Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO  uBio

uBio

Compartir

Revista Peruana de Biología

versión On-line ISSN 1727-9933

Rev. peru biol. v.17 n.1 Lima abr. 2010

TRABAJOS ORIGINALES

Analysis of the secondary structure of mitochondrial LSU rRNA of Peruvian land snails (Orthalicidae: Gastropoda)

Análisis de la estructura secundaria del LSU rRNA mitocondrial de caracoles terrestres peruanos (Orthalicidae: Gastropoda)

Jorge Ramirez1, 2 ; Rina Ramírez1, 2

1 Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos.

2 Museo de Historia Natural, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. Av. Arenales 1256, Apartado 14-0434, Lima-14, Perú.

Email Jorge Ramirez: jolobio@hotmail.com

Abstract

The alignment of ribosomal genes is difficult due to insertion and deletion events of nucleotides, making the alignment ambiguous. This can be overcome by using information from the secondary structure of ribosomal genes. The aim of this study was to evaluate the utility of the secondary structure in improving the alignment of the 16S rRNA gene in land snails of the family Orthalicidae. We assessed 10 Orthalicid species (five genera). Total DNA was isolated and the partial 16S rRNA gene was amplified and sequenced using internal primers. The sequences were aligned with ClustalX and manually corrected, in DCSE format, using the 16S rRNA secondary structure of Albinaria caerulea (Pulmonata: Clausiliidae). The sequences obtained ranged from 323 to 345 bp corresponding to parts of both domains IV and V of the 16S rRNA gene. The secondary structure was recovered by homology using RnaViz 2.0. Most stems are conserved, and in general the loops are more variable. The compensatory mutations in stems are related to maintenance of the structure. The absence of a bulge-stem-loop in domain V places the family Orthalicidae within the Heterobranchia.

Keywords: 16S rRNA, Mollusca, Bulimulinae, DCSE, Compensatory Mutations.

Resumen

El alineamiento de genes ribosomales es dificultoso debido a eventos de inserción y deleción de nucleótidos, convirtiendo el alineamiento en ambiguo; esto puede ser superado utilizando la información de la estructura secundaria. El objetivo del presente trabajo es evaluar la utilidad de la estructura secundaria en mejorar el alineamiento del gen 16S rRNA de caracoles terrestres de la familia Orthalicidae. Se evaluaron 10 especies de Orthalicidos (5 géneros). El ADN total fue aislado y parte del gen 16S rRNA fue amplificado y secuenciado usando primers internos. Las secuencias fueron alineadas con ClustalX y corregidas a mano, en formato DCSE, usando la estructura secundaria del 16S rRNA de Albinaria caerulea (Pulmonata: Clausiliidae). Las secuencias obtenidas variaron de 323 a 345 pb correspondiendo a partes del dominio IV y V del gen 16S rRNA. Se pudo recuperar por homología la estructura secundaria para los Orthalicidos usando RnaViz 2.0. La mayoría de las hélices son conservadas, siendo en general los bucles más variables. El fenómeno de mutaciones compensatorias en las hélices, estaría relacionado con la conservación de la estructura. La ausencia de un "bulge-stem-loop" en el dominio V ubica a la familia Orthalicidae dentro de Heterobranchia.

Palabras claves: 16S rRNA, Mollusca, Bulimulinae, DCSE, Mutaciones Compensatorias.

Introduction

Phylogenetic molecular studies aim to recover the historical signal stored along the evolution in the sequences of nucleotides or amino acids. The alignments of these sequences are hypotheses that allow us to infer phylogenetic relationships among a set of species. Correct alignment is essential for the reconstruction and recovery of phylogenetic signals leading to a correct evolutionary hypothesis. The alignment of many genes with abundant phylogenetic information, such as 16S rRNA, becomes difficult by the presence of insertion and deletion events which increase in number with the inclusion of more divergent species, making the alignment ambiguous (Lydeard et al. 2000). These difficulties can be overcome by using additional information, such as the secondary structure of rRNA. Ribosomal RNA sequences form complex secondary structures based on complementarity of the bases along the molecule (Lydeard et al. 2002). Most models of known secondary structure of rRNA have been determined by comparative sequence analysis (Woese et al. 1980; Noller et al. 1981; Gutell et al. 1994).

The molecule of the large subunit rRNA (LSU rRNA or 16S RNA) can be divided in the 5' and 3' sections, each with three main structural domains (labeled I-VI) (Gutell et al. 2002) and in turn the stems are listed with letters and numbers (Wuyts et al. 2001). Several studies have shown the phylogenetic value of the rRNA secondary structure (Titus & Frost 1996; Lydeard et al. 2000; 2002), one of the most significant being the absence or reduction of three regions of the 16S rRNA for all Heterobranchia (Lydeard et al. 2000; 2002). These regions include a stem of domain II, the entire domain III (reduced to a single stem in some mollusks) and part of a stem in Domain V (G16) (Lydeard et al. 2002).

Heterobranchia is one of the main clades of gastropods, containing the largest number of species, which includes Pulmonata, Opisthobranchia and the Lower Heterobranchia (Bouchet & Rocroi, 2005). The Family Orthalicidae (Heterobranchia: Pulmonata: Stylommatophora) is the most diverse group of endemic land snails from Peru and South America. Other genera of the superfamily Orthalicoidea are also found in Oceania and Africa (Herbert & Mitchell 2009). Based on the 16S rRNA mitochondrial marker, Ramirez et al. (2009) found this family to be a monophyletic group,of the "non-achatinoid clade" within a global phylogeny of Stylommatophora, demonstrating the efficiency of this marker to resolve evolutionary relationships.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the utility of the information provided by the secondary structure to improve the alignments of the 16S rRNA gene in several species of land snails of the family Orthalicidae.

Materials and methods

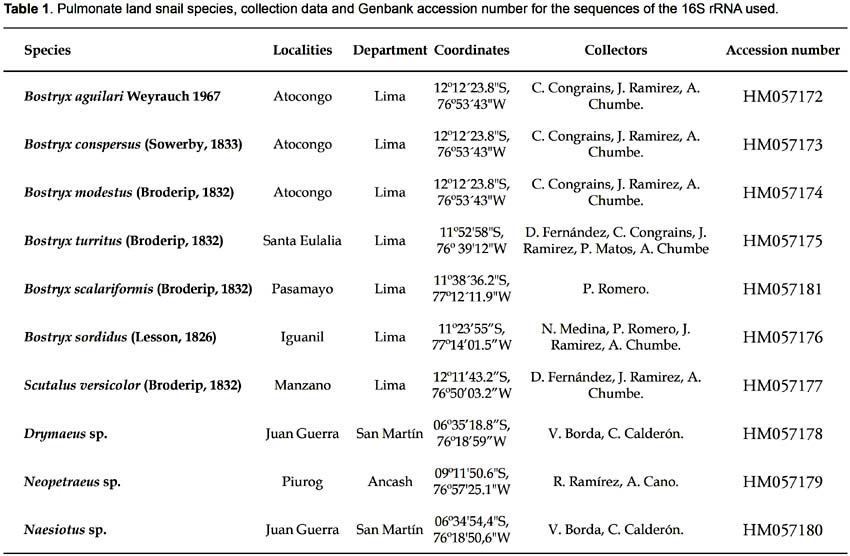

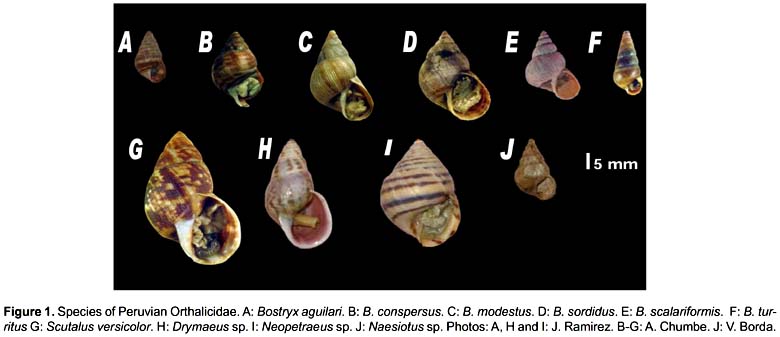

We used 10 species of the family Orthalicidae (belonging to five different genera) from different ecosystems of Peru (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Voucher specimens are deposited in the scientific collections of the Natural History Museum of San Marcos University. DNA was isolated by a modified CTAB method (Doyle & Doyle 1987; Ramírez 2004). Amplification was carried out using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Saiki et al. 1988). Primers developed by Ramírez (2004) were used for amplification of a segment of the 16S rRNA gene: 16SF-104 (5'-GACTGTGCTAAGGTAGCATAAT-3') and 16SR-472 (5'-TCGTAGTCCAACATCGAGGTCA-3'). The PCR products were purified and sequenced for both strands using the commercial services of MACROGEN USA (www.macrogen.com).

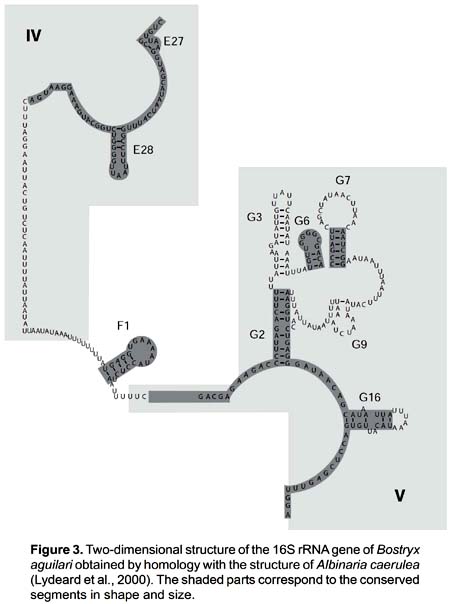

The sequences obtained were edited and proofread using chromatograms with Chromas (McCarthy, 1996). Consensus sequences were obtained with CAP3WIN (Huang & Madan, 1999). Sequences were deposited in GenBank (Accession numbers HM057172-HM057181). Global alignment was carried out with ClustalX 2.0 (Larkin et al. 2007). The alignment was corrected using as template the secondary structure of the 16S rRNA of Albinaria caerulea (Pulmonata: Clausiliidae) (Lydeard et al. 2000). We employed the DCSE format, which incorporates special symbols indicating the secondary structure in an RNA sequence alignment (De Rijk & De Wachter, 1993) in a text editor. We checked the formation of each of the stems by homology between the template and the other sequences in the alignment. The structure was plotted using the program RnaViz 2.0 (http://rnaviz.sourceforge.net) (De Rijk et al. 2003).

Results

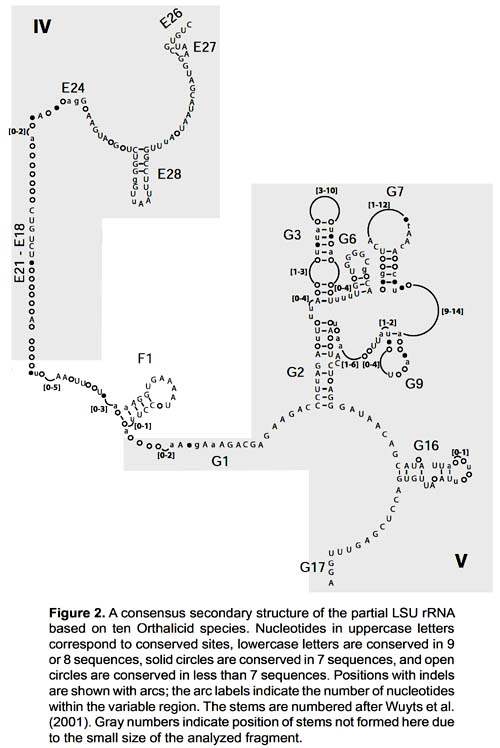

The sequences obtained ranged from 323 to 345 base pairs and the alignment had 373 positions. It corresponds to part of domains IV and V of the 3' end of the 16S rRNA gene (position 557 - 873 in the Albinaria caerulea sequence), including stems E27, E28, F1, G2, G3, G6, G7, G9 and G16. Stems E26, E24, E21, E18, G1 and G17 did not form due to the small size of the fragment analyzed (Fig. 2).

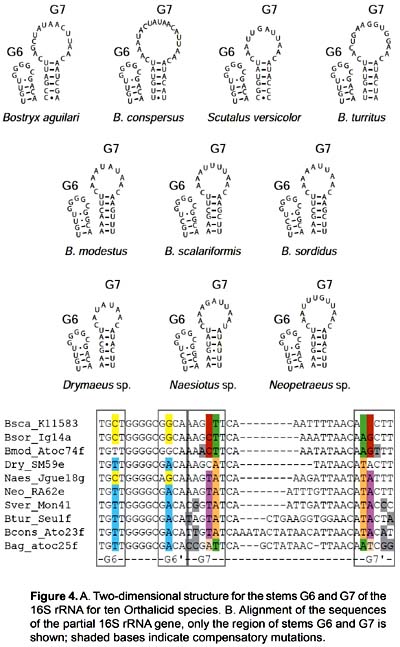

The secondary structure was recovered by homology for the 10 species studied (Fig. 2). The structure of the partial 16S rRNA sequence of B. aguilari is shown in Figure 3. Most of the stems are preserved and in general the loops are more variable (Figs. 2 and 3). The more conserved stems were E27 and E28. Stems F1, G2, G6, G7, G9 and G16 were variable but kept their size and shape; these stems present the phenomenon of compensatory mutations, and form the main phylogenetic information of this gene (Fig. 4). Stem G3 and its loop were extremely variable, with numerous unconventional bonds and variation in loop size from 2 to 10 bases. The loops formed by stems E28 and F1 showed minimal variation (one base) in the sequence. Loop G6 was preserved while loop G7 showed variation of 9 to 19 bases. Stem G16 (which is small in Heterobranchia) showed a 23-24 bases size with great variability in the area of the loop.

Discussion

The importance of alignment in phylogenetic reconstruction has been highlighted by various authors (Gatesy et al. 1993; Kjer 1995; Hickson et al. 1996). The use of information provided by the secondary structure of rRNA, combined with bioinformatic packages, results in better recovery of the phylogenetic signal compared with the alignments obtained only by bioinformatic programs (Titus & Frost, 1996). We reached the same conclusions in our analysis for Orthalicidae land snails.

During the evolution of rRNA, due to its function, its structure is more conservative than the sequence itself (Gutell et al. 1994). Compensatory mutations in stems are related to the maintenance of the structure. In contrast, the unpaired regions depend specifically on its sequence, making them more difficult to accept mutations (Smit et al. 2007). It is true that highly conserved regions tend to be unpaired, but unpaired regions are not always conserved; in eukaryotic rRNA, loops evolve faster than stems (Smit et al. 2007). This same pattern was observed for the 16S rRNA gene in our analysis for Orthalicidae land snails.

Despite using the secondary structure as a guide for alignment, stem G3 was extremely variable, complicating the alignment. Studying different taxa of molluscs, Lydeard et al. (2000) showed a variation from 8 to 96 bases in this stem. This would demonstrate heterogeneity between rates of evolution of different structures (stems, loops, bulges, etc.) (Smit et al. 2007).

Absence of a bulge-stem-loop in stem G16 (domain V) is a synapomorphy for all Heterobranchia, with a reduced stem size of 20 to 30 bases, while stem size for the rest of mollusks is 41 to 43 bases. This indel has been reported previously in phylogenetic studies (Thollesson 1999, Lydeard et al. 2000). Absence of this bulge-stem-loop in the G16 stem placed Orthalicidae within Heterobranchia, consistent with the current classification (Bouchet & Rocroi 2005). Loss and reduction of these structures explains why Heterobranchia have the shortest mitochondrial genome among the metazoans (Kurabayashi & Ueshima 2000).

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Chumbe, C. Congrains, D. Fernández, J. Chirinos, N. Medina, P. Matos, P. Romero, V. Borda and C. Calderón for assistance during laboratory and field work. We are grateful to P. Ramírez for his molecular logistic help and to E. Cano for his logistic help in Ancash. This study is part of Project 061001071 funded by Vicerrectorado de Investigación de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (VRI). Field work in San Martín was carried out as part of Project PEM2007B28 (VRI) and in Ancash with Project 051001041 (VRI). Dr. Lamas provided critical comments that helped to improve the final version of the manuscript.

Literatura cited

Bouchet P. & J. Rocroi. 2005. Classification and Nomenclator of Gastropod Families. Malacologia 47 (1-2): 1-397.

De Rijk P. & R. De Wachter. 1993. DCSE, an interactive tool for sequence alignment and secondary structure research. Computer Applications in the Biosciences 9: 735-740.

De Rijk P., J. Wuyts & R. De Wachter. 2003. RnaViz2: an improved representation of RNA secondary structure. Bioinformatics 19(2): 299-300.

Doyle J.J. & J.L. Doyle. 1987. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small amounts of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochemical Bulletin 19: 11-15.

Gatesy J., R. Desalle & W. Wheeler. 1993. Alignment-ambiguous nucleotide sites and the exclusion of systematic data. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 2: 152-157.

Gutell R., N. Larsen & C. Woese. 1994. Lessons from an evolving rRNA: 16S and 23S rRNA structures from a comparative perspective. Microbiological Reviews 58: 10-26.

Gutell R., J. Lee & J. Cannone. 2002. The accuracy of ribosomal RNA comparative structure models. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 12, 301-310.

Herbert D & A. Mitchell. 2009. Phylogenetic relationships of the enigmatic land snail genus Prestonella: the missing African element in the Gondwanan superfamily Orthalicoidea (Mollusca: Stylommatophora). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society Lond 96: 203-221.

Hickson R., C. Simon, A. Cooper, et al. 1996. Conserved sequence motifs, alignment, and secondary structure for the third domain of animal 12S rRNA. Molecular Biology and Evolution 13: 150-169.

Huang X. & A. Madan. 1999. CAP3: A DNA Sequence Assembly Program. Genome Research 9: 868-877.

Kjer K. 1995. Use of rRNA secondary structure in phylogenetic studies to identify homologous positions: An example of alignment and data presentation from the frogs. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 4: 314-330.

Kurabayashi A. & R. Ueshima. 2000. Complete sequence of the mitochondrial DNA of the primitive opisthobranch Pupa strigosa: systematic implication of the genome organization. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 17: 266-277.

Larkin M., G. Blackshields, N. Brown, et al. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23, 2947-2948.

Lydeard C., W. Holznagel, M. Schnare & R. Gutell. 2000. Phylogenetic analysis of molluscan mitochondrial LSU rDNA sequences and secondary structures. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 15: 83-102.

Lydeard C., W. Holznagel, R. Ueshima & A. Kurabayashi. 2002. Systematic implications of extreme loss or reduction of mitochondrial LSU rRNA helical-loop structures in gastropods. Malacologia 44: 349-352.

McCarthy, C. 1996. Chromas: version 1.3. Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia.

Noller H., J. Kop, V. Wheaton, et al. 1981. Secondary structure model for 23S ribosomal RNA. Nucleic Acids Research 9: 6167-6189.

Ramirez J., R. Ramírez, P. Romero, et al. 2009. Posición evolutiva de caracoles terrestres peruanos (Orthalicidae) entre los Stylommatophora (Mollusca: Gastropoda). Revista Peruana de Biología 16(1), 051-056.

Ramírez R. 2004. Sistemática e Filogeografia dos Moluscos do Ecossistema de "Lomas" do Deserto da Costa Central do Peru. Tese de Doutorado em Zoologia. PUCRS, Brasil.

Saiki R., D. Gelfand, S. Stoffel, et al. 1988. Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science 239: 487-91.

Smit S., J. Widmann & R. Knight. 2007. Evolutionary rates vary among rRNA structural elements. Nucleic Acids Research 35: 3339-3354.

Thollesson M. 1999. Phylogenetic analysis of Euthyneura (Gastropoda) by means of the 16S rRNA gene: use of a `fast' gene for `higher-level' phylogenies. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B 266: 75-83.

Titus T. & D. Frost. 1996. Molecular homology assessment and phylogeny in the lizard family Opluridae (Squamata: Iguania). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 6: 49-62.

Woese C., L. Magrum, R. Gupta, et al. 1980. Secondary structure model for bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA: Phylogenetic, enzymatic and chemical evidence. Nucleic Acids Research 8: 2275-2293.

Wuyts J., P. De Rijk, Y. Van de Peer, et al. 2001. The European large subunit ribosomal RNA database. Nucleic Acids Research 29, 175-177.

Trabajo presentado a la XVIII Reunión Científica del Instituto de Investigaciones en Ciencias Biológicas Antonio Raimondi, 200 años del nacimiento de Charles Darwin y el 150 aniversario de la publicación de On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. Del 19 al 21 de agosto de 2009.

Publicado impreso: 20/10/2010

Publicado online: 29/09/2010