INTRODUCTION

With 189 species of bats (Pacheco et al. 2021), Peru has the third-highest bat species diversity after Indonesia and Colombia (217 species, Ramírez et al. 2021). The Yungas, especially mid to upper elevation on the east slope of the Andes, are high-endemism areas for several taxa, such as mammals and bats (Pacheco 2002, Pacheco et al. 2007a). Therefore, it is not unexpected that in Peru, out of the nine endemic species of bats (Pacheco et al. 2021), three (Mormopterus phrudus, Eumops chiribaya, and Anoura javieri) occur above 2000 m a.s.l., in a restricted range in one or two departments. Bat faunal inventories for montane forest sites provide important comparative information for understanding bat community structure. However, only five montane forests - Vilcabamba (Emmons et al. 2001, Solari et al. 2001), Manu (Pacheco et al. 1993), Yanachaga (Vivar 2006), and Pampa Hermosa (Refulio 2015), and Carpish (Pacheco & Noblecilla 2019) - have been sampled at altitudes including 2000 m and above, comparable to those of Río Abiseo National Park. Along the montane forest of the eastern slopes of the Andes in Peru, the forest limit exhibits considerable variation. Generally, the Andes are lower further north in the Cordillera Blanca and connect at lower altitudes with the Ecuadorian Andes in the Huancabamba depression zone (Hoffstetter 1986). Bat species diversity and abundance decline with altitude, a phenomenon analyzed and discussed by Graham (1983, 1990) and Patterson et al. (1996). Both authors noticed a wider altitudinal range in highland bats compared to birds. Likewise, Graham (1983) suggested that bat speciation probably occurred in the lowlands, whereas cloud forest populations have had less opportunity for allopatric speciation. Also, ecological and physiological factors such as temperature reduction, resource abundance, and habitat complexity may have prevented successful emigration to the highlands. Regarding the bat fauna of Río Abiseo National Park, a complete bat inventory has not been published yet. Here, we present the species list for bats found above 2000 m a.s.l. in the western zone of Río Abiseo National Park, headwaters of the Montecristo River, and the eastern slope of the Andes, which was a primarily undisturbed area at the time surveys were undertaken and still nowadays.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

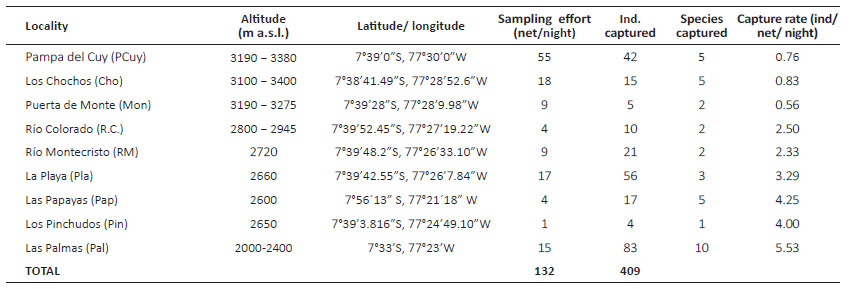

We evaluated nine localities: Pampa del Cuy, Los Chochos, Puerta de Monte, Rio Colorado, Rio Montecristo, La Playa, Las Papayas, Los Pinchudos, and Las Palmas which are located on the south side of the Montecristo River sub-basin in the Huicungo District, Mariscal Cáceres Province, San Martín Department, Peru (Table 1). The Montecristo River reaches the Abiseo River part of the Huallaga basin. All of them are located between 2000 and 3380 m a.s.l., corresponding to the Holdridge zones of pluvial montane tropical forest (bp-MT) around 2500-3800 m a.s.l. and pluvial lower montane tropical montane forest (bp-MBT) around 2300 - 2600 m a.s.l. Rains are abundant and range between 1000-4000 mm per year. Between June and August, the possibility of days without rain increases; in these months, the nights can be clear and therefore colder, often reaching the freezing point in the grasslands, with the formation of frost (Young & Leon 1988, 1990). Young and Leon (1988) briefly describe these localities and their vegetation as follows:

Pampa del Cuy (3190-3380 m a.s.l.) and Los Chochos (3100-3400 m a.s.l.). These U-shaped glacial valleys are characterized by grasslands with occasional patches of elfin forest along their side slopes. They are close to the continuous forest that begins at elevations below 3200 m. The grasslands predominantly consist of species from the genera Calamagostris, Cortaderla, Festuca, and Stipa, but in some parts, they are mixed with some shrubs, such as Loricaria sp., a common species. Trees from various genera, such as Brunellia, Escallonia, Gynoxys, Hedyosmun, Hespermeles, Miconia, and Weinmannia occur in the patches of elfin forest.

Puerta de Monte (3190-3275 m a.s.l.). The sampled area is contiguous to Pampa del Cuy and serves as a transition area to the “entrance” to the continuous forest. The bamboo genus Chusquea is dominant in some parts of this locality as well as many shrubs. Trees in this area reach heights from 5 to 15 m and they may be covered by mosses, lichens, and ferns.

Río Colorado (2800-2945 m a.s.l.), Río Montecristo (2720 m a.s.l.), La Playa (2660 m a.s.l.), Las Papayas (2600 m a.s.l.), Los Pinchudos (2650 m a.s.l.) and Las Palmas (2000-2400 m a.s.l.). These localities are part of the very humid montane forest. The understory of the continuous montane forest is composed of small trees and shrubs, bamboos (Chusquea scandens and four other species), and tree ferns (Cyathea and Sphaeropteris atahuallpa). Other plants that make up the understory include herbaceous, climbing orchids of Pleurothallis and Stelis genera. Trees reach 20-25 m tall. The locality Las Palmas is a much richer forest with a high diversity of tree genera, such as Cecropia, Clusia, Ficus, Nectandra, and Solanum, and shrubs such as Piper.

Sampling was done over four expeditions by Mónica Romo, Mariella Leo, and Abigail Bravo during July and August 1987, July 1988, August 1989, and July and August 1990. Mistnets of 6, 12, and 20 m wide were set, making a total sampling effort of 132 nets/night and 409 individuals captured. Only 250 of the captured bats were collected, the uncollected bats being mostly those of common species already well represented. The sampling effort for each locality is shown in Table 1. The nets/night go from 1 net/night in Los Pinchudos to 55 nets/night at Pampa del Cuy, the most sampled locality. The capture rate refers to the number of individuals divided by nets/night in each locality and is referred as ind/net/night. At each locality, mist nets were placed inside the forest and at the forest edge, along transverse and longitudinal lines (in Pampa del Cuy and Los Chochos), near lagoons, or across streams or rivers (in Pampa del Cuy, Puerta de Monte, Río Colorado, Río Montecristo, and Las Palmas). Open nets were sometimes more evident because of the excessive humidity or the moonlight. Nets were left open from 18:00 to 22:00 h. Some specimens were captured directly from daytime roosts (near Las Papayas and in Los Pinchudos cave).

Specimens were collected and then preserved following the methodology proposed by Nargorsen and Peterson (1980). Most individuals collected were identified in the field using keys for identification, such as Pine (1972), Handley (1984), Davis (1980), Shump and Shump (1982), and LaVal (1973). Additionally, we compared side by side our specimens with those housed in the Museo de Historia Natural of the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. Individuals from Micronycteris were identified by comparison with specimens housed in the U.S. National Museum of Natural History (USNM, Washington). It is important to acknowledge that subsequent systematic studies have utilized several specimens, resulting in changes to the names initially attributed to them when the research was conducted, consequently, the nomenclature of these species has been revised and updated. This was exemplified in the cases of Anoura aequatoris (Pacheco et al. 2018) and A. fistulata (Mantilla-Meluk et al. 2014). Study skins were prepared, and additional specimens were initially fixed in a 10% formaldehyde solution, which was later replaced with 70° alcohol. All specimens are deposited at MUSM and in Appendix 1 are listed the respective catalog numbers, localities, and sex. We follow the taxonomic nomenclature used in Mantilla-Meluk et al. (2014) and Pacheco et al. (2018, 2021).

RESULTS

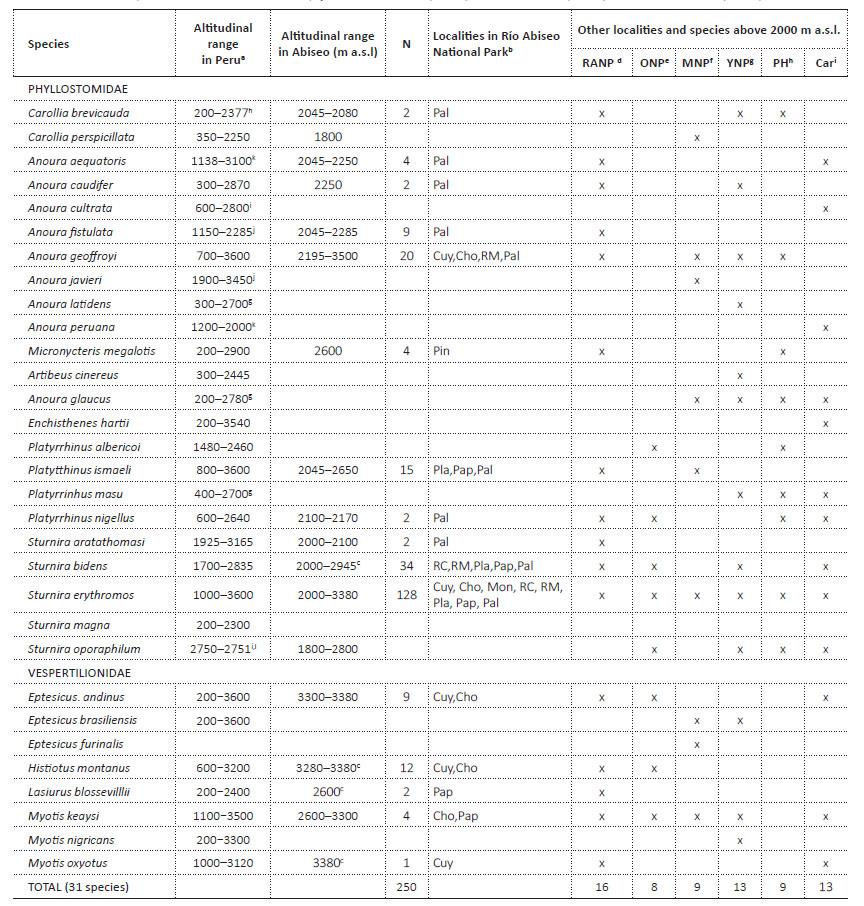

We collected 250 specimens belonging to 16 species of the Phyllostomidae (12 species) and Vespertilionidae (four species) families (Table 2). Four species (Sturnira bidens, Histiotus montanus, Lasiurus blossevillii, and Myotis oxyotus) exceeded the altitudinal range previously recorded for Peru, while one (Sturnira aratathomasi) is the third record of this species for the country (see McCarthy et al. 1991, Pacheco & Hocking 2006).

Table 2 Bats recorded between 2000 and 3500 m a.s.l. in Río Abiseo National Park and other localities in Peru. Superscript: a= Graham (1983), Koopman (1978), McCarthy et al. (1991), Patterson et al. (1996), Solari et al. (2001), Pacheco and Hocking (2006), Medina et al. (2012) or other authors mentioned below. b=localities abbreviations: Cuy-Pampa del Cuy, Cho-Los Chochos, Mon-Puerta de Monte, RC-Río Colorado, RM-Río Montecristo, Pla-La Playa, Pap-Las Papayas, Pin-Los Pinchudos, Pal-Las Palmas. c= extension of altitudinal range. Abbreviations of localities with bats above 2000m and reference d= RANP Río Abiseo National Park (this work). e= ONP Otishi National Park 2050-3350 m a.s.l. (Emmons et al. 2001). f= MNP Manu National Park 2000-3350 m a.s.l. (Pacheco et al. 1993). g= YNP Yanachanga Chemillen Nationla Park 2050-2780 m a.s.l. (Vivar 2006). h= Pampa Hermosa 2333-2900 m a.s.l. (Refulio 2015). i= Carpish 2400-3000 m a.s.l. (Pacheco & Noblecilla 2019). j= Pacheco et al. (2018). k= Arias et al. (2016). l= Pacheco et al. (2007).

As expected, fewer bats were collected (0.76, 0.83, and 0.56 individuals/net/night) in the localities where grasslands occur (Pampa del Cuy, Los Chochos, and Puerta de Monte) upper 3190 m a.s.l. than in the forested localities below 2945 m a.s.l., and more and more bats as the altitude was lower. (2.50, 2.33, 3.29, 4.25, 4, and 5.53 ind/net/night) (Table 1). The nets in Colorado (2800 - 2945 m a.s.l.) and Montecristo rivers (2720 m a.s.l.) had a capture rate of 2.33 to 2.55 ind/night /net, and the forest sites (2000-2650 m a.s.l.) had a capture rate of 3.29 to 5.53 ind/night/net. The locality with more specimens (83) and species (10) captured was the lowest altitude locality of Las Palmas (2000-2400 m a.s.l.). Following are some notes related to altitude distributions and extension of the altitudinal range of noteworthy records:

Sturnira aratathomasi Peterson and Tamsitt, 1968. This is one of the few specimens for Peru as it has only been collected in two other localities: one individual in La Peca, Department of Amazonas, at 3165 m a.s.l. (McCarthy et al. 1991) and three in Cconoc, Department of Apurimac (Pacheco & Hocking 2006).

Sturnira bidens (Thomas, 1915). This record in Abiseo slightly extends the altitudinal range for Peru to 2945 m a.s.l., compared to the altitudes mentioned before (Graham 1983: 1700-2800 m a.s.l. Patterson et al. 1996: 1990 - 2835 m a.s.l.).

Histiotus montanus Philippi and Landbeck, 1861. This species had been recorded in Peru, up to 3220 m a.s.l. (Patterson et al. 1996), but in Abiseo it has been collected up to 3280 m a.s.l.

Lasiurus blossevillii (Lesson & Garnet, 1826). This species was found in a diurnal roost, a bush in a ravine area at 2600 m a.s.l. This is apparently, the first record of a diurnal roost for this species in South America.

Myotis oxyotus (Peters, 1867). Only one individual was collected at 3380 m a.s.l., which is above the previously known altitudinal range in Peru between 1050-3120 m a.s.l. (Patterson et al. 1996).

DISCUSSION

This list of species from high altitudes above 2000 m records some species that have expanded in altitude, but mainly reflects the need for more specimen collections, especially of rare or difficult-to-collect species, such as S. aratathomasi that were only collected in two other localities in Peru: one individual in La Peca, Amazonas Department, at 3165 m a.s.l. (McCarthy et al. 1991) and three in Cconoc, Department of Apurimac (Pacheco & Hocking 2006). Also, three of the four altitudinal range expansion records for Peru correspond to species of Vespertilionidae.

The importance of these collections for enhancing the knowledge of the biodiversity and systematics of species is evident. For example, when Platyrrhinus specimens were collected in Abiseo between 1987 and 1990, P. dorsalis was considered a species complex (Carter & Rock 1973) but later studies using specimens from various localities helped clarify its taxonomic status (Velazco and Solari 2023, Velazco 2005).

Comparable localities in Peru, such as the Yanachaga (Vivar 2006), Carpish (Pacheco & Noblecilla (2019), Otishi (Emmons et al. 2001), Pampa Hermosa (Refulio 2015) and Manu (Pacheco et al. 1993), have registered thirteen, thirteen, eight nine, and nine species, respectively, compared to sixteen species in Río Abiseo. The cumulative tally of species across these localities is 31 but considering additional localities above 2000 m (Graham 1983; Koopman 1978, McCarthy et al. 1991, Patterson et al. 1996, Solari et al. 2001, Pacheco & Hocking 2006, Medina et al. 2012, Bernabé 2019), it is plausible that the actual count of bat species thriving above this altitude could potentially extend to 34. One of the causes of the difference in number among localities might be due to different collecting efforts. Additional localities should be surveyed better to understand the Peruvian bat diversity inhabiting above 2000 m. Leveraging recent advancements in acoustic methodologies could significantly enhance our capacity to amass a comprehensive understanding of bats.

Considering altitudinal climatic variation, forest boundaries along the Andes vary slightly and, consequently, the altitudinal limits of bat species may differ along the Andes. For example, forest boundaries and U-shaped valleys in Abiseo and northern Peru occur at lower elevations than the same formations in southern Peru (Young & León 1991). However, this fauna faces intense human pressure from colonization, leading to accelerated deforestation and severe erosion (Young & Valencia 1992). Additional studies of bats in the Andes would help understand the interaction of high environmental variability and human disturbance on a bat community structure and distribution.

uBio

uBio