Introduction

The advent of Internet popularization provided several changes in conceiving communication between people (Copetti & Quiroga, 2018; Matias & Matos, 2013). In recent years, the growth in Internet access in Brazil has demonstrated its relevance as a facilitator of relationships, communication, and as a tool for solving everyday tasks (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE), 2019; Seabra et al., 2017).

In this context, one of the leading exponents of online communication is the social networking sites that favor sharing various elements between people, such as contacts and information (Patrício & Gonçalves, 2010; Rosado et al., 2014). According to the Brazilian Internet Steering Committee (2019), one of the main online activities in Brazil is sending instant messages via WhatsApp, for example. From a social perspective on virtual social networks, it is possible to reflect the accessibility and reach of such communication. Individuals of different ages, social classes, and cultures can participate in this environment (Macedo, 2016; Krug et al., 2018).

Virtual social networks give individuals the possibility to create an online profile in which they can present themselves virtually, create connections with other individuals connected in the network, and thus enter even more in the navigation of these associations (Boyd & Ellison, 2007; Celli et al., 2014; Uski & Lampinen, 2016). Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram are some examples, with millions of users considering them services that aim to interact with people (Kumar & Geethakumari, 2014; Lee et al., 2015; Recuero, 2012).

Personality traits (Durak & Senol-Durak, 2014; Puerta-Cortés & Carbonell, 2014; Wang et al., 2015), addictions (D’Arienzo et al., 2019), and romantic relationships (Flach & Deslandes, 2017; Haack & Falcke, 2017; Hobbs et al., 2017) are examples of investigative aspects considered by researchers concerning life on the Internet. In this way, individuals prefer specific contents that best meet their needs or motivations (Wang et al., 2015).

Individual characteristics, among which personality traits highlight (Puerta-Cortés & Carbonell, 2014), are present when selecting the media of interest. Personality is important to predict Internet use and is associated with global use (Mark & Ganzach, 2014) or problematic use (Durak & Senol-Durak, 2014). The complex use of the Internet, which damages the individual’s personal and professional life, has an association with neuroticism (positive) and conscientiousness (negative) (Durak & Senol-Durak, 2014). Studies indicate that neuroticism is related to Internet dependency (Blackwell et al., 2017; Bowden-Green et al., 2021) and addiction (Matos et al., 2016; Samarein et al., 2013). However, sociability and extroversion are negatively associated with maladaptive behaviors (Servidio, 2014). Therefore, personality generally influences society’s online choices and behavior (Arnoux et al., 2017; Azucar et al., 2018; Kircaburun et al., 2020).

The Internet also brought about several changes in the origin and maintenance of relationships, creating new environments for virtual interactions and relationship networks, such as developing friendships and romantic relationships (Flach & Deslandes, 2017). Regarding the latter, Haack and Falcke (2017) describe those online services facilitate contact between partners. However, the success of a relationship depends on the person-to-person interaction, since it provides greater consistency, adding intimacy, commitment, passion, and satisfaction, thus reducing marital problems.

To evaluate the passive and active use of social networking sites (Wang et al., 2018), the problematic use of the Internet (Bothe et al., 2018; Pereira et al., 2020), and the use of social networking sites (Wang et al., 2015), psychometric scales and instruments were developed.

So far, the only scale aimed at evaluating the motivations for using social media is the Social Media Motivations Scale (SMM-S; Orchard et al., 2014), which was developed in the United Kingdom. It applies the Uses and Gratifications Theory (Katz et al., 1974) as a theoretical basis. This perspective describes that users choose their favorite online social networks based on personal goals and needs, which can be influenced by psychological and social aspects. Furthermore, the benefits and returns arising from using a particular online social network also affect this choice (Orchard et al., 2014). The SMM-S was structured with open questionnaires on the daily use of online social networks (quantity, time spent, preferred type), along with questions about the benefits of their service, and was measured using a Likert scale. Concerning the research methods, the number of items per dimension was generated using the principal component analysis (PCA), and the internal consistency of the factors was determined by Cronbach’s alpha.

In this way, to determine the main motivations for using online social networks is of paramount importance in the current setting since they are an important variable to understand the backgrounds and consequences of online behavior among the adult population. In this sense, the present study sought to adapt and raise evidence of the SMM-S (Orchard et al., 2014) in the Brazilian context. Additionally, this research aimed to a) understand the reasons for using social media on life satisfaction, and b) evaluate how personality traits, using the Big Five personality model (Hauck et al., 2012), are associated with the reasons for using online social networks.

Method

This study had a survey designed and was conducted in two stages. The first stage included the translation, adaptation, and evidence gathering of the internal structure, and attempted to replicate the British model based on confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) procedures. The second stage presented an alternative for the internal structure compared to the original model, using exploratory factor analysis (EFA) techniques (Hauck, 2019). In addition, the study presented the axiological network for the construct.

Stage 1 Participants

At the beginning of the research, 600 Brazilian adults joined the study. The inclusion criteria were being 18 years old or older and using at least one online social network. The sample consisted of individuals aged between 18 and 41 (M = 23.5; SD = 2.94), 73.5% of whom were women (n = 441). Regarding the marital status, most participants reported being single (85.8%; n = 515). They came from all Brazilian regions: 62.8% (n = 377) were from the Southeast, 14.3% (n = 86) from the South, 8.7% (n = 52) from the Center-West, 7.2% (n = 42) from the Northeast, and 5.3% (n = 32) from the North; .2% (n = 1) lived abroad; and 1.5% (n = 9) did not respond to this inquiry. Their average income was from 1 to 3 minimum wages (R$ 998.00 - R$ 2,994.00). Concerning their education level, 570 individuals reported having an undergraduate degree (92.2%), and having studied in public institutions (n = 368; 66.3%), private institutions (n = 138; 24.7%) or both (n = 25; 4.2%). One (1) person reported not having attended high school and 29 not having a college degree. Their favorite social networks were Instagram (23.2%; n = 142), Twitter (8.7%; n = 53), and Facebook (3.5%; n = 22).

Stage 2 Participants

Six hundred (600) Brazilian adults took part in this stage of the research. The inclusion criteria remained the same as those mentioned in stage 1. The sample consisted of individuals aged between 28 and 69 years (M = 39.46; SD = 9.5), 73.16% of whom were women (n = 439). Regarding the marital status, 356 reported being married or in a stable relationship (59.3%) and 206 being single (34.3%). The participants came from the five Brazilian regions: 57.2% (n = 343) were from the Southeast, 17.7% (n = 106) from the South, 11.8% (n = 71) from the Center-West, 6% (n = 36) from the North, and 5.5% from the Northeast (n = 33); .5% (n = 3) lived abroad; and 1.3% (n = 8) did not respond to this inquiry. Their average income was from 3 to 6 minimum wages (R$ 2,994.00 - R$ 5,988.00). Concerning their education level, only two (2) individuals did not attend high school, and 16 did not pursued undergraduate studies. The rest (n = 584) reported having an undergraduate degree or being currently in college, out of which 295 (49%) studied in public institutions, 216 (36 %) in private institutions and 73 (12%) in both. Their favorite social networks were Instagram (18.3%; n = 110), WhatsApp (9.5%; n = 57), and Facebook (7.5%; n = 45).

Instrument’s Adaptation Procedures

The SMM-S (Orchard et al., 2014) is an instrument that aims to assess the motivations for using online social media and consists of 40 items (for example: «Because it’s a good distraction from other things»). In its original version, it has ten (10) factors; namely, procrastination (α = .89), freedom of expression (α = .87), conformity (α = .80), information exchange (α = .81), new connections (α = .79), ritual (α = .80), social maintenance (α = .75), escapism (α = .82), recreation (α = .83), and experimentation (α = .59). In the process of adapting the instrument to the Brazilian Portuguese context, authorization was first requested from the authors of the original version of the SMM-S (Orchard et al., 2014). Once the permission was granted, the items were translated by two language specialists, and then reviewed by a team of translators in both languages (the authors of this article). Subsequently, to guarantee the semantic validity of the instrument, a pilot study was conducted with a non-probability sample of adult users of online social networks (at least ten) who answered the instrument considering a set of criteria (duration, response, understanding the adequacy of the items). After reviewing the structure of the items, the SMM-S was studied with a general population.

Instruments

The participants answered the online survey with a) A sociodemographic questionnaire (age, gender, marital status, education, income, region of Brazil, favorite online social network). b) The Portuguese version of the SMM-S adapted to the Brazilian context. c) The Satisfaction with Life Scale (Zanon et al., 2014), which assesses respondents’ current general satisfaction with life. It consists of five (5) questions (for example: «My life is close to my ideal»,) which were evaluated using a seven-point Likert scale (1 = I strongly disagree to 7 = I strongly agree). The measure has good internal consistency (α = .87), with its validity being examined through the CFA and invariance tests. d) The Reduced Personality Markers Scale (Hauck et al., 2012), which assesses the personality based on the Big Five personality model. It is made up of 25 items, which are answered with a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree. The scale is divided into five factors; namely, extroversion (α = .74), socialization (α = .80), conscientiousness (α = .76), neuroticism (α = .55), and openness to experience (α = .57), with each construct being measured by five items.

Data Collection Procedures

Data collection was conducted online, from July to August 2019, via Google Forms. The invitation to participate in the research was made in person, by e-mail, and through online social networks, considering the study inclusion criteria. It is noteworthy to mention that a downloadable version of the Free and Informed Consent Term was available at the first section of the Google Forms. The signature was associated with agreeing the question «Do you accept to take part in this research?» The average response time was 15 minutes.

Data Analysis

First, the database was inspected, and missing cases and discrepant responses were adequately treated. Then, sequentially, data were analyzed by CFA procedures using the Mplus software (Muthén & Muthén, 2012) to observe the adequacy of the internal structure compared to the British version. The analytical process was estimated using the weighted least squares mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV), recommended for ordinal data. The fit indices used to examine the adequacy of the models were: chisquare test, where the ratio between chi-square and degrees of freedom (x²/df) considered values below 5; comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), both of which considered values above .90; and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), which considered values below .08 (Brown, 2014; Marôco, 2010; Schweizer, 2010).

Due to the results of the CFA, an EFA was performed using the FACTOR program (Ferrando & Lorenzo-Seva, 2014). A parallel analysis based on polychoric correlations was used to identify the best internal structure (Freires et al., 2018). From the ordinal nature of the data collected, the EFA was carried out using the unweighted least squares (ULS) estimator with promin rotation (Lloret-Segura et al., 2014). The internal consistency of the resulting factors was determined by Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega (Trizano-Hermosilla & Alvarado, 2016) using the R software (version 4.0.0). Multiple regression analyses were performed to evidence aspects of incremental validity (Brown, 2014), by means of life satisfaction, personality, and reasons for using social media as part of the model.

Results

Step 1

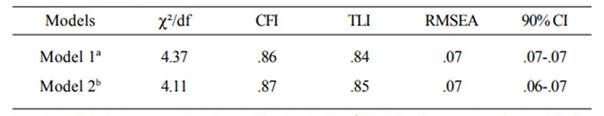

Through the CFA procedure, the original structure of the ten-factor SMM-S (Orchard et al., 2014) was tested. From the analyses performed with the Mplus software, it was observed that not all the fit indices showed fully fair values. Therefore, a new model with suggestions for modification indices was tested (F1: e15-e20; F2: e4-e35; F3: e19-e29; F4: e31-e32; F6: e9-e12; F7: e23-e25), thus presenting a slight change in the quality of the fit indices. Table 1 shows the fit indices of all models tested through the CFA.

Table 1 Fit indices of the verified models

Note: a Model without suggestions for modification indices; b Model with suggestions for modification indices

Concerning models one and two, it was observed that the internal structure of the SMM-S in the Brazilian context presented indices that could be questioned due to CFI and TLI indicators below .90.

Based on these results, a second exploratory research of the dimensional structure was conducted using the recommendations of Hauck (2019), mentioned in studies of instrument adaptation from other cultures with inadequate fits. The results are presented in the second part of the study, as detailed below.

Step 2 Results

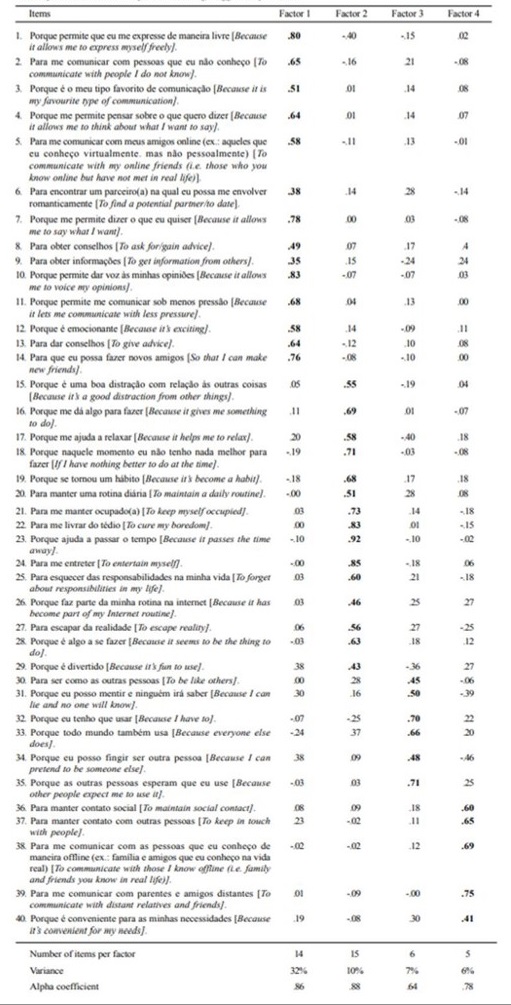

Regarding the data adjustment using the factor analysis procedure, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity indices were significant (KMO = .80; Bartlett, χ2 (325) = 4013.8; p < .001). A parallel analysis led to the decision of using a factorial structure based on the polychoric correlations matrix, which suggested the retention of four factors, as opposed to the original scale that was structured with ten dimensions. A four-factor model with the respective factorial loads of the items was identified in a new analysis using the ULS estimator with promin rotation. The scale’s factorial structure is shown in Table 2 and the adjustment indicators were: x²/df = 1.5; CFI = .99; GFI = .98; AGFI = .96; NNFI = .98; RMSEA = .04 (.01-.05).

The first dimension was formed by the combination of the factors «new connections,» «freedom of expression,» «ritual,» «recreation,» and «information exchange,» and named in the Brazilian version as Freedom in Social Networks (Liberdade em Redes Sociais - LRS). The factor was based on 14 items and explained 32% of the data variance. In general, it assessed aspects related to the possibility of expressing oneself freely through online social networks, using them as a source of information, leisure, and a different way of making new contacts. Regarding the dimension’s precision, the factor obtained Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega coefficients of .86.

The second dimension brought together the factors «procrastination» and «escapism,» which in turn is composed of the items «ritual,» «freedom of expression,» and «conformity», and was named Routine in Social Networks (Rotina em Redes Sociais - RRS). The final version of the factor had 15 items and explained 10% of the data variance. The factor evaluated aspects related to the use of online social networks as part of a daily routine, including entertainment, relaxation, and use of idle time. As for consistency, Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega coefficients were .88 and .89, respectively.

The third dimension, labeled as Identity in Social Networks (Identidade em Redes Sociais - IRS), added items from the «conformity» and «experimentation» factors of the original model. Consisting of six items, it explained 7% of the data variance. The dimension assessed issues related to the users’ identity when entering the online environment through social networks, such as their adaptation and experimentation in different ways of behaving in this context. Concerning precision, the factor presented a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .64 and a McDonald’s omega coefficient of .68.

The last and fourth factor was formed by the dimension «social maintenance» and only one item from «information exchange.» It kept its original name, Social Maintenance (Manutenção Social - MS), and presented five items that explained 6% of the data variance. In general, it evaluated aspects related to online social networks as a tool to keep in touch with people from interpersonal relationships that already existed. The internal consistency had a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .78 and a McDonald’s omega coefficient of .79.

Incremental Evidence of Validity

With psychometric indicators being more adequate in the four-dimension model (Freedom in Social Networks, Routine in Social Networks, Identity in Social Networks, and Social Maintenance), two groups of multiple regression analysis (stepwise method) were performed to gather incremental evidence of validity of the SMM-S. The first regression model took life satisfaction as a predictor and all four dimensions of the SMM-S as causative variables. The resulting model explained 14% of the data variance, with the dimensions Routine in Social Networks (β = -.24; p < .001) and Identity in Social Networks (β = -.18; p < .001) being the negative predictors. Thus, Social Maintenance was the only positive predictor (β = .30; p < .001) of life satisfaction. Freedom in Social Networks was not a significant predictor.

In the second part of the analysis, the predictors were all five dimensions of personality (extroversion, socialization, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience), with four dimensions of the SMM-S being the explained variables. The results of the models showed that extroversion was a negative predictor of Routine in Social Networks (β = -.22; p < .001; explained total of 5%) and Identity in Social Networks (β = -.11; p < .001; explained total of 4%), and a positive predictor of Social Maintenance (β = .17; p < .001; explained total of 6%). The conscientiousness trait was a negative predictor of Identity in Social Networks (β = -.15; p < .001; explained total of 4%). Finally, openness to experience was a negative predictor of Social Maintenance (β = -.13; p < .001; explained total of 6%). The traits of neuroticism and socialization were not predictors of any of the SMM-S variables and did not confirm theoretical incremental evidence of motivation to use the Internet.

Discussion

This article sought to examine the internal and incremental evidence of validity of the SMM-S (Orchard et al., 2014) to assess individual motivations for online social network usage among adults in the Brazilian context. The procedures were divided into two stages: Stage 1 proposed to translate, adapt, and preliminarily evidence the internal structure of the original ten-factor instrument based on a CFA. Stage 2 aimed to examine new structures for the SMM-S through an EFA and incremental aspects of the Brazilian dimensional structure with life satisfaction and personality dimensions. In addition, reliability tests such as Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega were performed (Trizano-Hermosilla & Alvarado, 2016), and good psychometric indicators were observed in the Brazilian Portuguese version of the SMM-S.

From the stage 1 analysis, it was found that not all fit indices proved to be adequate for the original ten-factor instrument, resulting in the model not being recommended for the Brazilian sample. It is important to highlight that the authors, when developing the SMM-S (Orchard et al., 2014), used insufficient factorial procedures, including the PCA, to extract the dimensions of the first version of the instrument. Considering the evidence of validity of a psychological instrument, the PCA is not currently the best procedure because searching for internal evidence of the instrument consists in analyzing the latent construct and not only the correlations of latent variables (Damásio, 2012; Fonseca et al., 2020).

In view of the difficulties to adjust the British model, stage 2 was performed to find an adequate structure using an EFA. Therefore, four factors were extracted: Freedom in Social Networks, Routine in Social Networks, Identity in Social Networks, and Social Maintenance. Considering the Uses and Gratifications Theory (Katz et al., 1974), the fourfactor model remained consistent with the proposal of the theoretical axis of the original study, which describes the motivations for choosing and using online social networks based on individual needs and goals, and influenced by contextual and psychological characteristics. The items combination suggested by the EFA also indicated 40 items in the final version but with a more simplified four-dimensional structure capable of assessing the needs and objectives of online social network usage. Said structure included the following: a) Freedom in Social Networks, which included the possibility of expressing ideas, as well as a source of leisure and interpersonal communication, consistent with studies that address the ease of expression that this kind of online services provide (Orchard et al., 2014), and the expression of opinions and affections (Lemos & Coelho, 2019). b) Routine in Social Networks, which addressed the entertainment provided in the individual’s daily life by online social networks: a topic already observed in studies that aim to understand its influence on human behavior (Cruz, 2020) and the habit of using online social networks in everyday life (Del Duca & Lima, 2019). c) Identity in Social Networks, which brought questions related to the user’s identity when entering the online environment through social networks: a topic observed in other studies that address, in this same context, the impacts that can occur on self-esteem (Retuerto & Guitiérrez, 2017) and self-concept (Mendes & Silva, 2017). d) Social Maintenance, which referred to maintaining the individual’s contacts from relationship networking: a result also observed in other studies, such as those that approached online romantic relationships (Lemos & Coelho, 2019; Rodrigues, 2019).

All factors showed suitable fit indices and internal consistency (Cohen et al., 2014; McDonald, 1999). However, it is important to mention that factor 3, Identity in Social Networks, presented internal consistency values below .70. Some possibilities can be considered regarding this issue. There is no unanimity about the right values concerning precision, but a common agreement is that .70 works as a cutoff. Although sometimes values between .60 and .70 are also satisfactory (de Souza et al., 2017). In this case, the hypothesis is that this dimension has fewer items compared to the others, thus affecting the internal consistency values (Cortina, 1993; de Souza et al., 2017), but it can be employed in research (Clark & Watson, 1995; Gouveia et al., 2014).

Regarding the incremental evidence of validity, it appears that with respect to personality, extroversion stands out as a negative predictor of Routine in Social Networks and Identity in Social Networks, and as a positive predictor of Social Maintenance. In line with this, extroversion has already been identified in other studies as an important motivator for the use of online social media (Pimentel et al., 2016). Additionally, it is related to the use of online social networks to maintain or expand interpersonal contacts (Conceição, 2016). Finally, Social Maintenance was the only positive predictor of life satisfaction. In other words, individuals who use online social networks to maintain interpersonal relationships tend to feel more satisfied with life. This result confirms the results of studies indicating that online social networks could increase perceived levels of social support, improve life satisfaction (Heo et al., 2015), and promote developing friendships and romantic relationships (Haack & Falcke, 2017).

The main limitation of this research was the difficulty in obtaining measures in Portuguese that could provide greater direct convergent and divergent evidence of the motivation construct for social media. Furthermore, the sample consisted of individuals from the southeastern states, which could not completely represent the results of the other Brazilian regions.

Conclusion

Although there is a difference in the number of dimensions compared to the original scale, it is believed that the instrument shows positive evidence of validity in the Brazilian context and will help future research addressing variables concerning the online context. It is suggested that the time spent and motivations for using online social networks are important elements to be analyzed with the help of the SMM-S in future research. The results will aid in interventions and research that aim at exploring self-knowledge on the use of such services and how much it may help or harm individuals in different settings (e.g., work, school). Thus, the SMM-S can be an essential tool for data collection and subsequent interventions in educational, clinical and social contexts.