Introduction

Species coexistence inside a community has been attributed to ecological factors (competition and predation; Schoener 1974, 1975); however other explanations are suggested: morphological differences and physiology (Chase et al. 2002), foraging mode (Huey 1979), reproduction patterns (Colli et al. 1997), allopatric characteristics (Huey & Pianka 1977, Huey 1979), among others. Based on its historic context (phylogeny), these species should present differences due to their evolutionary history rather than competitive pressures (Huey 1979, Vitt et al. 1999, Losos 2000, Pérez 2005). Otherwise, recent studies demonstrated that differential partitioning of biotic and abiotic resources is the principal factor for community structure (Mesquita & Colli 2003, Mesquita et al. 2006), overall, on areas where resources are scarce (Pérez 2005, Jordán 2010).

Usually, species partitioned their resources over three dimensions of the ecological niche: temporal, spatial and trophic niche. So, species differs in their activity patterns, spaces where they exploit resources and prey consumption allowing the coexistence of several species on a community (Hutchinson 1957, MacArthur 1972, Pianka 1973, Dunham 1980, 1983, Vitt et al. 1999, Vanhooydonck et al. 2000).

Lizard species are “ideal models” for ecological research because they display several characteristics (i.e. thermoregulation, high site fidelity, low dispersal rate, territorial behavior) that had been well studied (Cowles & Bogert 1944, Pianka 1973, Huey & Pianka 1981, Huey et al. 1983, Vitt & Pianka 1994, Vitt et al. 1999, 2003). Lizard resource use patterns have been studied widely in Australian desertic ecosystems (Pianka 1973, Huey & Pianka 1977, Pianka 1986, Vitt 1991) while research on interactions inside lizard community structures had been increasing on Neotropical ecosystems (Colli et al. 1992, Vitt& Colli 1994, Vitt & Zani 1998, Vitt et al. 1999, Mesquita & Colli 2003, Mesquita et al. 2006, Rocha et al. 2009) specially on Teiids and Tropidurids in Central and South America (Rocha & Bergallo 1990, Vitt & Colli 1994, Vitt & Zani 1998, Faria & Araujo 2004, Rocha et al. 2009, Ribeiro 2010).

The tropidurids lizards Microlophus occipitalis (Peters 1871) and Stenocercus puyango (Torres-Carvajal 2005) are distributed on northwestern Peru and southwestern Ecuador, using a broad variety of habitats as rocky boulders, bushes, and algarrobo trees (Prosopis sp.) (Dixon & Wright 1975, Torres-Carvajal 2005). Regardless of their broad distribution range (Carrillo & Icochea 1995, Torres-Carvajal 2005, 2007), few studies consider ecological traits for both species (Watkins 1996, 1997, 1998, Jordán & Pérez 2012) which occupy in syntopy a narrow area inside Cerros de Amotape National Park.

Cerros de Amotape National Park holds the most important ecoregions of northwestern Peru: Equatorial Dry Forest and Pacific Tropical Forest (Brack-Egg 1986), showing a high endemism rate and connectivity for wildlife between both ecosystems (SERNANP 2012), and had been considering a “biodiversity hotspots” (“TumbesChocó-Magdalena”; Mittermeier et al. 2005). Regardless of these characteristics, few herpetological studies had been done inside this protected area (Tello 1998, Jordán 2006, 2010, 2011a, 2011b, Jordán & Pérez 2012). The goal of this study is to analyze differences or similarities at the temporal, spatial, trophic niche, and thermal characteristics between Stenocercus puyango and Microlophus occipitalis which allows them to coexist in syntopy in Cerros de Amotape National Park.

Material and methods

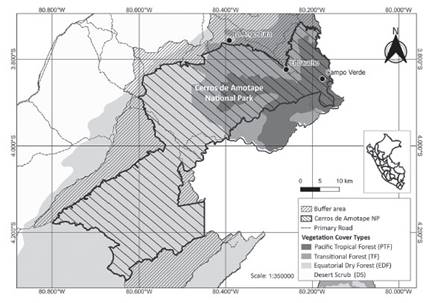

Study area.Data collection was done between El Caucho and La Angostura localities (Fig. 1) in the transitional area of the Pacific Tropical Forest and the Dry Forest inside Cerros de Amotape National Park (PNCA) in the northwestern region of Tumbes (SERNANP 2012) between August and September of 2012. The climate is relatively mild with an average annual temperature of 26 °C showing a highly marked seasonality with a dry season ranging from May to November and a wet season ranging from December to April with an annual average precipitation of 1450 mm (Ponte 1998).

Figure 1 Study area located between La Angostura and El Caucho localities inside Cerros de Amotape National Park.

ata Collection.Data were collected by three herpetologists (360 man-hours) during 20 days at the dry season through visual encounter surveys (VES) (Crump & Scott 1994) with 30 minutes duration between 08:00 and 18:00 hours.

Activity pattern and thermal ecology.For each observed individual, sighting hour was recorded and a histogram was elaborated from this data. A KolmogorovSmirnov test was used to determine possible differences in activity patterns for each species. Body, air, and substrate temperatures (°C) were registered for each captured individual after Vitt & Carvalho (1995). Temperatures were recorded with a cloacal thermometer Miller and Weber® to the nearest 0.2 °C. The relationship between body and environmental temperatures were analyzed by simple and multiple regressions as well as differences in temperatures for age, sex, and species with a variance analysis (ANOVA). The exposure degree to the sun (exposed: totally exposed to sunlight; filtered: exposed to scattered sunlight; shaded: under total vegetation cover) for each observed individual were registered and analyzed with an ANOVA with exposure degree as factors (Vitt et al. 1995).

Microhabitat Use. Eight microhabitats categories were identified in the study site for the study species: leaf litter (substrate covered by leaf litter totally), soil (substrate without leaf litter), (3) gravel (<5 cm), (4) sand, (5) tree branches, (6) trunks, (7) vegetation (crawling, herbs, shrubs), and (8) stones (>5 cm). Potential differences in microhabitat use between age, sex, and species were assessed with a Chi-square test.

Diet. All captured lizards were sacrificed immediately with Halatal® and preserved on 70° alcohol. Stomachs were dissected and analyzed under a stereomicroscope identifying prey items to order level (including broad categories as insect larvae). A Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine differences in diet composition consumed by lizard species.

Niche breadth.We compute niche breadth (spatial, temporal, and trophic) using the inverse of Simpson’s diversity index formula of Simpson (Simpson 1949, Pianka 1973, Vitt & Zani 1996:

Niche breadth value range from 1 to n, where low values indicate a restricted use of resources while high values indicate an intensive use (Vitt & Zani 1996). The overlapping degree of the spatial, temporal and trophic niche was evaluated with the symmetric overlap index (Ф ) where values near to 0 indicate a low overlap while values near or equal to 1 indicate a high overlap on the resource used (Pianka 1973, 1986):

We generated 1000 repetitions using EcoSim 700 software (Gotelli & Entsminger 2004) and comparing “real” data matrix (observed) with “simulated” matrix (simulated) through a Monte Carlo analysis using R3 algorithm (Pianka 1973, 1986) to determine if overlap on any niche dimension (trophic, spatial, temporal) is a real structure or a random result (Winemiller & Pianka 1990, Gotelli & Entsminger 2004, Rouag et al. 2007). The recommended R3 algorithm retains niche breadth (or specialization degree) of each species in the simulated matrices but “allow” the potential use of other unexploited resources (Winemiller & Pianka 1990, Gotelli & minger 2004, Rouag et al. 2007).

Statistical analysis. We used PAST ® Version 3.0(Hammer et al. 2001) with a significance level (α) ≤ 0.05 for statistical analysis. Normality was verified through an Anderson-Darling test before parametric or non-parametric statistics were applied; variance homogeneity was analyzed with the Levene test. Data means appear ±1 SD in text. All collected individuals were deposited on the Department of Herpetology, Natural History Museum, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos.

Results

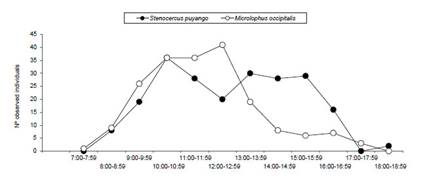

Activity pattern.A total of 408 sightings of both species Stenocercus puyango and Microlophus occipitalis (Fig. 2) were registered between 8:00 and 16:00 hours (216 and 192 respectively).

Figure 2 (a) Microlophus occipitalis (adult male) and (b) Stenocercus puyango (adult male) in Cerros de Amotape National Park.

A higher proportion of Stenocercus puyango sightings (52.9%) were registered between 10:00 and 15:00 hours while 47.1% of Microlophus occipitalis sightings were registered between 10:00 and 13:00 hours (Fig. 3). No significant differences between activity patterns for both species were registered (D =0.18, p>0.05), indicating both species exhibit a unimodal activity pattern.

Figure 3 Activity pattern of Microlophus occipitalis and Stenocercus puyango in Cerros de Amotape National Park.

Thermal ecology.Average body temperature of Microlophus occipitalis was higher than Stenocercus puyango average body temperature as well as the related environmental (air and substrate) temperatures (Table 1). Body temperatures of each species differ significantly (F =35.84; p<0.05), indeed air (F =5.28; p<0.05) and substrate temperatures (F =10.32; p<0.05).

Table 1 Body temperature (Tb), air temperature (Ta) and substrate temperature (Ts) recorded for both species in Cerros de Amotape National Park. Mean ± standard deviation and range are showed.

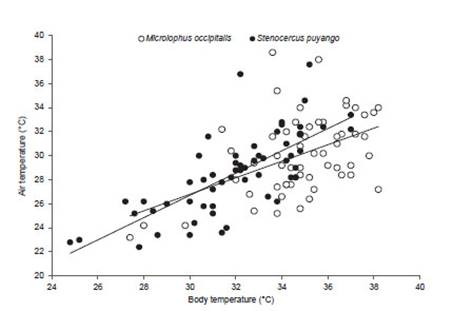

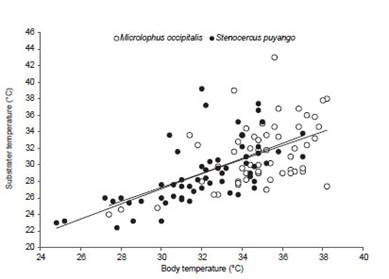

Body temperature of Stenocercus puyango was significantly related with air temperature (T ) (R2=0.53, F(1,57) =66.88, p<0.05, n=58) and substrate (Ts ) (R2=0.42, F =40.83, p<0.05, n=58) (Figure 4 and 5). Also, body temperature of M. occipitalis was significantly related with air temperature (R2=0.22, F(1,55)=15.57, p<0.05; n=56) and substrate (R2=0.24, F(1,55)=17.9, p<0.05; n=57) (Figs. 4 and 5).

Figure 4 Relationship between body and air temperature of Mi Microlophus occipitalis (R2=0.22, F(1,55)=15.57, p<0.05; n=56) and Stenocercus puyango (R2=0.53, F(1,57)=66.88, p<0.05, n=58).

Figure 5 Relationship between body and substrate temperature of Microlophus occipitalis (R2=0.24, F(1,55)=17.9, p<0.05; n=57) and Stenocercus puyango (R2=0.42, F(1,57)=40.83, p<0.05, n=58).

Multiple regression showed that environmental temperatures (Ta and Ts) influenced significantly over body temperature of Stenocercus puyango (R2=0.52; F =29.55; p<0.05; n=58) and M. occipitalis (R2=0.23; F =8.96; p<0.05; n=57).

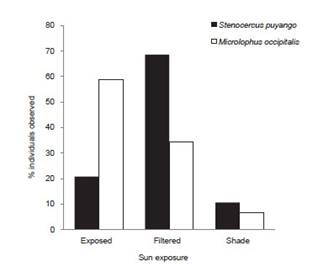

A higher proportion of Stenocercus puyango was registered under filtered sun (n=148, 68%) follow by individuals exposed to sun (n=45, 21%) and shade (n=23, 11%), while M. occipitalis was recorded exposed to sun (n=113, 59%), and a lower proportion under filtered sun (n=66, 34%) and shade (n=13, 7%) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6 Exposure degree to sun of Microlophus occipitalis and Stenocercus puyango in Cerros de Amotape National Park.

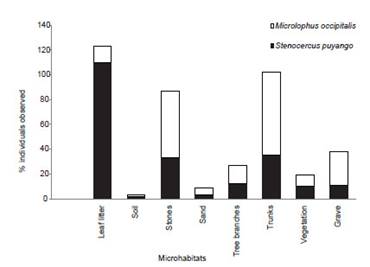

Microhabitat use.Leaf litter was the most used microhabitat by S. puyango (n=216) (50.9% of all records) followed by trunks and stones (16.2% and 15.3%, respectively; Fig. 7). Individuals of M. occipitalis (n=192) were registered on trunks (34.9%), stones and grave (28.13% and 14.06%, respectively). Significant differences were found in microhabitat use among the eight identified categories by S. puyango and M. occipitalis (x2=155.78, p<0.05). Spatial niche breadth (Bs) for S. puyango and M. occipitalis were 2.49 y 3.39 respectively.

Figure 7 Microhabitat use of Microlophus occipitalis and Stenocercus puyango in Cerros de Amotape National Park.

Diet. Diet of S. puyango (n=55) and M. occipitalis (n=60) was composed of 17 and 15 different types of prey items, respectively (Table 2), where hymenopterans and insect larvae were the most consumed prey items by both species.

Table 2 Diet composition of Microlophus occipitalis (N= 55) and Stenocercus puyango (N= 60) in Cerros de Amotape National Park. N-number of prey items; %N-percentage of prey items consumed, Ffrequency of prey items in stomachs, %Fpercentage of prey items frequency.

Stenocercus puyango consumed hymenopterans (26.58%), orthopterans (12.96%), coleopterans (10.63%), and hemipterans (8.64%), and a higher percentage of insect larvae (21.26%) both in frequency and numerically. Predominant preys in M. occipitalis diet were hymenopterans (33.33%), coleopterans (12.64%), orthopterans (9.2%), and elevated consumption of insect larvae (30.27%) with similar results in frequency (Table 1). Significant differences in numerical diet composition between both species were not found (D max=0.18, p>0.05).

Niche breath and niche and overlap.Stenocercus puyango showed a wider temporal niche breadth (Bt ) than M. occipitalis (Bts=8.28 and Btm=6.65, respectively) and the temporal niche overlap (Φjk) between both tropidurids was higher (Φjk=0.84; p obs ≥ esp= 0.01) (Table 2). Spatial niche breadth (Bs) was wider for M. occipitalis (Bsm=4.26) than S. puyango (Bss=3.15), however, both species showed a lower overlap on this niche axis (Φjk=0.54; p obs ≥ esp= 0.001) (Table 3). Otherwise, trophic niche breadth was wider for Stenocercus puyango than for M. occipitalis (Bds=6.26 and Bdm=4.35, respectively), with a higher trophic niche overlap (Φjk=0.96; p obs ≥ esp = 0.001).

Table 3 Niche breadth and niche overlap between Microlophus occipitalis and Stenocercus puyango. Bt: temporal niche breadth. Bs: Spatial niche breadth. Bd: trophic niche breadth.

The values of the null modes (p observed ≥ simulated) were lower than the significance level established (p>0.05) indicating the existence of a real structure for each ecological niche dimension for these lizard species.

DISCUSSION

Microlophus occipitalis and Stenocercus puyango showed a higher overlap on the temporal and trophic niche and lower overlap in spatial niche; in other words, they are active at the same hours and feeding on similar prey items, while the greater difference was observed on the spatial niche.

Ecological similarities such as their heliophilic and diurnal habits of both species may be related to their evolutionary similarity since both belongs to Tropiduridae lizard family (Bergallo & Rocha 1993, Rocha et al. 2009) and reflecting the wide temporal niche breadth of both species, as well as their high temporal overlap.

Diurnal activity patterns attributed to sunny hours for both species could be related to their thermal demands (Hatano et al. 2001), allowing them to develop their ecological activities (Bauwens et al. 1996, Smith & Ballinger 2001). This same diurnal activity pattern with a midday activity peak had been reported for other tropidurid species in the Peruvian coastal desert (M. peruvianusHuey 1974, Catenazzi et al. 2005, Pérez & Balta 2007, M. tigris-Pérez 2005, Jordán 2011, M. theresiae and M. thoracicus-Pérez & Balta 2007).

A similar activity pattern, reflected by a high temporal niche overlap, may be an important factor for similar diet composition for both sympatric species because they could be exposed to the same preys set, explaining the high trophic niche overlap. This similarity on prey consumption could be related to seasonality (dry season diversity related to limited availability of resources (vegetation) pushing lizards to prey over a similar and limited set of arthropods and other items. Ribeiro & Freire (2011) reported a similar case where a high trophic niche overlap was registered during the dry season between two tropidurid species (Tropidurus hispidus and T. semitaeniatus) in northeastern Brazil.

Foraging mode could influence diet similarity for both species. Lizards exhibiting an ambush foraging strategy eats mobile preys while active foraging lizards eats sedentary preys (Huey & Pianka 1981). phus occipitalis and S. puyango showed an arthropodbased diet, a basal condition for Neotropical lizards (Vitt et al. 2003), where ants (Formicidae) and insect larvae were the more abundant and frequent consumed preys. The high mobile preys consumption should be related to their foraging mode (sit and wait foragers, Schoener 1971) however a significative proportion of insect larvae, a low/mobility preys, were found on stomachs. This result reflects an intermediate foraging mode dependent of prey item availability in their environment as had been pointed by Huey & Pianka (1981) for lizards and reported by other authors in tropidurines (Bergallo & Rocha 1993, Pérez 2005). A similar pattern was found by Ribeiro & Freire (2011) for Tropidurus hispidus and T. semitaeniatus diet in northeastern Brazil and Meira et al. (2007) in central Brazil for T. oreadicus, were a mixed diet composed by active (Formicidae and Orthoptera) and lumped or sedentary items (termites and insect larvae) were registered. This plasticity in foraging mode probably allows Stenocercus puyango and Microlophus occipitalis to eat a wide variety of prey items, saving time and energy intake while preying (Ribeiro 2010). Both species showed a wide trophic niche, like other peruvian tropidurid species, indeed occupying distinct habitats as beaches (Microlophus peruvianus, Quispitúpac & Pérez 2008), lomas (or foothills, Microlophus tigris, Pérez 2005) and desert (Microlophus theresiae, Pérez & Balta 2007). Thus, S. puyango and M. occipitalis could be considered as generalist predators. However, Chávez-Villavicencio et al. (2018) reported a narrow niche breadth for Microlophus occipitalis (B =0.13) explained by a high consumption of ants, ar 58.9 % compared to the 26.6% of this study and a lower consumption of other items. This could be related to prey abundance and vegetation composition among sites where the study site of Chavez-Villavicencio et al (2018) considered as “algarrobal” shows a minor vegetation complexity than the tropical dry forest in Tumbes.

Differences in microhabitat use could be related to specific thermal demands of each species, selecting microhabitats with favorable thermal characteristics. Both species in this study showed significant differences in body temperature, where M. occipitalis showed a higher body temperature (Jordán & Pérez 2012), indicating greater thermal needings than S. puyango. Also, environmental (air and substrate) temperatures in M. occipitalis were significantly higher than values recorded for S. puyango, indicating a selection for microhabitats with higher temperatures. Additionaly, Microlophus occipitalis is small lizard with a higher superficial area-volume relationship compared to S. puyango, so is probably this species loss heat at a higher rate, selecting “warmer” areas for thermoregulation at wide time intervals to reach its optimal body temperature.

In this sense, M. occipitalis selects open and sunny patches as microhabitats in the forest for thermoregulation, maintaining higher and stable body temperatures (Jordán & Pérez 2012). On the other hand, S. puyango inhabits inside the forest, selecting filtered-sun microhabitats including fallen tree trunks and leaf litter. Similar results were registered by Dias & Rocha (2004) for two Cnemidophorus (Teiidae) species in northeastern Brazil where differences in microhabitat selection were related to exposure degree and vegetative cover. Thus, thermal environment influences body temperature in lizards (Smith & Ballinger 2001), including complex relationships with physical variables (wind, air and substrate temperature, radiation, etc.) (Tracy 1982, Olivera 2015).

Niche overlap was higher in trophic and temporal axis but lower in microhabitat use relative to the other two axes explaining the coexistence of these two lizard species. Monte Carlo simulations for the three ecological niche axis indicated that overlapping patterns are real (due to phylogeneticsrelated similarities) rather than random.

In conclusion, differences in spatial use between Microlophus occipitalis and Stenocercus puyango would be related to differential resources use, allowing the coexistence of both species in sympatry inside of Cerros de Amotape National Park.

uBio

uBio