1. Introduction

The nonprofit Childmind Institute analyzes that socializing online tries to compensate everyone’s perfect look online by sharing pictures that make them look perfect (Ehmke, 2022). This fact is common in girls’ socialization and development of their identity, resulting in a higher vulnerability. The reason is that Snapchat, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram increased feelings of depression, anxiety, poor body image and loneliness among 14-24 year olds surveyed in the UK (Royal Society for Public Health and Young Health movement, 2017). Among youth in Spain the risk of suicide has grown by 2000% in 2022, and some of the behaviors related

-besides bullying, addictions, stress, and violenceare the unattainable aesthetic ideals presented by social networks (ANAR, 2023). The Federation of Associations for media quality in Spain, together with Safer Internet Center Spain 2.0 have published recommendations on responsible marketing regarding influencers who display a perfect body and project a self-centered image (IcMedia, 2021).

Coy & Garner (2010) highlight the marketing rationale that explains the impact of a more personal and accessible approach to brands and companies. Decisions in social sites look at brand endorsers who become lifestyle endorsers too. Brand ambassadors show a particular experience in a field of study that turns them into credible and closer references for people and communities. Users could be following both the most well-known and visible campaigns of the most important influencers’ aesthetics, as well as those against Instagram’s censorship.

Influencers are defined as “those people who are considered to have the potential to create engagement, drive conversation, and/or influence the decision to purchase products/services to a target audience” (IAB SpainInteractive Advertising Bureau-, 2022a: 5). Factors such as time and frequency of use, that “potentiate the especially undesired effects-perceived to be associated to a greater extent with younger people” according to the latest survey to 800 Spanish Internet users older than 15 (ONTSI, 2022). The digital report Spain 2022 concludes that 9 out of 10 people use social networks and spend almost 2 hours a day on them (We are social, 2022). Public prevention and regulation is recommended but only the media and the own network companies responsibility is perceived to avoid risks. What are the influencers’ roles?

The trend to focus the attention to the own body refers to the so-called self-sexualization (Kozee, Tylka, Augustus-Horvath & Denchik, 2007) and “interpersonal sexual objectification” (ISO), the act of reducing to body or body parts (Saéz, Valor Segura & Expósito, 2012, Rousseau & Eggermont, 2018). Self-sexualization is researched in adolescents’ performing sexualizing appearance behaviors and concluded that an appearance-focused attitude toward the self was a more important correlate of self-sexualization than an objectified perception of others” (Trekels& Eggermont, 2018). There are unique aspects of selfsexualization in social media, i.e peer norms and self-perception, compared to traditional media platforms that focus on self-sexualization through posting sexy pictures of themselves -sexy self-presentation (Van Oosten, 2016).

Since media advertisements, reality TV programs, advertising, music videosand social media portray women stereotypes based on body focus, sexual appeal risk behaviors have been associated with a sexualized aesthetic (Lynch, Tompkins, Van Driel & Fritz, 2016; Ward, Seabrook, Manago & Reed, 2016; McDade-Montez, Wallander & Cameron, 2017; Grower, Ward & Trekels, 2019; Condeza-Dall’Orso, Mattus & Vergara-Leighton, 2021; Glenn Cummins, Harrison Gong & Reichert, 2021; Mensa & Vargas-Bianchi, 2023).

Couto, Hust, Rodgers et al. (2022) suggest media literacy education may be beneficial for adolescents to recognize and question the gender stereotypic portrayals in music media after a research of stanzas of songs in the Hot 100 Billboard chart where the most common category was sexual content (n = 222, 28.4%), followed by degrading terms toward women (n = 71, 9%), and violence (n = 55, 7%). Other authors examine the presence of stereotypes on TV screenwriting (Rousseau & Eggermont, 2018) and videos (Aubrey, Hopper & Mbure, 2011) and link the portrayals with hate speech (Döring & Mohseni, 2019), hate towards partners (Cheeseborough, Overstreet & Ward, 2020; Sáez, Riemer, Brock & Gervais, 2022) and a form of discrimination (Miles-McLean, Liss, Erchull, Robertson, Hagerman, Gnoleba & Papp, 2015; Vance, Sutter, Perrin & Heesacker, 2015). The social influcence attached is shown in a study with 496 U.S. college women 18-37 years-old who reported “body surveillance, which in turn was related to more body shame, greater appearance anxiety, more rape precautions, greater safety concerns, and more fear of men” (Szymanski, Strauss Swanson & Carretta, 2021).

The following research questions guided this study:

What self-objectification categories are choosing the top influencers in Spain, men and women?

How frequently are self-objectification categories present in top influencers in Spain, men and women?

Does self-objectification in top influencers in Spain vary by sex, profession -exclusively influencers or other jobsand age?

The main objective of this research is to analyze the presence of self-objectification within the top influencers in Spain, men, and women and to identify the social values linked to self-objectification, whether it is success, social recognition and popularity or gender stereotypes.

2. Conceptual framework

2.1 Self-sexualization and self-objectification

Sexualization has been identified as an aspect that youth, especially females, use in communicating their identity related to physical appearance, gestures and stages and perceived as a whole.

Nowadays models and advertisers have questioned the focus on sexual attributes over the whole value of the person, and that would explain for example the decay of Victoria Secret as a sexualizing brand. Just over 15 years ago studies in Australia, US, UK and Spain agreed to highlight a sexual aesthetic also imposed on girls. The fact that sex sells would have found limits in the children’s rights to develop but also in the women’s right to be considered beyond their physical attractiveness. Numerous testimonials from professional models in videos and books show how difficult it is for them not to focus their self-esteem on their appearance, and the insecurity that results as a consequence of focusing on their physical appearance.

Gooding, Van Denburg, Murnen et al. (2011) examined the frequency and nature of sexualizing clothing available for girl children (generally sizes 6-14) on the websites of 15 popular stores in the US analyzing the following categories of the items: revealing -absence of clothing (via neckline or length), tightness, a sexualized body part -chest, waist, buttocks, and legs e.g. triangular pieces of fabric bikini swimsuitsand a writing on it with sexualizing content -a top that said “juicy” across the chest or a pair of underwear with ‘who needs credit cards’-, clothing items characteristics associated with sexiness -slinky lingerie-like material leopard or zebra print-.

Hall, West & McIntyre (2012) investigated the sexual material in visual media based on depictions of women in advertisements. Llovet Rodríguez, Díaz Bustamante Ventisca & Patiño Alves (2016) applied the content analysis of children’s commercial pages in fashion magazines in Spain adding to the validated scales of sexualization in the US the new features considered sexualising for kids in Spain: make-up, hairstyles, accessories and the posture or gestures. Speno & Audrey (2018) later confirmed in the U.S the same items of adultification and sexualization for 540 advertising and editorial images from women’s, men’s, and teen girls.

By building upon previous researchers’ approaches, self-sexualization of females in the XXI century is defined as “the voluntary imposition of sexualization to the self ” (Choi & Delong (2019: 1351). (1) The first condition of self-sexualization is favoring sexual self-objectification.

(2) The second condition is relating sexual desirability to self-esteem. (3) The third condition is equating physical attractiveness with being sexy. (4) The last condition is contextualizing sexual boundaries. According to these authors, one of the primary results of self-objectification is constant body monitoring, in other words, self-surveillance.

Appearance-related contingencies of self-worth and body surveillance were independently and positively associated with self-sexualization in a study that combined a qualitative analysis of Ten Facebook profile photographs of 98 young adult women from 18 to 28 years old and a self-report survey considering other variables such internalization of sociocultural beauty norms.

In Spain first Lozano Fernández, Valor Segura, Sáez Díaz & Expósito Jiménez (2015) and later Moya-Garófano, Megías, Rodríguez-Bailón & Moya (2017) adapted the interpersonal objectification scale to different target groups and confirmed the validation in several dimensions. From a questionnaire to 771 women from the general population Lozano et al. (2015) showed correlations with body evaluation, unwanted explicit sexual advances, benevolent sexism, state anxiety and self-esteem. Their contribution could be extended to emotions associated with body evaluation and sampling of the adolescent or even underage population, in order to prevent the impact of sexual objectification on psychological, interpersonal and social problems. Moreover, through two studies of 218 and 201 female undergraduate students Moya Garófano et al. (2017) also confirmed three dimensions of self-objectification -body surveillance, body shame and appearance control beliefs in womenand reported on their emotions after being exposed to an objectifying scenario: self-esteem, other-directedness, hostile sexism, and enjoyment of sexualization.

2.2 Self-sexualization as a mediator for financial gain, stereotypes, and poor mental wellbeing

Johnson & Yu (2021) published a recent systematic review from 2007 to 2020 on self-sexualization research, concluding that 31 papers operationalize the term with exposure to media and social media, self-objectification, internalization of sexualization, desiring attention from others and empowerment in a negative sense. The authors continue Grower et al., (2019) intuition that not only media but also women’s tendency to self-sexualize influences selfsexualization. In fact, they concluded that media use was indirectly related to self-sexualization through internalization of the thin ideal and the view of women as sexual objects.

Self-sexualization has been identified as a mediator for several effects: financial gain, stereotypes, and poor mental wellbeing.

“Visual stimuli may be more memorable than the written word because they are encoded and more easily retrievable in memory” (Glenn Cummins, Harrison Gong & Reichert, 2021: 709). Given the popular culture’s devotion to visual media, the socialization process may be influenced strongly by exposure to visual materials. In particular, young people are exposed to visual media that contain sexual material that may ultimately affect their understanding of sexuality (Cowan, 2012). For that reason Plieger, Groote, Hensky, Hurtenbach, Sahler, Thönes & Reuter (2022) investigated the perception of 916 participants who rated 28 Instagram screenshots on three dimensions, sexually revealing, appropriate, and attractive.In choosing the photos, the authors take into account not only the dimensions of the sexy clothes for example, scantily clad but also the posing behavior for example, legs open following the line of research on sexualization as a sum of factors. Their findings show altered perceptions of sexy pictures, selfsexualisation and enjoyment for example, they mention comments such as “it is important to me that men are attracted to me” and “I feel empowered when I look beautiful”. However, environment and gaze are two sexualizing dimensions that are not assessed as suggested by Llovet et al., (2016) and Narros et al., (2020) after observing sexualization in fashion magazines, editorials and advertising.

Regarding this aspect, two studies point out the effects of self-sexualization as a mediating role for gaining agency (Grower & Ward, 2021) or autonomy (Davis & Edwards, 2021). The first one is circumscribed to participants with sexual intercourse, when sexual agency involves other components and self-sexualisation can occur without sexual intercourse. The second study is an essay based on the recognition of female athletes’ agency. ‘Autonomy’ could be either a way of overcoming societal pressure on one’s character through a critical awareness of sociocultural norms, or the representation of parodic hypersexualisations of less articulate and less self-conscious girls. An empirical investigation through neuroscience could identify which of these explanations predominates in a given audience that represents itself as sexualised on social networks.

Creating their own content for social sites like Tik Tok young people turn semi-naked selfies and sexting1- into a way to obtain success (Mascheroni, Vincent & Jiménez, 2015; Kim, Bay-Cheng & Ginn, 2022; Mensa & Vargas-Bianchi, 2023), social recognition -selfies that self-sexualize likes(Bell, Casarly & Dunbar, 2018). Although selfies may be more strategic, they imply less authentic self-presentation on social media (Chen, VanTilburg & Leman, 2022). Sexual commodification also comes from peer pressure (Moreno-Barreneche, 2021).

Bell et al., (2018) analyzed 86 adult women from the UK and found that almost 30% of their images on Instagram were objectified, self-images and trait self-objectification gained more likes and the most frequent form of self-objectification was sexually suggestive poses. The limitations of their study are based on the sample, recruited through social media advertisements and on a university campus, which narrows the study to those most aware of the issue and to undergraduate students, respectively. Interestingly though Ramsey & Horan (2018) showed how from 1060 photos in Facebook and mainly Instagram of 61 undergraduate, sexualized photos gathered more likes on Instagram, generally among women, posting self-sexualizing photos was associated with more friends/followers and not with actual sexual agency in offline encounters. Their work distinguishes the amount of sexualisation which is low compared to previous studies with the ability to generate recall and conversation in an audience that ends up overestimating it. This is a deeper implication than what they conclude about young women’s need for attention.

A real-time behavioral study conducted by Chen, Van Tilburg & Lenan (2022) with female Tinder and Facebook users confirmed a positive association between trait self-objectification and strategic self-presentation, suggesting a heightened approval motivation among those who self-objectify. The authors also study mediations of approval motivation with authentic self-presentation, which seems a contradiction in terms if we understand the authenticity as showing yourself as you are, without fear of being judged by others.

Nothing new if we go back to the mid-1860s. “The act of undressing onstage soon became an inherent potential of every performance in which women were posed, arranged, featured, or displayed”, according to Foley (2005: 13-35). In popular entertainment forms, from theatrical ‘burlesque artists /exotic dancers of striptease to beauty pageant contestants, women “project a normal femininity and adhere to a strict hierarchy” (141-165). Despite the different image and rhetoric of displaying swimsuit bathing beauties or feather-waving burlesque, the author states that both represent opposite female stereotypes and leads us to think about it. In the age of social networks, what does the exhibition of femininity, carried out by the new interpreters of self-sexualization, imply?

Self-sexualization has also been related to stereotypes.

Davies (2018) observed how 600 Instagram posts of college accounts perpetuate gender inequalities by posting pictures of women’s bodies with no identity linked to alcohol, gifts, mottos and sayings. Among the limitations the author mentions is a need to conduct interviews and focus groups, and we find further research could explore a reflection on the way personality is represented in images.

From a netnographic approach at Facebook and Twitter, Kavanagh, Litchfield& Osborne (2019: 552) found that the top 5 women Wimbledon Tennis Championships players were exposed to sexualization that focused on the female physical appearance, sexualization that expressed desire and/or proposed physical or sexual contact, and sexualization that was vile, explicit, and threateningly violent in a sexual or misogynistic manner”.

From a broadcast daily on Chile’s main free-to-air television news programs a study concluded that thirty-six percent of the news items on children and adolescents stereotypes (Condeza Dall’Orso, Galo Erazo, Pérez Picado, Moreno Mella & Lavín España, 2022). An online survey found more than 400 Black American men associated greater objectifying behaviors and greater endorsement of the Jezebel stereotype with greater justification of violence toward women. At the same time, justification of violence was highest for another 400 Black women who endorsed the Jezebel stereotype and had more frequent experiences of sexual objectification” (Cheeseborough et al., 2020). In the analysis of profile photographs at MySpace.com, Hall, West & McIntyre (2012) also found an acceptance of constrained and stereotypical notions regarding both gender and sex roles.

Other authors highlight the addictions, depression, violence and misrepresentation related to self-sexualization (Aubrey et al., 2011; Miles-McLean et al., 2015; Davis, 2018; Gervais, Davidson, Styck, Canivez & DiLillo, 2018; Baildon, Eagan, Christ, Lorenz, Stoltenberg & Gervais, 2021; Cheeseborough et al, 2020). Selfies posted by peers, compared to models, and selfies perceived as edited, were judged more unfavorably (less intelligent, less honest) by 360 young adult female viewers participants of a study about Instagram by Vendemia & De Andrea (2018). The authors contribute to extending the investigation of the objectifying images of celebrity women to ordinary women by taking on the beauty ideals of being thin and sexualized as their own. Social networks democratize the use of photo editing tools and demonize their peers when they use them. It would be useful to replicate this study on the thin ideal now that the curvy trend is more widespread among celebrities and brands, and contrast the influence of internalizing this standard. In addition, a cultural cross-cultural analysis would be valuable to assess the weight of these canons in different cultures or the uniformity of a globalized society.

The problem of the internalization of cultural standards of beauty is its correlation with anxiety, stress for women and for men, social withdrawal, and positive relationships (Terán, Jiao & Aubrey, 2021). In two studies among 75 and 316 Italian women under 35 years old and highly educated using Instagram and Tik Tok respectively, the investigators conclude that “exposure to sexualized beauty ideals reduced body satisfaction and positive mood” (Di Michele, Guizzo, Canale, Fasoli, Carotta, Pollini & Cadinu, 2023). They contribute to a discussion on the different impact of sexualisation depending on the type of content women are exposed to, although the questionnaire could be enriched with a qualitative methodology focusing on the whys. In the same line,“the internalization of sexual ideals has also been related to poor mental well-being, Facebook use was also directly associated with poor mental well-being” (De Lenne, Vanderbosch, Eggermont, Karsay & Trekels, 2020: 52). Sexual objectification moderates the link between body weight contingent self-worth and depression (Szymanski & Feltman, 2015; Ching, Hu & Chen, 2021).

Baildon, Eagan, Christ, Lorenz, Stoltenberg & Gervais (2021: 190) found in 500 college women US that “the link between sexual objectification and drinking frequency was mediated by self-objectification, enjoyment of sexualization, and drinking for enhancement, social and conformity motives, and by self-objectification, body shame, and the conformity motive”.

2.3 Differences by sex towards self-sexualization

One interesting thing from the review is the differences by sex not only in perceptions towards others’ sexualization but also in effects related to self-sexualization.

McDade-Montez et al. (2017) concluded from the ten most popular children’s TV series popular among U.S. Latina and White girls aged 6 to 11 that sexualization was present within every coded episode, at least three instances present per episode. And more importantly, female characters were more commonly portrayed in a sexualized manner than male. In this sense, Lynch et al. (2016) investigated how games depict female characters more often in secondary roles, a sexualized approach linked to their physical capability and male-oriented genres (e.g. fighting).

Rousseau & Eggermont (2018: 71) concluded how one in five scenes in 465 scenes at five popular TV shows popular among Flemish preteens contained sexual behavior, and one in ten contained sexual objectification of men and women, these “more often judged for their appearance, but also more often shown treating others as objects in a non-sexual way”. In Spain, Narros González, Llovet Rodríguez & Díaz Bustamante Ventisca (2020) also concluded a significant difference among the perceptions of 449 men and women towards sexualized children outfits published in fashion magazines. Men perceived a lower number of sexualizing attributes and associated with body display while women more sensitive to the construct analyzed and to the characteristics tested.

Women experienced more sexual objectification in their interpersonal relationships while for men, self-esteem and power were the values associated with selfsexualization and mediated by enjoyment of sexualization. However, in women, benevolent sexism predicted the perception of interpersonal sexual objectification, and this effect was mediated by enjoyment of sexualization (Sáez et al., 2012). In a more recent study, the differences persist. For women, self-objectification, appearance anxiety, and stress serially mediated the associations between interpersonal sexual objectification and all relationship competencies. For men, self-objectification and appearance anxiety serially mediated the associations between ISO and relationship initiation and social withdrawal whereas self-objectification and stress serially mediated the associations between ISO and social withdrawal and positive relationships (Terán et al., 2021).

2.4 Influencers, Milllenials and self-sexualization

Millennials and generation Z are called ‘the influencers’ due to the million followers, especially girls, to buy or do what celebrities such as Kardashian or Paris Hilton did. Selfies of smiling and looking pretty captions were primary mediators of their reality shows success depicting food, beauty/fashion, travel. But also, ordinary people have got to attract attention on social media due to social activism (Dotson & Ashlock, 2023).

At a cognitive level, the children interviewed in Spain recognize influencers as an advertising phenomenon,“identify the sales intent and persuasive tactics that influencers resort to promote certain brands and try to exploit aspirational sentiments” (Zozaya Durazo, Feijoo Fernández & Sádaba Chalezquer, 2022: 315).

As brands invest on the social platforms used by influencers, IAB Spain developed a White paper on responsible influencers marketing. The world’s largest association of communication, advertising and digital defines“influencer marketing as a relatively new and booming business model whose ecosystem around is complex, misunderstood by many and in need of a series of guidelines to shed light on how it works” (IAB Spain, 2022a: 15).

Feijoo, López-Martínez & Núñez-Gómez (2022) identified body and diet as persuasive arguments in influencer marketing in a study based on 12 focus groups with minors aged 11-17 years of age who reside in Spain. The authors concluded that “minors primarily receive commercial messages about physical appearance -such as makeup or clothingand “the construction of a perfect, aspirational world, which minors absorb and accept as part of the digital environment and end up incorporating into their behavior on social networks” (Feijoo et al, 2022: 2). The methodological value of this research lies in the use of a qualitative approach with the children themselves, from whom a survey could not reveal important information and who are not usually accessed due to permission issues with minors.

According to Choi (2017), the trend of self-sexualization starts with a stage celebrityled stylized pornographic sexual imagery/sexiness (edited by a fashion stylized magazine, editor and photographer): celebrities mimic pornographic sexuality since the 1990’s and porn stars write bestselling books were giving advice on sex life for lifestyle magazines. ‘Selfsexualization performance’ includes “practicing sexy behaviors such as mimicking sexual behaviors from pornography, sending nude pictures of oneself to others, posting a sexualized picture of self on the Internet, and participating in boudoir or pinup photography (i.e., highly sexualized photography taken in a studio by professionals)” (Choi, 2017: 30). Then, there is a normalization of a striptease culture: the general public supports and creates a sexual selfexhibition and bodily exposure and introduced it as “a subset of a broader sexualization of mainstream culture”; boudoir photography or pinups, flash their breasts at public events, and manage their appearance to feature mainstream pornography wearing low cut cleavagerevealing tops, crop-tops that emphasize midriffs, or tops with exposed backs that enable exposure of undergarments if worn, t-shirts emblazoned with phrases such as ‘up for it’ and pants labeled ‘juicy’ or ‘delicious’ across their buttocks, nude self-portrait or naked torso (Choi, 2017: 4-5).

3. Methodology

Previous studies conducted in self-sexualization are either perception or content analysis, so we decided to start with a content analysis of photos posted by Spanish influencers on Instagram. We also follow the recent recommendation to address self-objectification interventions targeting men as there is a lack of empirical research compared to women’ s (Pecini, Guizzo, Bonache, Borges-Castells, Morera & Vaes, 2023).

The criteria for selecting the sample is based on the findings of two Spanish reports on influencers in Spain: iCmedia (2021) and IAB Spain & Nielsen (2022). The sample is broad so as not to bias those influencers who show a sexy or perfect body and project an egocentric image, the sample is extended to the top influencers (boys and girls) of young Spaniards. In order to answer the research question “Do you dress to succeed?” we want to know to what extent this occurs and, if so, under what circumstances (profession, gender, age). The sample is also broad because it is not limited to lifestyle influencers, fashion influencers (for example this ranking) or influencers from a social network such as Instagram. The interest of this sample is that it covers all influencers of young people in Spain, regardless of the importance they give to their body appearance, which could be more related to self-objectification.

In order to choose the influencers analyzed for this research, we have consulted a Spanish digital news media focused on the economic, business and technological world called Merca2. es (2022) which publishes every year from 2018 the Study of the 500 Most Influential Spaniards in Marqués de Oliva Foundation. We have used this report because it is used by both marketing and PR practitioners and scholars to detect which Spanish people are the more influential in Spain every year.

The last ranking published by this media was published in 2022 but the research process was conducted between November and December 2021. The result of this work was the publication of a list of 500 influential people. For this research, we have chosen the first seven women and men presented in that ranking (see table 1). Other influencer rankings include all types of influencers, not just those who focus on physical exposure.

Table 1 Influencers analyzed sorted by sex category

| Men | Women |

|---|---|

| Ibai Llanos | María Pombo |

| Ignacio Gil Conesa (Nachter) | Ester Expósito |

| Risto Mejide | Sida Doménech (Dulceida) |

| Álex Domenech | Paula Gonu |

| Marc Forné | Alexandra Pereira |

| Pau Clavero | Giorgina Rodríguez |

| Pablo Castellano | Laura Escanes |

Source: own elaboration based on the Study of the 500 Most Influential Spaniards in Marqués de Oliva Foundation (Merca2.es, 2022)

According to Kantar media (2022), the most popular advertising environments in Spain are Tik Tok, Instagram and Twitter, being Tik Tok, the global leader since 2021. The latest data from IAB Spain (2022b) conducted among 1,043 female and male users from 12 to 70 years of age and 212 surveys of digital industry professionals, reported that the fastest growing and most used networks are WhatsApp -remains the social network with the most users-, Facebook, Instagram -(which is growing vs. 2021 (64%) and 2020 (59%) followed by YouTube and Twitter. We have chosen Instagram as “of the 10.5 million active influencers on Instagram, TikTok and YouTube in Europe, 15% are Spanish, with Instagram standing out as the platform with the largest number of users (IAB & Nielsen, 2022). Instagram is also used by all the top influencers from the list.

The codification process was realized with a qualitative deductive paradigm. We have coded the Spanish influencers’ photos according to the coding from the academic literature review (see table 2). In this table, we have compiled the nomenclature used by different researchers to name the three main categories related to the role of influencers and the sexualization of their public image. The subcategories relating to each of these three major categories are also listed.

Table 2 Description of self-objectification categories according literature review

| Categories | Subcategories description |

|---|---|

| Self-sexualization | Voluntary imposition of sexualization to oneself (Van Oosten, 2018) |

| Internalization of the imposed obligations from the outside (De Lenne et al., 2020; Terán et al., 2021) | |

| Treat or experience oneself as a sexual subject with a favorable attitude. | |

| Place greater emphasis on sexual attraction (Choi & Delong, 2019), body satisfaction and positive mood (Di Michele et al., 2023) | |

| Sexy self-presentation (Van Oosten, 2018) | |

| Sexually alluring behavior (Aubrey & Frisby, 2011) | |

| Sexualizing appearance behaviors (Trekels & Eggermont, 2018) | |

| Enjoyment of sexualization (Moya-Garófano et al, 2017, Baildon et al., 2021; Plieger et al., 2022) | |

| Reducing to body or body parts (Saéz et al., 2012) | |

| Self-centered image | Appearance-focused attitude toward the self perfect body (Trekels & Eggermont, 2018) |

| Posting objectified self-imagesselfies (Bell et al., 2018) | |

| Strategic self-presentation (Chen et al., 2022) | |

| Stricter appearance standards (Aubrey & Frisby, 2011), body weight, place importance on physical attractiveness (e.g., symmetrical features) (Choi & Delong, 2019) | |

| Self-objectification: more often judged for their appearance (Rousseau et al, 2018) | |

| Social influence | Social power and popularity (Choi & Delong, 2019) |

| Selfies that self-sexualize likeshigher frequency of posting objectified self-images was associated with trait self-objectification and receiving more likes on this type of self-image (Bell, Casarly & Dunbar, 2018) | |

| Success (Mascheroni, Vincent & Jiménez, 2015; Kim, Bay-Cheng & Ginn, 2022; Mensa & Vargas-Bianchi, 2023), | |

| Social recognition (Ramsey & Horan, 2018; Bell, Casarly & Dunbar, 2018). | |

| Popularity gained primarily due to amateur pornographic videos -by female celebrities such as Paris Hilton, Kim Kardashianor large breast implants -Pamela Anderson(Choi & Delon, 2019). | |

| Sales growth based on a magazine cover of Demi Moore naked; a book titled Sex by Madonna; the music video Justify My Love and the album Erotica (Choi & Delon, 2019). | |

| Empowerment (negative sense) (Johnson & Yu, 2021) |

Source: own source

According this three main categories, discussed by the two co-authors in different work sessions, be have started the photos codification process. In particular, a deductive coding process with QSR Nvivo was applied (Fereday & Muir-Crochaine, 2006; Kalpokas, & Radivojevic, 2022).

As in previous research work at the methodological level, we have used the QSR Nvivo software to carry out the analysis through the condensation of the meanings and the identification of categories according to the theoretical framework of the paper and the research objectives previously defined (Pedrero-Esteban, Pérez-Escoda & Establés, 2021). More specifically, like in previous works, the researchers analyzed the Instagram photos and classified them into the different categories to maximize neutrality in the treatment of all the photos during the codification process, to promote the objectivity and validity of the results. “To guarantee the reliability of the coders, the analysis criteria were agreed upon through meetings and work sessions, and the coding performed by each of the researchers were reviewed and adjusted according to the operational definitions of each category” (Pedrero-Esteban, Pérez-Escoda & Establés, 2021: 4). For that reason, the codification process was made by the two co-authors and the coding was compared in order to validate the results obtained (a 95% of similarities between the two codifications).

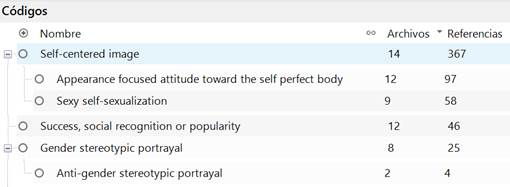

Although the researchers initially proceeded with a deductive analysis of the photos based on previously reviewed scientific literature, further subcategories emerged inductively during the coding process such as anti-gender stereotypic portrayal. This practice is very common when coding qualitative data with software such as QSR Nvivo. The following figure shows the final coding of the analyzed photos (figure 1).

Figure 1. QSR Nvivo code tree emerged during the codification process

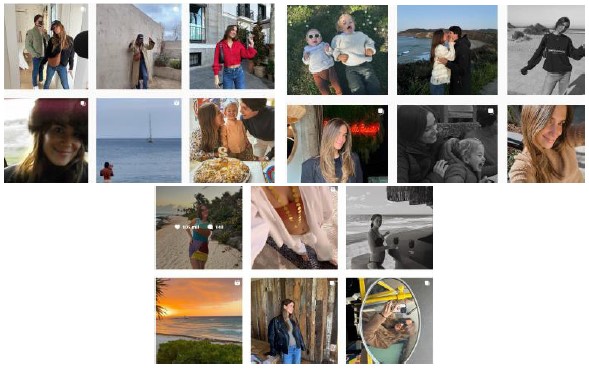

As we have discussed before, 14 Spanish influencers were selected for this study (7 men and 7 women). From 13 influencers we have selected 18 Instagram photos and for one influencer only 12 photos because she has not posted the same number of photos during the collecting process. In particular, the photo selection was realized in 2023 in three different days during the months of January (day 12), February (day 17) and March (day 3). The research team decided to choose one random day each month in order to collect all the photos that were posted by the influencers between these dates. Finally, it has collected and analyzed 246 Instagram photos.

4. Results

As we have mentioned before, the main objective of this research is to analyze the presence of self-objectification within the 14 top influencers in Spain, seven men and seven women, and to identify the social values linked to self-objectification, whether it is success, social recognition, popularity or gender stereotypes. In this sense, we can see in graphic 1 the coding of the analytical categories and the presence of each of them in the different photos shown by the selected influencers. Specifically, it can be noted that women tend to project a more sexualised image than men, both in terms of sexy self-sexualization and appearance focused attitude towards the self-perfect body. However, gender stereotypes are shown in a similar way in both men and women. On a more marginal level, it can be observed that some male influencers challenge these gender stereotypes, showing a subversive attitude by turning these roles on their head (wearing clothes traditionally associated with women, for example).

Going deeper into this idea, graphic 2 shows exactly how many male and female influencers appear in each analytical category. As expected, the self-centered image is present in all of them. It is striking that only in the aforementioned category, anti-gender stereotypic portrayal, and also in the category of success, social recognition or popularity, do male influencers have a greater presence than female influencers. Specifically in the case of the second category, a more in-depth analysis reveals why this is the case (see table 4).

In table 3, we present the results found in each category regarding the two variables (influencers’ sex and age). Of the total of the 14 influencers who are the subject of this study, 9 of them (4 men and 5 women), 64.28% in total, are part of generation Z, with ages between 20 and 29 years old. On the other hand, a total of 4 of them (3 women and 1 man) belong to generation Y or Millennial, and their ages are between 30 and 39 years old, which represents 28.57%. Finally, only one male influencer belongs to generation X, aged between 45 and 49, which represents 7.15% of the total number of Spanish influencers in the study.

Table 3 Results found in each category regarding influencers’ age and sex

| Age | Gender stereotypic portrayal | Anti-gender stereotypic portrayal | Self-centered image | Appearance focused attitude toward the self perfect body | Sexy self-sexualization | Success. social recognition or popularity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25-29 years (8 influencers) | ||||||||

| Men (4 influencers) | 50% | 50% | 100% | 75% | 50% | 100% | ||

| Women (4 influencers) | 50% | 0% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||

| 30-34 years (3 influencers) | ||||||||

| Men (1 influencers) | 100% | 0% | 100% | 0% | 0% | 100% | ||

| Women (2 influencers) | 100% | 0% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 50% | ||

| 20-24 years (1 influencers) | ||||||||

| Men (0 influencers) | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | ||

| Women (1 influencers) | 100% | 0% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 0% | ||

| 35-39 years (1 influencers) | ||||||||

| Men (0 influencers) | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | ||

| Women (1 influencers) | 0% | 0% | 100% | 100% | 0% | 100% | ||

| 45-49 years (1 influencers) | ||||||||

| Men (1 influencers) | 0% | 0% | 100% | 100% | 0% | 100% | ||

| Women (0 influencers) | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | ||

| Global (14 influencers) | 57.14% | 14.29% | 100% | 85.71% | 64.29% | 85.71% | ||

Source: Own source

On the other hand, table 4 shows the results obtained taking into account the variables sex and profession with the analytical categories of the study. The results are presented in percentage terms. Likewise, Table 5 analyzes the data obtained taking into account the variables occupation and age with the aforementioned categories. On this occasion, the data are shown in absolute terms, showing the exact number of influencers appearing in each analytical category. Throughout this section of the article, in addition to the two initial graphs that have already been previously shown, we will also be breaking down the main results obtained in these three tables by referring to them.

Furthermore, table 3 shows the differences found in the publication of photos on Instagram not only by age group, but also by gender. In this regard, as we have highlighted above, the largest group is that belonging to generation Z, but it has been divided into two age groups, from 20 to 24 years old and from 25 to 29 years old. In the 20-24 age group, there is only one female influencer who has a clear tendency towards sexy self-sexualisation in her photos, as well as a focused appearance attitude towards the self perfect body and gender stereotypic portrayal. In this regard, it should be noted, as shown in table 4, that this woman’s profession is an actress, and therefore, the stereotype of self-objectification of the body for work-related reasons could be repeated.

Table 3 shows that in the second group of Generation Z influencers (aged 25 to 29), we find that both 50% of the men and 50% of the women show gender stereotypic portrayal in their photos, while in the case of one of the men, who is a model (see table 4), he challenges these stereotypes by using an anti-gender stereotypic portrayal perspective through images of his work that defy the gender stereotypes traditionally associated with men. In relation to the category of the appearance focused attitude towards the self-perfect body, in the case of the 4 women in this group, this form of self-representation appears in some of the photos, while in the case of the men, 3 of the 4 also self-represent themselves in this way. With regard to the category of sexy self-sexualization, it remains that 100% of the women in some of the photographs self-objectify themselves, while in the case of the men it is only 50%. Regarding the category of success, social recognition, or popularity, 100% of both men and women show a photograph that complies with this parameter.

Table 4 Results found in each category regarding influencers’ sex and job

| Job | Gender stereotypic portrayal | Anti-gender stereotypic portrayal | Self-centered image | Appearance focused attitude toward the self perfect body | Sexy self-sexualization | Success. social recognition or popularity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model & Influencer (3 people) | ||||||||

| Men (2) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||

| Women (1) | 0% | 0% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||

| Influencer (4) | ||||||||

| Men (0) | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | ||

| Women (4) | 75% | 0% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 75% | ||

| Actress (1) | ||||||||

| Men (0) | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | ||

| Women (1) | 100% | 0% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 0% | ||

| E-sports streamer & youtuber (1) | ||||||||

| Men (1) | 0% | 0% | 100% | 0% | 0% | 100% | ||

| Women (0) | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | ||

| Entrepeneur & influencer (2) | ||||||||

| Men (1) | 100% | 0% | 100% | 0% | 0% | 100% | ||

| Women (1) | 0% | 0% | 100% | 100% | 0% | 100% | ||

| Artist (1) | ||||||||

| Men (1) | 0% | 0% | 100% | 100% | 0% | 100% | ||

| Women (0) | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | ||

| Youtuber & influencer (1) | ||||||||

| Men (0) | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | ||

| Women (1) | 100% | 0% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||

| Producer, publicist and TV presenter (1) | ||||||||

| Men (1) | 0% | 0% | 100% | 100% | 0% | 100% | ||

| Women (0) | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | ||

| Global (14 influencers) | 57.14% | 14.29% | 100% | 85.71% | 64.29% | 85.71% | ||

Source: Own source

In the case of the Millennial generation, influencers have been divided into two age groups: 3034 and 35-39. In the case of the first group, there is a relationship between the male influencer who does not sexualize his body and is socially successful, and who has a self-described job as an entrepreneur and influencer (see table 5), while in the case of women, half of them also appear in the categories of sexy self-sexualization and appearance focused attitude towards the selfperfect body in order to be socially successful. With regard to the second group of millennials, there is only one woman, who also calls herself an entrepreneur and influencer (see table 5), but in contrast to the male influencer mentioned above (see table 4), in this case, photos of the category of appearance focused attitude towards the self-perfect body are present.

The last generation represented in this ranking of 14 most relevant influencers is generation X, with the case of a man between 45 and 49 years old. The data obtained show that he does not show sexualized photos of himself, but he does show the importance of the body and taste for fashion, as well as to show his social recognition he is photographed on multiple occasions at times when he is doing his job (see tables 3, 4 and 5). This is a sample of the importance of work in the male sphere to obtain success, social recognition, or popularity without having to use the self-sexualization of the body. Therefore, there is also a clear relationship between biological sex, the type of work performed and also being older (see tables 3, 4 and 5) when choosing what image these influencers want to project on Instagram.

Table 5. Results found in each category regarding influencers’ age and occupation

| Job | Gender stereotypic portrayal | Anti-gender stereotypic portrayal | Self-centered image | Appearance focused attitude toward the self perfect body | Sexy self-sexualization | Success. social recognition or popularity | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25-29 años (8 influencers) | ||||||||

| Model & influencer (3) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Influencer (2) | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Streamer e-sports & youtuber (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Artist (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Youtuber & influencer (3) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 30-34 años (3) | ||||||||

| Influencer (2) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Entrepeneur & influencer (1) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 20-24 años (1) | ||||||||

| Actress (1) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 35-39 años (1) | ||||||||

| Entrepeneur & influencer (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 45-49 años (1) | ||||||||

| Producer, TV presenter and advertiser (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Global (14 influencers) | 8 | 2 | 14 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 14 | |

Source: Own source

In total terms, table 4 shows that of the top 14 influencers in Spain in the sample, 100% show photos with selfies (self-centered image), although some sometimes show photos in which other people, places or things appear; more than 85% have photos with appearance focused attitude toward the self perfect body and also more than 85% of the influencers show that they have success, social recognition, or popularity. On the other hand, more than 64% show sexy selfsexualization attitudes and more than 57% show a gender stereotypic portrayal.

Finally, in global terms, Table 5 shows that there is a clear relationship with influencers, who are mostly men, who have jobs in which the importance of physical appearance is not the main focus, and the category of success, social recognition, or popularity. On the contrary, in most of the professions that are self-perceived as having an important physique (models or actors), there is a greater tendency to sexy self-sexualization and appearance focused attitude toward the self perfect body.

5. Discussion and conclusions

This investigation addresses a research need to better understand the process of selfobjectification and find ways to overcome its consequences, as highlighted by Pecini et al. (2023). The research also pretends to understand the blooming and complex ecosystem of influencers, a recommendation from IAB Spain (2022).

Our results have extended the global research on the unique aspects of the XXI century’s selfsexualization in media platforms: peer norms and self-perception considered by Van Ooosten (2016). Regarding peer norms, despite the normalization of selfies among successful influencers, selfies that come from peers are judged to be less favorable -less intelligent and honestthan the ones that come from models (Vendemia & De Andrea, 2018). This fact could be explained by the role of social withdrawal in the internalization of beauty standards as Terán et al. (2021) suggest. Regarding self-perception, socializing online has shown a particular role in projecting a self-centered image, one of the three main categories of self-objectification based on the literature review found in this research. The other two, self-sexualization and social influence, are also identified at the top 14 influencers on Instagram in Spain in 2022.

After the analysis of top influencers in Spain a self-objectification category has been added, anti gender stereotypical portrayal. The subcategories defined within the study combine extremes like appearance-focused and body perfection with reducing to body parts. The big contradiction seems to take as credible and successful references people who share perfect pictures (Ehmke, 2022) and self sexualization is linked with an altered perception of sexy photos (Plieger et al, 2022). The problem comes when pictures based on physical appearance constitute unattainable aesthetic ideals (ANAR, 2023) that youth cannot separate from constant body monitoring, shame, and hostile sexism.

Following the APA (2007) report on childhood sexualization, we found that Choi & Delong’s (2019) contribution is to describe the internalization of sexualization as a “voluntary imposition” at any age. Who would like to be subject to an obligation related to poor mental well-being (De Lenne et al., 2020, Ching et al, 2021)? The possible explanation for acting out of compulsion can only be understood in terms of the reward in social recognition that the self-presentation of sexual attractiveness obtains. Influencers who self objectify in this study through selfies are also amongst the most popular of the list, such as Bell et al. (2018) have shown; and influencers who self sexualize are mostly women, as Ramsey & Horan (2018) demonstrated. However, this interpretation contrasts with the definition of sexting as content of sexual nature created consciously and sent voluntarily by their protagonist to other people (Safe internet for kids, s.f.). What is the peculiar role of sexual agency in self-sexualising behavior? An entertainment spectacle such as beauty pageants, which exert social pressure on the strict femininity to which they conform (Foley, 2005)?

Comparing the two main categories analyzed within the self image of influencers, men and women, there is a profound similarity on the high level of self-centered image. As stated by Feijoo et al. (2022) the body is definitely a persuasive argument also for the influencers analyzed in this research. There are several attached behaviors to a self-centered image by the literature that have been confirmed. To begin with, constant body monitoring is one of its primary results of selfsexualization according to Choi & Delon (2019). Secondly, there is a correlation of selfsexualization with the appearance-focused attitude (Trekels & Eggermont, 2018). And finally, a less authentic self-presentation is assigned to the strategic selfies by Chen et al. (2022). This lack of human authenticity contrasts with the attitude valued by brands to demonstrate a real, solid and transparent commitment to gain consumers’ attention.

Regarding comparisons by sex, we found strong differences in the subcategories that most authors link to self-sexualization. Women are more represented in sexy self, self perfect body and gender stereotypical portrayal whereas men show more evidence based on success and anti gender stereotypical portrayal. These results confirm the differences found by sex toward sexualization highlighted by numerous studies. The reason that explains a cultural perpetuation of representations of women’ community standards would be no other than the acknowledgments of the time, that is, “the act of exposing flesh for financial gain: a commercial business transaction situates female bodies both as commodities for cultural consumption and as tools for the success of individual performers engaged in the business of display” (Foley, 2005: 111-139). Are we in the self-branding era where social media audiences view luxury with anticipation of intense pleasure, ameliorating ethical concerns, as suggested by Kozinets (2023)?

In relation to self-objectification by profession, the results call attention to the importance given by influencers to their appearance and perfect body whether their job is being an influencer or a model. In this sense, 76 models (87% female) reported their experiences on sexual objectification to protect them from pressures -45% reporting experiencing lack of privacy when changing and a few also sexual harassmentthrough new industry policies (Rodgers, Ziff, Lowy & Austin 2020). Why then do the model influencers analyzed choose for their social media profiles a body exhibition that professional models have renounced to go beyond their sexual attractiveness? In this sense, Kavanagh et al. (2019) denounced that social media was the scenario for genderbased violence against the professional tennis players as the traditional media never was. It is hard to believe that one can consciously aspire to the violent or misogynistic threat linked to the sexualisation to which the female tennis that these women were exposed.

Conclusions on age focus on the impact that most followed influencers might have on young people. Zozaya Durazo et al. (2022: 315) determined that “children are more receptive and trusting of recommendations from influencers close to their tastes, hobbies and preferences”. At the same time adolescents have shown a critical ability towards influencer marketing based on several aspects such as the coherence and affinity of the promoted product and the influencer, as well as the background or profession of the content creator”. Based on these recent results, why not extend the debate to aspects such as self-centered image and self-objectification, as well as the perpetuation of stereotypes and the focus of success to appearance? Why not consider the influencer as a personal brand in itself with enough potential to move a better world, like the good attention that social activism generates (Dotson & Ashlovk, 2023)?

A practical implication of this study is the proposal to the authors of the white papers on influencers of a responsibility index, classifying them according to the parameters it establishes for responsible marketing -use of stereotypes, unattainable aesthetic ideals, self-centered image, etc…-, as other sustainability indexes do. For instance, Haz Foundation publishes the index Commitment and Transparency. We believe that these indexes complement the existing ones, which only consider the reach of the company’s products and services.

It is clearly difficult for minors to distinguish between influencers’ attempts at persuasion (Zozaya et al, 2022) and risk being exposed to some of their content. Though social media is an important medium for millennials and generation Z’s daily lives to communicate and do social activism, they are perpetuating stereotypes of passive women focused on their pretty self (Dotzon & Ashlock, 2023). Relevant enough is to defend the rights of “seen as a person with the capacity for independent action and decision making” (Van Oosten, 2018: 187), an objective far from the fact that body evaluation is related to greater adherence to benevolent sexist beliefs (Plieger et al, 2022). Nor does it seem compatible with the protection of children from communications that promote the cult of the body and appeal to social rejection due to physical condition or success due to aesthetic factors, according to the Audiovisual Law in Spain (BOE, 2022). Considering this awareness, we might conclude a global problem from east to west: China, US, Latin America, Europe. Results from Chilean programs realize that today TV is still the most frequent media that presents negative stereotypes (Condeza Dall’Orso et al., 2022). We agree with the authors that one way of dealing with mental health issues could be to identify the stereotypes though they do not provide ways to do it.

As a responsible marketing influencer, further research could also be to examine the coherence of brands that emphasize social values and at the same time are sponsored by influencers who selfsexualize. Another study involving neuromarketing methodologies could measure several perceptions towards self-objectification and sexualized beauty ideals: peer mediation (Macheroni et al, 2015; Moreno-Barreneche, 2021); anxiety or stress, social withdrawal, positive relationships (Terán et al., 2021); body dissatisfaction and mood (Di Michele et al., 2023); poor mental wellbeing (Szymanski & Feltman, 2015; De Lenne et al., 2023); sexism or enjoyment (Moya-Garófano et al., 2017), sexism or self esteem (Lozano et al., 2015). In order to provide an in-depth study, we need to highlight the three years longitudinal analysis that concluded the moderating role of interpersonal sexual objectification in the links between body weight contingent self-worth and negative psychological outcomes (Ching et al, 2021).

Another future research is to investigate sexual objectification in cyborgs in Spain, as Renold & Ringrose (2016) showed in a study of boys and girls living in urban inner London and semirural Wales (UK) the importance that “the more-than-human is foregrounded and the blurry ontological divide between human (flesh) and machine (digital). It seems that likes on social media do not reflect positive feelings in offline encounters, such as Ramsey & Horan have suggested (2018).

Future lines of research also advise listening to young people about the power of influencers in generating values such as trust, popularity, and prestige (Frithjof, 2022). It would be interesting to assess if interpersonal self-objectification plays a role in mediating young people’s relationship competencies, such as in adults (Sáez et al, 2012). We wonder if young people who aspire to be influencers consider these same values important enough to build their own personal branding. Our proposal would consist of implementing a research action methodology with youth to identify stereotypes portrayed by their top influencers and search for ways to counterbalance, for instance, by highlighting personal aspects beyond their bodies. Another way of extending the sample is by studying the image of child influencers, taking for example the ranking of The 10 most successful child youtubers in Spain (Bastero, 2023) or Top 10 most influential children in social networks 2023 (Luduena, 2023). This information will also provide positive influencers such as the Top 15 educational influencers of 2022 (Influence4you, 2023). Finally, we would like to design a cross-cultural and transnational study of the possible self-sexualization of influencers in order to find out what differences and similarities there are with respect to the results obtained in this study (only with Spanish influencers) and with others from Spanish-speaking Latin American countries.