Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO  uBio

uBio

Compartir

Revista Peruana de Biología

versión On-line ISSN 1727-9933

Rev. peru biol. vol.23 no.2 Lima mayo/agos. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/rpb.v23i2.12423

10.15381/rpb.v23i2.12423

TRABAJOS ORIGINALES

Population density and primate conservation in the Noroeste Biosphere Reserve, Tumbes, Peru

Densidad poblacional y conservación de los primates de la Reserva de Biosfera del Noroeste, Tumbes, Perú

Cindy M. Hurtado 1,2, José Serrano-Villavicencio 1,3,* and Víctor Pacheco 1,4

1 Museo de Historia Natural, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Perú.

2 Centro de Investigación Biodiversidad Sostenible (BioS), Lima, Perú.

3 Mastozoología, Museu de Zoología - USP, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil.

4 Instituto de Ciencias Biológicas "Antonio Raimondi", Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Perú.

Abstract

The Noroeste Biosphere Reserve (NBR) is home to at least 22 species of medium and large mammals including the primates Alouatta palliata aequatorialis and Cebus albifrons aequatorialis. Previous estimates of A. p. aequatorialis population density vary from 2.3–8.6 ind/km2 in 1983 to 17–19 ind/km2 in 2005 and 2006, respectively. While for C. a. aequatorialis there are no estimates of population density in the NBR. In order to calculate the population density estimates for both species we installed six transects in 10.5 km2 within the Cerros de Amotape National Park (belonging to the NBR) from August 2012 to March 2013. Based on 112.3 km of transects we obtained a population density of 8.3 ± 3.6 ind/km2 for A. p. aequatorialis. However, for the reduced number of Cebus albifrons aequatorialis sightings we were only able to calculate a group size from three to 12 individuals and an encounter rate of 0.3 ind/km. Even though A. p. aequatorialis has potentially increased in population density, it is not feasible to make comparisons with previous estimates in the same area because of the different employed methodologies and the lack of randomness in the data collection. We recommend a long-term monitoring plan, including C. a. aequatorialis which makes it a conservation priority for the NBR, this monitoring plan should include mitigation of potential threats such as illegal hunting and trapping for the pet trade.

Keywords: Alouatta palliata aequatorialis; Cebus albifrons aequatorialis; distance sampling; line transect; Noroeste Biosphere Reserve.

Resumen

La Reserva de Biósfera del Noroeste (RBN) alberga por lo menos 22 especies de mamíferos medianos y grandes entre las cuales se encuentran los primates Alouatta palliata aequatorialis y Cebus albifrons aequatorialis. Los estimados previos de la densidad poblacional de A. p. aequatorialis varían de 2.3‒8.6 ind/km2 en 1983 a 17‒19 ind/km2 en 2005 y 2006, respectivamente. Mientras que para C. a. aequatorialis no existen estimados poblacionales para la RBN. Para calcular la densidad poblacional de estas dos especies instalamos seis transectos lineales en 10.5 km2 dentro del Parque Nacional Cerros de Amotape (perteneciente a la RBN) de agosto del 2012 a marzo del 2013. En base a 112.3 km de transectos se obtuvo una densidad poblacional de 8.3 ± 3.6 ind/km2 para A. p. aequatorialis; sin embargo, por el reducido número de avistamientos de Cebus albifrons aequatorialis solo se pudo calcular el tamaño de grupo que varió de tres a 12 individuos y la tasa de encuentro de 0.3 ind/km. A pesar que la población del A. p. aequatorialis aparentemente ha aumentado, no es factible hacer comparaciones con los estimados anteriores debido a las diferentes metodologías empleadas y a la falta de aleatoriedad en la toma de datos. Recomendamos un plan de monitoreo a largo plazo, que incluya a C. a. aequatorialis como objeto y prioridad de conservación para la RBN, el cual debería incluir la mitigación de posibles amenazas como caza y captura para comercio de mascotas.

Palabras clave: Alouatta palliata aequatorialis; Cebus albifrons aequatorialis; monitoreo; transecto lineal; Reserva de Biosfera del Noroeste

Introduction

The Noroeste Biosphere Reserve (NBR) was established by the UNESCO in 1977 (INRENA 2001) and includes three natural protected areas: El Angolo Hunting Reserve, Cerros de Amotape National Park (CANP) and Tumbes National Reserve. It protects the Equatorial dry forest (Brack-Egg 1986) and the Pacific Tropical Rainforest, the last found nowhere else in Peru (Chapman 1926, Brack-Egg 1986). The NBR holds fauna of Amazonian origin and biota similar to Central American forests (Lamas 1976, Cabrera & Willink 1980, Brack-Egg 1986, Cadenillas 2010). Unfortunately, the area adjacent to the Cerros de Amotape National Park and the Tumbes National Reserve: El Oro and Loja Provinces, in Ecuador, are highly fragmented for farming and agriculture (Dodson & Gentry 1991, Wunder 2001).

One of the NBR main objectives is the protection of the fauna and flora within its boundaries. In this area, the Primate Order is only represented by two confirmed species: Alouatta palliata aequatorialis Festa, 1903 (Ecuadorian mantled howler monkey) and Cebus albifrons aequatorialis Allen, 1914 (Ecuadorian capuchin monkey). However, Encarnación and Cook (1998), also registered, Saimiri sciureus, for the reserve but the current presence of a population is doubtful (Hurtado & Pacheco 2015).

The known distribution range for the Ecuadorian mantled howler monkey extends from Panama to Peru (Crockett 1998, Cuaron et al. 2008). Even though its southern known locality has been confirmed to be the Noroeste Biosphere Reserve; its northern limit range is not yet determined (Cortés-Ortiz et al. 2015). It is also categorized as Vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (Cuaron et al. 2008); and as Endangered by Peruvian legislation (Decreto Supremo N° 004-2014-MINAGRI).

The Ecuadorian capuchins monkey’s distribution range is restricted to western Ecuador and northwestern Peru (Jack & Campos 2012); unfortunately by 1988 the western forest of Ecuador had lost 95% of its original cover (Dodson & Gentry 1991). With such a restricted distribution, Campos and Jack (2013) made a potential distribution assessment, identifying three priority areas for Ecuadorian capuchins conservation, one of them, the Noroeste Biosphere Reserve. Moreover, Cebus

a. aequatorialis is now considered critically endangered by the IUCN (Cornejo & de la Torre 2015) while Peruvian legislation does not list it at-any risk category.

The aims of this work were to i) provide new density estimates for the Ecuadorian mantled howler monkey in the NBR, and ii) provide the first information on group sizes and relative abundance of the Ecuadorian capuchin monkeys in the NBR. This assessment is basic for a better conservation plan for these highly endangered species and to encourage further research questions.

Material and methods

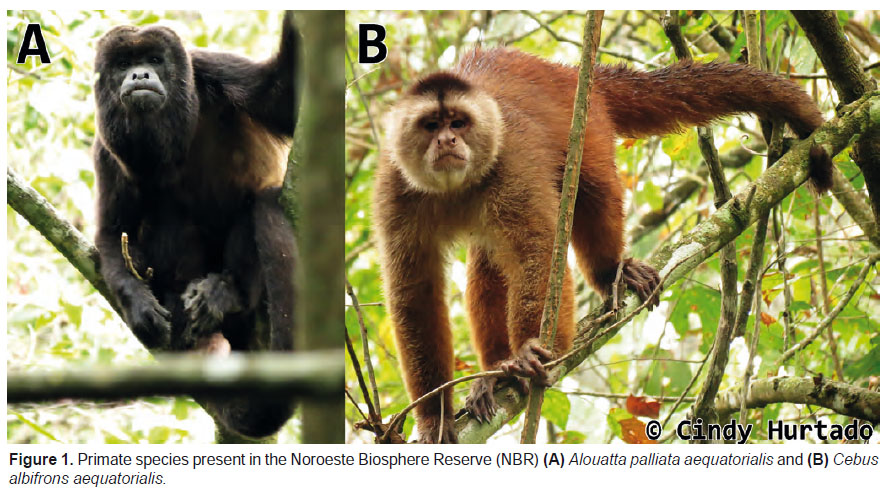

Study species.- Mantled howler monkeys (Fig. 1A) are facultative folivorous species (Milton 1982) and even though their vocalizations can be heard up to 1 km depending on the vegetation, they are cryptic animals hard to register (Dechner 2011). To the best of our knowledge, there is not a complete taxonomic revision nor diagnosis of the Alouatta palliata populations distributed in Central and South America, but A. p. aequatorialis is restricted to this area and its distribution is imprecise (Cortés-Ortiz et al. 2015). For this reason, Cortés-Ortiz et al. (2015) suggested studies with a larger number of samples to determine the current taxonomic status of the populations distributed in the NBR and Southern Ecuador.

The taxonomic status of the Ecuadorian white-fronted capuchin, Cebus albifrons, is now debatable. In the only comprehensive taxonomic revision of the genus Cebus (currently divided into the genera Sapajus and Cebus), Hershkovitz (1949) considered that the Cebus aequatorialis of Allen (1914) actually represents a subspecies of Cebus albifrons, considered as C. a. aequatorialis.

Cornejo and de la Torre (2015), based on Lynch Alfaro et al. (2010) and Boubli et al. (2012), considered C. a. aequatorialis as originally proposed by Allen (1914), Cebus aequatorialis. However, upon a detailed review of the literature, several concerns for the validity of this species arose. Lynch Alfaro et al.’s (2010) publication lacks detailed information such as origin, number of specimens used, and detailed methods. In addition, Boubli et al. (2012), performed a molecular phylogenetic analysis of 50 samples of untufted capuchins (genus Cebus), where they could not obtain samples of C. a. aequatorialis (see Boubli et al. 2012; p. 383). We do not deny that the populations of C. a. aequatorialis in the NBR may represent an isolated taxon; nevertheless, we considered that there is still not enough evidence to elevate it to the full species rank. Therefore, in this paper, we will treat the populations of the Ecuadorian white-fronted capuchin as proposed by Hershkovitz (1949), Cebus albifrons aequatorialis (Fig 1B).

In reference to the only report of Saimiri sp. (considered as Saimiri cf. sciureus) observed by Encarnación and Cook (1998); there is evidence of only one additional sighting of one individual in 2008 near the NBR (3.79°S, 80.26°W) (Renzo Piana comm. pers.). This sighting could be a result of trafficking in wildlife, or a remnant of the groups mentioned by Encarnación and Cook (1998) since the distribution of the genus Saimiri does not extend to the western side of the Andes (Hershkovitz 1949). For these reasons, Hurtado and Pacheco (2015) considered that if the species was truly present in the NBR, it is probably already locally extinct.

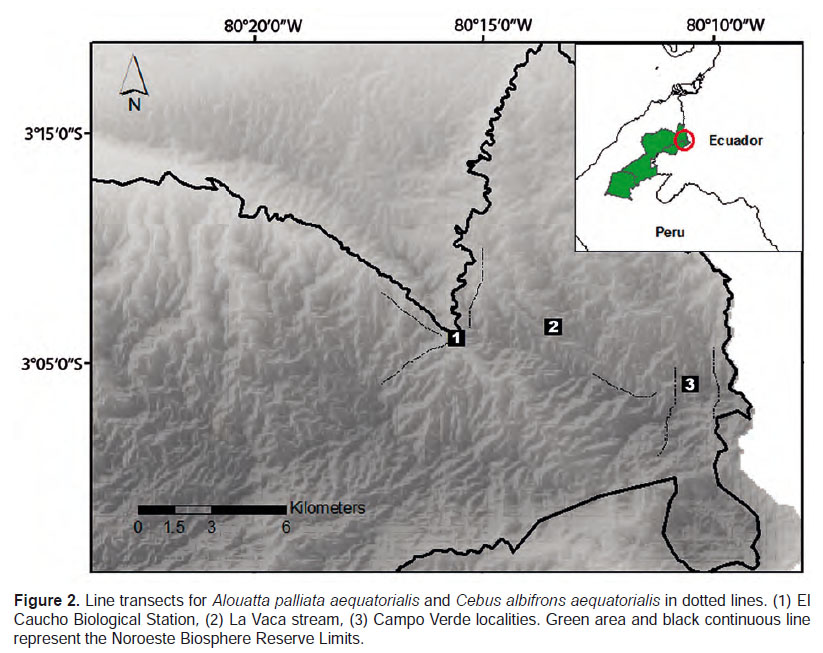

Study area.- The CANP is located in the northeastern region of the NBR in the Tumbes Province, Peru (03°50’S, 80°16’ W). Three major forest types can be distinguished in the Park: Equatorial Dry Forest (EDF), Pacific Tropical Rainforest (PTR), and a Transitional Forest (TF) (Brack-Egg 1986). We selected one locality in the TF (El Caucho Biological Station) and one in the PTR (Campo Verde) because no previous sightings or reports were obtained in the EDF. The Pacific Tropical Rainforest is characterized by marked seasonality, the rainy season (January – March) and dry season (April-December) where precipitation is up to 1537 mm/year and temperature fluctuates from 19 to 35 °C (INRENA 2001).

El Caucho Biological Station (03°50’S, 80°16’W, 355 m.), represents the Transition Forest, characterized by Ceiba trischistandra, Cavanillesia platanifolia, Ficus jacobii, Triplaris cumingiana, Bougainvillea peruviana, Tessaria integrifolia, Inga feuillei, and Cecropia peltata (Ponte 1998, Pacheco et al. 2007).

Campo Verde (03°50’S, 80°10’W, 750 m), is characterized by a dense perennial forest, hilly terrain and high humidity (Ponte 1998). The characteristic species of this area are Centrolobium ochroxylum, Cordia eriostigma, Tabebuia chrysantha, Triplaris cumingiana, Gallesia integrifolia, Ficus jacobii, and Cedrela fissilis (Ponte 1998, Pacheco et al. 2007).

Data collection.- We surveyed six transects in 10.5 km2, each transect of 4 km and three per locality. We were not able to randomly select transects because of logistics and park protection constraints. However, we tried stratification by selecting existing trails that cross several vegetation types and considered straightening of the trails and distance between them (Buckland et al. 2001). Furthermore, transects along streams or flooded areas were avoided to account for overestimation when the abundance of high-quality resources yield higher detection probability or encounter rate (Peres 1997, Bravo & Sallenave 2003). Instead we selected trails that only crossed streams.

Between August 2012 and February 2013, following Peres and Cunha’s (2011) methodology, two people walked each of the six transect at approximately 1.2 km/hour, starting between 6:00 and 7:30 am (Fig. 2). We did not census the return transect. We only census primates during the day, accumulating 37 sampling days. The data collected per census were: the transect number, date, time, and the total distance walked. For each sighting, we recorded time, species, the number of individuals, perpendicular distance to the first individual detected, coordinates, and behavior (Marshall et al., 2008); to calculate perpendicular distance we used a rangefinder (Bushnell Yardage Pro, 5 – 100 yards).

Data analyses.- Data Analyses consisted in calculating density estimates for species with more than 12 sightings (A. p. aequatorialis) and encounter rates for species with fewer records (C. a. aequatorialis), we only used data collected during the transect census and did not include occasional sightings to avoid overestimation. To calculate population density we used the Distance sampling method with Distance 6.0 software (Thomas et al. 2010). For the selection of the best model we used the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and a coefficient of variation lower than 30% (Buckland et al. 2001). Distance sampling is commonly employed in tropical forests (Peres 1999, Jathanna et al. 2003, Araldi et al. 2014) and should provide a baseline for future monitoring plans with comparable data in the NBR.

For species with a lower quantity of records (<12) we calculated encounter rates as the number of individuals observed per distance walked (Marshall et al. 2008).

Results and discussion

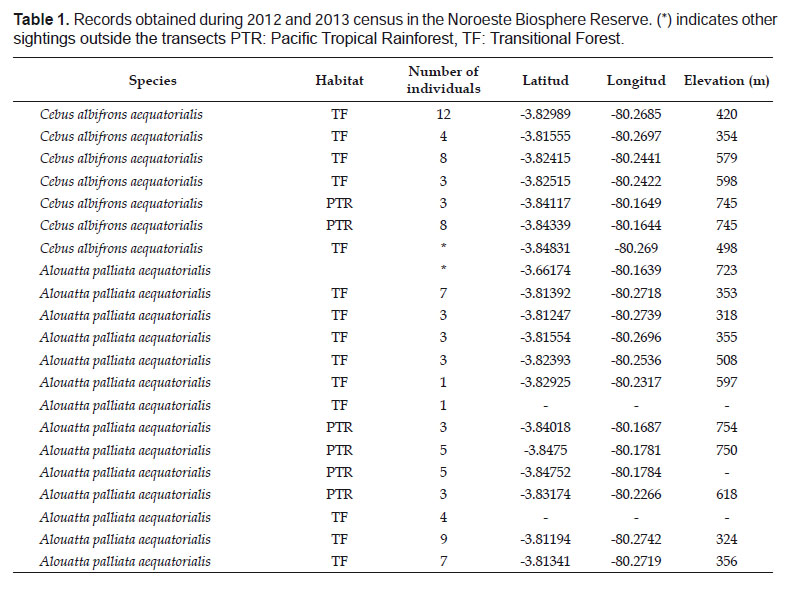

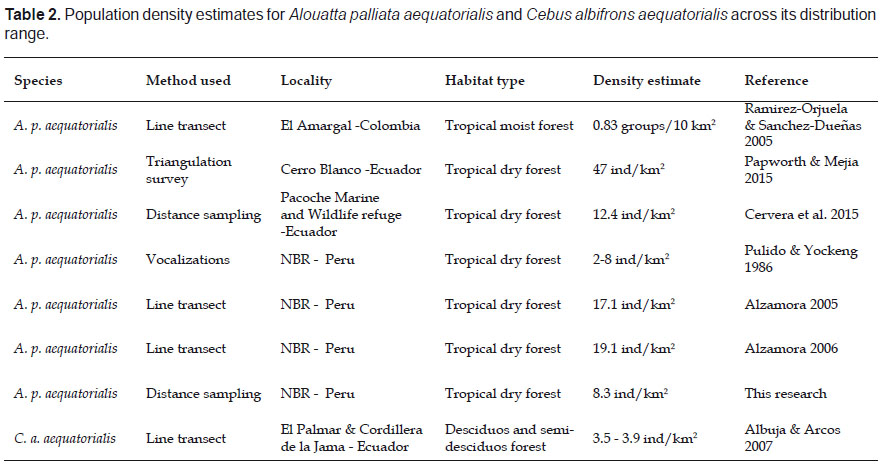

We obtained 19 primate independent observations of two species of primates, Cebus albifrons aequatorialis and Alouatta palliata aequatorialis in 112.3 km of sampling effort. For A. p. aequatorialis we registered 13 independent observations (Table 1) with group sizes from one (male) to nine individuals (x= 4.15). Moreover, we calculated a population density of 8.3 ± 3.6 ind/ km2 (AIC= 96.5) (Table 2).

For C. a. aequatorialis we obtained six independent observations (Table 1). Group sizes ranged from 3 to 12 individuals (x= 6.3) and the encounter rate was 0.3 ind/km.

Alouatta palliata aequatorialis

The scenario for the population in Tumbes has potentially improved since the 1980’s. One of the first primate assessments and population density estimates in the NBR for A. p. aequatorialis were based on a few sightings (Pulido & Yockteng 1986, Encarnación & Cook 1998).

In 1986, Pulido and Yockteng’s expedition had difficulty registering howler monkeys, which could be attributed to the lack of protection, hunting pressure in the area, and the shy behavior of the individuals. However, after 41.1 km in 2.58 km2 they registered five vocalizations and no direct observation; and calculated a population density of 4.19 ind/km2. Furthermore, after two sightings in the Cabo Inga sector, they adjusted their density estimate to 2.3 to 8.6 ind/km2 (Table 2).

These low population estimates had potentially increased when Encarnación and Cook (1998) found two troops of A. p. aequatorialis consisting of 20 and ten individuals, plus one solitary monkey which was associated to the riparian forest, in the surrounding area of la Vaca and el Ciruelo streams. Moreover, between November 2003 and June 2004, Alzamora (2005) surveyed two streams within the NBR and calculated a population density of 17.1 ind/km2. In 2006, the same author counted 142 mantled howler monkeys near el Caucho Biological Station and Campo Verde (localities surveyed in this research) and obtained a population density of 19.1 ind/km2 (Table 2).

Our estimate of 8.3 ± 3.6 ind/km2 for almost the same localities surveys do not represent a decline in howlers populations, but a difference in the methodology employed. Previous estimates made by Alzamora (2005, 2006) could represent an overestimation due to sampling near streams which according to Encarnacion and Cook (1998) is the preferred habitat of this species within the NBR. This tendency towards riverine areas was also noted by Stoner (1996), who determined the selection of black howlers in Costa Rica was linked to rivers and streams as well as primary forest.

Even though our density estimate was non-randomized and to some degree could represent an underestimation of the howler’s population size, we covered streams (preferred habitats) as well as transects in the middle of the forest (less preferred habitats). These distinct methodologies and survey design make these studies harder to compare and could explain the different results. However, our results confirm that populations of A. p. aequatorialis are recovering.

Mantled Howler monkey’s population density varied across its distribution range, representing low estimates in Colombia, 0.83 groups/10 km2 (Ramirez-Orjuela & Sanchez-Dueñas 2005) and contrasting estimates in Tropical Dry Forest of Ecuador, from 47 ind/km2 (Papworth & Mejia 2015) to 12.4 ind/km2 (Cervera et al. 2015). Again, these estimate differences can be attributed to the different methods used such as Triangulation surveys (Papworth and Mejia 2015), playback calls (Salcedo et al. 2014), line transects and survey duration (Ramirez-Orjuela & Sanchez-Dueñas 2015, Cervera et al. 2015), which makes difficult comparisons among areas and time. We recommend using line transects and distance sampling across this primate distribution to assess population changes and dynamics.

Cebus albifrons aequatorialis

Previous information for the NBR reported group sizes of three to five individuals in two different years 1980 and 1994 (Cook & Encarnacion 1998); however no population density was estimated. Additionally, in western Ecuador, after surveying 28 localities and only confirming the presence of C. a. aequatorialis in eight, density was calculated as 3.5 and 3.9 ind/km2 (Albuja & Arcos 2007). In the Pacoche Marine and Wildlife Refuge, in the coast of Ecuador, Cervera et al. (2015) recorded only three observations of C. a. aequatorialis outside 90 km of transects census, indicating a low population size and immediate need for conservation in Ecuadorian populations. With the low encounter rate we obtained added to the low-density estimates obtained through their distribution, this subspecies should be considered for priority conservation within the NBR.

Because of the several different data analyzes and methodologies (different localities and seasons), it is hard to quantify population trends and dynamics of both primates within the NRB. However, primate populations can vary depending on several factors: population growth rates, hunting pressure, diseases, increase in predation rate, and the decrease in habitat suitability, among others (Chapman & Balcomb 1998, Carrera-Sánchez et al. 2003). Moreover, ENSO events affect the NBR every few years, altering rainfall patterns and plant productivity (Holmgren et al. 2006, Holmgren et al. 2001), and these changes should be considered in future assessments.

In order to elucidate current population trends of Alouatta palliata aequatorialis and Cebus albifrons aequatorialis in the NBR, it is imperative to implement a long-term monitoring plan, with detailed and uniform methodology. An assessment of the primate capture for pet trade is also needed. In the adjacent forest in Ecuador, C. albifrons represents 27% of illegal mammal captures and 50% of primate captures which makes this species a common target (de la Torre 2012). Considering the NBR is located in the limit of Ecuador and previous hunting attempts from Ecuadorians in the area of Campo Verde, an increased and continuous monitoring of this area is necessary to reduce the effects of illegal hunting. Furthermore, the lack of information about this species in Peru added to the low population density and connectivity of the remnant suitable areas in Ecuador (Albuja & Arcos 2007, Campos & Jack 2013, Cervera et al. 2015) should give this species the higher legal protection by the Ministerio del Ambiente in Peru.

Acknowledgments

This research was financed by the Rufford Small Grants foundation. We would like to thank the park guards and managers of the Cerros de Amotape National Park, especially to Alan Garcia Cruz, Liliana Reaño, Arturo Noblecilla, Ilme Aleman, and Luis Grippa. We also thank the volunteers: Jaime Pacheco, Cynthia Musaja and Jesus Muñoz for the incredible support during fieldwork. Also, we would like to thank Dr. Renzo Piana for information provided for this manuscript.

Literature cited

Albuja L. & R. Arcos. 2007. Evaluación de las poblaciones de Cebus albifrons cf. aequatorialis en los bosques suroccidentalesecuatorianos. Revista Politécnica Biología 7: 59–69.

Allen J.A. 1914. New South American Monkeys. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 33:647-655. [ Links ]

Alzamora M. 2005. Población y Hábitos alimenticios de Alouatta palliata aequatorialis (Gray, 1849) "Mono Coto de Tumbes", enla Zona Reservada de Tumbes. Sector Las Pavas – La Unión. Tesis para optar el grado de Biólogo por la UniversidadNacional de Piura. [ Links ]

Alzamora M. 2006. Población y uso de hábitat por Alouatta palliata aequatorialis "Mono coto de Tumbes" en la Zona Reservada de Tumbes, Sector El Caucho y Campo verde. ReporteTécnico Naturaleza y Cultura Internacional – Conservation International. [ Links ]

Araldi A., C. Barelli, K. Hodges, & F. Rovero. 2014. Density estimation of the endangered Udzungwa red colobus (Procolobus gordonorum) and other arboreal primates in the Udzungwa Mountains using systematic distance sampling. International Journal of Primatology 35(5): 941-956. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10764-014-9772-6 [ Links ]

Boubli J.P., A.B. Rylands, I. Farias, M. Alfaro & J. Lynch Alfaro. 2012.Cebus phylogenetic relationships: a preliminary reassessmentof the diversity of the untufted capuchin monkeys. AmericanJournal of Primatology 74(4): 381-393. 10.1002/ajp.21998 [ Links ]

Brack-Egg A. 1986. Las ecorregiones del Perú. Boletín de Lima 44:57-70. [ Links ]

Bravo S. P., & A. Sallenave. 2003. Foraging behavior and activitypatterns of Alouatta caraya in the northeastern Argentinean flooded forest. International Journal of Primatology 24(4): 825-846. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1024680806342 [ Links ]

Buckland S.T, D.R. Anderson, K.P. Burnham, J.L Laake, D.L Borchers & L. Thomas. 2001. Introduction to Distance Sampling, Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Cabrera A. & A. Willink. 1980. Biogeografía de América Latina, 2nd edition. Serie Biología, Secretaria General de la Organizaciónde los Estados Americanos, Washington D.C. 122pp. [ Links ]

Cadenillas R. 2010. Diversidad, ecología y análisis biogeográfico de los murciélagos del Parque Nacional Cerros de Amotape, Tumbes-Perú. Tesis para optar el grado académico de Magister en Zoología por la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. Lima-Perú [ Links ].

Campos F. A. & K.M. Jack. 2013. A potential distribution model and conservation plan for the critically endangered Ecuadorian capuchin, Cebus albifrons aequatorialis. International Journal of Primatology 34(5): 899-916. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10764-013-9704-x [ Links ]

Carrera-Sánchez E., G. Medel-Palacios & E. Rodríguez-Luna. 2003. Estudio poblacional de monos aulladores (Alouatta palliata mexicana) en la Isla Agaltepec, Veracruz, México. Neotropical Primates 11 (3): 176-180. [ Links ]

Cervera L., D.J. Lizcano, D.G. Tirira & G. Donati. 2015. Surveying Two Endangered Primate Species (Alouatta palliata aequatorialis and Cebus aequatorialis) in the Pacoche Marineand Coastal Wildlife Refuge, West Ecuador. International Journal of Primatology 36(5): 933-947. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10764-015-9864-y [ Links ]

Chapman F.M. 1926. The Distribution of Bird-Life in Ecuador A Contribution to a Study of the Origin of Andean Bird-life. Bulletin of The American Museum of Natural History. V 55. Pp. 786. Chapman C.A. & S.R. Balcomb. 1998. Population characteristics of howlers: ecological conditions or group history. International Journal of Primatology 19(3):385-403. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1020352220487 [ Links ]

Cornejo F. & S. de la Torre. 2015. Cebus aequatorialis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T4081A81232052. Downloaded on 02 February 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015.RLTS.T4081A81232052.en [ Links ]

Cortés-Ortiz L., A.B. Rylands, & R.A. Mittermeier. 2015. The taxonomy of howler monkeys: Integrating old and newknowledge from morphological and genetic studies, in: M.M. Kowalewski, P.A. Garber, L. Cortés-Ortiz, B. Urbani and D. Youlatos, eds. Howler Monkeys: Adaptive Radiation, Systematics, and Morphology. Springer New York,New York. Pp. 55–84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-14939-1957-4_3. [ Links ]

Crocket C. M. 1998. Conservation biology of the genus Alouatta. International Journal of Primatology 19(3): 549-578. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1020316607284 [ Links ]

Cuarón A.D., Shedden, A., Rodríguez-Luna, E., de Grammont, P.C. &Link, A. 2008. Alouatta palliata ssp. aequatorialis. The IUCNRed List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T919A13095200. Downloaded on 30 July 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T919A13095200.en. [ Links ]

Dechner A. 2011. Searching for Alouatta palliata in Northern Colombia: Considerations for the Species Detection, Monitoring and Conservation in the Dry Forests of Bolívar, Colombia. Neotropical Primates 18(1): 1-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1896/044.018.0101 [ Links ]

D.S. N° 004-2014-MINAGRI. 2014. Decreto Supremo que aprueba la actualización de la lista de clasificación y categorizaciónde las especies amenazadas de fauna silvestre legalmenteprotegidas. El Peruano, Normas Legales, Martes 8 de abril de 2014: 520497-520504. [ Links ]

de la Torre, S. 2012. Conservation of Neotropical primates: Ecuador – acase study. International Zoo Yearbook, 46: 25–35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-1090.2011.00158.x [ Links ]

Dodson C.H. & A.H. Gentry. 1991. Biological extinction in Western Ecuador. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 78(2):273-295. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2399563 [ Links ]

Encarnación, F. & G. Cook. 1998. Primates of the Tropical Forest of the Pacific Coast of Peru: The Tumbes Reserved Zone. Primate Conservation 18:15-20. [ Links ]

Hershkovitz P. 1949. Mammals of northern Colombia. Preliminary report No. 4: Monkeys (Primates) with taxonomic revisions of some forms. Proceedings of the United States National Museum 98: 323–427. [ Links ]

Holmgren M., M. Scheffer, E. Ezcurra, J.R. Gutiérrez & G.M. Mohren. 2001. El Niño effects on the dynamics of terrestrial ecosystems. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 16(2): 89-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(00)02052-8 [ Links ]

Holmgren M., P. Stapp, C.R. Dickman, C. Gracia, S. Graham, J.R. Gutiérrez, et al. 2006. Extreme climatic events shape arid and semiarid ecosystems. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 4(2): 87-95. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1890/1540-9295(2006)004[0087:ECESAA]2.0.CO;2 [ Links ]

Hurtado C. & V. Pacheco. 2015. Nuevos registros de mamíferos en el Parque Nacional Cerros de Amotape, noroeste de Perú. Revista Peruana de Biología 22(1): 77-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/rpb.v22i1.11124 [ Links ]

INRENA 2001. Estrategia de conservación y desarrollo sostenible de la Reserva de Biosfera del Noroeste 2001-2010. Instituto Nacional de Recursos Naturales. Tumbes-Perú. 93pp. [ Links ]

Jack K. M. & F.A. Campos. 2012. Distribution, abundance, and spatialecology of the critically endangered Ecuadorian capuchin (Cebus albifrons aequatorialis). Tropical Conservation Science 5(2): 173-191. [ Links ]

Jack K. M. & F.A. Campos. 2012. Distribution, abundance, and spatialecology of the critically endangered Ecuadorian capuchin (Cebus albifrons aequatorialis). Tropical Conservation Science Vol. 5(2):173-191. [ Links ]

Jathanna D., K.U. Karanth & A.J.T. Johnsingh. 2003. Estimation of large herbivore densities in the tropical forestsof southern India using distance sampling. Journal ofZoology 261(3): 285-290. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0952836903004278 [ Links ]

Lamas G. 1976. Notas sobre mariposas peruanas (Lepidoptera). III. Sobre una colección efectuada en el departamento de Tumbes. Revista peruana de entomología 19(1): 8-12. [ Links ]

Lynch Alfaro J., D. Schwochow, F. Santini & M.E. Alfaro. 2010.Capuchin phylogenetics and statistical phylogeography:implications for behavioral evolution. In: Abstracts andProgram: International Primatological Society XXIII Congress Kyoto, 12–18 September 2010. Primate Research26(suppl.): 253 (Abstract). [ Links ]

Marshall A. R., J.C. Lovett & P.C. White. 2008. Selection of linetransect methods for estimating the density of group-living animals: lessons from the primates. American Journal ofPrimatology 70(5): 452-462. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20516 [ Links ]

Milton K. 1982. Dietary quality and demographic regulation in a howler monkey population, in: E. Leigh, S.A. Rands and

D. Windsor, eds. The ecology of a tropical forest: Seasonal rhythms and long-term changes. Washington, DC,273–289.

Pacheco V., R. Cadenillas, S. Velazco, E. Salas & U. Fajardo. 2007. Noteworthy bat records from the Pacific Tropical rainforest region and adjacent dry forest in northwestern Peru. Acta Chiropterologica 9(2): 409–422. http://dx.doi.org/10.3161/1733-5329(2007)9[409:NBRFTP]2.0.CO;2 [ Links ]

Papworth S. & M. Mejia. 2015. Population density of Ecuadorian mantled howler monkeys (Alouatta palliata aequatorialis) in a tropical dry forest, with information on habitat selection, calling behavior and cluster sizes. Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment, 50(2): 65-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01650521.2015.1033939 [ Links ]

Peres C. A. 1997. Primate community structure at twenty western Amazonian flooded and unflooded forests. Journal of Tropical Ecology 13(3): 381-405. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0266467400010580 [ Links ]

Peres C. A. 1999. General guidelines for standardizing line-transect surveys of tropical forest primates. Neotropical primates7(1): 11-16. [ Links ]

Peres C. A. & A. A. Cunha. 2011. Manual para censo e monitoramentode vertebrados de medio é grande porte por transecçao linearem florestas tropicais. 26pp. [ Links ]

Ponte M. 1998. Inventario y análisis florístico de la estructura del bosque, in W. Wust, ed. La Zona Reservada de Tumbes-biodiversidad y diagnóstico socioeconómico. The John D. and Catherine C. MacArthur Foundation/Fondo Nacional por Las Áreas Protegidas por el estado (PROFONANPE), Lima. Pp. 43-65. [ Links ]

Pulido V. & C. Yockteng. 1986. Conservación de la fauna silvestre en el Bosque Nacional de Tumbes, con especial referencia al «coto mono», in: P. Aguilar, ed. Simposio Conservación y Manejo de la Fauna Silvestre Neotropical. IX CLAZ Perú. Lima. Pp. 33-43. [ Links ]

Ramírez-Orjuela, C. & I.M. Sánchez-Dueñas. 2005. Primer censodel mono aullador negro (Alouatta palliata aequatorialis)en El chocó biogeográfico Colombiano. NeotropicalPrimates 13(2): 1-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1896/14134705.13.2.1 [ Links ]

Salcedo, A. R., M. Mejia, K. Slocombe & S. Papworth, S. 2014.Two Case Studies Using Playbacks to Census NeotropicalPrimates: Callicebus discolor and Alouatta palliata aequatorialis. Neotropical Primates 21(2): 200-204. http://dx.doi.org/10.1896/044.021.0209 [ Links ]

Stoner K. 1996. Habitat Selection and Seasonal Patterns of Activityand Foraging of Mantled Howler Monkeys (Alouatta palliata) in Northeastern Costa Rica. International Journal of Primatology 17: 1-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02696156 [ Links ]

Thomas, L., S.T. Buckland, E.A. Rexstad, J. L. Laake, S. Strindberg, S.

L. Hedley, J. R.B. Bishop, T. A. Marques & K. P. Burnham. 2010. Distance software: design and analysis of distance sampling surveys for estimating population size. Journal of Applied Ecology 47: 5-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2009.01737.x

Wunder S. 2001. Ecuador Goes Bananas: Incremental Technological Change and Forest Loss, in: Angelsen A. & D. Kaimowitz, eds. Agricultural Technologies and Tropical Deforestation. CAB International, Center for International ForestryResearch. [ Links ]

Fuentes de financiamiento: Rufford Small Grants 117811-1

*Autor para correspondencia:

José Serrano-Villavicencio Museu de Zoología, Mastozoología Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo Av. Nazaré 481, Ipiranga, CEP 481 04263-000 (Brasil) Teléfono: +55 11 2065-8100 - Fax: +55 11 2065-8115

Email Cindy Hurtado: c.hurtado@biosperu.org

Email José E. Serrano-Villavicencio: serranovillavicencio@gmail.com

Email, Víctor Pacheco: vpachecot@unmsm.edu.pe

Información sobre los autores:

CH realizó la toma de datos en campo, análisis y la redacción del artículo. JS- participó en el diseño, redacción y correcciones del artículo. VP participó en el diseño de muestro, revisión de los análisis y correcciones en la redacción del artículo.

Los autores no incurren en conflictos de intereses.

Permisos de colecta:

Servisio Nacional Forestal y de Fauna Silvestre (SERFOR) del Ministerio de Agricultura y Riego - permisos de recolección No. 084-2012-AGDGFFS-DGEFFS - 0148-2013-AG-DGFFS-DGEFFS

Presentado: 21/03/2016

Aceptado: 13/07/2016

Publicado online: 27/08/2016