Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO  uBio

uBio

Compartir

Revista Peruana de Biología

versión On-line ISSN 1727-9933

Rev. peru biol. vol.22 no.1 Lima 2015

TRABAJOS ORIGINALES

New mammalian records in the Parque Nacional Cerros de Amotape, northwestern Peru

Nuevos registros de mamíferos en el Parque Nacional Cerros de Amotape, noroeste de Perú

Cindy M. Hurtado1; Víctor Pacheco1,2

1 Museo de Historia Natural, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Apartado 14-0434, Lima-14, Perú.

2 Instituto de Ciencias Biológicas "Antonio Raimondi", Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Perú.

Abstract

The Pacific Tropical Rainforest and Equatorial Dry Forest are found only in southern Ecuador and northern Peru, and are among the most poorly known ecosystems of South America. Even though these forests are protected in Parque Nacional Cerros de Amotape (PNCA), they are threatened by fragmentation because of farming and agriculture. The aim of this study was to determine the medium and large mammalian species richness, using transect census, camera trapping, and specimen bone collection. Nine transects were established and 21 camera trap stations were placed along 16 km2 in three localities of PNCA, from August 2012 to April 2013. Total sampling effort was 215 km of transects and 4077 camera-days. We documented 22 species; including 17 with camera trapping, 11 with transect census, and 10 with specimen collection. Camera traps were the most effective method, and four species (Dasyprocta punctata, Cuniculus paca, Leopardus wiedii and Puma concolor) were documented only with this method. This comprised the first Peruvian record for Dasyprocta punctata, and the first record for the western slope of the Peruvian Andes for Cuniculus paca. Also, both specimen collections and sightings confirm the presence of Potos flavus, first record in the western slope of the Peruvian Andes. Panthera onca, Tremarctos ornatus and Saimiri sciureus are considered locally extinct, while several species are in need of further research. We highlight the importance of the high diversity of this rainforests and encourage local authorities to give the area the highest priority in conservation.

Key words: Pacific Tropical Rainforest, Equatorial Dry Forest, mammals, camera trapping, transect census.

Resumen

El Bosque Tropical de Pacífico y el Bosque Seco Ecuatorial, solo se encuentran desde el Sur de Ecuador hasta el Norte de Perú y están dentro de los ecosistemas más pobremente estudiados de Sudamérica. A pesar que estos bosques se encuentran protegidos dentro del Parque Nacional Cerros de Amotape (PNCA), están amenazados por fragmentación de hábitat debido a la agricultura y la ganadería. El objetivo de esta investigación fue determinar la riqueza de mamíferos medianos y grandes utilizando censos por transecto, cámaras trampa y colecta de especímenes. Se establecieron nueve transectos y se colocaron 21 estaciones con cámaras trampa en tres localidades del PNCA (16 km2) de agosto del 2012 a abril del 2013. El esfuerzo de muestreo acumulado fue 215 km de censos por transecto y 4077 cámara-días. Registramos 22 especies de mamíferos, 17 registradas con cámaras trampa, 11 con censos por transecto y diez con colecta de especímenes. El uso de cámaras trampa fue el método más efectivo y cuatro especies (Dasyprocta punctata, Cuniculus paca, Leopardus wiedii y Puma concolor) fueron registradas únicamente con este método. El registro de Dasyprocta punctata, es el primero para Perú y Cuniculus paca, el primer registro para la vertiente occidental de los Andes peruanos. Además, con avistamientos y colecta de especímenes se confirmó la presencia de Potos flavus para el PNCA siendo también el primer registro para la vertiente occidental de los Andes peruanos. A Panthera onca, Tremarctos ornatus y Saimiri sciureus se les considera localmente extintos, mientras que varias especies más necesitan mayor investigación para confirmar su presencia. Se resalta la importancia y alta diversidad de estos bosques y se recomienda a las autoridades locales darle prioridad en conservación.

Palabras clave: Bosque Tropical del Pacífico, Bosque Seco Ecuatorial, mamíferos, cámaras trampa, censos por transecto.

Introduction

Peru holds at least 508 species of mammals in eleven ecoregions (Pacheco et al. 2009). Although several inventories documented the mammal fauna of some Peruvian regions (Pearson 1951, 1957, Emmons 1984, Emmons et al. 1994, Solari et al. 2001, Emmons et al. 2001, Aquino et al. 2001, Solari et al. 2006, Pacheco et al. 2007, Pacheco et al. 2008, Tobler et al. 2008, Jiménez et al. 2010) the medium and large mammals of the northwestern region are known only by a few reports (Grimwood 1969, Pulido & Yockteng 1983, Encarnación & Cook 1998, INRENA 2000, 2005, Cossíos 2005, Alzamora 2005, Williams 2008). This issue may be attributed to the elusive behavior and nocturnal activity patterns of most mammalian species, and the high cost of appropriate equipment and methods for monitoring medium and large mammals such as camera trapping or genetic sampling (Kelly et al. 2011, MacKay et al. 2008).

The Parque Nacional Cerros de Amotape (PNCA) is located in the Tumbes Province, northwestern Peru, and has two distinct ecoregions; the Pacific Tropical Rainforest (hereafter PTR) and de Equatorial Dry Forest (hereafter EDF) (Brack-Egg 1986). The PTR holds high tropical diversity, similar to Eastern Amazonia and Central America (Lamas 1976, Cabrera & Willink 1980, Brack-Egg 1986, Morrone 2006), whereas the EDF has high diversity and endemism from different taxonomic groups (Best & Kessler 1995, Linares-Palomino et al. 2010, 2011). These forest types are extremely important and because of their restricted distribution, they exhibit high endemism (Sagastegui et al. 1999, Aguilar 1994) and poorly known species, and are recognized as world hotspots (Mittermeier et al. 2005, Olson & Dinerstein 2002). Furthermore, this area is losing connectivity from the Ecuadorian forest because of deforestation for farming and agriculture, causing numerous local extinctions (Dodson & Gentry 1991, Wunder 2001).

Most mammalian research at PNCA has been focused on bats (Pacheco et al. 2007) and primates with a few reports on medium- and large-sized mammals (Encarnación & Cook 1998). Grimwood (1969) collected mammalian information across Peru and registered 17 medium- and large-sized mammals for Tumbes. Pulido and Yockteng (1983) registered in PNCA 24 species but only 7 of them were recorded by direct observation and the other 17 through interviews. Encarnación and Cook (1998) registered 17 mammals by direct observations and 2 by indirect evidence. In 2000, PNCA managers compiled a list of 29 mammals for the area based on interviews (INRENA, 2000) and Pacheco et al. (2009) who compiled a list of all mammals found in Peru mentioned just 17 medium and large mammal species for the PTR.

The aim of this study was to determine the medium and large mammalian richness in the PNCA using a combination of traditional methods such as transect censuses, and specimen bone collection with camera trapping . Also, we reviewed previous species lists to confirm, add and discuss the occurrence of mammals in the area. This survey was carried out for 8 months, covering part of the PTR and EDF and the dry and rainy seasons. Also, we provide recommendations to park managers in order to focus conservation efforts in certain areas and species of the national park.

Materials and methods

Study area

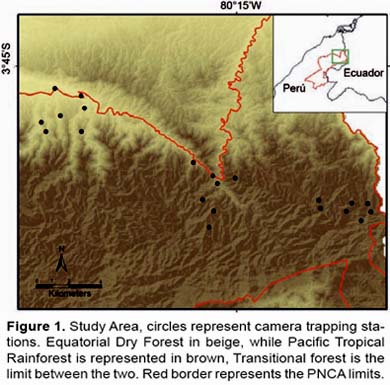

The PNCA is located in the northeastern region of Tumbes Province, Peru (03°50’S – 80°16’W). Three major forest types can be distinguished in the study area: Equatorial Dry Forest, Pacific Tropical Rainforest, and a transitional forest; one locality per forest type was selected. The temperature is above 24°C throughout the year and the annual mean precipitation is about 610.9 mm (Cadenillas 2010).

La Angostura, 100 – 350 m (03°42’S – 80°23’W): Equatorial Dry Forest with a predominance of Prosopis pallida, Acacia macracantha on lower areas, and Ceiba trichistandra, Cordia lutea and Loxopterygium huasango on hillsides (Pacheco et al. 2007).

El Caucho, 350 – 600 m (03°50’S – 80°16’W): Transitional forest between the Equatorial Dry Forest of La Angostura and the Pacific Tropical Rainforest of Campo Verde. It is dominated by Ceiba trischistandra, Cavanillesia platanifolia, Ficus jacobii, Triplaris cumingiana, Bougainvillea peruviana, Tessaria integrifolia, Inga feuillei, and Cecropia peltata (Ponte 1998, Pacheco et al. 2007).

Campo Verde, 600 – 850 m (03°50’S – 80°10’W): Pacific Tropical Rainforest, dense with rough topography and high humidity. Dominated by Centrolobium ochroxylum, Cordia eriostigma, Tabebuia chrysantha, Triplaris cumingiana, Gallesia integrifolia, Ficus jacobii, and Cedrela fissilis (Ponte 1998, Pacheco et al. 2007).

Sampling techniques

Camera trapping: a set of 21 unbaited camera trap stations were placed from September to December of 2012 (dry season) and from January to April 2013 (rainy season), with seven camera stations per type of forest that run continuously during the entire survey period. Each station had one camera trap (Bushnell trophy cam-standard edition) set along animal trails, into the woods or near a stream or water source. Also each camera trap was separated by at least 1 km, the minimum home range of the studied species (Fig. 1). Cameras were placed at an average height of 30 cm above ground (Kelly 2008) and set to take three photos at one-second intervals after each detection. Hence an area of 16 km2 was covered with the three localities with 21 camera traps.

Transects censuses: three transects of 3 – 4 km were marked and set at each locality (nine transects in total). The transects were walked by one researcher and one local guide at approximately 1 to 1.5 km/hour, in the morning from 6:00 to 12:00 and at night from 18:00 to 22:00 (Peres & Cunha 2011). After each sighting the species name, time, number of individuals and GPS location were recorded. A total of 35 km were placed along the three localities. The dry season was surveyed from August to December 2012 while the rainy season from January to April of 2013.

Specimen collection: After each survey of either transect census or camera trapping the surroundings were searched for evidence of mammalian species. Skulls and other bones on the ground were collected in plastic bags and labeled with the date, time, GPS location and type of specimen. Later, the samples were washed and air-dry for proper identification at the Museo de Historia Natural of Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (Lima City, Peru).

Data analyses

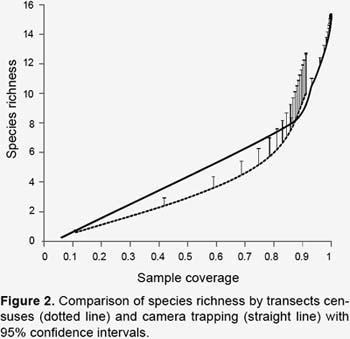

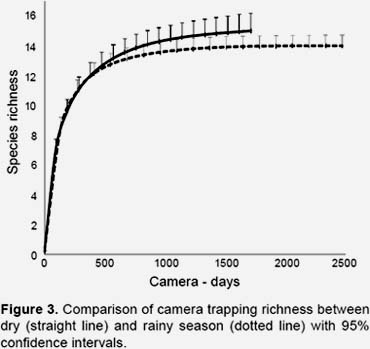

Each survey sample (transects and camera traps) was standardized by sampling completeness using the coverage-based rarefaction method proposed by Chao and Jost (2012), confidence intervals were obtained with 100 bootstraps. Accumulation curves were obtained from iNEXT (R package) (Chao & Jost 2012, Hsieh et al. 2013). The sampling unit for the transect census was the transect (76 in total) while for cameras was one night per camera (4077 in total), no extrapolation was needed. We compared our data with previous surveys at the study site (Pulido and Yockteng 1983, Encarnación and Cook 1998, and Pacheco and Cadenillas unpublished data) to complete and update the species list (Table 1).

We follow the nomenclature of Wilson and Reeder (2005), Pacheco et al. (2009) and recent changes found in de Vivo and Carmignotto (2015) and Patton and Emmons (2015).

Results

We registered 22 medium- and large-sized mammals in the three types of forest: 17 species in the Pacific Tropical Rainforest, 20 in the transitional forest, and 13 species in the Dry Forest (Table 1, Appendix). The coverage-based accumulation curve shows that camera trapping performed better than transect census obtaining 99.9% of sample completeness and almost 50% more species richness (Fig. 2). Transect censuses had a sample completeness of 91.2% registering only 11 species (Fig. 3).

Camera trapping

We obtained 1061 records of 17 medium- and large-sized mammals in 4077 camera days (Table 1). Simosciurus nebouxii (I. Geoffro St.-Hilaire, 1855) and Cebus albifrons (Humboldt, 1812) were the only two arboreal species registered and these were excluded from analysis because of difference in capture probabilities. Latency to initial detection (number of days needed for the first mammal detection) was seven camera-days for the dry season and 21 camera-days for the rainy season. The 15 species were registered during the first 53 days or 984 camera-days (Fig. 3).

Transect census

After 215 km of diurnal and nocturnal census transects, 45 independent records of 11 medium and large mammals were obtained (Table 1). The most registered species with this method was Mazama americana (Erxleben, 1777) with 15 sightings, followed by the primates Alouatta palliata (Gray, 1849) with 11 sightings, and Cebus albifrons with six. Pecari tajacu (Linnaeus, 1758) had only five sightings while Tamandua mexicana (Saussure, 1860) and Dasypus novemcinctus Linnaeus, 1758 only two. The other seven species were represented only by a single sighting during the whole study period (Table 1).

Specimen collection

In total, 29 specimens of 10 medium-sized mammals were collected and deposited at the Museo de Historia Natural of Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, MUSM (Table 1). The identification of these specimens was confirmed with museum vouchers. The species recorded were Potos flavus (Schreber, 1774) which was previously sighted in 2005 (V. Pacheco pers. obs.); Choloepus hoffmanni Peters, 1858 and Didelphis marsupialis Linnaeus, 1758 reported previously by interviews from Pulido and Yockteng (1983); and, Leopardus pardalis, Alouatta palliata, Cebus albifrons, Nasua nasua, Procyon cancrivorus, Mazama americana and Pecari tajacu previously registered by direct observation in 1994 (Encarnación & Cook 1998).

New records

In this study we report the presence of three new species for the area and the western slope of the Peruvian Andes. Cuniculus paca was only registered by camera trapping in the transitional forest and Pacific Tropical Rainforest (3°51'13"S, 80°16'3.20"W). Also, camera traps registered Dasyprocta punctata, first record for Peru, found in the Pacific Tropical Rainforest (3°51'13"S, 80°16'3.20"W) and identified by its coloration patterns and distribution range (Patton & Emmons 2015). Potos flavus was confirmed in the area by a complete skeleton found in the transitional forest (3°49'44"S, 80°15'34.85"W) (Table 1).

Discussion

Species richness

We report 22 species of medium- and large-sized mammals in PNCA using three sampling methods, confirming that multiple non-invasive methodologies are required to register the complete mammalian fauna (Gompper et al. 2006). Camera trapping was more effective at registering several medium and large cryptic carnivores (Fig. 2), confirming reports of previous surveys (Silveira et al. 2003, Tobler et al. 2008, Jiménez et al. 2010). On the other hand, transect censuses were better at registering arboreal species such as A. palliatta, C. albifrons, and S. nebouxii (Table 1). Also, specimen collection was extremely helpful in registering arboreal and nocturnal species as P. flavus, as well as silent species as C. hoffmanni.

From previous inventories, Pulido and Yockteng (1983) registered 24 species for the PNCA based mainly on interviews (Table 1). Compared to them we found no evidence of seven species: Bradypus variegatus Schinz 1825, Cyclopes didactylus (Linnaeus 1758), Tamandua tetradactyla (Linnaeus 1758), Coendou bicolor (Tschudi 1844), Sylvilagus brasiliensis (Linnaeus 1758), Leopardus colocolo (Molina 1782), and Panthera onca (Linnaeus 1758). Encarnación & Cook (1998) registered 17 species by sightings and tracks. From their list we did not find any evidence of T. tetradactyla which was registered by observation; Saimiri sciureus (Linnaeus 1758) that was registered by observation nor Tremarctos ornatus (F. G. Cuvier 1825) registered by track (Table 1).

Tamandua tetradactyla, registered by interviews (Pulido & Yockteng 1983) and sightings (Encarnación & Cook 1998), was probably mistaken with Tamandua mexicana (Saussure 1860). The fur color pattern of T. tetradactyla may vary along its distribution, at times not showing the black vest found in T. mexicana (Wetzel 1975, Eisenberg & Redford 1989). At present, T. tetradactyla is only found in the eastern slope of the Andes (Eisenberg & Redford 1989, Gardner 2007, Hayssen 2011). According to Gardner (2007), the subspecies found in Tumbes is T. m. punensis J. A. Allen, 1916.

In need of research

The arboreal Bradypus variegatus, Cyclopes didactylus and Coendou bicolor previously registered by Pulido and Yockteng (1983) are cryptic arboreal species. In consequence, to confirm its presence a species-specific research needs to be developed.

Sylvilagus brasiliensis, also registered by Pulido and Yockteng (1983), could have been mistaken with Dasyprocta punctata because some local people in Ecuador (Tirira 2007), and people from Tumbes as well, call it "conejo" (rabbit in Spanish), which also is the common name for S. brasiliensis . Nonetheless, further research needs to be carried out in order to confirm the species in the area.

The pampas cat (Leopardus colocolo) likely is present in the area, as it was reported in Tumbes by Grimwood (1969), and has a wide distribution range from sea level (García-Olaechea et al. 2013) to 4982 m in the Andes (Cossíos et al. 2007). In the Lambayeque Equatorial Dry Forest, south of our study site, this species relative abundance is about 22.1 (number of photographs/1000 camera-days), while Leopardus pardalis (Linnaeus 1758), is considered rare with much lower relative abundance 0.7 (number of photographs/1000 camera-days) (A. García-Olaechea pers. com.). This pattern in the adjacent forest suggests that there may be some competition between these two small cats. In our study area we registered the small cats, L. pardalis and L. wiedii (Schinz 1821) which may limit the abundance of L. colocolo. Still, more survey effort needs to be obtained to confirm its presence.

One individual of Puma yagouaroundi (É. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire 1803) was seen by one researcher in an expedition in 2004 (V. Pacheco pers. obs.). Nonetheless, we could not get any photograph of this species with camera trapping what suggests that this might be a rare species in the area.

Local extinctions

The jaguar (Panthera onca) has been registered in Tumbes by several authors (Grimwood 1969, Pulido & Yockteng 1983, INRENA 2000), was often sighted in the PNCA, and reports of cattle killing were made by local peasants (Rodríguez 1998, INRENA 2000). However, at present there is no confirmed evidence of its presence. Local farmers are familiar with these animals but believe that they are no longer present. We agree with this statement due to the fact that jaguars when present are usually registered in camera photos, even with low capture frequency (Wallace et al. 2003, Maffei et al. 2004, Tobler et al. 2013), because they usually use trails (Maffei et al. 2004, Harmsen et al. 2010), where some cameras were located. Moreover, world jaguar distribution surveys from 1999 (Sanderson et al. 2002, Zeller 2007, Zeller et al. 2011) showed that the Tumbes population was left isolated from the remaining populations with the closest being found in Peru and Ecuador east of the Andes. In this scenario the possibility of a remaining population of jaguars in the area is scarce.

Another species that might have suffered the same fate is the Andean bear (Tremarctos ornatus). This species was found in previous reports for the Parque Nacional Cerros de Amotape (Encarnación & Cook 1998, Maravi et al. 2003) contrary to some authors that considered Tumbes as its historic distribution (Peyton 1999, Garcia-Rangel 2012, Wallace et al. 2014). Unfortunately, new records are lacking even though local people remember its presence; the last record we could obtain by interviews was around 1994 from a footprint near the Ecuadorian border, sighted by one of our local guides.

The squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciureus) is known to be distributed in Ecuador, Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil and Guyanas, always in the east side of the Andes (Cabrera 1957, Hershkovitz 1977, Boinski & Cropp 1999), except the single record from Tumbes on the western slope of the Andes, based on a sighting of Encarnación and Cook (1998) of a mixed troop with Cebus albifrons (Encarnación & Cook 1998). Until 2011 there had been at least two undergraduate theses (Alzamora 2005, M. Sánchez pers. com.) involving long-term census of Alouatta palliata, as well as field expeditions in 2004-2005 (V. Pacheco pers. com), with no more evidence of S. sciureus. Although we had several encounters with C. albifrons and A. palliata from September 2011 through May 2013 we found no further evidence of its presence.

Based on the above evidence, we suggest that these three species; Panthera onca, Tremarctos ornatus and Saimiri sciureus should be considered locally extinct.

New Records

In this study we verified the presence of four species of mammals previously reported by indirect evidence; Didelphis marsupialis, Choloepus hoffmanni, Lycalopex sechurae (Pulido & Yockteng 1983) and Puma concolor (Pulido & Yockteng 1983, Encarnación & Cook 1998, Table 1). Also reported are Dasyprocta punctata, the first record for Peruvian fauna, and both Cuniculus paca and Potos flavus as first recordings for the western slope of the Peruvian Andes.

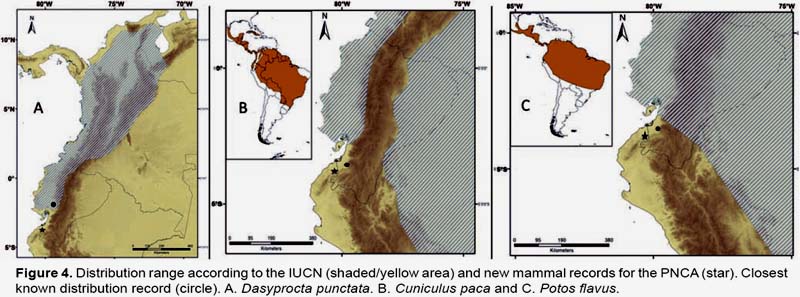

Dasyprocta punctata is distributed from northern Colombia to northwestern Venezuela, along the western coast of Colombian and Ecuadorian Pacific coast (Patton & Emmons 2015) with its southern limit range in San Jose, Ecuador (Patton & Emmons 2015). Based on our photographic records, the known distribution of this species is extended by 205 km South to Las Pavas locality (3°51'13"S, 80°16'3.20"W), northeastern Peru (Fig. 4A). The subspecies found in the study area would correspond to Dasyprocta punctata chocoensis (Cabrera 1957), but direct examination of vouchers is required to confirm determination.

Cuniculus paca is found from lowland rainforests from Mexico, along Central America through Paraguay (Perez 1992, Patton & Emmons 2015). Its western distribution was known to occur to southern Ecuador (Patton & Emmons 2015). Currently, the species is known in Peru only in the eastern side of the Andes (Pacheco et al. 2009). Based on photographs, we present the first record for the western side of the Peruvian Andes, 70 km west of the closest locality known, Portovelo, Ecuador (AMNH 46547) (Figure 4B).

Potos flavus is distributed from Mexico, through Central America and south to Bolivia and Brazil (Ford & Hoffmann 1988, Emmons & Feer 1997, Kays et al. 2008); on the western Andes it is known to occur until Zaruma, southern Ecuador (AMNH 46513). Based on one full skeleton, collected specimen and previous sightings, we extend its distribution range to La Union locality (3°49'44"S, 80°15'34.85"W) northern Peru by 72 km, which constitutes the first record in the western slope of the Peruvian Andes (Figure 4C).

Because these three species (Dasyprocta punctata, Cuniculus paca and Potos flavus) were found only in the transitional forest and Pacific Tropical Rainforest we believe that PNCA likely is the southern limit of their distribution; further south the area becomes dryer and more open and less suitable for these species.

Conservation

PNCA is an area of unique diversity but also of great concern because several species are listed as threatened or endangered. The primates found in the area are at risk of extinction, especially C. albifrons aequatorialis J. A. Allen, 1914 which is considered Critically Endangered by the IUCN (2008). Also, A. palliatta aequatorialis Festa, 1903 is listed as Vulnerable. Furthermore PNCA holds two species in Data Deficient category; Lontra longicaudis (Olfers, 1818) and Mazama americana (Table 1). Even though Nasua nasua is listed as low concern, in Tumbes we believe it should be categorized as Data Deficient or Vulnerable because local people hunt males for their bacula which is erroneously thought to increase sexual properties in men. Cook and Encarnación (1994) informed that this practice was common not only with Nasua nasua but with Eira barbara for the same purposes. Additionally, some people not familiar with the species also hunt Procyon cancrivorus. The baculum is sold in the markets for about $300 (A. García pers. com).

Furthermore, the fact that at least three species are now considered locally extinct may indicate that the area of PNCA is insufficient to hold large carnivores. Nonetheless, in other protected areas in the USA, extinction rate is highly correlated with the density of human population in the surrounding areas (Parks & Harcourt 2002). The effect that roads and anthropogenic disturbances cause in wildlife extinction may be greater that the size of the natural protected area (Parks & Harcourt 2002). This statement is relevant to the PNCA, since we found that the buffer area, comprised of dry forest and transitional forest, was greatly impacted by anthropogenic activities such as farming and agriculture (we documented high capture rate of cattle in camera trapping).

We also registered a full skeleton of Leopardus pardalis poisoned by farmers because it preyed on their poultry; this confirms human-carnivore conflicts, also expressed in interviews. This small cat feeds on chicken and eggs causing monetary losses for farmers who end up killing them. Furthermore, illegal boulder extraction is being carried out within the limits of the national park; altering the course of streams or disperses them among multiple channels, making them almost nonexistent. Several photographs of dogs and hunters were obtained which suggests that hunting for bush meat (Mazama americana and Pecari tajacu) is fairly common. The presence of people resulted in the theft of three camera traps, later replaced to continue the study. Also, illegal logging is common and hard to control by park guards because of limited personnel. As result, this rainforest is losing its connectivity with the forest in Ecuador (see Hansen et al. 2013). The area of Campo Verde should be one of the better protected parts of the National Park; it holds great diversity and is threatened by locals and foreigners. In summary, a lot of conservation work is needed in PNCA. An effective management plan should be developed by administrators of the park in association with the Academia and local people.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Rufford Small Grant for funding and Idea Wild for equipment funding. Also we are grateful to Ruben Martínez and Liliana Reaño who gave the authorization and support for this research. We also thank Alan García Cruz and the volunteers: Jaime Pacheco, Cynthia Musaja and Jesus Muñoz for the incredible fieldwork support. Also we would like to thank Marcella Kelly, Sergio Nolazco, Mabel Sánchez, Carlos Jiménez, and Edith Salas for advice in methodological techniques; as well as, Alvaro García Olaechea, Jose Serrano, and Natalí Hurtado for reviewing this manuscript.

Literature cited

Aguilar P. 1994. Características faunísticas del norte del Perú. Arnaldoa 2(1):77-102.

Alzamora M. 2005. Población y hábitos alimentarios de Alouatta palliata aequatorialis (Gray, 1849)"Mono Coto de Tumbes" en la zona reservada de Tumbes. Sector las pavas- La Unión. Tesis para optar al título profesional de biólogo. Universidad Nacional de Piura. 48pp. Piura.

Aquino R., R.E. Bodmer & J.G. Gil. 2001. Mamíferos de la cuenca del río Samiria: Ecología poblacional y sustentabilidad de la caza. Impresión Rosegraf S.R.L., Lima.

Brack-Egg A. 1986. Las ecorregiones del Perú. Boletín de Lima 44:57-70.

Best B.J. & M. Kessler M. 1995. Biodiversity and Conservation in Tumbesian Ecuador and Peru. Pp.: 218 BirdLife I. BirdLife International, Wellbrook Court, Girton Road, Cambridge CB3 0NA, U.K.

Boinski S. & S. J. Cropp 1999. Disparate data sets resolve squirrel monkey (Saimiri) Taxonomy: Implications for behavioral ecology and biomedical usage. International Journal of Primatology 20(2):237-256. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1020522519946

Cabrera A. 1957. Catálogo de los Mamíferos de América del Sur. Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales "Bernardino Rivadavia" e Instituto Nacional de Investigación de las Ciencias Naturales. Editora Coni. Ciencias Zoologicas, Tomo 4, N° 1, 308 p. Buenos Aires.

Cabrera A. & A. Willink. 1980. Biogeografía de América Latina, 2nd edition. Serie Biología, Secretaria General de la Organización de los Estados Americanos, Washington D.C. 122pp.

Cadenillas R. 2010. Diversidad, ecología y análisis biogeográfico de los murciélagos del Parque Nacional Cerros de Amotape, Tumbes-Perú. Tesis de maestría. Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. 107pp.

Chao A. & L. Jost. 2012. Coverage-based rarefaction and extrapolation: standardizing samples by completeness rather than size. Ecology 93:2533-2547. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/111952.1

Cook G. & F. Encarnación. 1994. La fauna silvestre y sus hábitats en la zona reservada de Tumbes. Informe de Campo. INRENA.

Cossíos D. 2005. Dispersión y variación de la capacidad de germinación de semillas ingeridas por el zorro de costeño (Lycalopex sechurae) en el Santuario Histórico Bosque de Pomac, Lambayeque. Tésis para optar el grado académico de Magister en Zoología con mención en Ecología y Conservación. Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos.

Cossíos D., A. Madrid, J. Condori & U. Fajardo. 2007. Update on the distribution of the Andean cat Oreailurus jacobita and the pampas cat Lynchailurus colocolo in Peru. Endangered Species Research 3: 313-320. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3354/esr00059

de Vivo M. & A. P. Carmignotto. 2015. Family Sciuridae G. Fischer, 1817. In: J.L. Patton, U.F.J. Pardiñas, and G. D’Elía, eds. Mammals of South America. Volume 2, Rodents. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. Pp. 1-48.

Dodson C.H. & A.H. Gentry. 1991. Biological extinction in Western Ecuador. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 78:273-295. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2399563

Eisenberg J.F & K.H. Redford. 1989. Mammals of the Neotropics: the central Neotropics. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois. Vol. 3. 609 pp.

Emmons L. 1984. Geographic variation in Densities and Diversities of Non-Flying Mammals in Amazonia. Biotropica 16: 210-222. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2388054

Emmons L. & F. Feer. 1997. Neotropical rainforest mammals: a field guide. University of Chicago Press.

Emmons L., C. Ascorra, & M. Romo. 1994. Mammals of the río Heath and Peruvian pampas. En: R. Foster, J. Carry y A. Forsyth, eds. The Tambopata-Candamo Reserved Zone of southeastern Perú: A biological assessment RAP Working papers 6.Conservation International, Washington D.C. pp146-149.

Emmons L.H., L. Luna W. & M. Romo R. 2001. Mammals of the Northern Vilcabamba mountain range, Peru. In: L.E. Alonso, A. Alonso, T.S. Schulenberg & F. Dallmeier, eds. Biological and social assessments of the Cordillera de Vilcabamba, Peru. RAP Working Papers 12 & SI/MAB Series 6, Conservation International, Washington, D.C. Pp. 105-109, 255-257.

Encarnación F. & G. Cook. 1998. Primates of the Tropical Forest of the Pacific Coast of Peru: The Tumbes Reserved Zone. Primate Conservation 18:15-20.

Ford L. & R. Hoffmann. 1988. Potos flavus. Mammalian Species 321: 1-9.

García-Olaechea A., C. Chávez-Villavicencio & J. Novoa. 2013. Leopardus pajeros (Desmarest, 1816) (Carnivora: Felidae) in Northern Peru: first record for the department of Piura at the Mangroves San Pedro de Vice and geographic expansion. Check List 9(6): 1596–1599, 2013.

García-Rangel S. 2012. Andean bear Tremarctos ornatus natural history and conservation. Mammal Review 42(2), 85–119. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2907.2011.00207.x

Gardner A. L. 2007. Suborder Vermilingua. IN: Gardner, A.L. (Ed) Mammals of South America, Volume I. Marsupials, xenarthrans, shrews, and bats. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London. pp. 669.

Gompper M. E., R. W. Kays, J. C. Ray, S. D. Lapoint, D. A. Bogan & J. R. Cryan. 2006. A Comparison of Noninvasive Techniques to Survey Carnivore Communities in Northeastern North America. Wildlife Society Bulletin 34: 1142–1151. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2193/0091-7648

Grimwood I. R. 1969. Notes on the distribution and status of some Peruvian mammals. Special publication Nº 21. American committee for international wild life protection and New York Zoological Society. Bronx, NY.

Hansen M., P. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. Turubanova, A. Tykavina et al. 2013. High-Resolution Global Maps of 21-st Century Forest Cover Change. Science 342(6160):850-853. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1244693

Harmsen B. J., R. J. Foster, S. Silver, L. Ostro & C. P. Doncaster. 2010. Differential Use of Trails by Forest Mammals and the Implications for Camera-Trap Studies: A Case Study from Belize. Biotropica 42(1), 126–133. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7429.2009.00544.x

Hayssen V. 2011. Tamandua tetradactyla (Pilosa: Myrmecophagidae). Mammalian Species 43(1):64 – 74. doi: http://dx.doi.org/ http://dx.doi.org/10.1644/874.1

Hershkovitz P. 1977. Living New World Monkeys (Platyrrhini) with an Introduction to Primates, Vol.1. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Hsieh T. C., K. H. Ma & A. Chao. 2013. iNEXT online: interpolation and extrapolation (Version 1.3.0) [Software]. Available fromhttp://chao.stat.nthu.edu.tw/blog/software-download/.

INRENA. 2000. Estrategia de conservación y desarrollo sostenible de la Reserva de Biosfera del Noroeste 2001-2010.Instituto Nacional de Recursos Naturales. Tumbes-Perú. 93 pp.

INRENA. 2005. Expediente técnico de categorización de la Zona Reservada de Laquipampa, Refugio de Vida Silvestre Laquipampa.

IUCN. 2008. (On line). IUCN Red list of threatened species. Version 2014.3 <www.iucnredlist.org>. Access 10/07/2014.

Jiménez C., H. Quintana, V. Pacheco, D. Melton & G. Tello. 2010. Camera trap survey of medium and large mammals in a montane rainforest of northern Peru Evaluación de mamíferos medianos y grandes mediante trampas cámara en un bosque montano del norte del Perú. Revista peruana de Biología 17(2): 191–196. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/rpb.v17i2.27

Kays R., F. Reid, J. Schipper, & K. Helgen. 2008. Potos flavus. In: IUCN 2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 23 April 2014

Kelly M. J. 2008. Design, evaluate, refine: camera trap studies for elusive species. Animal Conservation 11(3): 182–184. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1795.2008.00179.x

Kelly M. J., J. Betsch, C. Wultsch, B. Mesa, & L. S. Mills. 2011. Noninvasive Sampling for carnivores. Pages 47- 69. In Boitani, L. & R. Powell, editors. Carnivore Ecology and Conservation. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Lamas G. 1976. Notas sobre mariposas peruanas (Lepidoptera). III. Sobre una colección efectuada en el departamento de Tumbes. Revista peruana de entomología 19(1): 8-12.

Linares-Palomino R., L. P. Kvist, Z. Aguirre-Mendoza, C. Gonzales-Inca. 2010. Diversity and endemism of woody plant species in the Equatorial Pacific Seasonally Dry Forests. Biodiversity and Conservation 19:169-185.

Linares-Palomino R., A.T. Oliveira-Filho, R.T. Pennington. 2011. Neotropical Seasonally Dry Forests: Diversity, Endemism and Biogeography of Woody Plants. In: Dirzo, R., Mooney, H., Ceballos, G., Young, H. (eds.). Seasonally Dry Tropical Forests: Ecology and Conservation. Island Press. Washington, DC 20009, USA. Pp. 3-21

MacKay P., W. J. Zielinski, R. A. Long & J. C. Ray. 2008. Noninvasive Research and Carnivore Conservation. In: Long R., P. MacKay, W. Zielinski & J. Ray, eds. Noninvasive survey Methods for Carnivores. Island Press, Washington. Pp. 1-7.

Maffei L., E. Cullar & A. Noss. 2004. One thousand jaguars (Panthera onca) in Bolivia’s Chaco? Camera trapping in the Kaa-Iya National Park. Journal of Zoology 262, 295–304. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0952836903004655

Maravi E., L. Norgrove, J. Amanzo & A. Sissa. 2003. The spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus) and the Mountain Tapir (Tapirus pinchaque) in the northern Andes Ecoregion-Peru subdivision: Preliminary identification of conservation priorities. WWF program office. 37pp.

Mittermeier R., P. Robles Gil, M. Hoffman, J. Pilgrim, et al. 2005. Hotspots revisited: Earth’s biologically richest and most threatened terrestrial ecoregions. Conservation International. Washington.

Morrone J. 2006. Biogeographic Areas and Transition Zones of Latin America and The Caribbean Islands Based on Panbiogeographic and Cladistic Analyses of The Entomofauna. Annual Review of Entomology 51: 467–494. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ento.50.071803.130447

Olson D., M. Dinerstein, E. 2002. The global 200: Priority ecoregions for global conservation. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 89: 125-126. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3298564

Pacheco V., R. Cadenillas, S. Velazco, et al. 2007. Noteworthy bat records from the Pacific Tropical rainforest region and adjacent dry forest in northwestern Peru. Acta Chiropterologica 9(2): 409-422. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3161/1733-5329(2007)9[409:NBRFTP]2.0.CO;2

Pacheco V., E. Salas, L. Cairampoma, et al. 2008. Contribución al conocimiento de la diversidad y conservación de los mamíferos en la cuenca del río Apurímac, Perú. Revista Peruana de Biología 14(2): 169-180.

Pacheco V., R. Cadenillas, E. Salas, C. Tello & H. Zeballos. 2009. Diversidad y endemismo de los mamíferos del Perú. Revista Peruana de Biología 16(1): 005-032. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/rpb.v16i1.111

Parks S. A. & A. H. Harcourt. 2002. Reserve Size, Local Human Density, and Mammalian Extinctions in U.S. Protected Areas. Conservation Biology 16: 800–808. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.2002.00288.x

Patton J. & L. H. Emmons. 2015. Family Dasyproctidae Bonaparte, 1838. In: J.L. Patton, U.F.J. Pardiñas, and G. D’Elía, eds. Mammals of South America. Volume 2, Rodents. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. Pp. 733-762.

Pearson O. P. 1951. Mammals in the Highlands of Southern Peru. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 106(3):115-174.

Pearson O. P. 1957. Additions to the mammalian fauna of Peru and notes on some other Peruvian mammals. Breviora 73: 1–7.

Peres C. A. & A. A. Cunha. 2011. Manual para censo e monitoramento de vertebrados de medio é grande porte por transecçao linear em florestas tropicais. Wildlife Technical Series, Wildlife Conservation Society, Brasil. 26pp.

Perez E. 1992. Agouti paca. Mammalian Species 404: 1-7

Peyton B. 1999. Spectacled Bear Conservation Action Plan. In: C. Servheen, S. Herrero & B. Peyton, eds. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan: Bears. IUCN/SSC Bear specialist Group. Pp. 157-198.

Ponte M. 1998. Inventario y análisis florístico de la estructura del bosque. In: Wust W. (Ed.). La Zona Reservada de Tumbes-biodiversidad y diagnóstico socioeconómico the John D. and Catherine C. MacArthur Foundation/Fondo Nacional por Las Áreas Protegidas por el estado (PROFONANPE), Lima. Pp. 43-65.

Pulido V. & C. Yockteng. 1983. Conservación de la fauna silvestre en el Bosque Nacional de Tumbes, con especial referencia al "coto mono". Symposio conservación y manejo de fauna silvestre neotropical. (IX CLAZ PERU): 33-43.

Rodríguez J. 1998. Mamíferos de la Zona Reservada de Tumbes.In:: Wust H.W. La Zona Reservada de Tumbes - Biodiversidad y Diagnóstico Socioeconómico. The John D. and Catherine C. MacArthur Foundation / Fondo Nacional por las Áreas Protegidas por el Estado (PROFONANPE). Lima, Perú, 188 pp.

Sagástegui A., M. O. Dillon, I. Sánchez, S. Leiva & P. Lezama. 1999. Diversidad Florística del Norte del Perú. Tomo I. Edit. Graficart, Trujillo. Pp. 221

Sanderson E.W., K. H. Redford, C. L. Chetkiewicz, R. Medellin, et al. 2002. Planning to save a species: the jaguar as a model. Conservation Biology 16: 58–72. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.2002.00352.x

Silveira L., A. T. Jácomo & J. A. Diniz-Filho. 2003. Camera trap, line transect census and track surveys: a comparative evaluation. Biological Conservation 114(3): 351–355. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(03)00063-6

Solari S., E. Vivar, P.M. Velazco & J.J. Rodriguez. 2001. Small mammals of the southern Vilcabamba region, Peru. In: L.E. Alonso, A. Alonso, T.S. Schulenberg y F. Dallmeier, eds. Biological and social assessments of the Cordillera de Vilcabamba, Peru. RAP Working Papers 12, and SIMAB Series 6, Conservation International, Washington, D.C. Pp. 110-116.

Solari S., V. Pacheco, L. Luna, et al. 2006. Mammals of the Manu Biosphere Reserve. In: B.D. Patterson, D.F. Stotz and S. Solari, Eds. Mammals and birds of the Manu Biosphere Reserve, Peru. Fieldiana Zoology 110: 13-22. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.2708

Tirira D. 2007. Mamíferos del Ecuador, Guía de Campo. Publicación Especial 6. Ediciones Murciélago Blanco. Quito.

Tobler M., S. Carrillo-Percastegui, R. Leite Pitman, R. Mares & G. Powell. 2008. An evaluation of camera traps for inventorying large- and medium-sized terrestrial rainforest mammals. Animal Conservation 11: 169–178. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1795.2008.00169.x

Tobler M. W., S. E. Carrillo-Percastegui, A. Zúñiga Hartley & G. V. Powell. 2013. High jaguar densities and large population sizes in the core habitat of the southwestern Amazon. Biological Conservation 159: 375–381. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2012.12.012

Wallace R., H. Gomez, G. Ayala & F. Espinoza. 2003. Camera trapping for jaguar (Panthera onca ) in the Tuichi valley , Bolivia. Mastozoología Neotropical 10: 133–139.

Wallace R. B., A. Reinaga, T. Siles, J. Baiker, I. Goldstein, et al. 2014. Andean Bear Priority Conservation Units in Bolivia & Peru. Wildlife Conservation Society, Centro de Biodiversidad Genetica de la Universidad Mayor de San Simón de Bolivia, Universidad Cayetano Heredia de Perú y Antwerp University. La Paz, Bolivia. 80 pp.

Wetzel R. M. 1975. The species of Tamandua Gray (Edentata, Myrmecophagidae). Proceedings of Biological Society of Washington 88 (:95–112.

Williams R. 2008. Mamíferos de Chaparrí. In: H. Plenge & R. Williams, eds. Guía de la vida silvestre de Chaparrí. Lima: Geográfica EIRL. Pp. 78-85.

Wunder S. 2001. Ecuador Goes Bananas: Incremental Technological Change and Forest Loss. In: Angelsen A. & D. Kaimowitz, eds. Agricultural Technologies and Tropical Deforestation. CAB International, Center for International Forestry Research. Pp. 167-194.

Zeller K. 2007. Jaguars in the New Millennium Data Set Update: The state of the Jaguar in 2006. Wildlife Conservation Society. 77pp.

Zeller K.A., S. Nijhawan, R. Salom-Pérez, S. H. Potosme & J. E. Hines. 2011. Integrating occupancy modeling and interview data for corridor identification: a case study for jaguars in Nicaragua. Biological Conservation 144: 892–901. doi: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2010.12.003

Funding:

Rufford Small Grants, 117811-1

Author contributions:

CMH designed the research, collected and analyzed the data, and drafted the article. VP contributed in the research design, helped analyze the data and critically reviewed the draft. Both authors approved the final draft.

There is no conflict of interest from any of the authors.

Autor para correspondencia

Email, Cindy Hurtado: cindymeliza@gmail.com

Email, Víctor Pacheco: vpachecot@unmsm.edu.pe

Presentado: 09/11/2014

Aceptado: 07/02/2015

Publicado online: 24/04/2015

Anexos