Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y Salud Publica

Print version ISSN 1726-4634

Rev. perú. med. exp. salud publica vol.37 no.4 Lima Oct-Dec 2020 Epub Nov 09, 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17843/rpmesp.2020.374.5838

Originales breves

Food and beverage supply and advertising in schools and their surroundings in Metropolitan Lima. An exploratory study

1 CRONICAS, Centro de Excelencia en Enfermedades Crónicas, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Perú.

INTRODUCTION

Over the last decades, the consumption of processed and ultra-processed products has increased in Latin America; these products are characterized by having higher energy density and high concentrations of sodium, fat and added sugars 1. Increased consumption of these type of food has contributed to the excess weight gain in children and adolescents that is observed throughout the region, including Peru 2 , 3.

Schools are essential spaces for feeding children and adolescents. Evidence from Europe, North America 4 , 5 and Latin America ( 6 , 7 ) shows an increase in the supply of ultra-processed foods in educational institutions and their surroundings, making them more accessible to children.

In 2013, the Peruvian government enacted the Law for the Promotion of Healthy Eating for Children and Adolescents (Law 30021) 8, which establishes the use of warnings labels on packages of beverages and processed and ultra-processed foods to indicate the presence of trans fats, high amounts of sugar, saturated fats and sodium. This law aimed to regulate the advertising of these products and promote healthy eating among children by prohibiting some marketing strategies. In 2019, black octagon-shaped labels began to be used as a warning of the excessive content of several nutrients (high in sodium, high in sugar, high in saturated fat, or containing trans fat). That same year, the Ministerio de Salud (MINSA) published the “Guidelines for the promotion and protection of healthy eating in public and private basic educational institutions”, which listed the foods recommended for sale in kiosks and school cafeterias and stated that they should be free of octagons 9.

In order to evaluate this public policy, it is essential to know whether the measures proposed by the State are met by the institutions. On the other hand, it is relevant to understand the factors related to the food environment of schools and their surroundings, such as street vending. Although there is no country-wide regulation of food sales in school environments, there are government commitments that can promote healthy eating habits, such as the Milan Pact, in which cities like Lima committed to promote healthier diets through strategies such as marketing standards for food and beverages for children.

This exploratory study aims to describe the supply of natural, processed, artisanal and ultra-processed foods as well as the advertising of processed and ultra-processed foods, in kiosks and surroundings of 15 schools in Metropolitan Lima, at the end of 2019. Our findings will be useful for designing larger studies to assess compliance with regulations, identify barriers and suggest changes to ensure that the objectives of Law 30021 8 are achieved; as well as the creation or improvement of other food policies that promote healthy food environments in schools.

KEY MESSAGES

Motivation for the study: Various regulations in the country seek to promote healthy eating in school children; however, the situation regarding food supply and advertising in school settings is unknown.

Main findings: The kiosks of the 15 evaluated schools offered ultra-processed foods; 73.3% offered at least one product with octagons and 60% advertised these foods. In 86.7% of the schools, there was food offered by street vendors, often processed or ultra-processed.

Implications: It is necessary to take action to comply with current standards in schools in order to promote healthy eating among children and adolescents.

THE STUDY

We carried out an observational, descriptive and cross-sectional study. Based on the researchers’ links with mothers of students and with teachers; 15 schools (9 public and 6 private) were selected for convenience, from ten Metropolitan Lima districts (Table 1).

Table 1 Characteristics of the schools included in the study.

| School | City district | Type | Educational level | Students | Number of kiosks/ cafeterias | Number of street vendors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Los Olivos | Private | P, S | 2,097 | 1 | 9 |

| 2 | Surco | Public | P, S | 671 | 2 | 0 |

| 3 | San Isidro | Private | P, S | 711 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | Villa El Salvador | Public | P, S | 400 | 2 | 7 |

| 5 | Miraflores | Private | P, S | 715 | 1 | 2 |

| 6 | Villa El Salvador | Public | P, S | 565 | 1 | 2 |

| 7 | Villa María del Triunfo | Public | P | ND | 1 | 5 |

| 8 | Surco | Private | P, S | 1,069 | 2 | 3 |

| 9 | Cercado de Lima | Public | P, S | 350 | 1 | 2 |

| 10 | Pueblo Libre | Public | S | 151 | 1 | 1 |

| 11 | Pueblo Libre | Public | S | 181 | 1 | 0 |

| 12 | La Molina | Private | P, S | 735 | 1 | 1 |

| 13 | Barranco | Private | P, S | 340 | 1 | 1 |

| 14 | Cercado de Lima | Public | P, S | 470 | 1 | 3 |

| 15 | Cercado de Lima | Public | P, S | 1093 | 1 | 10 |

P: primary; S: secondary; ND: no data

Between November and December 2019, we evaluated the food offered and the advertising of processed and ultra-processed food in kiosks and school cafeterias, as well as the food offered by street vendors located along the street in front of these institutions.

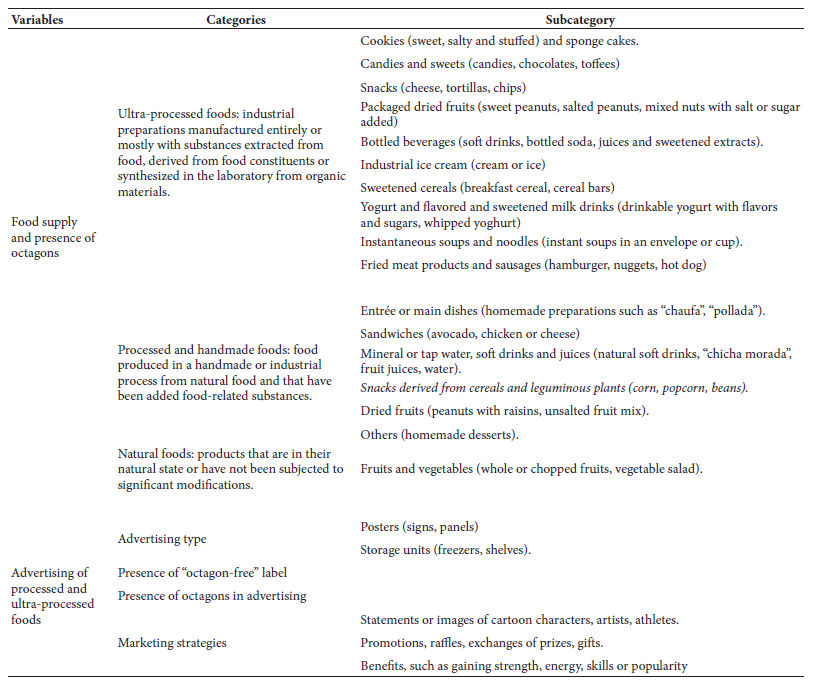

Information was obtained by observation. Inside the schools, both mothers and previously trained volunteer teachers completed an observation form during school hours. The researchers carried out the observation of food sale by street vendors after classes; information was collected in a similar observation form. The observation form, designed according to MINSA guidelines 9, allowed for the registration of a) the categories of food sold: (I) ultra-processed, (II) processed and artisanal foods, and (III) natural foods; b) the visible presence of octagons in them; and c) the characteristics of advertising for processed and ultra-processed foods (Table 2).

We carried out a univariate analysis of relative and absolute frequencies to describe the categories of food offered in educational institutions and by street vendors, the presence of octagons in each category and the presence of advertising. Data was analyzed with Stata 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

This protocol was exempted from review by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia (CAREG-ORVEI-158-19).

FINDINGS

We visited 15 educational institutions, 60% were public schools and 73% offered primary and secondary education. All of them were located within 10 districts of Metropolitan Lima. All had at least one kiosk or cafeteria, 20% (n = 3) had two, and the number of street vendors around the school varied from zero to ten (Table 1).

All institutions offered ultra-processed food at the school kiosks (Table 3). The most common products were cookies and cakes (100%, n = 15), followed by candies and sweets (86.7%, n = 13), bottled beverages (80%, n = 12) and sweetened cereals (80%, n = 12). In addition, at least one product with octagon(s) was observed in 73.3% (n = 11) of the schools. Regarding food with octagons, the most frequent categories we observed were candy and sweets (53.3%, n = 8), followed by bottled beverages (53.3%, n = 8), sweetened cereals (46.7%, n = 7), and snacks (46.7%, n = 7).

Table 3 Type of food offered and the presence of octagons in kiosks and school cafeterias.

| Type of food | Type of school | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of schools (%) | Public n (%) | Private n (%) | |

| Ultra-processed | |||

| Cookies and cakes | 15 (100.0) | 9 (60.0) | 6 (40.0) |

| With octagons | 6 (40.0) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) |

| Candies and sweets | 13 (86.7) | 9 (69.2) | 4 (30.8) |

| With octagons | 8 (53.3) | 6 (75.0) | 2 (25.0) |

| Bottled drinks | 12 (80.0) | 7 (58.3) | 5 (41.7) |

| With octagons | 8 (53.3) | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) |

| Sweetened Cereals | 12 (80.0) | 7 (58.3) | 5 (41.7) |

| With octagons | 7 (46.7) | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.9) |

| Snacks | 10 (66.7) | 6 (60.0) | 4 (40.0) |

| With octagons | 7 (46.7) | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.9) |

| Yogurt and sweetened and flavored milk drinks | 9 (60.0) | 5 (55.6) | 4 (44.4) |

| With octagons | 3 (20.0) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) |

| Packaged dried fruits | 8 (53.3) | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) |

| With octagons | 5 (33.3) | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) |

| Industrial ice cream | 5 (33.3) | 3 (60.0) | 2 (40.0) |

| With octagons | 3 (20.0) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) |

| Instant soups and noodles | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (100.0) |

| With octagons | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (100.0) |

| Fried meat and sausage products | 13 (86.7) | 7 (53.8) | 6 (46.2) |

| Processed and artisanal | |||

| Sandwiches | 14 (93.3) | 8 (57.1) | 6 (42.9) |

| Snacks derived from cereals and legumes | 14 (93.3) | 8 (57.1) | 6 (42.9) |

| Entrees and main dishes | 14 (93.3) | 9 (64.3) | 5 (35.7) |

| Water, soft drinks and juices | 13 (86.7) | 8 (61.5) | 5 (38.5) |

| Dried fruits | 9 (60.0) | 4 (44.4) | 5 (55.6) |

| Other products | 7 (46.6) | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.9) |

| Naturales | |||

| Fruits and/or vegetables | 14 (93.3) | 8 (57.1) | 6 (42.9) |

The percentages are expressed according to each category (row).

All schools also offered processed and artisanal foods. The most common were sandwiches, cereal and leguminous snacks, entrée or main courses, and fruits or vegetables, found in 93.3% of the schools (Table 3).

In kiosks or cafeterias of 9 schools (6 were public and 3 private) we observed advertising of processed and ultra-processed foods. In 8 schools (5 were public and 3 private) we found advertising on the food storage units (freezers or shelves); and in 2 public schools we observed advertising posters. One of the posters included octagons and others had cartoon characters and public figures. Neither advertisement offered gifts, prizes, or benefits such as gaining strength, gaining or losing weight, or gaining status or popularity. There was no advertising that showed that a product was “octagon-free”.

We found 47 food vendors near schools in 86.7% (n = 13) of the institutions. However, in two private institutions we did not find street food vendors. The average was 3.4 (Standard Deviation - SD: 3.3), and the maximum was 10 vendors per school. Of the total number of vendors, 61.7% (n = 29) offered ultra-processed food, and 34% (n = 16) offered food with octagons. Street vendors outside of the 13 schools offered at least one ultra-processed product. The most frequently observed products were cookies and cakes (84.6%, n = 11), followed by sweetened cereals (84.6%, n = 11), snacks (69.2%, n = 9) and candies (69.2%, n = 9). Street vendors outside of 84.6% (n=11) of the schools offered food with octagons. The most observed categories of food with octagons among schools with outside street vendors were cookies and cakes (69.2%, n = 9), snacks (61.5%, n = 8) and bottled beverages (53.8%, n = 7) (Table 4).

Table 4 Type of food offered and presence of octagons in food kiosks outside of schools.

| Type of food | Number of schools (%) | Type of school | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public n (%) | Private n (%) | ||

| Ultra-processed | |||

| Cookies and cakes | 11 (84.6) | 5 (45.5) | 6 (54.5) |

| With octagons | 9 (69.2) | 5 (55.6) | 4 (44.4) |

| Candies and sweets | 9 (69.2) | 5 (55.6) | 4 (44.4) |

| With octagons | 4 (30.8) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) |

| Bottled drinks | 8 (61.5) | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) |

| With octagons | 7 (53.8) | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.9) |

| Sweetened Cereals | 11 (84.6) | 5 (45.5) | 6 (54.5) |

| With octagons | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (100.0) |

| Snacks | 9 (69.2) | 4 (44.4) | 5 (55.6) |

| With octagons | 8 (61.5) | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) |

| Yogurt and sweetened and flavored milk drinks | 6 (46.2) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) |

| With octagons | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (100.0) |

| Packaged dried fruits | 3 (23.1) | 3 (100.0) | 0 (0) |

| With octagons | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Industrial ice cream | 3 (23.1) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) |

| With octagons | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (100.0) |

| Instant soups and noodles | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| With octagons | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Fried meat and sausage products | 2 (15.4) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) |

| Processed and artisanal | |||

| Homemade products | 3 (23.1) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) |

| Water, soft drinks and juices | 4 (30.8) | 4 (100.0) | 0 (0) |

| Snacks derived from cereals and legumes | 5 (38.5) | 4 (80.0) | 1 (20.0) |

| Dried fruits | 2 (15.4) | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0) |

| Sandwiches | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other products | 8 (61.5) | 6 (75.0) | 2 (25) |

| Naturales | |||

| Fruits and/or vegetables | 4 (30.8) | 4 (100.0) | 0 (0) |

The percentages are expressed according to each category (row).

Finally, 78.7% of the street vendors offered processed and artisanal products. Street vendors outside of the 13 schools offered processed and artisanal products. In several cases, we found different products than those offered at kiosks and cafeterias, such as homemade ice cream, homemade cakes or jelly.

DISCUSSION

We found that processed or ultra-processed food was offered inside all public and private schools, and that in the vast majority it was also offered by street vendors outside schools. Among the most frequently offered products, inside and outside the schools, we found cookies and cakes as well as bottled beverages, both with high energy density. In addition, in three out of four schools we observed products with octagons, which did not comply with recent MINSA guidelines 9.

It is important to note that, in all the kiosks, processed products were offered along with handmade products and healthy food, such as fruits and vegetables, natural beverages, as well as sandwiches, and entrees or main dishes. Although no information was registered on the quantity of products offered by category or the reception they had among students, the presence of natural foods and preparations made in the schools offers an opportunity to encourage consumption. Several interventions have succeeded in increasing the consumption of healthy food in schoolchildren, especially fruits and vegetables, such as educational interventions or free distribution of these products 10.

Considering the current legislation, another important finding was the presence of advertising of processed and ultra-processed foods in most of the public schools visited. In at least two institutions, the advertising did not comply with the regulation that, without being completely specific, prohibited the use of statements from cartoons and public characters to promote the consumption of this type of food 8. Just as the industry advertises processed products, the state and schools could do the same with healthier foods. Evidence suggests that exposure to fruit and vegetable advertising in educational institutions is associated with increased purchase and consumption of these products 10. In Peru, lower prices and increased visibility of fruits, accompanied by nutritional information, showed increased consumption at a Peruvian university, which also houses students from a pre-university center 11.

Our results, although not generalizable, suggest that the presence of street food vendors outside the institutions is common, and that they offer artisanal products as well as a variety of processed and ultra-processed products with octagons. The impact of food sales in the school surroundings on nutritional status has been demonstrated in other countries. In the United Kingdom, a positive association was observed between the presence of fast food on the way to school and the weight of students 12. A study in New Zealand found that the presence of food vendors around schools can influence the quality of the adolescents’ diets 13, while in the United States, food offered near schools was found to have high energy content 14.

The presence of a wide range of ultra-processed products with octagons, inside and outside almost all the schools visited, along with advertising, suggest the high exposure of children and adolescents to an unhealthy eating environment, which Law 30021 seeks to address 8. Our findings indicate that, at the end of 2019, the schools evaluated did not comply with current regulations. Furthermore, even if the schools did not offer or promote products with octagons, students would find them after school. Only some local governments have made efforts to regulate food sold outside of schools 15 - 17. It is noteworthy that some of the schools we evaluated are within the districts that have this type of regulation, so it is clear that there is still a long way to go before these measures have an impact.

Our results, although partial, have clear policy implications. First, it is necessary to promote the current regulation in public and private schools, in a clear and effective way. Then, a system for monitoring compliance must be established and it must be combined with innovative strategies to promote the consumption of healthy food. Next, dissemination, monitoring and promotion must include principals, teachers, vendors, parents and students, so that these actions translate into behavioral changes and that food environments are sustainable over time. Lastly, monitoring is needed in districts that have a policy on street vending around educational institutions and the commitment of other local governments to establish regulations that contribute to the promotion of healthy eating environments in schools.

Among the strengths of the study is the fact that it was carried out in the context of a current Peruvian law and that observations were made without prior notice. Limitations include having a small convenience sample, which reduces strength and the possibility of generalizing results. On the other hand, the observations were made in a single day, which did not capture the variation of product supply. Observation forms were filled according to each observer’s perspective (e.g., outside the kiosk). It is possible that not all the available products were registered or that food with octagons were outside the observer’s visual field. However, this is the offer and advertising to which school children are exposed, many of which could base their purchasing decision on the products they observe and the advertising or visual marketing techniques used on the packaging 18. Finally, the observations were limited to recording the presence of certain product categories, without evaluating the quantity or diversity of products offered in each category or sales, which would provide more and better information on the exposure and acceptance of the foods offered.

In conclusion, early findings and the lack of local studies suggest that an evaluation of this policy should be carried out with a larger sample and more detailed data collection, when face-to-face school classes are resumed.

Acknowledgements:

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of SALURBAL researchers. For a list of researchers, visit: https://drexel.edu/lac/salurbal/team/.

REFERENCES

1. Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Alimentos y bebidas ultraprocesados en América Latina: tendencias, efecto sobre la obesidad e implicaciones para las políticas públicas. Washington D.C.: OPS; 2019. Disponible en: https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/7698/9789275318645_esp.pdf?seque. [ Links ]

2. Corvalan C, Garmendia ML, Jones-Smith J, Lutter CK, Miranda JJ, Pedraza LS, et al. Nutrition status of children in Latin America. Obes Rev. 2017;18 Suppl 2:7-18. doi: 10.1111/obr.12571. [ Links ]

3. Hermoza-Moquillaza VH, Arellano-Sacramento C, Hermoza-Moquillaza RV, Lozano Aguilar VM. Relación entre ingesta de alimentos ultra procesados y los parámetros antropométricos en escolares. Rev Med Hered. 2019;30(2):68-75. doi: 10.20453/rmh.v30i2.3545. [ Links ]

4. Hanning RM, Luan H, Orava TA, Valaitis RF, Jung JKH, Ahmed R. Exploring Student Food Behaviour in Relation to Food Retail over the Time of Implementing Ontario's School Food and Beverage Policy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(14):2563. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16142563. [ Links ]

5. Heroux M, Iannotti RJ, Currie D, Pickett W, Janssen I. The food retail environment in school neighborhoods and its relation to lunchtime eating behaviors in youth from three countries. Health Place. 2012;18(6):1240-7. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.09.004. [ Links ]

6. Chacon V, Letona P, Villamor E, Barnoya J. Snack food advertising in stores around public schools in Guatemala. Crit Public Health. 2015;25(3):291-8. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2014.953035. [ Links ]

7. Azeredo CM, de Rezende LF, Canella DS, Claro RM, Peres MF, Luiz Odo C, et al. Food environments in schools and in the immediate vicinity are associated with unhealthy food consumption among Brazilian adolescents. Prev Med. 2016;88:73-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.03.026. [ Links ]

8. Congreso de la República del Perú. Ley N° 30021, Ley de Promoción de la alimentación saludable para niños, niñas y adolescentes. Lima: Congreso de la República; 2013. Disponible en: https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/normaslegales/decreto-supremo-que-aprueba-el-reglamento-de-la-ley-n-30021-decreto-supremo-n-017-2017-sa-1534348-4/. [ Links ]

9. Ministerio de Salud. Resolución Ministerial N° 195-2019-MINSA. Lineamimentos para la promoción y protección de la alimentación saludable en instituciones educativas, públicas y privadas de la educación básica. Lima: MINSA; 2019. Disponible en: https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/296301/RM_N__195-2019-MINSA.PDF. [ Links ]

10. Evans CE, Christian MS, Cleghorn CL, Greenwood DC, Cade JE. Systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based interventions to improve daily fruit and vegetable intake in children aged 5 to 12 y. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(4):889-901. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.030270. [ Links ]

11. Cardenas MK, Benziger CP, Pillay TD, Miranda JJ. The effect of changes in visibility and price on fruit purchasing at a university cafeteria in Lima, Peru. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(15):2742-9. doi: 10.1017/S1368980014002730. [ Links ]

12. Green MA, Radley D, Lomax N, Morris MA, Griffiths C. Is adolescent body mass index and waist circumference associated with the food environments surrounding schools and homes? A longitudinal analysis. BMC public health. 2018;18(1):482. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5383-z. [ Links ]

13. Clark EM, Quigg R, Wong JE, Richards R, Black KE, Skidmore PM. Is the food environment surrounding schools associated with the diet quality of adolescents in Otago, New Zealand?. Health Place. 2014;30:78-85. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.08.008. [ Links ]

14. Borradaile KE, Sherman S, Vander Veur SS, McCoy T, Sandoval B, Nachmani J, et al. Snacking in children: the role of urban corner stores. Pediatrics. 2009;124(5):1293-8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0964. [ Links ]

15. Municipalidad Distrital de Villa María del Triunfo. Ordenanza Nº 214-2016/MVMT. Regulan la Alimentación Saludable - Entornos Saludables en Instituciones Educativas y Alrededores, y declaran de interés distrital la Promoción, Prevención, Control, y Vigilancia de los Alimentos Saludables en las Instituciones Educativas en el Distrito de Villa María. Lima: MVMT; 2016. Disponible en: https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/normaslegales/regulan-la-alimentacion-saludable-entornos-saludables-en-i-ordenanza-no-214-2016mvmt-1351534-1/. [ Links ]

16. Municipalidad Distrital de Barranco. Ordenanza Nº 448-MDB. Ordenanza que regula la alimentación saludable y fomento de entornos saludables en instituciones educativas y alrededores Lima: MDB; 2016. Disponible en: https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/normaslegales/ordenanza-que-regula-la-alimentacion-saludable-y-fomento-de-ordenanza-n-448-mdb-1491301-1/. [ Links ]

17. Municipalidad Metropolitana de Lima. Ordenanza N° 082-MML. Ordenanza de Salud y Salubridad Municipal. Lima: MML; 1995. Disponible en: http://www.munlima.gob.pe/images/descargas/licencias-de-funcionamiento/legislacion/22-ORDENANZA-082-MML.pdf. [ Links ]

18. Theben A, Gerards M, Folkvord F. The Effect of Packaging Color and Health Claims on Product Attitude and Buying Intention. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6):1991. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17061991. [ Links ]

Funding: This work was carried out as part of the auxiliary study of the Urban Health Project in Latin America (SALURBAL): “Evaluating the implementation and effects of advertising warnings on food labeling in Peru: A study of mixed methods”. The SALURBAL project is funded by the Wellcome Trust’s “Our Planet, Our Health” initiative (grant 205177/Z/16/z).

Cite as: Saavedra-Garcia L, Meza-Hernández M, Yabiku-Soto K, Hernández-Vásquez A, Kesar HV, et al. Food and beverage supply and advertising in schools and their surroundings in metropolitan Lima. An exploratory study. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2020;37(4): 726-32. doi: https://doi.org/10.17843/rpmesp.2020.374.5838.

Received: May 20, 2020; Accepted: August 05, 2020

text in

text in