Introduction

Floristic and phytosociological studies are extremely useful for improving the knowledge about species distributions, giving support to biogeographic inferences, and contributing to both species and ecosystems conservation (Cardoso & Queiroz 2007, Moro et al. 2016). For Caatinga, one of the largest and most threatened centres of dry tropical forest in the world, analyses of similarity and scrutiny of the floristic composition have been used to circumscribe its heterogeneous vegetation types (Linares-Palomino et al. 2010, Moro et al. 2014, Moro et al. 2016, Queiroz 2017).

Many phytophysiognomies are found inside the geographic limits of the Caatinga biome in Eastern Brazil, including semi-deciduous forests, montane cloud forests, rupicolous vegetation growing on quartzitic soils (campo rupestre) and even enclaves of Brazilian savanna. In the present work, the vegetation focussed on is Caatinga sensu stricto. This is characterised by woody deciduous vegetation of variable density and height, a seasonal and discontinuous herbaceous stratum, and the presence of prickly or spiny and/or succulent plant species. The species are adapted to the semiarid climate, with marked seasonality and scarce and irregularly distributed rains (Andrade-Lima 1981, Pennington et al. 2000, Silva et al. 2004). Due to these extreme conditions and its geographical isolation from other SDTF groups (Linares-Palomino 2010) by the barriers formed by the seasonal, fire exposed Cerrado and perhumid Amazon Rainforest biomes, the Caatinga presents almost 530 species of endemic flora (Fernandes et al. 2020).

Despite of Caatinga been considered as a relatively homogeneous vegetation unit in biogeographical and/or ecological large-scale inferences by some authors (Pennington et al. 2000, Linares-Palomino et al. 2010 ). Andrade-Lima (1981) recognized at least 12 different types of vegetation within this biome, however, several works have subsequently pointed out relationships between substrates and different types of vegetation (Queiroz 2006, Moro et al. 2016), such as diversity heterogeneity at local scales (Costa et al. 2015), for example, as in the distribution of Leguminosae (Cardoso & Queiroz 2007) and Cactaceae (Taylor & Zappi 2004). This diversity of vegetation types is defined, primarily, by the association with large geomorphological units, for example, the Chapada Diamantina and Chapada do Araripe (Velloso 2002) and, secondarily, with the water availability, including the different rainfall periods throughout the year (Rocha et al. 2004, Queiroz 2006, Costa et al. 2015).

Studies of the diversity, distribution, and endemism of Leguminosae in physiognomically similar areas of Caatinga have shown that this biome is subdivided into historically distinct biotas (Queiroz 2006, Cardoso & Queiroz 2007). Within these, the phytophysiognomies of the sandy sedimentary surfaces present higher density of individuals per species than the areas associated with a crystalline base (Andrade-Lima 1981, Rocha et al. 2004, Queiroz 2006, Cardoso & Queiroz 2007). A different floristic composition between these two substrates has also

been found in several studies (Rocha et al. 2004, Gomes et al. 2006, Queiroz 2006, Cardoso & Queiroz 2007, Santos et al. 2012, Costa et al. 2015, Moro et al. 2015, Moro et al. 2016). Another type of Caatinga, found on limestone outcrops of the bambuí group, to the west of Bahia and Minas Gerais, has been highlighted by Taylor and Zappi (2004), however, there are very few floristic lists dealing with this vegetation.

In general, the environmental characteristics of dry forests reflect a high abundance and relative diversity of succulent plants adapted to arid climate such as Cactaceae (Pennington et al. 2000, Taylor & Zappi 2004, Moro et al. 2016, Climate-date.org 2018). As eastern Brazil is the third centre of diversity for the Cactaceae family, with 154 species (Taylor & Zappi 2018), a fine scale analysis of cactus diversity, taking into account the different physiognomies of the Caatinga (Moro et al. 2014, Zappi et al. 2011, Queiroz et al. 2017) is much needed.

Therefore; it is clear, that Caatinga biodiversity comprises different distribution patterns, and with the help of vegetation structure analysis from floristic studies, we could answer the following questions: Is there a difference in the distribution of Cactaceae in different types of geomorphological formations? Does floristic composition and the density of individuals/ species vary according to the different physiognomies of Caatinga? Is there evidence that well preserved areas within the Caatinga show richness and density of individuals/species in relation to the other areas analysed?

Material and methods

A revision of floristic and phytosociological studies (woody component using the inclusion criteria of plants generally superior to 5 cm in diameter at ground height and 1m height) published for areas of the Caatinga biome, with specific focus on Caatinga sensu stricto, based on bibliographical searches available at Scielo and Periódicos Capes sites was performed (Table 1). Key words were: phytosociology, floristics, structure survey, and floristic survey plus Caatinga. Some studies were taken from Moro et al. (2014), who did an extensive revision up to 2011. The selection criteria of the studies were the presence of Cactaceae species in the sample, and the existence of a deposited voucher that allowed us to check their identification. For the phytosociological studies we chose only the ones that presented the density parameter (absolute or relative).

Information about geomorphological formations, ecoregions and coordinates were used to classify the Caatinga into four different types of physiognomies (Moro et al. 2016), as follows: 1) sedimentary, where the soil is deeper and with a larger water retention and the vegetation is generally less deciduous, with almost 50% of woody species maintaining their foliage even in the driest periods; 2) crystalline, where the soils are shallower and almost 26% of woody vegetation lose their leaves in the dry period (Rocha et al. 2004); 3) transition between sedimentary and crystalline soils; 4) tree Caatinga, a vegetation transitioning between the Caatinga and Cerrado, but floristically more related to the first (Santos et al. 2011); 5) riverside Caatinga, a vegetation along river courses, characterised by generally evergreen vegetation (Moro et al. 2016) (Figure 1).

For the categorization of conservation status, the areas were classified in three categories: 1) human disturbed areas: areas under human interference, through cutting vegetation or by utilising the soil for agriculture or livestock and mining of rocks; 2) desertification nucleus: areas that are going/have been through the process of losing their plant coverage; 3) preserved areas: areas with more than 20 years without registered use, and the areas within conservation units. All this information was extracted from selected articles (Table 1).

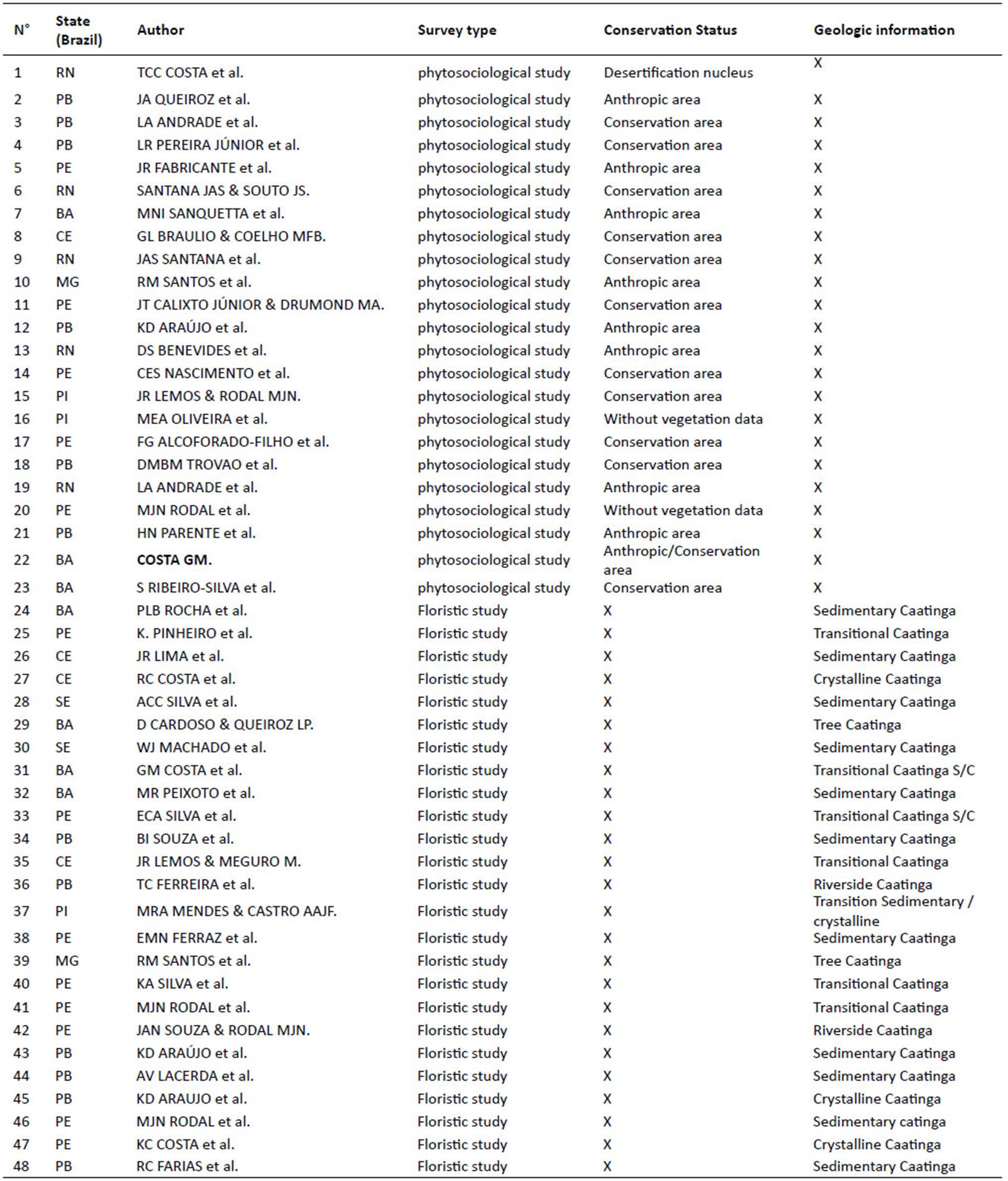

Table 1 List of publications on Caatinga sites that include cacti, consulted for floristic and phytosociologic data. Brazilian state acronyms: BA: Bahia, CE: Ceará, MG: Minas Gerais, PB: Paraíba, PE: Pernambuco, PI: Piauí, RN: Rio Grande do Norte, SE: Sergipe.

Figure 1 Phytophysiognomies of Caatinga in Bahia State. ARiverside Caatinga at "Contendas do Sincorá" Forest Area (Photo by L. Marinho); BCrystalline Caatinga at "Contendas do Sincorá" Forest Area; CRocky outcrop associated with Caatinga at Boa Nova National Park; Sedimentary Caatinga at Tucano, Bahia (Photo by D. Cardoso); ETree Caatinga at Ribeira do Pombal, Bahia (Photo by J.M. Nascimento Júnior); FHuman interference Caatinga at Cabaceiras do Paraguaçu.

For floristic analyses, a similarity matrix was prepared by combining the species list from different areas with the species names updated according to BFG (2018). The analyses were performed in the PAST software (Hammer et al. 2001). The phytosociological parameters of relative density and number of individuals were transformed in absolute density to enable comparisons (Table 2) by dividing the number of individuals per species per sampled area using data available in the selected papers. After the standardisation was completed, PAST software was also used to carry out an NMDS analysis (Non-metric multidimensional scaling), utilising the Bray-Curtis index, with a base in the species density of Cactaceae species. In order to group cacti species and Caatinga phytophysiognomies, a Cluster analysis with similarity determined through a Sorensen index was performed. A dendrogram was obtained from the presence and absence species matrix, including only species that occurred in more than one area (Hammer et al. 2001).

Results

A total of 48 studies were selected, two of which were floristic and 24 phytosociological (Table 1).

Presence of cactus species in floristic surveys of Caatinga biome

Thirty-three species were compiled for the Caatinga vegetation (Table 2), belonging to 14 genera. Cereus jamacaru DC. was the most frequent species in the surveys, appearing in 17 studies, followed by Pilosocereus gounellei (F. A. C. Weber) Byles & Rowley (=Xiquexique gounellei (F. A. C.Weber) Lavor & Calvente), found in 11 studies, and Tacinga inamoena (K. Schum.) N. P. Taylor and Stuppy in 10 studies. More than 50% of the species recorded appeared only once in the lists.

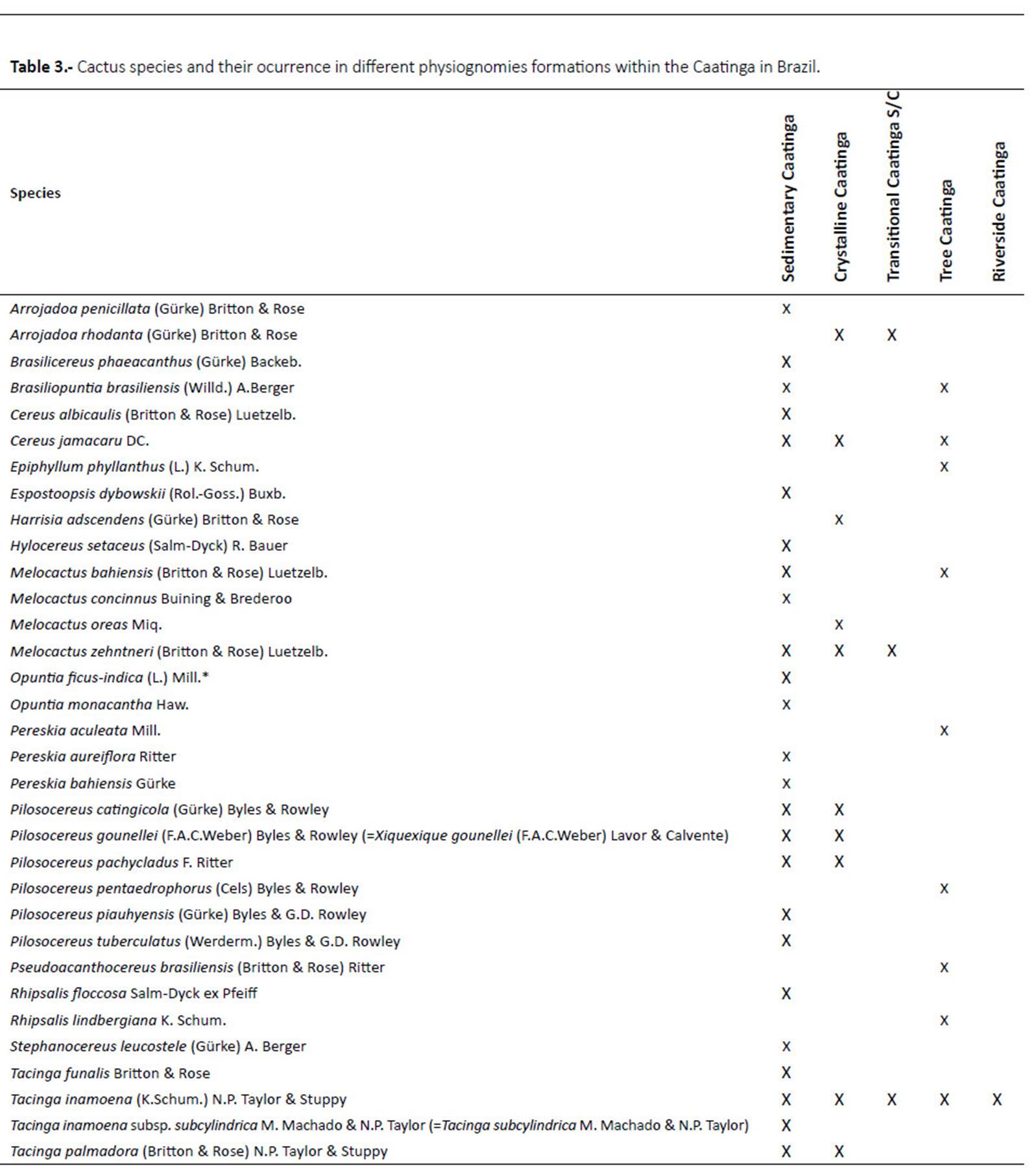

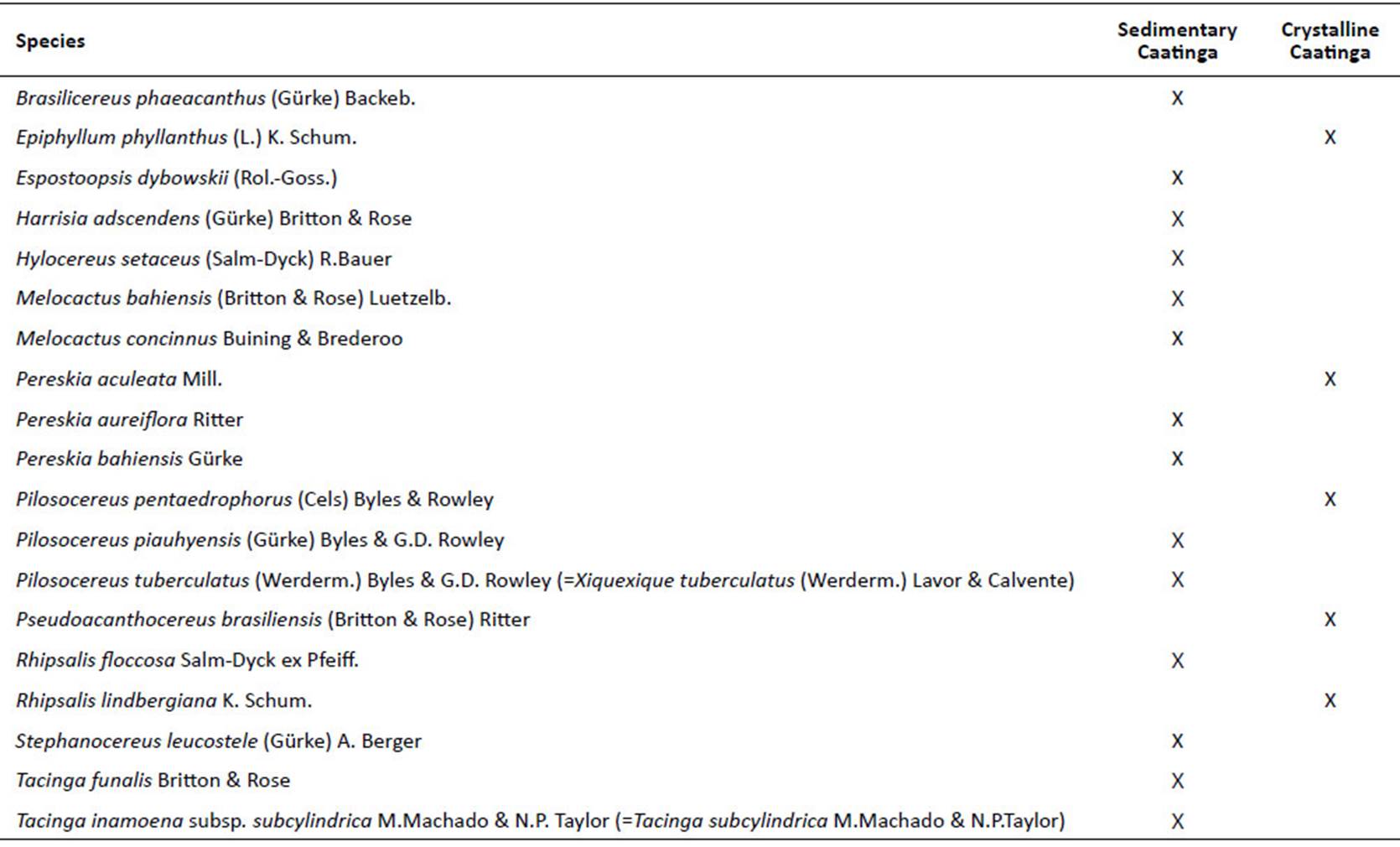

Twenty-five species occur in sedimentary soils, while 10 species occur in crystalline soils of Caatinga. Three species were registered in the transition area, nine species in tree Caatinga and one in Caatinga ripária (or riverine Caatinga) (Table 3).

Table 2 Absolute density of Cactaceae from 24 areas from the Caatinga in Brazil. UC: Conservation unit; ND: Desertification nucleus; AA: Anthropic area; CA: Conserved area. * Material determined as P. grandifolia, however this species does not occur outside the Atlantic Rainforest, thus was left as indetermined. ** Indetermined specimen in the original paper that was identified using the online herbarium ASE.

It was possible to observe the occurrence of species exclusive to the Caatinga physiognomy, with 15 species exclusive to the areas of sedimentary soil and five species exclusive to crystalline soils (Table 3). Only Tacinga subcylindrica M. Machado & N. P. Taylor was common in all four physiognomies of the Caatinga. Meanwhile, Cereus jamacaru, Pilosocereus gounellei (=Xiquexique gounellei) P. pachycladus, P. catingicola, Tacinga inamoena, T. palmadora and Melocactus zehntneri were found in both sedimentary and crystalline soils.

Two cactus species, which appeared in floristic surveys, are found in the Red List of flora threatened by extinction (Table 2, Martinelli & Moraes 2013), the Bahia endemic Espostoopsis dybowskii (EM), and Pereskia aureiflora (VU) from Northern Minas Gerais and Bahia. The later was registered in "Contendas do Sincorá National Forest" (Flona CS), while E. dybowskii was recorded just at the boundary of the Flona CS (Peixoto et al. 2016, Vitório et al. 2019). Apart from these two species, the IUCN (2020) lists Pseudoacanthocereus brasiliensis (VU), while Martinelli & Moraes (2013) classify this species as DD for the Brazilian Red List of Plants. Espostoopsis dybowskii and Arrojadoa marylaniae Soares Filho & M. Machado are also included in the official list of threatened endemic plant species of Bahia state (Secretaria do Meio Ambiente BA 2017).

Floristic similarity analysis

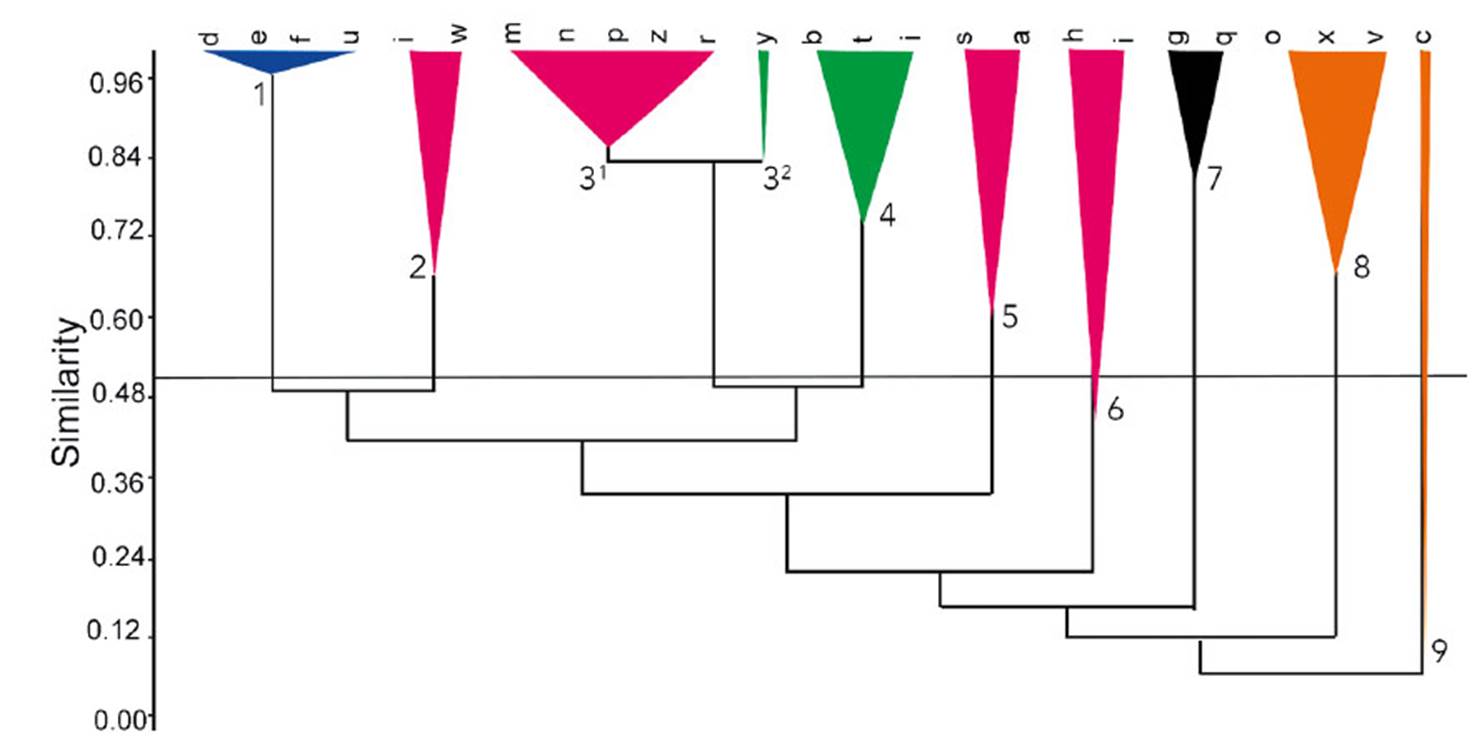

The cophenetic correlation coefficient from the similarity data established among different areas of Caatinga was estimated at 0.843. The clustering analysis resulted in the formation of 10 groups (Figure 2). The clusters were somewhat related to the type of phytophysiognomies defined in Table 3, and only one group did not show similarities with the rest (group 8), being formed by wooded areas strongly influenced by the presence of Brasiliopuntia brasiliensis. Group 1 included areas that occur in different types of formation, such as sedimentary, crystalline, and arboreal surfaces. Group 2, 3¹, 5, 6 and 7 include all areas of sedimentary formation (Fig. 2). Group 7 is the area of Caatinga in the Flona of CS, the only study of Caatinga represented by a floristic survey with Cactaceae as its focus and also the only study with ecological data about cactus populations (Peixoto et al. 2016, Ribeiro-Silva et al. 2016).

Areas located on crystalline formations are found in groups 4 and 3² (Fig. 2). The areas of tree Caatinga can be found within group 8, and group 9 and 10 consist of areas of transition between sedimentary/crystalline with one branch in group 9 belonging to an area of riverside Caatinga.

Density of Cactaceae species in the Caatinga

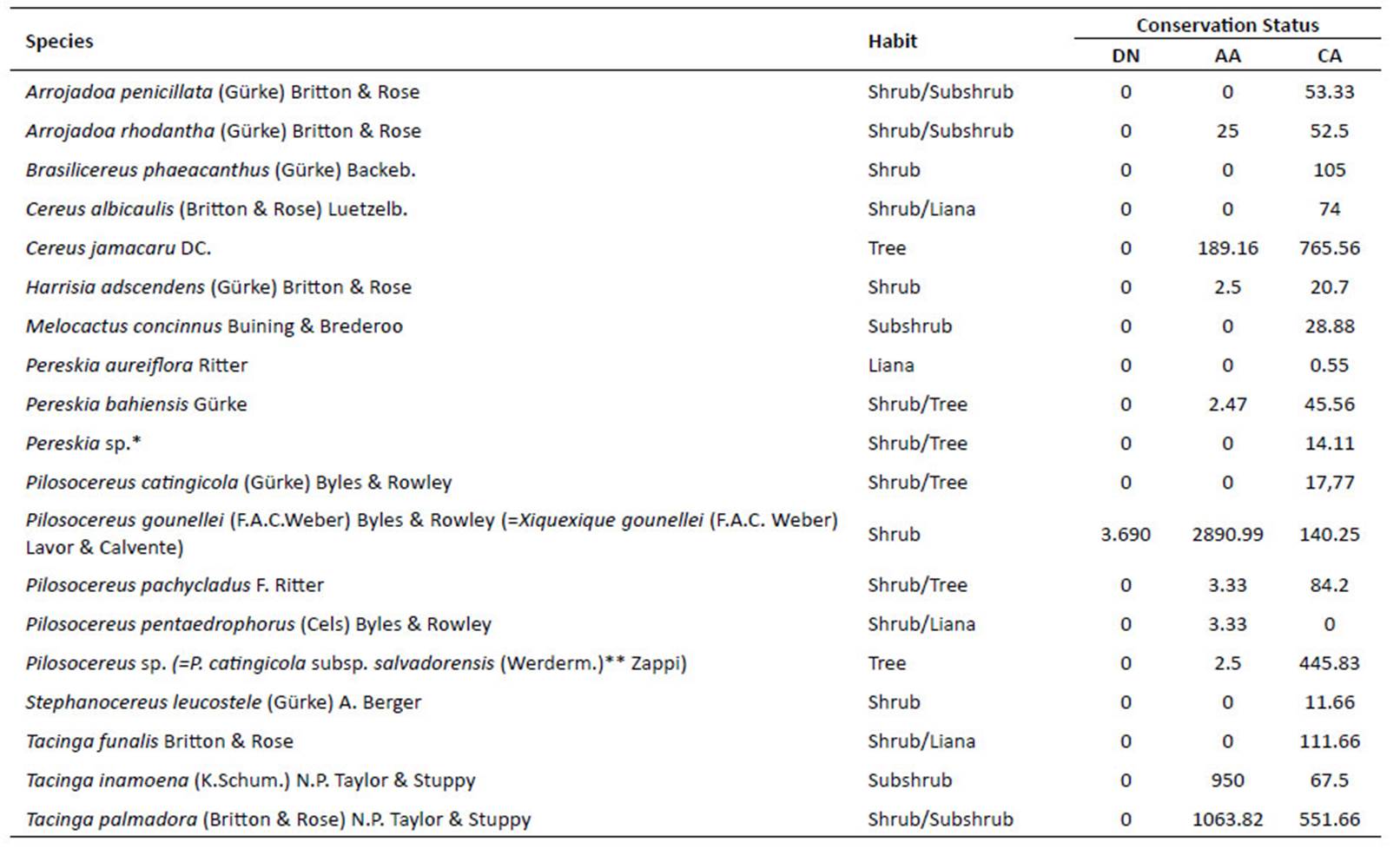

The total absolute density of Cactaceae is 8,037.65 ind.ha-1 . Divided by the 112 species records this generates an average of 73.07 ind.ha-1 of Cactaceae in 24 phytosociological studies. These individuals belong to 20 species and are distributed in 10 genera. Pilosocereus gounellei (=Xiquexique gounellei) was the species with the largest absolute density with 3034.93 ind.ha-1, followed by Tacinga palmadora with 1333.52 ind.ha-1, whilst Pereskia aureiflora is the species with the lowest density at 0.55 ind.ha -1. In relation to the number of species, the most representative genera were Pilosocereus (4 sp.), Tacinga and Pereskia (3 sp. each). The structural data shows that all the areas analysed predominantly present species from shrubby habitats (Table 2).

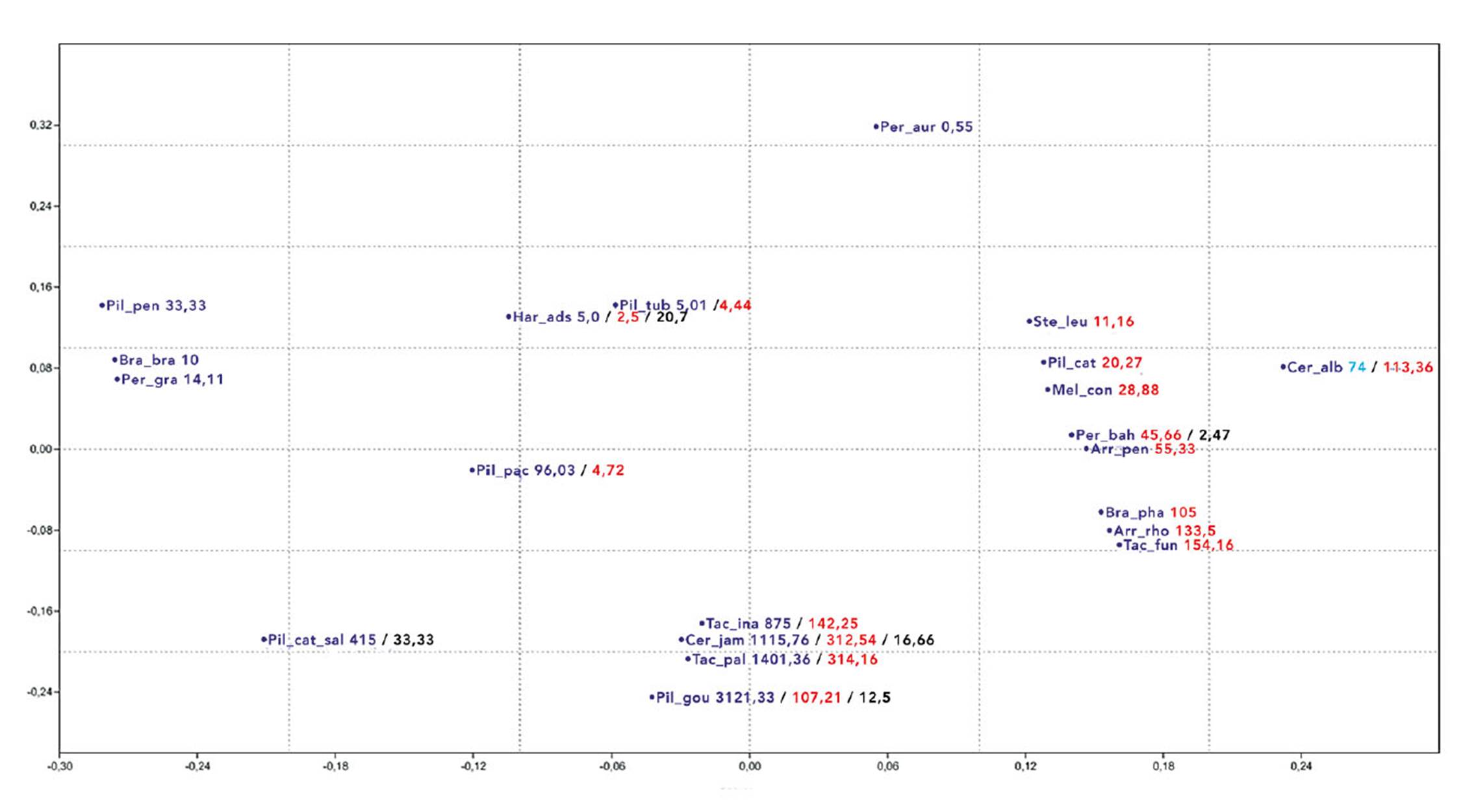

The cluster analysis evidenced separation of species according to a sedimentary substrate gradient, crystalline, transitional, riverside Caatinga and tree Caatinga with the following values for the axes: Axis 1: 35% and in Axis 2: 29% (Figure 3). The analysis demonstrated a gradation between the crystalline and the sedimentary environment, where a larger diversity of Cactaceae species was evidenced in sedimentary Caatinga areas (Table 4).

Figure 2 Similarity analysis of cacti grouping Caatinga types on different substrate (blue group (1): Caatinga with variable substrates, pink group: (2, 31, 5 and 6) sedimentary Caatinga, green group (32 and 4): crystalline Caatinga, black group (7): woody Caatinga and orange group (8 and 9): sedimentary/crystalline transitional Caatinga including a branch of riverside Caatinga). d= Lima et al., 2009; e= Costa et al., 2007; t=Ferraz et al., 1998; Santos et al., 2007; i= Costa et al., 2015; w=Rodal et al. , 1999; m= Silva and Silva, 2012; n= Souza et al., 2015; p= Farias et al., 2017; z= Lacerda et al., 2005; r= Ferreira et al., 2015; y= Araújo et al., 2010; b= Costa et al., 2009; f= Silva et al., 2013; j= Costa et al., 2015; s= Mendes and Castro, 2020; a= Rocha et al., 2004; h= Machado et al., 2012; l= Peixoto et al., 2016; g= Cardoso and Queiroz, 2008; q= Cardoso et al., 2009; o= Lemos and Meguro, 2010 Lemos and Meguro, 2010; x= Souza and Rodal, 2010; v= Silva et al., 2009; c= Pinheiro et al., 2010.

Figure 3 Non-metric multidimensional scaling based on absolute density of cactus species occurring in Caatinga areas on different substrate (crystalline, sedimentary/crystalline transition, sedimentary basin, tree Caatinga and riverside Caatinga).

Table 4 Cactus species that are exclusive of different Caatinga geomorphologic formations in Brazil. Transitional, tree Caatinga and riverside Caatinga had no exclusive species.

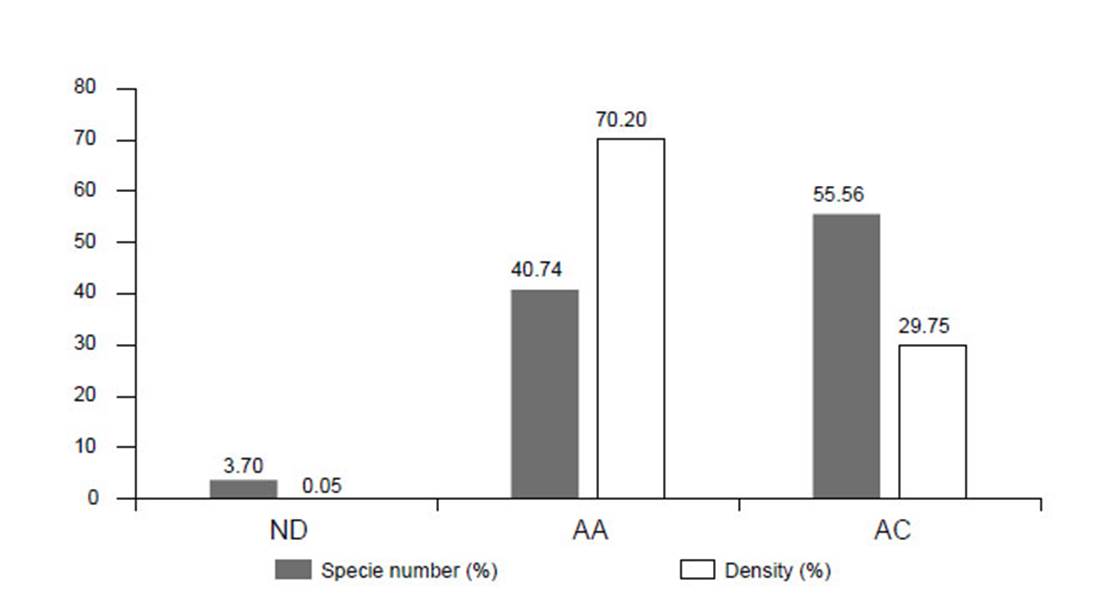

Figure 4 Species number and individual density of cacti in Caatinga areas of different conservation. ND: Desertification Nucleus, AA: Anthropic Area, AC: Conservation Area.

The desertification area presented the lowest number of species, with only Pilosocereus gounellei (=Xiquexique gounellei), and an absolute density of 3.69 ind.ha-1. The anthropic areas presented 10 species, the majority of which with low densities, although some species are more abundant, mainly those that present vegetative propagation, such as: Pilosocereus gounellei (=Xiquexique gounellei) with absolute density of 2890.99 ind.ha-1, Tacinga palmadora, 1063.82 ind.ha-1, Tacinga inamoena, 950 ind.ha-1 and Cereus jamacaru 189.16 ind.ha-1 (Figure 4, Table 2).

The preserved areas presented the higher species richness, with 18 recorded species. Here, the species with the highest absolute density was Cereus jamacaru 765.56 ind.ha-1, Pilosocereus catingicola subsp. Salvadorensis 445.83 ind.ha-1, Tacinga palmadora, 551.66 ind.ha-1. (Fig. 4, Table 2). Pilosocereus gounellei (=Xiquexique gounellei) was the most common species, occurring in all the analysed areas. In contrast, Pilosocereus pentaedrophorus was only recorded in the anthropic zone. Out of the species surveyed in the phytosociological studies, eight are endemic to the Caatinga (T. palmadora, T. inamoena, H. adscendens, T. funalis, P. bahiensis, C. albicaulis, S. leucostele and P. aureiflora) and one (P. aureiflora) is categorized as VU in the plant Red List (Martinelli & Moraes 2013).

Discussion

Although the Caatinga vegetation presents a considerable richness of Cactaceae species, with 122 species, 63 of which are endemic (Zappi & Taylor 2020), only 28% of these species were sampled in floristic studies and 15.57% in phytosociological studies. It is worth noting that only one study investigates exclusively floristic and structural aspects of Cactaceae populations (Ribeiro-Silva et al. 2016). Investigating how these species are distributed in different types of Caatinga is important to understand the family distribution pattern and to verify whether the soil type in different Caatinga formations determines the occurrence of Cactaceae. In the case of Cactaceae, the crystalline formations were the environment where species best established themselves, as seen from the NMDS analysis presenting the highest absolute density. This type of formation represents the largest part of Brazilian semi-arid region and its geology was due to erosion processes during the Tertiary period exposing the pre-Cambrian gneissic basement of the region. This formation generally presents shallow, rocky soils, that are rich in nutrients (Ab'Sáber 1974, Pinheiro et al. 2010, Araújo et al. 2011, Marques et al. 2014, Moro et al. 2016). Although the crystalline areas present higher density for the family, it was the sedimentary environments, characterised by deeper soils, with higher capacity for water retention, that showed the largest diversity of Cactaceae species. This diversity can be attributed to environmental factors such as: rainfall, temperature, and physico-chemical composition of the soil, favourable to the occurrence of a higher number of species (Fraga et al. 2012, Moro et al. 2016).

In riverside Caatinga, the NMDS analyses and similarity are associated with species occurring in crystalline environments. Moro et al. (2016) incorporate these areas as subtypes of crystalline Caatingas, as these environments are found in the same ecoregions and present affinity with the crystalline basement. The tree Caatinga has only one representative common to the sedimentary formation, Pereskia bahiensis, and it does not form a relation to any other group. The genus Pereskia is a basal group within Cactaceae, with little succulence and deciduous leaves in the dry season. The adaptations of P. bahiensis to the semi-arid region are comparable to those of other shrubby, non-succulent genera, so it is not surprising that this species presents less of an affinity with the rest of Cactaceae in terms of its habitat and may also occur in sedimentary as well as in tree Caatinga.

The similarity analysis of NMDS based on the distribution of Cactaceae reinforces Queiroz (2006), Costa et al. (2015) and Moro et al. (2016) regarding the idea that the Caatinga, despite representing a core of dry forest, consists of a varied biota, and should not be treated as a homogeneous vegetation unit. Cactaceae species are good markers for the phytophysiognomy of the Caatinga appearing in all the studied areas. In general, there have been species of Cactaceae associated with both crystalline and sedimentary formations. This is the preponderant factor in the clusters, even higher than the geographic proximity, as distant areas were grouped based on the substrate (Fig 2 , 3).

Concerning the level of conservation of the species among human disturbed areas, preserved areas and the desertification core, there is a pattern between preserved areas and richness, and an indirect relation between density and the number of species. The results are in agreement with the floristic surveys completed for areas of Caatinga, where the anthropic areas present a larger dominance of few species, a smaller diversity of species and lower density (Fig. 4). In the case of Cactaceae, the species that present the strongest dominance are characterised by presenting an elevated rate of propagation, relying on both vegetative and seed propagation (Meiado 2012, Nascimento et al. 2015).

The desertification core includes only Pilosocereus gounellei (=Xiquexique gounellei), a species typical of open, barren environments, able to dwell in soil as well as rocky substrate, with high capacity to propagate both vegetatively and through seeds, which can explain its occurrence in an adverse environment (Taylor & Zappi 2004, Nascimento et al. 2015).

These results corroborate that better preserved environments tend to present larger species richness with a stable population (Magurran 2006, McGill et al. 2007). Diverse factors interfere with the pattern of species density and diversity, such as temperature, rainfall indexes, soil properties, pollination and dispersal, production of viable seeds and human interference (Peters 2002, Salo 2004).

It is worth emphasizing that, from the species listed, Pilosocereus gounellei (=Xiquexique gounellei), Tacinga inamoena, T. palmadora and Cereus jamacaru are the species most often utilised by the local community of the Caatinga, mainly for feeding livestock and for wood (Andrade et al. 2006). According to the residents of these areas, in the past, the density of Cactaceae individuals was higher (Lucena et al. 2015). Duque (2004) also mentions the use of Cactaceae by rural people, particularly during periods of prolonged drought, highlighting that there is no sustainable management of these species and that the lack of replanting can lead to the diminishing of less robust or uncommon species.

Conclusion

Both floristic and phytosociological studies that include Cactaceae carried out in areas of Caatinga agree with the idea proposed by Queiroz (2006), whereby the Caatinga shows a distinct biota from other rainforest cores.

Cactaceae are a good marker to distinguish patterns within the Caatinga. Caatinga on sedimentary substrate is richer in cactus species, while crystalline substrate supports a few exclusive species, such as Pilosocereus pentaedrophorus and Pseudoacanthocereus brasiliensis.

Some species display similarities with other areas of Caatinga despite being geographically distant (e.g. Harrisia adscendens for crystalline areas). Also species found to form distinct groups between the crystalline and sedimentary Caatinga, with different composition, serve as evidence that these two environments represent distinct floristic formations.

The absence of several flagship species, some of which are rare, such as Arrojadoa marylaniae, or threatened (e.g. Melocactus conoideus, M. azureus, M. ferreophilus, M. pachyacanthus), from any of these lists is likely due to their occurrence on bare rock or rock crevices, areas rarely sampled by the type of phytosociological studies used for the present work. In the present work, this limitation is also reflected in the lack of information regarding mining (the main human disturbance faced by the rocky habitats), suggesting that more work must be devoted to the floristic and phytosociological study of rock outcrops on gneissic, quartzitic and limestone outcrops in the region.

Floristic and phytosociological data are important for the outlining of new priority areas for conservation of Cactaceae and representative areas of the Caatinga. Species restricted to certain environments are at risk of extinction, especially if the species are already vulnerable. The fact that these species are not present or are at very low densities in the anthropogenically disturbed areas, emphasizes the importance of maintaining natural areas.

On the other hand, certain species remain abundant, in disturbed areas, such as as Tacinga palmadora, T. inamoena, Cereus jamacaru and Pilosocereus gounellei (=Xiquexique gounellei), likely as a result of the type of reproduction exhibited by those taxa

uBio

uBio