currently, both internal and external efficacy levels are lower among European individuals suffering from depression, concluding that “depression is related to lower external efficacy” (Bernardi et al., 2022, p. 23). Beyond mental health, other problems today, such as the political class’s poor handling of climate change, encourage Western individuals to perceive less political efficacy. Similarly, according to Dirksmeier & Tuitjer (2022), using renewable energy increases the perceived personal efficacy of politics, even giving a «symbolic value» to renewable energy infrastructure. All of this demonstrates that political efficacy is one of the most important determinants of political actions since a person’s internal perception of external reality affects his or her perception of control over his or her own life (Bene, 2020). If people perceive that they can effectively shape political processes, they will be more likely to carry out and externalize actions of a political character.

In this process of trust or distrust towards the political class, the media are part of the problem: according to Bene (2020), the higher the media presence in political discourses, the “less receptive” citizens will perceive the political system. In short, how the political reality is presented in the media can damage the perception of the political system, with the so-called «surveillance journalism» going from being seen exclusively as a crucial weapon of politics in democracy to reflecting a democratic danger since it risks alienating voters from the political system and its actors. In the same spirit, according to Shore (2020), political efficacy is also an important factor for social equality since social policies often have relevance for vulnerable groups, fostering, as a consequence, the perception of the individual as part of political life, as well as his or her ability to influence it.

1.2 Cancellation culture, the «woke» movement, and cyberactivism

Contemporary censorship in film and other arts can transfer this debate to the term «woke», currently a growing doctrine in the United States and some European countries. According to Muñoz-Rojas (2021), this movement has echoes throughout the West, so in 2017, the Oxford Dictionary included this term in its list of neologisms defining it as “alert to racial or social discrimination and injustice”. However, this «alertness» has ended up in many cases deriving in the so-called «cancellation culture», which, although it seems primarily current, already gave some signs of life in the 1990s.

Following Burgos & Hernandez (2021), the real massification of this concept came in 2010, when Black Twitter was created, the well-known network of users of the African-American community in the United States whose goal was to report the facts of racial discrimination. Similarly, since 2017, the year of the emergence of the #MeToo cyber-movement, the «cancellation culture» also generated cancellations of public figures accused of having committed physical and psychological violence, sexual harassment, and misogynist behaviors in the Hollywood industry.

The official cancellator is a very astute avenger. He or she hides behind democracy and freedom of expression, pretends to be a moral subject, and speaks of justice, the rule of law, and rhetoric to captivate followers. He or she has thousands, millions of followers. He or she is a digital being, viral and charismatic. Influence and trend. Globalizes harmful content. It damages reputations. It highlights the plurality of ideas and, thus, cultural diversity (Burgos & Hernández, 2021, p. 145).

In recent years, given the development of the fruitful relationship between society and technology, new collectivities have been formed through social networks that have paved the way for the emergence of participatory digital cultures and social movements, turning the act of «canceling someone» into one of the spontaneous collective practices initiated by social network users, without taking into account its possible ramifications, thus attacking those public figures who break the norms of social acceptability (Velasco, 2020), in a sort of «spiral of silence». Cancellation culture has the power to deconstruct anyone’s life at any time. It can be directed at a public figure who has offended a minority, as most people canceled are often accused of harassment, sexism, racism, or homophobia. However, this concept is not limited exclusively to individuals, as companies, political parties and ideas, social movements, and even audiovisual productions can also be canceled (Mueller, 2021, p. 1).

The cancellation culture is also evidence of how digital platforms have facilitated rapid responses on a global scale to problematic acts related to traditionally marginalized groups at the time, highlighting the absence of thoughtful evaluations and debates (Ng, 2020, p. 625). Likewise, the concept of canceling someone out is specifically designed for the digital age, flouts open debate, and comes across as a form of destructive criticism (Velasco, 2020, p. 6). Cyberactivism is thus a matter of importance from a communicative point of view. According to Candón- Mena & Montero-Sánchez (2021), the dominant technopolitical orientations, concerning the use of ICTs for collective actions, during specific periods can coexist, reinforce each other or adapt to different contexts, being these the most relevant functions to detect such orientations: pragmatic/utilitarian, strategic/tactical, ideological/identity-related.

For example, it is not surprising that Black Lives Matter or the #MeToo movement have much of their roots in the critique of the audiovisual representation of African American or female suffering as one of their central thrusts of action. Black Lives Matter (BLM) began as a rallying cry and a movement intended to galvanize communities to demand an end to social injustices within the US criminal justice system (Black Lives Matter, 2015; Sobande, 2021; Sullé et al., 2021, p. 2; Sutherland, 2017). The term «woke» is linked to African-American consciousness and racial struggles, as the slang was first used at the end of a recording of the 1938 popular protest song “Scottsboro Boys” by Lead Belly. That theme song refers to the case of nine young black men falsely accused of raping two white women whose lives were destroyed by the Alabama justice system. At the song’s end, Belly warned them to be careful when passing through Alabama: “you better stay awake, keep your eyes open” (Cammaerts, 2022, p. 4).

Returning to the present, the labor and image of African Americans are being astutely exploited and reframed as part of the digital marketing strategies of those brands seeking to position themselves as “wokes.” In other words, a new kind of digital racism invites us to examine how “racial capitalism and the commodification of black social justice movements drives such oppression” (Sobande, 2021, p. 133). In this way, using networks to articulate action has been experienced for a few years. However, it has become increasingly consolidated and can be of two types: if the action networks involve formal institutions or organizations, we speak of

«collective action», but if we refer to self-organized organizations, we speak of «connective action». For example, in recent years, it could be observed how social movements, such as 15-M in Spain, Occupy Wall Street in New York, BLM or #Metoo, are increasingly closer to the more evolved logics of action of self-organized networks, which emerge and are managed in social networking sites (Candón-Mena & Montero-Sánchez, 2021, p. 2925). Consequently, there is a substantial change in the structure of social movements, which, from cyberactivism, creates a new framework of technopolitical interpretation, determining the collective action of contemporary society.

In American slang, woke is a person “consciously and actively attentive to important facts and issues (especially issues of racial and social justice)” (p. 1052). According to Donohue-Dioh et al. (2021), the emergence of the woke movement is also a consequence of the failure of social action and education, fostering the creation of an “awakened vigilante” (p. 1046). As a collateral effect, a space is thus cemented in which identity politics is caught in a polarized and hypermediatized territory in those groups opposed to the ideas of “wokism”, whose greatest weapon is to generate moral panic with the tools of the society of the spectacle in which we live. In this way, we arrive at what Galán (2020) called “causecracy” (p. 276), giving this term two definitions: “Popular and informal suspension of people’s rights, generally freedom of expression and the presumption of innocence, in the name of a socio-political cause” and “a way of conceiving the world where political authority is considered to emanate from the social cause and which is exercised directly or indirectly by a quasi-religious power, such as a priestly caste”.

Causecracy, according to Galán (2020), can only occur in Western “customer-focused” societies, where online interpersonal relationships are the primary means of human communication. In these societies, the cause must always be emotional and depend on sentimental identification and fear, which is the emotionality of the cause “overflowing”. In addition, “believers” of the cause crowd around it: people who express their total adherence to the cause, share it in their networks, and actively participate in its boycotts and consequences. Thus, the result of this causecracy would be distrust towards experts since the value of these people does not depend on their professional background but the “consumer’s evaluation”.

The social groups most receptive to this type of audiovisual consumption are millennials and centennials. The television content of the series that millennials want to consume is usually characterized by the renunciation of old prejudices related to gender and race stereotypes, the more flexible and inclusive openness, the sense of brotherhood, community, and cooperation over one’s individualism, and, ultimately, the idea of social change (Fuenmayor & Aranguren, 2018). On the other hand, they are a generation that is very attached to technology, which easily encourages the consumption of streaming platforms. This has also forced many platforms and audiovisual companies not to promote hopeless or dystopian messages that displease audiences. Similarly, centennials reflect characteristics of millennials on social and political issues such as demographic race, ethnic diversity, the perception that racial and ethnic diversity is good for society, the belief that government should look out for the good of society, and political liberalism (Ross & Rouse, 2020).

2. Materials and method

The nature of this research is field-based, descriptive, and quantitative, as it seeks to determine the magnitude of the phenomena in a representative sample of audiences in Spain and Mexico through a national survey, whose questionnaire was previously validated by a panel of experts. About the scope, although we sought a sample size that would allow, through probabilistic procedures, to infer the responses to the total universe under study, it is no less accurate that some population sectors (social clusters) are less represented in the study. However, we sought a proportional allocation, which will be understood with an exploratory-correlational scope. Quantitative methods are characterized by data collection to test hypotheses based on numerical measurement and statistical analysis to establish behavior patterns and test theories (Hernández Sampieri et al., 2014). In exploratory research, basic data analysis is applied to identify the frequency of the phenomenon of interest and its general characteristics (Ramos Galarza, 2020).

2.1 Instrument

Once the instrument-questionnaire was designed and carried out after a theoretical construction of dimensions and indicators, it was subjected to expert judgment. The experts “are people whose specialization, professional, academic or research experience related to the research topic allows them to evaluate, in content and form, each of the items included in the tool” (Soriano Rodríguez, 2014, p. 25). The judgment was made in a single round using a Likert scale (1-5) with 10 experts, resulting in an arithmetic mean () of 3.47.

The final instrument included seven independent variables and three dependent variables referring to efficacy. The instrument was applied from April 26 to June 16, 2022, with 1025 responses from respondents through Google Forms in Mexico (mostly residents of large urban centers: Mexico City, Guadalajara, and Monterrey) and in Spain (Madrid, Barcelona, Seville, and Huelva). The questions that respond to the study’s dependent variables were structured on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree):

Should complaining on social networks be used to change what the audience considers un-

fair in an audiovisual production (e.g., the treatment of a minority group)?

Social networks should be used so audiovisual studios can listen to the audience, considering their opinion as consumers.

Opinions in social networks should not imply that an audiovisual producer should change the script of a film since each individual has his or her own opinion, and changing a plot or certain parts of an audiovisual work would be an act of censorship.

2.2 Sample

The reasons that led us to focus the study on millennials and centennials in Spain and Mexico were the following: First, according to a FINDER survey (Laicock, 2021), Spain and Mexico are the two Spanish-speaking countries where more streaming platforms are consumed in their respective continents. For this research, the generational age classification of millennials (born between 1981 and 1996) and centennials (born between 1997 and 2012), explained by Dimock (2019), will be used.

When the survey was conducted in 2022, the millennial generation was composed of people between 26 and 41 years of age, while centennials are those between 18 and 41 years of age

-also for 2022 (minors have been omitted on the recommendation of the university’s ethics committee). The age ranges used to divide centennials were, on the one hand, 18 to 21 (younger centennials) and 22 to 25 (older centennials). On the other hand, in the case of millennials, the age ranges were 26 to 34 (younger millennials) and 35 to 41 (older millennials).

In fact, in the list of countries worldwide that determined the percentage of the population with at least one streaming service at home by 2021, Spain was in 7th place with 57.67% and Mexico in 10th place with 56.01%. Therefore, Spain and Mexico are among the top ten countries where most streaming is consumed worldwide, specifically, the only two Spanish- speaking countries in the top ten ranking. In both countries, the most consumed platform is Netflix, being in Spain the most watched in 2021 with 33.8% of the share (Barlovento, 2021) and in Mexico with 89% by 2020 (Chevalier Naranjo, 2020). In addition, Netflix is expected to continue to lead the sector in Mexico by 2026 (Statista Research Department, 2021).

Regarding OTT consumption in Spain and Mexico by millennial and centennial audiences, the following characteristics can be summarized: On the one hand, in Spain, millennials and centennials exceed, in age groups ranging from 18 to 44 years old, 88% of the consumption of streaming platforms (Barlovento, 2021). On the other hand, in Mexico, 53% of millennials seek entertainment as their main content preference, 78% pay Netflix as their leading OTT, 93% prefer movies, 88% series, and they are the group that consumes the most significant number of online video content (Barlovento, 2021; IAB, 2017).

For this study, simple random probability sampling was used to select units drawn from a homogeneous population of size (n) so that each sample has an equal chance of being chosen (Tamayo, 2001). Since the “target population” (millennials and centennials) in both countries is greater than 100,000 people, the calculation formula for infinite populations will be used to determine the number of people to be surveyed (Aguilar-Barojas, 2005). In this sense, we have taken into account a confidence margin of 95%, a margin of error of +/-5%, and the population estimates of millennials and centennials in Spain, totaling 13,180,957 people (INE, 2021) and in Mexico, representing 46,200,000 individuals (Inegi, 2020), obtaining in both cases a minimum sample of 345 people for each region. As shown in Table 1, the effective sample of the present study will be 998 people, 347 individuals from Mexico and 651 from Spain, with an age range between 18 and 41 years. In addition, since this is a random selection probability sample, all the elements have the same probability of being chosen, being the individuals who will be part of the sample selected randomly (Casal & Mateu, 2003).

Table 1 National political efficacy survey sample in Spain and Mexico

| Generation | Spain | Mexico |

|---|---|---|

| Male Millenials | 160 | 108 |

| Female Millenials | 139 | 172 |

| Total Millenials | 299 | 280 |

| Male Centennials | 100 | 27 |

| Female Centennials | 252 | 40 |

| Total Centennials | 352 | 67 |

The survey was distributed through social networks like Instagram, LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp. Specifically, it was shared on the researcher profiles of those who conducted the study, as well as by other fellow researchers, and above all, it was disseminated through groups specialized in cinema, communication, or television series. The survey clearly stated that you had to belong to the allowed age range and have Spanish and Mexican nationality.

3. Results

3.1 Complaining in social networks and changing audiovisual narratives

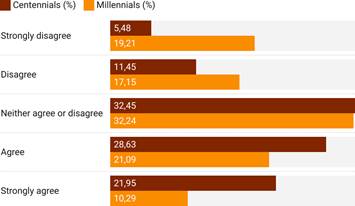

Centennials in Spain and Mexico generally feel higher political efficacy than millennials. That is to say, the younger ones believe more strongly that making claims through social networks can bring positive and effective results from the production company to which they are complaining. On the other hand, millennials, even though they are not far from centennials, do not agree so much with the idea that complaining on social networks can be a useful strategy to change those things that are considered unfair in an audiovisual production by the viewer (in this case, regarding the narrative treatment that they might find offensive, discriminatory or incorrect).

However, we found a practically identical percentage of undecided respondents on this issue in both countries. Moreover, the highest percentages of these results reflect that, for the most part, millennials and centennials in Spain and Mexico do not have a clear idea of whether they trust this approach via social networks to change the specific narrative of a film or series (Figure 1). Therefore, we conclude that there is greater internal political efficacy among centennials than among millennials, despite indecision prevailing in both cases.

Figure 1 Should complaining on social networks be used to change what the audience considers unfair in an audiovisual production (e.g., the treatment of a minority group)?

There is a statistically positive and significant correlation [R(1000)=0.238, p<0.001] between stating that complaining on social networks should serve to change those things they consider unfair in an audiovisual piece and stating that series and movies based on historical, biographical or true stories should show rigor, historical accuracy, and realism. This is understandable since, in both cases, more weight is given to external issues than to the creator’s will. In other words, there is a feeling shared by individuals of both generations towards the importance of reflecting reality before the will of the creators of an audiovisual work, which demonstrates the involved nature of millennials and centennials when consuming a film or series.

The one-factor Anova test indicates that there are significant differences among the four age groups [F(3, 998)=26.160, p<0.001], with the youngest (centennials) having the highest level of agreement with the idea that the complaint should serve to change what viewers consider unfair in the narrative treatment of something that bothers them (M=3.62; SD=1.076) than the millennials with the least (M=2.79; SD=1.267). Similarly, it is women who show greater agreement (M=3.52; SD=1.123) than men (M=2.56; DT=1.157), [t(996)=-13.001, p<0.001].

On the other hand, a significant and negative correlation [R(1000)=-0.105, p<0.01] was found between educational level and agreement with the statement, which means that the lower the educational level, the greater the consensus that social media criticism should be used to change the narrative of an audiovisual product. It is interesting to note that the degree of agreement with the statement is significantly and negatively correlated with the consumption of Amazon Prime Video [R(1000)=-0.096, p<0.01] and Filmin [R(1000)=-0.192, p<0.001]. There is a more significant agreement when these platforms are not consumed. The correlation is not significant with the consumption of Netflix, HBO, Disney+, or other platforms. That is, it cannot be said that there is an affirmative opinion on the issue of opinion on social networks about a plot on any platform, but it can be said that Filmin and Amazon Prime Video viewers do not have a high feeling of political efficacy in terms of the idea of complaining in social networks.

In addition, the degree of agreement with the statement correlates significantly and positively with consumption motivated by accompaniment [R(1000)=0.108, p<0.01] and negatively with consumption motivated by criticism [R(1000)=-0.117, p<0.001] and by art [R(1000)=-0.066, p<0.05]. However, the correlation with consumption motivated by leisure-fun or education is not significant. This means that the viewers most involved in complaining through social networks consume audiovisual content as an accompaniment (passively) while performing other tasks, and the least involved are those who intend to watch the series critically. Finally, the ideological spectrum and the country of residence have not shown significant differences among the participants.

3.2 Audiovisual producers must listen to the opinion of the audiences

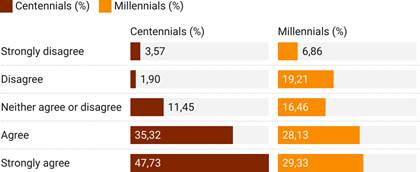

As a general rule, millennials and centennials in Spain and Mexico feel more effective in expressing their opinions on social networks concerning producers. Although, in both cases, the percentage of disagreement is lower, millennials are practically balanced in terms of acceptance of the usefulness of expression on social networks, but it is the centennials show a certain positive concordance in terms of this usefulness (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Social networks should be used so audiovisual studios can listen to the audience, considering their opinion as consumers.

Similarities to the previous point are found in that, according to Student’s t-test, the ideological spectrum and country of residence do not show significant differences. Women continue to show higher agreement (M=4.13; SD=0.996) than men (M=3.38; SD=1.328), [t(677.334)=-9.611, p<0. 001] and there continues to be a significant and negative correlation [R(1000)=-0.114, p<0.001] between educational level and agreement with the statement “ Social networks should be used so that audiovisual studios can listen to the audience, taking into account their opinion as consumers”, that is, there is greater agreement the lower the educational level. Likewise, the results are repeated in terms of generation, with young people showing the highest agreement (M=4.31; SD=0.822) and older people showing the lowest agreement (M=3.54; DT=1.299).

Similarly, although it may be a contradiction, there is a statistically positive and significant correlation [R(1000)=0.270, p<0.001] between stating that social networks should be used so that audiovisual production companies can listen to the audience and take their opinions into account and stating that series and films based on historical, biographical or true stories must show rigor and historical accuracy and realism. Regarding OTT consumption, a more specific difference has been detected: the degree of agreement with the statement that social networks should be used to allow audiovisual production companies to listen to viewers is significantly and positively correlated with the consumption of Netflix [R(1000)=0. 123, p<0.001] and HBO [R(1000)=0.96, p<0.01], while it does so negatively with the consumption of Amazon Prime Video [R(1000)=-0.072, p<0.01], Filmin [R(1000)=-0.164, p<0.001] and other platforms [R(1000)=-0.129, p<0.001]. The correlation is not significant with Disney+ consumption. Finally, the degree of agreement with the statement was found to correlate significantly and positively with consumption motivated by leisure-fun [R(1000)=0.172, p<0.001] and, again, by companionship [R(1000)=0.161, p<0.001]. While it is negatively correlated with consumption motivated by criticism [R(1000)=-0.151, p<0.001] and for art [R(1000)=-0.132, p<0.05].

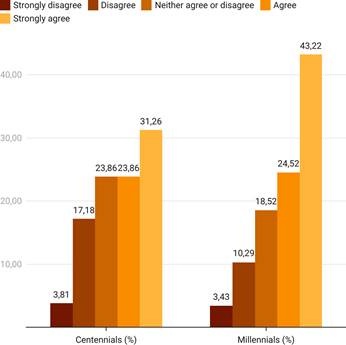

3.3 Opinión en redes sociales y censura a los creadores

In the responses to the statement, “Opinions in social networks should not imply that an audiovisual producer should change the script of a film, since each individual has his or her own opinion and changing a plot or certain parts of an audiovisual work would be an act of censorship”, we found a high positive consensus in both generations, but exceptionally high (43.22%) in millennials compared to 31.26% of centennials, who consider, for the most part, an act of censorship to creators the act of giving opinions against their plots. In other words, both generations are mostly against the censorship of filmmakers, although millennials are more likely than centennials to be against it (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Opinions in social networks should not imply that an audiovisual producer should change the script of a film since each individual has his or her own opinion, and changing a plot or certain parts of an audiovisual work would be an act of censorship.

Once again, there are no significant differences between Mexico and Spain according to Student’s t-test, nor in the ideological spectrum and, for the first time, in educational level. The opposite case is seen in the statement of this item, where younger people show less agreement (M=3.48; SD=1.225) and older people more (M=3.94; SD=1.185). The differences are again significant [F(3, 511.218)=8.431, p<0.001]. In other words, millennials seem to have a clearer idea of this issue than centennials, an aspect that may be logical, not only because of the age difference but also because of the difference in the educational stage.

Another difference with the two previous questions is that this time it is men who show a higher level of agreement (M=4.14; SD=1.139) than women (M=3.60; SD=1.147), [t(996)=7.254, p<0.001]. Regarding platform consumption, the degree of agreement with the statement is significantly and positively correlated with the consumption of HBO [R(1000)=0.88, p<0.01], Disney+ [R(1000)=0.100, p<0.01] and Filmin [R(1000)=0.125, p<0.001]. On the other hand, the correlation is not significant with the consumption of Netflix, Amazon Prime, and other platforms. Finally, the degree of agreement with the statement correlates significantly and positively with consumption motivated by criticism [R(1000)=0.068, p<0.05], by art [R(1000)=0.202, p<0.001], and by education [R(1000)=0.102, p<0.01], and negatively with consumption motivated by companionship [R(1000)=-0.088, p<0.01]. The correlation is not significant with consumption motivated by leisure-fun. In other words, the idea that the opinion of the spectators should be simply that and not expect a clientelist vision of the narratives as a symptom of censorship of the creators is more accepted by millennials than by centennials and, in the same way, by men than by women, by consumers of HBO, Disney + and Filmin versus other platforms and, finally, by those who consume streaming motivated by criticism, art or education, being those who consume narratives for accompaniment those who are less in agreement.

4. Discussion and conclusions

As a general rule, it has been found that centennials in both countries, without significant differences between the two nationalities, as well as in the ideological spectrum, feel more political efficacy than millennials when giving their opinion on social networks about the treatment that a film or series makes of something that makes them uncomfortable concerning social issues. That is, centennials seem to feel that their opinion is relevant to the change or modification of a plot, which would indicate a comparatively greater sense of self-efficacy or internal efficacy. In contrast, while not far from centennials in terms of political efficacy, millennials seem to agree markedly more than centennials that their personal opinion about a narrative should not go further than being an opinion.

In any case, in both generations, a character is involved with the world’s reality, coming to feel that the narrative must show reality, even above the creators’ will. In this way, the series that millennials wish to consume is usually highlighted by the renunciation of old prejudices related to stereotypes of any kind (race, gender, religion...), thus opening up the idea of social change (Fuenmayor & Aranguren, 2018, p. 65). Similarly, centennials reflect characteristics of millennials in social and political issues such as sexism or lack of diversity, showing both generations a spirit of awareness of justice in various ways (Ross & Rouse, 2020).

However, it is the youngest in the study - the centennials (18-25 years old) - who are more open to complaining on social networks, as well as those who show a higher level of agreement as a driver of change in streaming narratives than the millennials (25-41 years old), who seem to show less interest and more confusion in this regard. However, millennials are clearer about the idea that complaining on social networks can lead to censorship of the creators. It was also evident that women of both generations have a greater sense of efficacy than men, who tend to perceive complaining as an act of censorship more than their female peers. On the other hand, the lower the educational level, the greater the feeling of political efficacy they seem to have (except for the censorship issue, where the educational level does not seem to have a significant influence).

Regarding the platforms, it stands out that Filmin and Amazon Prime Video viewers feel less political efficacy when expressing their opinion on social networks about some political or social treatment of audiovisual production. However, Netflix and HBO viewers are more in agreement with the idea that claiming on social networks should result in a change on the part of producers or creators, being, once again, Filmin and Amazon Prime Video spectators those who disagree with this idea.

Moreover, HBO, Disney+, and Filmin viewers are more likely to agree that complaining on social media can be an act of censorship. In summary, it seems that as a general rule, Filmin and Amazon Prime viewers are the least interested in complaining about the treatment of a narrative in social networks, while Netflix and HBO viewers are the most in agreement, although HBO viewers seem to be wary of this idea because of the feeling of censorship they believe they can cause by making use of their social networks.

Regarding the use of the platforms, those who consume movies and series as an accompaniment mechanism (passively) while doing other activities tend to have a greater sense of political efficacy, in the same way as those who consume them for leisure or entertainment. However, millennial and centennial viewers who consume audiovisuals via streaming motivated by criticism, education, or art are generally more reluctant toward political efficacy and, in general, to the idea that complaining in networks can serve any purpose.

In conclusion, this study reveals several significant data: First, that centennials have a high level of political efficacy, and millennials moderately high, confirming that both generations feel a special interest in the ethical and realistic reflection of the world’s problems when consuming movies and series. Second, political ideology and nationality show no significant differences in this study’s perception of political efficacy. Third, gender and age seem more determinant in explaining political efficacy regarding streaming, complaints in social networks, and current consumption of series and movies. Thus, in a time so saturated with political correctness, we can glimpse how audiovisual fiction continues to be a space that creates and reflects the thinking of its audience. Recently, there have been «attacks» against classic films (e.g., Gone with the Wind and Fantasia), and, in addition, trust in politics and Western democracies is increasingly diminishing among the new generations.

Likewise, the birth of the Woke movement is also a consequence of the failure of social action and education, fostering the creation of an «awakened vigilante» (Donohue-Dioh et al., 2021, p. 1046-1047). It is not unreasonable to conclude that the political instability and the political, economic, and social crisis currently plaguing the West are calling the younger generations to believe in hope over freedom of expression. Movies and series show the reality of their time as they have always done, but audiences seem to be seeking confirmation of their political efficacy in the narratives they consume over the freedom of expression of their creators, leaving any uncomfortable or displeasing bias out of the question.

Understandably, individuals with a greater tendency to depression tend to perceive less external efficacy (Bernardi et al., 2022, pp. 23-25). Similarly, through the vast amount of content in citizens’ routines, individuals tend to feel “less responsive” to rulers and the political ecosystem (Bene, 2020). All this has led the marriage between technology and citizens to search in recent years for «safe spaces» with which citizens could defend themselves from political ineffectiveness. In short, it is not surprising that the term «Woke» has ended up cementing the foundations of digital culture that, under the pretense of freedom of expression and opinion, seems to encourage the legitimization of ideological and personal censorship of individuals that these groups consider “undesirable” (Muñoz-Rojas, 2021). Therefore, while the media saturate citizens with low levels of external efficacy, millennials, who, according to Fuenmayor & Aranguren (2018), prefer television content open to the idea of social change and ideas related to brotherhood and lack of individualism, show an openness to high external efficacy by consuming products in which safety, diversity, and ethics are the protagonists.

Consequently, «causecracy» thrives by offering «customer care» services to Western citizens who spend most of their time online (Galán, 2020), with younger citizens spending an average of 3.5 hours a day connected to their mobile devices, affecting their concentration (García- Ochoa, 2019) but undoubtedly reflecting that “interpersonal online relationships are the primary means of human communication” today (Galán, 2020). In this context, it could be said that millennials and centennials who consider it legitimate to complain on social networks about audiovisual content they dislike may be similar to a complaint in any store for a defective product, demanding a «refund».

Revolutionary social action movements have thus found cyberactivism a fruitful place for citizen protest or organization, which, once again, shows the evolution of new movements that emerge, self-organize and manage in networks. (Candón-Mena & Montero-Sánchez, 2021, p. 2925). Connectivity, in a hyperconnected world, affects how culture is consumed, such as movies and series, to the point of making collective thinking prevail over individual thinking, as well as the «cancellation» of people, ideas, or companies that represent contrary ideas, to the point of employing passion as the ultimate discursive weapon. For future research, it is suggested to obtain other samples from other Spanish-speaking countries and to analyze other feelings of a political nature, such as political alienation, cynicism, the third-person effect, or the spiral of silence. It would also be interesting to know the feelings of directors and screenwriters and to know if they feel pressured to self-censorship.