Introduction

Beak deformity is a rare feature and has a low frequency, with 0.5% of cases in wild bird populations (Pomeroy 1962). Possible causes for the beak abnormality can be genetic, developmental, injury or disease (Craves 1994). The most common cause of beak anomaly may be overgrowth of the dermotheca and rhamphotheca; however, the bone structure remains normal (Taylor & Anderson 1972, Thompson & Terkanian 1991).

Deformed beaks vary from small to extreme proportions (Gorosito et al. 2016) and can assume different shapes, such as: crossed mandibles, decurved upper mandible, upcurved lower mandible, elongation of both mandibles, bent to the side and gapped (BTO 2024). Deformed beaks can affect the health of birds (Van Hemert et al. 2012), but some individuals adapt to obtain food (Souza et al. 2016, Purificação 2019). The alignment of the feathers with the use of the beak -i.e., preening, keeps the plumage in good condition and removes dirt particles and ectoparasites, such as feather lice and ticks (Scott 2010). Birds with beak deformity can also have normal feathers and health status (Souza et al. 2016, Santos et al. 2018).

Beak deformities in wild birds are relatively rare in nature, and cases are also rarely reported in the Brazilian scientific literature (Vasconcelos & Rodrigues 2006, Souza et al. 2016, Purificação 2019, Smith et al. 2019, Moura et al. 2019, Moura et al. 2020, Moura et al. 2022, Moura et al. 2023). These published records of beak deformities are timely and provide us with information that can tell us something about the health conditions of bird populations.

Description of records

We report here three cases of deformities in beaks of wild birds in the southwestern Brazilian Amazon:

Dendrocincla merula (Lichtenstein, 1820)

White-chinned Woodcreeper - (Passeriformes: Dendrocolaptidae)

A specimen of White-chinned Woodcreeper with a deformity in the beak was captured with a mist net on October 6, 2020 in an area covered by dense terra-firme forest, in the municipality of Pauini, Amazonas (08°30'37.6” S, 69 °7'22.9” W). The bird had a shorter maxilla in relation to the mandible (Fig. 1A). The mandible lacked a tip and a side part on both sides. On the right side, it was also possible to observe a small fissure (Fig. 1B). After obtaining the biometric data, the bird was released close to the capture site and flew normally. We were unable to record the specimen feeding, but it appeared to be healthy at the time of capture.

Figure 1 White-chinned Woodcreeper, Dendrocincla merula, with beak deformity. A: Short maxilla lacking the distal region and part of the lateral margin on both sides; B: cleft on the right side of the maxilla. Photos: Luana Alencar.

Amazona ochrocephala Gmelin, 1788

Yellow-crowned Parrot - (Psittaciformes: Psittacidae)

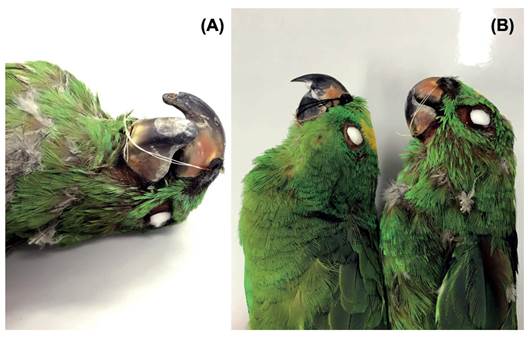

On December 24, 2018, a Yellow-crowned Parrot, which died at the Wild Animal Screening Center of the Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (CETAS/IBAMA-AC), was donated to the Ornithology Laboratory of the Federal University of Acre (UFAC), in Rio Branco, and prepared for the taxidermy technique. The adult individual (♂ testicles: 2 × 3 mm; Collection number: AC-1168), presented a profound deformity in the maxilla (Fig. 2A). The maxilla wascrossed, facing to the right, not over the mandible as in a normal specimen (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2 A Yellow-crowned Parrot, Amazona ochrocephala, with crossed jaw. A: beak detail; B: Comparison of the cross-beaked specimen with a normal-beaked specimen. Specimens belonging to the ornithological collection of the Federal University of Acre (Example without beak deformity: AC -1205; specimen with beak deformity: AC-1168). Photos: Ednaira Santos.

Pheugopedius genibarbis (Swainson, 1838)

Moustached Wren - (Passeriformes: Troglodytidae)

On August 7, 2012, we captured an individual of Moustached Wren in the Zoobotanical Park of the Federal University of Acre (09°50'07.2" S, 67°52'12.3" W), in the municipality of Rio Branco, Acre. This one died, possibly due to stress during capture. During individual's removal from the net, we noticed accentuated curvature in the maxilla and mandible (Fig. 3). In addition, the mandible in this individual was slightly larger than the maxilla (Fig. 3). After scientific taxidermy, it was verified that it was an adult female (♀ ovary: 3 × 2 mm) that was incorporated into the scientific collection under the Collection number: AC-443.

Figure 3 Moustached Wren, Pheugopedius genibarbis, with beak deformity compared to a normal beak specimen (right). Note the curvature of the maxilla and the longer mandible of the specimen on the left. Specimens belonging to the ornithological collection of the Federal University of Acre (Example with beak deformity: AC-443; specimen without beak deformity: AC-223). Photo: Edson Guilherme.

We present in Table 1 the beak measurements of the specimens reported here in comparison with the average beak measurements of specimens without deformation (for each species) deposited in the ornithological collection of the Federal University of Acre, Brazil.

Table 1 Beak measurements of three species of wild birds with deformity (present study) and without deformity (specimens housed in the scientific collection) from the southwest of the Brazilian Amazon. SD = standard deviation; (n) = number of specimens measured; max.-min.= maximum and minimum values found.

| Maxilla (mm) | Mandible (mm) | Base width of beak (mm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Present study | Mean±SD (n) max.-min. | Present study | Mean±SD (n) max.-min. | Present study | Mean±SD (n) max.-min. |

| Dendrocincla merula | 27.8 | 26.8±1.1 (6) 28.4-25.1 | * | 17.1±1.4 (6) 19.9-16 | 8.2 | 8.2±0.4 (6) 8.9-7.7 |

| Amazona ochrocephala | 29.8 | 31.8±1.8 (11) 34.5-28 | 21.8 | 20.6±2.1 (11) 25.6-18.6 | 18.3 | 18.8±1.1 (11) 21-17,4 |

| Pheugopedius genibarbis | 15.8 | 16.1±1.2 (8) 17.6-13.8 | 11.9 | 12.5±2.9 (8) 14.8-10.2 | 6 | 5.4±0.3 (8) 6.1-5 |

* The bird was released before this measure was taken

Finding answers to the causes of beak deformities is not simple (Craves 1994), since these anomalies are related to several factors such as wear or trauma (Pomeroy 1962), nutritional deficiencies (Stevens et al. 1984), viral, bacterial, fungal and/or parasitic infections (Gartrell et al. 2003, Gorosito et al. 2016, Zylberberg et al. 2016). Generally, birds with these beak deformities die prematurely (Sogge & Paxton 2000) and this may contribute to the scarcity of information on this topic (Barreiro et al. 2002).

Birds of the Dendrocolaptidae family are abundant in neotropical forests, mainly in primary forests (Sick 1997). In a bibliographic survey, a record of beak deformity was found in Dendrocincla fuliginosa (Verea et al. 2012), but during searches on the collaborative website Wikiaves (www.wikiaves.com.br), we did not find records of beak deformity in Dendrocincla merula. Dendrocolaptids use their beak intensively in the search for insects and small vertebrates, where they explore in crevices in wood, rip splinters from tree bark and remove moss with lateral blows (Sick 1997). In the case presented here, this behaviour may have been the cause of this individual's maxillary tip breaking. By continuing to forage with a broken maxillary tip, probably the lateral margin also broke, resulting in the cleft observed on the right side. Although specimens of this family have fragile beaks, the record of beak deformity in the Dendrocolaptidae family has been quite uncommon.

In Brazilian territory, few parrot species were recorded with beak deformity (Souza et al. 2016). In the case presented here, everything indicates that the pampas parrot donated from CETAS/IBAMA was a captive animal. He was excessively thin (weight: 493.7 g) and probably his diet was low in vitamins and calcium (see Tangredi 2007). The deficiency of these minerals, even when the animal was a chick, may have contributed to the deformity of the maxilla. The disproportionate growth at the tip of the maxilla must have been due to the fact that the animal could not use the tip of the beak to break more rigid food.

According to Wilkinson (1953) temporary beak deformities are common in cage birds and attribute this anomaly to incorrect feeding, however, with the bird's maturity, the deformed beak region falls off and growth occurs normally. In this case, the specimen of Amazona ochrocephala presents the structure of the resistant beak and the crossed maxilla over the mandible is characteristic observed in permanent anomalies (Pomeroy 1962).

The Moustached Wren (P. genibarbis) captured and collected in the Zoobotanical Park (PZ) of the Federal University of Acre, presented an unusual curvature in the maxilla, a detail not observed in other individuals of this species deposited in the scientific collection of the Laboratory of Ornithology at UFAC. The PZ is a fragment isolated by urban matrix and presents an overpopulation of some bird species, including P. genibarbis (Pedroza & Guilherme 2021). Some individuals in this population who are isolated by urban matrix have presented a neoplastic disease called eyelid papilloma (Souza et al. 2017). Populations isolated from each other are more likely to have diseases and anomalies, which may be the case for the individual in this study. Cases of beak deformities in species of the Troglodytidae family are rare. Sick (1997) reports that when capturing a Musician Wren (Cyphorhinus arada) he observed the beak turned slightly to the side. In our review of the literature, we did not find other cases of beak deformities in specimens of this family.

There are still occasional reports of beak anomalies in wild birds (Pomeroy 1962, Craves 1994, Handel et al. 2010, Gorosito et al. 2016, Smith et al. 2019, Souza et al. 2016, Purificação 2019, Smith et al. 2019, Moura et al. 2020, Moura et al. 2022, Moura et al. 2023). Knowledge about these cases will grow as researchers around the world begin to realize the importance of publicizing them. It may happen that a researcher is faced with a bird with a deformity in the beak but neglects the case. Only with more reports can we better understand the occurrence and causes of these beak deformities in wild birds.

uBio

uBio