Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Horizonte Médico (Lima)

versión impresa ISSN 1727-558X

Horiz. Med. vol.23 no.2 Lima abr./jun. 2023 Epub 30-Mayo-2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.24265/horizmed.2023.v23n2.01

Original article

The feeling of loneliness among the elderly population attending day care centers in Bogotá, Colombia

1 Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Bogotá, Colombia

2 Hospital Universitario San Ignacio. Bogotá, Colombia

Objective:

To identify the factors associated with the categories of loneliness among the elderly population attending day care centers in Bogotá, Colombia.

Materials and methods:

An analytical, cross-sectional and quantitative study was carried out to measure the loneliness among older people attending a day care center in the city of Bogotá between November 2020 and June 2021 using the ESTE scale. To meet the objective, a univariate descriptive statistical analysis was performed, such that, for the quantitative variables, the mean with standard deviation or median with interquartile ranges were used, in accordance with the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality, and for the categorical variables, absolute frequencies and proportions were used. The bivariate analysis was conducted using Student’s t-test and chi-square test (p < 0.05), which contributed to build a logistic regression model with statistically significant variables.

Results:

A total of 215 elderly people with a mean age of 70.5 years were included in the study: 72 % were females, 56.5 % had primary education, 38.6 % were single and 67.4 % had a history of chronic non-communicable disease. According to the ESTE scale, the study subjects showed a low level of family loneliness (67 %), a high and medium level of marital loneliness (79 %), a high and medium level of social loneliness (51 %) and a high and medium level of adaptation crisis (43 %). It was found that marital loneliness was associated with females (p = 0.001), social loneliness with lower class (p = 0.027) and adaptation crisis with lower class (p = 0.024).

Conclusions:

The factors associated with the feeling of loneliness among the elderly population attending day care centers are, in the marital loneliness category, being a woman and, in the social loneliness and adaptation crisis categories, belonging to the lower class.

Keywords: Loneliness; Aged; Chronic Disease

Introduction

The dynamics of population aging worldwide has aroused interest in responding to the social and health needs of the elderly population due to the increased demand for health services 1,2. According to ECLAC’s Centro Latinoamericano y Caribeño de Demografía (CELADE - Latin American and Caribbean Demographic Centre) and the World report on ageing and health released by the World Health Organization (WHO), the Latin American and Caribbean population will account for three to five times the global population between 2025 and 2050, and its population over 65 years of age will be larger than that of children under 14 3,4.

This process of population growth of the elderly is characterized by the increase in life expectancy, which gives rise to longer-lived populations who need more health and social care 2, the generation of challenges in dealing with the elderly, as well as the creation of healthy conditions or environments 5. In the case of the Colombian population, according to the 2005 census conducted by Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística (DANE National Administrative Department of Statistics), people over 65 years of age made up 6.5 % of the population, and an increase of 20 % is projected for 2050 6.

The elderly population is characterized by a burden of chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 7,8. The prevalent morbidity in the elderly includes mental disorders, as stated by the Encuesta Nacional de Salud, Bienestar y Envejecimiento (SABE - National Survey on Health, WellBeing and Aging), where 40 % of the population have hypertension and symptoms of depression, the latter represented by a burden of mental disorders secondary to the typical changes and adaptations of old age 9-11.

Among the main phenomena in the elderly is loneliness, which is considered a multidimensional construct associated with mental health disorders. Similarly, pathologies related to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, such as cardiovascular risk, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, sleep disorders, migraine, altered immune function and effects on the transcription of some genes, can also be mentioned 12,13. According to a systematic review conducted by Petitte et al., it was found that the feeling of loneliness has a prevalence of 20 % to 40 % in the elderly population 14.

Loneliness means feeling lonely, regardless of the number of social contacts 15. There are different types of loneliness and some authors identify unwanted loneliness 16, whether objective or subjective. Rubio and Aleixandre 17, as well as Yaben 18, draw a distinction between being alone and feeling lonely. Objective loneliness refers to being alone, while subjective or emotional loneliness refers to feeling lonely. For this reason, it is necessary to assess subjective loneliness using different measurement scales 5.

Currently, there are loneliness assessment scales, including the UCLA Loneliness Scale, the Social and Emotional Loneliness Scale for Adults (SELSA), the Emotional/Social Loneliness Inventory (ESLI) and the Philadelphia Scale 19-21. The Spanish ESTE scale, already validated in Colombia with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90, consists of 30 items and measures family loneliness, marital loneliness, social loneliness and adaptation crisis. The research used selfadministered Likert-type questions. The administration of such scale within the gerontological assessment will allow identifying and preventing the feeling of loneliness 19,20,22.

It is worth mentioning that loneliness in the elderly involves the intervention of different health disciplines which seek to promote people to be active subjects in their adaptation process during their lives, in order to contribute to reducing the burden of disease. It should be noted that loneliness has an impact not only on mental disorders but also on physical conditions 23, since it has been shown that self-care and adherence to treatment are diminished in people who experience this feeling.

The present study aimed at identifying the factors associated with the categories of loneliness in the elderly population attending day care centers in Bogotá, Colombia, to promote activities for the prevention of loneliness. It should be emphasized that preventing loneliness supports the aging process proposed by the Colombian policy on human aging and old age, as well as the increase in wellbeing in all areas of health of elderly people 24, and even more in the framework of the decade of healthy aging 2020-2030.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

This is a descriptive, observational, analytical and crosssectional study, where a characterization survey and the ESTE scale were administered to measure loneliness 19 in elderly people attending day care centers of Secretaría Distrital de Integración Social (SDIS District Secretariat for Social Integration) in the city of Bogotá from November 2020 to June 2021.

Variables and measurements

The dependent variable was loneliness, which was assessed by the ESTE scale and presented as a dichotomous nominal qualitative variable. The ESTE scale consisted of 30 questions rated by a 5-point Likert scale with the following options: always, very often, sometimes, rarely and never. It included four categories of loneliness: family loneliness, marital loneliness, social loneliness and adaptation crisis. Family loneliness had four items, marital loneliness five, social loneliness eight and adaptation crisis thirteen. Conventionally, it is understood that the lower the score, the lower the risk of loneliness, with cut-off points that allow establishing low risk, medium risk and high risk. It was organized as a dichotomous variable: YES (medium and high risk), NO (low risk), according to the cut-off points 25. As for the independent variables, sex (male or female), age (years), marital status (married, single, widowed, divorced and living common-law), educational level (no education, primary education, secondary education, technical education, professional education), socioeconomic status (upper, middle and lower class), type of housing (owned, rented, subleased and others) and number of people with whom the patient lives were organized as sociodemographic variables; number of comorbidities as a continuous variable; and history of NCD as a dichotomous variable.

A simple random sampling was conducted using a list of the day care center participants who had the same possibility of taking part in the study. This fact reduced the risk of bias and ensured that the information obtained from the study could be replicated in populations with similar characteristics. The research included 215 people from a sample of 500 whose expected proportion of loneliness was 40 %, with a statistical power of 95 % and an error of 5 %. The inclusion criteria were being 60 years of age or older and attending a day care center. The exclusion criteria were the unwillingness to participate in the study.

After being invited to participate in the study and signing the informed consent form, telephone calls were made, the questionnaire with the abovementioned variables was administered and the information was recorded in an electronic database, thus guaranteeing data anonymization.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis of the information was performed. For the continuous variables, means and standard deviations were reported in the case of normally distributed variables, or medians and interquartile ranges in the case of non-normally distributed variables. Concerning the categorical variables, frequency and/or percentage tables were created. For the bivariate analysis, Student’s t-test (normal distribution, quantitative variables) and chi-square test (categorical variables) were used with a statistical significance of p < 0.05. To estimate the nonparametric distribution, the Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests were employed. To determine the association between the categorical dependent variable (dichotomized loneliness variable) and statistically significant factors, a multivariate logistic regression model was built and adjusted by age.

The data was analyzed using the Stata Statistical Software: Release 16.1. The level of statistical significance was set at a p value < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

The research protocol was approved and authorized by the Research and Ethics Committee (REC) of the School of Nursing at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana and the SDIS Departamento Administrativo de Diseño Estratégico (DADE Administrative Department of Strategic Design). Moreover, it was classified as minimal risk under the terms of the Colombian law. The interviews were conducted by the researchers to protect data confidentiality and patient privacy. The data was recorded in a database with restricted access using the participants’ coding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest; therefore, the results respect the principle of veracity.

Results

The research included 215 elderly people whose mean age was 70.5 years with a SD of 6.90 and 72 % of whom were females. In relation to the marital status, 38.60 % (n = 83) were single, followed by widowed with 21.40 % (n = 46). Fifty-six percent (n = 121) had primary education and 60.90 % (n = 131) belonged to the middle class (socioeconomic status 3). Regarding the number of comorbidities, a median of 1 (IQR 0-1) was found (Table 1).

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of the population at day care centers

| Sociodemographic characteristics (N = 215) | |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 70.50 (6.90) |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 155 (72.10 %) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Married | 28 (13.00 %) |

| Single | 83 (38.60 %) |

| Widowed | 46 (21.40 %) |

| Divorced | 33 (15.40 %) |

| Living common-law | 25 (11.60 %) |

| Educational level, n (%) | |

| No education | 14 (6.50 %) |

| Primary education | 121 (56.50 %) |

| Secondary education | 57 (26.60 %) |

| Technical education | 14 (6.50 %) |

| Professional education | 8 (3.70 %) |

| Socioeconomic status, n (%) | |

| Lower class | 84 (39.10 %) |

| Middle class | 131 (60.90 %) |

| Type of housing, n (%) | |

| Owned | 54 (25.10 %) |

| Rented | 132 (61.40 %) |

| Subleased | 6 (2.80 %) |

| Others | 23 (10.70 %) |

| Number of people with whom the patient lives, median (IQR) | 2 (1-3) |

| Chronic disease | |

| History of chronic NCD, YES, n (%) | 145 (67.40 %) |

| Number of comorbidities, median (IQR) | 1 (0-1) |

SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range; NCD: non-communicable disease.

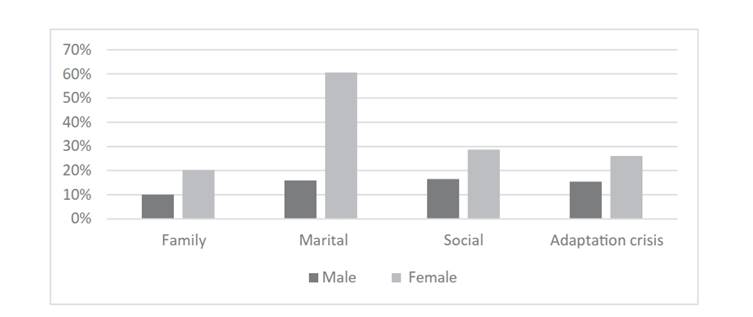

According to the ESTE scale and the measurement of family loneliness, marital loneliness, social loneliness and adaptation crisis, 67 % (n = 143) of the study subjects showed a low level of family loneliness, 79 % (n = 170) a high and medium level of marital loneliness, 51 % (n = 108) a high and medium level of social loneliness, and 43 % (n = 92) a high and medium level of adaptation crisis (existential loneliness) (Table 2). Similarly, a data analysis by dimensions revealed that, in all dimensions, women experience higher levels of loneliness than men (Figure 1).

Table 2 Description of ESTE scale dimensions by levels

| Family loneliness | Marital loneliness | Social loneliness | Adaptation crisis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High, n (%) | 39 (18.20 %) | 162 (75.00 %) | 29 (13.60 %) | 14 (6.50 %) |

| Medium, n (%) | 32 (14.90 %) | 8 (3.70 %) | 79 (37.10 %) | 78 (36.30 %) |

| Low, n (%) | 143 (66.80 %) | 46 (21.30 %) | 105 (49.30 %) | 123 (57.20 %) |

For the bivariate analysis, a level of statistical significance (p < 0.05) was considered in the different dimensions of family loneliness, marital loneliness, social loneliness and adaptation crisis as shown in Table 3, which presents statistically significant variables in each of the dimensions included in the logistic regression models.

Table 3 Bivariate analysis between the dimensions of loneliness and independent variables

| Family loneliness | Marital loneliness | Social loneliness | Adaptation crisis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | p value | Yes | No | p value | Yes | No | p value | Yes | No | p value | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 69.1 | 71.20 | 0.03 | 70.60 | 70.10 | 0.67 | 69.70 | 71.30 | 0.09 | 69.60 | 71.10 | 0.11 |

| (6.60) | (6.90) | (7.10) | (6.30) | (6.20) | (7.40) | (6.25) | (7.30) | |||||

| Sex, female, n (%) | 43 | 111 | 0.01 | 130 | 25 | 0.002 | 67 | 85 | 0.01 | 55 | 100 | 0.01 |

| (27.90 %) | (72.10 %) | (83.80 %) | (16.10 %) | (43.80 %) | (56.20 %) | (35.50 %) | (64.50 %) | |||||

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Married | 7 | 21 | 0.30 | 14 | 14 | < 0.01 | 13 | 15 | 0.60 | 9 | 19 | 0.20 |

| (9.80 %) | (14.80 %) | (8.20 %) | (30.40 %) | (12.04 %) | (14.40 %) | (9.78 %) | (15.45 %) | |||||

| Single | 33 | 49 | 0.09 | 80 | 3 | < 0.01 | 52 | 29 | 0.01 | 40 | 43 | 0.20 |

| (46.40 %) | (34.50 %) | (47.30 %) | (6.50 %) | (48.1 %) | (27.80 %) | (43.50 %) | (34.90 %) | |||||

| Widowed | 11 | 35 | 0.12 | 42 | 4 | 0.01 | 16 | 30 | 0.01 | 19 | 27 | 0.81 |

| (15.50 %) | (24.70 %) | (24.85 %) | (8.70 %) | (14.8 %) | (28.80 %) | (20.70 %) | (21.90 %) | |||||

| Divorced | 15 | 18 | 0.10 | 31 | 2 | 0.02 | 15 | 18 | 0.73 | 15 | 77 | 0.73 |

| (21.13 %) | (12.70 %) | (18.30 %) | (4.35 %) | (16.3 %) | (14.60 %) | (45.40 %) | (42.30 %) | |||||

| Living common-law | 5 | 19 | 0.16 | 2 | 23 | < 0.01 | 13 | 11 | 0.73 | 9 | 16 | 0.46 |

| (7.0 %) | (13.40 %) | (1.18 %) | (50 %) | (12.04 %) | (10.50 %) | (9.78 %) | (13.01 %) | |||||

| Socioeconomic status, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| 31 | 52 | 0.32 | 65 | 19 | 0.73 | 53 | 30 | 0,01 | 47 | 37 | 0.01 | |

| Lower class | (43.66 %) | (36.62 %) | (38.46 %) | (41.30 %) | (49.07 %) | (28.85 %) | (51.09 %) | (30.08 %) | ||||

| Type of housing, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Owned | 13 | 41 | 0.09 | 41 | 13 | 0.58 | 27 | 27 | 0.872 | 23 | 31 | 0.97 |

| (18.31 %) | (28.87 %) | (24.26 %) | (28.26 %) | (25 %) | (25.95 %) | (25 %) | (25.20 %) | |||||

| Rented | 49 | 82 | 0.11 | 103 | 29 | 0.80 | 67 | 62 | 0.72 | 55 | 77 | 0.67 |

| (69.01 %) | (57.75 %) | (60.93 %) | (63.04 %) | (62.04 %) | (59.62 %) | (69.78 %) | (62.60 %) | |||||

| Subleased | 3 | 2 | 0.20 | 6 | 0 | 0.19 | 2 | 4 | 0.38 | 2 | 4 | 0.64 |

| (4.23 %) | (1.41 %) | (3.55 %) | (0.00 %) | (1.85 %) | (3.85 %) | (2.17 %) | (3.25 %) | |||||

| Others | 6 | 17 | 0.43 | 19 | 4 | 0.62 | 12 | 11 | 0.90 | 12 | 11 | 0.34 |

| (8.45 %) | (11.97 %) | (11.94 %) | (8.70 %) | (11.11 %) | (10.58 %) | (13.04 %) | (12.94 %) | |||||

| Number of people with whom the patient lives, median (IQR) | 1 | 2 | < 0.01 | 1 | 2.50 | 0.00 | 1 | 2 | 0.12 | 1 | 2 | 0.01 |

| (0-2) | (1-4) | (0-3) | (1-3) | (0-3) | (1-4) | (0-2) | (1-4) | |||||

| Chronic disease | ||||||||||||

| History of chronic NCD, YES, n (%) | 41 | 103 | 0.03 | 115 | 30 | 0.72 | 66 | 77 | 0.045 | 57 | 88 | 0.14 |

| (57.75 %) | (42.74 %) | (68.05 %) | (65.22 %) | (61.11 %) | (74.04 %) | (61.96 %) | (71.54 %) | |||||

| Number of comorbidities, median (IQR) | 1 | 1 | 0.14 | 1 | 1 | 0.13 | 1 | 1 | 0.03 | 1 | 1 | 0.38 |

| (0-1) | (0-2) | (0-2) | (0-1) | (0-1) | (0-2) | (0-1.50) | (0-1) |

SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range; NCD: non-communicable disease.

In relation to family loneliness, 28 % (n = 43) of the 155 participating women showed this type of loneliness with statistical significance (p < 0.01), 57.8 % (n = 41) had a history of chronic NCD (p = 0.03) and the number of people with whom the patient lives accounted for a median of 1 (IQR 0-1) (p < 0.01).

Concerning marital loneliness, 83.3 % (n = 130) of the participating women showed this type of loneliness with a statistical significance of p = 0.01. Regarding the marital status, statistical significance was found in all categories; however, they were not included in the regression model because of the collinearity effect. In relation to the number of people with whom the patient lives, p = 0.01 with a median of 1 (IQR 1-3) was found.

In the dimension of social loneliness, the statistically significant variables (p < 0.05) were female sex (p = 0.01), lower class (p = 0.01), history of chronic NCD (p = 0.04) and number of comorbidities (p = 0.03). Furthermore, in adaptation crisis, similar data was found in relation to sex and lower class.

In the logistic regression model, associations were found in the following variables according to each dimension: in marital loneliness, an adjusted OR = 3.15 (95 % CI: 1.55-6.39) related to female sex; in social loneliness, an adjusted OR = 1.95 (95 % CI: 1.08-3.52) related to lower class; and in adaptation crisis, an adjusted OR = 1.99 (95 % CI: 1.09-3.63) related to lower class (Table 4).

Discussion

The feeling of loneliness in the elderly population has an impact and a prevalence of 40 % and is related to the development of both physical and mental chronic NCDs 14. Therefore, the timely detection of loneliness will allow health teams to develop strategies for disease prevention and health promotion.

Through the ESTE scale-which has already been validated in the Colombian population-the study found that the most frequent dimension of loneliness was related to marital loneliness, followed by social loneliness, adaptation crisis and, finally, family loneliness. In addition, it was associated with female sex and lower class. In accordance with the research carried out by Garza-Sánchez et al. 26, similar data was found for the dimension of marital loneliness in Spanish women.

As for sex, the results of this study agree with others’: women show higher levels of loneliness 26. Regarding the age, the results of the bivariate analysis were significant in the dimensions of family and social loneliness, which were similar to those found in other populations 27.

This research work also showed, in general terms, that the sample of older adults had a low educational level and, unlike previous studies, it was not associated with a higher level of loneliness in any of the dimensions 26-28. Concerning the marital status, a statistically significant association was found in the dimension of marital loneliness, as expected 27.

The low socioeconomic status showed a significant outcome in the dimensions of loneliness and adaptation crisis. Thus, it is important to examine and work on the adaptation crisis: a task that involves not only older adults but also the population that someday will become adults and should prepare themselves to reach this age from the approach of healthy aging 29.

As for the number of people with whom the patient lives, the results of the bivariate analysis were not significant in the dimension of social loneliness. However, it was significant in the other dimensions, so that living commonlaw and having a relationship were important variables 30.

Chronic NCDs were common in the study population and are generally frequent in older adults. It was significantly associated with the dimensions of family and social loneliness in the bivariate analysis but not significantly in the adjusted analysis. Furthermore, the number of comorbidities was low and showed a nonsignificant association in the regression model.

Regarding the limitations, as this was a cross-sectional study, only one measurement was taken. Therefore, the levels of loneliness and the associations resulting from the survey should be carefully examined and verified with another type of study, which will prevent a lower causality. Concerning the strengths, the ESTE scale, a validated tool in the Colombian population, was used to evaluate loneliness, and the expected sample size was reached. Since the population came from day care centers, a simple random sampling of all the people attending the center was performed to control the selection bias.

In conclusion, the feeling of loneliness is characteristic of women and single or widowed people. However, the results found in family loneliness should be highlighted, given that there is no evidence of high and/or medium levels.

Author contributions: CMCR and DACHC conceived the idea of the manuscript, collected the data, collaborated with the critical editing of the manuscript and approved the final version for publication. In addition, DACHC conducted the analysis of the study and CMCR wrote the first draft of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

1. Segura-Cardona A, Cardona-Arango D, Segura-Cardona A, Garzon-Duque M. Riesgo de depresion y factores asociados en adultos mayores. Antioquia, Colombia. 2012. Rev Salud Publica. 2015;17(2):184-94. [ Links ]

2. Rivillas JC, Gomez-Aristizabal L, Rengifo-Reina HA, Munoz-Laverde EP. Envejecimiento poblacional y desigualdades sociales en la mortalidad del adulto mayor en Colombia. Rev Fac Nac Salud Publica. 2017;35(3):369-81. [ Links ]

3. Red de Desarrollo Social de America Latina y el Caribe. Informe mundial de la salud 2015. El envejecimiento y la salud [Internet]. Ginebra: OMS; 2015 p. 1-29. [ Links ]

4. Comision Economica para America Latina y el Caribe. Las personas mayores en America Latina y el Caribe: diagnostico sobre la situacion y las politicas. Sintesis. Santiago de Chile: CEPAL; 2023 p. 1-49. [ Links ]

5. Camargo-Rojas CM, Chavarro-Carvajal DA. El sentimiento de soledad en personas mayores: conocimiento y tamizacion oportuna. Univ Medica. 2020;61(2):64-71. [ Links ]

6. Arango VE, Ruiz IC. Diagnostico de los adultos mayores en Colombia. Fund Saldarriaga Concha. Bogota. 2006, p. 1-19. [ Links ]

7. Penaloza RE, Salamanca N, Rodriguez JM, Rodriguez J, Beltran AR. Estimacion de la carga de enfermedad para Colombia, 1a ed. Bogota: Editorial Pontificia Universidad Javeriana; 2014. 1-153 p. [ Links ]

8. Montes J, Casariego E, de Toro M, Mosquera E. La asistencia a pacientes cronicos y pluripatologicos. Magnitud e iniciativas para su manejo: La Declaracion de Sevilla. Situacion y propuestas en Galicia. Galicia Clin. 2012;73(Supl 1):S7-S14. [ Links ]

9. Bekhet AK, Zauszniewski JA. Mental health of elders in retirement communities: Is loneliness a key factor? Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2012;26(3):214-24. [ Links ]

10. Ministerio de Salud y Proteccion Social. Sabe Colombia 2015: Estudio nacional de salud, bienestar y envejecimiento. Colombia: MINSALUD; 2016 p. 1-11. [ Links ]

11. Bohorquez P, Nieto MD, Pascual B, Garcia MJ, Ortiz MA, Bernabeu M. Validacion de un modelo pronostico para pacientes pluripatologicos en atencion primaria: Estudio PROFUND en atencion primaria. Aten Primaria. 2014;46:41-8. [ Links ]

12. Montejo-Carrasco P, Prada-Crespo D, Montejo-Rubio C, MontenegroPena M. Loneliness in the Elderly: Association with Health Variables, Pain, and Cognitive Performance. A Population-based Study. Clin Salud. 2022;33(2):51-8. [ Links ]

13. Theeke LA. Predictors of Loneliness in U.S. Adults Over Age SixtyFive. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2009;23(5):387-96. [ Links ]

14. Petitte T, Mallow J, Barnes E, Petrone A, Barr T, Theeke L. A Systematic Review of Loneliness and Common Chronic Physical Conditions in Adults. Open Psychol J. 2015;8(Suppl 2):113-32. [ Links ]

15. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Opportunities for the health care system. Washington D.C.: National Academies Press; 2020. [ Links ]

16. Martin U, Gonzalez-Rabago Y. Soledad no deseada, salud y desigualdades sociales a lo largo del ciclo vital. Gac Sanit. 2021;35(5):432-7. [ Links ]

17. Rubio R, Aleixandre M. La escala »,» ®,® §,§ ­, ¹,¹ ²,² ³,³ ß,ß Þ,Þ þ,þ ×,× Ú,Ú ú,ú Û,Û û,û Ù,Ù ù,ù ¨,¨ Ü,Ü ü,ü Ý,Ý ý,ý ¥,¥ ÿ,ÿ ¶,¶ ESTE »,» ®,® §,§ ­, ¹,¹ ²,² ³,³ ß,ß Þ,Þ þ,þ ×,× Ú,Ú ú,ú Û,Û û,û Ù,Ù ù,ù ¨,¨ Ü,Ü ü,ü Ý,Ý ý,ý ¥,¥ ÿ,ÿ ¶,¶ , un indicador objetivo de soledad en la tercera edad. Geriatrika. 1999;5(9):26-35. [ Links ]

18. Yaben SY. Adaptacion al castellano de la Escala para la Evaluacion de la Soledad Social y Emocional en adultos SESLA-S. Rev Int Psicol Ter Psicol. 2008;8(1):103-16. [ Links ]

19. Cardona JL, Villamil MM, Henao E, Quintero A. Validacion de la escala para medir la soledad de la poblacion adulta. Invest Educ Enferm. 2010;28(3):416-27. [ Links ]

20. Cerquera AM, Cala ML, Galvis MJ. Validacion de constructo de la escala ESTE-R para medicion de la soledad en la vejez en Bucaramanga, Colombia. Divers: Perspect Psicol. 2013;9(1):45-53. [ Links ]

21. Bermeja AI, Ausin B. Programas de combate a la soledad en ancianos institucionalizados: Una revision de la literatura cientifica. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol. 2018;53(3):155-64. [ Links ]

22. Cardona JL, Villamil MM, Henao E, Quintero A. Variables asociadas con el sentimiento de soledad en adultos que asisten a programas de la tercera edad del municipio de Medellin. Med UPB. 2015;34(2):102-14. [ Links ]

23. Rodriguez M. La soledad en el anciano. Gerokomos. 2009;20(4):159-66. [ Links ]

24. Ministerio de la Proteccion Social. Politica Nacional de Envejecimiento y Vejez. Colombia: MPS; 2011 p. 1-49. [ Links ]

25. Cantuna CA, Hidalgo A, Pereira H. Relacion del sentimiento de soledad y el estado de salud de los adultos mayores que acuden al Centro Medico Tierra Nueva, mediante la aplicacion del cuestionario SF-36 y escala ESTE, periodo febrero-mayo del 2015 [tesis de titulo]. [Quito]: Pontificia Universidad Catolica del Ecuador; 2015. [ Links ]

26. Garza-Sanchez RI, Gonzalez-Tovar J, Rubio-Rubio L, DumitracheDumitrache CG. Soledad en personas mayores de Espana y Mexico: un analisis comparativo. Acta Colomb Psicol. 2020;23(1):106-16. [ Links ]

27. Acosta CO, Tanori J, Garcia R, Echeverria SB, Vales JJ, Rubio L. Soledad, depresion y calidad de vida en adultos mayores mexicanos. Psicol y Salud. 2017;27(2):179-88. [ Links ]

28. Hawkley LC, Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Masi CM, Thisted A, Cacioppo JT. From Social Structural Factors to Perceptions of Relationship Quality and Loneliness: The Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;63B(6):S375-S84. [ Links ]

29. Organizacion Mundial de la Salud. Decada del envejecimiento saludable 2020-2030 [Internet]. Ginebra: OMS; 2019 p. 1-7. Disponible en: https://www.who.int/es/publications/m/item/ decade-of-healthy-ageing-plan-of-action [ Links ]

30. Gonzalez-Tovar J, Garza-Sanchez RI. La medicion de soledad en personas adultas mayores: estructura interna de la escala ESTE en una muestra del norte de Mexico. Interdisciplinaria. 2021;38(3):169-84. [ Links ]

Received: December 13, 2022; Revised: January 31, 2023; Accepted: February 13, 2023

texto en

texto en