Introduction

The Amazon drainage is the largest basin in the world and the major component of the Neotropical region. It includes a vast area of 7.3 million km2, crosses South America from the eastern Andes Mountains to the Atlantic coast crossing the shields of Brazil and Guyana (Venticinque et al. 2016, Leite & Rogers 2013). Besides its vastness in area, the Amazon basin possesses distinct physiognomies formed by geological backgrounds, diversity of rivers and soils (Dagosta & de Pinna 2018); and overall warm and humid Amazonian climate (Leite & Rogers 2013). In turn, these factors are associated with an enormous diversity of flora and fauna, comprising the richest ecosystem on the planet (Dagosta & de Pinna 2019).

The freshwater fish diversity of South America encompasses 5160 species; however, despite already being the most diverse freshwater ichthyofauna, estimates point to actual diversity between 8000 - 9000 species (Reis et al. 2016). The Amazon basin harbors the highest fish diversity in the world with 2406 described species (Jézéquel et al. 2020). Several efforts have been made to describe species and update lists of species by countries (Ortega & Vari 1986, Maldonado et al. 2008, Matamorros et al. 2009, Ortega et al. 2012, Mol et al. 2012, Le Bail et al. 2012, Barriga 2012, Angulo et al. 2013, Koerber & Litz 2014, Sarmiento et al. 2014, Mirande & Koerber 2015, Koerber et al. 2017, DoNascimiento et al. 2017) basins (Lasso et al. 2016, Ohara et al. 2017, Beltrão et al. 2019), regions (Jimenez-Prado et al. 2015, Van Der Sleen & Albert 2017, Dagosta & de Pinna 2019), and states (Bertaco et al. 2016, Dos Reis et al. 2020, Teixeira el al. 2020) along the Neotropical region.

The last checklist of freshwater native fishes from Peru registered 1064 species (Ortega et al. 2012), but with additions of new species, new records and taxonomic revisions, this diversity reached 1141 species (MINAM 2019). Peru is made up of 24 departments and a constitutional province (Callao); however, fish diversity studies were never carried out by department and the main fish checklists were directed to sub-basins, (Ortega et al. 2006, Rengifo 2007, Palacios et al. 2008, Carvalho et al. 2009, Correa & Ortega 2010, Carvalho et al. 2011, Quezada et al. 2017, Armas et al. 2021).

Important ichthyological material deposited in peruvian fish collections comes from fieldwork associated to their environmental impact studies requested by law, to evaluate their potential impacts. In Loreto, some examples of these kind of activities are the exploration, exploitation, processing, and transportation of hydrocarbons (oil, gas) and Hidrovia projects. On the other hand, Rapid Biological Inventories conducted by the Field Museum during last 20 years have made possible to register the diversity from several areas in Loreto, particularly the fishes (Table 1).

Table 1 Previous fish inventories in different basins in Loreto. NP=National Park, NR=National Reserve, RAC=Regional area of conservation.

| Inventories | Total species | Possible new species | Conservation status | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biabo Cordillera Azul | 93 | 10 | NP | de Rham, Hidalgo & Ortega, 2001 |

| Yavarí | 240 | 10 | Ortega, Hidalgo & Bértiz, 2003 | |

| Ampiyacu, Apayacu, Yaguas, Medio Putumayo | 207 | 5 | RAC | Hidalgo & Olivera, 2004 |

| Matsés | 177 | 9 | NR | Hidalgo & Velásquez, 2006 |

| Sierra del Divisor | 109 | 14 | NP | Hidalgo & Pezzi, 2006 |

| Nanay-Mazán-Arabela | 154 | 12 | RAC | Hidalgo & Willink, 2007 |

| Cuyabeno-Güeppí | 184 | 3 | NP | Hidalgo & Rivadeneira, 2008 |

| Maijuna | 132 | 7 | RAC | Hidalgo & Sipión, 2010 |

| Yaguas-Cotuhé | 337 | 7 | NP | Hidalgo & Ortega-Lara, 2011 |

| Cerros de Kampankis | 60 | 6 | Quispe & Hidalgo, 2012 | |

| Ere-Campuya-Algodón | 210 | 4 | Maldonado-Ocampo, Quispe & Hidalgo, 2013 | |

| Cordillera Escalera | 30 | 2 | Hidalgo & Aldea-Guevara, 2014 | |

| Tapiche-Blanco | 180 | 4 | Corahua, Aldea-Guevara & Hidalgo 2015 | |

| Medio Putumayo-Algodón | 232 | 12 | Hidalgo & Maldonado-Ocampo, 2016 | |

| Bajo Putumayo-Yaguas-Cotuhé | 150 | 2 | Faustino-Fuster, Patarroyo & de Souza, 2021 |

Extensive biodiversity in Loreto is not limited to freshwater systems. Pitman et al. (2013) have done the first biodiversity compilation including plants and terrestrial vertebrates. As a result, Loreto has probably the highest species richness among Peruvian Departments, with 7959 plant species, 914 bird species, 267 mammal species, 216 amphibian species and 170 reptile species. Of these, the number of threatened species ranges between 1.7% (plants) to 7.5% (mammals) depending on the groups, and the number of endemics between 0.2% (birds) and 5.5% (amphibian).

In contrast, the knowledge of fish diversity from Loreto is far from complete. By this point, it is an important task to be done. Accordingly, this study aims to provide the first checklist of freshwater fishes recorded in Loreto to improve scientific information for guiding policy and management decisions for conservation and fishery management.

Material and methods

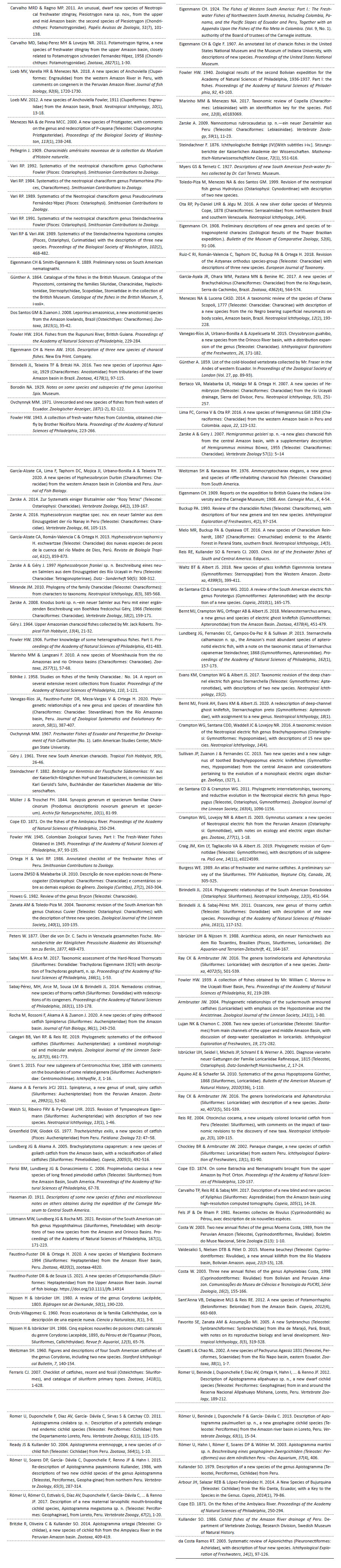

Study area. - Loreto is the largest department in Peru located northeast of the country, representing 28% of the Peruvian territory with an area of 368 851, 950 km2 (CONAM 2005). Its borders are with Ecuador in the northwest, with Colombia in the northeast, Brazil in the east, Amazonas and San Martin departments in the west, and the Ucayali department in the south (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Loreto department showing main tributaries of the Amazon basin, sampling localities (black dots) taken from available databases.

Loreto is part of the Amazon rainforest, belonging to the Amazon Lowland ecoregion (Abell et al. 2008) with remnants of the Andes in the west border, as well as the Cerros del Kampankins (Pitman et al. 2012), Cordillera Escalera (Pitman et al. 2014) and Cordillera Azul (Alverson et al. 2000). In the heart of the department, the Amazon River is formed by the confluence of Marañón and Ucayali rivers, close to Nauta City.

The Marañón River is born in the Andes, in the Raura snow peak in Pasco Department about more than 5800 meters above sea level (m a.s.l.). According to the elevation gradient, the Marañón River can be split into the upper and lower basin. The upper Marañón River flows from the Raura snow peak to the Manseriche Pongo at 190 m a.s.l., and from approximately the middle of this geomorphological zone this river flows crossing the Loreto region. The lower Marañón River comprises Manseriche Pongo as it joins with Ucayali River in Nauta City. The lower Marañón River flows from west to east in the Amazonian lowlands in Loreto, presenting a meandering channel, covered by sand and sparse rocks. During the flood season, it floods extensive areas frequently abandoning its old channel, opening a new one. The abandoned channels form the “cochas” lagoons or ox bow lakes, which - due to the shape they present - are called horseshoe lakes. The main tributaries of the lower Marañón River are Morona, Pastaza, Tigre, and Huallaga rivers (MINAM 2011).

The Ucayali River headwater is in the Eastern Andes, in the Mismi snow peak 5597 m a.s.l. in Arequipa, but is formally named by the junction of Urubamba and Tambo rivers, in the south of Ucayali Department. It can be separated into the upper and lower basin as well. The Upper Ucayali River flows from the Mismi snow peak to confluence between Ucayali and Pachitea rivers. The Lower Ucayali River goes from Pachitea River mouth to the confluence with Marañón River. The lower Ucayali River flows from south to north in Loreto; it also has meandering course forming “cochas” or lagoons and islands which constantly change shape and size. The tributaries of the lower Ucayali River are Aguaytia, Pisqui, Cushabatay and Tapiche rivers (MINAM 2011).

It is worth mentioning that both Lower Marañón and Ucayali rivers are navigable during the year. Once the Peruvian Amazon River is formed, it receives the contribution of tributaries like Nanay, Itaya, Napo, Ampiyacu-Apayacu, and Yavarí rivers (Peru); and Putumayo River (Colombia).

Data collection. - This study was based on bibliographic information. The record of species were obtained from collection data available on iDigBio (https://www.idigbio.org/portal/search), speciesLink (http://www.splink.org.br/) and mainly from Museo de Historia Natural, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima (MUSM) database from fishes sampled in Loreto department.

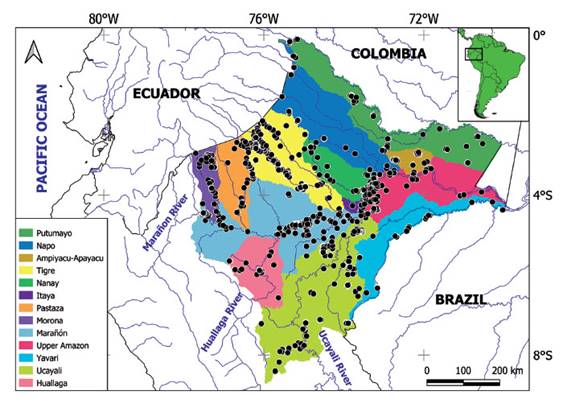

The databases formed belongs to scientific collection, namely Academy of Natural Science of Philadelphia, Philadelphia (ANSP), California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco (CAS), Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago (FMNH), Museu de Ciências e Tecnologia da Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre (MCP), Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, Paris (MNHN), Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge (MCZ), Museo de Historia Natural, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima (MUSM), Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo (MZUSP), University of Florida, Florida Museum of Natural History, Gainesville (UF), University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, Ann Arbor (UMMZ), Museu de Zoologia da Universidade Estadual de Campinas "Adão José Cardoso", Campinas (ZUEC). Doubtful information, like no coordinates localities or unlikely coordinates, were discarded. Additionally, information was also compiled from available literature including species descriptions, taxonomic revision, and fish inventories and checklist (Appendix 1). This compilation covers 262 years of ichthyological information (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 Cumulative curve of fish species described from Loreto department between 1758 - 2020, based on bibliographic information.

The taxonomic nomenclature for order and families follows Betancur et al. (2017); valid names were confirmed following Eschmeyer Catalog of Fishes (Fricke et al. 2021). The use of aff. and cf. were avoided to try to get a precise number of species; in the same way, the use of “sp.” was avoided except by few genera with no more species to represent. Nonnative species recorded from the natural environment in the Loreto department, with or without vouchers in fish collections were considered in a separate list and commented on in the discussion. Commercial species were taken from available information (García-Davila et al. 2018).

The conservation status of each species was taken from the last assessment following the IUCN criteria in 2014 available in https://www.iucnredlist.org/.

Results

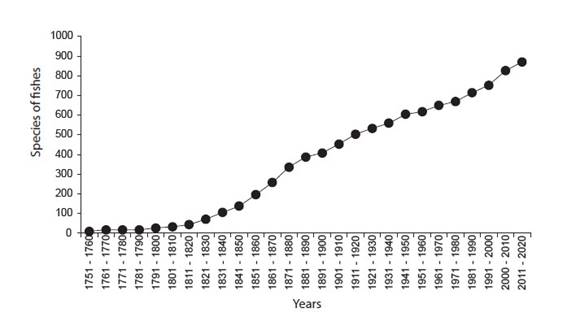

Taxonomic composition. - Of the total information analysed, 21527 batches deposited in 10 scientific collections were registered. This annotated checklist reveals that the ichthyofauna in Loreto is composed of 873 valid species (Appendix 2), which included 38 new species described in the last eight years (Ortega et al. 2012) and taxonomic changes like transfers, synonyms, and distribution range extensions.

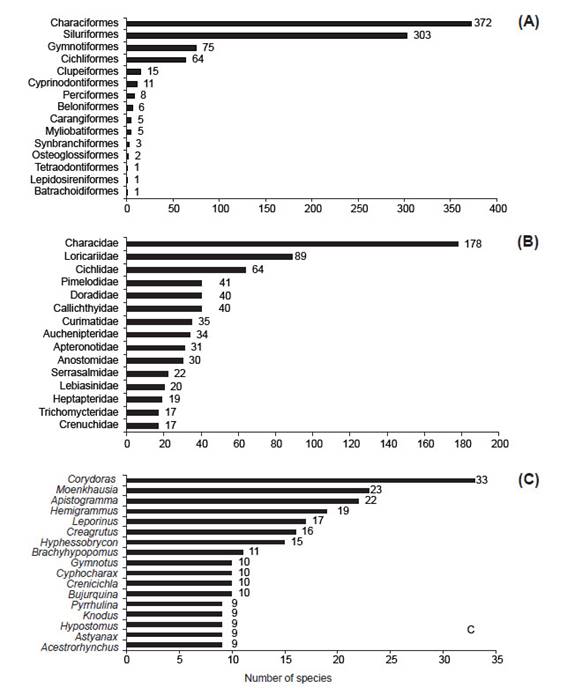

The species are distributed in 15 orders, 50 families and 331 genera (Table 2). Most of the ichthyofauna belongs to Otophysi (Cypriniformes, Characiformes, Silurformes, and Gymnotiformes) representing 86.0% (750 species), with Characiformes being the most diverse order (372, species, 42.6%), followed by Siluriformes (304, species, 34.8%), and Gymnotiformes (75, species, 8.6%); and with addition of Cichliformes (65, species, 7.4%). The remaining 11 orders were represented by 57 species (6.5%) (Fig. 3A).

Table 2 Number of family, genera, and species for each order of fishes registered in Loreto.

In terms of family richness, Characidae is the richest with 178 species (20.4%) followed by Loricariidae with 89 species (10.2%), Cichlidae with 64 species (7.3%), Pimelodidae with 41 species (4.7%), Callichthyidae and Doradidae with 40 each (4.6%) (Fig. 3B).

The most species-rich genera are found in Characidae; among them are Creagrutus, Hemigrammus, Hyphessobrycon, Moenkhausia. Among Loricariidae Hypostomus with 9 species, also Corydoras concentrated the most species in Callichthyidae with 33 of 40 species. In the same way, Apistogramma and Crenicichla together sum half of Cichlidae with 31 of 66 species. In Gymnotiformes, Brachyhypopomus and Gymnotus are represented by 21 species combined (Fig. 3C).

New species records. - New registers were added compared to the last list due recent taxonomic revisions, as Copella nattereri (Steindachner 1876), Astyanax symmetricus Eigenmann 1908, Jupiaba anterior (Eigenmann 1908), Knodus septentrionalis Géry 1972, Moenkhausia intermedia Eigenmann 1908, Trachelyopterus porosus (Eigenmann & Eigenmann 1888), Tridensimilis brevis (Eigenmann & Eigenmann 1889), Hypoptopoma brevirostratum Aquino & Schaefer 2010.

Others registers omitted in the last lists were added as, Pellona altamazonica Cope 1872, Pyrrhulina melanostomus (Cope 1870), Mylossoma albiscopum (Cope 1872), Knodus borki Zarske 2008, Spinipterus acsi Akama & Ferraris 2011, Aphanotorulus phrixosoma (Fowler 1940), Limatulichthys petleyi (Fowler 1940), Moema hellneri Costa 2003, Moema schleseri Costa 2003, Apistogramma amoena (Cope 1872).

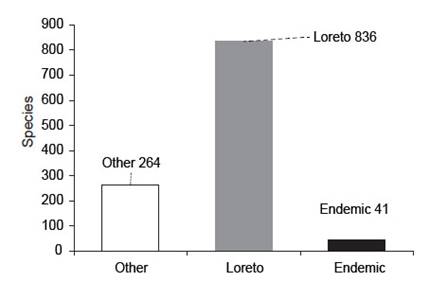

Species with restricted distribution. - A total of 41 species (4.7%) has restricted distribution for Loreto. Most of them are cichlids, belonging to Apistogramma, followed by the rivulids: Moema and Anablepsoides (Fig. 4, Appendix 2).

Figure 4 Freshwater fish species in Peru. Species distributed in other departments (white); species distributed in Loreto (gray) and species endemic from Loreto (black).

Commercially important species. - Large species that can surpass 1 m of standard length (SL), includes Arapaimidae, Osteoglossidae and mainly Pimelodidae (Brachyplatystoma, Pseudoplatystoma, Zungaro) which are known as migratory species. Some medium body-size species up to 30 cm belongs to Anostomidae (Leporinus, Megaleporinus), Auchenipteridae (Auchenipterus, Tetranematichthys), Bryconidae (Brycon, Salminus), Curimatidae (Potamorhina), Cynodontidae (Hydrolycus, Rhaphiodon), Loricariidae (Panaque, Pterygoplichthys), etc. Most of the communities harbor small species; that is, individuals with SL up to 10 cm, represented by 366 species (41%). Those species belong to Characidae (Bryconamericus, Moenkhausia), Iguanodectidae (Bryconops), Heptapteridae (Mastiglanis), Loricariidae (Aphanotorulus), Gymnotidae (Gymnotus), etc. Also, species up to 26 mm SL known as miniature species are present in this list, represented in Engraulidae (Amazonsprattus scintilla), Characidae (Axelrodia stigmatias, Priocharax pygmaeus, Tyttobrycon hamatus, Xenurobrycon heterodon), Crenuchidae (Odontocharacidium aphanes), Callichthyidae (Corydoras pygmaeus), Doradidae (Physopyxis ananas), Pseudopimelodidae (Microglanis zonatus), Trichomycteridae (Tridentopsis pearsoni), etc.

In terms of commercial importance, small and medium species are used for aquarists (Apistogramma, Corydoras, Hemigrammus, etc.); medium and large-sized species are for human consumption (Pseudoplatystoma, Prochilodus, Potamorrhina, etc.) (Appendix 2).

Non-native species. - Exotic species are reported. Coptodon rendalli and Oreochromis niloticus (Tilapia), the livebearers Poecilia and Gambusia affinis and Trichopodus trichopterus are represented in collections (Table 3).

Table 3 Non-native species introduced in Loreto.

Threatened species. - Currently, a total of 217 species (24.9%) are categorized following the IUCN criteria (Appendix 2). Only six species (0.7%) are considered threatened species (“Critical Endangered” (CR), “Endangered” (EN) and “Vulnerable” (VU)). Additionally, two species were considered “Near Threatened” (NT) and 36 species as “Data Deficient” (DD). Finally, 173 species are considered as “Least Concern” (LC).

Discussion

Taxonomic composition. - The diversity of fishes in Loreto is high, corresponding to 76.4% (873 spp.) of species known to occur in Peru (1141 spp.; MINAM 2019). Fifteen years ago, there were 597 recorded species (CONAM 2005), and in the last checklist 724 species were reported. This represents an increase of 20%. This value is incredibly high; over 76.4% of the species are recorded for only 28.7% (368.851 km²) of the Peruvian territory (1 285 000 km²). Compared to terrestrial vertebrates (Pitman et al 2013), fishes of Loreto have the highest percentage of IUCN species (25.1% vs. 19% or less) and the highest percentage of the total species reported for Peru (76.4% vs. 49.2% or less). Furthermore, fishes of Loreto have the second highest number of endemics species (4.9%) following amphibia (5.6%). This clearly shows the relevance of fish diversity in this region.

As in other lists or inventories in the Neotropical region, the most species-rich orders belong to Otophysi representing around 80% of species in total. In the same way, the most species-rich families follow the typical pattern for Amazonia fish composition: dominated for Characidae, Loricariidae, Cichlidae, Pimelodidae, Doradidae and Callichthyidae (Beltrão et al. 2019, Dagosta & de Pinna 2019).

New species records. - Although the list provided here considers species-level names only, there were some genera that could represent new species (Scorpiodoras, Phenacorhamdia, Astroblepus), even some of them are in the description process. Also, the species Rhamdia cf. quelen and Trichomycterus cf. rivulatus present some doubts related with its taxonomic status and need to be reviewed in detail. Besides that, Astroblepus, Chaetostoma and Trichomycterus are genera with typical distribution along an elevational gradient in the Andes, collected in the lowest slopes of Andes belonging to Loreto. Overall, those genera are diverse and endemic for sub basins; they can represent potential new species.

The Field Museum Rapid Biological Inventories have contributed to the knowledge of fishes from Loreto due to most of them being carried out in places with difficult access (Table 1). A total of 45 potential new species is estimated from 15 inventories in Loreto. Of these, only 11% have been described (Panaque schaeferi, Hypostomus fonchii, Corydoras ortegai, Hemibrycon divisoriensis, Mastiglanis yaguas and Cetopsorhamdia hidalgoi). This demonstrates there still is more effort to make in taxonomic and systematic studies.

Species with restricted distribution. - Four point seven percent of the species (4.7%, 41 spp. of 873 spp.) have restricted distribution in Loreto (Appendix 2). Most available information of fish endemicity is expressed by basin, for instance, Marañón and Ucayali basins have high levels of endemism with 25% and 16% respectively (Dagosta & de Pinna 2019). For this reason, our results are not comparable with previous studies because they are regional. However, we believe that the lower portion of each basin can contribute to the richness of Piedmont species which are different from lowland species.

Commercially important species. - Fishing is one of the main economic activities in Peruvian Amazon; 79 species are part of fisheries resources (García-Dávila et al. 2018), representing 9% of the total species from Loreto. Thus, most species are not used for fisheries or any commercial purposes (91%). As was mentioned before, there is an enormous diversity of fishes in terms of size, body shape, colour pattern, etc., which are of interest of researchers with different focuses (systematic, taxonomy, ecology, genetic, phylogeny, etc.). However, the Peruvian government considers all freshwater fishes as fisheries or hydro-biological resources, which are under the supervision of the Ministry of Production, rather than being considered as fauna under the management of the Ministry of the Environment. This misconception of fisheries resources is problematic for research (i.e.: permission for collecting fishes, permission for exportation, of individuals as well DNA analysis) and conservation (IUCN categorization). Several countries in the Neotropical region manage freshwater fishes as fauna that allow them to make research about checklists by basin or departments, conservation status and red list (IUCN), scientific expeditions, etc. This kind of management politics can improve the knowledge and conservation of freshwater fish diversity in Peru.

Finally, the present study can contribute to the management of fisheries to get precise catchment for species as well as for fauna since it contains an update of the fish list for Loreto.

Non-native species. - Exotic fishes have been introduced into natural habitats in Peru for different purposes since 1930s. For example, the tilapia (Coptodon rendalli) was introduced repeatedly into coastal and central Amazon basin to increase food availability to local community. Livebearers (Poecilia latipinna and Gambusia affinis) were introduced to control malaria insects during the 1950s (Ortega et al. 2007). Additionally, other introductions, such as Cyprinus carpio, Oreochromis niloticus and Poecilia reticulata also were registered for lower Huallaga River (Ortega et al. 2007).

Trichopodus trichopterus can be found around Iquitos streams and recently was collected next to Quistocoha by H. Sánchez (Pers. Comm. 2019). Many decades ago (1980-1990), there was some ornamental activity around this group from Moronacocha, a lagoon very close to the city and connected to Nanay River. In addition, Danio rerio (Cypriniformes) known as zebra fish, were registered in a consulting work in a lentic body of water between Nauta and Iquitos (Urku & Brirell 2016). The introduction of exotic species into natural habitats caused several problems such as predation, competition for resources and for niches. The species reported herein are adapted to warm water, and that facilitated their dispersion (Ortega et al. 2012, Ortega et al. 2007). Some of these species do not have vouchers in collections but as mentioned before, they are already in natural habitats (Table 3) and it is necessary to take some control actions to minimize the effects.

Incidental presence of shark has been recorded in Iquitos. Carcharhinus leucas was registered the first time in 1952 by Myers who identified a single specimen by a photo (Gausmann 2018, unpublished report). Although the bull shark has been registered in several rivers in different continents, the farthest penetration and longest movement into freshwater is provided for the Amazon River, more than 5000 km away from the mouth of the river at the coastline of the Atlantic Ocean. The distribution of this species is limited by water temperature, not only in coastal, but even in freshwater systems (Castro 2010).

Gaps of information. - Even though, almost all the sub-basins of the department have been studied, there still are some gaps to fill. For instance, the middle Napo River, some tributaries of Marañón River, Yavarí River, and some tributaries between Huallaga River and Ucayali River (Fig. 1). These areas should be prioritized for ichthyological surveys.

Conservation. - Several threats have been identified in Loreto derived from economic activities such as deforestation, illegal logging, artisanal fluvial gold mining, pollution, road constructions, hydroelectric dam and Hidrovia projects. All of these threats have affected the environment in the past but might especially affect aquatic habitats and their fish fauna in the future.

Although the time for the collections were limited, the information obtained in biological inventories was valuable. Not only to know the diversity in those places at the time, but also to know the conservation state of the area and the local communities that live there. It is important to mention that the most remarkable thing of those inventories was that they were taken as a baseline to propose national protected areas (NPA) where 53% of them led to the creation of an NPA in some category (Pitman et al. 2021) (Table 1).

It is worth mentioning that the last meeting of categorization of Peruvian fishes was focused on Andean fishes (IUCN, 2014). “Near threatened” and “Data deficient” indicate lack of information about distribution, natural history, size or density population and ecology of those species (Bertaco et al. 2016), hence encouraging more studies to be made on those species. Besides that, species considered as “Least concern” can give an appearance of the stability of the conservation status of those species; however, they need to be updated due new threats, which can appear. Overall, more efforts need to be made to complete the assessment of Peruvian fish species and particularly from the Loreto department.

uBio

uBio